Potential Coffee Distribution in a Central-Western Region of Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

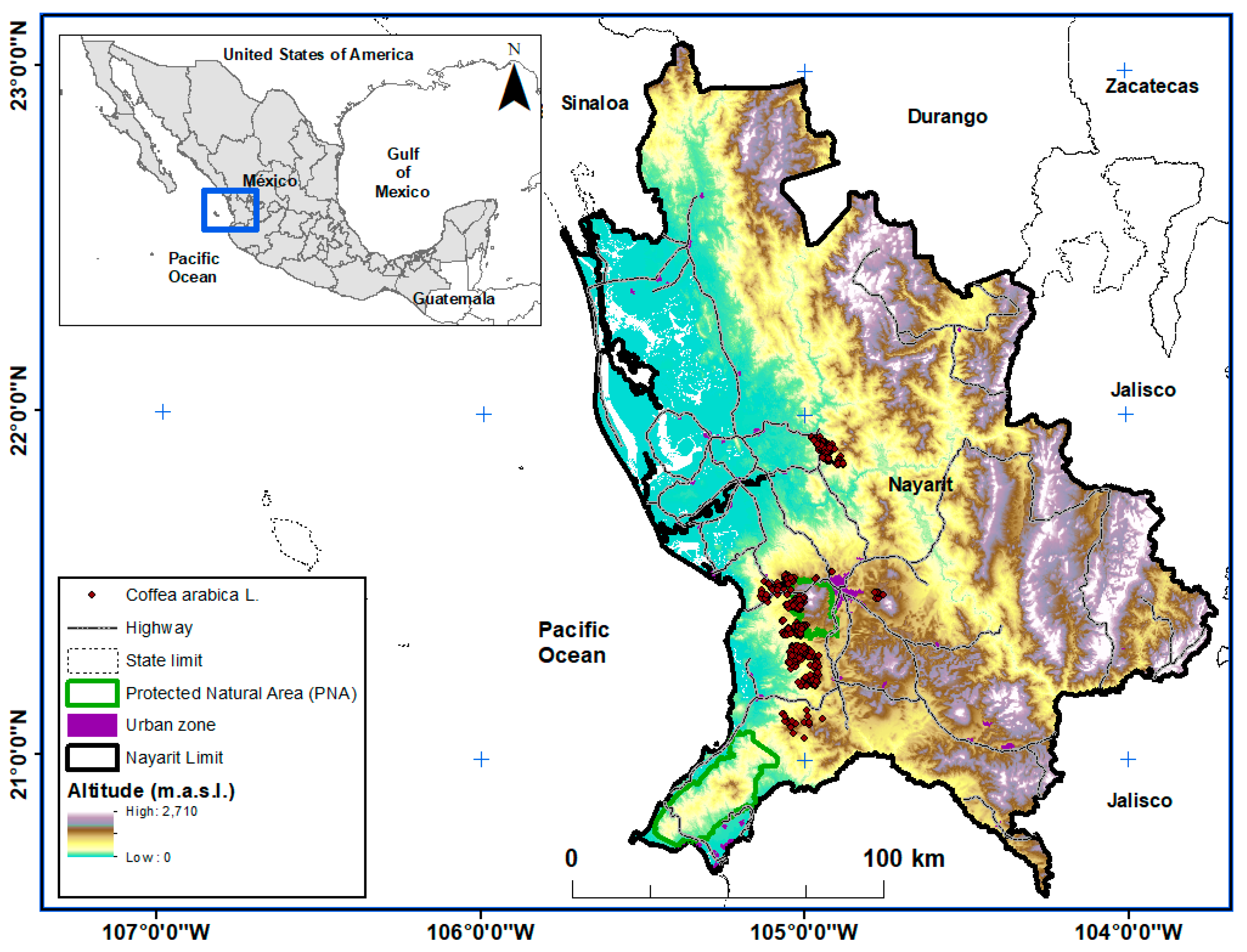

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Presence Records Data

2.3. Environmental Data

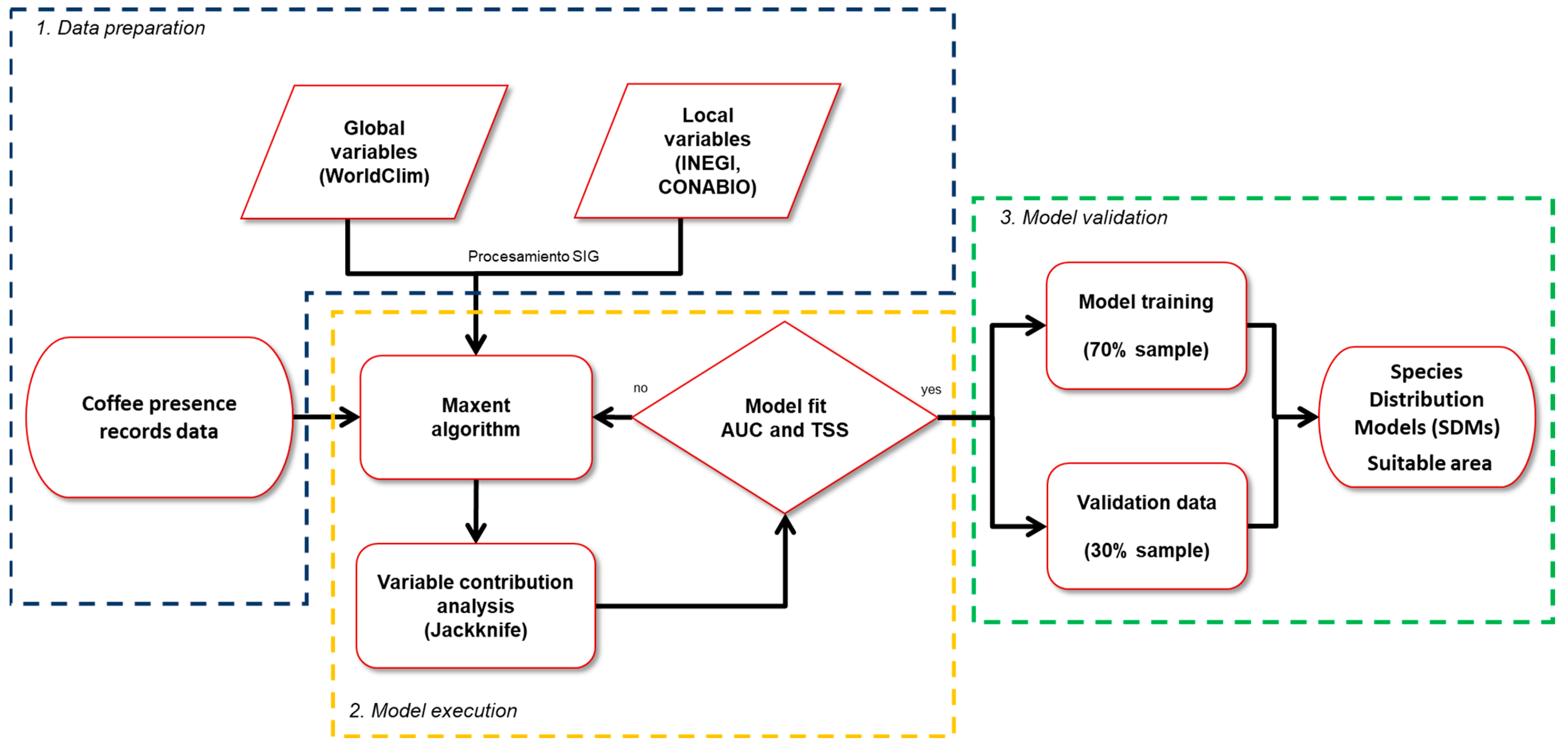

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Data Preparation

2.4.2. Variable Processing

2.4.3. Execution of the Distribution Model

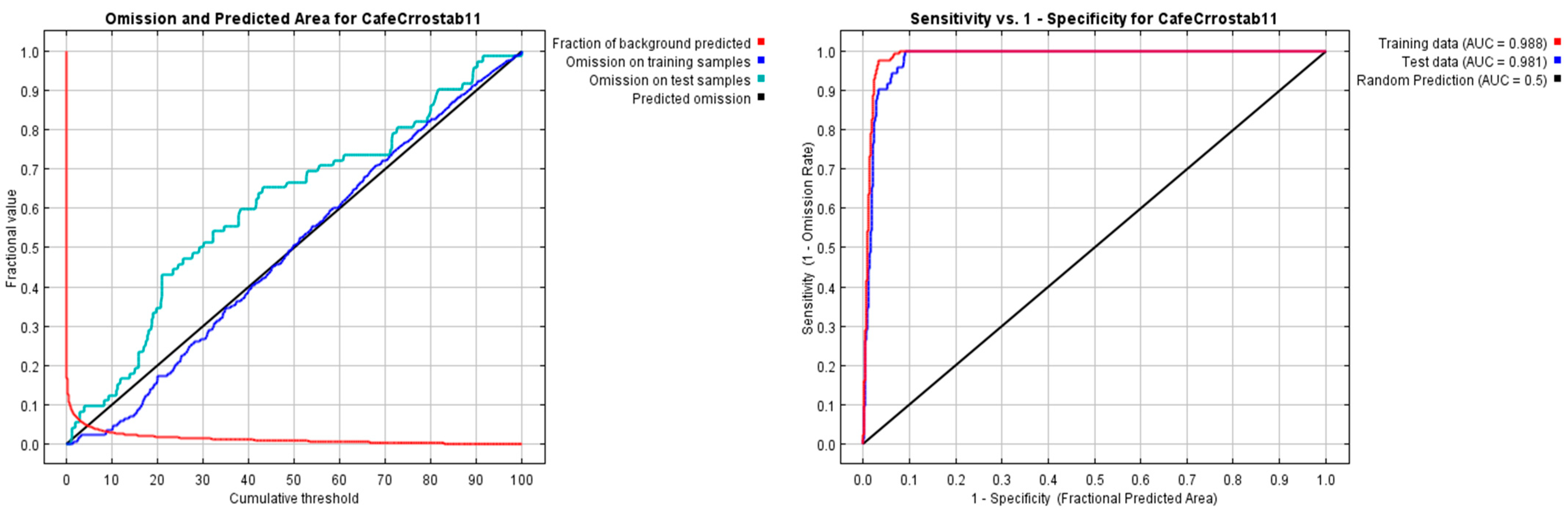

2.4.4. Model Validation

2.4.5. Potential Coffee Distribution Map

3. Results

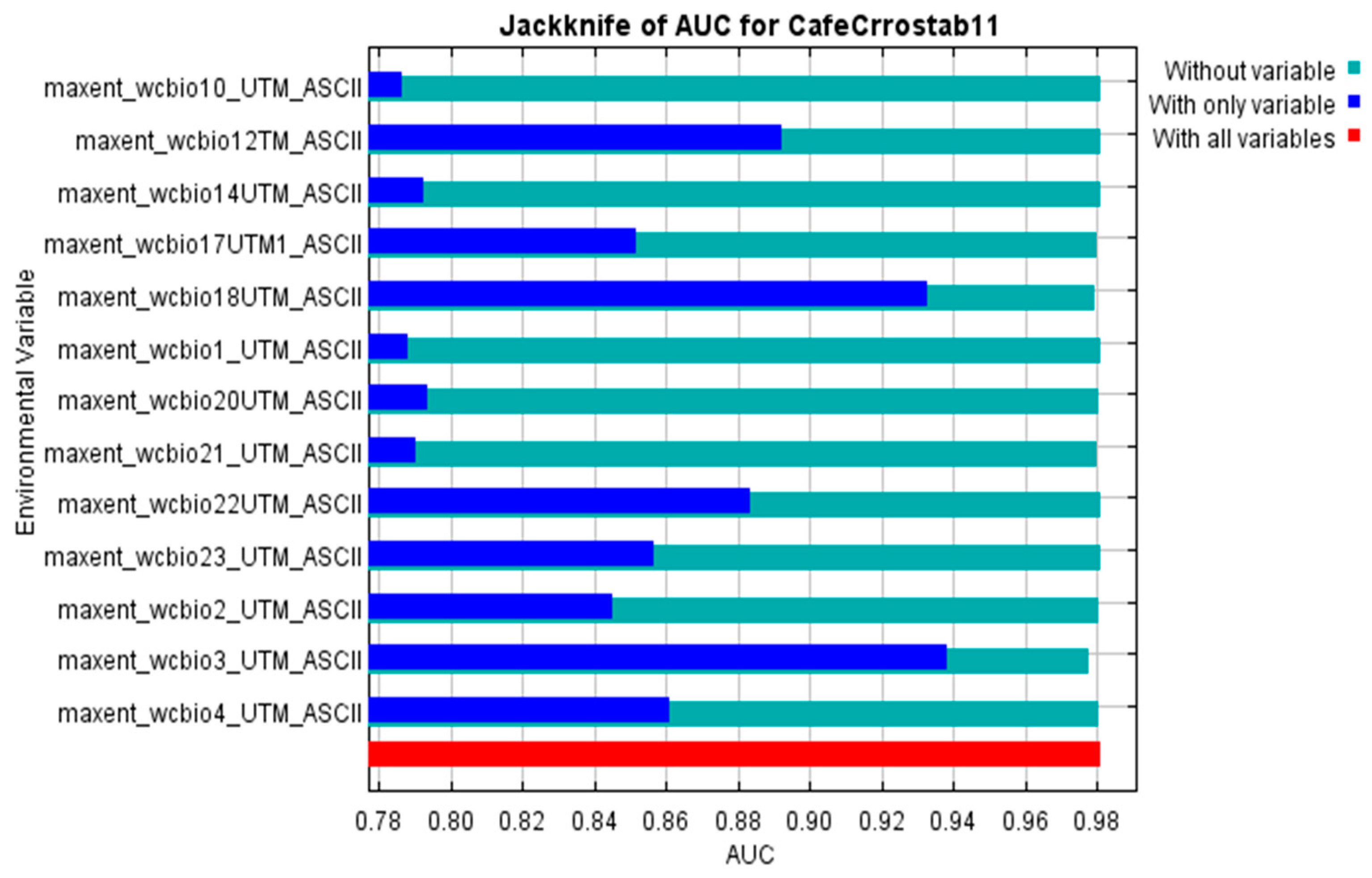

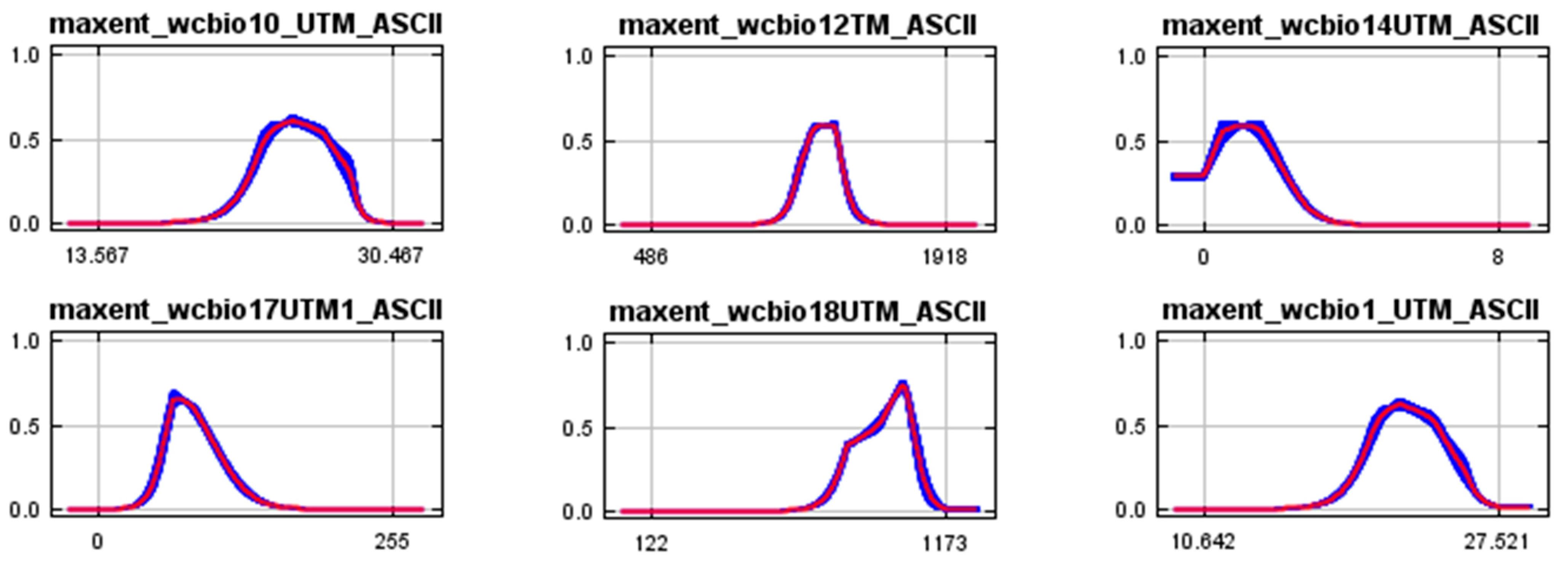

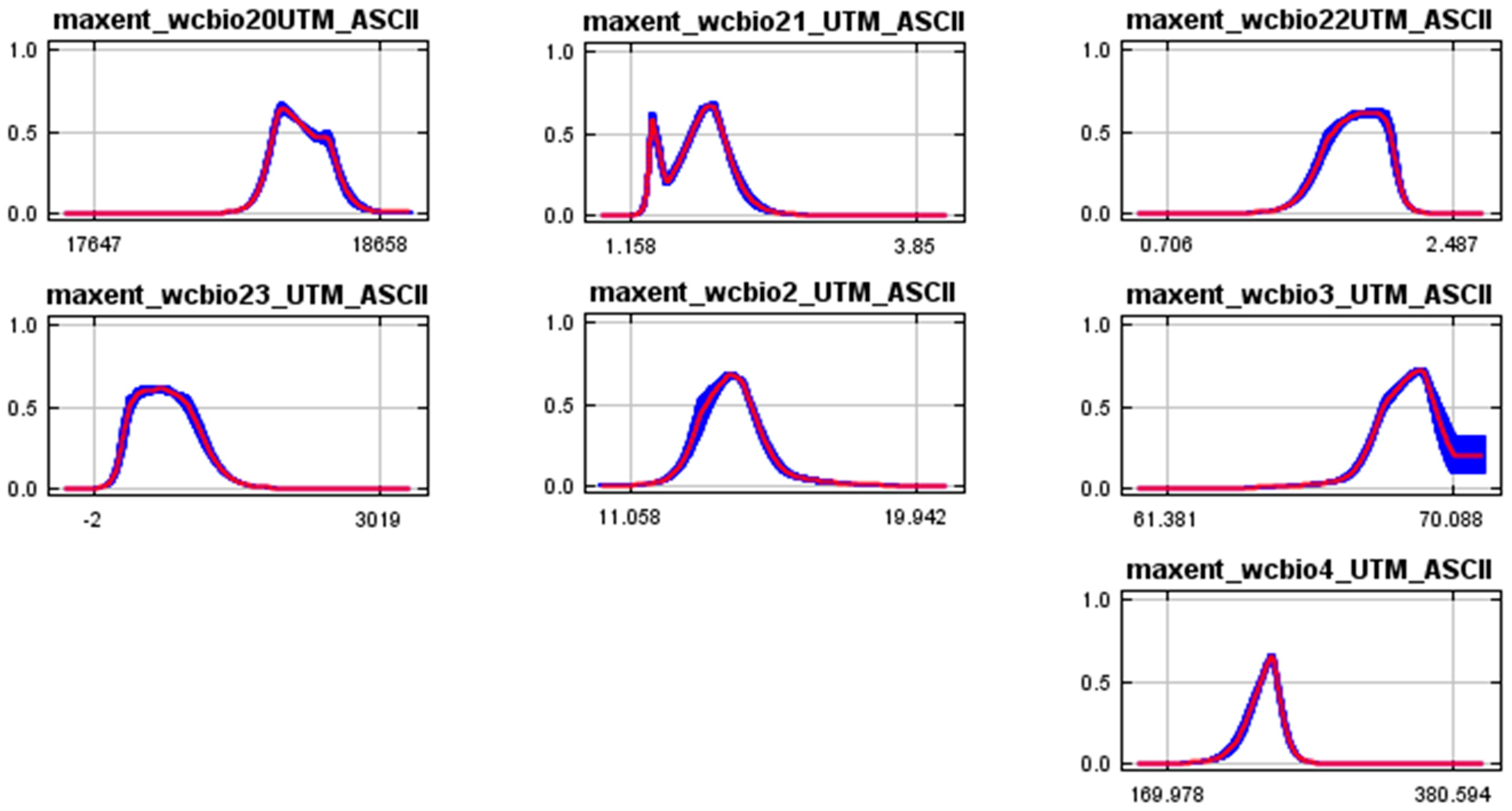

Potential Distribution Model (PDM)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OIC. Organización Internacional del Café (OIC). Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/international/multilateral/inter-governmental/ico (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- CDERSSA. Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y la Soberanía Alimentaria. Reporte el Café en México Diagnóstico y Perspectiva. 2018. Available online: http://www.cedrssa.gob.mx/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Rosas, A.J.; Escamilla, P.E.; Ruiz, R.O. Relación de los nutrimentos del suelo con las características físicas y sensoriales del café orgánico. Terra Latinoam. 2008, 26, 375–384. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S0187-57792008000400010&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Rivera, R.C.R. Competitiveness of the Mexican coffee in international trade: A comparative analysis with Brazil, Colombia, and Peru (2000–2019). Análisis Econ. 2022, 37, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.N. The Competitiveness of Vietnamese Coffe into the EU Market. 2016. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-201603303652 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Barrera, R.A.; Ramírez, G.A.G.; Cuevas, R.V.; y Espejel García, A. Modelos de innovación en la producción de café en la Sierra Norte de Puebla-México. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 26, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, P.; y Díaz, C.S. Sistemas de Cultivo de Café en México; Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo & Fundación Produce: Huatusco, México, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barrita-Ríos, E.E.; Espinosa-Trujillo, M.A.; Pérez-Vera, F.C.; Rentabilidad de Dos Sistemas de Producción de Café Cereza (Coffea Arábica L.) en Pluma Hidalgo, Oaxaca, México. Guía para Autores AGRO. 2018. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/249320086.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Vichi, F.F. La producción de café en México: Ventana de oportunidad para el sector agrícola de Chiapas. Espac. Innovación Más Desarro. 2015, 4, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.L.E.; Valdez, H.J.I.; Luna, C.M.; López, M.R. Estructura y diversidad arbórea en sistemas agroforestales de café en la Sierra de Atoyac, Veracruz. Madera Bosques 2015, 21, 69–82. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10521/2379 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Vandermeer, J.H. The Coffee Agroecosystem in the Neotropics: Combining. Ecological. and. Economic. Goals. In Tropical Agroecosystems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 159–194. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A.; Klein, A.M.; Tscharntke, T.; Tylianakis, J.M. Abandonement of coffee agroforests increases insect abundance and diversity. Agrofor. Syst. 2007, 69, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M.; Moguel, P. Coffee and sustainability: The multiple values of traditional shaded coffee. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.; Harvey, C.; Ibrahim, M.; Harmand, J.M.; Somarriba, E.; Jiménez, F. Servicios ambientales de los sistemas agroforestales. Agrofor. Am. 2003, 10, 80–87. Available online: https://repositorio.catie.ac.cr/handle/11554/6806 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Soto-Pinto, L.; Romero-Alvarado, Y.; Caballero-Nieto, J.; Segura Warnholtz, G. Woody plant diversity and structure of shade-grown-coffee plantations in Northern Chiapas, Mexico. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2001, 49, 977–987. Available online: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?pid=S0034-77442001000300018&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Pineda-López, M.; Ortiz-Ceballos, G.; Sánchez-Velásquez, L.R. Los cafetales y su papel en la captura de carbono: Un servicio ambiental aún no valorado en Veracruz. Madera Bosques 2005, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncal-García, S.; Soto-Pinto, L.; Castellanos-Albores, J.; Ramírez-Marcial, N.; De Jong, B. Sistemas agroforestales y almacenamiento de carbono en comunidades indígenas de Chiapas, México. Interciencia 2008, 33, 200–206. Available online: http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0378-18442008000300009 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Rhiney, K.; Guido, Z.; Knudson, C.; Avelino, J.; Bacon, C.M.; Leclerc, G.; Aime, M.C.; Bebber, D.P. Epidemics and the future of coffee production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023212118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamru, S.; Engida, E.; Minten, B. Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis on Coffee Value Chains in Ethiopia. IFPRI. 2020. Available online: http://essp.ifpri.info/files/2020/04/coffee_blog_April_2020.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Sanders, A.; Barba-Escoto, L.; Wiegel, J.; Mayorga-Cortes, M.; Gonzalez-Esquivel, C.; Lopez-Ramirez, M.A.; Escoto-Masis, R.M.; Morales-Galindo, E.; García-Barcena, T.S. Immediate impact of COVID-19 pandemic on farming systems in Central America and Mexico. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C.C.; Trigo, T.C.; Tirelli, F.P.; da Silva, L.G.; Eizirik, E.; Queirolo, D.; Mazim, F.D.; Peters, F.B.; Favarini, M.O.; de Freitas, T.R. Geographic distribution modeling of the margay (Leopardus wiedii) and jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi): A comparative assessment. J. Mammal. 2018, 99, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Méndez, N.; Aguirre-Planter, E.; Eguiarte, L.E.; Jaramillo-Correa, J.P. Modelado de nicho ecológico de las especies del género Abies (Pinaceae) en México: Algunas implicaciones taxonómicas y para la conservación. Bot. Sci. 2016, 94, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illoldi-Rangel, P.; Escalante, T. De los modelos de nicho ecológico a las áreas de distribución geográfica. Biogeografía 2008, 3, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Cao, W.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Xu, S. Prediction of Suitable Habitat for Lycophytes and Ferns in Northeast China: A Case Study on Athyrium brevifrons. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareghan, F.; Ghanbarian, G.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Safaeian, R. Prediction of habitat suitability of Morina persica L. species using artificial intelligence techniques. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.R.; Romero, S.M.E.; González, H.A.; Pérez, S.E.; Arriola, P.V.J. Distribución potencial de Lophodermium spp. en bosques de coníferas, con escenarios de cambio climático. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2016, 7, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.M.; Raj, M.; Kumar, S. Predicting Potential Habitat Suitability for an Endemic Gecko Calodactylodes aureus and its Conservation Implications in India. Trop. Ecol. 2017, 58, 271–282. Available online: http://216.10.241.130/pdf/open/PDF_58_2/5/5.%20Javed%20et%20al.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M.; Schapire, R.E. A maximum entropy approach to species distribution modeling. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First International Conference on Machine learning, Alberta, Canada, 4–8 July 2004; pp. 1–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promnun, P.; Kongrit, C.; Tandavanitj, N.; Techachoochert, S.; Khudamrongsawat, J. Predicting potential distribution of an endemic butterfly lizard, Leiolepis ocellata (Squamata: Agamidae). Trop. Nat. Hist. 2020, 20, 60–71. Available online: https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/tnh/article/view/198819 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Thakur, D.; Rathore, N.; Sharma, M.K.; Parkash, O.; Chawla, A. Identification of ecological factors affecting the occurrence and abundance of Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D. Don) Soo in the Himalaya. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2021, 20, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, G.J.A.; de Souza, B.I.; Paiva, L.R.F.; Souza, R.S.; Bezerra, G.L. Modeling and potential distribution of tree species relevant to the sociocultural and ecological dynamics in the Sete Cidades National Park, Piauí, Brazil. Soc. Nat. 2022, 32, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Lah, N.Z.; Yusop, Z.; Hashim, M.; Mohd Salim, J.; Numata, S. Predicting the Habitat Suitability of Melaleuca cajuputi Based on the MaxEnt Species Distribution Model. Forests 2021, 12, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, P.K.; Gaddis, K.D.; Cairns, D.M. Predicting the suitable habitat of treeline species in the Nepalese Himalayas under climate change. Mt. Res. Dev. 2018, 38, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, B.G.; Gessesse, B.; Melgani, F. MaxEnt-based modeling of suitable habitat for rehabilitation of Podocarpus forest at landscape-scale. Environ. Syst. Res. 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyo, T.; Asanok, L. Modeling habitat suitability of Dipterocarpus alatus (Dipterocarpaceae) using maxent along the chao phraya river in central Thailand. For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, P.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y. Potential geographic distribution of relict plant Pteroceltis tatarinowii in China under climate change scenarios. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Saran, S.; Kocaman, S. Role of Maximum Entropy and Citizen Science to Study Habitat Suitability of Jacobin Cuckoo in Different Climate Change Scenarios. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boral, D.; Moktan, S. Predictive distribution modeling of Swertia bimaculata in Darjeeling-Sikkim Eastern Himalaya using MaxEnt: Current and future scenarios. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Baral, S.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Yue, Y.; Dhakal, M.; Jnawali, S.R.; Chettri, N.; Racey, P.A.; Wu, Y. Will climate change impact distribution of bats in Nepal Himalayas? A case study of five species. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.N.; Gupta, H.S.; Kulkarni, N. Impact of climate change on the distribution of Sal species. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.N.; Naudiyal, N.; Wang, J.; Gaire, N.P.; Wu, Y.; Wei, Y.; He, J.; Wang, C. Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Potential Distribution of Meconopsis punicea and Its Influence on Ecosystem Services Supply in the Southeastern Margin of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 830119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Maximum entropy modeling to predict the impact of climate change on pine wilt disease in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 652500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.N.; Mbari, N.J.; Wang, S.W.; Liu, B.; Mwangi, B.N.; Rasoarahona, J.R.; Xin, H.-P.; Zhou, Y.-D.; Wang, Q.F. Modeling impacts of climate change on the potential distribution of six endemic baobab species in Madagascar. Plant Divers. 2021, 43, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, A.D.; Supriatna, J.; Nisyawati, N.; Nursamsi, I.; Sutarno, S.; Sugiyarto, S.; Sunarto, S.; Pradan, P.; Budiharta, S.; Pitoyo, A.; et al. Predicting potential impacts of climate change on the geographical distribution of mountainous selaginellas in Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21, 2252–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, D.; Guo, G.; Zhang, M.; Lang, J.; Wei, J. Potential distributions of the invasive barnacle scale Ceroplastes cirripediformis (Hemiptera: Coccidae) under climate change and implications for its management. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawi, A.S.; Gilbert, F.; Reader, T. Modelling terrestrial reptile species richness, distributions and habitat suitability in Saudi Arabia. J. Arid. Environ. 2020, 178, 104153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, D.L.; Seifert, S.N. Ecological niche modeling in Maxent: The importance of model complexity and the performance of model selection criteria. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Li, J.; Lu, H.; Lu, F.; Lu, B. Potential distribution of an invasive pest, Eu platypus parallelus, in China as predicted by Maxent. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1630–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fand, B.B.; Shashank, P.R.; Suroshe, S.S.; Chandrashekar, K.; Meshram, N.M.; Timmanna, H.N. Invasion risk of the South American tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in India: Predictions based on MaxEnt ecological niche modelling. Int. J. Trop. Insect. Sci. 2020, 40, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, S.; Reshi, Z.A.; Shah, M.A.; Charles, B. Modelled distribution of an invasive alien plant species differs at different spatiotemporal scales under changing climate: A case study of Parthenium hysterophorus L. Trop. Ecol. 2021, 62, 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stohlgren, T.J. Maxent modeling for predicting suitable habitat for threatened and endangered tree Canacomyrica monticola in New Caledonia. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ. 2009, 1, 94–98. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/JENE/article-full-text-pdf/C1CDB822968 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Aroca-Gonzalez, B.D.; Gradstein, R.; González-Nieves, L.M. ¿En peligro o no? Distribución potencial de la hepática Pleurozia paradoxa en Colombia. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Exactas Físicas Nat. 2021, 45, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Sierra, R.; Mastachi-Loza, C.A.; Díaz-Delgado, C.; Cuervo-Robayo, A.P.; Fonseca Ortiz, C.R.; Gómez-Albores, M.A.; Medina Torres, I. Spatial Risk Distribution of Dengue Based on the Ecological Niche Model of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Central Mexican Highlands. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sifuentes, A.R.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Manzanilla-Quiñones, U.; Becerra-López, J.L.; Hernández-Herrera, J.A.; Estrada-Ávalos, J.; Velázquez-Pérez, A.H. Spatial modeling of the ecological niche of Pinus greggii Engelm (Pinaceae): A species conservation proposal in Mexico under climatic change scenarios. Iforest-Biogeosci. For. 2020, 13, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Soto, C.; Monroy-Vilchis, O.; Maiorano, L.; Boitani, L.; Faller, J.C.; Briones, M.A.; Núñez, R.; Rosas-Rosas, O.; Ceballos, G.; Falcucci, A. Predicting potential distribution of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Mexico: Identification of priority areas for conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupul-Magaña, F.G.; Flores-Guerrero, U.S.; Escobedo-Galván, A.H. Distribución potencial de la tortuga mesoamericana Trachemys ornata en México Potential distribution of ornate slider Trachemys ornata in Mexico. Nota Científica 2020, 15, 1–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Rangel, L.D.; Méndez-González, J.; García-Aranda, M.A.; Nájera-Luna, J.A. Distribución potencial de 20 especies de pinos en México. Agrociencia 2018, 52, 1043–1057. Available online: https://agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/1721 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Ibarra-Montoya, J.L.; Rangel-Peraza, G.; González-Farias, F.A.; De Anda, J.; Martínez-Meyer, E.; Macias-Cuellar, H. Uso del modelado de nicho ecológico como una herramienta para predecir la distribución potencial de Microcystis sp (cianobacteria) en la Presa Hidroeléctrica de Aguamilpa, Nayarit, México. Rev. Ambiente Água 2012, 7, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Montoya, J.L.; Rangel-Peraza, G.; González-Farias, F.A.; De Anda, J.; Zamudio-Reséndiz, M.E.; Martínez-Meyer, E.; Macias-Cuellar, H. Modelo de nicho ecológico para predecir la distribución potencial de fitoplancton en la Presa Hidroeléctrica Aguamilpa, Nayarit. México. Ambiente Água-Interdiscip. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 5, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibay-Castro, L.R.; Gutiérrez-Yurrita, P.J.; López-Laredo, A.R.; Hernández-Ruíz, J.; Trejo-Espino, J.L. Potential Distribution and Medicinal Uses of the Mexican Plant Cuphea aequipetala Cav. (Lythraceae). Diversity 2022, 14, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Amaya, M.; Ruiz-Gómez, M.G.; Gómez Díaz, J.A. Análisis de la distribución de Cedrela salvadorensis Standl. (Meliaceae) e implicaciones para su conservación. Gayana. Bot. 2021, 78, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villagomez, M. Diversidad y distribución del género Persea Mill., en México. Agro Productividad 2018, 9. Available online: https://www.revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/750 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- INEGI. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- SIAP. Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Baldwin, R.A. Use of maximum entropy modeling in wildlife research. Entropy 2009, 11, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J. Transferability, sample selection bias and background data in presence-only modelling: A response to Peterson et al. Ecography 2008, 31, 272–278. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30244574 (accessed on 20 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Graham, C.H.; Anderson, R.P.; Dudik, M.; Ferrier, S. Novel methods improve prediction of species distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 2006, 29, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, W.L.; Diekmann, M.; MacTavish, L.M.; Mendelsohn, J.M.; Naidoo, V.; Wolter, K.; Yarnell, R.W. Due South: A first assessment of the potential impacts of climate change on Cape vulture occurrence. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, A.H.; Bell, J.F. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence-absence models. Environ. Conserv. 1997, 24, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merow, C.; Smith, M.J.; Silander, J.A., Jr. A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species’ distributions: What it does, and why inputs and settings matter. Ecography 2013, 36, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Tao, Y.; Xiang, J. Predicting the potential suitable distribution area of Emeia pseudosauteri in Zhejiang Province based on the MaxEnt model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allouche, O.; Tsoar, A.; Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: Prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, B.; Wan, F.; Xiao, Q.; Dai, L. Application of ROC curve analysis in evaluating the performance of alien species’ potential distribution models. Biodivers. Sci. 2007, 15, 365–372. Available online: https://www.biodiversity-science.net/EN/10.1360/biodiv.060280 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Peterson, A.T.; Soberón, J.; Pearson, R.G.; Anderson, R.P.; Martínez-Meyer, E.; Nakamura, M. Ecological Niches and Geographic Distributions. Monographs in Population Biology, 49; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, L.; Gómez, I.; Martínez-Vega, J.; Echavarría, P.; Riaño, D.; Martín, M.P. Multitemporal modelling of socio-economic wildfire drivers in central Spain between the 1980s and the 2000s: Comparing generalized linear models to machine learning algorithms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Préau, C.; Trochet, A.; Bertrand, R.; Isselin-Nondereu, F. Modeling potential distributions of three European amphibian species comparing ENFA and Maxent. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 13, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, A.; Jin, K.; Batsaikhan, M.E.; Nyamjav, J.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Xue, Y.; Sun, G.; Wu, L.; Indree, T.; et al. Predicting the current and future suitable habitats of the main dietary plants of the Gobi Bear using MaxEnt modeling. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e01032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfirio, L.L.; Harris, R.M.; Lefroy, E.C.; Hugh, S.; Gould, S.F.; Lee, G.; Bindoff, N.L.; Mackey, B. Improving the use of species distribution models in conservation planning and management under climate change. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M.; y Moguel, P. El café en México, Ecología, Cultura Indígena y Sustentabilidad. Ciencias 1996, 43, 40–51. Available online: http://www.ejournal.unam.mx/cns/no43/CNS04306.pdf?iframe=true&width=90%&height=90% (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Chávez, J. «Asumiendo la vida con una taza de café». In Desafíos y Perspectivas de la Situación Ambiental en el Perú. En el Marco de la Conmemoración de los 200 Años de Vida Republicana; Castro, A., Merino-Gómez, M.I., Eds.; INTE-PUCP: Lima, Peru, 2022; pp. 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moguel, P. Biodiversidad y cultivos agroindustriales: El caso del café. In Reporte Técnico Presentado a Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO); Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM): México City, México, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo Cortés, V.H.; Díaz Cárdenas, S. Sistema Agroindustrial Café en México: Diagnóstico, Problemática y Alternativas; Universidad Autonoma Chapingo: Chapingo, Mexico, 1994; No. 633.73 S35. [Google Scholar]

- Wintgens, J.N. Coffee: Growing, Processing, Sustainable Production. A Guidebook for Growers, Processors, Traders, and Researchers. 2004, pp. 1–976. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20113026416 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Moguel, P.; Toledo, V.M. Biodiversity conservation in traditional coffee systems of Mexico. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, B.E.; Jaramillo, A.; Cháves, B.; Franco, M. Distribución de la Floración y la Cosecha de Café en Tres Altitudes. Centro Nacional de Investigaciones de Café (Cenicafé). 2000. Available online: https://biblioteca.cenicafe.org/handle/10778/794 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Moguel, P.; Toledo, V.M. Conservar Produciendo: Biodiversidad, Café Orgánico. 2004. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/conabio_espanol/doctos/Biodiv55.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Caviedes, F.M. Factores que Determinan la Calidad Física y Sensorial del Café. 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.sierraexportadora.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/SSE/448/FACTORES%20QUE%20DETERMINAN%20LA%20CALIDAD%20FISICO%20Y%20SENSORIAL%20EN%20EL%20CAFE.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Mariscal, H.E.I.; Marceleño, F.S.; y Nájera, G.O. Análisis de la cadena productiva del café en el estado de Nayarit, México. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Contab. Econ. Adm. Faccea 2019, 9, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, D.R.; Peterson, A.T. Effects of sample size on accuracy of species distribution models. Ecol. Model. 2002, 148, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.P.; Martınez-Meyer, E. Modeling species’ geographic distributions for preliminary conservation assessments: An implementation with the spiny pocket mice (Heteromys) of Ecuador. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 116, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G.; Raxworthy, C.J.; Nakamura, M.; Townsend, P. Predicting species distributions from small numbers of occurrence records: A test case using cryptic geckos in Madagascar. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 34, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Component | Key | Variable | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Coffe | Coffee presence records (Dependent variable) | Centroids of the areas where there is coffee production | - | |

| Climatic | Temperature | Bio1 | Average annual temperature | Represents the average temperature throughout the year | °C |

| Bio2 | Mean of the diurnal range. Monthly average (max temp–min temp) | Identifies diurnal temperature fluctuations | - | ||

| Bio3 | Isothermality (Bio2/Bio7)(×100) | Describes the magnitude of temperature swings between day and night relative to the annual temperature range | - | ||

| Bio4 | Temperature seasonality (Standard deviation ×100) | Indicates peak periods between temperature ranges | - | ||

| Bio5 | Maximum temperature of the warmest month | Represents the highest temperature in the warmest month | °C | ||

| Bio6 | Minimum temperature of the coldest month | Represents the lowest temperature in the coldest month | °C | ||

| Bio7 | Annual temperature range (Bio5-Bio6) | Shows the ranges of extreme temperature conditions | °C | ||

| Bio8 | Average temperature of the most humid room | Describes the average temperature of the quarter of the year with the highest humidity | °C | ||

| Bio9 | Average temperature of the driest quarter | Indicates the average temperature of the driest quarter of the year | °C | ||

| Bio10 | Average temperature of the warmest room | Describes the average temperature of the warmest quarter of the year | °C | ||

| Bio11 | Average temperature of the coldest room | Represents the average temperature of the coldest quarter of the year | °C | ||

| Precipitation | Bio12 | Annual precipitation | It represents the frequency and amount of rainwater that falls on a specific place throughout the year. | mm | |

| Bio13 | Rainfall of the wettest month | Represents the frequency and amount of rainfall falling on a specific location in the wettest month. | mm | ||

| Bio14 | Rainfall of the driest month | Represents the frequency and amount of rainfall falling on a specific location in the driest month. | mm | ||

| Bio15 | Precipitation seasonality (coefficient of variation) | Indicates periods of precipitation variation | - | ||

| Bio16 | Rainfall from the wettest quarter | Represents the frequency and amount of rainfall falling on a specific location in the wettest month. | mm | ||

| Bio17 | Rainfall of the driest quarter | Describes the amount of precipitation during the driest quarter of the year. | mm | ||

| Bio18 | Precipitation from the warmest quarter | Shows the amount of precipitation during the warmest quarter of the year | mm | ||

| Bio19 | Coldest room precipitation | Characterizes the amount of precipitation during the coldest quarter of the year | mm | ||

| Solar radiation | Bio20 | Solar radiation | Indicates the energy emitted by the sun through space and reaching the ground | kJ/m2/day | |

| Wind | Bio21 | Wind speed | Describes the movement of air | m/s | |

| Humidity | Bio22 | Water vapor pressure | Provides information on the saturation pressure of the water | kPa | |

| Physical | Altitude | Bio23 | Altitude = Digital Elevation Model | Identifies the altitudinal range of the area | - |

| Slope | Bio24 | Slope = Digital Elevation Model | Describe the differences in slope | ||

| Environmental | Vegetation and land use | Bio25 | Coverage and land use | Indicates the different land uses existing in each site | - |

| Floors | Bio26 | Type of soil: Edaphology INEGI | Describes the type and composition of the soil | - |

| Coefficients | Estimate | Std. Error | z Value | Pr (>|z|) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clave | Description | ||||||

| (Intercept) | −5.30 × 102 | 8.31 × 101 | −6.38 | 1.76 × 101 | *** | ||

| 1 | Bio1 | Average annual temperature | −1.35 × 101 | 4.90 × 100 | −2.76 | 5.88 × 10−3 | ** |

| 2 | Bio2 | Mean of the diurnal range. Monthly average (temp max–temp min) | −4.35 × 101 | 5.44 × 100 | −8.00 | 1.20 × 10−15 | *** |

| 3 | Bio3 | Isothermality (Bio2/Bio7) (×100) | 9.24 × 100 | 1.11 × 100 | 8.29 | 2.00 × 10−16 | *** |

| 4 | Bio4 | Temperature seasonality (Standard deviation ×100) | −1.91 × 10−1 | 8.87 × 10−2 | −2.15 | 3.16 × 10−2 | * |

| 5 | Bio10 | Average temperature of the warmest room | −1.14 × 101 | 3.95 × 100 | −2.88 | 3.96 × 10−3 | ** |

| 6 | Bio12 | Annual precipitation | 4.80 × 10−2 | 2.70 × 10−2 | 1.78 | 7.53 × 10−2 | * |

| 7 | Bio14 | Rainfall of the driest month | −1.24 × 100 | 3.64 × 10−1 | −3.41 | 6.59 × 10−4 | *** |

| 8 | Bio17 | Rainfall of the driest quarter | −2.52 × 10−1 | 1.16 × 10−1 | −2.18 | 2.91 × 10−2 | * |

| 9 | Bio18 | Precipitation from the warmest quarter | 5.32 × 10−3 | 1.79 × 10−3 | 2.98 | 2.93 × 10−3 | ** |

| 10 | Bio20 | Solar radiation | 5.52 × 10−3 | 1.90 × 10−3 | 2.90 | 3.71 × 10−3 | ** |

| 11 | Bio21 | Wind speed | −1.33 × 101 | 1.30 × 100 | −10.16 | 2.00 × 10−16 | *** |

| 12 | Bio22 | Water vapor pressure | −6.89 × 101 | 1.13 × 101 | −6.10 | 1.06 × 10−9 | *** |

| 13 | Bio23 | Altitude = Digital Elevation Model | −4.15 × 10−2 | 8.41 × 10−3 | −4.93 | 8.07 × 10−7 | *** |

| Key | Variable | Contribution (%) | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio1 | Average annual temperature | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Bio2 | Mean of the diurnal range. Monthly average (temp max − temp min) | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Bio3 | Isothermality [(Bio2/Bio7) ×100] | 31.6 | 28.3 |

| Bio4 | Temperature seasonality (Standard deviation ×100) | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Bio10 | Average temperature of the warmest room | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Bio12 | Annual precipitation | 1 | 0.4 |

| Bio14 | Rainfall of the driest month | 1 | 0.1 |

| Bio17 | Rainfall of the driest quarter | 8.7 | 4.8 |

| Bio18 | Precipitation from the warmest quarter | 32.9 | 48.6 |

| Bio20 | Solar radiation | 2 | 1.5 |

| Bio21 | Wind speed | 2.3 | 3.2 |

| Bio22 | Water vapor pressure | 6.6 | 10.6 |

| Bio23 | Altitude = Digital Elevation Model | 12.4 | 0.6 |

| Clave | Variable | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Bio1 | Average annual temperature | 20.8–22.2 °C |

| Bio2 | Mean of the diurnal range | 13.9–14.6 °C |

| Bio3 | Isothermality | 68.3–69.2 |

| Bio4 | Temperature seasonality | 245–248 |

| Bio10 | Average temperature of the warmest room | 23–26 °C |

| Bio12 | Annual precipitation | 1250–1350 mm |

| Bio14 | Rainfall of the driest month | 0.5–1.0 mm |

| Bio17 | Rainfall of the driest quarter | 60–80 mm |

| Bio18 | Precipitation from the warmest quarter | 1000–1010 mm |

| Bio20 | Solar radiation | 18,300–18,400 kj/m2/day |

| Bio21 | Wind speed | 1.7–1.9 m/s |

| Bio22 | Water vapor pressure | 1.8–2.0 kPa |

| Bio23 | Altitude | 600–1000 m.a.s.l. |

| No. | Municipality | Municipality Area (km2) | Suitability Surface | Total with Respect to the Municipality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | High | Medium | Low | Very Low | ||||

| 1 | Acaponeta | 1425 | - | 8% (109.56) | - (0.8) | 11% (175.51) | 9% (339.33) | 44% (625.2) |

| 2 | Ahuacatlán | 504 | - | - | - | - | - (0.38) | 0% (0.38) |

| 3 | Amatlán de Cañas | 518 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | Bahía de Banderas | 770 | - | 5% (75.3) | 5% (31.65) | 4% (64.18) | 3% (99.15) | 35% (270.27) |

| 5 | Compostela | 1878 | 27% (149.52) | 24% (323.4) | 22% (135.87) | 16% (260.78) | 9% (348.27) | 65% (1217.84) |

| 6 | Del Nayar | 5139 | 3% (17.25) | 6% (79.74) | 6% (37.32) | 13% (200.01) | 12% (456.41) | 15% (790.72) |

| 7 | Huajicori | 2236 | - | - (3.41) | - | 1% (22.15) | 19% (756.32) | 35% (781.88) |

| 8 | Ixtlán del Río | 493 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 9 | Jala | 503 | - | - | - | - | - (0.01) | 0% (0.01) |

| 10 | La Yesca | 4314 | - | - | - | - (1.36) | 1% (36.85) | 1% (38.2) |

| 11 | Rosamorada | 1767 | - | 15% (200.7) | 6% (35.4) | 10% (153.79) | 8% (299.17) | 39% (689.05) |

| 12 | Ruíz | 520 | 11% (60.37) | 6% (79.46) | 11% (68.23) | 2% (30.18) | 2% (75.87) | 60% (314.11) |

| 13 | San Blas | 1077 | 12% (66.68) | 3% (38.94) | 12% (76.76) | 1% (21.99) | 2% (92.4) | 28% (296.77) |

| 14 | San Pedro Lagunillas | 515 | - | 2% (26.53) | - (0.79) | 7% (110.27) | 7% (269.83) | 79% (407.42) |

| 15 | Santa María del Oro | 1091 | - | - (1.55) | - | 3% (49.82) | 8% (301.06) | 32% (352.43) |

| 16 | Santiago Ixcuintla | 1703 | 7% (38.24) | 2% (21.02) | 7% (46.51) | 1% (23.23) | 8% (330.04) | 27% (459.03) |

| 17 | Tecuala | 987 | - | - | - | - | 1% (30.39) | 3% (30.39) |

| 18 | Tepic | 1634 | 15% (84.33) | 24% (327.61) | 22% (137.17) | 24% (379.49) | 10% (391.1) | 81% (1319.68) |

| 19 | Tuxpan | 310 | - | - (0.77) | - | - (1.37) | 1% (25.92) | 9% (28.05) |

| 20 | Xalisco | 503 | 25% (141.83) | 6% (82.5) | 9% (55.22) | 6% (93.98) | 3% (106.46) | 95% (480) |

| Total, State area | 27,888 | 2% (558.22) | 5% (1370.48) | 2% (625.72) | 6% (1588.1) | 14% (3958.95) | 29% (8101.46) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez, A.A.; Marceleño Flores, S.M.L.; González, O.N.; Vilchez, F.F. Potential Coffee Distribution in a Central-Western Region of Mexico. Ecologies 2023, 4, 269-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies4020018

Jiménez AA, Marceleño Flores SML, González ON, Vilchez FF. Potential Coffee Distribution in a Central-Western Region of Mexico. Ecologies. 2023; 4(2):269-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies4020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez, Armando Avalos, Susana María Lorena Marceleño Flores, Oyolsi Nájera González, and Fernando Flores Vilchez. 2023. "Potential Coffee Distribution in a Central-Western Region of Mexico" Ecologies 4, no. 2: 269-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies4020018

APA StyleJiménez, A. A., Marceleño Flores, S. M. L., González, O. N., & Vilchez, F. F. (2023). Potential Coffee Distribution in a Central-Western Region of Mexico. Ecologies, 4(2), 269-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies4020018