Determining Predictors of Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease and Comparing It with Siblings in Benin

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Methods

Sample and Procedure

1.2. Measures

1.2.1. Outcome Measure

1.2.2. Predictor Measures

Socio-Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Clinical Characteristics

Depressive Symptoms

1.2.3. Analysis

2. Results

2.1. Patients Characteristics

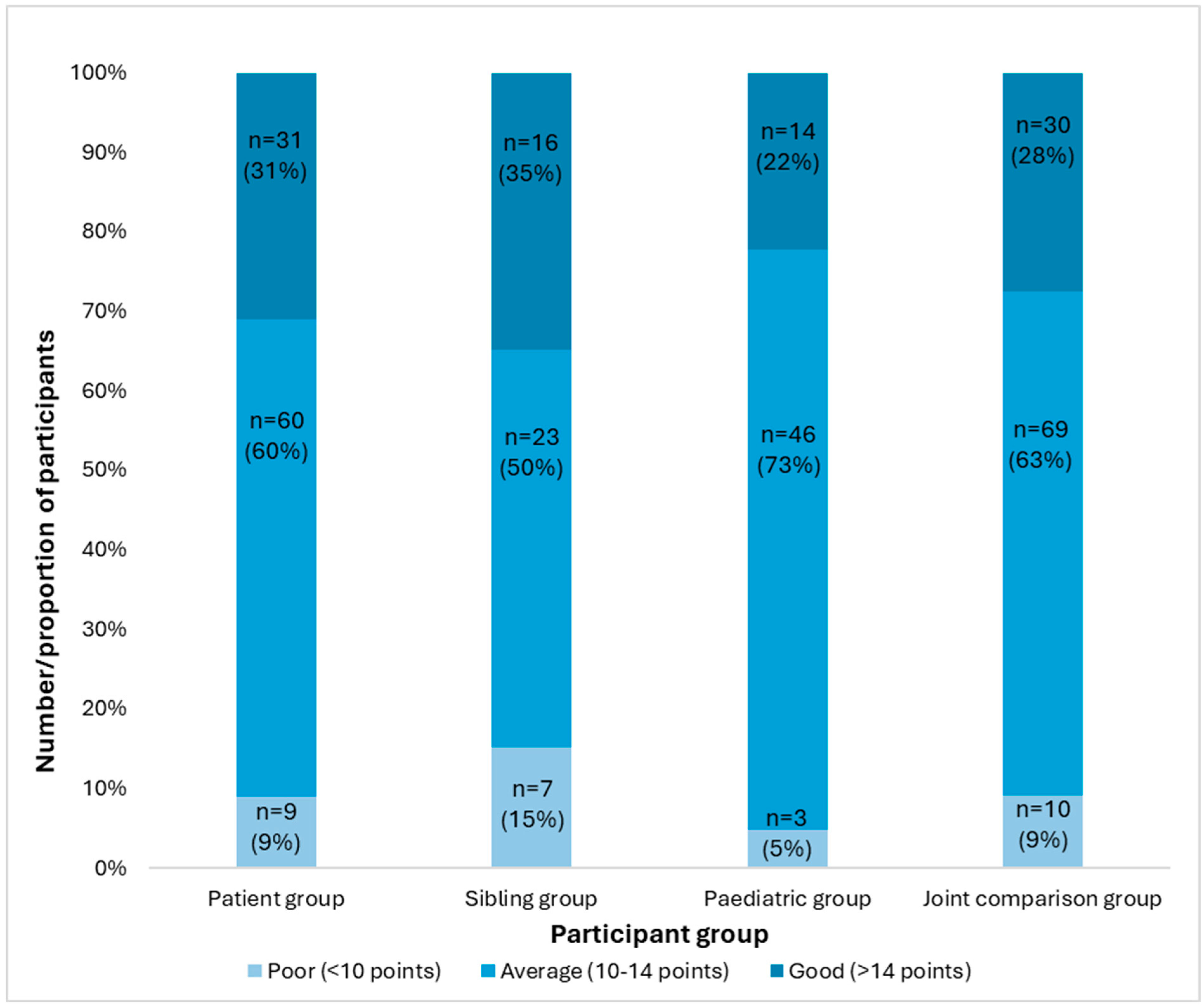

2.2. Academic Performance

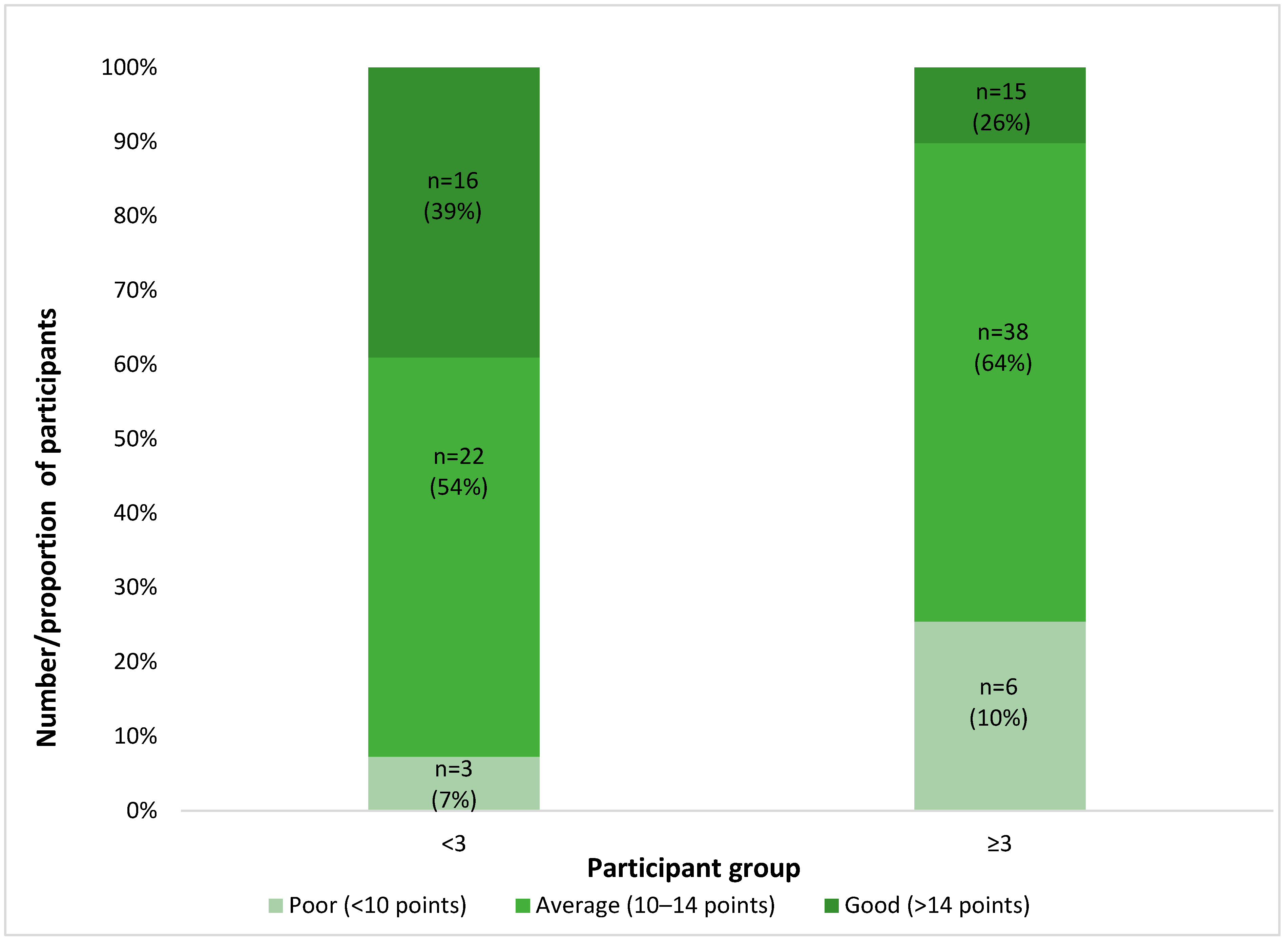

2.3. Depressive Symptoms in Patients with SCD

2.4. Determinants of Academic Performance in Patients with SCD

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schatz, J.; Brown, R.T.; Pascual, J.M.; Hsu, L.; DeBaun, M.R. Poor school and cognitive functioning with silent cer-ebral infarcts and sickle cell disease. Neurology 2001, 56, 1109–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piel, F.B.; Patil, A.P.; Howes, R.E.; Nyangiri, O.A.; Gething, P.W.; Dewi, M.; Temperley, W.H.; Williams, T.N.; Weatherall, D.J.; Hay, S.I. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: A contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 2013, 381, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballas, S.K.; Lieff, S.; Benjamin, L.J.; Dampier, C.D.; Heeney, M.M.; Hoppe, C.; Johnson, C.S.; Rogers, Z.R.; Smith-Whitley, K.; Wang, W.C.; et al. Definitions of the Phenotypic Manifestations of Sickle Cell Disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2010, 85, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnog, J.B.; Duits, A.J.; Muskiet Fa, J.; ten Cate, H.; Rojer, R.A.; Brandjes, D.P.M. Sickle cell disease; a general over-view. Neth. J. Med. 2004, 62, 364–374. [Google Scholar]

- Adegboyega, L.O. Psycho-social problems of adolescents with sickle-cell anaemia in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narad, A.; Abdullah, B. Academic Performance of Senior Secondary School Students: Influence of Parental Encouragement and School Environment. Rupkatha J. Interdiscip. Stud. Humanit. 2016, 8, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N. Self-efficacy and self-concept as predictors of college students’ academic performance. Psychol. Sch. 2005, 42, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardon, J. Facteurs Prédictifs de Retard Scolaire Chez le Patient Drépanocytaire. Médecine Humaine et Pathologie. Ph.D. Thesis, University Post-Viva Dissertation Deposit, Lyon, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heitzer, A.M.; Hamilton, L.; Stafford, C.; Gossett, J.; Ouellette, L.; Trpchevska, A.; King, A.A.; Kang, G.; Hankins, J.S. Academic Performance of Children with Sickle Cell Disease in the United States: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 786065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, A.; Hakami, K.; Abusageah, F.; Jaawna, E.; Khawaji, M.; Alhazmi, E.; Zogel, B.; Qahl, S.; Qumayri, G. The Impact of Sickle Cell Disease on Academic Performance among Affected Students. Children 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, F.; Hassan, M.; Ahmed, B. School performance of children with sickle cell disease in Basra, Iraq. Iraqi J. Hematol. 2019, 8, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasa, N.; DeBaun, M.R.; Sanger, M.; Mayo-Gamble, T.L. Student perspectives on managing sickle cell disease at school. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, L.E.; Joffe, N.E.; Irwin, M.K.; Strong, H.; Peugh, J.; Shook, L.; Kalinyak, K.A.; Mitchell, M.J. School Performance and Disease Interference in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease. Phys. Disabil. Educ. Relat. Serv. 2015, 34, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtig, A.L.; Park, K.B. Adjustment and coping in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1989, 565, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimy, M.C.; Gangbo, A.; Ahouignan, G.; Alihonou, E. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in the Republic of Benin. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 62, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimy, M.C.; Gangbo, A.; Ahouignan, G.; Adjou, R.; Deguenon, C.; Goussanou, S.; Alihonou, E. Effect of a comprehensive clinical care program on disease course in severely ill children with sickle cell anemia in a sub-Saharan African setting. Blood 2003, 102, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI and CDI 2). In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-118-62539-2. [Google Scholar]

- Allgaier, A.-K.; Frühe, B.; Pietsch, K.; Saravo, B.; Baethmann, M.; Schulte-Körne, G. Is the Children’s Depression Inventory Short version a valid screening tool in pediatric care? A comparison to its full-length version. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, B.; White, P. Why Welch’s test is Type I error robust. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2016, 12, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunya, O.S.; Oke, O.J.; Kuti, B.P.; Ajayi, I.A.; Olajuyin, O.; Omotosho-Olagoke, O.; Taiwo, A.B.; Faboya, O.A.; Ajibola, A. Factors Influencing the Academic Performance of Children with Sickle Cell Anaemia in Ekiti, South West Nigeria. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2018, 64, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenwosu, O.U.; Emodi, I.J.; Ikefuna, A.N.; Chukwu, B.F.; Osuorah, C.D. Determinants of academic performance in children with sickle cell anaemia. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.; Kirkham, F.J.; Berg, C.; Telfer, P.; de Haan, M. Executive performance on the preschool executive task assessment in children with sickle cell anemia and matched controls. Child Neuropsychol. 2019, 25, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfé, B.; Montanaro, M.; Mottura, E.; Scaltritti, M.; Manara, R.; Basso, G.; Sainati, L.; Colombatti, R. Selective difficulties in lexical retrieval and nonverbal executive functioning in children with HbSS sickle cell disease. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koury, M.J.; Ponka, P. NEW INSIGHTS INTO ERYTHROPOIESIS: The Roles of Folate, Vitamin B12, and Iron. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004, 24, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeba, A.N.; Sorgho, H.; Rouamba, N.; Zongo, I.; Rouamba, J.; Guiguemdë, R.T.; Hamer, D.H.; Mokhtar, N.; Ouedraogo, J.-B. Major reduction of malaria morbidity with combined vitamin A and zinc supplementation in young children in Burkina Faso: A randomized double blind trial. Nutr. J. 2008, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, J.; Finke, R.L.; Kellett, J.M.; Kramer, J.H. Cognitive functioning in children with sickle cell disease: A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2002, 27, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Kean, P.E. The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirin, S.R. Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 417–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornbusch, S.M.; Ritter, P.L.; Leiderman, P.H.; Roberts, D.F.; Fraleigh, M.J. The Relation of Parenting Style to Adolescent School Performance. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 1244–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, N.E.; Tyson, D.F. Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 740–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Guarda, C.C.; Yahouédéhou, S.C.M.A.; Santiago, R.P.; Neres, J.S.D.S.; Fernandes, C.F.D.L.; Aleluia, M.M.; Figueiredo, C.V.B.; Fiuza, L.M.; Carvalho, S.P.; de Oliveira, R.M.; et al. Sickle cell disease: A distinction of two most frequent genotypes (HbSS and HbSC). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, P.; Pondarré, C.; Bardel, C.; Francina, A.; Martin, C. The alpha-globin genotype does not influence sickle cell disease severity in a retrospective cross-validation study of the pediatric severity score. Eur. J. Haematol. 2012, 88, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, S.; Pirenne, F. Transfusion and sickle cell anemia in Africa. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2021, 28, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anie, K.A. Psychological complications in sickle cell disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2005, 129, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients with SCD | Sibling Comparisons | Paediatric Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 100 | 46 | 63 | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | (t, p-value) | Mean (SD) | (t, p-value) | |

| Age a | 11.1 (3.3) | 11.9 (3.20) | (−1.346, 0.180) | 12.2 (3.01) | (−2.126, 0.035) |

| Age at Inclusion b | 3.5(2.6) | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | (χ p-value) | N (%) | (χ, p-value) | |

| Sex | 0.202 (0.653) | 1.920 (0.166) | |||

| Male | 46 (46.0) | 23 (50.0) | 36 (57.1) | ||

| Female | 54(54.0) | 23 (50.0) | 27(42.9) | ||

| Education Level c | 3.249 (0.071) | 3.957 (0.047) | |||

| Primary | 53 (53.0) | 17 (37.0) | 25 (39.7) | ||

| Secondary | 47 (47.0) | 29 (63.0) | 38 (60.3) | ||

| Father’s Education | 3.248 (0.197) | 9.643 (0.022) | |||

| Level c | |||||

| Primary | 8(8.0) | 8 (17.4) | 9 (14.3) | ||

| Secondary | 37 (37.0) | 16 (34.8) | 11 (17.5) | ||

| Tertiary | 55(55.0) | 22 (47.8) | 42 (66.7) | ||

| None | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | ||

| Mother’s Education | 2.165 (0.539) | 1.188 (0.756) | |||

| Level c | |||||

| Primary | 22 (22.0) | 14 (30.4) | 13 (20.6) | ||

| Secondary | 43 (43.0) | 20 (43.5) | 26 (41.3) | ||

| Tertiary | 27 (27.0) | 8 (17.4) | 21 (33.3) | ||

| None | 8 (8.0) | 4 (8.7) | 3 (4.8) | ||

| Univariable Regression Analyses | Multivariable Regression Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | −0.309 | −0.469, −0.149 | <0.001 ** | −0.263 | −0.521, −0.005 | 0.046 * |

| Age inclusion (years) | −0.09 | −0.307, 0.129 | 0.416 | |||

| Gender (male) | ||||||

| Female | −0.127 | −1.248, 0.995 | 0.823 | |||

| Education (primary) | ||||||

| Secondary | −1.528 | −2.605, −0.004 | 0.006 * | 0.201 | −1.44, 1.845 | 0.808 |

| Father’s education (primary) | ||||||

| Secondary | 0.258 | −1.849, 2.364 | 0.809 | |||

| Tertiary | 1.755 | −0.287, 3.796 | 0.091 | |||

| No formal education a | ||||||

| Mother’s education (primary) | ||||||

| Secondary | 1.188 | −0.236, 2.612 | 0.101 | 1.058 | −0.275, 2.392 | 0.118 |

| Tertiary | 2.083 | 0.523, 3.642 | 0.009 * | 1.376 | −0.125, 2.878 | 0.072 |

| No formal education | 0.262 | −1.980, 2.504 | 0.817 | −0.109 | −2.211, 1.992 | 0.918 |

| Genotype (HbSS) | ||||||

| HbSC | 0.919 | −0.299, 2.137 | 0.138 | |||

| Hospitalisation (none) | ||||||

| 1 to 2 | 0.996 | −0.514, 2.507 | 0.194 | |||

| 3 and above | −0.648 | −2.066, 0.770 | 0.367 | |||

| Transfusion history (no) | ||||||

| (yes) | −0.011 | −1.255, 1.234 | 0.987 | |||

| Vaso-occlusive crises (none) | ||||||

| 1 to 2 | 0.675 | −0.560, 1.910 | 0.281 | |||

| 3 and above | 0.299 | −1.697, 2.296 | 0.767 | |||

| CDI score (less than 3) | ||||||

| 3 and above | −0.635 | −1.765, −0.494 | −0.267 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ikediashi, B.G.; Gomez, S.; Dedjinou, E.; Zohoun, A.; Amoussa, R.A.E.; Quenum, B.; Michel, G.; De Clercq, E.; Roser, K. Determining Predictors of Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease and Comparing It with Siblings in Benin. Adolescents 2025, 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030030

Ikediashi BG, Gomez S, Dedjinou E, Zohoun A, Amoussa RAE, Quenum B, Michel G, De Clercq E, Roser K. Determining Predictors of Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease and Comparing It with Siblings in Benin. Adolescents. 2025; 5(3):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030030

Chicago/Turabian StyleIkediashi, Bonaventure G., Selma Gomez, Edwige Dedjinou, Alban Zohoun, Roukiyath Adjile Edjide Amoussa, Bernice Quenum, Gisela Michel, Eva De Clercq, and Katharina Roser. 2025. "Determining Predictors of Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease and Comparing It with Siblings in Benin" Adolescents 5, no. 3: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030030

APA StyleIkediashi, B. G., Gomez, S., Dedjinou, E., Zohoun, A., Amoussa, R. A. E., Quenum, B., Michel, G., De Clercq, E., & Roser, K. (2025). Determining Predictors of Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease and Comparing It with Siblings in Benin. Adolescents, 5(3), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030030