Abstract

Achieving climate neutrality, as dictated by international agreements such as the Paris Agreement, the United Nations Agenda 2030 and the European Green Deal, requires the conscription of all parts of society. The business world and, in particular, large enterprises have a leading role in this effort. Businesses can contribute to this effort by establishing a reporting and operating framework according to specific Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria. The interest of companies in the ESG framework has become more intense in the recent years, as they recognize that apart from an improved reputation, ESG criteria can add value to them and help them to become more effective in their functioning. In particular, large European companies are legally obligated by the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD—Directive 2014/95/EU) to disclose non-financial information on how they deal with social and environmental issues. In the literature, there are discussions on the extent to which a good ESG performance affects a company’s profitability, valuation, capital efficiency and risk. The purpose of this paper is to examine empirically whether a relationship between good ESG performance and the good financial condition of companies can be documented. For a sample of the top 50 European companies in terms of ESG performance (STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 Index), covering a wide range of sectors, namely Automobiles, Consumer Products, Energy, Financial Services, Manufacturing, etc., we first reviewed their reportings to see which ESG framework they use to monitor their performance. Next, we examined whether there is a pattern of better financial performance compared to other large European corporations. Our results showed that such a connection seems to exist at least for some specific parameters, while for others, such a claim cannot be supported.

Published: 20 September 2021

1. Introduction

Business leaders have started to realize that in addition to the effective management of their financial capital, it is necessary to adopt measures making them more transparent in terms of internal organization (governance) and more responsible and accountable to society. Moreover, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU) (Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095 (accessed date: 30 July 2021)), modified by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) (European Commission, Corporate sustainability reporting, https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed date: 30 July 2021)), puts additional requirements on non-financial data disclosures, according to ESG criteria.

ESG refers to a broad range of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance factors that might influence a company’s ability to generate value. It refers to the incorporation of non-financial elements into business strategy and decision-making in a corporate context. While ESG factors are referred to as non-financial, there are financial implications, as they are linked to corporate competitiveness and profitability (Athens Stock Exchange, 2019, ESG Reporting Guide 2019, https://www.athexgroup.gr/documents/10180/5665122/ENG-ESG+REPORTING+GUIDE/28a9a0e5-f72c-4084-9047-503717f2f3ff (accessed date: 30 July 2021)). According to Bloomberg Intelligence, it is estimated that global ESG assets are expected to reach $53 trillion by 2025, accounting for more than 30% of the $140.5 trillion total assets under management. Given the pandemic and the green recovery across the world, ESG criteria may help in analyzing a new set of financial risks and the harnessing of capital markets (Bloomberg Intelligence February 23, 2021, ESG assets may hit $53 trillion by 2025, a third of global AUM, https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/esg-assets-may-hit-53-trillion-by-2025-a-third-of-global-aum/ (accessed date: 30 July 2021)).

This paper focuses on the relationship between ESG performance and Business Valuation, Business Risk and Capital Structure efficiency. Using financial data of the companies in the STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 index, we empirically examined whether the adoption of ESG criteria boosts companies’ valuation, reduces their equity risk and makes them more efficient in the way they manage their funds. Our results were compared to respective literature findings.

2. Background

A positive correlation between ESG metric performance and financial performance of organizations has been suggested by many studies [1,2]. This means that ESG disclosures are valuable to investors as they provide them with financially material information.

Verheyden [3] created two different investment universes, one for large and mid-cap stocks in 23 developed and 23 emerging countries (“Global All”), and one for large and mid-cap stocks in 23 developed countries (“Global Developed Markets (DM)”). They then defined six portfolios by using the different ESG criteria for each universe and found that ESG improves risk-adjusted returns.

Giese [4] showed that the risk profile of a company, as a result of lower costs of capital and higher valuations, is affected by ESG performance. ESG information affects Business valuation and performance, both through their systematic risk profile (lower costs of capital and higher valuations) and their idiosyncratic risk profile (higher profitability and lower exposures to tail risk). The research suggests that changes in a company’s ESG characteristics may be a useful financial indicator. ESG ratings may also be suitable for integration into policy benchmarks and financial analyses.

Khan, Serafeim and Yoon [5] using a sample of firm-specific performance data on a variety of sustainability investments labelled the sustainability topics as “material” or “immaterial” based on the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Standards. They found that firms with superior performance in terms of material sustainability issues outperform firms with inferior performance in future material sustainability issues. Therefore, ESG disclosures are value-relevant and could potentially be predictive of companies’ future financial performance.

De Lucia [6] employed Machine Learning techniques to explore whether a company’s ESG practices can lead to improved financial performance in public enterprises. According to one of their key findings, the existence of a positive relationship between ESG practices and financial indicators can be suggested. This relationship appears more clearly when companies invest in environmental innovation, employee productivity and diversity and equal opportunity policies.

3. Methodology

For our analysis, we used the STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 index (https://www.boerse-frankfurt.de/sustainabilities/indices (accessed date: 30 July 2021)). This index includes companies that are global leaders in terms of ESG criteria, based on indicators measured by Sustainalytics (Sustainalytics is a company that provides high-quality, analytical environmental, social and governance (ESG) research, ratings and data to institutional investors and companies), with presence in 17 European countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

The EURO STOXX 50 Index is a European leaders’ index and provides a blue-chip representation of supersector leaders in the region. The index contains 50 stocks from 8 Eurozone countries: Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. Most of the companies of the EURO STOXX 50 Index are also included in the STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 index. Thus, to avoid double-counting, we excluded them and kept only the 19 that are solely included in the EURO STOXX 50 Index.

The list of companies in our sample is as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of companies in our sample.

At first notice, by looking at the behaviour of the STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 during the last three years, we see that COVID-19 adversely affected this index, as expected. The index price fell by almost 42% in just one month (from +20.67% on 18 February 2020 to −21.89% on 16 March 2020). The fall in the EURO STOXX 50 Index’s price, however, was sharper, recording a fall of almost 45% (from +16.08% to −29.09% in the same period). This fact may indicate a greater resilience of the companies in STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 in crises if compared to EURO STOXX 50 companies, especially if we take into account the overall behaviour of the index, which seems to recover faster (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 (blue) and EURO STOXX 50 (orange) development in the last 3 years. Source: Boerse Frankfurt.

Next, using the latest available financial data from Yahoo Finance (https://finance.yahoo.com/ (accessed date: 30 July 2021)) for each company in our sample, we calculated five indicators, namely the Beta, Total Debt/Equity, Profit Margin, Return on Assets and Return on Equity, on average per sector.

These indicators are widely used for the assessment of shareholder’s risk, capital structure efficiency, profitability and Asset and Equity efficiency, and we considered them to have provided us with a good overview of the company’s performance profile.

Four sectors, namely Personal Care, Drug and Grocery Stores, Real Estate, Retail and Telecommunications, have no representatives in the EURO STOXX 50 Index, whereas the Travel and Leisure sector has no representative in the STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 index. For our results to be comparable, therefore, we excluded those sectors from our analysis. We considered this intervention to have not harmed our conclusions, as they concern only 10 firms out of a sample of 69.

Furthermore, for simplification purposes, we grouped Banking, Insurance and Financial Services organizations under the title “Financial Services”.

4. Results and Discussion

Certain major firms are required by EU legislation to publish information about how they deal with matters such as social, environmental, corruption/bribery and human rights issues (Directive 2014/95/EU, commonly known as the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), establishes the standards for certain large corporations to disclose non-financial and diversity information). This type of information helps investors, civil society organizations, customers, policymakers and other stakeholders in evaluating major firms’ non-financial performance and encourages companies to establish a responsible business approach. Currently, non-financial reporting regulations in the EU concern large public-interest firms with more than 500 workers, namely about 11,700 major firms and organizations across the EU, including listed companies, banks, insurance companies and other companies recognized as public-interest institutions by national authorities.

In April 2021, the European Commission adopted a proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which broadens the scope of the existing reporting obligations under the NFRD to include all major corporations and corporations listed on regulated exchanges. The CSRD imposes more extensive reporting requirements, as well as an obligation to report audited information under EU sustainability reporting standards.

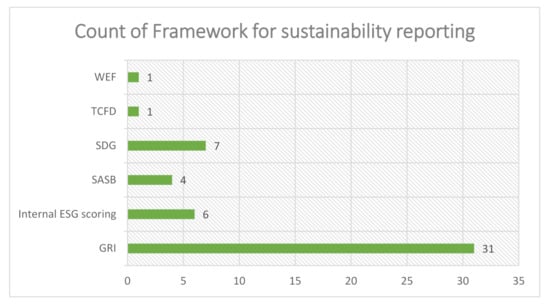

Before analyzing the data and drawing our conclusions, we considered it appropriate to assess whether the ESG reporting frameworks used by the ESG Leaders are compatible with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN Agenda 2030 or not.

Most corporations use well-established and known ESG monitoring and reporting frameworks, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a non-profit worldwide standards group that assists corporations, governments and other organizations in understanding and communicating their impacts on topics such as climate change, human rights and corruption (website: https://www.globalreporting.org/ (accessed date: 30 July 2021)), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (the SASB is a non-profit organization dedicated to the creation of sustainable accounting standards; investors, lenders, insurers and other financial capital providers are becoming more aware of the influence of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues on company financial performance, prompting the demand for standardized reporting of ESG data (website: https://www.sasb.org/ (accessed date: 30 July 2021)), the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) (the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was established by the Financial Stability Board to enhance and expand reporting of climate-related financial information (website: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/ (accessed date: 30 July 2021)) and the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) indicators (Figure 2) (‘Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism: Towards Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation’ (available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IBC_ESG_Metrics_Discussion_Paper.pdf (accessed date: 30 July 2021)), and all of these frameworks are consistent with the 17 SDGs. Six out of the 50 organizations under consideration use internal resources to develop a customized framework for ESG reporting, whereas seven of them monitor their non-financial performance by using the SDGs as a benchmark.

Figure 2.

ESG framework used by the ESG Leaders. Source: corporate websites.

In the following, the calculation of the five performance indicators mentioned in the previous section is given (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calculation of performance indicators.

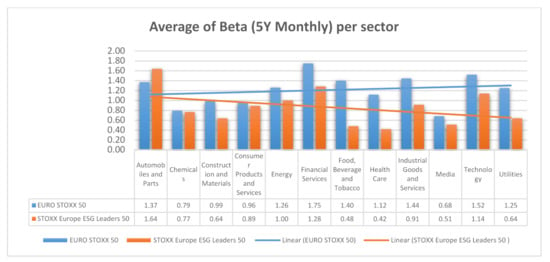

The Beta indicator expresses the volatility, hence the risk, of a stock in the market. A stock with a beta greater than 1.0 shows that the stock has a greater fluctuation than the market over time, while a stock with a beta less than 1.0 means that the volatility of the stock is less than the market. Stocks with high-betas tend to have a larger potential return, but are considered to be riskier; low-beta stocks, on the other hand, are less risky but have lower returns. From our analysis, we noticed that, in general, companies with a good ESG performance tend to have lower beta and, therefore, lower risk (Figure 3). However, this was not found to be the case for companies in the automotive sector.

Figure 3.

Average of beta (5Y Monthly) per sector.

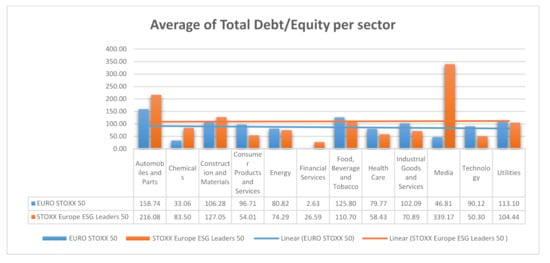

The debt-to-equity (D/E) ratio is a gearing ratio and is calculated by dividing a company’s total liabilities by its shareholder equity. It is used to assess financial leverage and comprises a very useful statistic in corporate finance, as it measures how much of a company’s activities rely upon external debt, and expresses the ability of shareholder equity to fulfil all existing obligations in the case of a business downturn. Although the comparison of the D/E ratio across different industrial sectors is sometimes problematic, since optimal levels of debt differ across the various sectors, in general, higher leverage ratios often imply that a firm or stock carries a greater risk for the shareholders.

Our analysis showed that the D/E ratio is at similar levels, regardless of whether companies have good ESG performance (Figure 4) within the same sector, except for Media companies, where the ESG demonstrated more leverage than the rest. This result agrees with [7], who suggested that when it comes to a company’s ability to raise cash or its capital structure, ESG performance is not critical. According to them, there is still a long way before sustainability is regarded as an important and well-integrated component in investment decisions. They at least did not see an obvious association between ESG performance and fund-raising ability, leading to the conclusion that sustainability measures have no impact on the optimal capital structure. However, they found that sustainability ratings can be used by a corporation to change its optimal debt levels, run more efficiently with cheaper capital, and assist managers in maximizing firm value. Having a better knowledge of how the ESG rating influences the capital structure could aid a business in its decision-making processes as regards the funding of its organization. This knowledge would enable management to better understand how the investments required to obtain the ESG grade affect the firm’s value as well as the financing dynamics [7].

Figure 4.

Average of total debt/equity per sector.

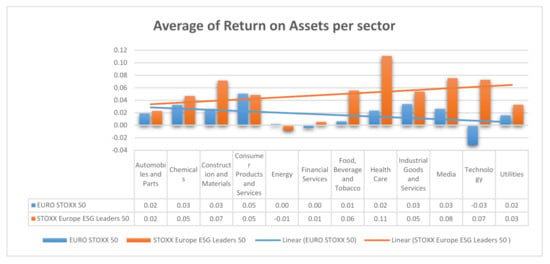

Return on assets (ROA) measures a company’s profitability to its total assets. ROA provides information about how effective a company’s management is in generating earnings from its assets. It is expressed as a percentage and, in general, the greater the ROA, the better. From our analysis, it was found that there is a clear superiority in the profitability of companies that have good ESG performance in all sectors (Figure 5). This result agrees with the finding of [8], where a positive impact of ESG performance on ROA is suggested.

Figure 5.

The average return on assets per sector.

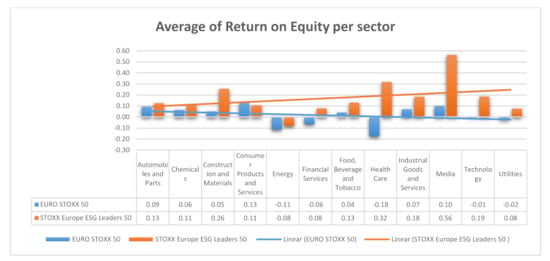

Return on equity (ROE), similarly to ROA, is a financial performance metric that is derived by dividing net income by shareholders’ equity. ROE is defined as the return on net assets since shareholders’ equity equals a company’s assets minus its debt. Therefore, the ROE is a measure of a company’s profitability to its stockholders’ equity.

Our analysis showed, as with ROA, that companies with good ESG performance have a better return on equity than the others (Figure 6). Even in the sectors with negative returns, such as the energy sector, ESG leaders demonstrate less negative return on equity than the others. Our findings on the relationship between both ROA and ROE are in line with the work of De Lucia [6], which concludes, using machine learning techniques, that a firm’s financial performance improves as a result of good ESG.

Figure 6.

The average return on equity per sector.

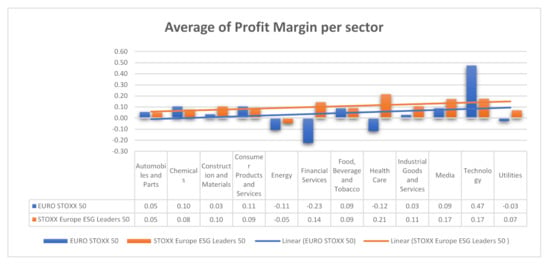

Profit margins are one of the most basic and commonly utilized financial metrics in the business world. A company’s profitability is usually measured at three levels—gross profit, operating profit and net profit. The simplest indicator of profitability is gross profit, which is calculated as the difference between sales revenue and the cost of sales, and the profit margin is derived by dividing this difference by the revenue.

Our examination does not show a clear relationship between profit margin and ESG performance. In some sectors, ESG leaders seem to have a higher profit margin, while in others, the opposite is true (Figure 7). This may be due to the specific characteristics of either the sector or the business and the way it operates to be profitable. Further, both factors that determine a company’s profit margin, namely asset turnover and sales costs, are influenced by several factors, such as area of activity, competition, international financial conditions and other parameters that seem to not be directly affected, neither positively nor negatively, by ESG performance.

Figure 7.

Average profit margin per sector.

5. Conclusions

We examined the connection between good ESG performance and sound financial results. Our sample of companies covers a wide range of industry sectors, and assuming that the tone is given from the top, we believe that our conclusions are representative of all sectors.

Business operations that comply with the established ESG principles are beneficial not only for society and the environment but also for the business itself in a variety of ways. We found that 44 companies out of the 50 included in the STOXX Europe ESG Leaders 50 index already use well-known ESG reporting frameworks that are compliant with the 17 UN SDGs. The remaining six devote resources to the development of internal systems to monitor their performance according to ESG criteria.

As far as the results on the correlation between ESG performance and financial results are concerned, our study showed that the beta coefficient, a very widely used measure for shareholders’ risk, tends to be lower in companies with strong ESG performance, thus implying a comparatively lower equity risk; firms in the automotive sector are an exception, however.

Concerning the D/E ratio, our study revealed that, except for media firms whose ESG leaders demonstrate a relatively better D/E, it does not seem to be explicitly affected by ESG performance. This result is in line with studies that suggest that ESG performance is not a critical factor for a company’s capital structure efficiency or its ability to raise funds. Further, our study showed that in some sectors, firms with strong ESG performance, in general, demonstrate a greater profit margin, but this was not found to be the case for all sectors.

Last, our analysis revealed a clear dominance in the profitability of companies that have good ESG performance compared to the rest, in all sectors. This was observed to be the case for both ROA and ROE and agrees also with results from the literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K.; methodology N.P.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, P.K. and N.P.; supervision, Phoebe Koundouri. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.boerse-frankfurt.de/sustainabilities/indices (accessed date: 30 July 2021) and here: https://finance.yahoo.com/ (accessed date: 30 July 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, W.C.; Batten, J.A.; Ahmad, A.H.; Mohamed-Arshad, S.B.; Nordin, S.; Adzis, A.A. Does ESG certification add firm value? Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 39, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyden, T.; Eccles, R.G.; Feiner, A. ESG for All? The Impact of ESG Screening on Return, Risk, and Diversification. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.-E.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG Investing: How ESG Affects Equity Valuation, Risk, and Performance. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Lucia, C.; Pazienza, P.; Bartlett, M. Does Good ESG Lead to Better Financial Performances by Firms? Machine Learning and Logistic Regression Models of Public Enterprises in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindkvist, L.; Saric, O. Sustainability Performance and Capital Structure An Analysis of the Relationship. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Business Administration, Umeå School of Business, Economics and Statistics, Umeå, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).