Beneath the Feathers: Hidden Burden of Serratospiculum and Other Endoparasites in Falcons Raised in Captivity in Serbia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

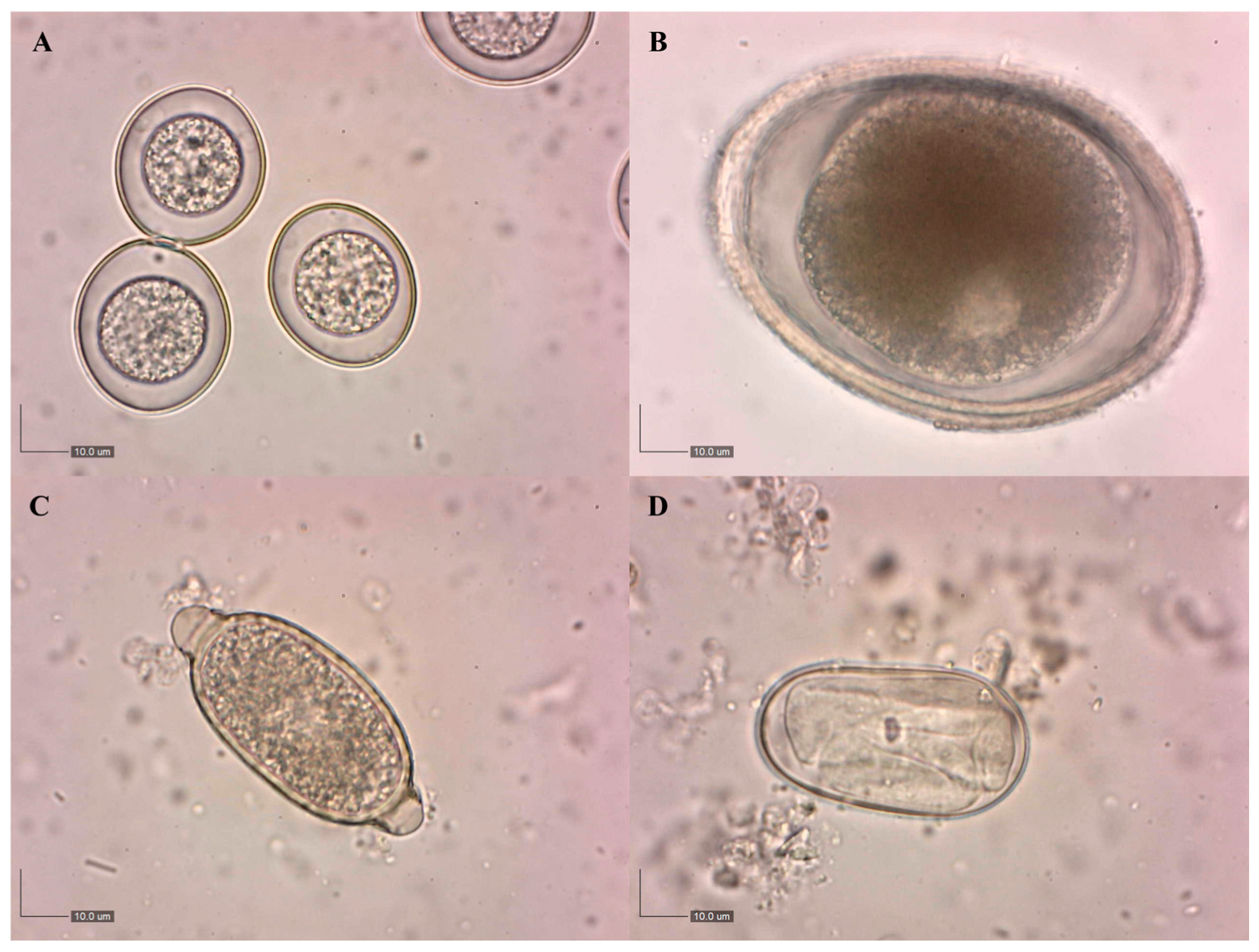

2.2. Parasitological Examination

2.3. Post Mortem Examination

2.4. Molecular Detection of Serratospiculum spp.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Endoparasites

3.2. Necropsy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puchała, K.O.; Nowak-Życzyńska, Z.; Sielicki, S.; Olech, W. Evaluation of the impact of the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus peregrinus) reintroduction process on captive-bred population. Genes 2022, 13, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponitz, B.; Schmitz, A.; Fischer, D.; Bleckmann, H.; Brücker, C. Diving-Flight Aerodynamics of a Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Pan, S.; Wang, J.; Dixon, A.; He, J.; Muller, M.G.; Ni, P.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Hou, H.; et al. Peregrine and saker falcon genome sequences provide insights into evolution of a predatory lifestyle. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krone, O. Endoparasites. In Raptor, Research and Management Techniques; Hancock House Publishers: Surrey, BC, Canada, 2007; pp. 318–328. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kharkhi, I.; Joseph, W.; Deb, A. Prevalence of faecal endoparasite ova in falcons in Qatar. Newsl. Middle East Falcon Res. Group 2013, 41, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.C.; Bain, O. Keys to the Genera of the Order Spirurida. Part 3. Diplotriaenoidea, Aproctoidea and Filarioidea; Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux: Farnham Royal, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Skrijabin, K.J. Nematodes des oiseaux du Turkestan russe. Ann. Mus. Zool. Acad. Imp. Sci. Petrograd 1916, 20, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Königová, A.; Molnár, L.; Hrčková, G.; Várady, M. The first report of serratospiculiasis in great tit (Parus major) in Slovakia. Helminthologia 2013, 50, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C. On the development, morphology, and experimental transmission of Diplotriaena bargusinica (Filarioidea: Diplotriaenidae). Can. J. Zool. 1962, 40, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, M.C.; Cole, R.A. Diplotriaena, Serratospiculum and Serratospoiculoides. In Parasitic Diseases of Wild Birds; Atkinson, C.T., Thomas, N.J., Hunter, D.B., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Samour, J.H.; Naldo, J.N. Serratospiculiasis in captive falcons in the Middle East: A review. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2001, 15, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Timimi, F.; Nolosco, P.; Al-Timimi, B. Incidence and treatment of serratospiculosis in falcons from Saudi Arabia. Vet. Rec. 2009, 165, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarello, W. Serratospiculosis in falcons from Kuwait: Incidence, pathogenicity and treatment with melarsomine and ivermectin. Parasite 2006, 13, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmanis, P.N.; Krautwald-Junghanns, M.-E.; Schmidt, V. Suspected toxicity by biological waste and air sac nematode infestation in a free-living peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2017, 65, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, N.D.; Skirnisson, K.; Nielsen, Ó.K. The parasite fauna of the gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus) in Iceland. J. Wildl. Dis. 2015, 51, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalisińska, E.; Kavetska, K.M.; Okulewicz, A.; Sitko, J. Helminths of Falco peregrinus Tunstall, 1771 from Szczecin area. Wiad. Parazytol. 2008, 54, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.; Tripepi, M.; Kinsella, J.M.; Panebianco, A.; Mattiucci, S. Helminth infestation in birds of prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) in southern Italy. Vet. J. 2010, 186, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga, I.B.; Schediwy, M.; Hentrich, B.; Frey, C.F.; Marreros, N.; Stokar-Regenscheit, N. Serratospiculosis in captive peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) in Switzerland. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2017, 31, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Geographic Information System (Version 3.36). Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2024. Available online: http://qgis.org (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Wijová, M.; Moravec, F.; Horák, A.; Lukeš, J. Evolutionary Relationships of Spirurina (Nematoda: Chromadorea: Rhabditida) with Special Emphasis on Dracunculoid Nematodes Inferred from SSU rRNA Gene Sequences. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006, 36, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrjabin, K.J. The Nematodes of Animals and Men/Essentials of Nematodology; Akademia Nauk: Moscow, Russia, 1968; Volume 12, pp. 182–183. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaleh, F.; Alyousif, M.; Elhaig, M. The emergence of Caryospora neofalconis in falcons in central Saudi Arabia. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2020, 7, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, B. A survey of the prevalence of coccidial oocysts and sporocysts in faecal samples of birds of prey (Falconiformes) and investigations into the biology of two Caryospora species (C. neofalconis n.sp. and C. kutzeri n.sp.). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany, 1982; 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, N.A.; Simpson, G.N. Caryospora neofalconis: An emerging threat to captive-bred raptors in the United Kingdom. J. Avian Med. Surg. 1997, 11, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mateuta, V.D.S.; Samour, J.H. Prevalence of Caryospora species (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) in falcons in the United Arab Emirates. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2017, 31, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Blagburn, B.L. Caryospora uptoni n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from Red-Tailed Hawks (Buteo jamaicensis borealis). J. Parasitol. 1986, 72, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allievi, C.; Zanzani, S.A.; Bottura, F.; Manfredi, M.T. Investigating Endoparasites in Captive Birds of Prey in Italy. Animals 2024, 14, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prątnicka, A.; Sokół, R.; Iller, M. Parasitic survey of birds of prey used for falconry in Poland. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 27, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldo, J.L.; Samour, J.H. Causes of morbidity and mortality in falcons in Saudi Arabia. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2004, 18, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez, A.; Martinez García, Y.; Perez Sauza, R.; Morales Luna, J.C.; Samour, J. Prevalence of Caryospora (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) oocysts in the environment of a gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus) breeding center in the United Arab Emirates. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2020, 34, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Sánchez, G.; Flores-Valle, I.T.; González-Gómez, M.; Vega-Sánchez, V.; Salgado-Miranda, C.; Soriano-Vargas, E. Caryospora neofalconis and other enteroparasites in raptors from Mexico. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2015, 4, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osche, G. On Intermediate and Accidental Hosts, and on the Ontogeny of the Labial Region in Species of Porrocaecum and Contracaecum. Z. Parasitenkd. 1959, 19, 458–484. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Mozgovoi, A.A. Ascaridata of Animals and Man and the Diseases Caused by Them (Askaridaty Zhivotnykh i Cheloveka i Vyzyvaemye imi Zabolevaniya); Israel Program for Scientific Translations: Jerusalem, Israel, 1968; pp. 335–389. [Google Scholar]

- Mawson, P.M. Ascaroid Nematodes from Canadian Birds. Can. J. Zool. 1956, 34, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission, 2nd ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tarello, W. Efficacy of Ivermectin (Ivomec®) against Intestinal Capillariosis in Falcons. Parasite 2008, 15, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Endoparasites | n = 145 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Samples | % | 95% CI | |

| Caryospora spp. | 60 | 41.4 | 33.69–49.52 |

| Porrocaecum spp. | 27 | 18.6 | 13.12–25.74 |

| Capillaria spp. | 5 | 3.4 | 1.48–7.82 |

| Serratospiculum spp. | 4 | 2.8 | 1.08–6.88 |

| Variable | N | n | % | 95% CI | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 62 | 43 | 69.4 | 57.03–79.42 | 8.809 | <0.05 |

| Female | 83 | 37 | 44.6 | 34.36–55.27 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| <2 years | 30 | 19 | 63.3 | 45.51–78.13 | 1.21 | 0.545 |

| 2–5 years | 79 | 43 | 54.4 | 43.50–64.95 | ||

| >5 years | 36 | 18 | 50.0 | 34.47–65.53 | ||

| Type | ||||||

| Hybrid falcon | 5 | 3 | 60.0 | 23.07–92.89 | 4.08 | 0.253 |

| Gyrfalcon | 23 | 17 | 73.9 | 53.53–87.45 | ||

| Peregrine falcon | 71 | 37 | 52.1 | 39.93–64.05 | ||

| Saker falcon | 46 | 23 | 50.0 | 36.12–63.88 | ||

| Location | ||||||

| Belgrade Zoo | 35 | 30 | 85.7 | 70.62–93.74 | 28.97 | <0.001 |

| Kanjiža | 7 | 0 | 0.0 | – | ||

| Pančevo | 8 | 7 | 87.5 | 52.91–99.36 | ||

| Senta | 95 | 43 | 45.3 | 35.63–55.26 | ||

| Prevention | ||||||

| Yes | 134 | 69 | 51.5 | 43.11–59.79 | 9.671 | <0.001 |

| No | 11 | 11 | 100.0 | 74.12–100.00 |

| Variable | N | n | % | 95% CI | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 62 | 38 | 61.3 | 50.68–74.38 | 17.7 | <0.001 |

| Female | 83 | 22 | 22.0 | 1.89–11.75 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| <2 years | 30 | 9 | 30.0 | 16.66–47.88 | 3.485 | 0.1751 |

| 2–5 years | 79 | 38 | 48.1 | 37.43–58.95 | ||

| >5 years | 36 | 13 | 36.1 | 22.48–52.42 | ||

| Type | ||||||

| Hybrid falcon | 5 | 3 | 60.0 | 23.07–92.90 | 3.588 | 0.3095 |

| Gyrfalcon | 23 | 13 | 56.5 | 36.81–74.36 | ||

| Peregrine falcon | 71 | 27 | 38.0 | 27.63–49.66 | ||

| Saker falcon | 46 | 17 | 37.0 | 24.52–51.40 | ||

| Preventive | ||||||

| Yes | 134 | 60 | 44.8 | 36.62–53.22 | 8.402 | <0.001 |

| No | 11 | 0 | 0.0 | − |

| Variable | N | n | % | 95% CI | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 62 | 12 | 19.4 | 11.43–30.85 | 0.03852 | 0.8444 |

| Female | 83 | 15 | 18.1 | 11.27–27.70 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| <2 years | 30 | 8 | 26.7 | 14.18–44.49 | 1.741 | 0.4187 |

| 2–5 years | 79 | 12 | 15.2 | 9.47–25.23 | ||

| >5 years | 36 | 7 | 19.4 | 9.75–35.03 | ||

| Type | ||||||

| Hybrid falcon | 5 | 0 | 0 | − | 8.611 | <0.05 |

| Gyrfalcon | 23 | 9 | 39.1 | 22.16–59.21 | ||

| Peregrine falcon | 71 | 12 | 16.9 | 9.94–27.26 | ||

| Saker falcon | 46 | 6 | 13.0 | 6.19–25.67 | ||

| Preventive | ||||||

| Yes | 134 | 21 | 15.7 | 10.48–22.77 | 10.14 | <0.01 |

| No | 11 | 6 | 54.5 | 28.01–78.73 |

| Variable | N | n | % | 95% CI | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 62 | 0 | 0.0 | − | 3.868 | <0.05 |

| Female | 83 | 5 | 6.0 | 2.60–13.39 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| <2 years | 30 | 5 | 16.7 | 7.38–33.57 | 19.85 | <0.001 |

| 2–5 years | 79 | 0 | 0.0 | − | ||

| >5 years | 36 | 0 | 0.0 | − | ||

| Type | ||||||

| Hybrid falcon | 5 | 0 | 0 | − | 5.397 | 0.1449 |

| Gyrfalcon | 23 | 0 | 0.0 | − | ||

| Peregrine falcon | 71 | 5 | 7.0 | 3.05–15.45 | ||

| Saker falcon | 46 | 0 | 0.0 | − | ||

| Preventive | ||||||

| Yes | 134 | 0 | 0.0 | − | 63.08 | <0.001 |

| No | 11 | 5 | 45.5 | 21.27–71.99 |

| Variable | N | n | % | 95% CI | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 62 | 0 | 0 | − | 3.073 | 0.0796 |

| Female | 83 | 4 | 4.8 | 1.89–11.75 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| <2 years | 30 | 2 | 6.7 | 1.18–21.32 | 4.999 | 0.0821 |

| 2–5 years | 79 | 0 | 0 | − | ||

| >5 years | 36 | 2 | 5.6 | 0.99–18.14 | ||

| Type | ||||||

| Hybrid falcon | 5 | 0 | 0 | − | 4.528 | 0.2098 |

| Gyrfalcon | 23 | 2 | 8.7 | 1.55–26.80 | ||

| Peregrine falcon | 71 | 2 | 2.8 | 0.49–9.45 | ||

| Saker falcon | 46 | 0 | 0 | − | ||

| Preventive | ||||||

| Yes | 134 | 0 | 0 | − | 63.08 | <0.001 |

| No | 11 | 4 | 36.4 | 21.27–71.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davitkov, D.; Ilic, T.; Vidakovic, M.; Solaja, S.; Nesic, V.; Jovanovic, N.M. Beneath the Feathers: Hidden Burden of Serratospiculum and Other Endoparasites in Falcons Raised in Captivity in Serbia. Birds 2025, 6, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6040063

Davitkov D, Ilic T, Vidakovic M, Solaja S, Nesic V, Jovanovic NM. Beneath the Feathers: Hidden Burden of Serratospiculum and Other Endoparasites in Falcons Raised in Captivity in Serbia. Birds. 2025; 6(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavitkov, Dajana, Tamara Ilic, Milan Vidakovic, Sofija Solaja, Vladimir Nesic, and Nemanja M. Jovanovic. 2025. "Beneath the Feathers: Hidden Burden of Serratospiculum and Other Endoparasites in Falcons Raised in Captivity in Serbia" Birds 6, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6040063

APA StyleDavitkov, D., Ilic, T., Vidakovic, M., Solaja, S., Nesic, V., & Jovanovic, N. M. (2025). Beneath the Feathers: Hidden Burden of Serratospiculum and Other Endoparasites in Falcons Raised in Captivity in Serbia. Birds, 6(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/birds6040063