Synthesis, Suspension Stability, and Bioactivity of Curcumin-Carrying Chitosan Polymeric Nanoparticles †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Nanoparticle Synthesis

2.3. Particle Size Distribution

2.4. Zeta Potential

2.5. Encapsulation Efficiency

2.6. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

2.7. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

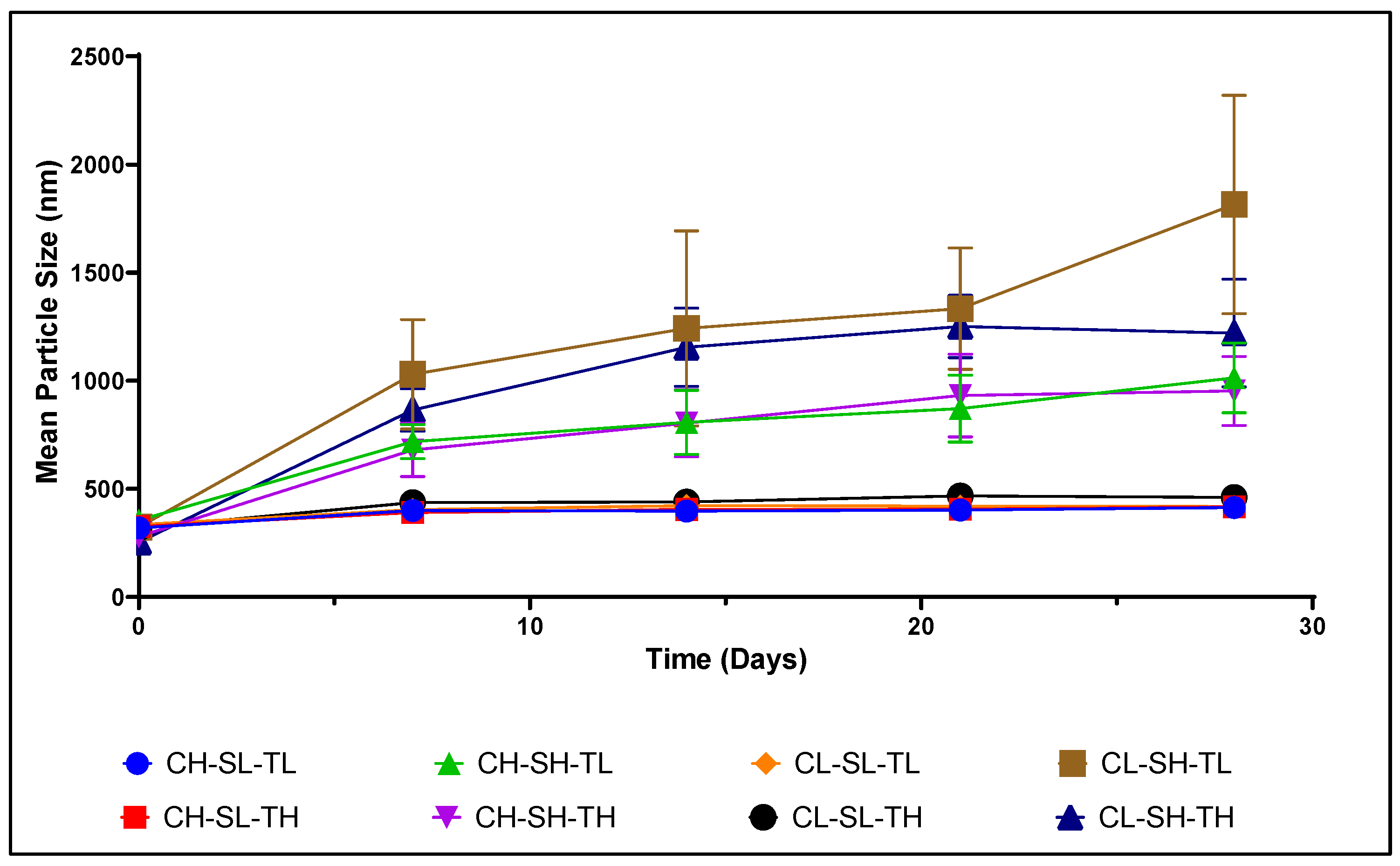

3.1. Particle Size Distribution

3.2. Zeta Potential

3.3. Encapsulation Efficiency

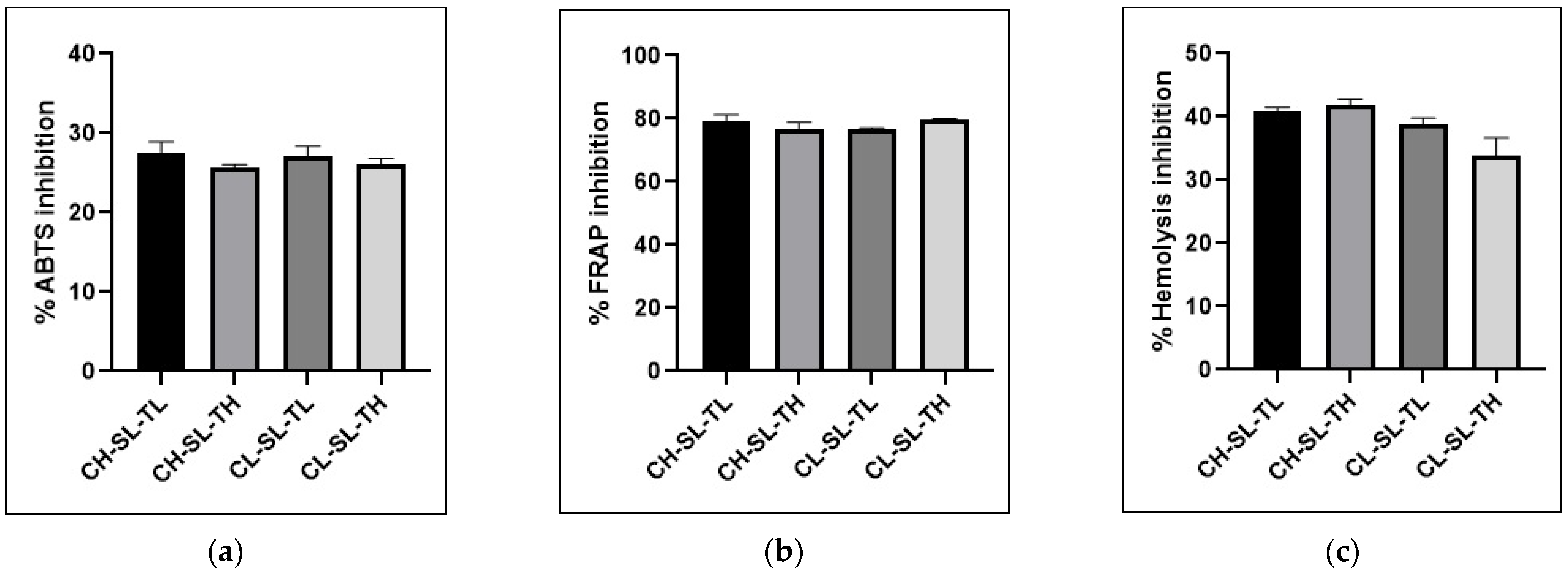

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Jagan Mohan Rao, L.; Sakariah, K.K. Chemistry and biological activities of C. longa. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A.; Gopi, S.; Gopi, S. Biological activities of curcuminoids, other biomolecules from turmeric and their derivatives—A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajan, R.; Manikandan, R. Antioxidants and cataract. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.R.; Lin, A.S.P.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Suprachoroidal Drug Delivery to the Back of the Eye Using Hollow Microneedles. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Takhistov, P.; McClements, D.J. Functional Materials in Food Nanotechnology. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, R107–R116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J. Nanoparticles: Synthesis, characteristics, and applications in analytical and other sciences. Microchem. J. 2020, 154, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Sadia, H.; Ali Shah, S.Z.; Khan, M.N.; Shah, A.A.; Ullah, N.; Ullah, M.F.; Bibi, H.; Bafakeeh, O.T.; Khedher, N.B.; et al. Classification, Synthetic, and Characterization Approaches to Nanoparticles, and Their Applications in Various Fields of Nanotechnology: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Carreiró, F.; Oliveira, A.M.; Neves, A.; Pires, B.; Venkatesh, D.N.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Eder, P.; Silva, A.M.; et al. Polymeric Nanoparticles: Production, Characterization, Toxicology and Ecotoxicology. Molecules 2020, 25, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroso-Santana, S.; Fleitas-Salazar, N. Ionotropic gelation method in the synthesis of nanoparticles/microparticles for biomedical purposes. Polym. Int. 2020, 69, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, I.; Francolini, I.; Di Lisio, V.; Martinelli, A.; Pietrelli, L.; Scotto d’Abusco, A.; Scoppio, A.; Piozzi, A. Preparation and Characterization of TPP-Chitosan Crosslinked Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Materials 2020, 13, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yetisgin, A.A.; Cetinel, S.; Zuvin, M.; Kosar, A.; Kutlu, O. Therapeutic Nanoparticles and Their Targeted Delivery Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Shrivastav, N.; Pandey, S.; Das, R.; Gaur, P. Preparation of Chitosan Nanoparticles and their In-vitro Characterization. Int. J. Life-Sci. Sci. Res. 2018, 4, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, K.; Arslan, F.B.; Tavukcuoglu, E.; Esendagli, G.; Calis, S. Aggregation of chitosan nanoparticles in cell culture: Reasons and resolutions. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 578, 119119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhakumar, S.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Ramkumar, K.M.; Raichur, A.M. Preparation of collagen peptide functionalized chitosan nanoparticles by ionic gelation method: An effective carrier system for encapsulation and release of doxorubicin for cancer drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, B.; Saikia, P.M.; Dutta, R.K. Binding and stabilization of curcumin by mixed chitosan–surfactant systems: A spectroscopic study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2012, 245, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawtarie, N.; Cai, Y.; Lapitsky, Y. Preparation of chitosan/tripolyphosphate nanoparticles with highly tunable size and low polydispersity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 157, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.S.; Morris, A.; Billa, N.; Leong, C.-O. An Evaluation of Curcumin-Encapsulated Chitosan Nanoparticles for Transdermal Delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoopathy, S.; Inbakandan, D.; Rajendran, T.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Kasilingam, R.; Gopal, D. Curcumin loaded chitosan nanoparticles fortify shrimp feed pellets with enhanced antioxidant activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 120, 111737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, H.M.; Zafar, F.; Ahmad, K.; Iqbal, A.; Shaheen, G.; Ansari, K.A.; Rana, S.; Zahid, R.; Ghaffar, S. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of anti-arthritic and anti-inflammatory potential of curcumin loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duse, L.; Baghdan, E.; Pinnapireddy, S.R.; Engelhardt, K.H.; Jedelská, J.; Schaefer, J.; Quendt, P.; Bakowsky, U. Preparation and Characterization of Curcumin Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for Photodynamic Therapy. Phys. Status Solidi (A) 2018, 215, 1700709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, M.S.; Silva Júnior, M.F.d.; Xavier-Júnior, F.H.; Veras, B.d.O.; Albuquerque, P.B.S.d.; Borba, E.F.d.O.; Silva, T.G.d.; Xavier, V.L.; Souza, M.P.d.; Carneiro-da-Cunha, M.d.G. Characterization of curcumin-loaded lecithin-chitosan bioactive nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, D.; Heruye, S.; Kumari, D.; Opere, C.; Chauhan, H. Preparation, Characterization and Antioxidant Evaluation of Poorly Soluble Polyphenol-Loaded Nanoparticles for Cataract Treatment. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mošovská, S.; Petáková, P.; Kaliňák, M.; Mikulajová, A. Antioxidant properties of curcuminoids isolated from Curcuma longa L. Acta Chim. Slovaca 2016, 9, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.; Malrautu, P.; Laha, A.; Luo, H.; Ramakrishna, S. Collagen Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery Systems and Tissue Engineering. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hong, Z.; Yi, R. Core-Shell Collagen Peptide Chelated Calcium/Calcium Alginate Nanoparticles from Fish Scales for Calcium Supplementation. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, N1595–N1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhajamee, M.; Marai, K.; Al Abbas, S.M.N.; Homayouni Tabrizi, M. Co-encapsulation of curcumin and tamoxifen in lipid-chitosan hybrid nanoparticles for cancer therapy. Mater. Technol. 2022, 37, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, M.; Jin, T.Z.; Arabi, S.A.; He, Q.; Ismail, B.B.; Hu, Y.; Liu, D. Antimicrobial and UV Blocking Properties of Composite Chitosan Films with Curcumin Grafted Cellulose Nanofiber. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Rupesh, N.; Pandit, S.B.; Chattopadhyay, K. Curcumin Inhibits Membrane-Damaging Pore-Forming Function of the β-Barrel Pore-Forming Toxin Vibrio cholerae Cytolysin. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 809782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen-Derived Peptides (mg/mL) | Sodium Chloride (M) | Tween 80® (µL) | |

| CL-SL-TL | 2 | 0.15 | 100 |

| CH-SL-TL | 4 | 0.15 | 100 |

| CL-SH-TL | 2 | 0.30 | 100 |

| CH-SH-TL | 4 | 0.30 | 100 |

| CL-SL-TH | 2 | 0.15 | 200 |

| CH-SL-TH | 4 | 0.15 | 200 |

| CL-SH-TH | 2 | 0.30 | 200 |

| CH-SH-TH | 4 | 0.30 | 200 |

| Treatment | PDI (Adim.) | Zeta Potential (mV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 28 | Day 0 | Day 28 | |

| CH-SL-TL | 0.243 ± 0.026 a | 0.193 ± 0.023 b | 51.34 ± 2.72 a | 30.23 ± 5.14 b |

| CH-SL-TH | 0.271 ± 0.017 a | 0.222 ± 0.027 b | 45.24 ± 4.90 a | 30.78 ± 2.87 b |

| CL-SL-TL | 0.226 ± 0.030 a | 0.197 ± 0.032 a | 41.12 ± 6.24 a | 31.90 ± 3.50 b |

| CL-SL-TH | 0.257 ± 0.018 a | 0.218 ± 0.019 b | 41.82 ± 4.65 a | 31.32 ± 1.73 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.s |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iza-Anaya, M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, C.U.; Varela-Pérez, A.; Cano-Sarmiento, C. Synthesis, Suspension Stability, and Bioactivity of Curcumin-Carrying Chitosan Polymeric Nanoparticles. Mater. Proc. 2025, 28, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025028006

Iza-Anaya M, Rodríguez-Fuentes CU, Varela-Pérez A, Cano-Sarmiento C. Synthesis, Suspension Stability, and Bioactivity of Curcumin-Carrying Chitosan Polymeric Nanoparticles. Materials Proceedings. 2025; 28(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025028006

Chicago/Turabian StyleIza-Anaya, Manuel, César Uriel Rodríguez-Fuentes, Abigail Varela-Pérez, and Cynthia Cano-Sarmiento. 2025. "Synthesis, Suspension Stability, and Bioactivity of Curcumin-Carrying Chitosan Polymeric Nanoparticles" Materials Proceedings 28, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025028006

APA StyleIza-Anaya, M., Rodríguez-Fuentes, C. U., Varela-Pérez, A., & Cano-Sarmiento, C. (2025). Synthesis, Suspension Stability, and Bioactivity of Curcumin-Carrying Chitosan Polymeric Nanoparticles. Materials Proceedings, 28(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025028006