1. Introduction

“In 1978, after sitting behind the mirror and seeing our team (at the Brief Family Therapy Center), work with clients advertised as “highly resistant” by the referring therapists and seeing, these clients cooperate readily with us, we decided that a little conceptual violence, was called for and thus we murdered resistance.”

(Opening Paragraph of Resistance Revisited, Steve de Shazer, 1989) [

1]

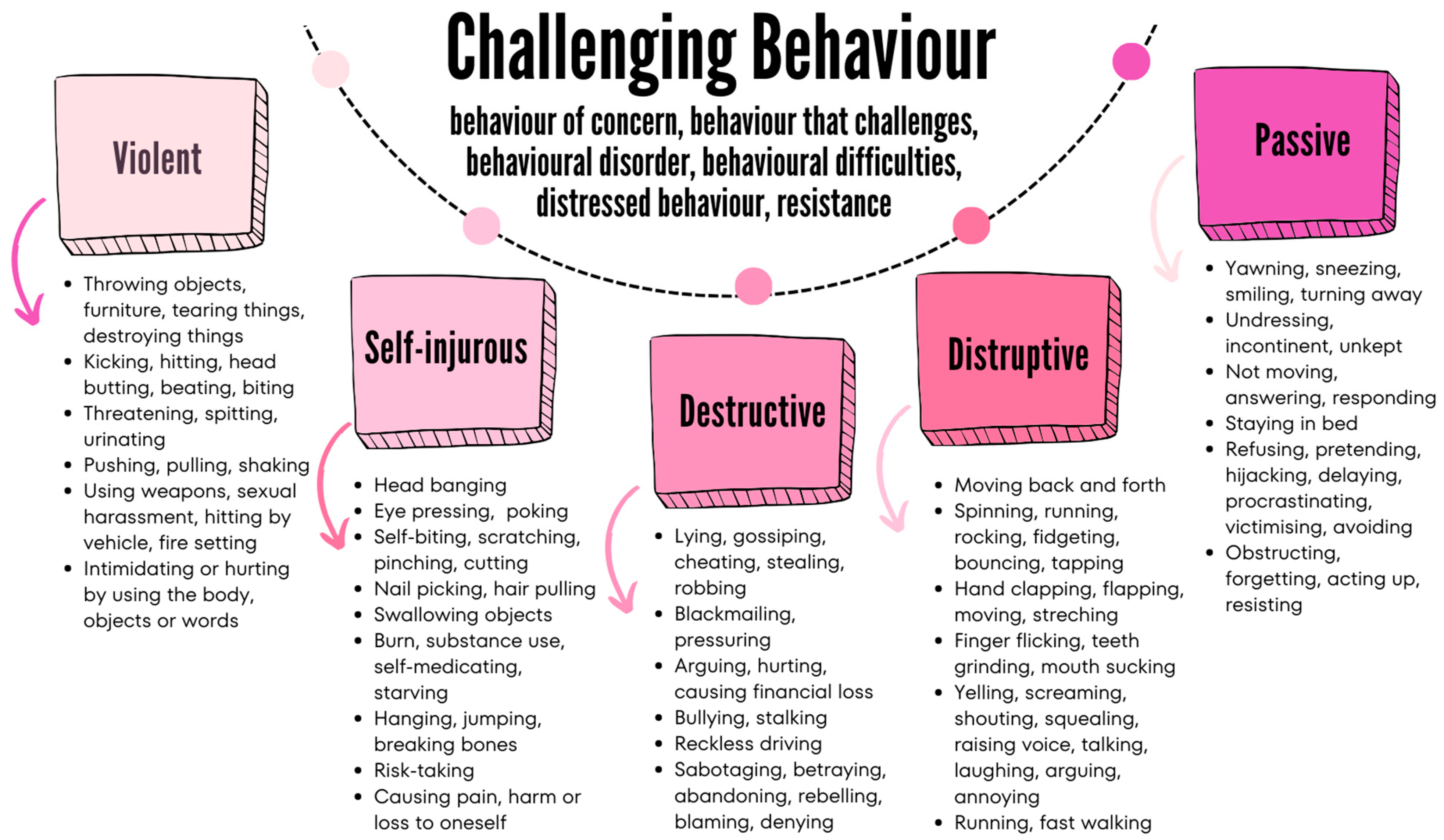

In this article, we introduce what we mean by solution focused (SF) conversation and suggest that when compared to traditional models concerning challenging behaviours, the approach offers a distinct perspective. One which does not deny that young people get angry and sometimes feel unable to control themselves but rather an approach that attempts to put such energy to some kind of use. For the purpose of this exploration, we are primarily referring to those young people who fit into the non-violent categories of most challenging behaviour models (Self-injurious, Destructive, Disruptive, Passive) rather than those young people who are habitually violent per se. The NHS (National Health Service, the publicly funded healthcare system in England, UK) explains challenging behaviour for both children and adults as behaviour that “puts them or those around at risk or leads to a poorer quality of life”.

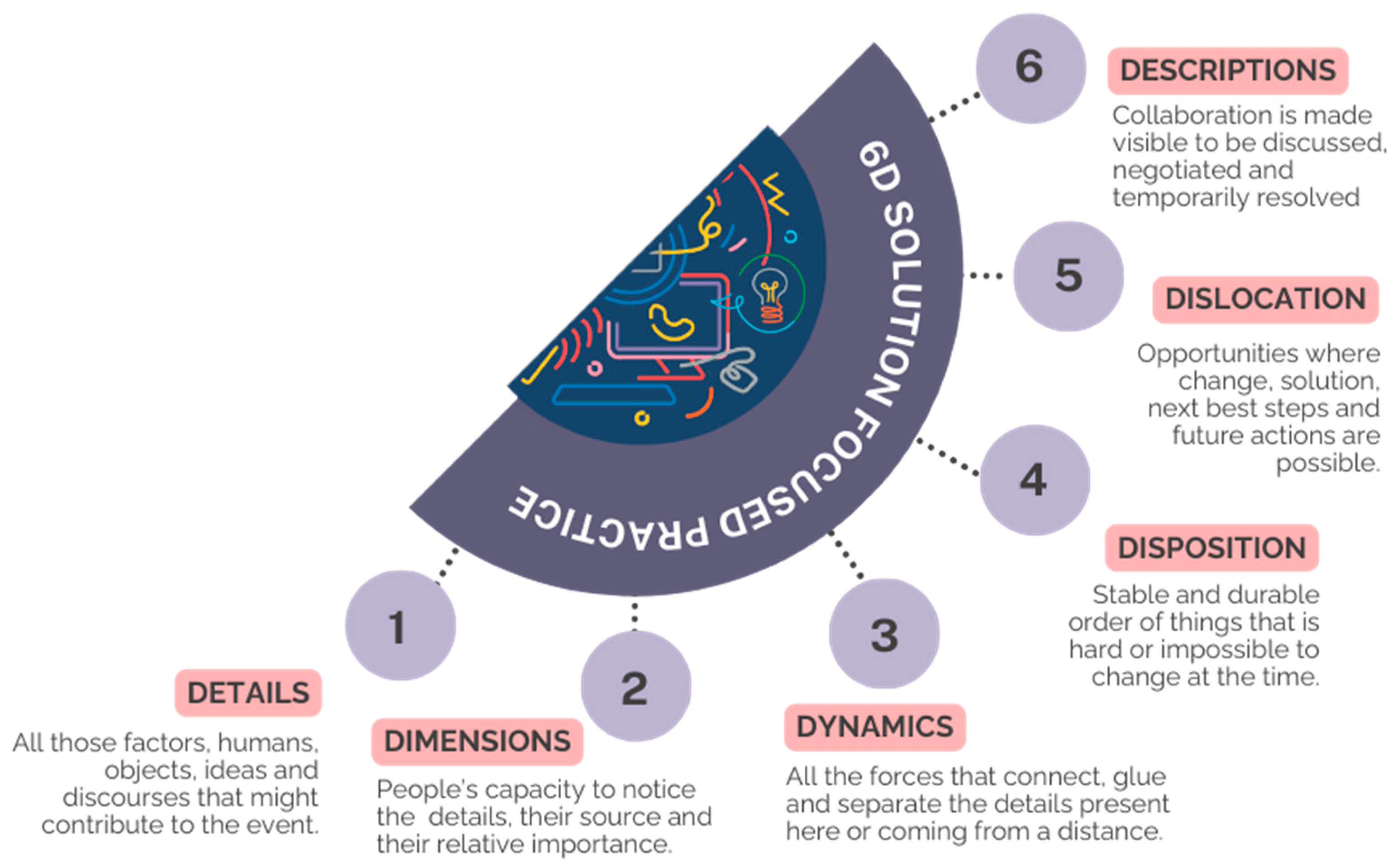

During the past 10 years, we have been involved in weekly supervision of health and social care professionals working with adolescents aged 16 to 21. A prominent theme is how these teams should work in regard to the subtle challenging behaviours shown by many of the young people. As a result, Anita applied a 6D model (details, dynamics, dimensions, dispositions, dislocations, descriptions), a palette of interventions for assessing and analysing clients’ adoption and adaption of SF conversation in their everyday interactions with the young people in their care. This article has the following three aims:

First, to explore the notion of challenging behaviour and resistance and suggest they are frequently encountered behaviours, especially in specialist adolescent services, schools, and emergency care.

Second, introduce the idea of solution focused (SF) practice, explore 6D application, and offer six practical tactics for teams working with challenging behaviour.

Third, make use of brief case studies, figures, supervision group quotes, and a few simple tweaks so that practitioners, policymakers, and researchers can join us in our rethinking of what it means to deal with resistant adolescents, their families, and care giving environments.

2. Introducing the 6D Resistive Motif and SF

It seems that challenging behaviour is a normal and healthy

dimension,

dynamic, and

disposition of growing up. This is certainly the opinion of most professionals encountering it on a daily basis. It is widely recognised that young people must constantly bump against boundaries in one form or another as a means to emerge a sense of self. In cultural terms too, society seems to go through cycles of ‘out of control kid’ headlines and a general fear-mongering regarding street life culture and its parent-hating connotations. Yet, most recognise that the majority of young people today do not represent such journalistic column inches or reflect the William Golding [

2] savages’ motif. In fact, most of the professional literature and certainly that concerned with adolescent health and wellbeing recognise, as previously suggested, that growing up requires boundaries to test. This way of acting is especially prominent in the

details and

description of current digital culture. Such a trend alerts professional groups about a generation unwilling to engage or too frightened to make comments about any relevant

dislocating scheme of things, ideas that have the capacity to affect and change. Such withdrawal or overtly frenzied keyboard activity relating to social media’s tendency to encourage self-finding, self-soothing, self-harming, and group thinking, which seems to defy all logic, is espoused and exposed by established models of challenging behaviour. These new digital certainties demonstrate how contemporary uncertainty is relative in the broad field of mental health (specifically Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and learning disability services (used in the United Kingdom for intellectual disability) and the professional teams we supervise.

In addition, but not the primary focus of our thinking here, when we start considering the expansion of neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism and ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), it is possible to see how what was once a seemingly straightforward issue is nowadays proliferating and extremely complex. Increasingly, young people and the professionals caring for them are exposed to more and more, expected to be more and more, and as a result respond more and more. As such, the range of what constitutes the resistance of challenging behaviour shows itself as anything from actual physical violence right through to refusing to get out of bed. As previously noted, it is with the latter that our SF exploration is concerned because we have discovered from our own SF practice that it is not that contemporary challenging behaviour is necessarily something to pathologise or treat, but like judo, something that tends to roll with the punch. It seems that the resistance encountered by staff teams is not the same as the pre-digital expressions. The new moment is subtle, crowd-induced, and simulating a whole array of swiping left that informs, preoccupies, and consumes the resistance capabilities of young people able to pass anonymous comments day and night about global conditions, which may arouse, but over which they are never likely to have any autonomy or influence.

“It’s like our team is still using Freud to explain why Tom won’t get out of bed,” said Sally.

The groups are in silence, looking at their feet.

“I wonder if Carl Rogers had a mobile?” laughed John to lighten the mood.

So, if the nature of resistance is changing, then as a result, so is the way professionals are encountering its dynamic subtleties.

3. Detailing Challenging Behaviour and the Notion of SF Resistance

On the whole, what professionals think of challenging behaviour has remained steady and increasingly well researched and defined. So, the idea of risk is one thing that determines immediately if a young person is willing and able to join us for an hour of SF consultation. This is partially a reason why violent, suicidal, and threatening types of behaviour are not explored here because their acute nature is another conversation, but the idea of ‘quality of life’ and the following definitely is a constant theme in staff talk: “

It can also impact their ability to join in everyday activities. Challenging behaviour can include: aggression, self-harm, destructiveness and disruptiveness” [

3,

4]. Whilst there are variations in definitions and terminology (such as behaviour that challenges; emotional, behavioural, or mental health difficulties; behaviour of concern; behavioural disorders; distressed behaviour), there is general agreement within supervision that challenging behaviour is resistive conduct, which in days gone by may have been considered personal-, character-, and/or trait-driven [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Likewise, most of the supervision groups acknowledge challenging behaviour as the term preferred to describe people with learning disability whilst the other terminologies are used for adolescents with and without mental health conditions in general. We summarised challenging behaviour in

Figure 1.

For the purpose of this article, we are assuming that the notion of resistance is understood as non-violent behaviour towards parents and familiar relations, such as teachers and other authority figures including siblings and peers. Whilst there is no agreed definition, it is generally described as a form of behaviour where adolescents abuse their power to physically or psychologically dominate, coerce, and control themselves and others [

9,

10,

11]. Coogan [

12] provides a helpful history of this and draws attention to the lack of an agreed definition, but as a point of note and something increasingly experienced online, the world appears to be angrier and more divisive than ever (thus the application of flexible 6D schema for assessing how the SF supervision impacts on the professional groups). More recently, domestic abuse [

13] and antisocial behaviour and criminal activity [

14,

15], including youth-related criminal behaviour [

16], have been researched extensively [

17] in relation to resistance. As if to highlight the enormity of the issue and its causes and subsequent treatment, Moulds and colleagues [

18] rightly interrogate whether resistance is best understood within the youth justice system as opposed to structures such as the family unit, local social services, and/or specialist CAMHS. As such and by way of summarising, the issue of challenging behaviour and in particular the notion of resistance as something non-violent but detrimental to the quality of a young person’s everyday life remains and probably always will be an academically contentious issue, which leads us towards the idea that if resistance is not going away, has not morphed, and is inevitable, then what are the ways staff teams work with and account for it?

3.1. The Disposition and Description of Resistance

“It’s also the sulking that I hate”, said John, “You know, like sometimes for days, it’s worse than holding a grudge”.

“I know”, said Jack, “I’d rather they flip out or something”.

The groups are in silence.

“It’s all the stuff they read online isn’t it”, said John, finally appearing resigned to failure.

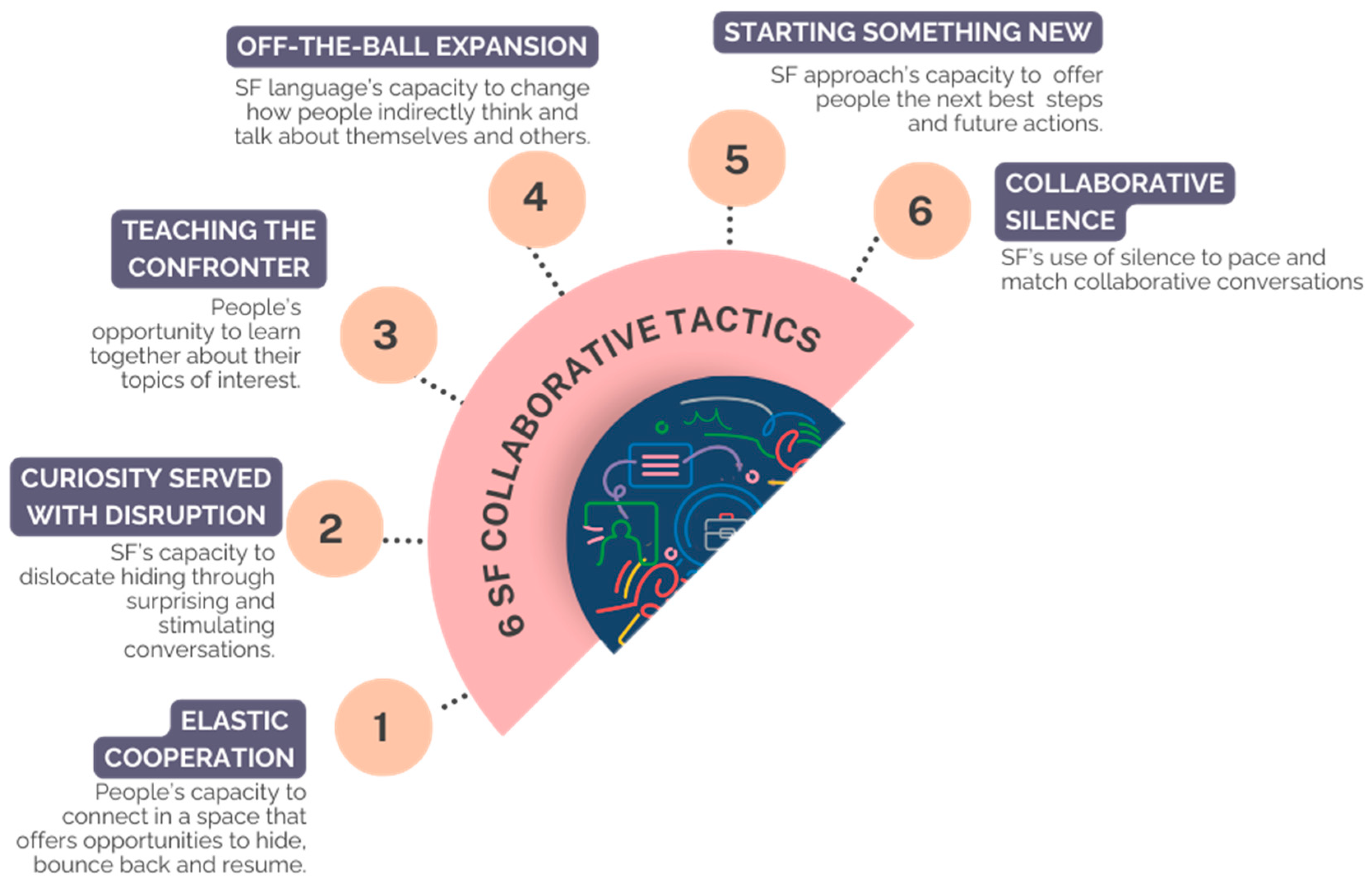

When searching for non-violent resistant behaviour in the adolescent literature, finding consensus is not only impossible, it is puzzling, as seen in

Figure 2. Resistance is excessively discussed in teenagers as a developmental characteristic, which, together with adaptation, is central to this life stage for socialisation and the forming of the autonomous self. From traditional psychological approaches through race and feminist ideas to queer theories, teenage resistance is widely explored in various contexts and against diverse theoretical backdrops. Non-violent resistance is rarely explored as a significant adolescent behaviour

per se, but it is in regards to an increasing number of socially defining issues such as the ethics of meat eating [

19], the sharing of online personal information [

20], and financial literacy [

21]. It is parents, caregivers, and professionals who are often left scratching their heads as to the vulnerable positions young people can now put themselves in and the wayward nature of the battles they fight in order to resist and ‘fit in’ [

22,

23]. And last, we forget to mention that various arrays of resistance by children and adults are also well documented in relation to healthcare services and practitioners. These include repeated missed appointments and disrupted school parent evenings through to passive–aggressive refusal and noncompliant behaviour [

24,

25].

3.2. Traditional Theories and Responses of Working with Resistance

“And then it just never stops escalating”, said John, “One thing leads to another and before you know it, he threw his shoes at the window”, emulating a throwing motion.

“And you still thought to yourself that there must be a good reason for this”? said Anita.

“Well, I don’t know that the reason was good, but I remembered your idea that I should think of elasticity and thought, ahhh, well, I’ll give him time not necessarily to calm down but catch up, so to speak”.

We want to start summing up this first half by considering that the number of theories put forward explaining challenging behaviour and resistance is substantial, so this article cannot do justice. However, we are confident in arguing that a huge part of psychology and adolescent practice is founded on structural and causative assumptions about adolescents and their behaviour, from Freud and Bandura through Piaget and Erikson to Wermer, Garmezy, and Rutter. Most essential books on child development and behaviour cover the most prominent theories like Rutter and Taylor’s

Child and adolescent psychiatry [

26], Shaffer and Kipp’s

Developmental psychology: childhood and adolescence [

27], or Shute and Slee’s

Child development theories and critical perspectives [

28]. The key thing about a traditional consideration of resistance stems from a worldview that is structural. For many clients, this is how it feels: the levels of frustration, the anger, the fear, and the low arousal states.

Whilst there are many routes to interventions, traditional theories share the aim of trying to identify the cause or reason of the behaviour as well as establishing a matching theory as we summarised in

Figure 2. Such an approach is rooted in the aspiration of a cure. A cure is only needed if there is a real or perceived normal behaviour. Like the definitions given above that regard resistance and challenging behaviour as rather harmful behaviours, most of the professionals’ training and intervention aim for the correction of such behaviours. We should not blame professionals and specialist services as such. At the end of the day, society’s attitude has not changed much. The suppression or at least the reduction in and modification of challenging behaviour, acts, and speech remain the expectation, and hence the most common response in learning disability and mental health services. This remains the case even if most contemporary practitioners would acknowledge that behaviour is just another form of communication.

Traditional theories seem to conveniently divide the world of adolescents into seemingly straightforward oppositional domains like the external and internal world, resistance versus rebellion, oppression versus empowerment, resilience versus vulnerability, or risk versus protective factors. Such traditional primarily psychological approaches are also not short of finding causes, or at least, contributing factors for such behaviours in the forms of rebellion against the parents, a sign of absent fathers, dysfunctional families, poor neighbourhood, childhood trauma, poor relationships, forms of neglect, communication problems, environmental causes, peer pressure, lack of a role model, cultural differences, and, more often than not, resistance to change. Such theorising may be comforting but in the staff supervision (as can be seen in the quotes), there is usually a resigned sense of failure, frustration, and perception that resistance cannot be used in any positive manner. So, we started to suggest that as a team, they all agree to apply some ‘elasticity’ to dealing with young people’s ‘need’ to resist in the ways they do (

Figure 1). That resistance is communication and if given the opportunity, young people might just begin to learn a new language as we suggest in the next paragraphs and

Figure 3. Meaning that, perhaps, the real resistance was to be seen in staff teams’ refusal to change, adapt, and collaborate with the changing nature of opposition. In our common approaches and interventions, there is the assumption of an opposition of something against something else or someone else.

Figure 2 breaks down the main theories of challenging behaviour on the left and the traditional and typical responses on the right to their key ingredients. In contrast, the SF-6D solution focused approach as summarised in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 adopts a more curious stance by resisting fitting young people’s behaviour into those boxes and focusing on the exception of how it might be useful, valued, or at least necessary for the moment.

3.3. Solution Focused Practice (Resistance Is Resilience)

“At times it’s like I want to scream at them to just shut up”, said Sally (Staff Nurse).

“What stops you”? asked Anita [pausing to formulate illogically].

In solution focused practice, non-violent resistance is a fundamental tool in one’s arsenal of existing, and more often than not, for survival. In solution focused practice, resistance is resilience. Based on our years of SF practice and research in mental health and learning disability with adolescents, we suggest that resistant behaviour (remembering that we have ruled out violent behaviour) and passive forms of challenging behaviour (particularly silence, sulking, and withdrawal) can be thought of as the capacity to remain resilient in the face of challenges. Instead of presupposing the logic and probably correct sensibilities that such childish behaviour is getting in the way, we have started to hypothesise that it is just a small fragment of the young person, which is not characteristic of their personality per se. In that their foolish and perhaps self-indulgent antics are ‘a stage in’ as well as an illogical yet somehow reasonable attempt to communicate, renegotiate, and strategically ‘change’. Even though we have no evidence and can offer no certainty that beyond providing a ‘can-do’ menu of things adolescents should be doing to annoy their parents, carers, and significant others, our SF rethinking is little more than taking the logic out of the challenging behaviour theory and replacing it with hope, we appreciate that this requires a lot of explaining.

In his article, ‘The Death of Resistance’, Steve De Shazer [

29] argued that clients in therapy generally have a good reason for saying and doing what they do, so it is best for the therapist to act in a manner that promotes cooperation and subsequently builds optimism. Now, that is not to acknowledge how teenagers may not have the knowledge or wherewithal to know better and also require boundaries, but it is to suggest that their worldview is probably the thing that determines the subtle resistance and annoying things they do that we professionals would consider some type of challenging behaviour. As a result, in our SF practice, we aim to collaborate in such a manner so as to allow young people the space to emerge ‘the means’ to dislocate and change their worldview and construct different and hopefully more positive behaviours not shown in

Figure 1. We need to explain more: first, the principle that on the whole, and given the chance, young people will cooperate; second, they will generally respond to confrontation with resistance so it is best if the professional adopts a curious stance; third, they are invited to join a collaborative attempt at ‘teaching the therapist and professional’; fourth, off-the-ball expanding of their SF vocabulary (not a direct result of actions but happening as an effect or accumulation of a number of events and usually not predictable in advance but seems obvious looking back) so that incrementally they can make better choices; fifth, start something new about the best of themselves; and sixth, respond to silence as a pacing tactic of collaboration as shown in

Figure 2.

3.4. The 6D Solution Focused Practice of Working with Resistance

“So your hope is you don’t have to keep punishing him, what else”? asked Anita.

“I said if you get drunk one more time and come home drunk, you are out”, said Sally. [pondering to formulate] “Huhu, how come”? asked Anita.

“Because that’s exactly what he should be doing”, said Sally [bemused by the question].

“No, how come you didn’t threaten him with more punishment”? [the difference between the best hope and perceived reality].

We now want to continue by highlighting how Anita’s 6D practice offers a model for rethinking SF collaboration for groups of professionals relating to each other and themselves as a result of the details, dimensions, dynamics, dispositions, dislocations, and description that challenging behaviour triggers. Anita’s supervision of residential and community staff teams caring for teenagers aged between 16 and 21 at times brought up some fiery debate between members. There is nothing better than the challenging behaviour of the young people to show up the dynamics and disposition of the group. These concepts being the first of an emergent model we call 6D. Descriptions help us curiously explore the many contributing factors (details) and the nature of the connections between them (dimensions) to notice what solutions might emerge from these interactions (dynamics). The 6D helps us accept the things we cannot change, or at least not right now (disposition), and where there are opportunities for the next best steps and future actions (dislocation). In other words, 6D considers all the possible humans, objects, ideas, behaviours, and discourses, such as communication and collaboration. Dimensions remind us that details have a span reflecting the structuring nature of difference and humanity to operationalise illogical and even imaginary factors into the collaboration. Such dimensions and details interacting with each other have the capacity to compose a range of dynamics between professionals and indeed, behaviour prompting us to drop or emphasise premature assumptions of what might be possible. Disposition is a constituting force that forms, shapes, and orders (amongst other things) actors’ sense of control and reach, whilst dislocation gives us means to focus on opportunities and possibilities of change. Descriptions are aesthetic assembly, logics, and in SF justification in conversations providing grounds for collaboration, negotiations, change, and co-authoring new realities.

Figure 4 provides a brief summary of the 6D model.

Regardless of definition and terminology, adolescent resistance and challenging behaviour are frequently encountered behaviours in health and social care services and in the community, including schools. Teenagers also learn quickly that challenging behaviours carry consequences and face punishments in various, primarily visible, forms. Such sanctions range from admissions to inpatient units through exclusion from school and isolation in the community to lost privileges, rejected requests, and failed prospects. Consequences can be more serious and result in physical, emotional, or financial loss. So, what options do adolescents have to face the challenges and remain resilient? We suggest that silence, smiling, and other non-violent forms of challenging behaviour can serve as a means of resilience for adolescents in many situations when looked through the lens of solution focused practice.

4. Our Solution Focused Theory in Practice

“So I thought to myself that if everyone else is trying it then why not”, said Sally.

“What else”? said Anita.

“Well, I took a deep breath and without saying it, I thought I’m going to let Tom teach the confronter and that was it. I think he thought what the hell”.

“What happened”? said Anita.

“During the whole hour when he was still in bed, I didn’t push him and he was wondering what was different”? reflected Sally.

“So, you were putting difference to work”? said Anita, “You know, the idea that starting something new might disrupt old ways of behaving”.

Throughout the years, we have supervised numerous teams who have witnessed many adolescent behaviours that could not easily fit into one of those boxes, the existing and often stand-alone theories that

Figure 4 summarises. Silence and even smiling are some of them. Additionally, even if the intervention was applied from the right side of

Figure 4, derived from the observed behaviour and theories, many of which are listed on the left side of

Figure 4, it often did not achieve the ideals of a positive, supportive, and productive behaviour change, resulting in a better quality of life for the adolescents. If it worked, we would not have a large number of adolescents reoffending and readmissions to specialist inpatient facilities. The truth is that psychologists and others working in the field prefer to hide the fact that practitioners in real-world events are often confronted with surprising, complex, and unexpected behaviours. In fact, in everyday life, whether we are in a ward or residential facility, in supported living, in a community setting, or in the classroom, we are rarely in the position to identify one or two seemingly corresponding universal and general laws of human behaviour from the left side of

Figure 4, observe long enough the traits on the right side of

Figure 4, and then consider all of them with the observed behaviour seen in

Figure 1. This is partly because general laws hardly exist when it comes to human behaviour. What is the function of silence? What is the cause of silence? What do professionals see? What does silence look like? Practitioners also have no way of knowing all the facts of the observed behaviour, including the person’s history, family, environment, financial position, and the rest, to match those to a probable theory. At best, we can propose that something may be the case, experiment with an intervention, assess, analyse, review, and move on. Do the same or do something else. Let us continue with Tom in a different situation. A nurse, psychologist, carer, social worker, or customer in a shopping centre observes Tom’s behaviour.

“…Tom suddenly stops. He looks down, up and around. The next moment, Tom becomes visibly agitated. He starts shouting. His body is rumbling, his gestures become chaotic. His behaviour disturbs others. He picks up an empty can and throws it away. His body is shaking. His voice is loud and aggressive…”

4.1. The Disposition of Doing Difference

In this case, establishing Tom’s behaviour challenges would not generate a very controversial debate. To be able to respond to Tom’s behaviour with an intervention or solution, traditional approaches follow one of two routes. The first option is to look for a rule, a theory like all those psychological ideals in

Figure 4 on the left side that promotes that behaviours can be separated into causes and effects. One such example might be Tom being distressed. Tom has learnt that aggression and loud shouting are ways to deal with frustration. We have the ‘facts’ (shouting, aggression, throwing objects, fast body movement) to correspond to the theory (learnt behaviour or conditioning) if we also know or usually in real life assume that Tom’s father behaves the same way. One or a handful of theories, a few ‘facts’, and the observation give us a case, an intervention, and an outcome. Some professionals would reject such an approach and go with the second most popular option. First, they collect as many ‘facts’ as possible about Tom’s observed behaviour. They start from the right side of

Figure 4. How loud is Tom’s shouting? How long does it last? Is it repeated? Was Tom aggressive towards himself? Others? Both? Where and when did it happen? Then, they match the ‘facts’ with a corresponding theory or come up with a new one, usually as a mixture of existing theories. Such a ‘random’ combination can be problematic if professionals are not aware of the underlying assumptions of such theories including what can and cannot be mixed. Either way, once again, we have a case, an intervention, and an outcome. Ironically, in both cases, the actual intervention might not even be different or logically connected. In both cases, Tom might be given medication. Tom might be removed from the mall. Tom is referred to a therapist.

In solution focused practice, we do not care much about the existing theories to find the facts that fit or the apparent facts to match them with a theory. We have limited tools or interventions to use on the one hand, and unique adolescents and their behaviour on the other in different time and space. We have also learnt that in real-life scenarios, we do not have all the facts, no matter how good our assessment is. Most of the time, we do not even have an assessment before we must act and do something. In solution focused practice, we do not cherry-pick a theory or two. Divorce, lack of a father figure, or growing up in a dysfunctional family does not necessarily bring anger issues for Tom. On the contrary, in a seemingly perfect family of four, Tom might still be shouting in the middle of a mall. The past does not bind an answer to the present without reservation, at least. We do not assume much about Tom’s shouting. All we need is a hypothesis, the best next step and possible solution. We consider various options. One of them might be that Tom’s shouting is loud. We might also observe the length and intensity of his shouting. We might ask about his family or financial situation. However, as opposed to traditional approaches, we do not put too much faith in either existing behaviour theories as a starting point or the observed facts.

4.2. The Dislocating Theories of Change

Whilst this paper does not have the room to dive deep into the assumptions 6D-orientated solution focused practice makes about the reality of professionals’ practice

per se, we felt it necessary in this paragraph to offer some theorists whose work and philosophy underpin its metaphysical position. Such a theoretical consideration focuses on the connectivity (rather than binary oppositional structures of language) making up adolescent behaviour and staff teams. Hence, the 6D has provided us with descriptors to rethink the idea that resistance is one thing, and staff groups another in their dynamically complex local resistances and dispositions of their own. There are infights, jealousies, and rivalries that dimensionally prevent professionals from being connectively honest. There are enforced and often unspoken narratives that reinforce institutional behaviours that preserve customary practices so that dislocations in the form of innovative ideas such as the six tactics appear too wishy-washy or ill advised. But we have found that many staff groups appreciate that their resistance reflects that of the young people in their care. One of the key differences between traditional approaches and solution focused practice is that the latter needs no universal background theory or complete observations. SF and 6D practice establish the likely case, knowing that there are many other possible answers. It remains open, flexible, and even revolutionary in its response to the adolescent and teamwork. We look for opportunities to be creative and responsive with the teams at the centre. The everyday usage of the ‘best guess’ or ‘hunch’ is not far off to summarise 6D solution focused practice and is often used as a criticism of the approach. We prefer to talk about the science and art of adolescent care and teamwork where solution focused practice and the 6D schema offer a frame for art. The truth is that when observing team collaboration like we do with adolescent behaviour, be it robust conversation or silence, we can usually construct many hypotheses about what a team requires, but only one or a few will be selected as ‘best explaining’ the observed behaviour to be further examined. This is due to the fact that like in Tom’s case, the signs of challenging behaviour in an ordinary setting (the bedroom), regardless of whether it involves materials (throwing objects), abstracts (staying silent), or discourses (shouting), can be ambiguous, illusionary, logical, or believable, and so does teams’ collaboration. In fact, in real-life scenarios, practitioners rarely experience statistical, genetic, familial, or other facts but signs (material, abstract, discursive) and the semiotic rather than more formal and logical associations between them. Hence, a growing number of contemporary theorists and practitioners argue, like Magnani [

30], Lipton [

31], Locke et al. [

32], and Shank [

33]—in line with Baudrillard’s [

34], Latour’s [

35], or Law’s [

36] philosophy—that in everyday life, we should not search for truths through universal reasoning but for significance and connections.

5. Discussion: Details Are ‘Beautiful in Their Own Right’

In practice, when adolescent behaviour is deemed challenging and problematic, experts enter the child’s world. They observe, assess, and judge. Professionals are rarely, if ever, locked away except in their rivalries. Adolescents are. Our task was to use the six SF tactics to extend the staff group’s confidence, motivation, and eventual change in their approach. We have achieved great outcomes in the science part of adolescent behaviour. We have statistics about adolescents, such as large collections of risks and protective factors, including finances, education, biological predispositions, and environmental influences such as the neighbourhood, size of open space, type of accommodation, or closeness to school. In fact, 20th-century science can be characterised by the obsession with finding every tiny and separate factor. We also have many theories. Davis and colleagues [

37] alone identified 82 theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences in their scoping review. Practitioners alike need to be able to identify the dozens of possible factors as well as theories and then re-join them so we do not forget Tom in the process. Curious conversations raise awareness of all these dimensions and dynamics of details that might play a role in their perceived confrontational interaction with Tom and other young people. Disruption is not the only tactic we used to help inspire and nudge the staff team to consider turning their approach upside-down and inside-out; there is also the opportunity we gave them to teach us, the supervisors, about all those things about adolescents’ behaviour.

Collaborative silence paces and matches staff members’ readiness to notice divisions in their work with the young people reflected in teamwork and the conversations between them. Whilst staff members often bounce back to their safe world, as adolescents do, the collaboration also starts entraining the idea of what if there was no such thing as opposition or resistance, as illustrated in

Figure 4. What if there was no such thing as resilience either? What if all we had were adolescents? If resistance is a way of existing, a way of surviving, rather than challenging behaviour, then it is also a way of thriving. As SF practitioners, we are more than aware of the grim reality that our everyday language operates via the use of binaries to make sense of the world around us by creating categories and oppositions, and hence order. There is nothing wrong with this. We just need to remember that first, it does not logically follow that the world itself exists in binary, like resistance versus resilience. We use this 6D tool here in this article and in practice because it is convenient and helps digest complex symbolism and materials. Whilst adolescents and professionals experience the power of language all the time, they might be less mindful of language’s capacity to affect. Hence, second, the significance of off-the-ball expansion and the careful choice of words and questions in staff supervision and collaboration, as illustrated in the short conversations, is so integral to our tactics, and staff tactics with working with adolescents.

When having group supervision, details are the first domain in the 6D solution focused practice to explore the difference between how things appear and how things are. Tom and other young people present complex dilemmas to the staff group. Continuing with the idea that staff groups are like adolescents’ behaviour as there is no opposition, but a continuum, and staff members are part of the intervention, staff groups are complex and beautiful in their own right. The 6D attempts to do the logical opposite of scientific approaches because of its use of the best explanation. Instead of critiquing staff, it attempts to put ‘the challenge to work’. Instead of directing, it disrupts. Instead of looking for causes and reasons, it asks questions. How do you see, Sally, what you see, when observing Tom? A behaviour to be considered challenging has to earn its right to be dynamically and dimensionally detailed. So does team collaboration. Hence, silence may not always be a deliberate protest, a result of fear or anxiety, but something else that definitely shows itself in much of the staff group supervision. We have no way of knowing this for sure.

Ssssshhhh, Silence and Putting Challenge to Work in Adolescent Practice—SF Tactics, the Use of 6D, and Averting the Typical Notion of Resistance and Resilience

To recap, 6D solution focused practice (details, dynamics, dimensions, dispositions, dislocations, descriptions) is a novel way of working with everyday experiences, including the way staff teams practice with young people, their families, and caregivers. During one session, both John and Sally remarked how the use of the collaborative silence tactic helped them digest and reconsider viewpoints without the usual oppositional stance as a result of feeling threatened. In other words, how, for those present in the group supervision, silence is to be a tool to remain resilient. This prompted us to offer an ‘invisible protest’ as an excellent place to start putting challenges to work. An invisible protest is a form of teenage existence—an art form itself that portrays many skills beyond teenage inpatient behaviour of rebelling. In a Baudrillardian [

38] sentiment, it is showcased how abstract and complex theories inform practice, because everything can be considered “simulatable and simulated” as “truth, reference, objective cause has ceased to exist”. In other words, when applying 6D methods, silence or a smile might not be a sign of vulnerability or weakness but the capacity to remain resilient. Silence and a smile are particularly effective ways for adolescents to refuse others, and expert professionals like nurses and social workers, and spokespersons of such groups, like psychiatrists or psychologists, speak and act on their behalf. In the same way, for Sally and John, silence was the ideal place to consider how many ways Tom’s behaviour can be viewed, experienced, observed, and retold in a staff group supervision session.

The group collaboration brought into the open how Tom’s shouting is the response of many ingredients, how his so-called resistance (or passive challenging behaviour) of not getting out of bed serves the same aim as his shouting (so long as the connection is made), and how both emerge from the same mix because it is not the problem, cause, or the past that necessarily connect his behaviour. How Tom’s behaviours appear, persist, change, and disappear are more dependent on how the staff team mediates details and dynamic interactions during group supervision says more about how they and Tom will act about resistance and rethink, re-evaluate, and experiment with ideas and considered best practices. At least, that is how it used to be until they started to consider how SF supervision is less about truth in favour of how Tom, if given the chance, might be encouraged to explore how he justifies his actions and those of the professionals, allowing space for new realities to emerge. New connections can form because the group now focuses on how many ways Tom’s truth can be considered as what works. This involves how he can detail what can be behaviourally witnessed and justified, measured, materialised, and perceived by imagination and senses. Tom’s silence is not a passive state any longer nor necessarily a weakness either. It becomes an active tool for him to rethink, re-evaluate, and resist the same way John and Sally once did. Tom’s shouting might not be challenging behaviour either, but a protest of engaging and responding in a professional’s preferred way. As the staff group supervision progressed, there is usually a growing appreciation that silence, smiling, and other forms of invisible protest have the power to change things. At one point, Vera suggested that silence could lead to unmet needs, misunderstandings, or misinterpretations of adolescents. That certainly can be the case, especially if we believe that our role is to provide definite answers that last. But if our aim is to remain resilient, to take one step at a time, and to experiment as the six solution focused tactics suggest, then we are not afraid of outcomes that are less than ideal, that need to be reconsidered, and that need to be adapted sooner or later.

SF and 6D practice privileges what works as the primary drive and logic. Additionally, in traditional approaches, anything beautiful, joyful, and successful, or in our case silent, is usually not remarkably interesting because interventions appear to form against a not-so-invisible backdrop of causes, factors, and theories. The starting point is what is wrong, rather than what works well, or how come you failed only one and not all your tasks. There is no need to fully understand Tom’s past either. Certainty is not needed to appreciate Tom’s contributions. We do not need to know or to feel to be able to act. We need hope. We need one hypothesis to start with. We need one solution to test. Invisible protest is not only important to practitioners but also as a tool to offer to adolescents as alternative interventions that aim to change and modify behaviours.

One way that teams could start to make use of SF tactics and the 6D model (see

Supplementary Material Figure S1) is to begin observing how each of the six concepts shows themselves in their everyday practice. By doing so, we can advance our theorising and, if relevant, apply new modes of practice for children and their families in need. By emerging these tools, we are encouraging teams to evolve their own practices to fit their needs.

6. Conclusions

We have attempted to be fairly reckless in our dealing with illogical therapies. Yet to state this is also quite disingenuous because even though our six SF tactics and the 6D model claim to be illogical, they only do so in the traditional sense. Both tools are, in fact, based upon well-established theories and abductive, informal logic. During the course of this article, we have briefly introduced some of this theory and how traditional models regard challenging behaviour. In summary, we conclude that challenging behaviour tests, teases, and befuddles teams of caring professionals more than other disorders by hiding in the logic of obviousness. Our solution focused tactics offer six fundamental tools to encourage collaboration, whilst the 6D method challenges the way we think about adolescents’ behaviour and staff teams. As we have discussed, at the end of the day, there is not much difference between them. The same way professionals are part of the young people’s solutions, adolescents’ behaviour has the capacity to affect staff teams.