Risk Factors for Teen Dating Violence Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youths: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To describe the diversity of SGMY as a vulnerable population in relation to TDV, including distinctions by sex assigned at birth and gender identity;

- To identify individual, relational, and structural risk factors associated with TDV within SGMY populations;

- To explore how different forms of TDV involvement (victimization, perpetration, or both) manifest across specific subgroups of SGMY, and how these patterns relate to intersecting minority statuses such as gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

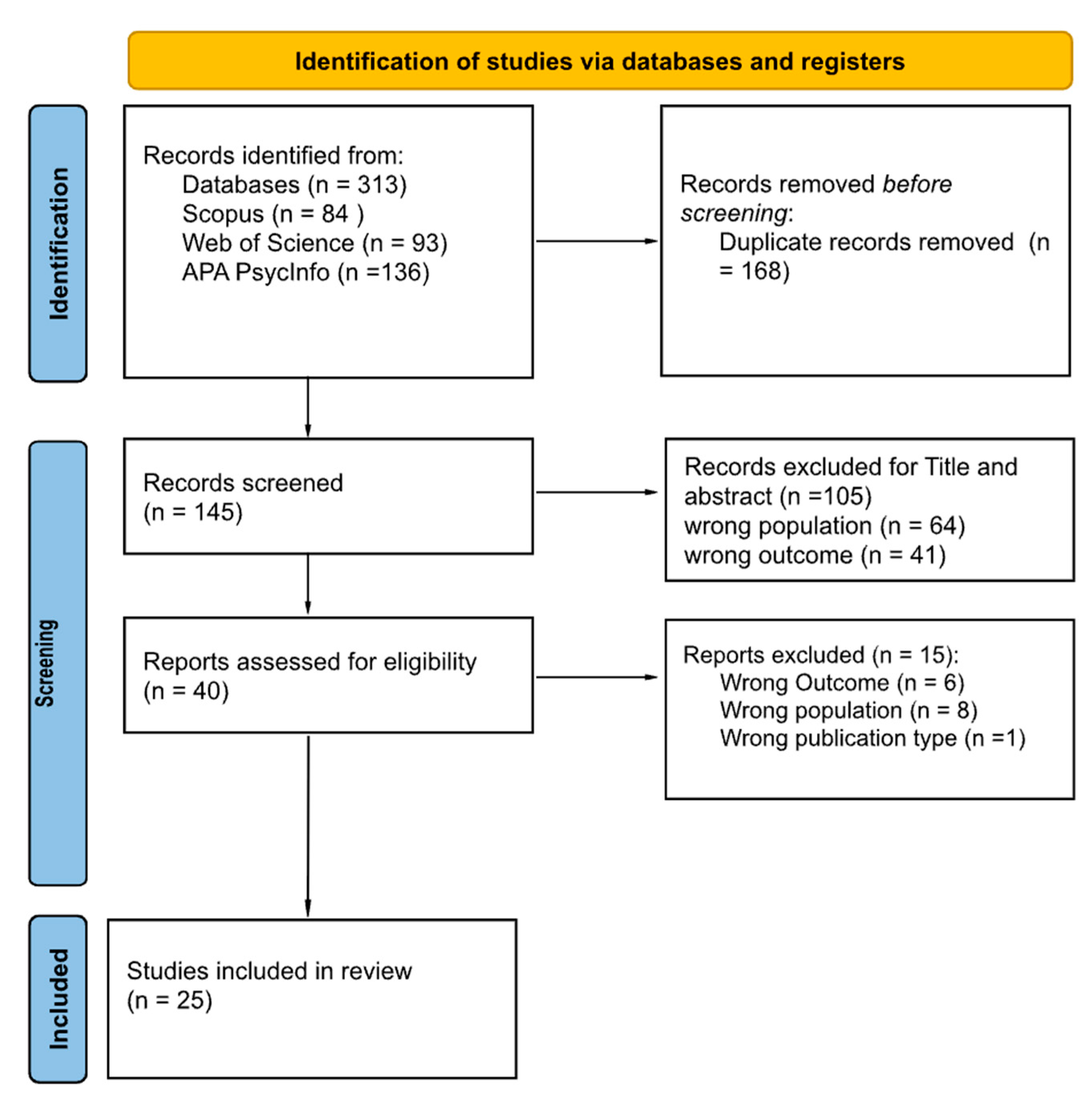

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Methodological Quality

3.3. Forms of Teen Dating Violence Investigated

3.4. Risk Factors Identified

3.4.1. Individual-Level Factors

3.4.2. Relational-Level Factors

3.4.3. Contextual and Structural-Level Factors

3.5. Subgroup Differences and Intersectional Risks

4. Discussions

4.1. High Prevalence and Heterogeneity Within SGMY Populations

4.2. Methodological Limitations and Inconsistent Operationalization

4.3. The Central Role of Minority Stress and Mental Health

4.4. Relational and Structural Risk Factors

4.5. Research Gaps and Future Directions

4.6. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Education

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wincentak, K.; Connolly, J.; Card, N. Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.C.; Clayton, H.B.; DeGue, S.; Gilford, J.W.; Vagi, K.J.; Suarez, N.A.; Zwald, M.L.; Lowry, R. Interpersonal Violence Victimization Among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020, 69, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Exner-Cortens, D.; Eckenrode, J.; Rothman, E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malherbe, I.; Delhaye, M.; Kornreich, C.; Kacenelenbogen, N. Teen dating violence and mental health: A review. Psychiatr. Danub. 2023, 35, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vagi, K.J.; O’Malley Olsen, E.; Basile, K.C.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.M. Teen Dating Violence (Physical and Sexual) Among US High School Students: Findings From the 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piolanti, A.; Waller, F.; Schmid, I.E.; Foran, H.M. Long-term adverse outcomes associated with teen dating violence: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022059654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.N.; Kanouse, D.E.; Burkhart, Q.; Abel, G.A.; Lyratzopoulos, G.; Beckett, M.K.; Schuster, M.A.; Roland, M. Sexual minorities in England have poorer health and worse health care experiences: A national survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 30, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.A.; Chapman, M.V. Comparing health and mental health needs, service use, and barriers to services among sexual minority youths and their peers. Health Soc. Work. 2011, 36, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Sylaska, K.M.; Neal, A.M. Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychol. Violence 2015, 5, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, A.M.; Devries, K.M.; Howard, L.M.; Bacchus, L.J. Associations between intimate partner violence and health among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, M.P.; Dermody, S.S.; Cheong, J.; Burton, C.M.; Friedman, M.S.; Aranda, F.; Hughes, T.L. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemieniuk, R.A.C.; Miller, P.; Woodman, K.; Ko, K.; Krentz, H.B.; Gill, M.J. Prevalence, clinical associations, and impact of intimate partner violence among HIV-infected gay and bisexual men: A population-based study. HIV Med. 2013, 14, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, F.; Stone, D.M.; Tharp, A.T. Physical dating violence victimization among sexual minority youth. Am. J. Public. Health 2014, 104, e66–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Williams, L.M. Intimate violence among underrepresented groups on a college campus. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 3210–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedner, N.; Freed, L.H.; Yang, Y.; Austin, S. Dating violence among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a community survey. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohler, B.J.; Hammack, P.L. The psychological world of the gay teenager: Social change, narrative, and “normality”. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 36, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.; Eckenrode, J.; Silverman, D. Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, E.A. Current controversies within intimate partner violence: Overlooking bidirectional violence. J. Fam. Violence 2016, 31, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, L.M.; Whitney, S.D. Risk factors for unidirectional and bidirectional intimate partner violence among young adults. Child. Abuse Negl. 2012, 36, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Sousa, C.; Cunha, O. Bidirectional violence in intimate relationships: A systematic review. Trauma. Violence Abuse 2023, 25, 1680–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blosnich, J.; Bossarte, R. Drivers of disparity: Differences in socially based risk factors of self-injurious and suicidal behaviors among sexual minority college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2012, 60, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2020, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. 2017, 5, 217–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro Jury Arnoud, T.; Linhares, I.Z.; dos Reis Rodrigues, G.; Habigzang, L.F. Dating violence victimization among sexual and gender diverse adolescents in Brazil. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13328–13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, C.; Raguet, M.; Rider, G.N.; McMorris, B.J. Predictors of adolescent intimate partner sexual violence victimization: Patterns of intersectional social positions in a statewide, school-based sample. J. Interpers. Violence 2024, 39, 2576–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dank, M.; Lachman, P.; Zweig, J.M.; Yahner, J. Dating violence experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Banyard, V.L.; Charge, L.L.; Kollar, L.M.M.; Fortson, B. Experiences and correlates of violence among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: A brief report. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 11808–11821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner-Cortens, D.; Baker, E.; Craig, W. Canadian adolescents’ experiences of dating violence: Associations with social power imbalances. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 1762–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, R.L.; Nava, N.; Rodriguez, R. Disparities in adolescent dating violence and associated internalizing and externalizing mental health symptoms by gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP15130–NP15152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazelwood, A. Looking within: An analysis of intimate partner violence victimization among sexual minority youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 8042–8064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hequembourg, A.L.; Livingston, J.A.; Wang, W. Prospective associations among relationship abuse, sexual harassment and bullying in a community sample of sexual minority and exclusively heterosexual youth. J. Adolesc. 2020, 83, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbitter, C.; Norris, A.L.; Nelson, K.M.; Orchowski, L.M. Understanding associations between exposure to violent pornography and teen dating violence among female sexual minority high school students. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP17023–NP17035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.V.; Hill, A.L.; Jackson, Z.; Gilreath, T.D.; Fields, A.; Miller, E. Adolescent relationship abuse, gender equitable attitudes, condom and contraception use self-efficacy among adolescent girls. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP22329–NP22351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, W.J.; Baams, L.; Fish, J.N.; Watson, R.J. Associations of relationship experiences, dating violence, sexual harassment, and assault with alcohol use among sexual and gender minority adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP15176–NP15204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, E.C.; Button, D.M. Interpersonal violence among heterosexual and sexual minority youth: Descriptive findings from the 2017 youth risk behavior surveillance system. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP12564–NP12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Storey, A.; Pollitt, A.M.; Baams, L. Profiles and predictors of dating violence among sexual and gender minority adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinger, A.M.; Sessarego, S.N.; Edwards, K.M.; Banyard, V.L. Bidirectional IPV among adolescent sexual minorities. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP5643–NP5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.L.; López, G.; Orchowski, L.M. Directionality of dating violence among high school youth: Rates and correlates by gender and sexual orientation. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP3954–NP3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, E.O.M.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.; Kann, L. Physical and sexual teen dating violence victimization and sexual identity among US high school students, 2015. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 3581–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, Z.J.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Davidson, L.L. Examining the intersection of bullying and physical relationship violence among New York City high school students. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, M.P.; Blais, M.; Hébert, M. Dating violence victimization disparities across sexual orientation of a population-based sample of adolescents: An adverse childhood experiences perspective. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2023, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C.M.; Norris, A.L.; Liu, G.S.; Bogen, K.W.; Pearlman, D.N.; Reidy, D.E.; Estefan, L.F.; Orchowski, L.M. Interpersonal violence victimization experiences of middle school youth: An exploration by gender and sexual/romantic attraction. J. Homosex. 2023, 70, 2901–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, T.R.; Sharp, C.; Temple, J.R. An exploratory study of teen dating violence in sexual minority youth. Partner Abuse 2015, 6, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostad, W.L.; Clayton, H.B.; Estefan, L.F.; Johns, M.M. Substance use and disparities in teen dating violence victimization by sexual identity among high school students. Prev. Sci. 2020, 21, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabina, C.; Wills, C.; Robles, G.; Cuevas, C.A. Victimization of sexual minority Latinx youth: Results from a national survey. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP23513–NP23526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, J.R.; Antebi-Gruszka, N.; Sullivan, T. Physical and sexual victimization class membership and alcohol misuse and consequences among sexual minority and heterosexual female youth. Psychol. Violence 2021, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroem, I.F.; Goodman, K.; Mitchell, K.J.; Ybarra, M.L. Risk and protective factors for adolescent relationship abuse across different sexual and gender identities. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 1521–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxton, T.; Nguyen, A.M.; Prata, N. Binge drinking and depression symptoms as risk factors for teen dating violence among sexual minority youth. J. Fam. Violence 2025, 40, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; Herrero, J.; Rodríguez-Franco, L.; Bringas-Molleda, C.; Paíno-Quesada, S.G.; Pérez, B. Validation of Dating Violence Questionnaire-R (DVQ-R). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2017, 17, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnesota Department of Education. Minnesota Student Survey Overview and Online Interactive Reports; Minnesota Department of Education: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2019. Available online: https://education.mn.gov/mde/dse/health/mss/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Foshee, V.A. Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types and injuries. Health Educ. Res. 1996, 11, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan Department of Community Health. Survey of violence against women in Michigan. In Poster presented at: American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; Michigan Department of Community Health: Lansing, MI, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, P. Tech abuse in teen relationships; Teen Research Unlimited: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.loveisrespect.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/liz-claiborne-2007-tech-relationship-abuse.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Griezel, L. Out of the School Yard and into Cyberspace: Elucidating the Nature and Psychosocial Consequences of Traditional and Cyber Bullying for Australian Secondary Students. [Unpublished honours thesis], University of Western Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, J.M.; Sayer, A.; Crockett, L.J.; Vicary, J.R. Adolescent risk factors for sexual victimization: A longitudinal analysis of rural women. J. Adolesc. Res. 2002, 17, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, J.M.; Barber, B.L.; Eccles, J.S. Sexual coercion and well-being in young adulthood: Comparisons by gender and college status. J. Interpers. Violence 1997, 12, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-González, L.; Wekerle, C.; Goldstein, A.L. Measuring adolescent dating violence: Development of ‘Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory’ short form. Adv. Ment. Health 2012, 11, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D.; Scott, K.; Reitzel-Jaffe, D.; Wekerle, C.; Grasley, C.; Straatman, A. Development and validation of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 2001, 13, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, M.; Avery-Leaf, S.; O’Leary, K.D.; Slep, A.M.S. Factor structure and convergent validity of the Conflict Tactics Scale in high school students. Psychol. Assess. 1999, 11, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A. Conflict Tactics Scales. In Encyclopedia of Domestic Violence; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, L.; Olsen, E.O.M.; McManus, T.; Harris, W.A.; Shanklin, S.L.; Flint, K.H.; Queen, B.; Lowry, R.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2016, 65. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6509a1.htm (accessed on 23 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cook-Craig, P.G.; Coker, A.L.; Clear, E.R.; Garcia, L.S.; Bush, H.M.; Brancato, C.J.; Williams, C.M.; Fisher, B.S. Challenge and opportunity in evaluating a diffusion-based active bystanding prevention program: Green Dot in high schools. Violence Against Women 2014, 20, 1179–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D.; Kann, L.; McManus, T.; Kinchen, S.A.; Sundberg, E.C.; Ross, J.G. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M.P.; Abbey, A.; Campbell, R.; Cook, S.; Norris, J.; Testa, M.; Ullman, S.; West, C.; White, J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychol. Women Q. 2007, 31, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Stein, N.D.; Woods, D.; Mumford, E. Shifting Boundaries: Final Report on an Experimental Evaluation of a Youth Dating Violence Prevention Program in New York City Middle Schools; National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby, S.; Finkelhor, D.; Ormrod, R.K.; Turner, H.A. The Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ): Administration and Scoring Manual; Crimes Against Children Research Center: Durham, NH, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A.; Douglas, E.M. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, M.L.; Chen, J.; Breiding, M.J. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, M.S.; O’Brien, K.M. Is it love or is it control? Assessing warning signs of dating violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 5446–5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Santamato, M.; Aquino, A. Individual, familial, and school risk factors affecting teen dating violence in early adolescents: A longitudinal path analysis model. Societies 2023, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woulfe, J.M.; Goodman, L.A. Identity abuse as a tactic of violence in LGBTQ communities: Initial validation of the identity abuse measure. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 2656–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F.; Farrington, D.P. Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, S8–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Tamene, M.; Orta, O.R. The intersectionality of racial and gender discrimination among teens exposed to dating violence. Ethn. Dis. 2018, 28 (Suppl. 1), 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, S.; Horton, H.; Smith, R.; Purnell, B.; Good, L.; Larkin, H. The restorative integral support (RIS) model: Community-based integration of trauma-informed approaches to advance equity and resilience for boys and men of color. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Budisavljevic, S.; Torsheim, T.; Jåstad, A.; Cosma, A.; Kelly, C.; Arnarsson, A.M. (Eds.) Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being. In Findings from the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada; International Report; Key Findings; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s), Year | Country | Racial/Ethnic Identity | Study Design | N | Age | Minorities and Non-Minorities | Minorities Only | SM Subgroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnoud et al. (2024) [26] | Brazil | White, People of color | Cross-sectional | 350 | 16–19 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual; Cis women; Non-Cis persons | |

| Cole et al. (2024) [27] | USA | Native+, Asian or Asian American, Black, African, or African American, Hispanic or Latino/a/x, White, Multiracial | Cross-sectional | 71,801 | Grade 9 and 11 | X | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Pansexual, Questioning (LGBQ+), Not described in any of these ways | |

| Dank et al. (2014) [28] | USA | Caucasian/White, African American/Black, Hispanic/Latino(a), Asian American, Native American, Mixed race | Cross-sectional | 3745 | Grade 16–19 | X | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Questioning, Queer, Other | |

| Edwards et al. (2021) [29] | USA | American Indian (AI) and Alaska Native (AN) | Cross-sectional | 400 | 12–18 | X | Bisexual, Lesbian, Other (undefined) | |

| Exner-Cortens et al. (2023) [30] | Canada | White, Black, Latin American, Indigenous, Asian, Other (including multiracial) | Cross-sectional | 3779 | Grade 9 and 10 | X | Non-binary | |

| Fix, Nava, and Rodriguez (2022) [31] | USA | Black, White, Asian American, Native North American, Pacific Islander, Multiracial, Hispanic and Latino | Cross-sectional | 88,219 | High school students | X | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Questioning their sexual orientation (LGBQ) | |

| Hazelwood (2023) [32] | USA | White, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Other | Cross-sectional | 15,187 | Grade 9–12 | X | Gay/Lesbian, Bisexual, Unsure | |

| Hequembourga, Livingston & Wang (2020) [33] | USA | White or non-White | Cohort | 800 | 13–15 | X | Bisexual, Mostly Homosexual, Gay, Lesbian, Not Sure | |

| Herbitter et al. (2022) [34] | USA | Mixed race | Cross-sectional | 1276 | 14–17 | X | Bisexual, Gay, Lesbian, Queer | |

| Hill et al. (2022) [35] | USA | Black/African American, Multiracial, White, Other, Hispanic/Latino | Cross-sectional | 246 | 13–19 | X | Sexual Minority Status | |

| Kiekens et al. (2022) [36] | USA | White, Black/African American, Native American, Asian American, Hispanic/Latino, Bi/multiracial, Other | Cross-sectional | 12,534 | 13–17 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Heterosexual, Pansexual, Asexual, Questioning, Other | |

| Levine & Button (2021) [37] | USA | White, Native American/Alaskan Native, Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islander, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Multiracial | Cross-sectional | 12,868 | Grade 9–12 | X | Sexual Minority | |

| Martin-Storey et al. (2021) [38] | USA | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 87,532 | Grade 9 and 11 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Questioning | |

| Messinger et al. (2021) [39] | USA | Race: American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian American, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, Multiracial Ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino | Cross-sectional | 398 | 13–19 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Other | |

| Norris et al. (2022) [40] | USA | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 1622 | Grade 10 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Queer, Not identified in a sexual orientation | |

| Olsen et al. (2020) [41] | USA | Race/ethnicity: White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic | Cross-sectional | 9917 | Grade 9–12 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Not sure | |

| Peters, Hatzenbuehler & Davidson (2017) [42] | USA | Race/ethnicity: White, Black/AA, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Other | Cross-sectional | 11,570 | Grade 9–12 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Not sure | |

| Petit, Blais & Hébert (2023) [43] | Canada | Not reported | Cohort | 4069 | Grade 10–12 | X | Same-gender sexual attraction, Multi-gender sexual attraction | |

| Ray et al. (2023) [44] | USA | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 2245 | Grade 6–8 | X | Attracted to Boys, Attracted to Girls, Attracted to Boys and Girls, Not Attracted to Boys or Girls, Prefer not to answer for attraction | |

| Reuter, Sharp & Temple (2015) [45] | USA | White, non-White | Cohort | 702 | Average age 17.06 years (SD = 0.77) | X | Mostly Heterosexual, Completely Homosexual, Not sure | |

| Rostad et al. (2019) [46] | USA | White, Black, Hispanic | Cross-sectional | 18,704 | Grade 9–12 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual | |

| Sabina et al. (2022) [47] | USA | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 1525 | 12–18 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Unsure/Transition | |

| Scheer et al. (2021) [48] | USA | White, Multiracial, Black or African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian American, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native | Cross-sectional | 7185 | Grade 9–12 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual | |

| Stroem et al. (2021) [49] | USA | White, African American or Black, Mixed Racial Background, Other, Hispanic | Cross-sectional | 1349 | 14–15 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Questioning, Queer, Pansexual, Asexual, Other or Unsure, Female-to-Male (FTM)/Transgender Male/Trans Man, Male-to-Female (MTF)/Transgender Female/Trans Woman, Gender-queer/Non-binary/Pangender, Other | |

| Thaxton, Nguyen & Prata (2023) [50] | USA | White, AAPI/Native Hawaiian, Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latino, Mixed | Cross-sectional | 3424 | Grade 9–12 | X | Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Questioning |

| Author(s) and Publication Year | 1. Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | 2. Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | 3. Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 4. Were Objective Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | 5. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 6. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 7. Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 8. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnoud et al. (2024) [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Cole et al. (2024) [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Dank et al. (2014) [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Edwards et al. (2021) [29] | No | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | |

| Exner-Cortens et al. (2023) [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Fix, Nava, and Rodriguez (2021) [31] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Hazelwood (2023) [32] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Herbitter et al. (2022) [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Hill et al. (2022) [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Kiekens et al. (2022) [36] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Levine & Button (2021) [37] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Martin-Storey et al. (2021) [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Messinger et al. (2021) [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Norris et al. (2022) [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Not applicable | Unclear | Yes |

| Olsen et al. (2020) [41] | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Peters Hatzenbuehler & Davidson (2017) [42] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Not applicable | Unclear | Yes |

| Ray et al. (2023) [44] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Rostad et al. (2020) [46] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Not applicable | No | Yes |

| Sabina et al. (2022) [47] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Scheer et al. (2021) [48] | No | Yes | No | Unclear | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Stroem et al. (2021) [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Not applicable | Yes | Yes |

| Thaxton Nguyen & Prata (2023) [50] | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Author(s), Year | 1. Were the Two Groups Similar and Recruited from the Same Population? | 2. Were the Exposures Measured Similarly to Assign People to Both Exposed and Unexposed Groups? | 3. Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 4. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 5. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 6. Were the Groups/Participants Free of the Outcome at the Start of the Study (or at the Moment of Exposure)? | 7. Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 8. Was the Follow-up Time Reported and Long Enough for Outcomes to Occur? | 9. Was Follow-up Complete, and if not, Were the Reasons for Loss of Follow-up Described and Explored? | 10. Were Strategies to Address Incomplete Follow-up Utilized? | 11. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hequembourg, Livingston & Wang (2020) [33] | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | No | Not applicable | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Petit, Blais & Hébert (2023) [43] | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | No | Not applicable | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Reuter, Sharp & Temple (2015) [45] | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Author(s), Year | Risk Factors That Significantly Predicted the Outcome | Outcome Measures | General TDV | TDV Victimization | TDV Perpetration | Type of TDV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnoud et al. (2024) [26] | Race; Family income; Gender; Sexual orientation (bisexual); Type of school (private or public); Attitudes towards gender and violence; Ambivalent sexism beliefs; Relationship status | Dating Violence Questionnaire based on Dating Violence Questionnaire—R [51]. | X | Psychological, Physical, Sexual, Verbal, Stalking | ||

| Cole et al. (2024) [27] | Combinations of these factors: LGBQ+ students of color, transgender, genderqueer, genderfluid, unsure of their gender, assigned male at birth; LGBQ+ students assigned female at birth, enrolled in a Greater Minnesota school; Native+ or missing race LGBQ+ students, assigned female at birth, enrolled in a Twin Cities metro area school | One item extracted from the Minnesota Student survey [52]. | X | Sexual | ||

| Dank et al. (2014) [28] | State ID—Pennsylvania; Race (non-white); Gender (female); Poor grades in school; Alcohol use; Marijuana use; Serious drug use; Number of delinquent behaviors in the last year; Sexual activity (any in lifetime); Psychosocial adjustment, frequency of depressive symptoms, anger/hostility, and anxiety; Social interactions, hours per day on computer | Teen Dating Violence and Abuse (created by the authors); Physical Dating Violence, 16 items extracted from Foshee [53]; Psychological Dating Abuse, 21 items adapted from the Michigan Department of Community Health’s [54] control and fear scales and Foshee’s [53] psychological abuse scales; Cyber Dating Abuse: 16 questions from Picard [55] and Griezel [56]. Sexual Coercion: two items from Foshee’s [53] physical abuse scale, one from Zweig et al.’s [57] scale, and one additional one from Zweig et al. [58]. | X | Psychological, Physical, Sexual, Cyber | ||

| Edwards et al. (2021) [29] | Age (being older); Sex (female); Sexual minority; School mattering; Depressive symptoms; Suicidal ideation; Alcohol use | Sexual Coercion: two items from Foshee’s [53] physical abuse scale (being forced to have sex and forced to do sexual things that person did not want to), one from Zweig et al.’s [57] scale measuring unwanted sexual intercourse (having sexual intercourse when person did not want to), and one additional one from Zweig et al. [58]. | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Exner-Cortens et al. (2023) [30] | Bullying perpetration and victimization; Social marginalization | Three items for victimization, three items for perpetration, adapted from several existing ADV measures. | X | X | Psychological, Physical, Cyber | |

| Fix, Nava, and Rodriguez (2022) [31] | Externalizing symptoms—fighting, weapon carrying, risky sexual behaviors; Race/ethnicity; Internalizing symptoms—sad or hopeless, suicide ideation/attempt; These combinations: Internalizing symptoms—sad or hopeless, suicide ideation/attempt, being LGBQ; Internalizing symptoms—sad or hopeless, suicide ideation/attempt, being female | One item for Physical dating violence, and one item for Sexual dating violence (created by the authors). | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Hazelwood (2023) [32] | LGB+; Male; Age; Black or African American; Other race/ethnicity; Ever got into a physical fight; Had sexual intercourse with four or more persons; Ever used illicit substance; Currently binge drinking; Had symptoms of depression; Past year suicidal ideation; Ever been bullied; Bisexual; Not sure minorities; Not sure minorities; Minorities—male; Minorities—Black or African American; Minorities—ever got into a physical fight; Minorities—had sexual intercourse with four or more persons; Minorities—ever used illicit substance; Minorities—currently binge drinking; Minorities—had symptoms of depression; Minorities—past year suicidal ideation; Minorities—ever been bullied | One item for Physical dating violence, and one item for Sexual dating violence—binary measures (created by the authors). | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Hequembourga, Livingston & Wang (2020) [33] | Sexual Minorities—adolescent relationship abuse, bullying victimization, sexual harassment | The Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory—Short Form—CADRI [59,60]. | X | Sexual | ||

| Herbitter et al. (2022) [34] | Sexual minority girls | The Conflicts in Adolescent Dating Relationships—CADRI [60]. | X | X | Physical, Sexual | |

| Hill et al. (2022) [35] | Parent with high school education or less, low gender-equitable attitudes, low contraception self-efficacy, low condom self-efficacy; Parent with high school education or less, high gender-equitable attitudes, high contraception self-efficacy, high condom self-efficacy, belonging to this group associated with grade; Parent with high school education or less, low gender-equitable attitudes, low contraception self-efficacy, low condom self-efficacy, 8th grade; Parent with high school education or less, low gender-equitable attitudes, low contraception self-efficacy, low condom self-efficacy, 9th grade; Parent with high school education or less, low gender-equitable attitudes, low contraception self-efficacy, low condom self-efficacy, 10th grade; Parent with high school education or less, low gender-equitable attitudes, low contraception self-efficacy, low condom self-efficacy, 11th grade; Parent with high school education or less, low gender-equitable attitudes, low contraception self-efficacy, low condom self-efficacy, 12th grade; Parent with high school education or less, high gender-equitable attitude, high contraception self-efficacy, high condom self-efficacy, belonging to the group associated with grade 8; Parent with high school education or less, high gender-equitable attitude, high contraception self-efficacy, high condom self-efficacy, belonging to the group associated with grade 9; Parent with high school education or less, high gender-equitable attitude, high contraception self-efficacy, high condom self-efficacy, belonging to the group associated with grade 10; Parent with high school education or less, high gender-equitable attitude, high contraception self-efficacy, high condom self-efficacy, belonging to the group associated with grade 11; Parent with high school education or less, high gender-equitable attitude, high contraception self-efficacy, high condom self-efficacy, belonging to the group associated with grade 12 | Modified version of the revised conflict tactics scale by Cascardi et al. [61,62]. | X | Psychological, Physical, Sexual | ||

| Kiekens et al. (2022) [36] | Sexual identity: bisexual; Gender identity: cisgender girls; Gender identity: transgender boys; Gender identity: non binary/assigned male at birth; Few dating experiences and low dating violence, assault and harassment, drink frequency; Few dating experiences and low dating violence, assault and harassment, binge drinking; Intermediate exposure to harassment and assault, drink frequency; Intermediate exposure to harassment and assault, binge drinking; High exposure to dating violence, drink frequency; Gender identity: cisgender girl, drink frequency, binge drinking; Gender identity: transgender boys, drink frequency, binge drinking; Gender identity: transgender girl, drink frequency; Gender identity: non-binary/assigned male at birth, drink frequency, binge drinking | One item for Physical dating violence, and one item for Sexual dating violence (created by the authors; based on [63]). | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Levine & Button (2021) [37] | Sex (male or female); Sexuality (sexual minority) | Eleven items for victimization created by the authors of the survey from where the authors extracted the data. | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Martin-Storey et al. (2021) [38] | Sexual orientation: gay or lesbian; Sexual orientation: bisexual; Sexual orientation: questioning; Sexual orientation: transgender; Sexual orientation: gender non-conformity; Peer victimization; Bullying based on gender; Bullying based on gender expression; Psychological parental abuse; Physical parental abuse; Witnessing domestic abuse; Sexual abuse by family member | Three items for victimization (one per each type of assessed violence); three items for perpetration (one per each type of assessed violence) created by the authors. | X | X | Verbal, Physical, Sexual | |

| Messinger et al. (2021) [39] | Sexual minorities | Five dichotomous (yes/no) questions for victimization and five dichotomous (yes/no) questions drawn from a larger 28-item measure [64]. | X | X | Psychological, Physical | |

| Norris et al. (2022) [40] | Sexual minorities; Gender (girls) | Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory—CADRI [60]. | X | X | Physical, Sexual | |

| Olsen et al. (2020) [41] | Sexual identity: not sure, male; Sexual identity: LGBQ, male; Sexual identity: LGBQ, female | One item for Physical dating violence, and one item for Sexual dating violence (created by the authors. Responses were recorded as continuous frequency variables and used to create a four-category composite measure (physical only, sexual only, both, none), as well as a dichotomous variable (any vs. no TDV). | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Peters, Hatzenbuehler & Davidson (2017) [42] | Male; Black/AA; Hispanic/Latino; Other race; Sexual identity: gay or lesbian; Sexual identity: bisexual; Sexual identity: unsure; 12th grade; Other grade or ungraduated; ≤12 years old; ≥18 years old; Bullied at school; EBullied | One item extracted from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) [65]. | X | Physical | ||

| Petit, Blais & Hébert (2023) [43] | Multigender sexual attraction combined with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), psychological distress, low self-esteem, substance use, number of sexual partners, revictimization risk factors, acceptance of TDV, TDV victimization in previous relationships, TDV perpetration in current relationship, peer victimization, sexual harassment, affiliation with friends that are victims of TDV, parental support, lifetime multi-gender sexual partners | Physical TDV: adapted version of the short form of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory—CADRI [60]. Sexual TDV: Nine items extracted from the Sexual Experiences Survey—SES [66]. | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Ray et al. (2023) [44] | Attraction to both boys and girls; Boys reporting any attraction to boys | TDV: Seven items adapted from Shifting Boundaries [67]; Sexual Harassment Victimization: Four-item modified version of the Shifting Boundaries Sexual Harassment Scale [67]. | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Reuter, Sharp & Temple (2015) [45] | Sexual minority: Hostility; Alcohol use; Exposure to father-to-mother violence (victimization only) | Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory—CADRI [60]. | X | X | Psychological, Physical, Sexual | |

| Rostad et al. (2019) [46] | Female; Sexual identity, male; Sexual identity, female; Gay; Bisexual; Bisexual, female | Two items extracted from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) [65]. | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Sabina et al. (2022) [47] | Sexual Minority (Latin teens); Depression; Anxiety; Hostility; Social support total; Significant other; Family; Friends | TDV victimization: modified version of the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire—JVQ [68]; conflict tactics scale-2 short form that was modeled after the CTS2, using only two items from each of the subscales, one focusing on severe behavior, the other on less severe behavior [69]. | X | Psychological, Physical, Sexual, Stalking | ||

| Scheer et al. (2021) [48] | Gay or lesbian—lifetime rape; Bisexual—lifetime rape; Bisexual—past-year sexual victimization; Bisexual—past-year sexual victimization in dating relationships; Bisexual—past-year physical victimization in dating relationships; Bisexual—any victimization; Gay or lesbian—past-year physical victimization in dating relationships; Gay or lesbian—any victimization | Two items extracted from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) [65]. | X | Physical, Sexual | ||

| Stroem et al. (2021) [49] | Female sex at birth—gender minority; female sex at birth—cisgender sexual minority; African American or black—gender minority; Parent income lower than the average—cisgender sexual minority; Do not know the mother’s education—cisgender sexual minority; Completed or attended graduated school—cisgender sexual minority; Lifetime emotional ARA—cisgender sexual minority; Lifetime emotional ARA—transgender boys and non-binary youth assigned female at birth; Lifetime emotional ARA—transgender girls and non-binary youth assigned male at birth; Lifetime physical ARA—cisgender sexual minority; Lifetime physical ARA—transgender boys and non-binary youth assigned female at birth; Lifetime physical ARA—transgender girls and non-binary youth assigned male at birth; Most recent sexual ARA—cisgender sexual minority; Most recent sexual ARA—transgender boys and non-binary youth assigned female at birth; Most recent sexual ARA—transgender girls and non-binary youth assigned male at birth; Any ARA—cisgender sexual minority; Any ARA—transgender boys and non-binary youth assigned female at birth; Any ARA—transgender girls and non-binary youth assigned male at birth | Four items for sexual, seven items for physical, four items for emotional, created by the authors of the survey from where the authors extracted the data. | X | Physical, Sexual, Emotional | ||

| Thaxton, Nguyen & Prata (2023) [50] | Sexual minority identity; History of drug use; Gender (male); Sad/hopeless; Binge drinking | Two items created by the authors of the survey from where the authors extracted the data. | X | Physical, Sexual |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulla, F.; Fiorentino, G.; La Selva, G.; Merafina, N.; Leone, S.A.; Monacis, L. Risk Factors for Teen Dating Violence Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youths: A Systematic Review. Adolescents 2025, 5, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030037

Sulla F, Fiorentino G, La Selva G, Merafina N, Leone SA, Monacis L. Risk Factors for Teen Dating Violence Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youths: A Systematic Review. Adolescents. 2025; 5(3):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulla, Francesco, Giulia Fiorentino, Giuseppe La Selva, Nunzia Merafina, Salvatore Adam Leone, and Lucia Monacis. 2025. "Risk Factors for Teen Dating Violence Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youths: A Systematic Review" Adolescents 5, no. 3: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030037

APA StyleSulla, F., Fiorentino, G., La Selva, G., Merafina, N., Leone, S. A., & Monacis, L. (2025). Risk Factors for Teen Dating Violence Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youths: A Systematic Review. Adolescents, 5(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030037