1. Introduction

Protein-based edible films have emerged as promising alternatives for food packaging to petroleum-derived plastics because of their biodegradability, film-forming ability, and favorable mechanical and barrier properties [

1,

2]. To further enhance these functionalities, blending different biopolymers has become a common strategy [

3]. Among the various combinations, protein–protein blends such as gelatin and zein are particularly appealing because they offer complementary physicochemical characteristics. However, when polymers with contrasting hydrophilicity are combined, phase separation frequently occurs. This phenomenon substantially alters the microstructure of the films and, in turn, influences key functional properties. Although previous studies have attempted to improve miscibility through formulation adjustments [

4] or processing modifications [

5], the broader impact of phase separation on overall film performance remains insufficiently clarified.

Phase separation is especially critical in hydrophilic–hydrophobic systems because it can modify water resistance, mechanical strength, barrier performance, heat-sealing behavior, and optical clarity—properties that are central to packaging applications [

6,

7]. While some studies have taken advantage of phase-separated morphologies for specific applications such as encapsulation or controlled release [

8], systematic evaluations of how such structural heterogeneity affects key packaging-related properties are still lacking. This gap is essential because packaging effectiveness depends on the simultaneous optimization of several interrelated parameters rather than on any single property.

Gelatin and zein together provide an ideal model system for studying these effects. Gelatin provides excellent transparency and oxygen barrier ability but suffers from poor water resistance [

9,

10]. In contrast, zein is hydrophobic and water-resistant but forms brittle and visibly colored films [

11,

12]. Their combination offers potential for balanced properties, but also introduces pronounced phase separation due to their contrasting polarities. Understanding how this structural incompatibility governs film functionality is essential for designing effective biodegradable packaging materials.

Because packaging performance depends on multiple interrelated parameters—mechanical strength, heat-sealing behavior, water resistance, barrier performance, and optical properties—assessing only one or two properties can lead to misleading conclusions [

13]. To address this complexity, the present study incorporates a Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) approach that combines the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) with the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [

14,

15,

16,

17]. This framework enables systematic weighting of performance indicators and integrates diverse datasets into a single, comprehensive evaluation.

Therefore, this work aims to (i) clarify how phase separation in gelatin/zein films influences their structural and functional performance across multiple criteria, and (ii) apply an AHP–TOPSIS decision model to identify formulations that achieve the best overall balance for food-packaging applications. By linking phase-separation behavior with holistic performance evaluation, the study provides both fundamental insight and practical guidance for the rational design of sustainable packaging films.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The materials used in this study included zein (reagent grade), gelatin (guaranteed reagent grade), glycerol (type B from bovine skin, guaranteed reagent grade), Mg(NO3)2·6H2O (reagent grade), NaCl (guaranteed reagent grade), and FeSO4·7H2O (reagent grade) were obtained from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). Milli-Q pure water was used throughout the experiments to ensure the highest purity and consistency.

2.2. Film Preparation

Gelatin/zein films were prepared by solution casting using six blend ratios (100:0, 80:20, 60:40, 40:60, 20:80, and 0:100), maintaining a fixed total solid (protein) concentration of 10% (

w/

v). These 20% intervals were selected to span the entire formulation range and enable systematic observation of phase-separation behavior across the hydrophilic–hydrophobic transition while maintaining manageable sample numbers. Gelatin and zein were individually dissolved in 60% (

v/

v) acetic acid at 40 °C for 1 h, following established protocols that ensure efficient solubilization and maintain the gelatin hydrated [

7]. After complete dissolution, the solutions were combined to obtain a film-forming solution (FFS), and glycerol (10%

w/

w of total solids) was added to all formulations as a plasticizer.

The FFS was sonicated (40 kHz, 30 min) to remove entrapped air and improve homogeneity. Subsequently, 8 mL of solution was cast into a 90-mm plastic Petri dish and dried at 50 °C for 24 h. The resulting films were conditioned at 53% relative humidity (RH) using a saturated Mg(NO3)2·6H2O solution for at least 48 h to ensure moisture equilibration before characterization. Samples were denoted according to their zein content: Gel (0%), GZ20 (20%), GZ40 (40%), GZ60 (60%), GZ80 (80%), and Zein (100%).

2.3. Structural Characterization

To examine the onset and effects of phase separation, the films were characterized using FTIR, XRD, TGA, and SEM, which provide complementary structural insights. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, Model 6800, Jasco Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode is utilized to detect changes in molecular interactions and hydrogen bonding that reflect compatibility. The spectra were collected using the FTIR spectrometer with 32 scans in the wavenumber range of 4000–500 cm

−1 [

18].

An X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 ADVANCE/TSM, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) was used. The XRD patterns were obtained using Cu-Kα radiation at an accelerated voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. The samples were scanned over a 2θ range of 5–60°, with an incremental step size of 0.02°. The crystallinity index (CI) was determined using previously reported methods to obtain a semiquantitative measure of the amount of ordered regions and possible new structural arrangements [

8,

19].

Thermal stability was assessed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a simultaneous thermal analyzer (TG/DTA7300, Seiko Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The films were heated from room temperature (23 °C) to 500 °C at a constant rate of 10 °C/min under a high-purity argon (Ar) atmosphere at a flow rate of 200 mL/min.

The surface and cross-sectional morphologies of the film were observed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Hitachi SU-8020, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 1.0 kV. The films were cryo-fractured in liquid nitrogen and sputtered with platinum prior to cross-sectional observation [

20].

2.4. Mechanical Strength

Mechanical strength is crucial for food-packaging films because it determines their ability to withstand handling, transport, and storage without tearing or breaking. The tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EAB) were determined using an electronic tensile test machine (USM-500N, A&D Company, Tokyo, Japan) according to ASTM D882 [

21]. The film strips (70 mm × 10 mm) were fixed on the machine clamps with an additional layer of sandpaper to prevent slippage. The initial clamp distance was set at 50 mm, and the loading speed was 10 mm/min.

2.5. Heat-Sealing Ability

Heat-sealing performance is vital for food-packaging films because it ensures package integrity and prevents leakage or contamination during storage and handling. Heat-sealing strength was measured according to the method described previously by Liu et al. and Zhao et al. [

18,

22]. The film was cut into strips with dimensions of 35 mm × 15 mm, and two strips overlapped each other (

Figure S1a). An area of 5 mm × 15 mm near the edge was heat sealed using an impulse sealer machine (MB 5 × 300SA, As One Cop., Tokyo, Japan) at 100 °C and 0.2 MPa for 3.5 s. The heat-sealed film strips were fixed on the tensile test machine with an initial distance of 40 mm. The test speed was maintained at 20 mm/min. Failure mode is described in ASTM F-088 [

23], as shown in

Figure S1b. Heat seal strength was calculated using the following Equation (1):

where

Pmax (N) is the maximum load recorded on the machine and w (m) is the width of the sealed film.

2.6. Water Resistance

Water resistance is critical for food-packaging films because it helps prevent moisture penetration, structural deterioration, and product quality loss. In this study, water resistance was assessed using water contact angle (WCA), which reflects surface hydrophobicity, and water solubility (WS), which indicates the film’s bulk resistance to water exposure.

2.6.1. Water Contact Angle

The water contact angle (WCA) was measured using an automatic contact angle meter (DropMaster DMs-401, Kyowa Interface Science Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan). Film samples were cut into 10 × 10 mm squares and placed on the stage; after that, a 1 µL droplet of Milli-Q water was deposited onto the surface [

5]. The WCA was recorded using the θ/2 method at 0, 30, and 60 s.

2.6.2. Water Solubility

Water solubility (WS) of the films was conducted according to the method described by Kanmani and Lim, Kurt et al., and Liu et al. [

22,

24,

25]. Briefly, films were cut into 50 mm × 10 mm and weighed (±0.0001 g) after drying at 105 °C to obtain a constant weight (

W0). The dried film strips were then immersed in distilled water, followed by stirring constantly at 50 rpm at 25 °C for 24 h. The undissolved portion was separated by filtration and dried at 105 °C to obtain the final weight (

W1). The WS was calculated using the following Equation (2):

2.7. Gas Barrier Properties

Gas barrier performance is essential for food-packaging films because it helps prevent oxygen infiltration and moisture transfer, both of which can accelerate spoilage (microbial attack) and reduce product shelf life (oxidation). In this study, gas-barrier properties were evaluated through oxygen permeability, which reflects resistance to oxygen diffusion, and water vapor permeability, which indicates the film’s ability to limit moisture transmission.

2.7.1. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

WVP was determined following the procedure of Yang et al. and ASTM E96 (desiccant method), with minor modifications [

26,

27]. Briefly, weighing glass bottles with a diameter of 15 mm and a height of 125 mm were filled with 10 g of anhydrous silica gel. 30 mm × 30 mm film pieces were placed at the mouth of the weighing bottles and sealed. The weighing bottles were placed in a desiccator conditioned by distilled water to obtain an approximate. 100% RH at a 23 °C environment. The increased weight of the weighing bottle is considered to be the amount of absorbed moisture. The weight of the weighing bottle was measured every 24 h for 3 days. The WVP was calculated using the following Equation (3):

where ∆

m (g) is the increased weight of the weighing bottle,

x (cm) is the film thickness measured using a digital thickness gauge (TW-21, Tozai Seiki, Tokyo, Japan) with a precision of 1 µm, and

S (cm

2) is the permeation area of the film.

t (s) is the time interval, and ∆

P is the partial vapor pressure, which is 2339 Pa at 20 °C.

2.7.2. Oxygen Permeability (OP)

OP was measured based on the existing method by Zhao et al. with a slight modification [

18]. Briefly, similar to the WVP testing, the films were cut into 30 mm × 30 mm pieces and placed at the mouth of the weighing bottles filled with 10 g iron sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO

4·7H

2O). The weighing bottles were put into a desiccator containing saturated NaCl solution to maintain an RH of 75% in a 23 °C environment. The weight of the weighing bottle was recorded at intervals of 24 h for 3 days, and the increased weight was determined as the oxygen mass absorbed by FeSO

4.7H

2O. The OP was calculated using the following Equation (4):

where ∆

m (g) is the increased weight of the weighing bottle,

x (cm) is the film thickness,

S (cm

2) is the permeation area of the film, and

t (s) is the time interval.

2.8. Optical Properties

Optical properties are important for food-packaging films because they influence product visibility, consumer appeal, and protection against light-induced deterioration. Transparency and color were used to assess visual quality, while UV-blocking capacity reflected the film’s ability to shield food from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

2.8.1. Transparency

Film transparency was evaluated by measuring light absorbance at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (ASUV-1100, AS ONE Corporation, Osaka, Japan) [

28]. The films were cut into strips (10 mm × 30 mm) and positioned on the inner side (nearer to the light source) of a quartz cuvette, with air serving as the reference. Transparency was then calculated from the transmittance values according to Equation (5), providing a quantitative assessment of film transparency.

where

x is the average thickness (mm) of the film.

2.8.2. Color

The color of the films was tested by [

29], measuring the CIELAB color parameters (

L*,

b*,

a*) using a digital spectrophotometer (PF7000, Nippon Denshoku Industries Co.Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). A white standard white plate (

Lstd* = 97.71,

astd* = −0.14,

bstd* = 0.13) was used to calculate the total color difference (∆E) using the following Equation (6):

The yellowness index (YI) was calculated using the following Equation (7):

2.8.3. Ultra Violet (UV) Blocking Ability

The UV blocking ability was evaluated using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (3100 PC, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). The films were cut into 10 mm × 30 mm pieces and placed on the inner side (nearer to the light source) of the cuvette. UV–Vis transmittance was recorded at a wavelength range from 200–800 nm. UV blocking performance was evaluated via the transmittance at the UV range of 400–200 nm. In addition, the UV blocking ability was calculated using the following Equation (8) [

30,

31].

where

Tuv represents the average transmittance between UV rays wavelengths 400–200 nm,

Tλ is the sum of the transmittance between wavelengths, and ∆

λ is the number of wavelengths measured to calculate the average transmittance.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted using three independently prepared film batches (n = 3), and each property was measured in triplicate for each batch. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The normality of data distribution and the homogeneity of variances were verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS 28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and significant differences between formulations were determined using the least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test at p < 0.05. Error bars in all figures represent SD, and different small letters in figures and tables indicate statistically significant differences among samples (p < 0.05). Graphs were prepared using OriginPro 2017.

2.10. Comprehensive Evaluation Through MCDM

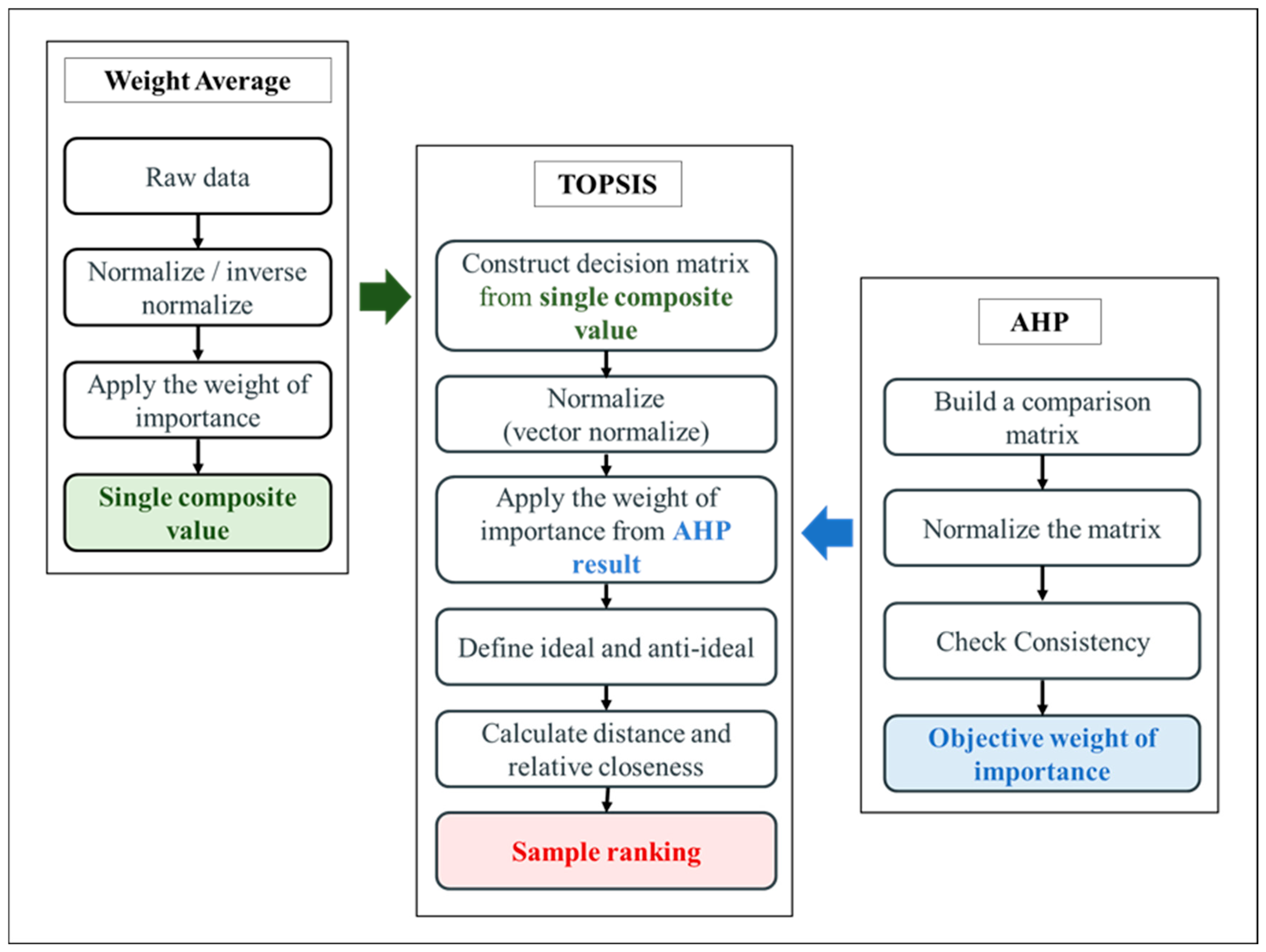

In this study, weights were assigned to each criterion based on domain knowledge and literature review, reflecting the relative importance of mechanical strength, heat-sealing strength, water resistance, gas barrier ability, and optical properties. Mechanical, gas barrier, and optical properties were given higher weights due to their direct impact on packaging performance, while heat-sealing and water resistance were considered secondary. The schematic steps for film performance evaluation using the AHP-TOPSIS approach are displayed in

Figure 1.

In the first step, the weight average is applied to ensure a reasonable and systematic evaluation in the MCDM analysis. Characterization results (sub-criteria) were grouped into representative categories (main criteria) as presented in

Table 1. Then a single composite value was calculated for each main criterion by averaging the relevant sub-criteria. This step was necessary to reduce the total number of criteria, thereby simplifying the subsequent weighting process. In the second step, the AHP was applied to determine the relative importance of each main criterion [

32]. This method provides objective weights while ensuring that the distribution of importance remains logical and consistent. In the final step, the TOPSIS was employed to integrate the weighted criteria values and generate a ranking of the film samples [

33]. This ranking allowed the identification of the most suitable film formulation for food packaging applications.

3. Results and Discussion

The miscibility of gelatin/zein blends is limited by both thermodynamic and kinetic factors. Gelatin, which is rich in polar amino acids, adopts β-sheet/random coil conformations that expose –NH2, –OH, and –COOH groups conducive to hydrogen bonding. In contrast, zein is dominated by nonpolar groups and forms compact α-helices with outward-facing hydrophobic side chains, thereby restricting intermolecular interactions. This structural disparity and polarity mismatch reduce blend miscibility and interfacial adhesion, leading to phase separation. Additionally, the two proteins exhibit distinct solubility and dispersion behaviors in acetic acid, which can lead to asynchronous precipitation and aggregation as the solvent evaporates. This sequential solidification promotes uncoordinated network formation and reinforces the formation of discrete gelatin- and zein-rich domains. Together, molecular incompatibility and non-equilibrium film formation govern the phase behavior of the blend films. These fundamental differences underpin the structural, thermal, mechanical, and other properties observed in the following sections.

3.1. Phase Separation Evidence

3.1.1. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

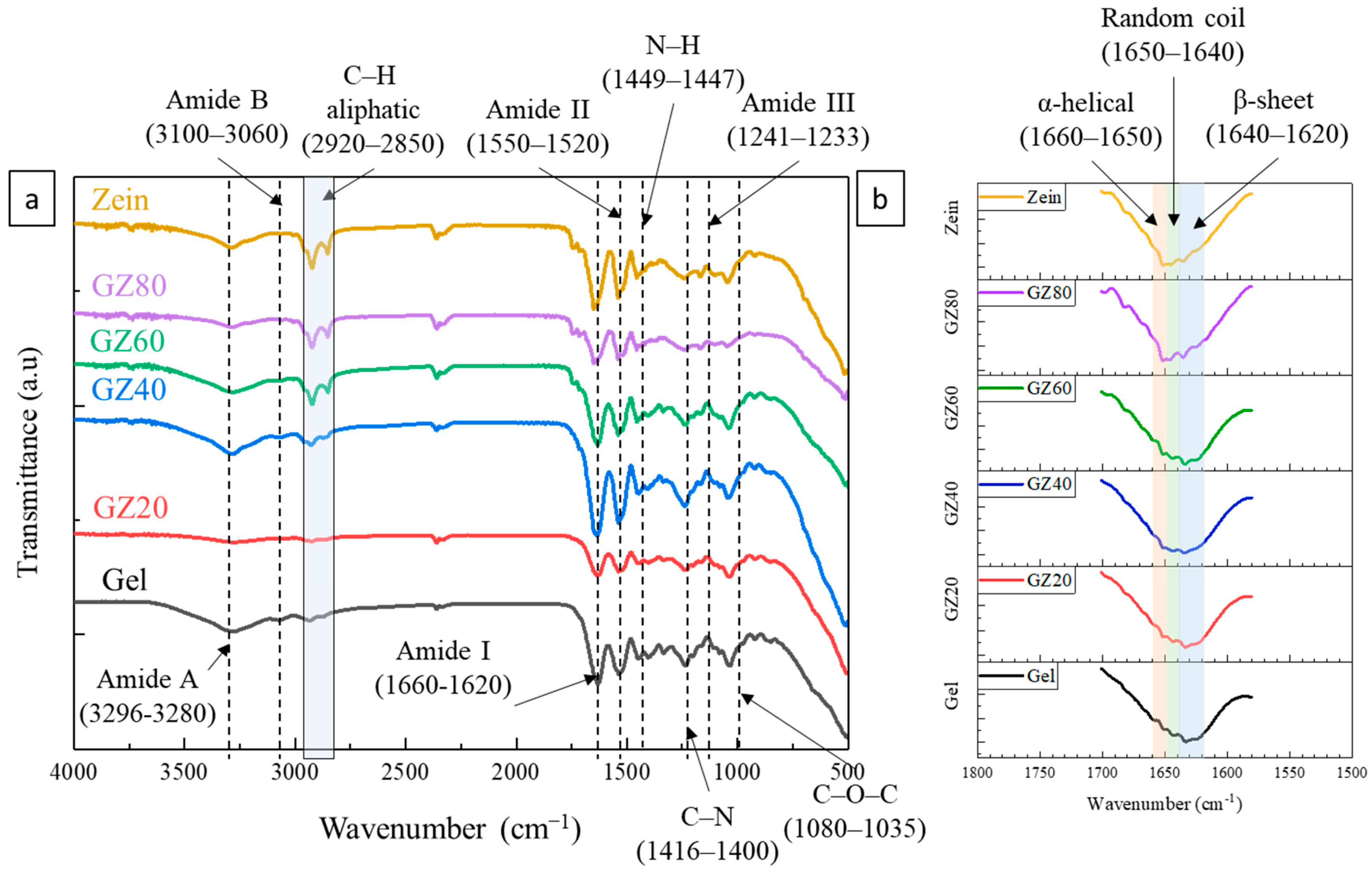

The FTIR spectra of the gelatin/zein films shown in

Figure 2a display the characteristic bands of protein-based materials, dominated by broad and partially overlapping amide absorptions. Although only qualitative interpretation is possible, the spectra still offer valuable insight into changes in hydrogen-bonding environments within the blends and into secondary-structure features derived from amide I analysis.

In the Amide A region (3296–3280 cm

−1), corresponding to N–H stretching of amide groups, all samples display broad bands characteristic of hydrogen-bonded protein matrices. Slight differences in band width and intensity, particularly in GZ40 and GZ60, indicate modest alterations in the hydrogen-bonding environment. These changes likely arose from gelatin–zein interactions and the presence of glycerol, whose O–H groups can form additional hydrogen bonds. The aliphatic C–H bands (≈2920–2850 cm

−1) become more pronounced in zein-rich films (GZ60 and GZ80), consistent with the higher abundance of nonpolar residues such as leucine and alanine in zein [

34].

The Amide I band (1660–1620 cm

−1), primarily attributed to C=O stretching of the peptide backbone, also exhibited compositional shifts and intensity variations. Although detailed secondary-structure interpretation is limited due to band overlap, the spectra in

Figure 2b show the expected contributions: α-helical features at 1660–1650 cm

−1, β-sheet structures at 1640–1620 cm

−1, and random coils at 1650–1640 cm

−1 [

7,

35]. Deconvolution of the amide I region (

Figure S2) enabled a semiquantitative assessment of the secondary structures in the gelatin/zein films [

36]. Gelatin displayed a higher β-sheet content, whereas zein was dominated by α-helical structures. With increasing zein content, α-helix intensity rose, and β-sheet contribution declined, indicating a gradual shift toward zein-like conformations with limited molecular rearrangement. Random coil levels remained nearly unchanged, suggesting that overall conformational disorder was unaffected by blending. The slight up and down of α-helical and β-sheet at GZ60 likely corresponds to local gelatin-rich domains, consistent with partial miscibility and phase separation.

The Amide B band (3100–3060 cm−1), associated with free N–H groups and the amide II and III regions (1550–1520 cm−1 and 1241–1233 cm−1), showed similarly subtle variations in peak profiles with increasing zein content. These slight differences are consistent with limited changes in the C–N and N–H bond environments; however, extensive band overlap prevents precise structural attribution.

Overall, FTIR confirms that both gelatin and zein are present in all formulations and indicates that blending produced modest modifications in the hydrogen-bonding environment. The results, therefore, support only general trends in intermolecular interactions. The amide I curve fitting suggests the view that gelatin and zein were not fully miscible but exhibited partial compatibility, which enabled modest conformational adjustments at their interface.

3.1.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

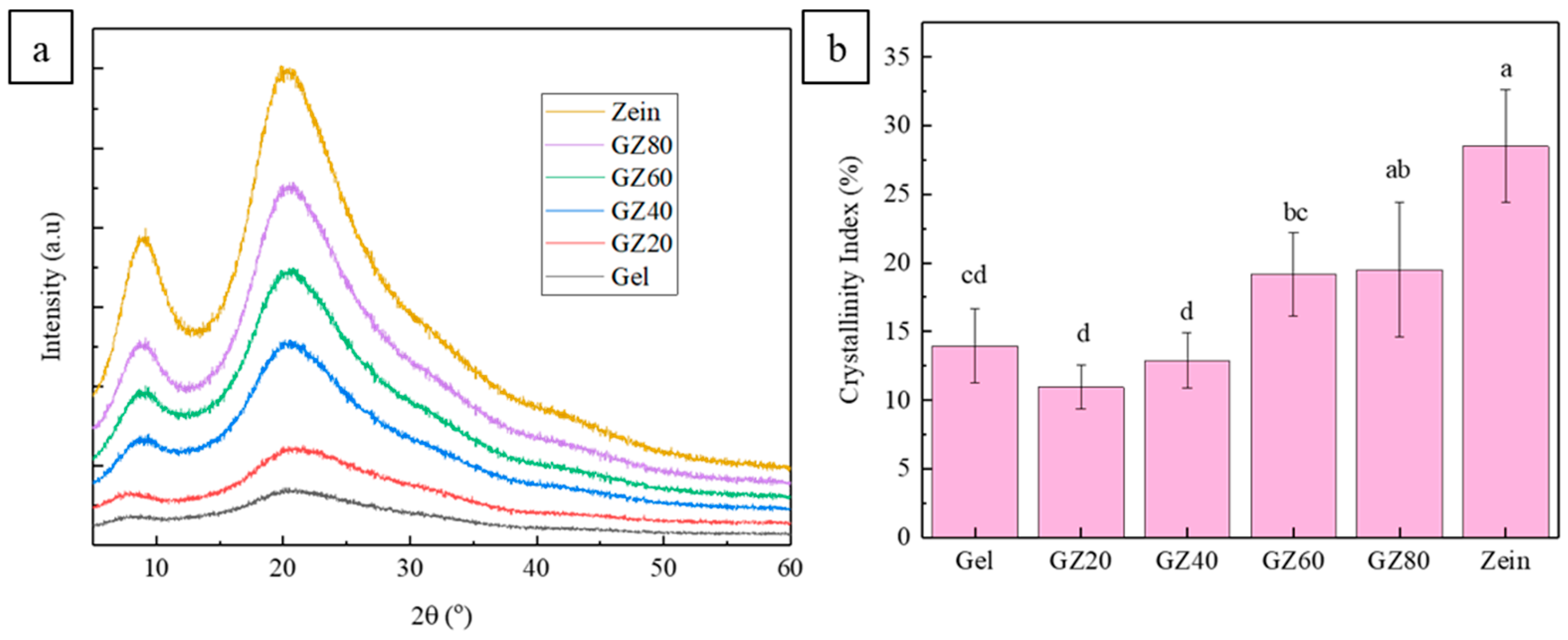

The XRD patterns of gelatin, zein, and their blends (

Figure 3a) were dominated by broad halos centered around 19.9–21.8°, which is characteristic of the largely amorphous nature of both proteins [

5,

37,

38]. All formulations displayed a broad, diffuse diffraction feature with minimal variation in peak shape, indicating that blending did not induce significant long-range crystallinity. The slight peak sharpening at higher zein contents likely reflects minor differences in local chain packing rather than true crystalline domain formation. Given the broad and overlapping patterns, these changes should be interpreted cautiously as qualitative indicators of local structural rearrangement.

A weak and broad reflection at 7.9–9.4° appeared in the zein-containing films, corresponding to the short-range α-helical packing in zein. Its slight increase in intensity with higher zein levels reflects the growing presence of zein-rich domains rather than the development of well-defined crystalline structures [

32]. Pure zein displayed a more pronounced signal in this region, whereas pure gelatin showed only a low-intensity diffuse feature, consistent with its largely disordered triple-helix remnants and amorphous backbone.

The crystallinity index (CI) values (

Figure 3b) were low across all samples, as expected for protein-based films. No significant increases in CI were observed at either higher gelatin (compared to gelatin) or higher zein contents, and all values remained below that of neat zein. This indicates that blending did not induce cooperative crystallization or new ordered phases; rather, each protein largely preserved its inherent amorphous structure.

Overall, the XRD results confirm that the films were predominantly amorphous, with only minor composition-dependent variations in short-range order. The CI trends also support the view that the blends exhibited partial immiscibility, as zein neither disrupted gelatin’s structural organization nor promoted a mixed crystalline phase. The XRD results also provide only limited structural insight into the gelatin–zein system, and our conclusions regarding miscibility and interfacial interactions are therefore primarily supported by complementary characterization techniques.

3.1.3. Thermal Properties

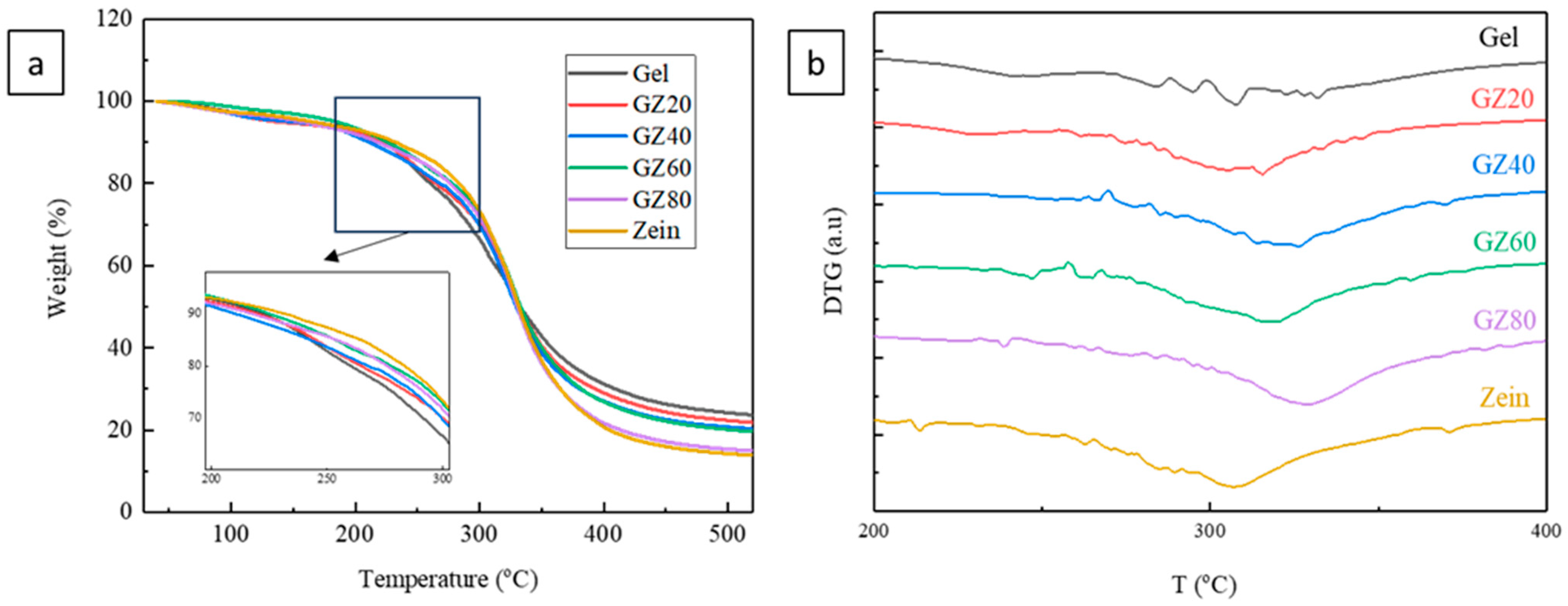

The TGA curves of gelatin, zein, and their blends (

Figure 4a) exhibited the typical three-stage thermal degradation profile characteristic of protein-based films shown in

Table 2. The first mass-loss event, occurring between 79 and 103 °C, accounted for 1.40–3.07% loss and is attributed to the evaporation of residual free and loosely bound water.

The second mass-loss event (245–277 °C), accounting for 16–20% loss, could not be attributed solely to glycerol. Although glycerol was added at 10% relative to protein mass, its effective proportion in the dry film is slightly higher after water removal. More importantly, this temperature region includes the onset of protein degradation, which produces low-molecular-weight volatile fragments that overlap with glycerol volatilization. These volatile products include amino acid side-chain fragments, small organic acids, ammonia, and carbon dioxide, all of which are known to form during the earliest stages of protein thermal decomposition [

39,

40,

41].

In several blend films (GZ40, GZ60, GZ80), the TGA curves showed shoulder-like features and nonlinear slopes, indicating overlapping degradation events from gelatin-rich and zein-rich domains that decompose at slightly different temperatures. This behavior aligns with the partial phase separation suggested by structural analyses, although the evidence remains qualitative due to overlapping transitions typical of protein systems.

The main decomposition stage (308–331 °C) accounted for 31.42–50.45% mass loss and corresponded to extensive protein backbone degradation. The DTG curves (

Figure 4b) further distinguish these stages. Incorporation of zein slightly increased the degradation onset temperature relative to neat gelatin, indicating modest improvements in thermal stability. This enhancement likely reflects interfacial interactions or limited compatibility that restricted chain mobility at the boundaries of gelatin- and zein-rich domains rather than true molecular-level miscibility. Notably, pure zein degraded at a lower onset temperature than several zein-rich blend films, suggesting that the presence of gelatin provided stabilized interactions—potentially associated with β-sheet structures—that delayed the thermal decomposition [

42].

Overall, the TGA results demonstrate that gelatin/zein films exhibit predominantly phase-separated thermal behavior, with each protein largely retaining its characteristic degradation pathway. The slight improvements in the thermal stability of zein-rich blends suggest some degree of interfacial adhesion, even though full miscibility is not achieved. These findings support a morphology in which limited compatibility and domain-level interactions influence thermal response without forming new homogeneous thermal phases.

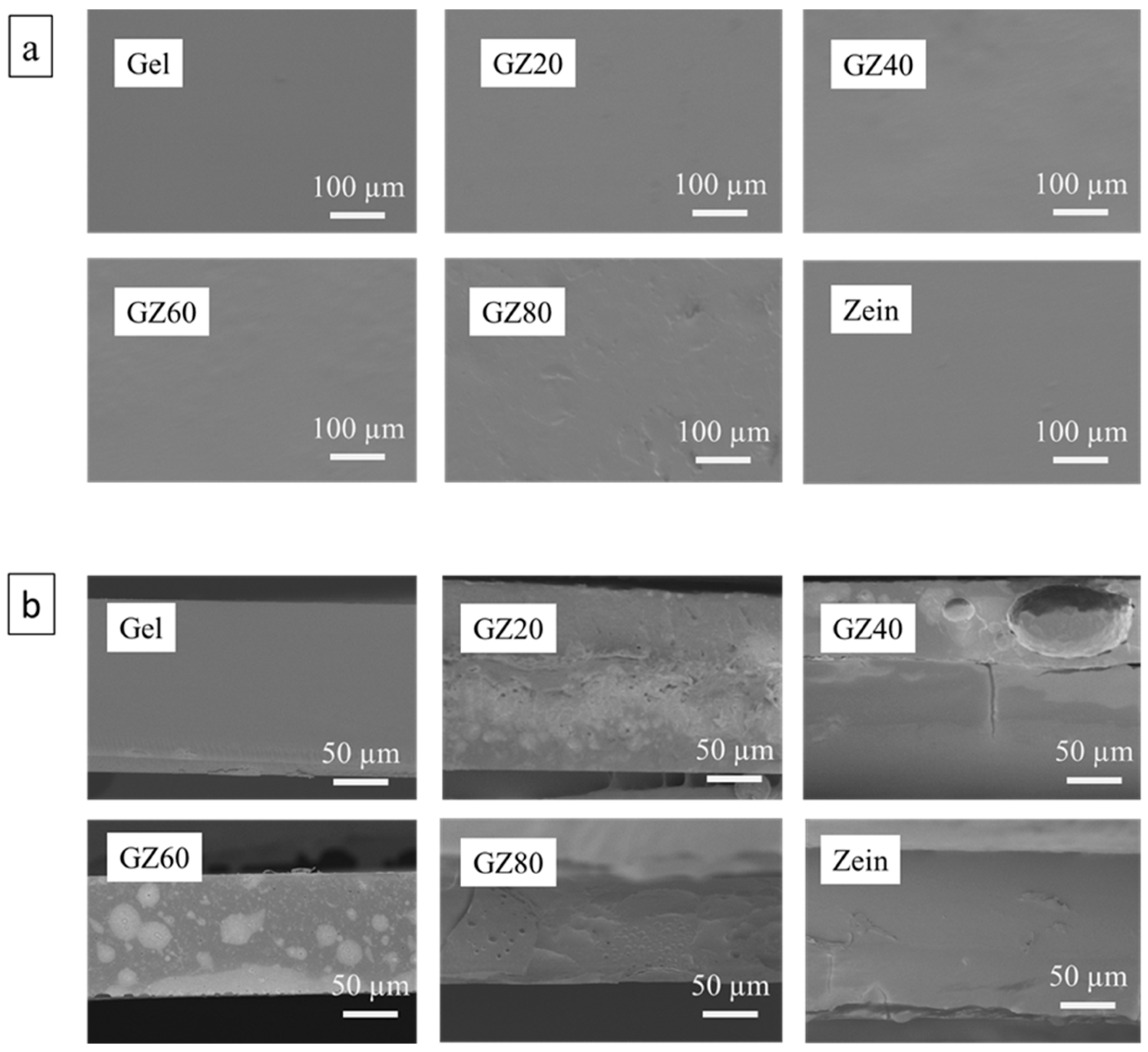

3.1.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

As shown in

Figure 5a, the surface morphology analysis reveals that the gelatin/zein films exhibited a relatively smooth and continuous surface, suggesting that solvent evaporation during solution casting was uniform. Such smoothness implies reduced formation of macroscopic defects such as wrinkles or rough textures, which are often associated with uneven drying. This observation further indicates that the addition of glycerol as a plasticizer, combined with the applied drying temperature, effectively enhanced chain mobility and prevented film shrinkage or cracking during the drying process [

43]. However, as shown in

Figure 5b, cross-sectional images provide clear evidence of immiscibility between gelatin and zein. Distinct microstructural features such as layering, porosity, voids, as well as granular or droplet-like inclusions, were apparent in GZ20, GZ40, GZ60, and GZ80 films [

44,

45]. These heterogeneous structures strongly suggest phase separation rather than the formation of a fully homogeneous blend. Overall, these results demonstrate that while the film surface appeared macroscopically uniform, the interior microstructure remains heterogeneous due to the limited miscibility of gelatin and zein. This discrepancy highlights the critical role of phase separation in governing the structural organization of gelatin/zein films.

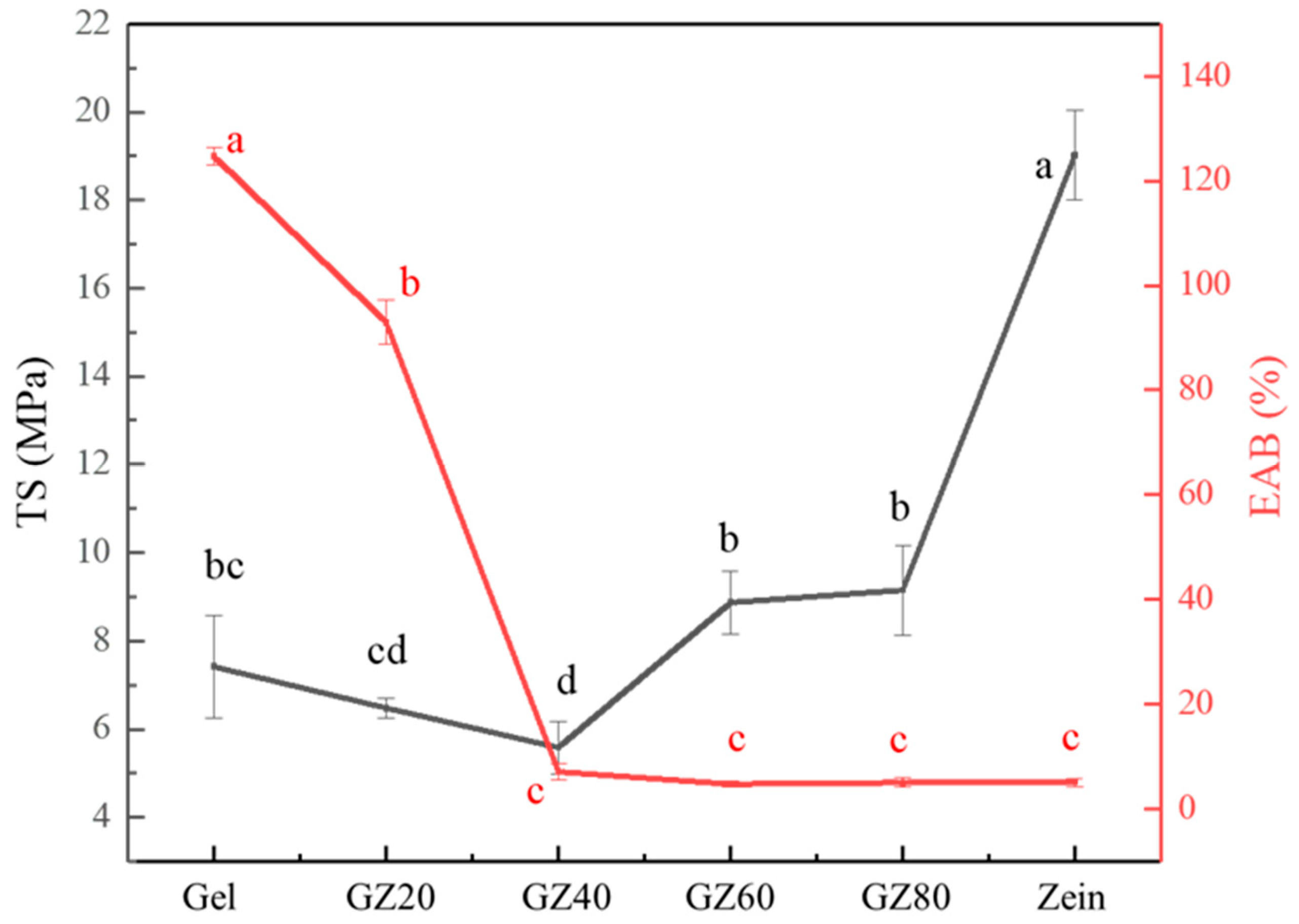

3.2. Phase-Separation Correlation on Mechanical Strength

3.2.1. Tensile Strength and Elongation at Break

As shown in

Figure 6, the incorporation of zein into gelatin markedly influenced the TS and EAB of the films. Pure gelatin film exhibited a TS of 7.2 MPa and a high EAB of 124.71%, consistent with the flexible and hydrated nature of the gelatin network. Upon the addition of 20–40% zein, both TS and EAB decreased, with TS values of 6.47 and 5.58 MPa and EAB values of 92.95% and 7.12% for GZ20 and GZ40 films, respectively. These reductions reflect the formation of a phase-separated structure in which gelatin acts as the continuous matrix while zein forms dispersed domains. In this composition range, the limited compatibility between the two proteins resulted in insufficient stress transfer across the interface, causing the zein domains to behave more like structural discontinuities than reinforcing elements and thereby reducing both strength and ductility.

At higher zein contents (GZ60 and GZ80), TS increased to 8.87 and 9.15 MPa, eventually reaching 19.02 MPa in pure zein film. This trend indicates a matrix inversion, where zein became the continuous phase, and gelatin was dispersed as isolated inclusions. Because zein possesses inherently higher rigidity and strength than gelatin, the shift to a zein-dominated matrix could enhance TS. However, EAB remained low (approximately 5%) in all zein-rich formulations, reflecting the restricted mobility of the α-helical zein structure and the inability of gelatin domains to provide significant ductility in the absence of strong interfacial adhesion.

Although the overall mechanical behavior is consistent with a bi-phase system and limited miscibility, the property trends did not follow a simple rule of mixtures. The relatively smooth transition in TS across compositions and the absence of abrupt mechanical failure suggest that gelatin and zein exhibit some degree of interfacial adhesion, likely arising from weak hydrogen bonding or dipolar interactions at domain boundaries. These interactions permitted partial stress transfer between the two phases, even though the bulk morphology remained phase-separated. This interpretation is supported by the complementary thermal and spectroscopic analyses, which show partial compatibility but no formation of a single homogeneous phase.

Together, the mechanical and morphological results indicate that gelatin/zein films formed a phase-separated structure with limited but non-negligible interfacial compatibility. This influenced load distribution and contributed to the composition-dependent mechanical properties observed, which align with the FTIR, thermal, and morphological data.

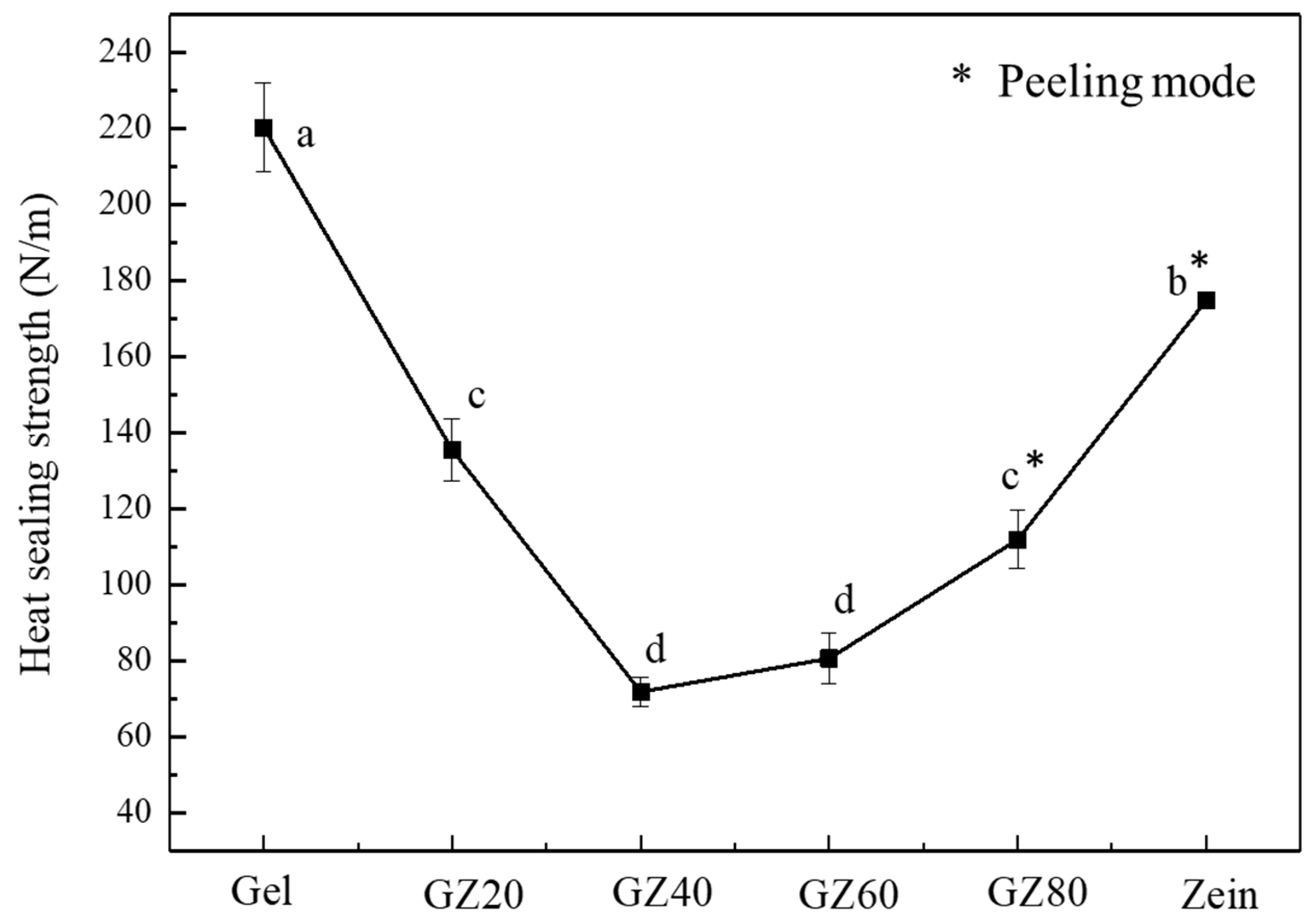

3.2.2. Heat-Sealing Strength

The heat-sealing strength of the films showed a clear dependence on composition (

Figure 7), reflecting differences in surface mobility rather than bulk mechanical behavior. Pure gelatin film exhibited the highest seal strength because residual moisture plasticized the gelatin chains, allowing them to soften and interdiffuse easily within the sealing temperature range (70–100 °C). In contrast, the pure zein film showed lower seal strength because its rigid, hydrophobic α-helical structure restricted chain mobility and reduced effective bonding at the sealing interface. The frequent peeling mode in zein-rich films further indicates poor chain mobility compared with gelatin.

Although gelatin and zein were largely phase-separated in the bulk, the moderate seal strengths observed in intermediate compositions suggest some degree of surface reconstruction and interfacial adhesion occurred during sealing. This explains why the sealing strength gradually decreased with higher zein content rather than dropping abruptly, and why surface behavior did not fully mirror the bulk immiscibility of the two polymers.

These observations indicate that heat-sealing performance was governed primarily by surface chain mobility and surface composition. Gelatin facilitated chain interdiffusion and enabled hydrogen bonding during sealing. These findings agree with the partial interfacial compatibility inferred from the mechanical, FTIR, and thermal analyses, suggesting that surface-level interactions occurred even though the bulk morphology remains phase-separated.

3.3. Phase-Separation Correlation on Water Resistance

3.3.1. Wettability

The incorporation of zein into gelatin produced fluctuating WCA values, as shown in

Table 3, which were strongly influenced by both surface chemistry and topography [

46]. Surface roughness plays a critical role in wettability, as rougher surfaces tend to trap more air pockets and initially increase the WCA according to the Assie–Baxter model. The WCA of all films consistently decreased within 30–60 s after droplet deposition. This decline was primarily attributed to the intrinsic hydrophilicity of gelatin, which facilitated water absorption and penetration into the film matrix. Gelatin-rich regions at the surface were capable of swelling upon hydration, progressively softening the interfacial layer and exposing additional hydrophilic groups. This dynamic process enhanced water spreading and lowered the apparent WCA over time. Similar time-dependent decreases in WCA have also been reported for gelatin/zein blend films fabricated by layer-by-layer assembly and electrospinning [

5,

46,

47]. Additionally, the rearrangement of surface molecule segments in response to water exposure may further contribute to the observed time-dependent wettability.

Although the introduction of zein might be expected to enhance hydrophobicity, the actual WCA results suggest otherwise. The drying process during solution casting has an essential impact on the final surface properties. Gelatin/zein films solidified via a layer-by-layer mechanism initiated at the air–liquid interface, driven by solvent evaporation. This directional solvent removal generated a concentration gradient, leading to preferential orientation of hydrophilic moieties (e.g., –NH

2, –COOH, –OH) toward the air-exposed surface, while hydrophobic residues are enriched in the subsurface region [

46,

48]. In addition, phase separation between gelatin and zein resulted in heterogeneous surface domains composed of hydrophilic gelatin-rich and hydrophobic zein-rich areas. The coexistence of these chemically distinct regions, together with micro- and macro-scale roughness at their boundaries, amplifies wettability fluctuations and accounts for the non-uniform WCA values measured in the blend films.

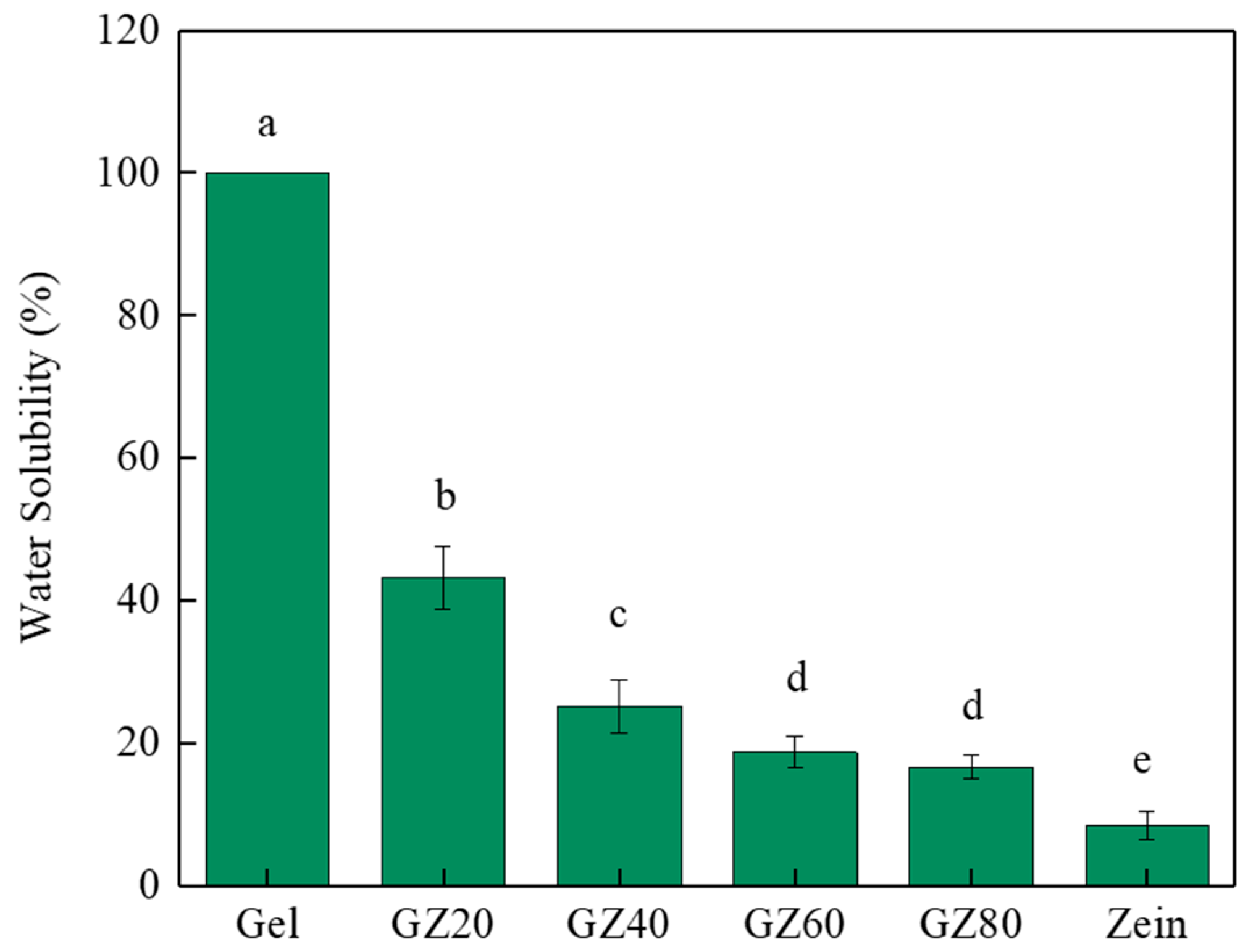

3.3.2. Bulk Water Resistance

WS reflects the structural stability of film in aqueous environments and provides complementary information to WCA. Whereas WCA characterizes the surface wettability, WS evaluates the bulk resistance of the polymer matrix to water penetration and dissolution. A lower WS value thus indicates improved cohesion and water barrier ability [

37]. The incorporation of zein markedly reduced the WS of gelatin/zein films, from nearly complete dissolution in pure gelatin (100%) to 43.2% in GZ20 film, as shown in

Figure 8. Among the blended films, GZ80 film showed the lowest WS of 16.6%, while pure zein exhibited the greatest water resistance with a WS of only 8.4%. This progressive decline confirms that zein significantly enhanced the WS by forming a hydrophobic continuous network that suppresses water diffusion and polymer chain release.

However, the effect of zein incorporation was not entirely linear due to the phase separation between gelatin and zein. As observed in SEM images, heterogeneous domains with poor interfacial compatibility were present in blending films (GZ20–GZ80). These discontinuities disrupted the formation of a fully integrated hydrophobic barrier, leaving water-accessible pathways within the matrix. As a result, the WS of intermediate blends, although lower than pure gelatin, did not decline as drastically as expected when compared to zein-rich systems.

The inherently low WS of zein arose from its high proportion of nonpolar amino acids and the α-helical structures in which hydrophobic side chains were oriented outward while the limited hydrophilic groups were buried inside, thereby limiting hydrogen bonding with water molecules [

12]. This molecular hydrophobicity explains why zein-rich formulations consistently exhibit superior water resistance compared to gelatin-rich counterparts, while phase separation accounts for the less pronounced improvements observed in blending films.

3.4. Phase-Separation Correlation on Gas Barrier Properties

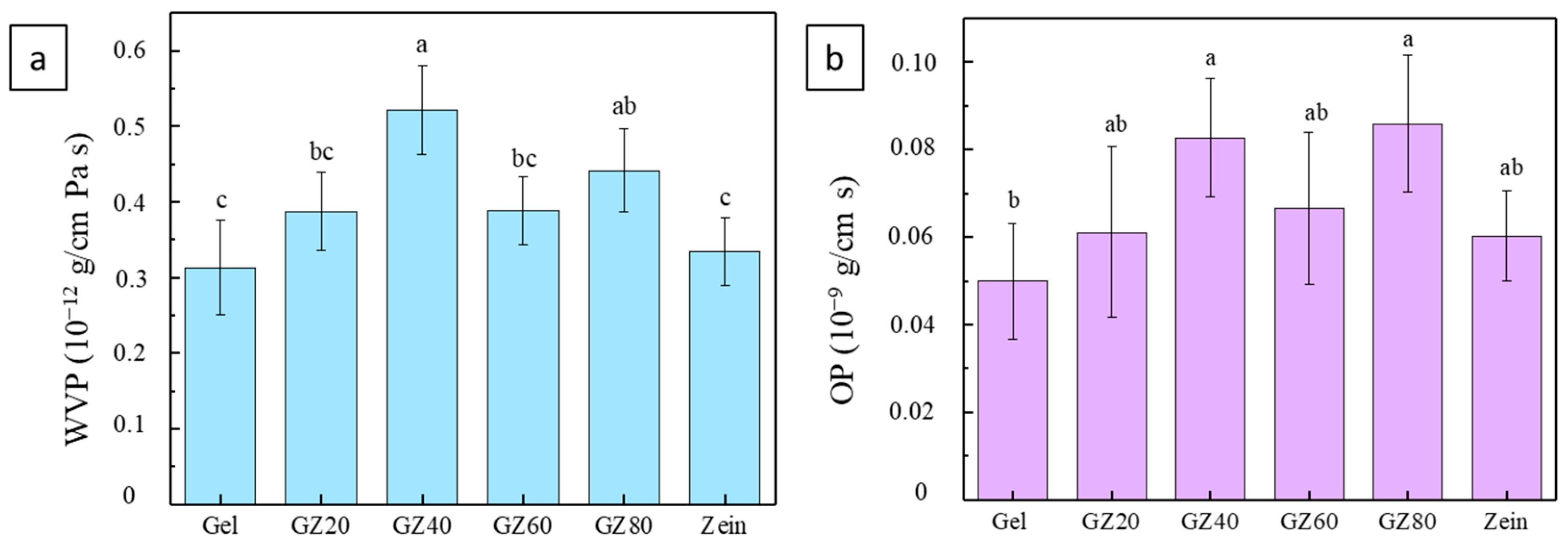

Gas barrier properties are crucial for food packaging because water vapor and oxygen accelerate deterioration. WVP and OP quantify the film’s resistance to polar water molecules and nonpolar oxygen, and both are strongly influenced by phase separation and the hydrophilic–hydrophobic balance of the blend.

As shown in

Figure 9a, WVP displayed a nonlinear trend with zein incorporation. At intermediate zein levels (GZ40 and GZ60), WVP increased due to immiscibility-driven microvoids and interfacial gaps formed during drying, which facilitated moisture diffusion. The reduced cohesion between gelatin and zein also contributed to higher permeability. At higher zein contents (GZ80 and pure zein), WVP decreased as zein formed a more continuous, compact, and hydrophobic phase that limited water vapor transport.

A similar pattern was observed for OP (

Figure 9b). Gelatin-rich films absorbed moisture, which disrupted chain packing and increased oxygen diffusivity. At intermediate blend ratios, phase separation introduced additional diffusion pathways. With higher zein content, the matrix became denser and more hydrophobic, reducing oxygen transmission. Pure zein films exhibited the lowest OP values due to their compact and cohesive structure.

Overall, these results show that phase separation governs barrier performance: intermediate blends are weakened by interfacial defects, whereas zein-rich films benefit from reduced phase separation and the intrinsic hydrophobicity of zein, yielding improved resistance to both water vapor and oxygen.

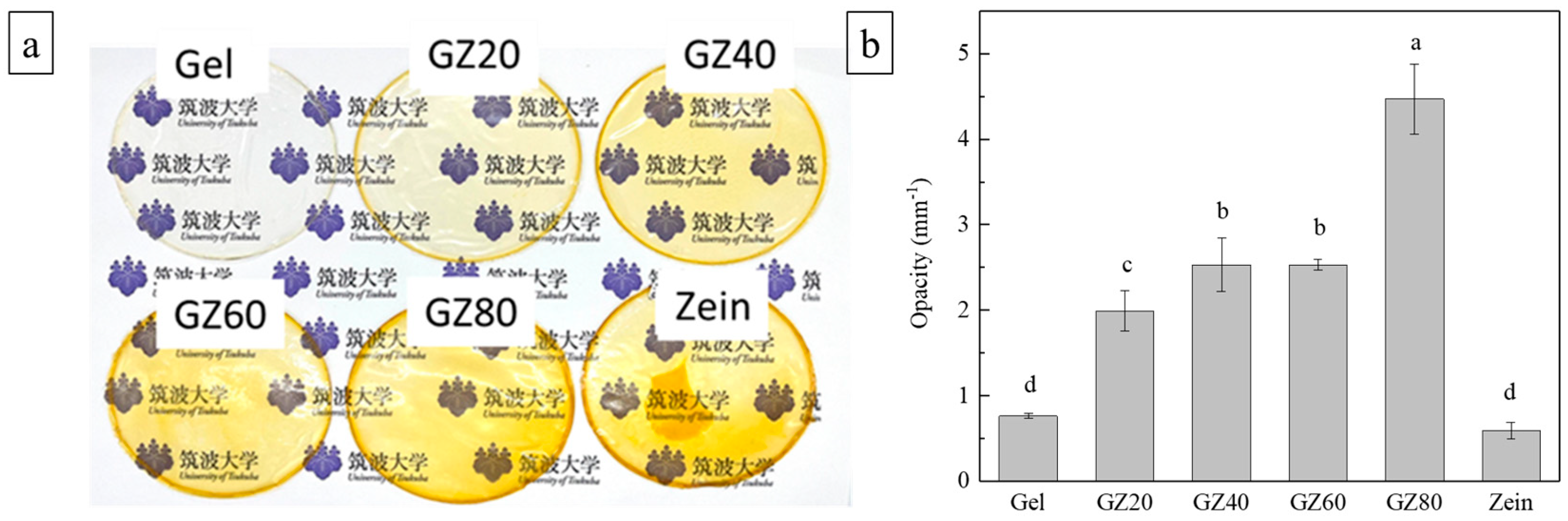

3.5. Phase-Separation Correlation on Optical Properties

3.5.1. Transparency and Color

Optical performance is an important attribute for packaging films because it influences product visibility and consumer perception. As shown in

Figure 10a,b, the incorporation of zein significantly reduced transparency, with blend films exhibiting much higher opacity than pure gelatin or pure zein [

49]. Since both individual components were highly transparent, the decreased transparency in the blends is attributed to phase separation, where the formation of immiscible domains enhances light scattering [

50]. This indicates that incompatibility, rather than intrinsic material properties, governed the loss of transparency. While this may limit applications requiring clarity, increased opacity can be advantageous for protecting light-sensitive foods.

Color measurements (

Table 4) showed that increasing zein content decreased L* (darker films) and increased b* (more yellow), consistent with the presence of natural pigments such as carotenoids and xanthophylls in zein [

51]. Correspondingly, both YI and ΔE rose sharply with higher zein levels. All zein-containing films displayed ΔE > 5, indicating clearly perceptible color differences, and values exceeded 12 in higher-zein films, making the changes visually obvious [

52]. These results confirm that zein incorporation substantially modifies chromatic appearance, which may either enhance visual differentiation or pose a limitation depending on the intended packaging application.

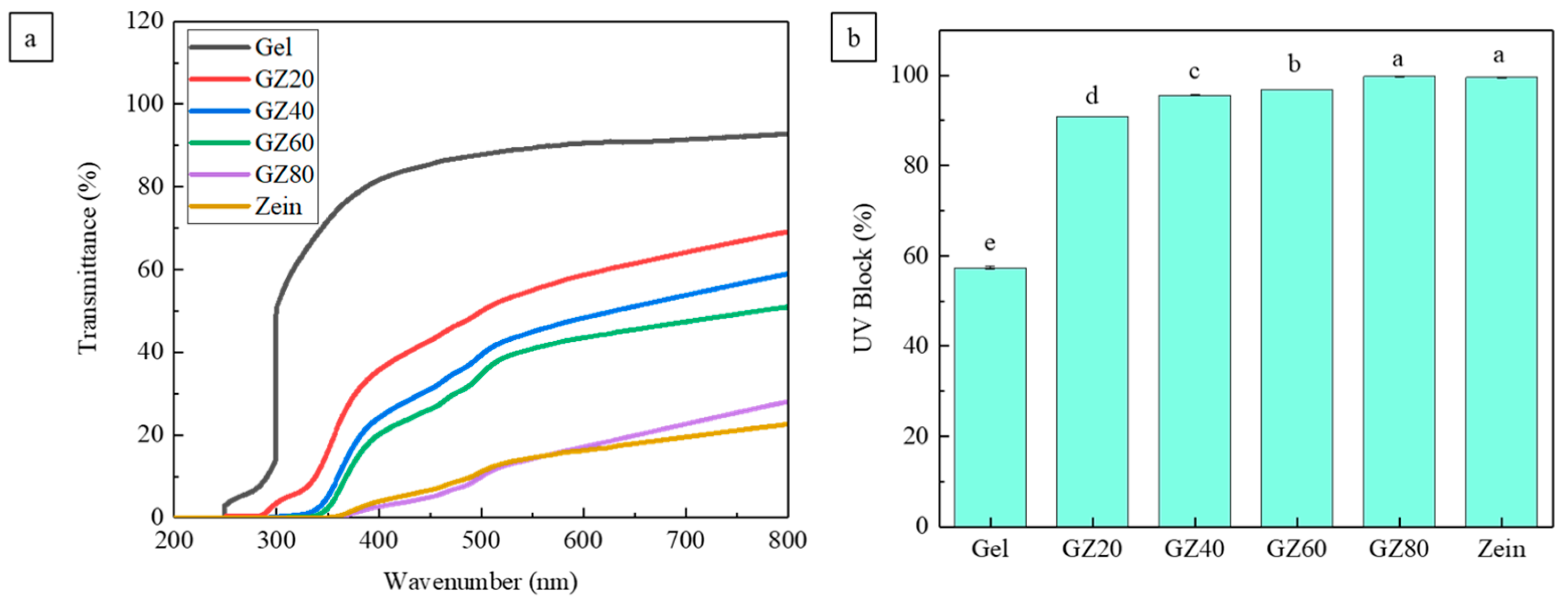

3.5.2. UV Blocking Ability

Food spoilage triggered by UV radiation is largely driven by free-radical formation, which accelerates lipid oxidation, protein degradation, and color loss [

53,

54]. Thus, UV shielding is an important packaging function. As shown in

Figure 11a, incorporation of zein markedly enhanced UV-blocking performance across the UV-C (200–280 nm) and UV-B (280–315 nm) regions, with moderate improvement in UV-A (315–400 nm). Pure gelatin showed blocking only in the UV-C range, while GZ20 displayed partial UV-B and UV-C protection. Increasing zein content progressively strengthened UV shielding, confirming the dominant role of zein.

This enhancement is primarily attributed to zein’s intrinsic chromophore groups—aromatic amino acids and natural pigments such as carotenoids and xanthophylls—which strongly absorb UV light [

55,

56]. The dense packing of zein-rich domains further contributes to this absorptive effect [

5]. As shown in

Figure 11b, the consistent increase in UV blocking with higher zein content indicates that molecular absorption, rather than morphological scattering from phase separation, is the main mechanism. Therefore, improved UV resistance in the gelatin/zein films is chiefly governed by zein’s inherent light-absorbing components.

3.6. MCDM Evaluation

3.6.1. Single Composite Value Through Weighted Average

To evaluate the overall performance of gelatin/zein films, multiple functional properties were selected as main decision-making criteria, including mechanical properties, heat-sealing strength, water resistance, gas barrier performance, and optical properties. These properties are universally regarded as critical for packaging applications, since they collectively determine product protection, stability, consumer safety, and acceptance.

As summarized in

Table S3, each main criterion was evaluated using multiple sub-criteria (e.g., TS and EAB for mechanical properties; WCA and WS for water resistance) to ensure a comprehensive assessment. Because these sub-criteria differ in importance, subjective weights were assigned accordingly—for example, TS was weighted more heavily than EAB due to its greater relevance for packaging integrity, and WS received a higher weight than WCA because it reflects bulk water interaction.

A weighted average method was then applied to generate a single composite score for each criterion. Prior to weighting, all data were normalized using the min–max method to ensure comparability across different units (

Supplementary Materials), with raw values shown in

Table S4. Sub-criteria were treated as benefit or cost indicators depending on whether higher or lower values represented superior performance. This normalization converted all parameters to a 0–1 scale, enabling consistent interpretation and integration into the overall evaluation framework.

The importance weights listed in

Table S3 were then applied using the weighted average formula (Equations (9) and (10)) to combine the normalized values into a single composite value.

where

x represents the normalized (or inverse-normalized) value of each sub-criterion, and

w is its assigned weight of importance. The resulting single composite values, as shown in

Table 5, were subsequently used as input for the TOPSIS step to construct the decision matrix.

3.6.2. Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

In this step, the AHP was employed to determine the relative importance of the main criteria. A pairwise comparison matrix was constructed based on the contribution of each criterion to the essential functions of food packaging, namely protection, stability, product safety, and consumer appeal. Gas barrier properties, optical performance (with emphasis on UV protection), and mechanical properties were prioritized due to their central roles in extending shelf life and maintaining structural integrity. Water resistance and heat-sealing ability were also considered important, but were weighted lower according to their comparatively reduced impact on overall packaging performance.

In AHP, a three-level hierarchy was constructed consisting of the overall goal (optimal film performance), the main evaluation criteria (mechanical properties, heat-sealing ability, water resistance, barrier properties, and optical properties), and the film alternatives, as shown in

Table S6. This structure organizes the decision problem into manageable levels for systematic comparison.

Pairwise comparisons were then performed using the standard 1–9 AHP Saaty’s scale to quantify the relative importance of each criterion (

Table S7). For instance, if mechanical properties were considered twice as important as water resistance, their comparison was assigned a value of 2, with the reciprocal value (0.5) applied in the opposite direction. The resulting comparison matrix was subsequently processed to calculate the final weight coefficients for each criterion. The final weight of importance shown in

Table 6 was obtained after averaging the normalizing value of the matrix and rounding to three decimal places. This process converts many comparisons into a single coherent weight of importance.

To avoid the logical fallacy of subjective judgment, a consistency check was conducted. This step ensured that the importance weights were derived from a coherent system matrix. The original matrix was multiplied by the derived weight vector, resulting in a new matrix. The sum of each row in this resultant matrix is presented in the

Supplementary Materials. Each row sum was divided by the corresponding weights to obtain the eigenvalue of each criterion (

λi). λ

max was 5.23, calculated as the mean of all

λi (

Table S8)

. In a perfectly consistent matrix, all

λi would have identical values. The consistency index (C

i) and consistency ratio (

Cr) can be calculated through the following Equations (11) and (12). The random index (

Ri) shown in Equation (12) was valued as 1.12, according to the Saaty table explained by Donegan et al. (1991) [

57].

The Cr was calculated to be 0.051, below 0.10, indicating satisfactory logical consistency and high reliability. These weights were subsequently used in the TOPSIS analysis to rank the performance of different film formulations.

3.6.3. Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)

The TOPSIS method was applied to evaluate the performance of gelatin/zein films by considering all key packaging-relevant properties simultaneously. This multi-criteria approach integrates diverse attributes into a unified single decision-making framework, thereby overcoming the limitations of assessing individual parameters in isolation.

In this procedure, the single composite values obtained for each property group were first normalized and subsequently multiplied by the criterion weights via the AHP analysis. These weighted normalized values were used to determine the positive (best performance) and negative (worst performance) ideal solutions. For each film formulation, the Euclidean distance to both ideal and negative-ideal solutions was calculated, and the closeness coefficient (C) was derived as an indicator of overall performance, ranging from 0 (worst) to 1 (best).

The results in

Table 7 ranked pure zein as the best-performing film (

C = 0.867), followed by pure gelatin (

C = 0.781) and the GZ20 blend (

C = 0.574). The lowest rankings were observed for GZ60 (

C = 0.361), GZ80 (

C = 0.251), and GZ40 (

C = 0.150). These outcomes highlight that pure films outperformed blended ones when all criteria were integrated, suggesting that blending did not generate a synergistic effect at the holistic level.

Although zein incorporation improved specific attributes such as water resistance, UV-blocking, and tensile strength, and gelatin offered superior heat-sealing ability, the overall performance of the blends was compromised by phase separation. As previously confirmed by FTIR, XRD, and SEM analyses, heterogeneous microstructures with weak interfacial adhesion limited the ability of blends to balance multiple functions simultaneously. This finding provides strong evidence that phase separation tends to improve isolated properties while hindering the comprehensive performance required for practical packaging applications.

4. Conclusions

In this study, FTIR, XRD, TGA, and SEM confirmed heterogeneous phase-separated domains in gelatin–zein films, indicating immiscibility with limited compatibility that strongly affected film behavior. Although zein improved UV blocking, tensile strength, and water resistance, the overall film performance remained inferior to the pure components. This study highlights that incompatibility-driven phase separation can create trade-offs that must be considered in the design of composite biopolymer films. The integration of AHP–TOPSIS with experimental characterization provides a systematic framework for evaluating multi-property trade-offs and for identifying formulations that balance performance criteria more effectively. The holistic evaluation method can provide new insight when optimizing multifunctional packaging materials. As limitations, the absence of compatibilizers, the fixed humidity and drying conditions, and the lack of long-term storage. Furthermore, this work focused on a single protein pair under fixed environmental conditions and did not include real food-packaging trials. Future studies should investigate other biopolymer systems that exhibit phase separation and compare MCDM-derived rankings with actual food-storage performance to further validate the approach as a reliable decision-making tool.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/macromol6010002/s1, Figure S1:(a) Sealed film sample dimension and (b) failure modes (I, II, III, IV) of the seal strength test; Figure S2: Deconvolution of amide I peak of (a) Gel, (b) GZ20, (c) GZ40, (d) GZ60, (e) GZ80, (f) Zein; Table S1: Area of deconvolution peak at amide I peak; Table S2: Relative amount of secondary structure of gelatin/zein film; Table S3: Weight of importance of sub-criteria; Table S4: Raw values of each sample; Table S5: Normalized and inverse-normalized values of each sub-criterion; Table S6: Hierarchical structure of the decision; Table S7: Original matrix of criteria; Table S8: Eigenvalues of each criterion.

Author Contributions

A.Z.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—original draft. P.K.: Methodology, Writing—review and editing. T.E.: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for DC1–PD Fellow (Peifu Kong) (KAKENHI, grant NO. 23KJ0275), and a Grant-in-Aid Printing Technology Research Incentive (Peifu Kong, 2023) from the Japanese Society of Printing Science and Technology. The APC is supported by the operating budget (Toshiharu Enomae) from the University of Tsukuba. The first author’s (Ainun Zulfikar) doctoral studies at the University of Tsukuba, Japan, were made possible by financial support from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) through the Japanese Leader Empowerment Program (JLEP).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| AHP | Analytical Hierarchy Pro |

| DTG | Linear dichroism |

| EAB | Elongation at Break |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| MPa | Mega Pascal |

| OP | Oxygen Permeability |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| RPM | Revolution per minute |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution |

| TS | Tensile Strength |

| UV | Ultra Violet |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet -Visible Spectroscopy |

| WCA | Water Contact Angle |

| WS | Water Solubility |

| WVP | Water Vapor Permeability |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| YI | Yellow Index |

References

- Noreen, A.; Tabasum, S.; Ghaffar, S.; Somi, T.; Sultan, N.; Aslam, N.; Naseer, R.; Ali, I.; Anwar, F. Protein-based bionanocomposites. In Bionanocomposites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 267–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Mujahid, M.; Shahzad, S.; Rauf, Z.; Hussain, A.; Ayyash, M.; Ullah, A. Exploring protein-based films and coatings for active food packaging applications: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigato, A.; Fredi, G. Effect of nanofillers addition on the compatibilization of polymer blends. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, S.; Liu, F.; Wu, J.; Khin, M.N.; Yokoyama, W.H.; Zhong, F. Effect of transglutaminase crosslinking on solubility property and mechanical strength of gelatin-zein composite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 116, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lan, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chi, H.; Meng, Q.; Fan, F.; Tang, J. Properties of gelatin-zein films prepared by blending method and layer-by-layer self-assembly method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 292, 139172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, M.; Lorén, N.; Stading, M. Characterization of Phase Separation in Film Forming Biopolymer Mixtures. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, S.; Liu, F.; Khin, M.N.; Yokoyama, W.H.; Zhong, F. Improvement of the water resistance and ductility of gelatin film by zein. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 105, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xiao, J.; Cai, J.; Liu, H. Phase separation behavior in zein-gelatin composite film and its modulation effects on retention and release of multiple bioactive compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 109, 106105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Hossen, A.; Zeng, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, S.; Qin, W.; Liu, Y. Gelatin-based composite films and their application in food packaging: A review. J. Food Eng. 2022, 313, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Giménez, B.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Montero, M.P. Functional and bioactive properties of collagen and gelatin from alternative sources: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.-C.; Yin, S.-W.; Yang, X.-Q.; Tang, C.-H.; Wen, S.-H.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, B.-J.; Wu, L.-Y. Surface modification of sodium caseinate films by zein coatings. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Cheryan, M. Zein: The industrial protein from corn. Ind. Crops Prod. 2001, 13, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ruiz--Garcia, L.; Qian, J.; Yang, X. Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review and Future Trends. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawood, F.K. Multi-criteria optimization of polymer selection for biomedical additive manufacturing using analytic hierarchy process. Mater. Des. 2025, 256, 114369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pant, S. Analytical hierarchy process for sustainable agriculture: An overview. MethodsX 2023, 10, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, F.H.M.; Volcov, V.C.; Moreira, M.F.; Silva, A.S.; Moreira, M.Â.L.; Fávero, L.P.; dos Santos, M. Hiring newly graduated nurses in the post-pandemic context: Integrated multicriteria assessment using the AHP and TOPSIS methods. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 266, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoveidafard, A.; Moradinia, S.F.; Golchin, B.; Ghaffari, A. Identification of required stations for autonomous vehicles using AHP and TOPSIS method with GIS approach. Sustain. Futur. 2025, 10, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Jiang, L.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Sun, D.; Ma, Q.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W. Flexibility, dissolvability, heat-sealability, and applicability improvement of pullulan-based composite edible films by blending with soluble soybean polysaccharide. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 215, 118693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easdani, M.d.; Liu, F.; Van Impe, J.F.M.; Ahammed, S.; Chen, M.; Zhong, F. Modulating hydrophobic and antimicrobial gelatin-zein protein-based bilayer films by incorporating glycerol monolaurate and TiO2 nanoparticles. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 46, 101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Huang, Z.; Yang, F.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, C. The effect of polylactic acid-based blend films modified with various biodegradable polymers on the preservation of strawberries. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 45, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D882-18; D20 Committee, Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, S.; Lu, K.; Tang, K.; Liu, J. Heat sealable soluble soybean polysaccharide/gelatin blend edible films for food packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM F88/F88M-09; F02 Committee, Test Method for Seal Strength of Flexible Barrier Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kanmani, P.; Lim, S.T. Development and characterization of novel probiotic-residing pullulan/starch edible films. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt, A.; Toker, O.S.; Tornuk, F. Effect of xanthan and locust bean gum synergistic interaction on characteristics of biodegradable edible film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Cui, J.; Yang, L.; Su, H.; Yang, P.; Pan, J. Colorimetric films based on pectin/sodium alginate/xanthan gum incorporated with raspberry pomace extract for monitoring protein-rich food freshness. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E96/E96M-16; C16 Committee, Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, S.; Easdani, M.; Liu, F.; Zhong, F. Encapsulation of Tea Polyphenol in Zein through Complex Coacervation Technique to Control the Release of the Phenolic Compound from Gelatin–Zein Composite Film. Polymers 2023, 15, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhong, F.; Li, Y.; Shoemaker, C.F.; Xia, W. Preparation and characterization of pullulan–chitosan and pullulan–carboxymethyl chitosan blended films. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Huang, Y.; Lan, L.; Xu, D.; Dan, Y.; Jiang, L. UV/blue-light-blocking polylactide films derived from bio-sources for food packaging application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.D.; Pacheco, T.F.; de Santi, A.D.; Manarelli, F.; Bozzo, B.R.; Brienzo, M.; Otoni, C.G.; Azeredo, H.M. From bulk banana peels to active materials: Slipping into bioplastic films with high UV-blocking and antioxidant properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 140709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlak, M.E.; Uzuner, K.; Kirac, F.T.; Ozdemir, S.; Dundar, A.N.; Sahin, O.I.; Dagdelen, A.F.; Saricaoglu, F.T. Production and characterization of biodegradable bi-layer films from poly(lactic) acid and zein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tural, S.; Turhan, S. Properties of Edible Films Made From Anchovy By-Product Proteins and Determination of Optimum Protein and Glycerol Concentration by the TOPSIS Method. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2017, 26, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadat-Seyedbokaei, F.; Felix, M.; Bengoechea, C. Zein as a basis of green plastic materials: Modifications, applications, and processing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 331, 148287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susi, H.; Byler, D.M. Fourier Deconvolution of the Amide I Raman Band of Proteins as Related to Conformation. Appl. Spectrosc. 1988, 42, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaber, R.; Arthur, C.J.; Depciuch, J.; Łach, K.; Raciborska, A.; Michalak, E.; Cebulski, J. Distinguishing Ewing sarcoma and osteomyelitis using FTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, K.; Yu, D.; Regenstein, J.M.; Dong, J.; Chen, W.; Xia, W. Chitosan/zein bilayer films with one-way water barrier characteristic: Physical, structural and thermal properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Yu, D.; Regenstein, J.M.; Jiang, Q.; Dong, J.; Chen, W.; Xia, W. Modulating physicochemical, antimicrobial and release properties of chitosan/zein bilayer films with curcumin/nisin-loaded pectin nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.; Zhang, M.; Xiang, L.; Xiang, A.; Zhou, H. Edible antibacterial gelatin/zein fiber films loaded with cinnamaldehyde for extending the shelf life of strawberries by electrospinning approach. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, C.; Qi, Z.; Li, L.; Zhu, P. Flame Retardancy and Thermal Behavior of Wool Fabric Treated with a Phosphorus-Containing Polycarboxylic Acid. Polymers 2021, 13, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-W.; Guan, J.-P.; Chen, G.; Yang, X.-H.; Tang, R.-C. Adsorption and Flame Retardant Properties of Bio-Based Phytic Acid on Wool Fabric. Polymers 2016, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, K.; Ishida, K.; Masunaga, H.; Hikima, T.; Numata, K. Influence of Water Content on the β-Sheet Formation, Thermal Stability, Water Removal, and Mechanical Properties of Silk Materials. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsuwan, K.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T. Physical/thermal properties and heat seal ability of bilayer films based on fish gelatin and poly(lactic acid). Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 77, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lan, Q. Experimental evidence for immiscibility of enantiomeric polymers: Phase separation of high-molecular-weight poly(ʟ-lactide)/poly(ᴅ-lactide) blends and its impact on hindering stereocomplex crystallization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnaar, G.; Brusseau, M.L. Pore-Scale Characterization of Organic Immiscible-Liquid Morphology in Natural Porous Media Using Synchrotron X-ray Microtomography. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 8403–8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Kang, X.; Liu, Y.; Feng, F.; Zhang, H. Characterization of gelatin/zein films fabricated by electrospinning vs solvent casting. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Xiao, J. Multilayer zein/gelatin films with tunable water barrier property and prolonged antioxidant activity. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 19, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Cai, Q.; Li, Q.; Xue, L.; Jin, R.; Yang, X. Effect of solvent on surface wettability of electrospun polyphosphazene nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 3393–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, D.; Lai, T.K.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Gopakumar, D.A.; Hasan, M.; Owolabi, F.A.T.; Aprilia, N.A.S.; Rizal, S.; Khalil, H.P.S.A. Development of seaweed-based bamboo microcrystalline cellulose films intended for sustainable food packaging applications. BioResources 2019, 14, 3389–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Norisuye, T.; Tran-Cong-Miyata, Q. Light Scattering Study on the Mode-Selection Process in Reversible Phase Separation of a Photoreactive Polymer Mixture. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 14950–14956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessa, D.J.; Eller, F.J.; Palmquist, D.E.; Lawton, J.W. Improved methods for decolorizing corn zein. Ind. Crops Prod. 2003, 18, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prietto, L.; Mirapalhete, T.C.; Pinto, V.Z.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Vanier, N.L.; Lim, L.-T.; Dias, A.R.G.; Zavareze, E.d.R. pH-sensitive films containing anthocyanins extracted from black bean seed coat and red cabbage. LWT 2017, 80, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Bhartiya, P.; Singh, A.; Dutta, P.K. Preparation, physicochemical and biological evaluation of quercetin based chitosan-gelatin film for food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 227, 115348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Wang, H.; Dai, H.; Fu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhu, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and characterization of gelatin films by transglutaminase cross-linking combined with ethanol precipitation or Hofmeister effect. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Ó.L.; Reinas, I.; Silva, S.I.; Fernandes, J.C.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Pereira, R.N.; Vicente, A.A.; Poças, M.F.; Pintado, M.E.; Malcata, F.X. Effect of whey protein purity and glycerol content upon physical properties of edible films manufactured therefrom. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.M.; Piccirilli, G.N.; Delorenzi, N.J.; Verdini, R.A. Effect of different combinations of glycerol and/or trehalose on physical and structural properties of whey protein concentrate-based edible films. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 56, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegan, H.A.; Dodd, F.J. A note on saaty’s random indexes. Math. Comput. Model. 1991, 15, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic steps for film performance evaluation using the AHP-TOPSIS approach.

Figure 1.

Schematic steps for film performance evaluation using the AHP-TOPSIS approach.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of the gelatin/zein film and (b) enlarged amide I peak.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of the gelatin/zein film and (b) enlarged amide I peak.

Figure 3.

(a) XRD pattern and (b) CI of gelatin/zein film (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

(a) XRD pattern and (b) CI of gelatin/zein film (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

(a) TG and (b) DTG curves of gelatin/zein films.

Figure 4.

(a) TG and (b) DTG curves of gelatin/zein films.

Figure 5.

(a) Surface and (b) cross-sectional SEM micrographs of gelatin/zein films.

Figure 5.

(a) Surface and (b) cross-sectional SEM micrographs of gelatin/zein films.

Figure 6.

TS and EAB of gelatin/zein blend films (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

TS and EAB of gelatin/zein blend films (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Heat-sealing strength of gelatin/zein film (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Heat-sealing strength of gelatin/zein film (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

WS of gelatin/zein films (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

WS of gelatin/zein films (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

(a) WVP and (b) OP of gelatin/zein films (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

(a) WVP and (b) OP of gelatin/zein films (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 10.

(a) Visual appearance of film on printed university logo paper and (b) transparency of gelatin/zein films. (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 10.

(a) Visual appearance of film on printed university logo paper and (b) transparency of gelatin/zein films. (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 11.

(a) UV-Vis spectra and (b) UV blocking ability of gelatin/zein film (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Figure 11.

(a) UV-Vis spectra and (b) UV blocking ability of gelatin/zein film (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Classification of sub-criteria representing the main criteria.

Table 1.

Classification of sub-criteria representing the main criteria.

| Main Criteria | Sub-Criteria |

|---|

| Mechanical properties | TS |

| EAB |

| Heat-sealing | Seal Strength |

| Water resistance | WCA |

| WS |

| Gas barrier | WVP |

| OP |

| Optical properties | UV Block |

| Transparency |

| Color |

Table 2.

Weight loss of gelatin/zein films at different stages on TGA.

Table 2.

Weight loss of gelatin/zein films at different stages on TGA.

| | Peak 1

(°C) | Weight Loss

(%) | Peak 2

(°C) | Weight Loss

(%) | Peak 3

(°C) | Weight Loss

(%) |

|---|

| Gel | 103 | 2.82 | 245 | 15.65 | 308 | 37.78 |

| GZ20 | 100 | 3.07 | 249 | 16.03 | 316 | 38.42 |

| GZ40 | 97 | 2.87 | 261 | 18.61 | 328 | 48.87 |

| GZ60 | 101 | 1.40 | 258 | 16.00 | 330 | 47.53 |

| GZ80 | 83 | 2.11 | 277 | 20.26 | 331 | 50.45 |

| Zein | 79 | 1.71 | 275 | 17.53 | 308 | 31.42 |

Table 3.

WCA of gelatin/zein films at 0 s, 30 s, and 60 s (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Color values of gelatin/zein films. (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Color values of gelatin/zein films. (Different letters show significant differences at p < 0.05).

| Sample Name | L* | a* | b* | ∆E | YI | Color Sample |

|---|

| STD White | 97.71 ± 0.00 | − 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |

| Gel | 94.10 ± 0.13 a | −1.01± 0.02 b | 3.32 ± 0.03 f | 4.90 ± 0.07 f | 5.04 ± 0.03 f | |

| GZ20 | 92.50 ± 0.16 b | −3.07 ± 0.01 c | 17.82 ± 0.04 e | 18.67 ± 0.05 e | 27.52 ± 0.07 e | |

| GZ40 | 92.00 ± 0.26 c | −3.43 ± 0.02 d | 24.32 ± 0.06 d | 25.07 ± 0.02 d | 37.76 ± 0.03 d | |

| GZ60 | 88.67 ± 0.12 d | −1.66 ± 0.01 e | 37.70 ± 0.01 c | 38.35 ± 0.02 c | 60.21 ± 0.07c | |

| GZ80 | 88.30 ± 0.13 d | −4.30 ± 0.01 f | 45.50 ± 0.04 b | 46.52 ± 0.02 b | 73.61 ± 0.07 b | |

| Zein | 85.20 ± 0.10 e | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 52.10 ± 0.02 a | 53.46 ± 0.00 a | 87.36 ± 0.06 a | |

Table 5.

Single composite values of each sample.

Table 5.

Single composite values of each sample.

| Main Criteria | Gel | GZ20 | GZ40 | GZ60 | GZ80 | Zein |

|---|

| Mechanical Properties | 0.482 | 1.000 | 0.272 | 1.000 | 0.391 | 0.482 |

| Heat sealing ability | 0.334 | 0.429 | 0.545 | 0.665 | 0.743 | 0.334 |

| Water Resistance | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.872 | 0.044 | 0.757 | 0.008 |

| Gas Barrier Properties | 0.147 | 0.059 | 0.621 | 0.586 | 0.719 | 0.147 |

| Optical Properties | 0.160 | 0.270 | 0.721 | 0.190 | 0.628 | 0.160 |

Table 6.

Weight of importance of each main criterion through the AHP method.

Table 6.

Weight of importance of each main criterion through the AHP method.

| Mechanical Properties | Heat-Sealing Strength | Water

Resistance | Gas Barrier Properties | Optical

Properties |

|---|

| 0.218 | 0.108 | 0.128 | 0.325 | 0.221 |

Table 7.

Scores of gelatin/zein films through the TOPSIS method.

Table 7.

Scores of gelatin/zein films through the TOPSIS method.

| Sample | Distance to Positive Ideal (D+) | Distance to Negative Ideal (D−) | Closeness

Coefficient

(C) | Ranking |

|---|

| Gel | 0.111 | 0.397 | 0.781 | 2 |

| GZ20 | 0.197 | 0.265 | 0.574 | 3 |

| GZ40 | 0.449 | 0.078 | 0.149 | 6 |

| GZ60 | 0.313 | 0.177 | 0.361 | 4 |

| GZ80 | 0.350 | 0.117 | 0.250 | 5 |

| Zein | 0.065 | 0.420 | 0.867 | 1 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |