1. Introduction

The global population is aging at an unprecedented rate. The World Health Organization projects that by 2050, the proportion of individuals aged 60 and over will nearly double from 12% to 22% [

1]. As societies worldwide experience this demographic transition, the phenomenon of aging itself becomes a crucial area of sociological, psychological, and educational inquiry. This shift highlights the urgency of addressing societal attitudes toward older adults, as ageism can contribute to significant social, economic, and health disparities [

2]. Intergenerational solidarity—characterized by positive interactions, mutual support, and cooperation between different age groups—plays a fundamental role in fostering social cohesion and enhancing the overall quality of life across all ages [

3].

Ageism, defined as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination based on age, is a pervasive societal issue that has profound implications for individuals and communities [

4]. Research indicates that age-based biases can negatively impact the physical and mental health of older adults, contributing to conditions such as depression, social isolation, and even reduced life expectancy [

5]. Moreover, the harmful effects of ageism are not limited to older populations; its influence extends across the lifespan, shaping adolescents’ perceptions of aging and reinforcing negative stereotypes that persist into adulthood. Given these widespread effects, addressing ageism is essential for creating inclusive, equitable societies that value individuals across all stages of life.

To better understand and quantify ageism, researchers have developed various psychometric instruments for its measurement. One of the most widely used tools is the Fraboni Scale of Ageism (FSA), which provides a comprehensive assessment of ageist attitudes. The FSA measures multiple dimensions of ageism, including antilocution (negative speech), avoidance, and discrimination, through a 29-item self-report questionnaire. This multidimensional approach enables researchers to capture both cognitive and affective components of ageism, offering valuable insights into individuals’ implicit and explicit biases toward older adults [

6]. The FSA is particularly useful for assessing ageist attitudes among adolescents, as it allows researchers to examine early-stage perceptions that may influence future behaviors and interactions with older populations [

7].

Educational interventions designed to simulate aging have been proposed as a means to influence youth perceptions and attitudes toward older adults. Such interventions provide experiential learning opportunities that promote a practical and empathetic understanding of the physical and cognitive challenges associated with aging [

8]. However, previous studies on the effectiveness of aging simulations in altering attitudes have yielded mixed results. While some research suggests that these interventions lead to positive shifts in attitudes, others indicate minimal or temporary impact. This inconsistency underscores the need for further investigation into the specific conditions and methodologies that enhance the effectiveness of these interventions [

9,

10]. Identifying the most effective strategies for reducing ageism is critical for fostering intergenerational understanding and promoting social inclusivity in an aging world.

The aim of this pilot study was to examine the effectiveness of a brief aging simulation in altering adolescents’ perceptions of aging and older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective interventional study with a triangulation of methods investigated high school students’ attitudes towards the elderly and examined whether a brief simulated aging experience could influence these attitudes. Data was collected at two time periods—before and after a subset of students wore an aging simulation suit. The investigation (baseline testing, intervention, repeated testing, and data analyzing) were performed between September and December 2024. In total, 63 high school students aged 16 to 18 from grades 10, 11, and 12 at the Ruđer Bošković Educational System were recruited. Inclusion criteria were current enrollment in grades 10 through 12 and the willingness to participate. Exclusion criteria included refusal to participate or the inability to wear the suit due to a physical limitation.

All participants completed an online questionnaire with 3 subsets of questions: demographic information (e.g., sex, age, and grade), family structure (e.g., whether they have living grandparents or live with them), and the frequency and type of contact with grandparents (e.g., daily, weekly, or monthly). They also provided qualitative responses describing what they appreciate or enjoy about spending time with older relatives or older adults in general. To ensure confidentiality, the questionnaire was anonymized using a coded system in which each participant generated a unique alphanumeric code known only to themselves. The questionnaire was presented and completed on individual tablets provided by research. The questionnaire included 17 questions regarding participants’ attitudes toward aging and the elderly and the FSA to measure students’ baseline attitudes toward older adults. This scale evaluates multiple aspects of ageism, including stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Participants responded on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We used the version of the FSA in Serbian [

11], which was previously translated and preliminarily validated [

12] and transculturally adapted [

11].

Out of the 63 participants, 20 were randomly selected to wear the SD & C Senior Suit Alpha 3 using IBM SPSS Statistics (v.23) for randomization. This aging suit simulates a range of age-related physical and sensory impairments, including hearing loss (particularly high-frequency impairment), vision deterioration (such as reduced color discrimination and peripheral vision), and reduced range of motion in the head, shoulders, elbows, knees, and wrists. It also diminishes muscle strength and coordination, increases joint stiffness—affecting balance and mobility—and reduces fingertip sensitivity. These combined effects lead to impaired coordination, balance, and communication abilities, closely mirroring the physical challenges commonly experienced by older adults.

While wearing the suit, these participants performed everyday tasks commonly encountered by older adults over two hours (e.g., walking upstairs, picking up objects, opening doors, and handling small items). All activities took place in a controlled environment to ensure participants’ safety and were performed in the morning (between 8 am and 1 pm). Immediately after taking the suit off, these 20 participants once again completed the FAS questionnaire [

12], and 17 questions questionnaire related to participants’ attitudes regarding aging and the elderly, using the same unique alphanumeric code they had entered on the initial questionnaire. This second measurement aimed to identify any short-term changes in their attitudes toward older adults resulting from the simulation experience. Forty-three participants who were not selected did not continue the investigation, and the results of their baseline testing were not included in this paper.

To protect confidentiality, participants were instructed to include only their unique alphanumeric code on both questionnaires. No one else had access to these codes, and there was no way to link any specific student to a particular code. All data were aggregated and analyzed at the group level.

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences IBM-SPSS, version 26.0. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and were analyzed using the Chi-square test. All continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range: 25–75th percentile) for the data that are not normally distributed. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the normality of data distribution. For intragroup comparisons, before and after intervention, the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for non-parametric variables was used. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 for all comparisons.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute on Aging in Belgrade association of citizens (Approval No. 4/2024-1, 6 June 2024) prior to the commencement of this study. Participation was voluntary, and students had the right to withdraw from this study at any point without consequences. Appropriate measures were taken to protect the physical safety of students wearing aging suits, including close supervision and clear usage instructions. After completing the simulation, the participants were debriefed about this study’s objectives and the purpose of the intervention.

3. Results

A total of 20 respondents (11 female and 9 male), ranging from the 10th to the 12th grades of high school, were analyzed before and after participating in the intervention, which involved wearing an age-simulation suit (

Table 1). Ninety-five percent of respondents indicated they have at least one living grandparent, but none lived with them. The most common frequency of contact reported was once a month, which applies to 35% of the respondents.

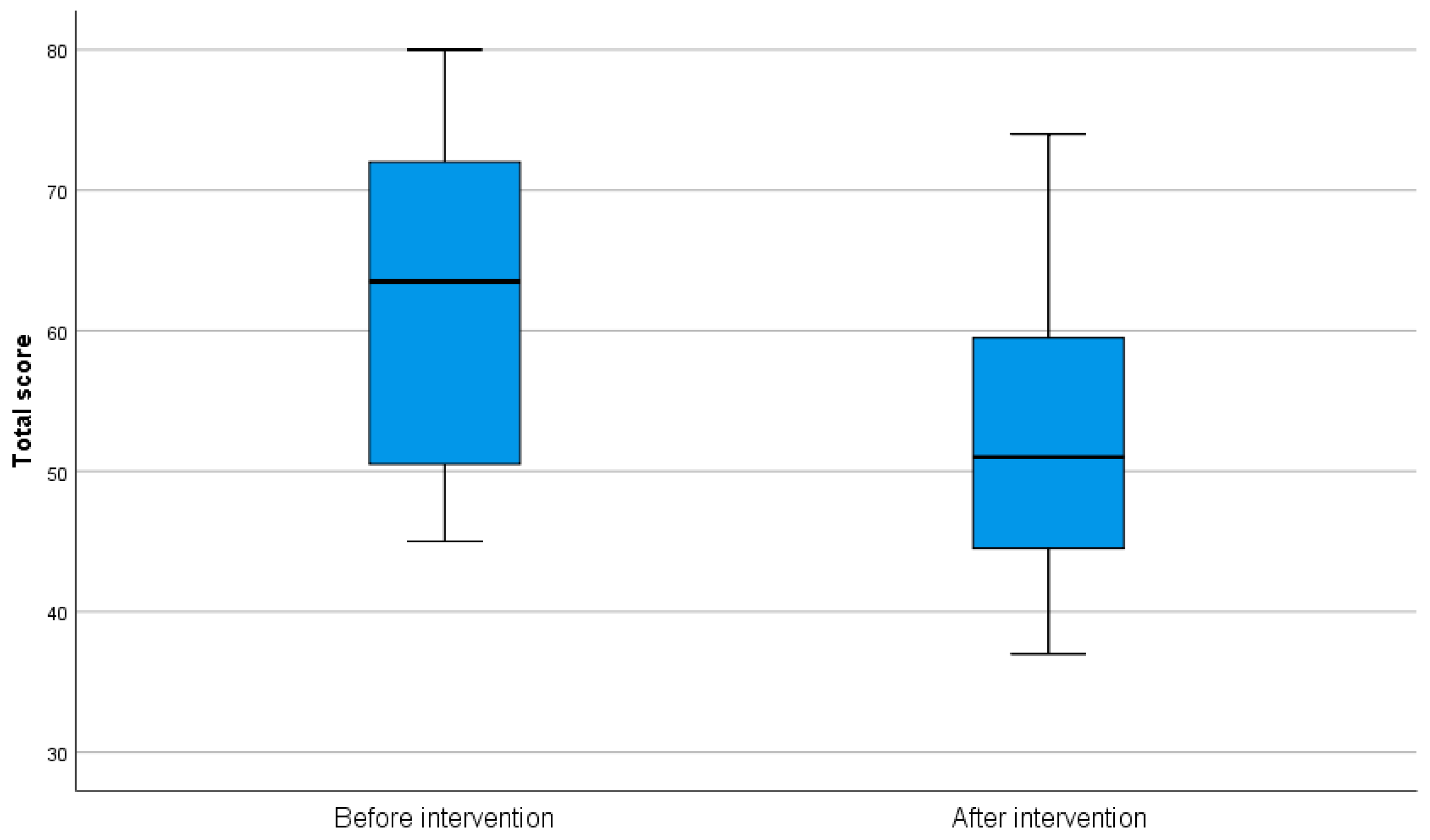

As shown in

Figure 1, there was a significant decrease in the FSA scores after the intervention, dropping from 63.50 (50.25–72.50) to 51.00 (44.25–59.75). The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test confirmed this difference to be statistically significant (

p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents the same questions posed before and after the intervention, focusing on whether respondents believed certain statements about older adults to be true. Overall, there were changes in most responses, with statistically significant differences in beliefs related to Alzheimer’s disease, the notion that older adults have more difficulty learning than younger individuals, and the perception that most older adults are alike. After the intervention, only three participants believed that older adults had Alzheimer’s disease compared to nine before. Of eight participants before intervention who believed that most elderly people were similar to each other, only one still believed so after the intervention. The participants also significantly improved their attitudes towards the difficulties of the elderly to learn new things: compared to 2/3 of respondents before intervention, less than 1/3 still believed that it was very difficult for the elderly to learn new things. As expected, wearing the simulation suit resulted in enhanced awareness of participants regarding the decrease in reaction speeds in the elderly (100% after vs. 85% before), and decrease in body height (100% after vs. 90% before). The percentage of participants who believed that an elderly person’s physical strength as well as the sensitivity of their senses decrease were initially very high (90% and 85%, respectively) and remained in the same range.

The intervention had a positive impact on changing attitudes toward the elderly and aging. A comparison of responses before and after the intervention revealed a significant difference in most answers (

Table 3). Notably, one of the most striking changes was observed in response to the question about whether elderly people are perceived as “bad.” Before the intervention, the majority of respondents believed that the elderly were bad, whereas after the intervention, 95% stated that they did not hold this opinion. Similarly, the same shift in opinion was noted regarding the statement that elderly people are unreasonable: 70% participants disagreed with this statement after intervention compared to 30% before. The improvement was marked in participants’ attitude toward activity: from 30% before intervention, the percentage who thought that elderly people were active increased to 45% after. An interesting finding was noted with regard to the statement that elderly people are worthy of respect: although the percentage of agreement was relatively high before (75%), after the intervention, it increased to 90%.

Following the intervention, participants were asked to rate their experience of wearing the aging simulation suit on a scale from 1 to 10. The average rating was 9 (ranging from 8 to 10), with the majority (17 respondents) giving a score of 8, 9, or 10. The lowest rating recorded was 5.

When asked whether wearing the suit changed their attitude toward aging and the elderly, 80% of participants reported a positive shift in perspective, stating that they now had a better opinion of the elderly. In contrast, 20% (four respondents) indicated that their attitude remained unchanged.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that a brief aging simulation experience can significantly influence adolescents’ attitudes toward older adults. The use of the FSA before and after the intervention demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in ageist attitudes, highlighting the potential effectiveness of experiential learning methods in addressing age-related stereotypes and biases. The observed decrease in FSA scores following the intervention suggests that direct exposure to simulated age-related physical impairments can foster greater empathy and understanding among youth, as observed in other studies [

13].

The significant decrease in misconceptions about Alzheimer’s disease, learning difficulties, and the perceived homogeneity of older adults underscores the ability of aging simulation to challenge common stereotypes. Prior to the intervention, a considerable proportion of respondents held the opinion of generalized aging being synonymous with cognitive decline and uniformity. However, post-intervention responses showed a marked shift towards recognizing the diversity and capabilities of older adults. This aligns with previous studies indicating that educational interventions can enhance awareness and promote more nuanced views of aging [

14].

The intervention’s impact was further reflected in the participants’ qualitative feedback. The majority of students (80%) reported a positive shift in their attitude toward aging, emphasizing that the experience provided them with a newfound appreciation for the challenges faced by older adults. This aligns with previous research suggesting that experiential learning fosters a more empathetic perspective by allowing individuals to temporarily experience physical limitations associated with aging [

15,

16]. The high engagement level, as evidenced by the average rating of 9 out of 10 for the experience, suggests that such interventions are well received by adolescents and can be an effective educational tool.

Despite these positive outcomes, it is notable that 20% of participants reported no change in their attitudes. This suggests that while aging simulations can be effective, they may not uniformly impact all individuals. Factors such as pre-existing attitudes, personal experiences with older adults, and individual susceptibility to experiential learning may influence the extent to which the participants’ attitudes are altered. Future studies could explore additional variables, such as the role of family dynamics and prior contact with elderly relatives, to understand the differential impact of such interventions.

This study’s findings contribute to the growing body of literature on intergenerational learning and anti-ageism education. Given that adolescence is a critical period for shaping lifelong attitudes, incorporating aging simulations into educational curricula could be a valuable strategy for fostering age-inclusive societies. Future research should investigate the long-term effects of such interventions to determine whether the observed attitudinal changes are sustained over time. Additionally, comparisons between different educational strategies, such as direct interaction with older adults versus simulation experiences, could provide further insights into the most effective methods for reducing ageism.

Overall, this study supports the use of aging simulation as a tool for reducing ageist attitudes among adolescents. The statistically significant improvements in FSA scores and qualitative feedback suggest that such interventions can enhance empathy and promote more positive perceptions of older adults. Therefore, many countries world-wide are trying to develop strategies of development and implementation methods which are related to aging and the older population [

17]. However, further research is needed to refine these interventions, explore their long-term effectiveness, and identify the most effective strategies for fostering intergenerational understanding and social cohesion in an aging world. All this is important because of the social support of the elderly population by the whole community, because a direct connection between social support and the quality of life of the elderly has been shown [

17]. Therefore, the aging of the population represents one of the biggest challenges facing the modern world [

18].

Limitations of this study: Because this study took place in one high school, the results may not be applicable to all adolescent populations. The short duration of the simulation experience may limit the long-term impact on attitudes; further research could examine whether changes in ageism are sustained over longer periods. Also, the terms used to describe populations such as “elderly” or “the elderly” are somewhat discriminatory and do not support the promotion of correct attitudes towards them. This limitation is inevitable when using the FAS. In addition, the simulation suit only provides negative messages about aging, introducing difficulties in everyday life that older adults confront.

However, the strength of this study is the fact that this is the first study of its kind in Serbia that, by simulating aging, tries to show the change in attitudes of adolescents towards older people.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a brief aging simulation experience can significantly reduce ageist attitudes among adolescents. The statistically significant decrease in the Fraboni Scale of Ageism scores, alongside qualitative feedback, suggests that experiential learning fosters greater empathy and a more nuanced understanding of aging. Participants exhibited notable shifts in their perceptions, particularly in misconceptions related to cognitive decline and homogeneity among older adults. While the intervention was effective for most participants, the findings also highlight that individual differences may influence their impact. Given the critical role of adolescence in shaping long-term attitudes, integrating aging simulations into educational curricula could be a valuable strategy for promoting intergenerational understanding. Future research should explore the long-term sustainability of these effects and compare different educational approaches to identify the most effective strategies for reducing ageism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.V. and N.R.; methodology, N.V. and N.R.; software, N.V.; validation, N.V. and N.R.; formal analysis, N.R.; investigation, N.V. and N.R.; resources, N.V.; data curation, N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, N.V. and N.R.; writing—review and editing, N.V. and N.R.; visualization, N.V.; supervision, N.R.; project administration, N.V.; funding acquisition, N.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute on Aging in Belgrade—association of citizens (Approval No. 4/2024-1, 6 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Ruđer Bošković Educational System, which acquired the equipment for the simulation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| FSA | Fraboni Scale of Ageism |

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights; Living arrangements of older persons (ST/ESA/SER.A/451); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Herlofson, K.; Daatland, S.O. Ageing, Intergenerational Relations, Care Systems and Quality of Life-an Introduction to the OASIS Project; NOVA; Oslo Metropolitan University-OsloMet: Oslo, Norway, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Kunkel, S.R.; Kasl, S.V. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytle, A.; Levy, S.R. Reducing ageism toward older adults and highlighting older adults as contributors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Soc. Issues 2022, 78, 1066–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraboni, M.; Saltstone, R.; Hughes, S. The Fraboni Scale of Ageism (FSA): An attempt at a more precise measure of ageism. Can. J. Aging 1990, 9, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozel Bilim, I.; Kutlu, F.Y. The psychometric properties, confirmatory factor analysis, and cut-off value for the Fraboni scale of ageism (FSA) in a sampling of healthcare workers. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leedahl, S.N.; Brasher, M.S.; LoBuono, D.L.; Wood, B.M.; Estus, E.L. Reducing ageism: Changes in students’ attitudes after participation in an intergenerational reverse mentoring program. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K. The Effect of an Aging Suit on Young and Middle-Aged Adults’ Attitudes Toward Older Adults. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardy, T.H.; Schlomann, A.; Wahl, H.W.; Schmidt, L.I. Effects of age simulation suits on psychological and physical outcomes: A systematic review. Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 953–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovac, A.; Pficer, J.K.; Stančić, I.; Vuković, A.; Marchini, L.; Kossioni, A. Translation and preliminary validation of the Serbian version of an ageism scale for dental students (ASDS-Serb). Spec. Care Dent. 2022, 42, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šesto, S.; Milosavljević, M.N.; Janković, S.; Odalović, M. Translation to Serbian and transcultural adaptation of the Fraboni scale of ageism in a population of community pharmacists. Acta Pol. Pharm.-Drug Res. 2024, 81, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallgren, J.; Stjernetun, B.B.; Gillsjö, C. Effects of an age suit simulation on nursing students’ perspectives on providing care to older persons. Innov. Aging 2023, 7 (Suppl. S1), 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacsu, J.D.; Johnson, S.; O’Connell, M.E.; Viger, M.; Muhajarine, N.; Hackett, P.; Jeffery, B.; Novik, N.; McIntosh, T. Stigma Reduction Interventions of Dementia: A Scoping Review. Can. J. Aging 2022, 41, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, D.; Taskiran, N.; Baysal, E.; Acar, E.; Cevik Akyil, R. Effect of an aged simulation suit on nursing students’ attitudes and empathy. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.E.C.; Spence, A.D.; Gormley, G.J. Stepping into the shoes of older people: A scoping review of simulating ageing experiences for healthcare professional students. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Despotović, M.; Trifković, N.; Kekuš, D.; Despotović, M.; Antić, L. Social aspects of aging and quality of life of the elderly. Pons Med Č 2018, 16, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Goodkind, D.; Kowal, P. An Aging World: 2015 International Population Reports [Internet]; Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p95-16-1.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).