The Identity of Crambe suecica (Brassicaceae), an Obscure Garden Plant That Caused Nomenclatural Chaos in Taxonomic Botany

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Protologue of Crambe suecica

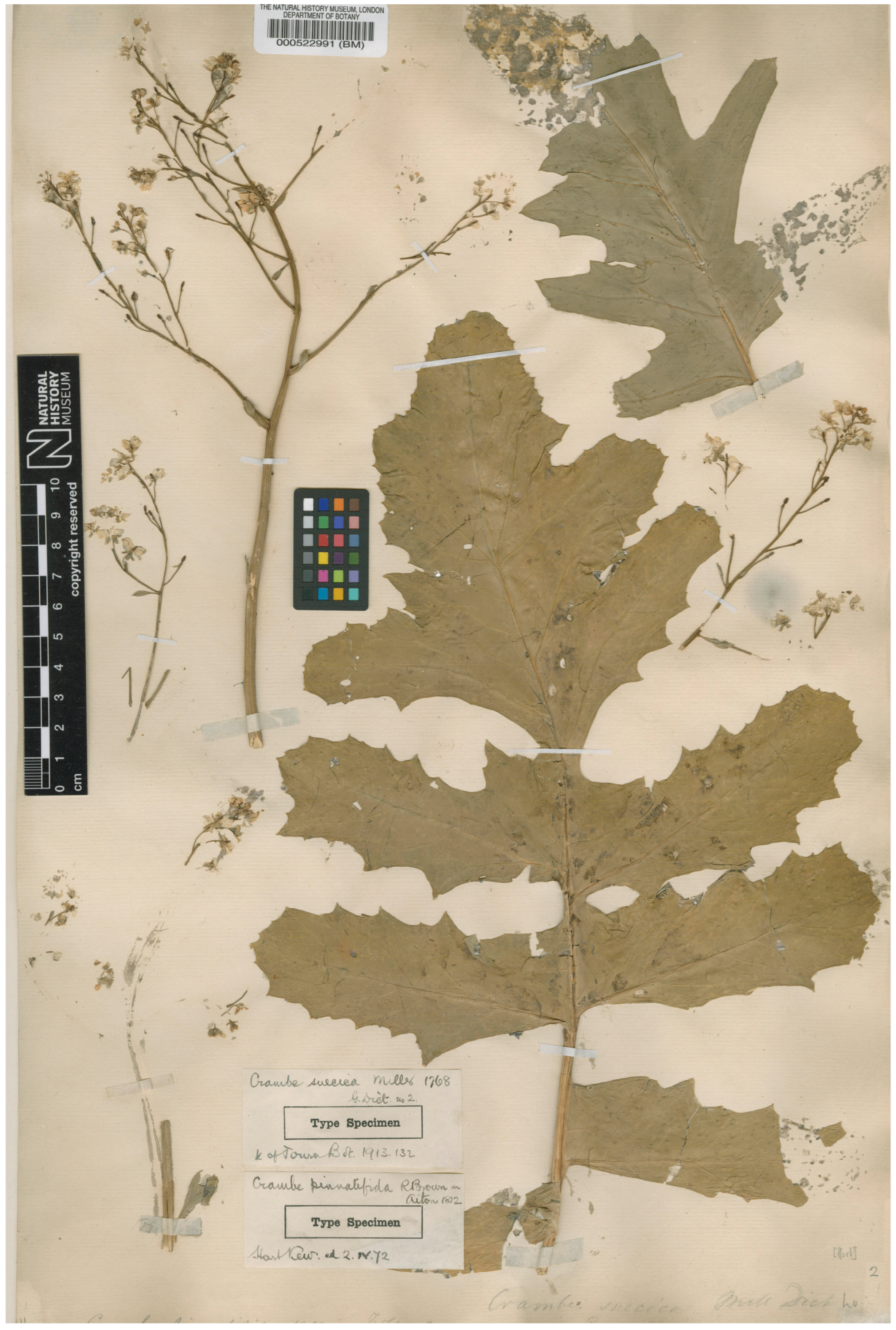

3.2. Original Material of Crambe suecica

3.3. Protologue of Crambe pinnatifida

3.4. Formal Nomenclature of Crambe suecica

4. Discussion

4.1. Taxonomic System of Crambe in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus

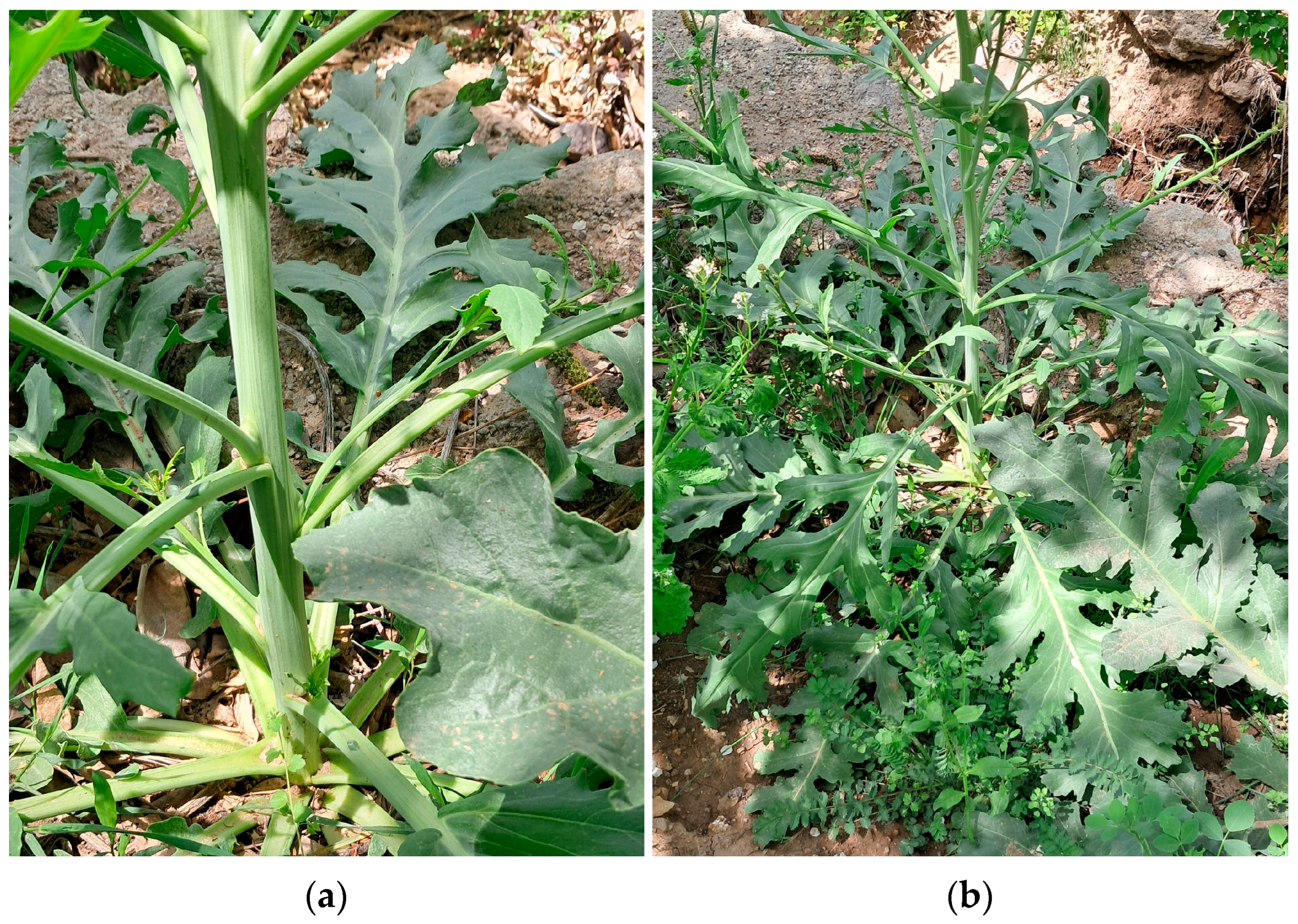

4.2. Taxonomic Position of Crambe suecica

4.3. Geographic Origin of Crambe suecica

4.4. Taxonomic Identities of Crambe pinnatifida

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peruzzi, L. Some claim for the end of Botany… but what is Botany today? Ital. Bot. 2025, 19, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakow, D.A.; Lee, S.A. Western botanical gardens: History and evolution. Hortic. Rev. 2015, 43, 269–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-H. Everlasting Flowers Between the Pages: Forms of Knowledge and the Making of Seventeenth-Century Florilegia; University of Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 978-90-04-73513-2. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, N. Hortus Eystettensis: The Bishop’s Garden and Besler’s Magnificent Book; H.N. Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8109-3424-5. [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo, G.; Offerhaus, A.; van Andel, T.; Stefanaki, A. How the wild tulip (Tulipa sylvestris L.) found its way in Northern Europe in the 17th to 19th century: A search through historical gardens and archives. Bot. Lett. 2025, 172, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambdon, P.W.; Pyšek, P.; Basnou, C.; Hejda, M.; Arianoutsou, M.; Essl, F.; Jarošík, V.; Pergl, J.; Winter, M.; Anastasiu, P.; et al. Alien flora of Europe: Species diversity, temporal trends, geographical patterns and research needs. Preslia 2008, 80, 101–149. [Google Scholar]

- Galera, H.; Sudnik-Wójcikowska, B. Central European botanic gardens as centres of dispersal of alien plants. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2010, 79, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, A.N.; Kurtto, A. The taxonomy and invasion status assessment of Erigeron annuus s.l. (Asteraceae) in East Fennoscandia. Memo. Soc. Fauna Fl. Fenn. 2019, 95, 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Hortus Cliffortianus: Plantas Exhibens quas in Hortis tam Vivis Quam Siccis, Hartecampi in Hollandia; Privately Published: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaeus, C. Genera Plantarum; C. Wishoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1737. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Species Plantarum; L. Salvius: Stockholm, Sweden, 1753. [Google Scholar]

- Stafleu, F.A. Linnaeus and the Linnaeans: The Spreading of THEIR Ideas in Systematic Botany, 1735–1789; Oosthoek: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1971; ISBN 90-6046-064-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, C. Order out of Chaos. Linnean Plant Names and Their Types; The Linnean Society of London & the Natural History Museum: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-9506207-7-0. [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus, C. Hortus Upsaliensis L.; Salvius: Stockholm, Sweden, 1748. [Google Scholar]

- Rowell, M. Linnaeus and botanists in eighteenth-century Russia. Taxon 1980, 29, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, W.J. A Botanist’s Paradise: The Establishment of Scientific Botany in Russia in the Eighteenth Century; W.J. Bryce: Sketty Swansea, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-9560-3580-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer von Waldheim, A.A. (Ed.) Imperial Botanical Garden in Saint Petersburg During Its 200 Years (1713–1913); Imperial Botanical Garden: Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, 1913. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shetler, S.G. The Komarov Botanical Institute: 250 Years of Russian Research; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, A.N. The history and nomenclatural significance of herbarium collections made by Alexander A. Tatarinow in North China and Mongolia in 1841–1850. Taxon 2024, 73, 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloove, F.; Sennikov, A.N.; Reyes-Betancort, J.A. Taxonomy and nomenclature of Abutilon albidum (Malvaceae, Malvoideae), a cryptic Saharo-Canarian species recently rediscovered in Tenerife. PhytoKeys 2023, 221, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Figueiredo, E. Out with the old, in with the new? Historical names recorded in Agave L. (Agavaceae/Asparagaceae). Bradleya 2014, 32, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Klopper, R.R.; Figueiredo, E.; Crouch, N.R.; Barkworth, M.E. A note on four historical names recorded in Aloe L. (Asphodelaceae: Alooideae). Bradleya 2013, 31, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Calonje, M.; Sennikov, A.N. In the process of saving plant names from oblivion: The revised nomenclature of Ceratozamia fuscoviridis (Zamiaceae). Taxon 2017, 66, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, A.N.; Khassanov, F.O.; Lazkov, G.A. The nomenclatural history of Iris orchioides (Iridaceae). Memo. Soc. Fauna Fl. Fenn. 2022, 98, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lazkov, G.A.; Sennikov, A.N. Taxonomy of two blue-flowered juno irises (Iris subgen. Scorpiris, Iridaceae) from the Western Tian-Shan. Ann. Bot. Fennici 2017, 54, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaerts, R.; Nic Lughadha, E.; Black, N.; Turner, R.; Paton, A. The World Checklist of Vascular Plants, a continuously updated resource for exploring global plant diversity. Sci. Data 2021, 8, e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellenberger Costa, D.; Boehnisch, G.; Freiberg, M.; Govaerts, R.; Grenié, M.; Hassler, M.; Kattge, J.; Muellner-Riehl, A.N.; Rojas Andrés, B.M.; Winter, M.; et al. The big four of plant taxonomy—A comparison of global checklists of vascular plant names. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 1687–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Rougetel, H. The Chelsea Gardener: Philip Miller, 1691–1771; Natural History Museum Publications: London, UK, 1990; ISBN 0565011014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. Gardener’s Dictionary, 8th ed.; Printed for the Author: London, UK, 1768. [Google Scholar]

- Prina, A. Taxonomic review of the genus Crambe sect. Crambe (Brassicaceae, Brassiceae). An. Jard. Bot. Madr. 2009, 66, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Aiton, W.T. Hortus Kewensis, 2nd ed.; Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown: London, UK, 1812; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Turland, N.J.; Wiersema, J.H.; Barrie, F.R.; Gandhi, K.N.; Gravendyck, J.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Klopper, R.R.; Knapp, S.; et al. (Eds.) International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants (Madrid Code); Regnum Vegetabile 162; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dorofeev, V.I. Brassicaceae Burnett. In Caucasian flora Conspectus; Takhtajan, A.L., Ed.; KMK Scientific Press: Moscow, Russia; Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2012; Volume 3, part 2; pp. 371–469. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Dorofeev, V.I. Brassicaceae Burnett. In Conspectus florae Europae Orientalis; Tzvelev, N.N., Ed.; KMK Scientific Press: Moscow, Russia; Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 364–437. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- De Natale, A.; Cellinese, N. Imperato, Cirillo, and a series of unfortunate events: A novel approach to assess the unknown provenance of historical herbarium specimens. Taxon 2009, 58, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, W.J. Russian collections in the Sloane Herbarium. Arch. Nat. Hist. 2005, 32, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, S.; Sennikov, A.N. Taxonomic evaluation of the illegitimate and ill-defined Crambe pinnatifida (Brassicaceae), with new synonymy and the description of C. euxina, a new species of the northern Pontic distribution. Nordic J. Bot. 2026; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. Gardener’s Dictionary, 7th ed.; Printed for the Author: London, UK, 1759. [Google Scholar]

- Natural History Museum. Crambe pinnatifida R.Br. (from Collection Specimens) [Photograph]. Natural History Museum. Available online: https://data.nhm.ac.uk/object/041e61e7-156b-46ce-a20d-96b4f4a941e1/1760005475174 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

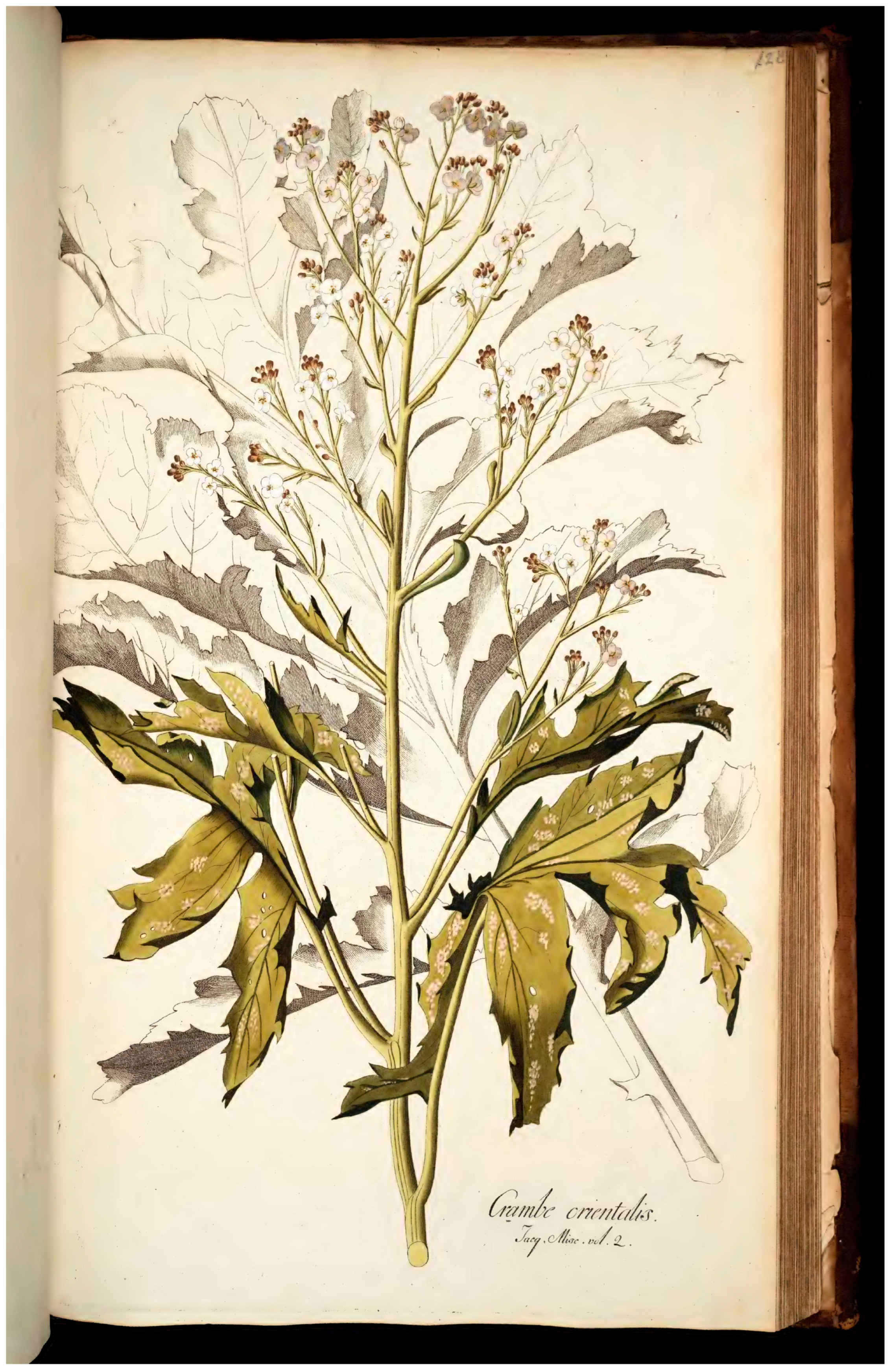

- Jacquin, N.J. Icones Plantarum Rariorum; Wappler: Wien, Austria; B. White et Filium: London, UK; S. et J. Luchtmans: Leiden, The Netherlands; A. König: Strasbourg, France, 1784; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Khalilov, I.I. A synopsis of the genus Crambe (Braccicaceae). Bot. Zhurn. 1993, 78, 107–115. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Francisco-Ortega, J.; Fuertes-Aguilar, J.; Gómez-Campo, C.; Santos-Guerra, A.; Jansen, R.K. Internal transcribed spacer sequence phylogeny of Crambe L. (Brassicaceae): Molecular data reveal two Old World disjunctions. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1999, 11, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacioğlu, B.T.; Özgişi, K. Haplotype diversity and molecular phylogeny of wild Crambe L. (Brassicaceae) taxa of Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 2023, 47, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, I. Cruciferae–Brassiceae. In Flora Iranica; Rechinger, K.H., Ed.; Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt: Graz, Austria, 1968; Volume 57, pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sennikov, A.N.; Lazkov, G.A. Alien plants of Kyrgyzstan: The first complete inventory, distributions and main patterns. Plants 2024, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennikov, A.N.; Lazkov, G.A.; German, D.A. The first checklist of alien vascular plants of Kyrgyzstan, with new records and critical evaluation of earlier data. Contribution 3. Biodivers. Data J. 2025, 13, e145624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, N.A. Cruciferae asiaticae novae. Vĕstn. Tiflissk. Bot. Sada Nov. Ser. 1927, 3–4, 1–12. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bornmüller, J. Beiträge zur Flora der Elbursgebirge Nord-Persiens. Bull. Herbier Boissier 2 Ser. 1905, 5, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Popovich, A.V.; Zernov, A.S. A new nothospecies of Crambe L. (Cruciferae) from the North-Western Transcaucasia. Turczaninowia 2019, 22, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavaev, M.N. At the sources of floristics and herbarium art in Russia (according to the materials of the Moscow University Herbarium). Byull. Mosk. Obshch. Ispyt. Prir. Biol. 1981, 86(5), 126–133. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, D.D.; Balandin, S.A.; Gubanov, I.A.; Jarvis, C.E.; Majorov, S.R.; Simonov, S.S. The history of botany in Moscow and Russia in the 18th and early 19th centuries in the context of the Linnean Collection at Moscow University. Huntia 2002, 11, 129–191. [Google Scholar]

- Polievktov, M.A. European Travellers of 13th–18th centuries in the Caucasus; Academy of Sciences of the USSR: Tiflis, USSR, 1935. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Fedtschenko, B.A. The investigators of the flora of Iran. Bot. Zhurn. 1945, 30, 31–43. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bushev, P.P. The Diplomatic Mission of Artemy Volynski to Iran in 1715–1718; Science Publishers: Moscow, USSR, 1978. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, V.I. Flora of the Caucasus, a Compendium of the Botany in the Caucasus During its 200-Years History, from Tournefort Till the 19th Century; Herold: Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, 1899. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- von Richter, W.M. Geschichte der Medicin in Russland; N.S. Wsewolojsky: Moscow, Russian Empire, 1817; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Grossheim, A.A. Flora of the Caucasus, 2nd ed.; Academy of Sciences of the USSR: Moscow, USSR; Leningrad, USSR, 1950; Volume 4. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lerche, J.J. Descriptio plantarum quarundam partim minus cognitarum astrachanensium et Persiae provinciarum Caspio Mari adiacentium iuxta methodum sexualem excellentissimi domini archiatri Caroli de Linne, accedit plantarum catalogus istarum regionum cum variis observationibus Io. Iac. Lerche. Nova Acta Phys.-Medica Acad. Caesareae Leopold.-Carol. Naturae Curiosorum 1773, 5, 161–206. [Google Scholar]

- Czerepanov, S.K. Vascular Plants of Russia and Adjacent States (the Former USSR); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marhold, K. Brassicaceae. Euro+Med PlantBase—The Information Resource for Euro-Mediterranean Plant Diversity. Available online: https://europlusmed.org/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Lerche, J.J. Lebens-und Reise-Geschichte, von Ihm Selbst Beschrieben; C. Witwe: Halle, Germany, 1791. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin, N.J. (Ed.) Observationes botanicae. In Miscellanea austriaca ad Botanicam, Chemiam, et Historiam Naturalem Spectantia, cum Figuris; Officina Krausiana: Vienna, Austria, 1781; Volume 2, pp. 292–379. [Google Scholar]

- de Candolle, A.P. Regni Vegetabilis Systema Naturale; Treuttel & Würtz: Paris, France, 1821; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Czerniakowska, E.G. Crambe L. In Flora of the USSR; Busch, N.A., Ed.; Academy of Sciences of the USSR: Moscow, USSR; Leningrad, USSR, 1939; Volume 8, pp. 474–491. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kotov, M.I. Brassicaceae Burnett. In Flora of the European Part of the USSR; Fedorov, A.A., Ed.; Science Publishers: Leningrad, USSR, 1979; Volume 4, pp. 30–148. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Busch, N.A. Cruciferae. In Flora Caucasica Critica; Kuznetsov, N., Busch, N., Fomin, A., Eds.; Mattiesen: Yuriev, Russian Empire, 1908; Volume 3, part 4. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Barina, Z. Brassicaceae (Cruciferae). In Új Magyar Füvészkönyv. Magyarország Hajtásos Növényei. Határozókulcsok és Ábrák, 2nd ed.; Király, G., Virók, V., Takács, A., Szmorad, F., Molnár, V.A., Eds.; Aggteleki Nemzeti Park Igazgatóság: Jósvafő, Hungary, 2025; pp. 188–212. [Google Scholar]

- Alefeld, F. Landwirthschaftliche Flora: Oder Die Nutzbaren Kultivirten Garten-und Feldgewächse Mitteleuropa’s in Allen Ihren Wilden und Kulturvarietäten für Landwirthe, Gartner, Gartenfreunde und Botaniker Insbesondere für Landwirthschaftliche Lehranstalten; Wiegandt & Hempel: Berlin, Germany, 1866. [Google Scholar]

- Schmalhausen, I.F. Flora of Central and Southern Russia, the Crimea and the Caucasus; Saint Vladimir University: Kiev, Russian Empire, 1895; Volume 1. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, O.E. Cruciferae–Brassiceae. Pars prima. Subtribus I. Brassicinae et II. Raphaninae. In Das Pflanzenreich. Regni Vegetabilis Conspectus; Engler, A., Ed.; W. Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1919; Volume 70, pp. 1–290. [Google Scholar]

- Lack, H.W. The discovery and naming of Papaver orientale s.l. (Papaveraceae) with notes on its nomenclature and early cultivation. Candollea 2019, 74, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Character | Crambe maritima Group | Crambe orientalis Group |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits, upper segment | 4–10 mm in diameter | 2.5–3(4) mm in diameter |

| Basal leaves, primary dissection | Entire to shallowly lobate, lobate to narrowly lobate, usually not pinnatisect | Entire to broadly lobate or pinnatisect |

| Basal leaves, secondary dissection | Lobes oblong to nearly linear, often further subdivided | Lobes oblong to broadly oblong, mostly undivided |

| Basal leaves, dentation | Margin undivided or with broad blunt to acute teeth | Often serrate, with acute-to-acuminate teeth |

| Inflorescence branches | Compact, rather thick | Lax, slender |

| Pedicels | Patent to divaricate | Suberect to appressed to the axis of racemes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sennikov, A.; Stoyanov, S. The Identity of Crambe suecica (Brassicaceae), an Obscure Garden Plant That Caused Nomenclatural Chaos in Taxonomic Botany. Taxonomy 2026, 6, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010014

Sennikov A, Stoyanov S. The Identity of Crambe suecica (Brassicaceae), an Obscure Garden Plant That Caused Nomenclatural Chaos in Taxonomic Botany. Taxonomy. 2026; 6(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleSennikov, Alexander, and Stoyan Stoyanov. 2026. "The Identity of Crambe suecica (Brassicaceae), an Obscure Garden Plant That Caused Nomenclatural Chaos in Taxonomic Botany" Taxonomy 6, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010014

APA StyleSennikov, A., & Stoyanov, S. (2026). The Identity of Crambe suecica (Brassicaceae), an Obscure Garden Plant That Caused Nomenclatural Chaos in Taxonomic Botany. Taxonomy, 6(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy6010014