Pathways to Criminal Hacking: Connecting Lived Experiences with Theoretical Explanations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Exploring Cybercrime Pathways

1.2. Theoretical Explanations of Hacking Behavior

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.4. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Personality and Early Childhood Experiences

3.1.1. Quiet, Creative, Anxious

3.1.2. Destabilizing Events

3.2. Familial Alienation

3.3. Early Interest in Technology

3.4. Significant Time Spent Online

3.5. The Juxtaposition of Unlimited Freedom and Power and Control

3.6. Computer as a Safe Haven

3.7. Academic Struggles

3.8. Participants in the World of Gaming

From Cheating/Modifying Games to Hacking

3.9. The Influence of Online Forums and Friends

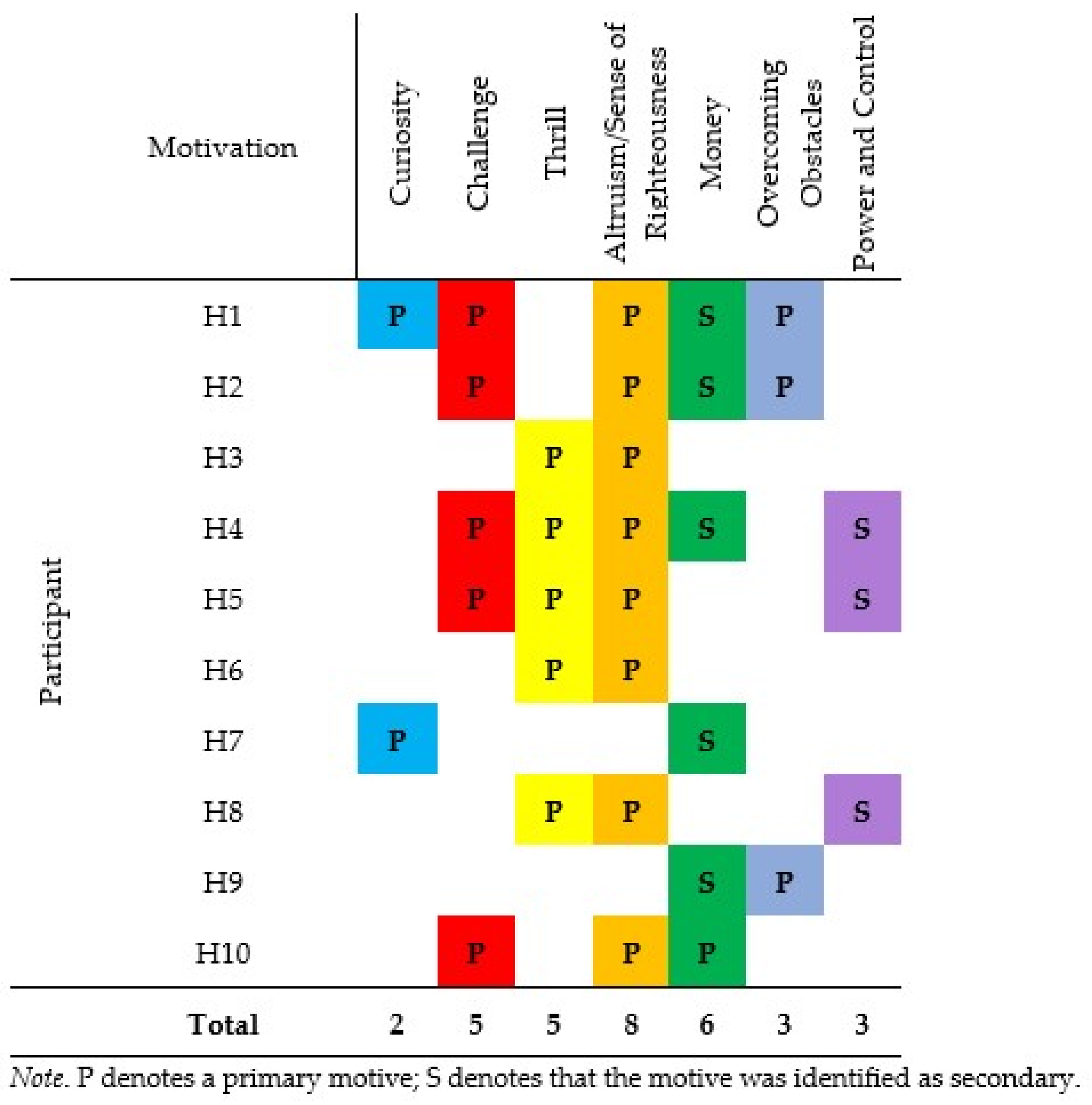

3.10. Motivated by Curiosity, Challenge, Thrill, and Money

3.11. Being Part of the Elite

3.12. Hacking as a Game—The Abstraction of Victimization

3.13. The Biology and Mental Health Connection

4. Discussion

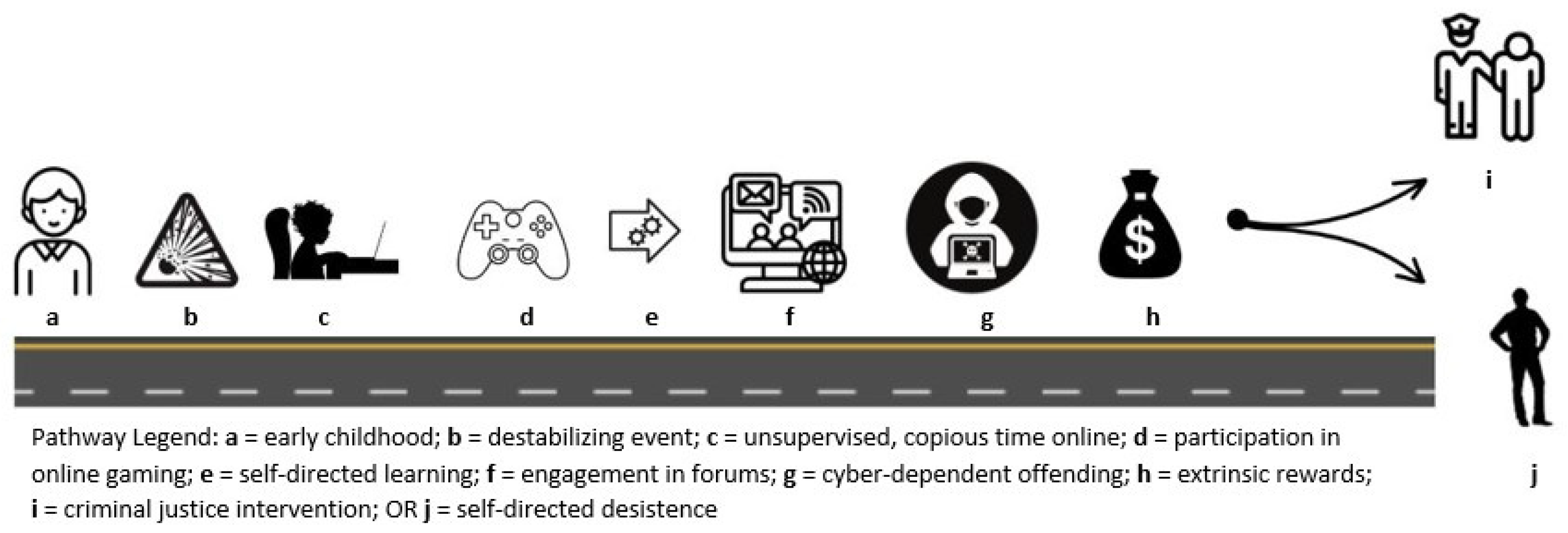

4.1. Pathway to Criminal Hacking

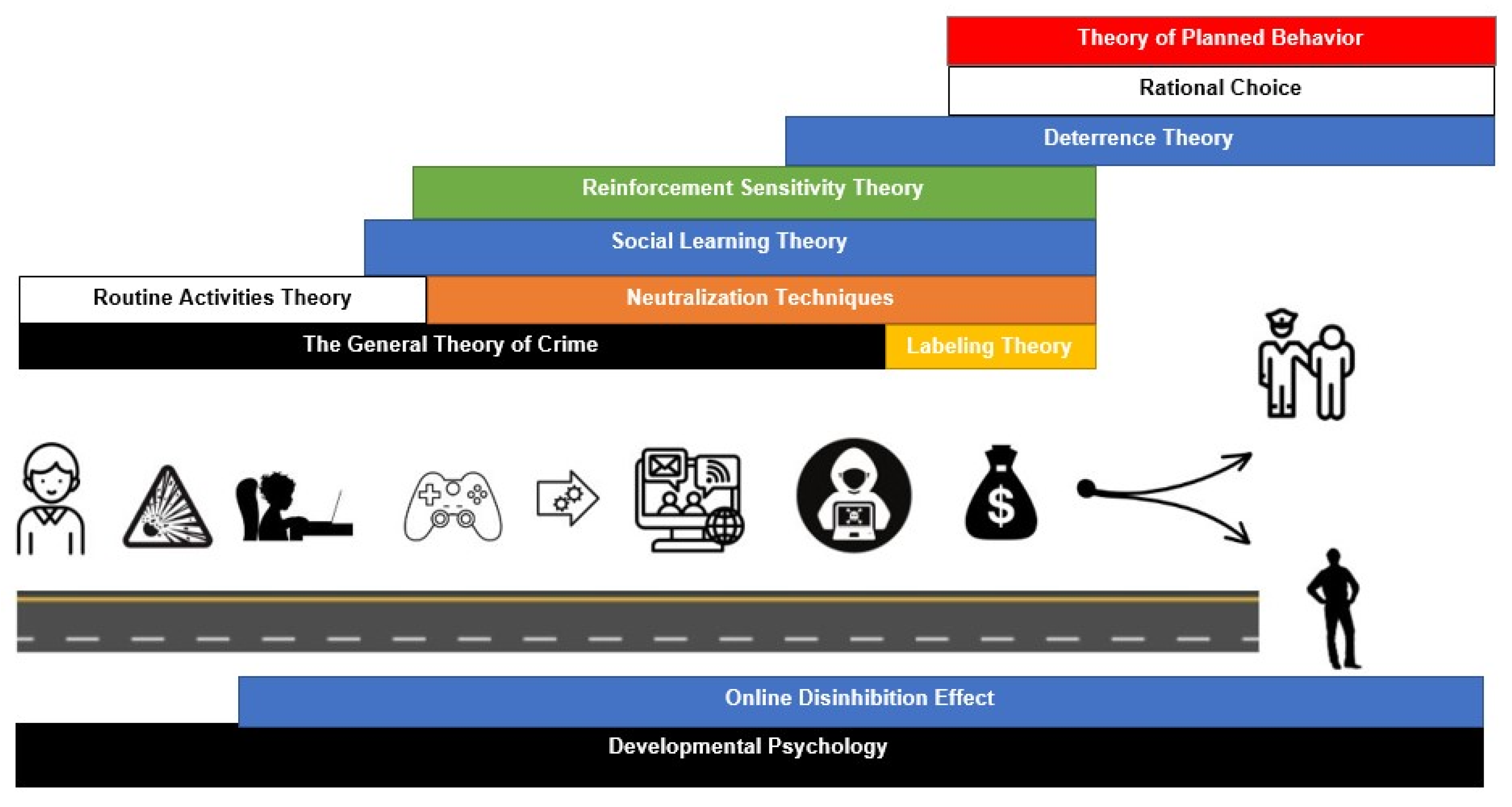

4.2. Integration of Theories to Explain the Hacking Pathway

4.3. Implications, Study Limitations, and Future Research

4.3.1. Implications

4.3.2. Study Limitations

4.3.3. Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baseline Cyber Threat Assessment: Cybercrime—Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. Available online: https://www.cyber.gc.ca/en/guidance/baseline-cyber-threat-assessment-cybercrime (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Kavanagh, C. New Tech, New Threats, and New Governance Challenges: An Opportunity to Craft Smarter Responses? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Working Paper, 2019. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2019/08/new-tech-new-threats-and-new-governance-challenges-an-opportunity-to-craft-smarter-responses?lang=en (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Chng, S.; Lu, H.Y.; Kumar, A.; Yau, D. Hacker types, motivations and strategies: A comprehensive framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2022, 5, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundie, M.; Lindke, K.; Amos-Binks, A.; Aiken, M.P.; Janosek, D. The Enterprise Strikes Back: Conceptualizing the HackBot -Reversing Social Engineering in the Cyber Defense Context. Available online: https://isss.ch/resources/site-media/2024/05/The-Enterprise-Strikes-Back-pdf.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Aiken, M.P. The Utility of cyberpsychology and forensic cyberpsychology. In Forensic Psychology: Crime, Justice, Law, Interventions; Davies, G.M., Beech, A.R., Colloff, M.F., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 715–719. ISBN 978-1-119-89202-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, M.S.; Aiken, M.P. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Enhancing Cyber Threat Prediction Utilizing Forensic Cyberpsychology and Digital Forensics. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 110–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, M.; Spiridon, E.; Aiken, M. A Comprehensive Framework for Cyber Behavioral Analysis Based on a Systematic Review of Cyber Profiling Literature. Forensic Sci. 2023, 3, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, R.; Cale, J.; Goldsmith, A.; Holt, T. Young People, the Internet, and Emerging Pathways into Criminality: A Study of Australian Adolescents. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2018, 12, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.; Davidson, J.C.; Farr, R.R.; Burkhardt, C.; Caneppele, S.; Aiken, M.P. Conceptualizing Cybercrime: Definitions, Typologies and Taxonomies. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, C.M.; Marcum, C.D.; Jennings, W.G.; Higgins, G.E.; Banfield, J. Low self-control and cybercrime: Exploring the utility of the general theory of crime beyond digital piracy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, D. Can the General Theory of Crime Account for Computer Offenders: Testing Low Self-Control as a Predictor of Computer Crime Offending; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2004; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Can-the-general-theory-of-crime-account-for-Testing-Foster/8759bb3f9f984c0f4be2093dc3cec189a4e985e6 (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Kerstens, J.; Jansen, J. The Victim–Perpetrator Overlap in Financial Cybercrime: Evidence and Reflection on the Overlap of Youth’s On-Line Victimization and Perpetration. Deviant Behav. 2016, 37, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loggen, J.; Moneva, A.; Leukfeldt, R. A systematic narrative review of pathways into, desistance from, and risk factors of financial-economic cyber-enabled crime. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2024, 52, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcum, C.D.; Higgins, G.E.; Ricketts, M.L.; Wolfe, S.E. Hacking in High School: Cybercrime Perpetration by Juveniles. Deviant Behav. 2014, 35, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, S.; Senadjki, A.; Rahim, S.R.M.; Nathan, T.M.; Lee, C.; Wahab, M.A. Cybercrime among malaysian youth. Asia Pac. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 15, 17–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, F.T.; Paternoster, R. Cybercrime victimization: An examination of individual and situational level factors. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2011, 5, 773. [Google Scholar]

- Leukfeldt, E.R.; Yar, M. Applying Routine Activity Theory to Cybercrime: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Deviant Behav. 2016, 37, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. Psychology of Computer Criminals. In Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Institute Conference, St. Louis, MO, USA, 9–12 March 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P. Hackers: Crime and the Digital Sublime; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; ISBN 0-203-20150-7. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, C. Why computer talents become computer hackers. Commun. ACM 2013, 56, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppre, B.; Salisbury, E.J.; Parker, J. Pathways to Crime. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-026407-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, M.P.; Davidson, J.; Amann, P. Youth Pathways into Cybercrime. 2016. Available online: https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-documents/youth-pathways-cybercrime (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Aiken, M.P.; Davidson, J.C.; Walrave, M.; Ponnet, K.S.; Phillips, K.; Farr, R.R. Intention to Hack? Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Youth Criminal Hacking. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.; Aiken, M.P.; Phillips, K.; Farr, R. CC-Driver 2022 Research Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.ccdriver-h2020.com/_files/ugd/0ef83d_a8b9ac13e0cf4613bc8f150c56302282.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Kranenbarg, M.W.; van der Toolen, Y.; Weerman, F. Understanding Cybercriminal Behaviour Among Young People: Results from a Longitudinal Network Study Among a Relatively High-Risk Sample; VU University Amsterdam/Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maras, K.; Sweiry, A.; Villadsen, A.; Fitzsimons, E. Cyber offending predictors and pathways in middle adolescence: Evidence from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 151, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Crime Agency. Intelligence Assessment Youth Pathways into Cyber Crime in the UK for Serious and Organised Crime NAC National Assessments Centre Key Findings. 2022. Available online: https://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/who-we-are/publications/596-nac-youth-pathways-into-cyber-crime/file (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- National Crime Agency. Intelligence Assessment National Cyber Crime Unit/Prevent Team Pathways Into Cyber Crime. 2017. Available online: https://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/who-we-are/publications/6-pathways-into-cyber-crime-1/file (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Goldsmith, A.; Wall, D.S. The seductions of cybercrime: Adolescence and the thrills of digital transgression. Eur. J. Criminol. 2022, 19, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.J.; Navarro, J.N.; Clevenger, S. Exploring the Moderating Role of Gender in Juvenile Hacking Behaviors. Crime Delinq. 2020, 66, 1533–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, K.F. Becoming a Hacker: Demographic Characteristics and Developmental Factors. J. Qual. Crim. Justice Criminol. 2015, 3, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissink, I.B.; Standaert, J.C.A.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Asscher, J.J.; Assink, M. Risk factors for juvenile cybercrime: A meta-analytic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2023, 70, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Crime Agency. National Crime Agency Identify, Intervene, Inspire: Helping Young People to Pursue Careers in Cyber Security, Not Cyber Crime. 2015. Available online: https://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/who-we-are/publications/623-cyber-crime-report-crest-nca/file (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Loeber, R.; Le Blanc, M. Toward a developmental criminology. Crime Justice 1990, 12, 375–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, K.F. Craft(y)ness: An Ethnographic Study of Hacking. Br. J. Criminol. 2015, 55, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M. Deciphering the hacker underground: First quantitative insights. In Cyber Crime: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, T.J. Becoming a computer hacker: Examining the enculturation and development of computer deviants. In In Their Own Words: Criminals on Crime: An Anthology; Cromwell, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, B.H.; Holt, T.J. A profile of the demographics, psychological predispositions, and social/behavioral patterns of computer hacker insiders and outsiders. In Online Consumer Protection: Theories of Human Relativism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 190–213. [Google Scholar]

- Grabosky, P.N. Virtual Criminality: Old Wine in New Bottles? Soc. Leg. Stud. 2001, 10, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, M. Computer Hacking: Just Another Case of Juvenile Delinquency? Howard J. Crim. Justice 2005, 44, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D. Cybercrimes: New Wine, No Bottles? In Invisible Crimes; Davies, P., Francis, P., Jupp, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 1999; pp. 105–139. ISBN 978-0-333-79417-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, B.; Bachmann, M. Out of the Beta Phase: Obstacles, Challenges, and Promising Paths in the Study of Cyber Criminology. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2015, 9, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaishankar, K. Space transition theory of cyber crimes, crimes of the internet. In Crimes of the Internet; Schmalleger, F., Pittaro, M., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, UK, 2008; pp. 283–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson, M.R.; Hirschi, T. A General Theory of Crime; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-8047-1773-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.E.; Felson, M. Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, R.L. Deviant Behavior: A Social Learning Approach; Wadsworth Publishing Company: Belmont, CA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-534-03915-8. [Google Scholar]

- Akers, R.L. Social Learning and Social Structure; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-3-642-69748-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Ltd.: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; ISBN 978-0-201-02089-2. Available online: http://archive.org/details/beliefattitudein0000fish (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Gray, J.A. Causal theories of personality and how to test them. Multivar. Anal. Psychol. Theory 1973, 16, 302–354. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7879-5140-5. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, 1st ed.; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-06-133920-2. [Google Scholar]

- Suler, J. The Online Disinhibition Effect. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, M. The Cyber Effect: A Pioneering Cyber-Psychologist Explains How Human Behavior Changes Online; Random House Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-8129-9785-9. [Google Scholar]

- Back, S.; Soor, S.; LaPrade, J. Juvenile Hackers: An Empirical Test of Self-Control Theory and Social Bonding Theory. Int. J. Cybersecurity Intell. Cybercrime 2018, 1, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, R.C. Crime by computer: Correlates of software piracy and unauthorized account access. Secur. J. 1993, 4, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, W.F.; Fream, A.M. A Social Learning Theory Analysis of Computer Crime among College Students. J. Res. Crime Delinquency 1997, 34, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodeland, B.; Morris, R. A Test of Social Learning Theory and Self-Control on Cyber Offending. Deviant Behav. 2020, 41, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.K. A Social Learning Theory and Moral Disengagement Analysis of Criminal Computer Behavior: An Exploratory Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA, USA, 2001. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304732918?fromunauthdoc=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Young, R.; Zhang, L.; Prybutok, V.R. Hacking into the Minds of Hackers. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2007, 24, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, L.; Shore, M. An advanced model of hacking. Secur. J. 2007, 20, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.; Ma, Q. Convergence of Virus Writers and Hackers: Fact or Fantasy; Symantec Security White Paper; Symantec Security: Cupertine, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, M.; Shortland, N.; McGarry, P. Personality and online deviance: The role of reinforcement sensitivity theory in cybercrime. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 120, 106745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveren, J.V. A conceptual model of hacker development and motivations. J. E-Bus. 2001, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, H.-J. The Hacker Mentality: Exploring the Relationship between Psychological Variables and Hacking Activities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Assarut, N.; Bunaramrueang, P.; Kowpatanakit, P. Clustering Cyberspace Population and the tendency to Commit Cyber Crime: A Quantitative Application of Space Transition Theory. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2019, 13, 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, M.J.H. Decrypting Personality: The Effects of Motivation, Social Power, and Anonymity on Cybercrime. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2724700785/abstract/6DC83908D7DC4F34PQ/1 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Fox, B.; Holt, T.J. Use of a Multitheoretic Model to Understand and Classify Juvenile Computer Hacking Behavior. Crim. Justice Behav. 2021, 48, 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Leban, L.; Lee, Y. Theoretical explanations of the development of youth hacking. Crime Delinq. 2024, 70, 1971–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4129-4163-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.J. Cyber-Ethnography and the Emergence of the Virtually New Community. J. Inf. Technol. 1999, 14, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-5264-1729-9. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, J. How to Do Thematic Analysis|Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/thematic-analysis/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Worthington, R.; Wheeler, S. Hyperfocus and offending behaviour: A systematic review. J. Forensic Pract. 2022, 25, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.J. Subcultural evolution? Examining the influence of on- and off-line experiences on deviant subcultures. Deviant Behav. 2007, 28, 171–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.E. Hacking into Hacking: Gender and the Hacker Phenomenon. ACM SIGCAS Comput. Soc. 2003, 33, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asam, A.; Katz, A. Vulnerable young people and their experience of online risks. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 33, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakarian, J.; Gunn, A.T.; Shakarian, P. Exploring Malicious Hacker Forums. In Cyber Deception; Jajodia, S., Subrahmanian, V.S., Swarup, V., Wang, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 259–282. ISBN 978-3-319-32697-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, G.M.; Matza, D. Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1957, 22, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.S. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance; Free Press Glencoe: Oxford, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Leukfeldt, E.R. Research Agenda the Human Factor in Cybercrime and Cybersecurity; Eleven International Publishing: Hague, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 94-6274-706-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou, K. What Is Response Bias?|Definition & Examples. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/research-bias/response-bias/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martineau, M.; Spiridon, E.; Aiken, M. Pathways to Criminal Hacking: Connecting Lived Experiences with Theoretical Explanations. Forensic Sci. 2024, 4, 647-668. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040045

Martineau M, Spiridon E, Aiken M. Pathways to Criminal Hacking: Connecting Lived Experiences with Theoretical Explanations. Forensic Sciences. 2024; 4(4):647-668. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040045

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartineau, Melissa, Elena Spiridon, and Mary Aiken. 2024. "Pathways to Criminal Hacking: Connecting Lived Experiences with Theoretical Explanations" Forensic Sciences 4, no. 4: 647-668. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040045

APA StyleMartineau, M., Spiridon, E., & Aiken, M. (2024). Pathways to Criminal Hacking: Connecting Lived Experiences with Theoretical Explanations. Forensic Sciences, 4(4), 647-668. https://doi.org/10.3390/forensicsci4040045