Simple Summary

Social media sites, such as Facebook, representing communities of people of like-minded interests can be fruitfully engaged in citizen science to collate data that are not captured by other citizen science projects. This paper describes a methodology to capture behavioral data on Australian bird species accessing Strelitzia sp. (Bird of Paradise) flowers and seeds, thereby acting as pollinators as well as seed dispersers. A holistic search strategy including direct solicitation of images (even of low quality) and metadata via group posts on social media sites (such as Facebook) can generate a viable dataset.

Abstract

This paper outlines a methodology to compile geo-referenced observational data of Australian birds acting as pollinators of Strelitzia sp. (Bird of Paradise) flowers and dispersers of their seeds. Given the absence of systematic published records, a crowdsourcing approach was employed, combining data from natural history platforms (e.g., iNaturalist, eBird), image hosting websites (e.g., Flickr) and, in particular, social media. Facebook emerged as the most productive channel, with 61.4% of the 301 usable observations sourced from 43 ornithology-related groups. The strategy included direct solicitation of images and metadata via group posts and follow-up communication. The holistic, snowballing search strategy yielded a unique, behavior-focused dataset suitable for analysis. While the process exposed limitations due to user self-censorship on image quality and completeness, the approach demonstrates the viability of crowdsourced behavioral ecology data and contributes a replicable methodology for similar studies in under-documented ecological contexts.

1. Introduction

Birds fulfil important functions as ecosystem service providers ensuring plant propagation. The most widespread function is that of seed dispersers [1,2,3], where frugivorous birds allow plants to intensify and expand their range as well as to colonize new spaces [4]. Conversely, where birds are removed from an ecosystem, plants may maintain their status quo through suisuccession but cannot expand [5]. In addition, some avian species also act as pollinators [3,6], with insectivorous species engaging in pest removal [7,8].

While in endemic settings, plant and animal species have developed mutualistic interactions over long time scales [9], these need to develop in settings where birds that are exotic to an area are exposed to plants that are native or vice versa [9,10,11,12]. While in the former case exotic birds augment or compete with existing pollinators or seed dispersers, introduced plants are devoid of pollinators and seed dispersers unless native bird species adapt to the new plant. This paper is concerned with an instance of the latter.

Bird of Paradise plants (Strelitzia reginae, Strelitziaceae) are endemic to the Eastern Cape Province and KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa [13,14], but they have also been reported as naturalized in far-eastern India [15,16] as well as Hawai’i [17]. The allied species S. nicolai has been reported as naturalized in Sicily (Italy) [18] and in Australia [19,20]. S. reginae is widely grown as an ornamental plant in private and public gardens in the tropical and subtropical regions of Australia.

The observation of a S. reginae growing as an epiphyte in Sydney (Australia) [21] brought about the need to understand the nature and extent of that plant’s naturalization in the Australian setting as well as the processes that facilitate this to occur. With the exception of a report on the naturalization of S. nicolai in New South Wales [19] and Western Australia [20], the academic literature is silent on the matter. There are no data on which avian species pollinate the plant nor which species may be instrumental in seed dispersal.

The subsequent research strategy was two-pronged: (a) collating records of observations of S. reginae, S. alba and S. nicolai growing in non-horticultural settings in Australia [21] and (b) assessing the nature of potential pollinators as well as seed dispersers in the Australian setting using social media (reported here).

Crowdsourcing and citizen science are growing as research tools [22]. In other contexts, social media and citizen science observations have been successfully employed inter alia to collate data on crowdsourced taxidermal Murray Cod [23], assessing herpetofauna in Java [24], insect fauna in Taiwan [25], the placement of bird nests in Iran [26] or the analysis of the behaviour pattern of shrikes [27]. They have also been successfully employed to augment museum collection data from urban areas [28]. Most crowdsourcing studies draw on existing data bases as provided by natural history recording apps such as iNaturalist [29,30,31] or eBird [32]. Such data exhibit methodological biases due to the nature or their data, where, for example, larger and more colorful species are over-represented, while dull-colored or cryptic species will be under-represented [33,34,35,36,37,38]. In addition, data quality may vary, especially where identification is confirmed by fellow citizen scientists rather than specialists [39,40].

While notable exceptions exist [27,41,42,43,44], the overwhelming majority of these citizen-science-based studies focus on the presence/absence of species rather than complex behavioral data of an undefined set of species. While in some cases species behavior may be recorded in free form or preceded fields, the completeness of this is dependent on the diligence of the recorder. In consequence, such data will be patchy. For the purposes of the study of the naturalization of Strelitzia, it was necessary to collect geo-located data of species feeding on the flower or seed. Given the morphology of [45], the observations also needed to document the posture of the bird when accessing the nectar to assess whether pollen transfer would have occurred.

The aim of this research note is to describe the methodology used to compile the dataset on birds feeding on Strelitzia reginae and S.nicolai in Australia [46]. The approach broadly followed a protocol that had been developed for crowdsourcing datasets of items held in private hands for use in material culture studies [47].

2. Materials and Methods

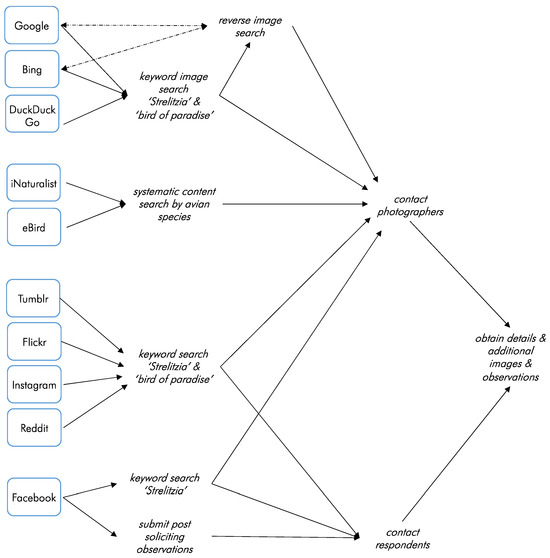

Given the non-existence of published information on birds feeding on Strelitzia reginae and S.nicolai in Australia, and given that systematic observational studies across larger areas would be impossible or financially prohibitive, it was imperative that the capture of data be as holistic as possible. Existing data were captured through searches in specialist natural history sites, the general world wide web, image hosting sites and social media platforms. Where appropriate, a snowballing technique was employed by contacting photographers for specific details (location, date) of their images (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the data collection process.

2.1. Study Area

The study area encompasses the entire Australian continent. The documented distribution of horticulturally planted Strelitzia reginae and S. nicolai [29,48] is confined to the tropical, subtropical and temperate regions of the continent [49].

2.2. Study Species

The study focuses on all bird species that feed on the nectar or seeds of Strelitzia reginae and S. nicolai in Australia. The existing literature on bird interactions with Strelitzia sp. is limited to the plant’s endemic setting in South Africa, where various weaver species act as pollinators [50,51,52,53,54], as well as California, where the common yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas L.) has been documented [55]. No data exist for Australia.

2.3. Data Search Methods

2.3.1. Natural History Recording Apps

The natural history recording apps iNaturalist and eBird [32] were systematically searched, as well as ornithology-specific online fora, i.e., Birdforum [56], using the search terms ‘Strelitzia’ (all on 15 February and 5 March 2024). While all posts in Birdforum can be freely searched, any involvement in discussions of direct follow-ups with contributors requires registration. To access the data held by iNaturalist and eBird, formal registration is required. Searches in iNaturalist using the species confined to observations in Australia yielded 78 observations for Strelitzia reginae [29] and 299 observations for S. nicolai [31]. All records were examined. A search of Birdforum yielded 24 mentions [56], all of which were examined.

As the application eBird only allows for exploring the data by bird species or by region, searches were carried out by key bird species which had been identified from other sources (see Section 2.3.2). Keyword allocation and selection of behavior characteristics (category ‘foraging and eating’) is at the discretion of the image poster, and consequently, such proved to be patchy, requiring individually examining each image for each key species: Noisy Miners (total of 10,428 images/0 images in category ‘foraging and eating’/15 images identified in systematic examination); Blue-faced honeyeaters (6868/2/5); New Holland honeyeaters (12,139/1/2); Brown honeyeaters (8644/0/4); and Lewin’s honeyeaters (5965/3/0).

2.3.2. Photo Hosting Sites, Reddit and the General WWW

The image hosting sites Flickr [57], Tumblr [58] and Instagram [59] were searched using the terms ‘Strelitzia’ and ‘Bird of Paradise’ (all on 15 or 16 February 2024). The social media site Reddit was also interrogated in a similar fashion, both as a general search (using the terms ‘Strelitzia’ and ‘Bird of Paradise’) [60] and as systematically scanning posts in dedicated sub communities r/StrelitziaNicolai [61] and r/Strelitziaceae [62]. Flickr, Tumblr and Reddit can be freely searched; any involvement in discussions of direct follow-ups with contributors requires registration. Searches in Instagram require registration.

Systematic searches of the WWW were also carried out in the same period using the search engines Google, Bing and DuckDuckGo, employing both text and image modes with the logic [Strelitzia + feeding] [63,64,65] and the logic [Strelitzia + flower + bird] [66,67,68]. Reverse image searches via Google [69] and Bing [70] aimed at locating imagery of birds or other animals interacting with S. reginae and S. nicolai.

2.3.3. Facebook

There are a large number of Facebook groups dedicated to ornithology and bird photography. Given that the research topic is somewhat atypical of the interests of most bird observers, there was a need to cast the net as wide as possible. Consequently, a large number of Facebook groups (see Appendix A) were approached rather than focusing on a small number of Facebook groups with a high number of participants. Participation on Facebook requires general registration, with additional registration (‘joining’) for each of the groups, with moderator approval required for some of these.

The data acquisition strategy was two-pronged. Searches of existing posts and solicitation were carried out. Once joined, each group was searched with keyword ‘Strelitzia’. It proved impossible on Facebook to systematically search for a phrase, thus making it impossible to search for the species’ common name. Entering ‘Bird of Paradise’ not only found posts about the plant and the various avian species ‘Bird of Paradise’ but also found all posts that merely contained the word paradise.

Solicitation was carried out via posts (Box 1) in the same Facebook groups, inviting group members to post information and images of birds feeding on Strelitzia sp. flowers. (between 20 February and April 2024). Direct communication (via Facebook Messenger) with the authors of these posts and/or replies led to snowballing, generating further imagery as well as non-image observations (Figure 1). Some of these observations were received, via direct messaging, well into 2025.

Box 1. Text of Facebook post.

Hi all,

For a research paper in an academic journal, I am looking for data that document Australian birds feeding on flowers and seeds of Strelitzia sp. (Bird of Paradise) plants (Strelitzia reginae, S. alba and S. nicolai). I am trying to determine (for the Australian setting) both pollinators and seed dispersers.

For verification purposes of the data point, I would prefer to see a photo as well please. The photo also allows me to assess the pose(s) various species use to access the nectar (or seed) in the flower.

I have trawled Flickr, iNaturalist and eBird as well as the Internet to the nth degree…am now keen to hear if you have observations to add to the dataset.

Thanks for considering

2.3.4. Data Handling

All images encountered in the data searches set out in Section 2.3.3 were downloaded and entered into a preliminary data document (a MS Word file) with a caption that identified the bird species, the location, the date of the image and the name of the observer or photographer. Each photographer was contacted to obtain permission to reproduce the image in the non-commercial data document [46] and to solicit missing location or date data. These data were also extracted into an observational database (MS Excel). Where permission to reproduce the image was not given, only the observational data were recorded.

2.3.5. Statistics

Differences in proportions were assessed using the n − 1 chi-squared test [71,72].

3. Results

The overall process, albeit laborious, was considered successful, resulting in 301 observations. Specialized naturalist sites, such as eBird and iNaturalist, only provided 9.7% of the observations, with photography sites adding another 23.6%. The bulk of observations were sourced from social media sites (61.4%), dominated by Facebook (59.8%) (Table 1). In total, 43 different Facebook groups were consulted (Appendix A). Members reacted to the posts with ‘likes’ in almost three-quarters of these (72.1%), with active participation via comments in 55.8% of the groups. In total, 87 different Facebook users provided feedback and images of species information.

Table 1.

Sources of observations (in %) (n = 301).

In total, a dataset of 301 observations of feeding on Strelitzia sp. flowers could be compiled, representing 12 different poses (Table 2) and 14 different species (Table 3) [46]. In addition, eleven observations of eight species of birds feeding on Strelitzia sp. seed were also obtained [73]. Discarding observations where the pose of the bird accessing the flower was obscured or not reported, the majority of birds will access the S. reginae flower by standing with both feet on the spathe (36.0%) or the blue petal (11.3%), or with one foot on each (28.5%). These three were the sole poses in S. nicolai, which has larger flowers as well as wider-spaced and thicker leaf stalks, whereas additional poses were documented for S. reginae (24.2%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Poses observed when accessing the flower (in %).

Table 3.

Frequency of species observed feeding on Strelitzia sp. flowers.

Considering factors of access to the nectar, which is deeply recessed, and the stability of the perches provided by the blue petal and the spathe of S. reginae, it is not surprising that having one or both feet on the spathe is significantly more common than any other position (p < 0.0001 for all poses).

The 14 different species observed as feeding on Strelitzia sp. flowers (Table 3) fall into four distinct frequency classes. Most commonly observed were Noisy Miners (39.0%) and Blue-faced Honeyeaters (25.6%), followed by New Holland honeyeaters (11.8%) and Brown honeyeaters (7.9%). The third frequency class comprised Little Wattlebirds, Red Wattlebirds and Lewin’s honeyeaters, which are represented in between 3.5 to 4,3% of all observations. The remaining species are doubles or singletons (<1% each). Statistical tests are not meaningful, as the frequency of species observations is not corrected for the overall abundance of the species in the observed areas nor for the positioning of the Strelitzia sp. plants in relation to the spatial environment (e.g., planted in open garden, near trees, houses, fences), which will impact the presence and behavior of birds.

4. Discussion

While the resulting dataset is considerable, it should be noted that the bulk of the data came from Facebook and Flickr, whereas dedicated natural history social media applications such as iNaturalist (no imagery of birds feeding on Strelitzia), Birdform (no observations from Australia) and eBird only offered very limited data. The process of assessing all posted images on eBird [32] proved very time consuming given that the number of images to be individually examined for each species was considerable (e.g., 10,428 images for Noisy Miners). This was exacerbated by the fact that images were only loaded for viewing in batches of thirty. The holistic search approach was deemed necessary; however, because keyword allocation and selection of behavior characteristics is at the discretion of the image poster, consequently, such metadata are patchy. For example, the category ‘foraging and eating’ resulted in not a single image of Noisy Miners feeding on Strelitzia, while the systematic search returned 15 results (for data on other bird species, see Section 2.3.1). All told, the search of eBird contributed 26 observations in a total of 44,044 images examined—a 0.6% ‘return’ on a time investment of five hours.

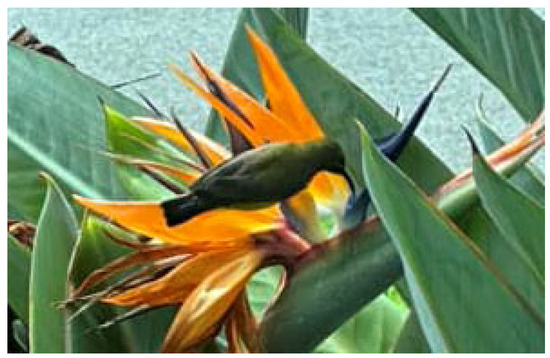

A major limitation inherent in photo hosting sites such as Flickr or Instagram, but also in sites such as eBird [32], rests in the nature of members of the public ‘publishing’ their images. Most contributors, especially those posting to photo hosting sites, tend to heavily self-censor their contributions, focusing on well-composed high-quality images (Figure 2) while avoiding posting low-quality photographs (e.g., Figure 3)—even though such images can hold the same observational value for academic research as visually outstanding images.

Figure 2.

An example of a well-composed ‘high-quality’ photograph of a Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala) feeding on the nectar of a Strelitzia reginae flower. Observed at Bellingen (NSW) in June 2022 (photo courtesy of Bobbi Marchini via Facebook) [74,75].

Figure 3.

An example of a ‘low-quality’ photograph that thus still yields useable data: Brown honeyeater (Lichmera indistincta) accessing the nectar of a Strelitzia reginae flower. Observed at Douglas, Townsville, Qld (photo courtesy of Jenny Quaill via Facebook) [76].

The self-censorship of image quality also extends to some Facebook groups, where, with the exception of one individual, no responses were received from groups that focus on bird photography. The calls for images and observations made in the various ornithology-focused Facebook groups, however, allowed contributors to respond to the request with information and thus for the inclusion of images that otherwise would never have been posted. This is encapsulated by the comment of one contributor who initially noted “but I’m embarrassed if you credit it—not my best photography effort!” [77]. The calls on Facebook caused several contributors to either publicly post additional imagery or supply this via direct messaging. This included imagery that had either been shot at different occasions or as part of the same feeding event showing different poses.

The methodology espoused here is, of course, not without its own limitations. Citizen science data tend to be biased towards larger and more colorful species [37,78], which can bias studies based on presence/absence data or relative frequency of species. When flowering, Strelitzia, with their colorful and strikingly shaped petals, are very conspicuous plants. They are eminently photogenic in their own right and also provide a colorful setting for bird photography, both of which greatly enabled the quantity of collected data.

As the data collection was carried out to identify bird species accessing Strelitzia flowers and to understand poses that could affect pollination, the author was not concerned with the effects of multiple images of the same individual bird visiting a flower on the same or subsequent days. Thus, on some occasions, snowballing, by asking contributors whether they had additional images of the same or other earlier or later events, yielded additional images of the same event, which is obviously pseudoreplication. If this were of concern, data cleaning would need to be carried out to avoid this. In instances where the photographer cannot be contacted, this can be resolved by examining the EXIF data of images where available or by excluding doubtful examples.

Finally, a comment on the time that was devoted to the creation of the dataset. While no formal log was kept, it is estimated that approximately 35 h was invested. The efforts comprised three solid blocks required for searching eBird (ca. 5 h), the World Wide Web (incl. Flickr, etc.) (ca. 5 h) and joining the various Facebook groups and setting up the posts (ca. 5 h), as well as monitoring Facebook. Thereafter, only asynchronous monitoring of the Facebook groups and responses via comments, direct messaging or emails was required. This would have amounted to approximately 1 h a day for the first week after the initial posts and about 15 min per day for the remainder of the eight weeks, totaling about 20 h of interaction. The amount of time invested in the Strelitzia study should only be taken as indicative for other studies, as the responsiveness of the audience(s) will determine the amount of effort to be invested. In addition, only a very small proportion of the members of the various Facebook groups responded (Appendix A). The investment required would increase in proportion with an increase in participants, whereby it is not necessarily ensured that this will result in the same proportionate increase in observations.

5. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates the feasibility and value of using a holistic, crowdsourced data acquisition strategy to investigate ecological interactions of ornamental species on the verge of becoming naturalized in an Australian context. In the absence of systematic observational studies or published ecological data on pollination and seed dispersal of the horticulturally popular Bird of Paradise species in Australia, the methodology employed here enabled the compilation of a substantial dataset comprising 301 flower-visitation events and 11 instances of seed feeding, representing 14 bird species and a diversity of behavioral poses relevant to pollination potential.

The project highlights both the suitability and limitations of citizen science platforms and social media as sources of ecological data. Specialized platforms such as eBird and iNaturalist contributed relatively little, largely due to the underutilization or absence of behavioral metadata tags. In contrast, the dynamic engagement facilitated through Facebook yielded the vast majority of observations, particularly through direct solicitation and follow-up communication. While issues such as image quality bias and inconsistent metadata remain challenges, the use of inclusive outreach strategies prompted contributors to share ecologically valuable imagery that may otherwise have remained private.

Ultimately, this paper offers a replicable model for similar studies where conventional fieldwork is constrained. The methodology found to be most suitable to crowdsource behavioral data is a combination of passive and interactive data collection. The passive mode involves the consultation of existing databases, naturalist social media (iNaturalist) as well as photo hosting sites (e.g., Flickr), while the interactive mode involves posting requests in relevant Facebook groups and subsequent monitoring as well as contacting photographers on Flickr.

The methodology underscores the growing role of digital communities and platforms in augmenting biodiversity research, especially in urban and suburban environments where naturalization processes often go under-documented.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The relevant data are included in this paper.

Acknowledgments

In am indebted to Bobbi Marchini (Bellingen, NSW) and Jenny Quaill (Douglas, Townsville, Queensland) for the permission to reproduce their images in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Facebook Groups Consulted

| Facebook Group | Group URL *) | Members | Likes | Respondents | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albury Wodonga Birders | 2007066822678074 | 1.8 k | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Amazing Honeyeaters | 1931020927140740 | 0.4 k | 2 | — | — |

| Australian Bird & Wildlife Photography | 749899642366672 | 1.6 k | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Australian Bird Identification | aubirdid | 57.4 k | 15 | 17 | 6 |

| Australian Bird Photographers Network | 318875624959268 | 4.6 k | 1 | — | — |

| Australian Bird Photography | 1394181427470927 | 9.4 k | — | — | — |

| Australian Birds | 190327417552 | 29.1 k | 2 | — | — |

| Australian Native Bird Photography | 270624117603347 | 3.3 k | — | — | — |

| Australian Native Birds | AustralianNativeBirds | 280.8 k | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| Bird and birding SA 2024 | 4553651268051583 | 1.3 k | 4 | 1 | — |

| Bird and birding Victoria 2024 | birdsandbirdingvictoria | 2.7 k | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Bird Photography Australia | birdphotographyaustralia | 82.0 k | 1 | — | — |

| Birding In Western Australia | 1709184925963427 | 2.5 k | 5 | 2 | — |

| Birding NSW | 707941821335327 | 1.4 k | — | 1 | 1 |

| Birding-Aus | 35835604880 | 3.3 k | — | 1 | 3 |

| Birds around Australia | 278256836593439 | 4.3 k | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Birds in Backyards Australia | BirdsinBackyards | 39.4 k | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Birds of Aus | 684248251595319 | 5.8 k | — | — | — |

| Birds of Australasia | 711298342784126 | 2.6 k | — | — | — |

| Birds of North East Victoria | bonev | 1 k | 3 | — | — |

| Birds of Oz | 432434936815131 | 27.8 k | 3 | 1 | — |

| Birds of the Hunter & Central Coast NSW | 465610836974827 | 3.3 k | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Birds of the Sydney Northern Beaches | 205935753226080 | 0.6 k | 2 | — | — |

| Blue Mountains Bird Observers | 666994470833608 | 2.2 k | — | — | — |

| Brisbane Birds | brisbanebirds | 13.1 | 8 | 14 | 3 |

| Central Coast Birders, NSW, Australia. | centralcoastbirders | 1.1 k | 4 | – | — |

| Cumberland Bird Observers’ Club | 176470229736140 | 2.0 k | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Darwin & Rural NT Bird Association | 2813260402232873 | 1.2 k | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Feathers and Photos | 3245915952316473 | 0.6 k | 1 | — | — |

| Field Naturalists Club of Victoria | 191099460990243 | 40.0 k | 4 | — | — |

| Lovers of Bird of Paradise Plants | 189904098591949 | 10.7 k | — | — | — |

| Macarthur Birds | 1581964245377794 | 1.4 k | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Mid North Coast Birders Network | mncbn | 0.8 k | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Native Birds in Australia | 847679366105142 | 26.9 k | — | — | — |

| NSW & ACT Birders | 1557319201151930 | 2.8 k | 1 | 1 | |

| Queensland Birding | queenslandbirding | 1.4 k | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| S.A Birds & Wildlife Photography | 2397331836975254 | 1.4 k | — | — | — |

| South Aussie Birding | southaussiebirding | 7.0 k | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| South-East Queensland Birders | 1438587753095451 | 3.2 k | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Victorian Bird Photography | 381385958675812 | 1.8 k | — | — | — |

| Victorian Birders | 631709646869379 | 10.0 k | 4 | — | — |

| Western Australian Birds | wabirds | 18.5 k | 11 | 11 | 6 |

| Western Sydney Bird Group | 430888080387411 | 2.3 k | — | — | — |

*) preceded by https://www.facebook.com/groups/ (accessed between 20 February and April 2024).

References

- Simmons, B.I.; Sutherland, W.J.; Dicks, L.V.; Albrecht, J.; Farwig, N.; García, D.; Jordano, P.; González-Varo, J.P. Moving from frugivory to seed dispersal: Incorporating the functional outcomes of interactions in plant–frugivore networks. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, W.D.; Böhning–Gaese, K.; Jetz, W. The global distribution of frugivory in birds. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clout, M.; Hay, J. The importance of birds as browsers, pollinators and seed dispersers in New Zealand forests. New Zealand J. Ecol. 1989, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Frugivory and seed dispersal revisited: Codifying the plant-centred net benefit of animal-mediated interactions. Flora 2020, 263, 151534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.S.; Buhle, E.R.; HilleRisLambers, J.; Fricke, E.C.; Miller, R.H.; Tewksbury, J.J. Effects of an invasive predator cascade to plants via mutualism disruption. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, H.A.; Paton, D.C.; Forde, N. Birds as pollinators of Australian plants. New Zealand J. Bot. 1979, 17, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, M.J. Insect herbivores and plant population dynamics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1989, 34, 531–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.A.; Maron, J.L. Long-term impacts of insect herbivores on plant populations and communities. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 2800–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D. Birds in ecological networks: Insights from bird-plant mutualistic interactions. Ardeola 2016, 63, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, K.; Mizusawa, L.; Higuchi, H. Re-established mutualism in a seed-dispersal system consisting of native and introduced birds and plants on the Bonin Islands, Japan. Ecol. Res. 2009, 24, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The connective potential of vertebrate vectors responsible for the dispersal of the Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis). Flora 2019, 259, 151468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Palms fanning out. A review of the ecological provisioning services provided by Washingtonia filifera and W. robusta in their native and exotic settings. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2020, 13, 289–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Venter, H.; Small, J.; Robbertse, P. Notes on the distribution and comparative leaf morphology of the acaulescent species of Strelitzia Ait. J. South Afr. Bot. 1975, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cron, G.V.; Pirone, C.; Bartlett, M.; Kress, W.J.; Specht, C. Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution in the Strelitziaceae (Zingiberales). Syst. Bot. 2012, 37, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, R.; Dash, S.S. A comprehensive inventory of alien plants in the protected forest areas of Tripura and their ecological consequences. Nelumbo 2021, 63, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, R.; Dash, S. Ecological impact of alien plant invasion in national parks of an Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot in India. J. Agric. Ecol. 2023, 15, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMattos, C. Non-Native Invasive Plants: Distribution and Impact at Papahana Kuaola; M.EM. Capstone Experience Final Report; University of Hawaiʻi: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Collesano, G.; Fiorello, A.; Pasta, S. Strelitzia nicolaii Regel & Körn.(Strelitziaceae), a casual alien plant new to Northern Hemisphere. Webbia 2021, 76, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Duretto, M.F.; McCune, S.; Luxton, R.; Milne, D. Strelitzia nicolai (Strelitziaceae): A new species, genus and family weed record for New South Wales. Telopea 2017, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keighery, G.; Parker, C. Systematic methods for additions and exclusions from the naturalised flora of Western Australia. West. Aust. Nat. 2024, 33, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The first record of Strelitzia reginae (Strelitziaceae) growing as an epiphyte together with commentary on avian pollinators and dispersers in the Australian setting. S. Afr. J. Bot. (submitted).

- Follett, R.; Strezov, V. An analysis of citizen science based research: Usage and publication patterns. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.; Spennemann, D.H.; Bond, J.; McCasker, N.; Kopf, R.; Humphries, P. Fishing on Facebook: Using Social Media and Citizen Science to Crowd-Source Trophy Murray Cod. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2025, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzia, A.; Kusrini, M.; Prasetyo, L. Citizen science contribution in herpetofauna data collection in Java. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; p. 012046. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Deng, D.; Lin, W.-C.; Lemmens, R.; Crossman, N.D.; Henle, K.; Schmeller, D.S. Uncertainty analysis of crowd-sourced and professionally collected field data used in species distribution models of Taiwanese moths. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 181, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnegari, M.; Hazrati, M.; Tehrani, V.K.; Dwyer, J.F. Crowd-sourced reporting of birds nesting on power lines in Iran. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2022, 46, e1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylewski, Ł.; Mikula, P.; Tryjanowski, P.; Morelli, F.; Yosef, R. Social media and scientific research are complementary—YouTube and shrikes as a case study. Sci. Nat. 2017, 104, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, D.M.; Pauly, G.B.; Kaiser, K. Citizen science as a tool for augmenting museum collection data from urban areas. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iNaturalist. Strelitzia reginae (Common Bird-of-Paradise Flower), Location: Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=6744&subview=table&taxon_id=49143 (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- iNaturalist. Strelitzia alba (White Bird-of-Paradise Flower). 2025. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/338329-Strelitzia-alba (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- iNaturalist. Strelitzia nicolai (Giant Bird-of-Paradise Flower). 2025. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=6744&subview=table&taxon_id=135250 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- eBird. eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology). 2025. Available online: https://ebird.org/home (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Aceves-Bueno, E.; Adeleye, A.S.; Feraud, M.; Huang, Y.; Tao, M.; Yang, Y.; Anderson, S.E. The accuracy of citizen science data: A quantitative review. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2017, 98, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guillén, E.; Herrera, I.; Bensid, B.; Gómez Bellver, C.; Ibáñez, N.; Jiménez-Mejías, P.; Mairal, M.; Mena-García, L.; Nualart, N.; Utjés-Mascó, M.; et al. Strengths and Challenges of Using iNaturalist in Plant Research with Focus on Data Quality. Diversity 2024, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grade, A.M.; Chan, N.W.; Gajbhiye, P.; Perkins, D.J.; Warren, P.S. Evaluating the use of semi-structured crowdsourced data to quantify inequitable access to urban biodiversity: A case study with eBird. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C. Users of a citizen science platform for bird data collection differ from other birdwatchers in knowledge and degree of specialization. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, C.T.; Poore, A.G.B.; Hofmann, M.; Roberts, C.J.; Pereira, H.M. Large-bodied birds are over-represented in unstructured citizen science data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcenò, C.; Padullés Cubino, J.; Chytrý, M.; Genduso, E.; Salemi, D.; La Rosa, A.; Gristina, A.S.; Agrillo, E.; Bonari, G.; Giusso del Galdo, G.; et al. Facebook groups as citizen science tools for plant species monitoring. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorleri, F.C.; Areta, J.I. Misidentifications in citizen science bias the phenological estimates of two hard-to-identify Elaenia flycatchers. Ibis 2022, 164, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, M.M.; Allee, L.L.; Brown, P.M.; Losey, J.E.; Roy, H.E.; Smyth, R.R. Lessons from lady beetles: Accuracy of monitoring data from US and UK citizen-science programs. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokimäki, J.; Ramos-Chernenko, A. Innovative Foraging Behavior of Urban Birds: Use of Insect Food Provided by Cars. Birds 2024, 5, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, L.M.; Major, R.E.; Davis, A.; Martin, J.M. A citizen science approach reveals long-term social network structure in an urban parrot, Cacatua galerita. J. Anim. Ecol. 2021, 90, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.A.; da Silva Júnior, G.N.; Santos, L.S.; Brito, L. Revealing new insights into Red-bellied Macaw foraging ecology through citizen photography. Austral. Ecol. 2024, 49, e13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Hetman, M.; Czechowski, P.; Grzywaczewski, G.; Sklenicka, P.; Ziemblińska, K.; Sparks, T.H. Birds drinking alcohol: Species and relationship with people. A review of information from scientific literature and social media. Animals 2020, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronestedt, E.; Walles, B. Anatomy of the Strelitzia reginae flower (Strelitziaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 2008, 6, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Birds Feeding on the Flowers of Strelitzia sp. in Australia. A Data Set; School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences, Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Datasets for Material Culture Studies: A Protocol for the systematic compilation of Items held in private hands. Heritage 2023, 6, 1977–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALA. Strelitzia reginae Aiton. 2025. Available online: https://bie.ala.org.au/species/NZOR-6-7371 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Stern, H.; De Hoedt, G.; Ernst, J. Objective classification of Australian climates. Aust. Meteorol. Mag. 2000, 49, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan, M.K. Bird pollination of Strelitzia. Ostrich. J. Afr. Ornithol. 1974, 45, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Skead, C. Weaverbird pollination of Strelitzia reginae. Ostrich. J. Afr. Ornithol. 1975, 46, 183–185. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A.J. Nectar feeding by weavers (Ploceidae) and their role as pollinators. Ostrich 2014, 85, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, G.; Mitchell, S.; Peter, C. Pollen as a reward for birds. The unique case of weaver bird pollination in Strelitzia reginae. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skead, C.J. Life History Notes on East Cape Bird Species, 1940–1990; Algoa Regional Services: Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 1997; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, F.; Daniel, F.; Fortier, A.; Hoffmann-Tsay, S.-S. Efficient avian pollination of Strelitzia reginae outside of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2011, 77, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdforum. Search ‘Strelitzia’. 2025. Available online: https://www.birdforum.net/search/5646051/?q=Strelitzia&o=relevance (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Flickr. Search ‘Strelitzia”. 2025. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/search/?text=Strelitzia (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Tumblr. Search ‘Strelitzia”. 2025. Available online: https://www.tumblr.com/tagged/Strelitzia (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Instagram. Search ‘Strelitzia”. 2025. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/explore/search/keyword/?q=strelitzia (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Reddit. Search ‘Strelitzia”. 2025. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/search/?q=%22Strelitzia%22 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Reddit. Community “Strelitiza Nicolai”. 2025. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/StrelitziaNicolai/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Reddit. Community “Strelitziaceae—Bird of Paradise, Traveller’s Palm & More”. 2025. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/Strelitziaceae/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Microsoft. Search ‘Strelitzia Feeding’. 2025. Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=strelitzia+feeding (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- DuckDuckGo. Search ‘Strelitzia Feeding”. 2025. Available online: https://duckduckgo.com/?q=Strelitzia+feeding (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Google. Search ‘Strelitzia Feeding’. 2025. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=Strelitzia%C2%A0feeding (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Google. Search ‘Strelitzia Flower Bird’. 2025. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=Strelitzia+AND+flower+AND+bird (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- DuckDuckGo. Search ‘Strelitzia Flower Bird”. 2025. Available online: https://duckduckgo.com/?q=Strelitzia+flower+bird (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Microsoft. Search ‘Strelitzia Flower Bird’. 2025. Available online: https://www.bing.com/search?q=strelitzia+flower+bird (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Google. Image Search ‘Strelitzia’ via Google. [Search Engine]. 2025. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ACQVn09vAJIiJAL_u1Rg0Wdz1wWCHM-E3w:1706679150883&q=%27Strelitzia (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Microsoft. Image Search ‘Strelitzia’ Bing. [Search Engine]. 2025. Available online: https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=Strelitzia (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Campbell, I. Chi-squared and Fisher–Irwin tests of two-by-two tables with small sample recommendations. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 3661–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedCalc Software. MEDCALC. Comparison of Proportions Calculator Version 22.032. 2018. Available online: https://www.medcalc.org/calc/comparison_of_proportions.php (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Observations of Frugivory of Strelitzia sp. Seeds in Australia. A Data Set; School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences, Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcini, B. Birds feeding on Strelitzia reginae flowers. personal communication (via Facebook) to Dirk H.R. Spennemann Personal communication. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- van Slobbe, M. Noisy Miner (Manorina melanocephala) Feeding on the Nectar of a Strelitzia reginae Flower. 2023. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=10160782860326322&set=pcb.9265546380185062 (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Quaill, J. Brown Honeyeater (Lichmera indistincta) Accessing the Nectar of a Strelitzia reginae Flower. 2024. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/AustralianNativeBirds/posts/24598324513147333/?comment_id=24624113307235120¬if_id=1705405324737476¬if_t=group_comment (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Bell, L. Strelitzia reginae plants seeding. personal communication (via Facebook) to Dirk H.R. Spennemann, Personal communication. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Randler, C.; Staller, N.; Kalb, N.; Tryjanowski, P. Charismatic species and birdwatching: Advanced birders prefer small, shy, dull, and rare species. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).