Socio-Cultural Barriers Influencing Unplanned Pregnancy in Mugombwa Refugee Camp, Rwanda: Female Adolescents’ Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Positionality Statements

1.1.1. Autumn Eastman

1.1.2. Oluwatomi Olunuga

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Design and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

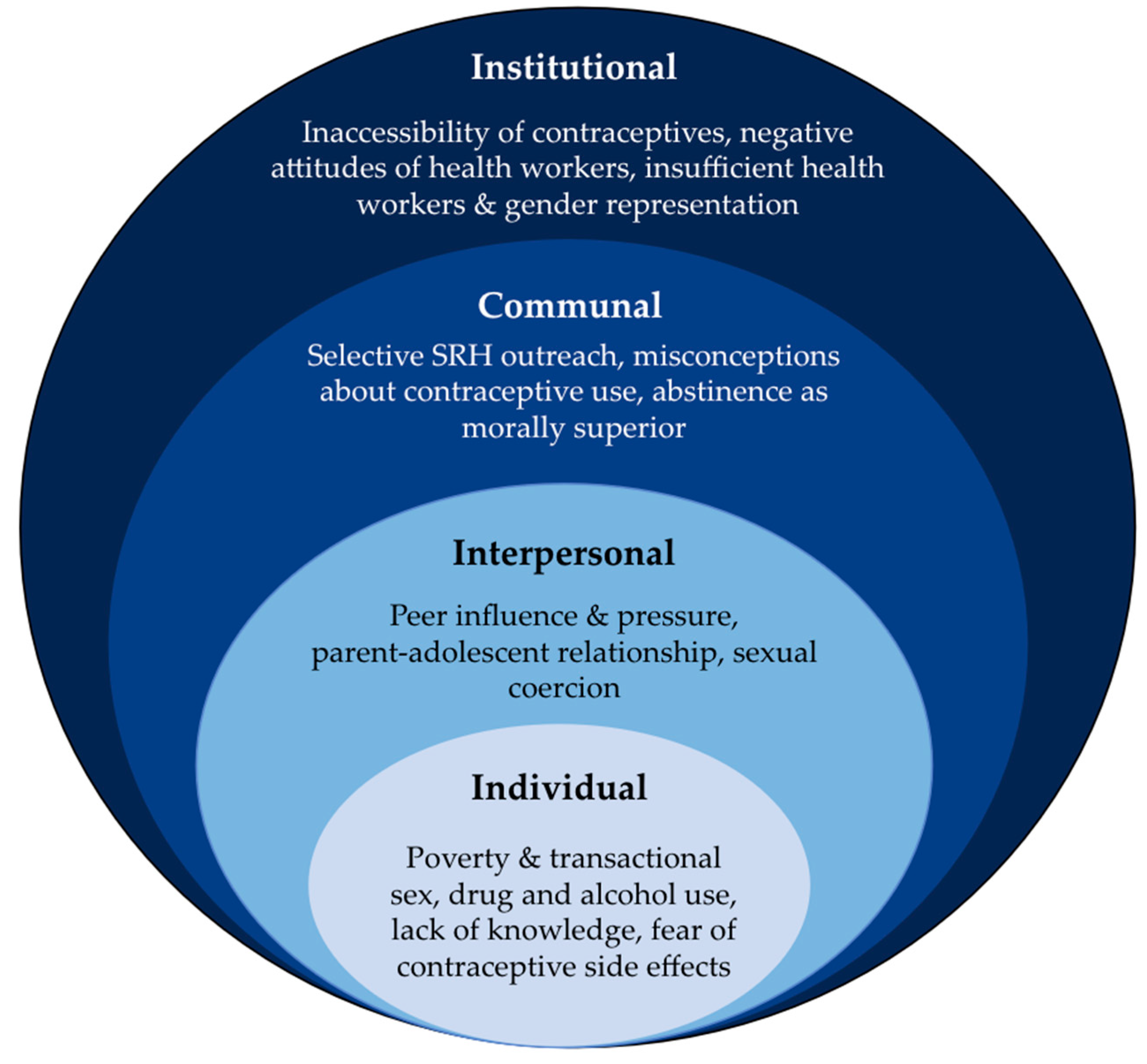

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Unplanned Pregnancy as a Leading Health Concern for Adolescents

“Something that I realized, many adolescents from our camp get pregnant at an early age.”(10–14 years old girl)

3.3. Individual-Level Factors

3.4. Poverty and Transactional Sex

“You may be at home with a problem of poverty that you feel will be solved if you go into prostitution. You feel like that bad idea will help you to have a better tomorrow.”(15–19 years old girl)

“Most of the difficulties that people of our age encounter in our community is poverty. Sometimes you can find your family being poor and not having the ability to afford all your needs and this leads to prostitution. This bad thinking and decision can ruin your future.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.5. Drug and Alcohol Use

“My point of view is that there are some girls from our age who get pregnant and are affected by HIV/AIDS due to using alcohol and drugs.”(10–14 years old girl)

“Some of the boys involve or engage in taking drugs like Marijuana and many others. After using drugs many of them think that what is next is having sex. Sometimes this may result into rape or sexual exploitation. That is my personal view.”

3.6. Lack of Knowledge about Contraception

“Sometimes adolescents don’t have enough knowledge on contraception and STIs. When they have bad habits of having sex, they may have early pregnancy or be STI positive.”(15–19 years old girl)

“Many adolescents don’t have knowledge on sexual and reproductive health. They are sometimes ashamed of asking for information about that, thinking that people will laugh at them which leads them to do what they don’t know.”(15–19 years old girl)

“Some people our age fear to use condoms on account of not having adequate knowledge about the use of them. They fear negative effects that may result from using a condom improperly.”(10–14 years old girl)

3.7. Fear of Contraceptive Side Effects

“Sometimes you feel like you want to have sex, but you immediately hear bad things about those contraceptive methods. You feel like you cannot use them. You choose to do unprotected sex and get pregnant. So, we need many people who come to us for advice.”(15–19 years old girl)

“We have been told that using IUD (intrauterine device) can bring negative effects to females. In addition to this, when a young girl engages in using contraceptive methods, this will cause ruin her life, and you may end up losing fertility. That is how I understand about that topic.”(15–19 years old girl)

“As far as I am concerned, many girls don’t prefer to use implants and injections; instead, they prefer using condoms for the sake of avoiding unintended pregnancies as well as the sexually transmitted diseases.”(10–14 years old girl)

“Some people in our community think that using IUDs can cause them to become sterile. Which is the inability to produce a child. Apart from that, the IUD can cause other serious problems. Another method that you didn’t mention is that girls should know how to count their monthly periods. This will help them to avoid unwanted pregnancies.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.8. Interpersonal-Level Factors

3.9. Peer Pressure and Influence

“Challenges people of my age or adolescents that we commonly face in our community is peer pressure. When those adolescents have bad friends, they sometimes engage in sexual relations. This contributes to the increase in the number of pregnancies in our community.”(15–19 years old girl)

“Based on what I see in our community, boys of our age are affected by peer pressure groups. In that group, some of them have girlfriends, and others don’t. Those who have girlfriends teach their colleagues some methods/techniques that they can use in order to be accepted. Some of them use alcoholic drinks as the best option of not being feared. Others advise them that if she refuses, take her by force. This will lead to impregnating that girl or getting HIV/AIDS. So boys have the problem of peer pressure.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.10. Sexual Coercion

“…There is a time when you can have sex with a boy thinking that you are using a condom while a boy has already made a hole at the head of the condom, aiming to impregnate that girl. So as girls, we have to make decisions for ourselves. About having sex, I still have enough time. It is better to do that with my own husband. About using condoms properly, it is better that a girl can be aware of checking if the condom is safe.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.11. Parent–Adolescent Relationships

“Some of our parents when you ask them about sexual and reproductive health questions, they take you as a prostitute.”(15–19 years old girl)

“For me, you can not engage yourself to ask something to your mom while she has never asked you to have conversations related to that topics. Some of us have the chance of having educated parents. When they are educated, they are aware of that and you can ask everything that you don’t know. But imagine having uneducated mom and you are willing to discuss with her about sexual activities topics. I think she cannot even allow you to discuss on that.”(15–19 years old girl)

“I would recommend the health workers to talk to our parents so that they can spare time with their children in terms of talking to them about sexual reproductive health. This will reduce unintended pregnancies, the STI, and the HIV.”(10–14 years old girl)

“My point of view, it could be better if the well-trained health workers from our community approach our parents and teach them how useful it is to talk to their kids about sexual reproductive health. This is because many adolescents at our age get pregnant, and I think this is because many parents in our community don’t spare time with their kids in teaching them about sexual reproductive health.”(10–14 years old girl)

3.12. Communal-Level Factors

3.13. Selective SRH Outreach

“Sometimes the community health workers make injustice while choosing girls in our quarters. They are used to choosing the same girls while we have so many girls in our quarter. The rest of the other girls will never have that knowledge because they train the same ones.”(15–19 years old girl)

“What can be changed in our community is that community health workers are so selective. This is where they always choose the same person on every training. I think they should take all the girls in our quarter.”(15–19 years old girl)

“My opinion is that people under fourteen years old are neglected, and based on my experience, a large number of adolescents in Mugombwa refugee camp that are impregnated are those of fourteen. This should be changed, and take from ten years then above, because there are some girls who start their monthly period at twelve.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.14. Misconceptions about Contraceptive Use

“For me, the only thing I can share is that we need a lot of information about reproductive health so that you don’t get sick or get pregnant. Because sometimes we hear false information. For example, when a virgin uses a condom, that can get inside the sex. The injection also causes disease. In general, we need enough information on these things to teach our peers.”(15–19 years old girl)

“…There are some girls or boys who decide not to use condoms during sex due to some speculations in our camp that say that once a condom is misused, it may stay in a girl’s private part.”(10–14 years old girl)

3.15. Abstinence as Morally Superior

“For me to reach out to my dream, I have to apply abstinence by avoiding unintended pregnancies.”(10–14 years old girl)

“My recommendation is that; they can reinforce adolescents to have abstinence for themselves. If not possible they can then use condom. But the first is abstinence.”(15–19 years old girl)

“The reasons why people with our age but different sex apply birth control it’s because they fail with abstinence.”(10–14 years old girl)

3.16. Institutional-Level factors

3.17. Inaccessibility of Contraceptive Services

“I really feel like we must find people here in the camp who will go and talk to the youth every week. Because young people are afraid to go to the hospital. And questioning is important to us, and it makes them less likely to engage in sexual activity.”(15–19 years old girl)

“According to me, people from our community are used to seeking condom services at our health center. It could be better if condoms are distributed in public bathrooms so that they can be available for those people who feel uncomfortable to get them at our health center.”(10–14 years old girl)

“Yes, there are so many. This is where people laugh at me, imagine at my age asking for a condom. It’s better for us to put condoms on toilets where we will get it freely.”(15–19 years old girl)

“When you are a girl and using the method of counting the days [of your menstrual cycle] will also help you. This can help you without asking for those services. You can do it for yourself.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.18. Negative Attitudes of Health Workers

“There are some service providers whom you tell your problem to, and they laugh at you. After that, you decide to never tell them all your problems.”(15–19 years old girl)

“There is a time when you ask someone a question, and they reply ‘why are you asking that question’? When you ask someone, and they tell you that, you immediately feel like you will never go back.”(15–19 years old girl)

3.19. Insufficient Health Workers and Gender Representation

“I feel maybe you are going to ask someone a question. You find that he/she has a lot of things, yet you want a quick answer. When you go and ask him, there are times when he is talking to many people.”(15–19 years old girl)

“My point of view, it would be better if our health center increases the number of nurses. I realized that a person may go to seek health services at a hospital, and it takes time to be hosted due to a big number of people who come to seek different services at the hospital. In addition, it would also be supportive if the number of health workers increases as well.”(10–14 years old girl)

“There is a time when a girl does sex, and she doesn’t get pregnant because of the advices obtained from a well-trained health worker. Mostly our health workers are used to counseling about how to avoid unintended pregnancies and the sexual transmitted diseases through using condoms.”(10–14 years old girl)

“In Mugombwa Health Center there is a lady called PELAGIE who is providing good services for adolescents. Myself and my colleague wish to have many as that lady. I think adolescents of Mugombwa refugee camp need people like her, she is flexible and we benefit more from her. So it’s better to bring more females than men. Because adolescents are more flexible when they are being advised by ladies. Of course, when he is a man, we don’t feel comfortable asking some questions. We sometimes become ashamed for asking some questions.”(15–19 years old girl)

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations and Strengths

6. Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Sexual and Reproductive Health Definition. 2022. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Life-stages/sexual-and-reproductive-health/news/news/2011/06/sexual-health-throughout-life/definition (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Adolescence: A Period Needing Special Attention—Recognizing Adolescence. 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Moore, A.M.; Awusabo-Asare, K.; Madise, N.; John-Langba, J.; Kumi-Kyereme, A. Coerced First Sex among Adolescent Girls in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prevalence and Context. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2007, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Adolescent pregnancy. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Yakubu, I.; Salisu, W.J. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grose, R.G.; Chen, J.S.; Roof, K.A.; Rachel, S.; Yount, K.M. Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes of Violence Against Women and Girls in Lower-Income Countries: A Review of Reviews. J. Sex Res. 2020, 58, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, M.; Al Haidari, T.; Chowdhury, S.; Christilaw, J.; El Kak, F.; Galimberti, D.; Gutierrez, M.; Ramirez-Negrin, A.; Senanayake, H.; Sohail, R.; et al. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of refugee and migrant women: Gynecologists’ and obstetricians’ responsibilities. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 149, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Inter-Agency Global Evaluation of Reproductive Health Services for Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons. 2004. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/41c846f44.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Williams, T.P.; Chopra, V.; Chikanya, S.R. “It isn’t that we’re prostitutes”: Child protection and sexual exploitation of adolescent girls within and beyond refugee camps in Rwanda. Child. Abus. Negl. 2018, 86, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.; Rai, M.; Kemigisha, E. A Systematic Review of Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge, Experiences and Access to Services among Refugee, Migrant and Displaced Girls and Young Women in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prickett, I.; Moya, I.; Muhorakeye, L.; Canavera, M.; Stark, L. Community-Based Child Protection Mechanisms in Refugee Camps in Rwanda: An Ethnographic Study. Child Protection in Crisis-Network for Research, Learning & Action. 2013. Available online: https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/Community-Based%20Chi335247.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Iyakaremye, I.; Mukagatare, C. Forced migration and sexual abuse: Experience of Congolese adolescent girls in Kigeme refugee camp, Rwanda. Health Psychol. Rep. 2016, 4, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukuluki, P.; Kisaakye, P.; Mwenyango, H.; Palattiyil, G. Adolescent sexual behaviour in a refugee setting in Uganda. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, A.; Adam, A.; Wirtz, A.; Pham, K.; Rubenstein, L.; Glass, N.; Beyrer, C.; Singh, S. The Prevalence of Sexual Violence among Female Refugees in Complex Humanitarian Emergencies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLoS Curr. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, L. Unable to see the future, refugee youth in Malawi speak out: Being young and out of place. Forced Migr. Rev. 2012, 40, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, K.; Millar, R. New: Refugee Children Are Five Times More Likely to Be Out of School than Others. 2016. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/refugee-children-are-five-times-more-likely-be-out-school-others (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Rwanda Humanitarian Situation Report: Burundi Refugee Response. 2016. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/rwanda/unicef-rwanda-humanitarian-situation-report-burundi-refugees-30-november-2016 (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Bol, K.N.; Negera, E.; Gedefa, A.G. Pregnancy among adolescent girls in humanitarian settings: A case in refugee camp of Gambella regional state, community-based cross-sectional study, Southwest Ethiopia. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nove, A.; Matthews, Z.; Neal, S.; Camacho, A.V. Maternal mortality in adolescents compared with women of other ages: Evidence from 144 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e155–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harakow, H.-I.; Hvidman, L.; Wejse, C.; Eiset, A.H. Pregnancy complications among refugee women: A systematic review. Acta Obs. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, M.; Sakani, O.; Spiegel, P.; Cornier, N. A study of refugee maternal mortality in 10 countries, 2008-2010. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2012, 38, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Humanitarian Action. Knowledge, attitude and practice on HIV & AIDS and SRH among refugee adolescents of 10–19 years old, living in refugee camps and Kigali city, republic of Rwanda. 2015; unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. Inter-Agency Gender Assessment of Refugee Camps in Rwanda. 2016. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/rw/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2017/06/Final-Report-IAGA.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Brahmbhatt, H.; Kågesten, A.; Emerson, M.; Decker, M.R.; Olumide, A.O.; Ojengbede, O.; Lou, C.; Sonenstein, F.L.; Blum, R.W. Delany-Moretlwe, S. Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in urban disadvantaged settings across five cities. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55 (Suppl. S6), S48–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, B.Y.A.; Baafi, D.; Dwumfour-Asare, B.; Adam, A.R. Factors associated with adolescent pregnancy in the Sunyani municipality of Ghana. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 10, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Rwanda | Global Focus. Available online: https://reporting.unhcr.org/rwanda (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Relief Web. UNHCR Rwanda: Mugombwa Refugee Camp Profile (as of 15 April 2021)—Rwanda. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/rwanda/unhcr-rwanda-mugombwa-refugee-camp-profile-15-april-2021 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- African Humanitarian Action. Prevalence of Teenage Pregnancy in Mugombwa Refugee Camp in 2022. unpublished raw data.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR]. Congolese Refugees: A Protracted Situation. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/558c0e039.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Hunting, G. Qualitative Research: A Primer Intersectionality-Informed; The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/10714283/intersectionality-informed-qualitative-research--a-primer (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Yazdkhasti, M.; Pourreza, A.; Pirak, A.; Abdi, F. Unintended Pregnancy and Its Adverse Social and Economic Consequences on Health System: A Narrative Review Article. Iran J. Public Health 2015, 44, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Okanlawon, K.; Reeves, M.; Agbaje, O.F. Contraceptive Use: Knowledge, Perceptions and Attitudes of Refugee Youths in Oru Refugee Camp, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2011, 14, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.H.; Muyinda, H.; Sewankambo, N.K.; Oyat, G.; Atim, S.; Spittal, P.M. In the face of war: Examining sexual vulnerabilities of Acholi adolescent girls living in displacement camps in conflict-affected Northern Uganda. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2012, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Zambia. Knowledge and Use of Sexual Reproductive Health and HIV Services among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in Central and Western Provinces: A Qualitative Knowledge Attitudes and Practices Study. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/zambia/media/2461/file/Zambia-SRH-KAP-research-brief-2021.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Khuzwayo, N.; Taylor, M. Exploring the socio-ecological levels for prevention of sexual risk behaviors of the youth in uMgungundlovu District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2018, 10, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion. National Integrated Child Rights Policy. 2011. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/94113/110347/F-1184355681/RWA-94113.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Rwanda. Law No. 51/2018, on Prevention, Suppression and Punishment of Trafficking in Persons and Exploitation of Others. Available online: https://rwandalii.africanlii.org/sites/default/files/gazette/OG%2Bno%2B39%2Bof%2B24%2B9%2B18%2B1.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Rwanda. Law No. 13/2009, Regulating Labour in Rwanda. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/SERIAL/81725/89012/F-1047050984/RWA-81725.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR]. A Framework for the Protection of Children. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/50f6cf0b9.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Mulugeta, T. (African Humanitarian Action, Rwanda); Sibomama, E. (African Humanitarian Action, Rwanda). Personal communication. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ritterman Weintraub, M.L.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Adler, N.; Bertozzi, S.; Syme, S.L. Perceptions of social mobility: Development of a new psychosocial indicator associated with adolescent risk behaviors. Front. Public Health 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O.; Rai, M.; Mlahagwa, W.; Tumuhairwe, J.; Bakuli, A.; Nyakato, V.N.; Kemigisha, E. A cross-sectional mixed-methods study of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences and access to services among refugee adolescent girls in the Nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kågesten, A.E.; Zimmerman, L.; Robinson, C.; Lee, C.; Bawoke, T.; Osman, S.; Schlecht, J. Transitions into puberty and access to sexual and reproductive health information in two humanitarian settings: A cross-sectional survey of very young adolescents from Somalia and Myanmar. Confl. Health 2017, 11, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korri, R.; Hess, S.; Froeschl, G.; Ivanova, O. Sexual and reproductive health of Syrian refugee adolescent girls: A qualitative study using focus group discussions in an urban setting in Lebanon. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenwaka, U.; Mbachu, C.; Ezumah, N.; Eze, I.; Agu, C.; Agu, I.; Onwujekwe, O. Exploring factors constraining utilization of contraceptive services among adolescents in Southeast Nigeria: An application of the socio-ecological model. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, S.; Manu, A.; Morhe, E.; Dalton, V.K.; Loll, D.; Dozier, J.; Zochowski, M.K.; Boakye, A.; Adanu, R.; Hall, K.S. Multiple levels of social influence on adolescent sexual and reproductive health decision-making and behaviors in Ghana. Women Health 2017, 58, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingeta, T.; Oljira, L.; Worku, A.; Berhane, Y. Low contraceptive utilization among young married women is associated with perceived social norms and belief in contraceptive myths in rural Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, L.M.; Mirzoyants, A.; Thuku, S.; Benova, L.; Delvaux, T.; van den Akker, T.; McGuire, C.; Onyango, B.; Speizer, I.S. Perceptions of peer contraceptive use and its influence on contraceptive method use and choice among young women and men in Kenya: A quantitative cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.L.; Rushwan, H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: The global challenges. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 131, S40–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinaro, J.W.; Wangalwa, G.; Karanja, S.; Adika, B.; Lengewa, C.; Masitsa, P. Socio-Cultural Barriers Influencing Utilization of Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) Information and Services among Adolescents and Youth 10-24 Years in Pastoral Communities in Kenya. Adv. Sex. Med. 2019, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, L.M.; Parkes, A.; Wight, D.; Petticrew, M.; Hart, G.J. Limits to modern contraceptive use among young women in developing countries: A systematic review of qualitative research. Reprod. Health 2009, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinaro, J.; Kimani, M.; Ikamari, L.; Ayiemba, E.H.O. Perceptions and Barriers to Contraceptive Use among Adolescents Aged 15-19 Years in Kenya: A Case Study of Nairobi. Health 2015, 07, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbadu Muanda, F.; Gahungu, N.P.; Wood, F.; Bertrand, J.T. Attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health among adolescents and young people in urban and rural DR Congo. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrumpf, L.A.; Stephens, M.J.; Nsarko, N.E.; Akosah, E.; Baumgartner, J.N.; Ohemeng-Dapaah, S.; Watt, M.H. Side effect concerns and their impact on women’s uptake of modern family planning methods in rural Ghana: A mixed methods study. BMC Women Health 2020, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond-Smith, N.; Campbell, M.; Madan, S. Misinformation and fear of side-effects of family planning. Cult. Health Sex. 2012, 14, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Aules, Y.; Sami, S.; Lar, P.K.; Schlect, J.; Robinson, C. Sexual and reproductive health needs and risks of very young adolescent refugees and migrants from Myanmar living in Thailand. Confl. Health 2011, 11 (Suppl. S1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isimbi, R.; Mwali, M.M.; Ngabo, E.; Coast, E. ‘I No Longer Have a Hope of Studying’: Gender Norms, Education and Wellbeing of Refugee Girls in Rwanda; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; Chapter 6; pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Rwanda. National Family Planning and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health (FP/ASRH) Strategic Plan (2018–2024). Available online: https://moh.prod.risa.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Moh/Publications/Strategic_Plan/Rwanda_Adolescent_Strategic_Plan_Final.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Rwanda. Adolescent SRHR IEC Material for 10–14 year-olds. 2018; Pamphlet. [Google Scholar]

- Tilahun, M.; Mengistie, B.; Egata, G.; Reda, A.A. Health workers’ attitudes toward sexual and reproductive health services for unmarried adolescents in Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 2012, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton-Levinson, A.; Leichliter, J.S.; Chandra-Mouli, V. Sexually Transmitted Infection Services for Adolescents and Youth in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Perceived and Experienced Barriers to Accessing Care. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.; George, A.S.; Jacobs, T.; Blanchet, K.; Singh, N.S. A forgotten group during humanitarian crises: A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people including adolescents in humanitarian settings. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmine, R.; Moughalian, C. Systemic violence against Syrian refugee women and the myth of effective intrapersonal interventions. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eastman, A.; Olunuga, O.; Moges, T. Socio-Cultural Barriers Influencing Unplanned Pregnancy in Mugombwa Refugee Camp, Rwanda: Female Adolescents’ Perspectives. Adolescents 2023, 3, 259-277. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020019

Eastman A, Olunuga O, Moges T. Socio-Cultural Barriers Influencing Unplanned Pregnancy in Mugombwa Refugee Camp, Rwanda: Female Adolescents’ Perspectives. Adolescents. 2023; 3(2):259-277. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleEastman, Autumn, Oluwatomi Olunuga, and Tayechalem Moges. 2023. "Socio-Cultural Barriers Influencing Unplanned Pregnancy in Mugombwa Refugee Camp, Rwanda: Female Adolescents’ Perspectives" Adolescents 3, no. 2: 259-277. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020019

APA StyleEastman, A., Olunuga, O., & Moges, T. (2023). Socio-Cultural Barriers Influencing Unplanned Pregnancy in Mugombwa Refugee Camp, Rwanda: Female Adolescents’ Perspectives. Adolescents, 3(2), 259-277. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents3020019