Paired Flowers of Core Eudicots Discovered from Mid-Cretaceous Myanmar Amber †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Systematics

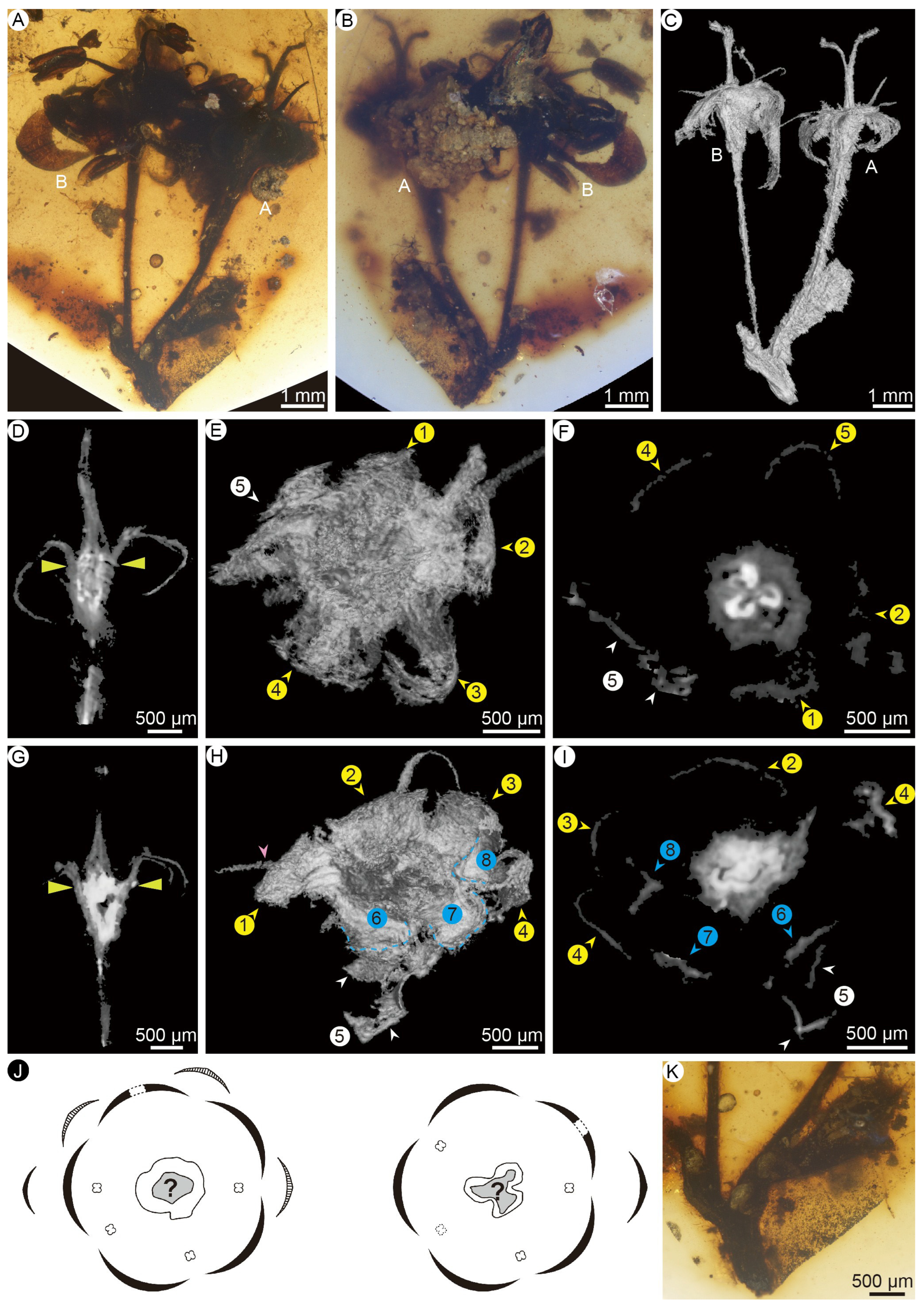

- Description

- Remarks

4. Discussion

4.1. Development of the Paired Flowers

4.2. Comparison with Extant Angiosperms

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Endress, P.K. Flower structure and trends of evolution in eudicots and their major subclades. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2010, 97, 541–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinar, G., Jr.; Chambers, K.L.; Buckley, R. Eoepigynia burmensis gen. and sp. nov., an early Cretaceous eudicot flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese Amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 2007, 1, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar, G., Jr.; Chambers, K.L.; Buckley, R. An early Cretaceous angiosperm fossil of possible significance in rosid floral diversification. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 2008, 2, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, K.; Poinar, G., Jr.; Buckley, R. Tropidogyne, a new genus of Early Cretaceous Eudicots (Angiospermae) from Burmese Amber. Novon 2010, 20, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinar, G.O., Jr.; Chambers, K.L. Tropidogyne pentaptera, sp. nov., a new mid-Cretaceous fossil angiosperm flower in Burmese amber. Palaeodiversity 2017, 10, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poinar, G.O., Jr.; Chambers, K.L. Tropidogyne lobodisca sp. nov., a third species of the genus from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber. J. Bot. Res. Inst. Tex. 2019, 13, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Huang, D.Y.; Cai, C.Y.; Wang, X. The core eudicot boom registered in Myanmar amber. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Pedersen, K.R.; Crane, P.R. The emergence of core eudicots: New floral evidence from the earliest Late Cretaceous. Proc. R. Soc. B 2016, 283, 20161325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, S.R.; Dilcher, D.L.; Judd, W.S.; Corder, B.; Basinger, J.F. Early Eudicot flower and fruit: Dakotanthus gen. nov. from the Cretaceous Dakota Formation of Kansas and Nebraska, USA. Acta Palaeobot. 2018, 58, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Yi, T.S.; Gao, L.M.; Ma, P.F.; Zhang, T.; Yang, J.B.; Gitzendanner, M.A.; Fritsch, P.W.; Cai, J.; Luo, Y.; et al. Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the Jurassic gap. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.J.; Ma, H. Nuclear phylogenomics of angiosperms and insights into their relationships and evolution. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 546–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, L.X.; Hedges, S.B.; Zhong, B.J. New insights on angiosperm crown age based on Bayesian node dating and skyline fossilized birth-death approaches. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.H.; Grimaldi, D.A.; Harlow, G.E.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, M.C.; Lei, W.Y.; Li, Q.L.; Li, X.H. Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U–Pb dating of zircons. Cretac. Res. 2012, 37, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, R.D.; Ko, K. Geology of an amber locality in the Hukawng Valley, northern Myanmar. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2003, 21, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.A.; Eisenstein, D.; Voet, H.; Gazit, S. Female ‘Mauritius’ litchi flowers are not fully mature at anthesis. J. Hortic. Sci. 1997, 72, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, P.K. Disentangling confusions in inflorescence morphology: Patterns and diversity of reproductive shoot ramification in angiosperms. J. Syst. Evol. 2010, 48, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrein, S.; Prenner, G. Unequal twins? Inflorescence evolution in the twinflower tribe Linnaeeae (Caprifoliaceae s.l.). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 174, 200–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A. Pair-flowered cymes in the Lamiales: Structure, distribution and origin. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, J. Comparative anatomy and morphology of flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae. I. Some Australian taxa. Phytomorphology 1959, 9, 325–358. [Google Scholar]

- Haber, J. Comparative anatomy and morphology of flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae. II. Some American taxa. Phytomorphology 1961, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.A.S.; Briggs, B.G. Evolution in the Proteaceae. Aust. J. Bot. 1963, 11, 21–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.W.; Tucker, S.C. Inflorescence ontogeny and floral organogenesis in Grevilleoideae (Proteaceae), with emphasis on the nature of the flower pairs. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1996, 157, 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, P.K.; Igersheim, A. Gynoecium structure and evolution in basal angiosperms. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2000, 161, S211–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igersheim, A.; Endress, P.K. Gynoecium diversity and systematics of the Magnoliales and winteroids. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1997, 124, 213–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronse De Craene, L.P.; Quandt, D.; Wanntorp, L. Floral development of Sabia (Sabiaceae): Evidence for the derivation of pentamery from a trimerous ancestry. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, E.M.; Crane, P.R.; Pedersen, K.R. The Early Flowers and Angiosperm Evolution; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 1–596. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch, E.; Mai, D.H. Monographie der Früchte und Samen in der Kreide von Mitteleuropa; Ustredniho Ustavu Geologickeho: Praha, Czech Republic, 1986; Volume 47, pp. 1–219. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, D.E.; Senters, A.E.; Zanis, M.J.; Kim, S.; Thompson, J.D.; Soltis, P.S.; Ronse De Craene, L.P.; Endress, P.K.; Farris, J.S. Gunnerales are sister to other core eudicots: Implications for the evolution of pentamery. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronse De Craene, L.P. Meristic changes in flowering plants: How flowers play with numbers. Flora 2016, 221, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubitzki, K. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume IX Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p.p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p.p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 418–435. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume VI Flowering Plants. Eudicots. Dicotyledons: Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 202–215, 239–254, 320–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume X Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Sapindales, Cucurbitales, Myrtaceae; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 212–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kubitzki, K.; Bayer, C. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume V Flowering Plants. Eudicots. Dicotyledons: Malvales, Capparales and Nonbetalain Caryophyllales; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, J.W.; Jeffrey, C. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume VIII Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Asterales; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 7–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, J.W.; Bittrich, V. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume XV Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Apiales, Gentianales (Except Rubiaceae); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 413–556. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, J.W.; Bittrich, V. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume XIV Flowering Plants. Eudicots: Aquifoliales, Boraginales, Bruniales, Dipsacales, Escalloniales, Garryales, Paracryphiales, Solanales (Except Convolvulaceae), Icacinaceae, Metteniusaceae, Vahliaceae; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 17–401. [Google Scholar]

| Sepal Number | Petal Number | Stamen Number | Stamen Opposite to Petals? | Anther Attachment | Existence of Disk | Style | Ovary Position | Carpel Number | Placentation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. pilosa | at least 3 | 5, free | at least 4 | yes or no | dorsifixed | no | 2-lobed | semi-inferior | 3 | unknown |

| Saxifragaceae | (3−) 5 (−10) | (4) 5 (6) | 5/5 + 5 | no | basifixed | no | 2–3 divided | superior to inferior | 2–3 | axile or parietal |

| Rhamnaceae | (3) 4–5 (6) | (3) 4–5 (6) | 4–5 | yes | anther minute | yes | 2–4-lobed | superior to inferior | 2–4 | basal |

| Myrtaceae | 4–5 | 4–5 | numerous | / | dorsifixed | yes | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 1–5 | parietal, axile or basal |

| Ancistrocladaceae | 5 | 5 | 10 (5, 15) | / | basifixed | no | 3 (4)-lobed | half-inferior | 3 (4) | pendulous |

| Hydrangeaceae | 4–12 | 4–12, connate | 4—numerous | / | basifixed | no | 1–12 divided | half inferior to inferior | 2–12 | axile at the base and parietal above |

| Loasaceae | (4−) 5 (−8), connate | (4−) 5 (−8), connate | numerous | / | basifixed | no | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 3–5 | parietal |

| Alseuosmiaceae | 4–5 (6), connate | 4–5 (6), connate | 4–5 (6), connate | no | dorsifixed | yes | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 2–3 | axile |

| Argophyllaceae | 5, connate | 5, connate | 5 | no | basifixed | yes or no | solitary | half inferior to inferior | 1–3 | axile |

| Campanulaceae | (3−) 5 (−10), connate | (3−) 5 (−10), connate | (3−) 5 (−10) | yes | basifixed | yes | 2–3-lobed | inferior, rarely half inferior or superior | 2–5 (−10) | axile |

| Araliaceae | (3−) 5 (−12), connate | (3−) 5 (−12) | 3— numerous | / | dorsifixed | yes | 1–numerous | inferior, rarely half inferior or superior | 2–5 (–numerous) | apical |

| Torricelliaceae | (3−) 5, connate | 5 | 5 | no | basi or dorsifixed | yes or no | 3 divided | inferior | 3 | apical or axile |

| Caprifoliaceae s.l. | 4–5 (6), connate | 4–5 (6), connate | 4–5 | no | dorsifixed | yes or no | solitary or 2–3-lobed | inferior | 3 (2–5) | axile or pendulous |

| Viburnaceae | 2–5, connate | 3–5 (6), conate | 3–5 (6) | no | basi or dorsifixed | yes or no | solitary or 2–5-lobed | half inferior to inferior | 2–5 | axile or parietal |

| Actinocalyx bohrii(Ericaceae) | 5, free | 5, connate | 5 | no | basifixed | no | solitary | superior | 3 | central |

| Paradinandra suecica (Ericaceae) | 5, free | 5, connate | 10 + 5 | no | basifixed | no | 3 | superior | 3 | parietal |

| Discoclethra valvata(Clethraceae) | 5, free/connate | ? | ? | ? | ? | yes | 3 | superior | 3 | axile |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Huang, W.; Wang, X. Paired Flowers of Core Eudicots Discovered from Mid-Cretaceous Myanmar Amber. Taxonomy 2025, 5, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy5040067

Li F, Huang W, Wang X. Paired Flowers of Core Eudicots Discovered from Mid-Cretaceous Myanmar Amber. Taxonomy. 2025; 5(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy5040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fengyan, Weijia Huang, and Xin Wang. 2025. "Paired Flowers of Core Eudicots Discovered from Mid-Cretaceous Myanmar Amber" Taxonomy 5, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy5040067

APA StyleLi, F., Huang, W., & Wang, X. (2025). Paired Flowers of Core Eudicots Discovered from Mid-Cretaceous Myanmar Amber. Taxonomy, 5(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/taxonomy5040067