Digital Footprint and Firm Performance: Evidence from Organic and Paid Traffic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

3.2. Models

3.2.1. Panel Regression Models with Fixed Effects

3.2.2. The Generalized Additive Model

4. Findings and Discussions

4.1. Estimates from Panel Fixed Effects Models

4.1.1. Organic Traffic

4.1.2. Paid Traffic

4.2. Discussion

5. Robustness Checks and Tests for Nonlinear Dependencies

5.1. Robustness Checks

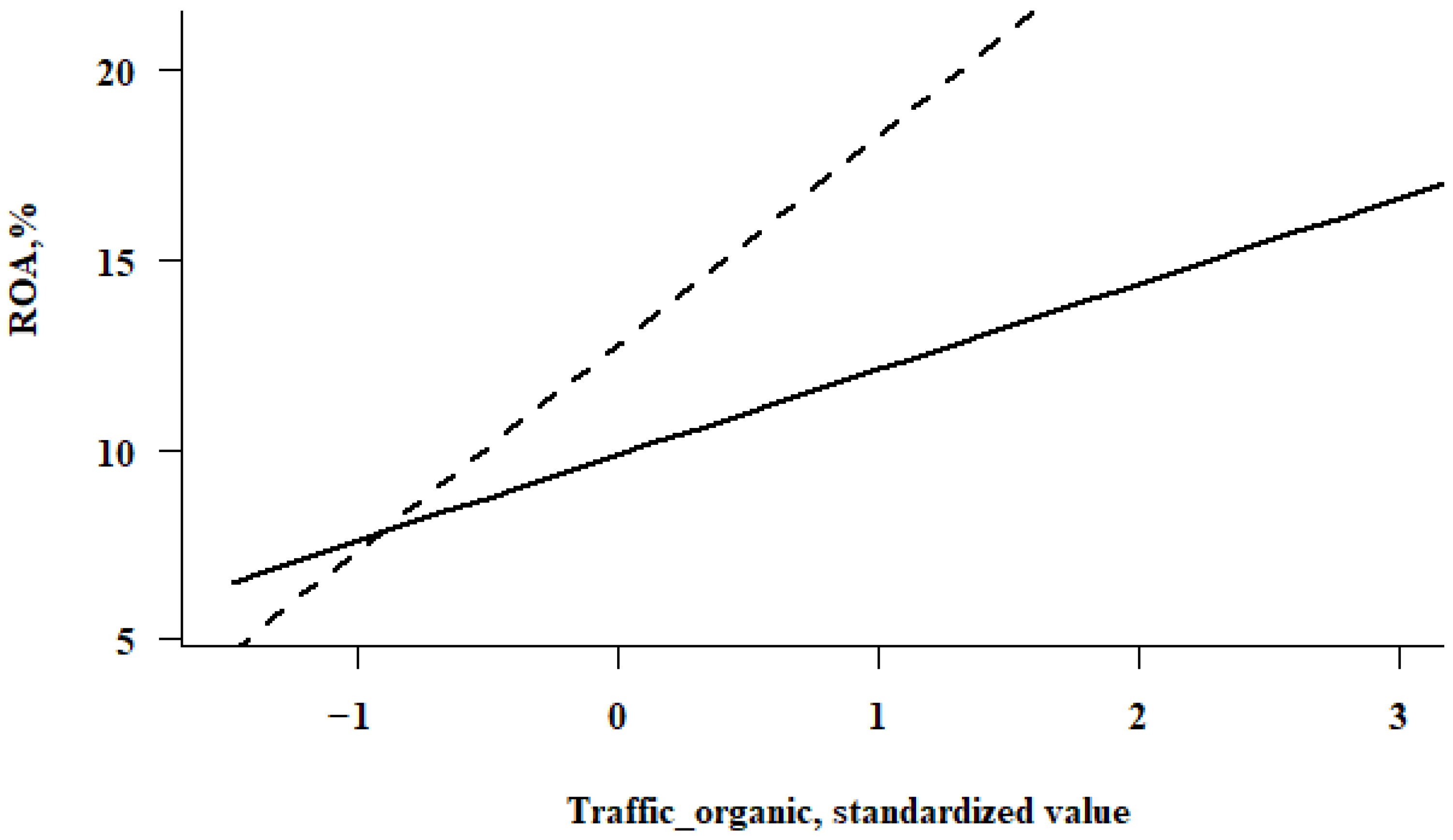

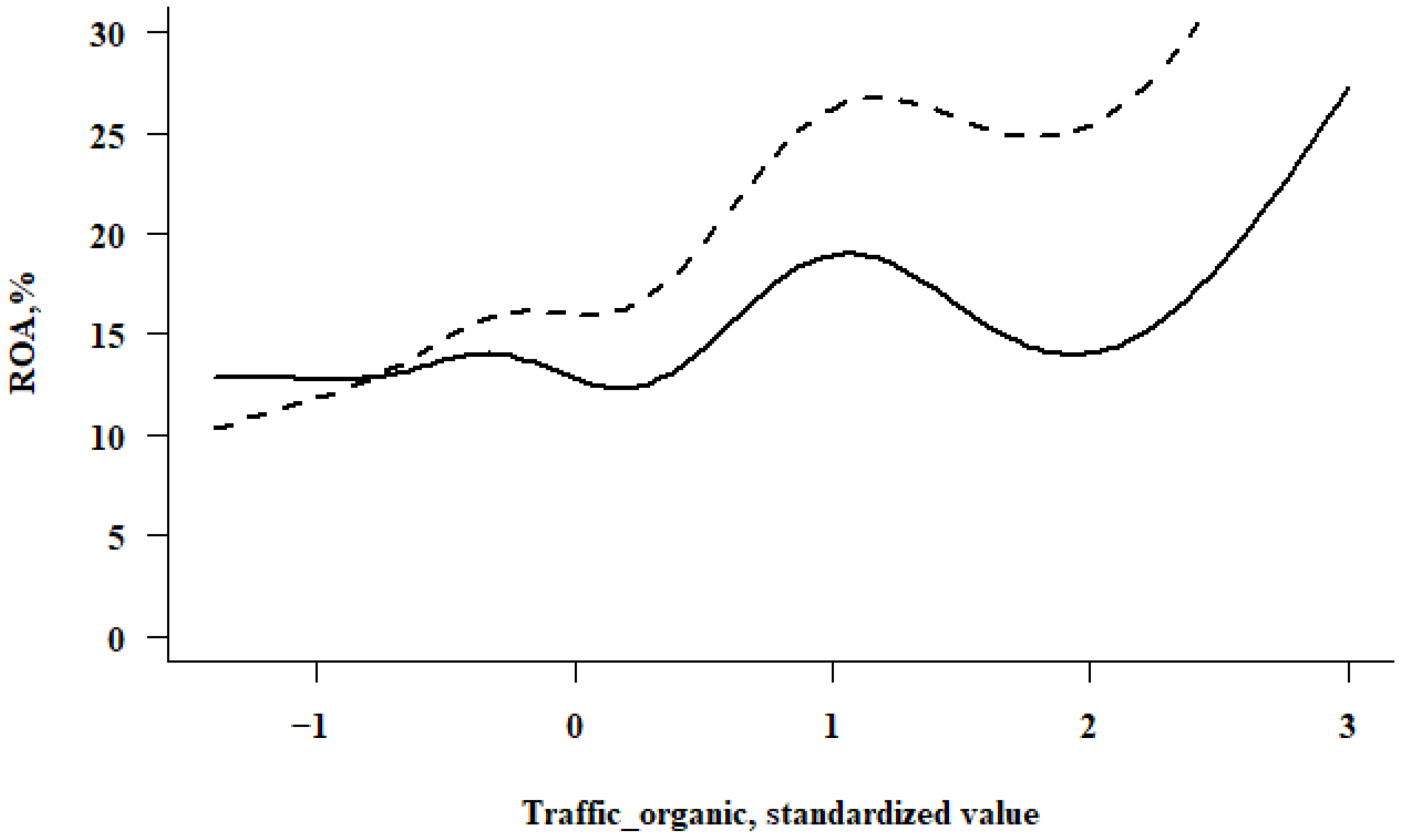

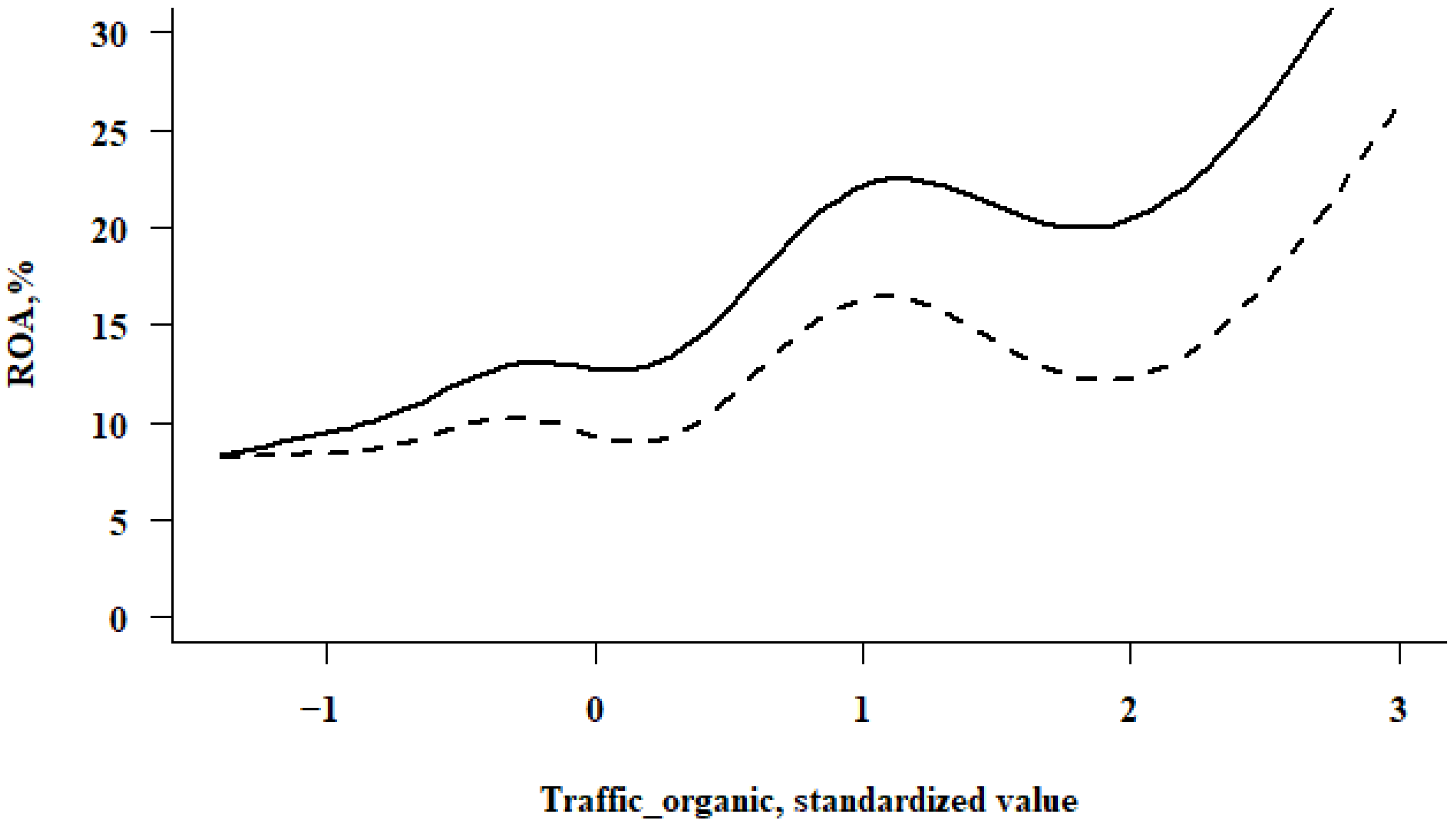

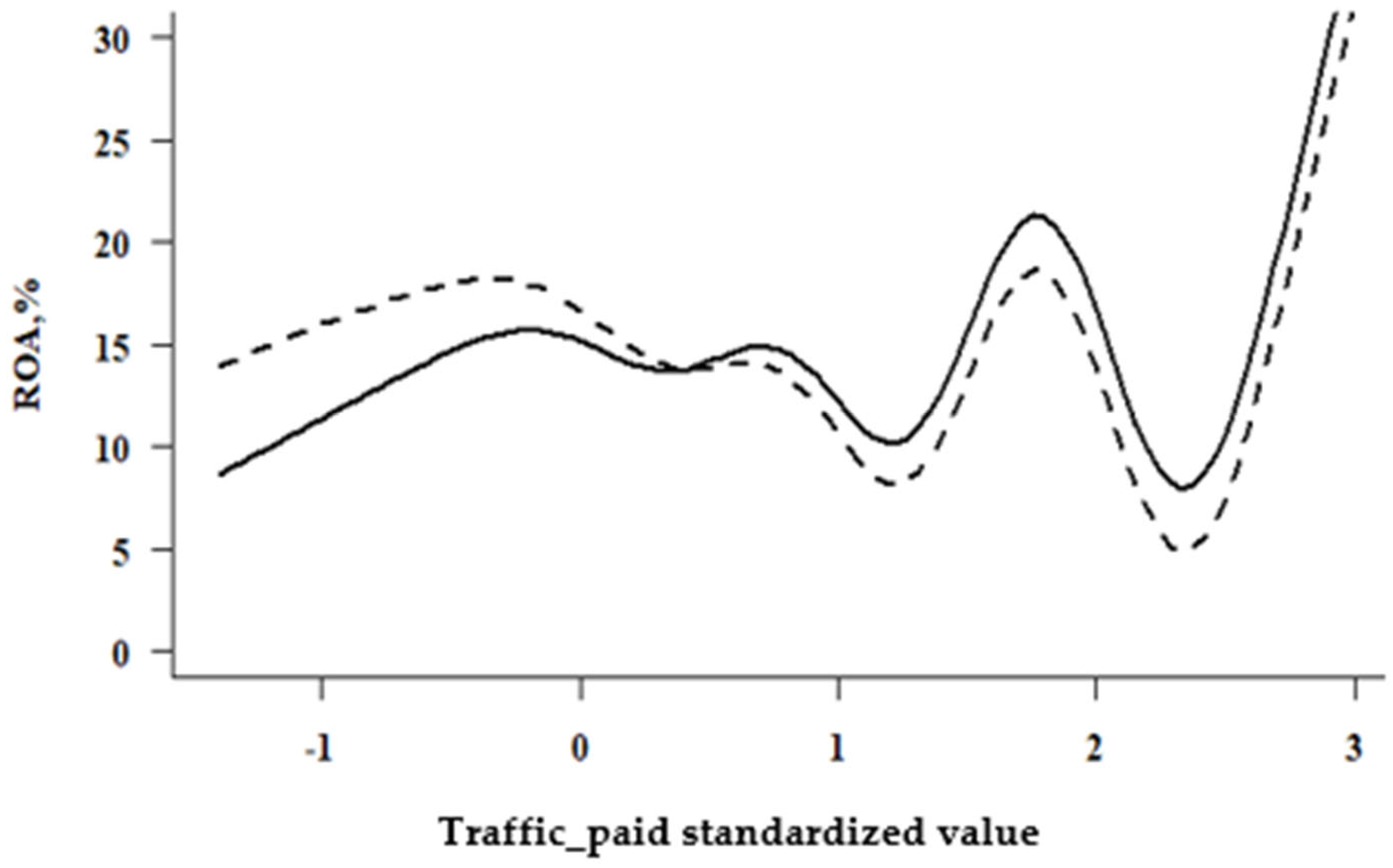

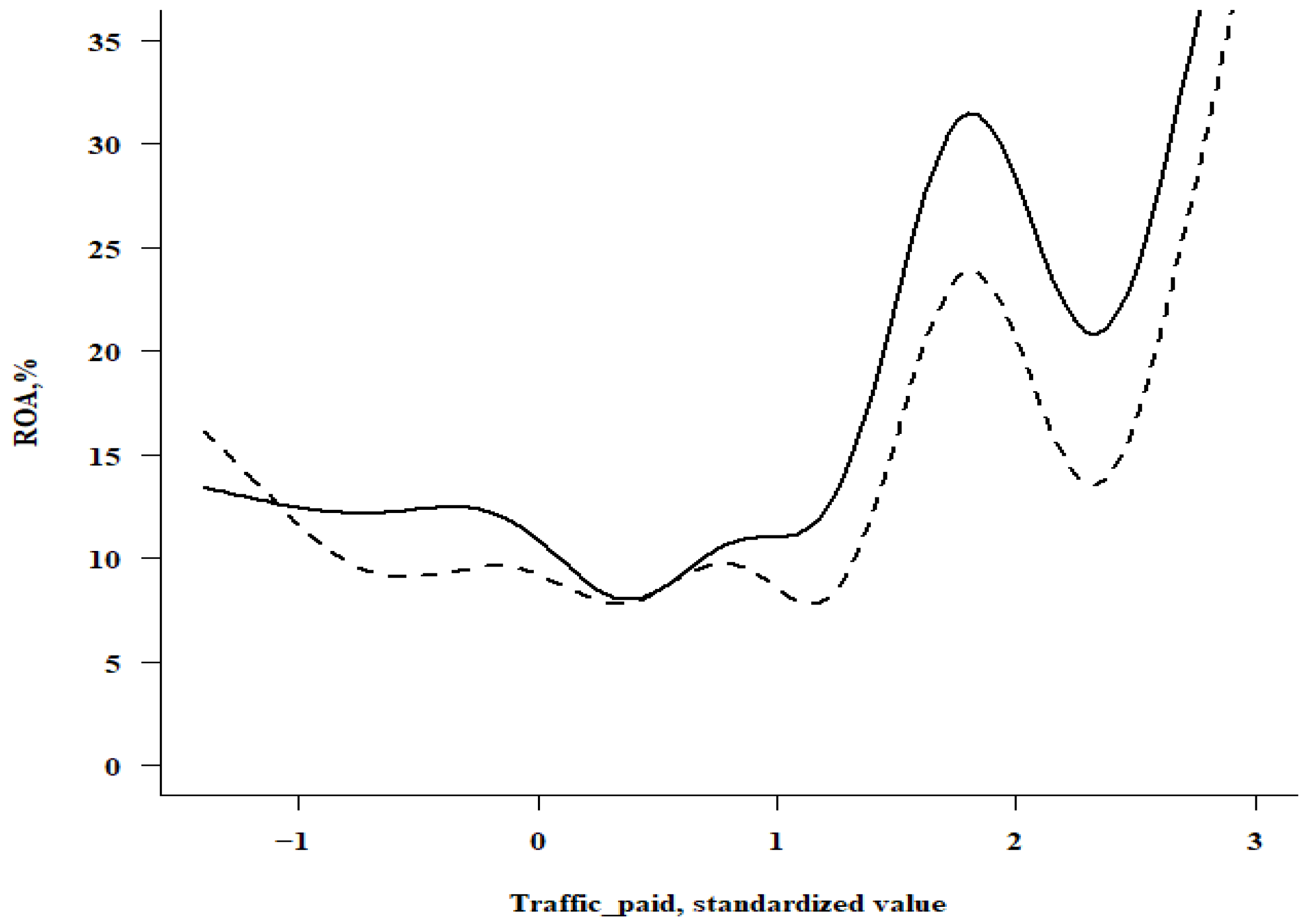

5.2. Tests for Nonlinear Dependencies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2.1 | Model 3.1 | Model 4.1 | Model 5.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth (Sales growth) | 0.9 (0.7) | 0.65 (0.68) | 0.56 (0.68) | 0.64 (0.68) | 0.55 (0.68) |

| Size (Firm size) | −1.26 (0.83) | −3.04 *** (0.87) | −2.09 * (0.92) | −3.12 *** (0.87) | −2.17 * (0.92) |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in total assets) | −1.96 * (0.82) | −1.81 * (0.79) | −2.16 ** (0.8) | −1.75 * (0.8) | −2.1 ** (0.8) |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 6.92 *** (1.48) | 6.89 *** (1.44) | 6.46 *** (1.43) | 6.86 *** (1.44) | 6.43 *** (1.43) |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | −5.08 *** (0.77) | −4.62 *** (0.76) | −4.56 *** (0.75) | −4.65 *** (0.76) | −4.59 *** (0.75) |

| Age (Firm age) | −0.16 (0.75) | −0.17 (0.73) | −0.14 (0.72) | 0.05 (0.77) | 0.08 (0.77) |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 0.7 (0.71) | 0.5 (0.69) | 0.32 (0.69) | 0.53 (0.69) | 0.35 (0.69) |

| Dummy_Industry | −2.65 *** (0.75) | −4.5 *** (0.8) | −4.15 *** (0.8) | −4.4 *** (0.81) | −4.05 *** (0.81) |

| Traffic_organic | 4.25 *** (0.78) | 4.56 *** (0.78) | 4.29 *** (0.78) | 4.6 *** (0.78) | |

| Traffic_organic × Size | −1.85 ** (0.63) | −1.86 ** (0.63) | |||

| Traffic_organic × Age | 0.73 (0.9) | 0.77 (0.89) | |||

| Intercept | 10.38 *** (1.20) | 10.86 *** (1.17) | 11.44 *** (1.18) | 10.89 *** (1.17) | 11.48 *** (1.18) |

| Adj. R2 | 0.220 | 0.268 | 0.281 | 0.268 | 0.281 |

| F-statistic | 17.27 on 8 and 442 DF | 19.6718 on 9 and 441 DF | 18.8907 on 10 and 440 DF | 17.7583 on 10 and 440 DF | 17.2322 on 11 and 439 DF |

| Probability | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2.2 | Model 3.2 | Model 4.2 | Model 5.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth (Sales growth) | 0.9 (0.7) | 0.69 (0.69) | 0.69 (0.69) | 0.68 (0.69) | 0.69 (0.7) |

| Size (Firm size) | −1.26 (0.83) | −1.93 * (0.84) | −1.95 * (0.87) | −1.91 * (0.84) | −1.95 * (0.87) |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in total assets) | −1.96 * (0.82) | −1.96 * (0.81) | −1.95 * (0.81) | −1.98 * (0.81) | −1.97 * (0.82) |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 6.92 *** (1.48) | 7.25 *** (1.46) | 7.25 *** (1.47) | 7.27 *** (1.47) | 7.27 *** (1.47) |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | −5.08 *** (0.77) | −5.15 *** (0.76) | −5.15 *** (0.77) | −5.14 *** (0.77) | −5.14 *** (0.77) |

| Age (Firm age) | −0.16 (0.75) | −0.14 (0.74) | −0.14 (0.74) | −0.19 (0.76) | −0.19 (0.76) |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 0.7 (0.71) | 0.62 (0.7) | 0.63 (0.71) | 0.62 (0.7) | 0.63 (0.71) |

| Dummy_Industry | −2.65 *** (0.75) | −4 *** (0.82) | −4 *** (0.82) | −4.07 *** (0.86) | −4.07 *** (0.86) |

| Traffic_ paid | 2.92 *** (0.78) | 2.9 *** (0.8) | 2.92 *** (0.79) | 2.89 *** (0.81) | |

| Traffic_ paid × Size | 0.07 (0.63) | 0.11 (0.65) | |||

| Traffic_paid × Age | −0.21 (0.82) | −0.24 (0.84) | |||

| Intercept | 10.38 ** (1.20) | 10.46 *** (1.19) | 10.45 *** (1.19) | 10.43 *** (1.19) | 10.41 *** (1.20) |

| Adj. R2 | 0.221 | 0.243 | 0.241 | 0.241 | 0.240 |

| F-statistic | 17.27 on 8 and 442 DF | 17.3421 on 9 and 441 DF | 15.5741 on 10 and 440 DF | 15.5816 on 10 and 440 DF | 14.1361 on 11 and 439 DF |

| Probability | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

References

- Nallasivam, A.; KN, A.S.I.; Desai, K.; Kautish, S.; Ghoshal, S. Universal Access to Internet and Sustainability: Achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. In Digital Technologies to Implement the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaeva, R. Strategic determinants of web site traffic in on-line retailing. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2005, 9, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, G.; Georgiadis, A.G.; Jha, A.K. Establishing the link: Does web traffic from various marketing channels influence direct traffic source purchases? Mark. Lett. 2024, 35, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.; Pentland, A.; Adamic, L.; Aral, S.; Barabási, A.L.; Brewer, D.; Christakis, N.; Contractor, N.; Fowler, J.; Gutmann, M.; et al. Computational social science. Science 2009, 323, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howison, J.; Wiggins, A.; Crowston, K. Validity issues in the use of social network analysis with digital trace data. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debón, A.; Domenech, J. Digital footprint approach for the study of competitiveness in wineries. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 125049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Wielgos, D.M. The value relevance of digital marketing capabilities to firm performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 666–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosamartina, S.; Giustina, S.; Angeloantonio, R. Digital reputation and firm performance: The moderating role of firm orientation towards sustainable development goals (SDGs). J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Srinivasan, S. Going digital: Implications for firm value and performance. Rev. Account. Stud. 2024, 29, 1619–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baye, M.R.; De los Santos, B.; Wildenbeest, M.R. Search engine optimization: What drives organic traffic to retail sites? J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2016, 25, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The foundations of enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadok, R. Toward a synthesis of the resource-based and dynamic-capability views of rent creation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Karjaluoto, H. Digital advertising around paid spaces, E-advertising industry’s revenue engine: A review and research agenda. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Rowe, F.; Branagan, E. Going digital? The impact of social media marketing on retail website traffic, orders and sales. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ghose, A. Analyzing the relationship between organic and sponsored search advertising: Positive, negative, or zero interdependence? Mark. Sci. 2010, 29, 602–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuhua, H.; Larbi-Siaw, O.; Thompson, E.T. Diminishing returns or inverted U? The curvilinear relationship between eco-innovation and firms’ sustainable business performance: The impact of market turbulence. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 4723–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Joinson, A.N. What demographic attributes do our digital footprints reveal? A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, M.; Jansen, N.; Hinz, O. Can We Measure the Structural Dimension of Social Capital with Digital Footprint Data?—An Assessment of the Convergent Validity of an Indicator Extracted from Digital Footprint Data. Schmalenbach J. Bus. Res. 2024, 76, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audia, P.G.; Greve, H.R. Less likely to fail: Low performance, firm size, and factory expansion in the shipbuilding industry. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, C.; Castro, I.; Galán, J.L. Informational networks and innovation in mature industrial clusters. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcombe, A. Organization-creating organizations. Trans-Action 1965, 2, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Ebben, J.; Johnson, A. Bootstrapping in small firms: An empirical analysis of change over time. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Ha, S.; Kim, Y. Innovation ambidexterity, resource configuration and firm growth: Is smallness a liability or an asset? Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 2183–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Fernandez, E.M.; Sandulli, F.D.; Bogers, M. Unpacking liabilities of newness and smallness in innovative start-ups: Investigating the differences in innovation performance between new and older small firms. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.Y.; Joo, M.; Wilbur, K.C. Advertising and brand attitudes: Evidence from 575 brands over five years. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2019, 17, 257–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitsin, V.; Ryzhkova, M.; Vukovic, D.; Anokhin, S. Companies profitability under economic instability: Evidence from the manufacturing industry in Russia. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Shin, B. Conceptualizing digital sanctions as a new type of economic sanctions in the digital era: Digital-related sanctions measures against Russia and their consequences. J. Eurasian Stud. 2025, 16, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; Malesios, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Dey, P.K. Impact of institutional voids on the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Strategy Manag. 2023, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, D.; Rajapakse, A.; Kožuljević, N.; Shukla, Y.S. Search engine optimization (SEO) for digital marketers: Exploring determinants of online search visibility for blood bank service. Online Inf. Rev. 2022, 47, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.R.; Jerath, K.; Katona, Z.; Narayanan, S.; Shin, J.; Wilbur, K.C. Inefficiencies in digital advertising markets. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dong, F. Digital infrastructure construction and corporate innovation efficiency: Evidence from Broadband China Strategy. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Hastie, M.T. Package ‘gam’, R Package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gam/index.html (accessed on 7 December 2025).

| N | Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Correlations (r) and Their Significance (p) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| 1 | Growth | 0.08 | 0.26 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | Size | 22.82 | 1.74 | −0.06 | 1 | |||||||

| 3 | FATA | 17.17 | 17.70 | −0.12 ** | 0.48 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 4 | CACL | 2.78 | 9.92 | 0.03 | −0.16 *** | −0.10 * | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Leverage | 58.86 | 25.67 | 0.03 | 0.14 *** | −0.09 * | −0.27 *** | 1 | ||||

| 6 | Age | 17.95 | 6.62 | −0.01 | 0.22 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.02 | −0.14 *** | 1 | |||

| 7 | Turnover | 198.42 | 91.69 | 0.07 † | 0.07 † | −0.03 | −0.09 * | 0.19 *** | −0.05 | 1 | ||

| 8 | Dummy_ Industry | 0.10 | 0.30 | −0.01 | −0.22 *** | −0.23 *** | 0.09 * | 0.10 * | −0.29 *** | 0.06 | 1 | |

| 9 | Traffic_organic | 10.55 | 2.43 | 0.02 | 0.30 *** | 0.09 * | 0.07 † | −0.01 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.32 *** | 1 |

| 10 | Traffic_paid | 3.16 | 4.59 | 0.03 | 0.14 *** | −0.01 | 0 | 0.09 * | −0.07 † | 0.05 | 0.41 *** | 0.73 *** |

| N | Variables | Model 1 | Model 2.1 | Model 3.1 | Model 4.1 | Model 5.1 | Model 2.2 | Model 3.2 | Model 4.2 | Model 5.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Growth | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | Size | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | FATA | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | CACL | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | Leverage | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | Age | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | Turnover | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | Dummy_ Industry | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 9 | Traffic_organic | + | + | + | + | |||||

| 10 | Traffic_organic × Size | + | + | |||||||

| 11 | Traffic_organic × Age | + | + | |||||||

| 12 | Traffic_ paid | + | + | + | + | |||||

| 13 | Traffic_ paid × Size | + | + | |||||||

| 14 | Traffic_paid × Age | + | + |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2.1 | Model 3.1 | Model 4.1 | Model 5.1 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth (Sales growth) | 1.91 *** (0.56) | 1.77 ** (0.55) | 1.67 ** (0.55) | 1.78 ** (0.55) | 1.68 ** (0.55) | 1.03 |

| Size (Firm size) | −0.86 (0.67) | −2.36 *** (0.71) | −1.46 † (0.76) | −2.42 *** (0.71) | −1.52 * (0.76) | 2.01 |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in to tal assets) | −1.85 ** (0.66) | −1.8 ** (0.64) | −2.08 ** (0.64) | −1.76 ** (0.64) | −2.04 ** (0.65) | 1.43 |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 3.9 *** (0.59) | 3.65 *** (0.58) | 3.43 *** (0.58) | 3.64 *** (0.58) | 3.41 *** (0.58) | 1.14 |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | −6.07 *** (0.61) | −5.73 *** (0.6) | −5.65 *** (0.59) | −5.75 *** (0.6) | −5.67 *** (0.59) | 1.21 |

| Age (Firm age) | −0.17 (0.61) | −0.15 (0.59) | −0.13 (0.59) | −0.05 (0.61) | −0.01 (0.6) | 1.21 |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 1.54 ** (0.57) | 1.42 * (0.56) | 1.27 * (0.56) | 1.44 * (0.56) | 1.29 * (0.56) | 1.06 |

| Dummy_ Industry | −2.18 *** (0.6) | −3.63 *** (0.64) | −3.34 *** (0.65) | −3.57 *** (0.65) | −3.27 *** (0.65) | 1.46 |

| Traffic_organic | 3.54 *** (0.64) | 3.87 *** (0.65) | 3.53 *** (0.64) | 3.86 *** (0.65) | 1.40 | |

| Traffic_organic × Size | −1.61 ** (0.52) | −1.62 ** (0.52) | 1.39 | |||

| Traffic_organic × Age | 0.55 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.7) | 1.08 | |||

| Intercept | 10.40 *** (1.12) | 10.79 *** (1.10) | 11.32 *** (1.10) | 10.80 *** (1.10) | 11.33 *** (1.10) | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.283 | 0.317 | 0.327 | 0.317 | 0.327 | |

| F-statistic | 31.1682 on 8 and 592 DF | 32.456 on 9 and 591 DF | 30.592 on 10 and 590 DF | 29.2518 on 10 and 590 DF | 27.8664 on 11 and 589 DF | |

| Probability | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2.2 | Model 3.2 | Model 4.2 | Model 5.2 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth (Sales growth) | 1.91 *** (0.56) | 1.81 ** (0.56) | 1.83 ** (0.56) | 1.8 ** (0.56) | 1.82 ** (0.56) | 1.03 |

| Size (Firm size) | −0.86 (0.67) | −1.41 * (0.68) | −1.51 * (0.71) | −1.41 * (0.69) | −1.51 * (0.71) | 2.01 |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in total assets) | −1.85 ** (0.66) | −1.82 ** (0.65) | −1.78 ** (0.65) | −1.83 ** (0.66) | −1.79 ** (0.66) | 1.43 |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 3.9 *** (0.59) | 3.9 *** (0.58) | 3.91 *** (0.58) | 3.9 *** (0.58) | 3.91 *** (0.58) | 1.14 |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | −6.07 *** (0.61) | −6.09 *** (0.6) | −6.08 *** (0.6) | −6.08 *** (0.6) | −6.07 *** (0.6) | 1.21 |

| Age (Firm age) | −0.17 (0.61) | −0.18 (0.6) | −0.18 (0.6) | −0.19 (0.61) | −0.2 (0.61) | 1.21 |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 1.54 ** (0.57) | 1.52 ** (0.57) | 1.56 ** (0.57) | 1.52 ** (0.57) | 1.57 ** (0.57) | 1.06 |

| Dummy_Industry | −2.18 *** (0.6) | −3.18 *** (0.66) | −3.17 *** (0.66) | −3.2 *** (0.69) | −3.21 *** (0.69) | 1.46 |

| Traffic_ paid | 2.18 *** (0.63) | 2.09 ** (0.64) | 2.18 *** (0.63) | 2.1 ** (0.65) | 1.36 | |

| Traffic_ paid × Size | 0.28 (0.51) | 0.3 (0.52) | 1.24 | |||

| Traffic_paid × Age | −0.05 (0.65) | −0.12 (0.66) | 1.16 | |||

| Intercept | 10.40 *** (1.12) | 10.44 *** (1.11) | 10.39 *** (1.11) | 10.43 *** (1.12) | 10.37 *** (1.12) | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.283 | 0.296 | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.295 | |

| F-statistic | 31.1682 on 8 and 592 DF | 29.5629 on 9 and 591 DF | 26.6071 on 10 and 590 DF | 26.5623 on 10 and 590 DF | 24.1517 on 11 and 589 DF | |

| Probability | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Variables | ROA t Model 5.1 | ROA t + 1 Model 5.1 | ROA t Model 5.2 | ROA t + 1 Model 5.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth (Sales growth) | 1.68 ** (0.55) | 0.55 (0.72) | 1.82 ** (0.57) | 0.69 (0.74) |

| Size (Firm size) | −1.52 * (0.77) | −2.17 * (0.97) | −1.51 * (0.72) | −1.95 * (0.91) |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in total assets) | −2.04 ** (0.65) | −2.1 * (0.84) | −1.79 ** (0.67) | −1.97 * (0.86) |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 3.41 *** (0.62) | 6.43 *** (1.55) | 3.91 *** (0.62) | 7.27 *** (1.60) |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | −5.67 *** (0.60) | −4.59 *** (0.79) | −6.07 *** (0.61) | −5.14 *** (0.81) |

| Age (Firm age) | −0.01 (0.61) | 0.08 (0.80) | −0.2 (0.62) | −0.19 (0.80) |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 1.29 * (0.56) | 0.35 (0.73) | 1.57 ** (0.58) | 0.63 (0.75) |

| Dummy_Industry | −3.27 *** (0.66) | −4.05 *** (0.85) | −3.21 *** (0.70) | −4.07 *** (0.91) |

| Traffic_organic (Traffic_paid) | 3.86 *** (0.65) | 4.6 *** (0.82) | 2.1 ** (0.65) | 2.89 *** (0.85) |

| Traffic_organic × Size (Traffic_paid × Size) | −1.62 ** (0.52) | −1.86 ** (0.66) | 0.3 (0.53) | 0.11 (0.68) |

| Traffic_organic × Age (Traffic_paid × Age) | 0.6 (0.71) | 0.77 (0.94) | −0.12 (0.67) | −0.24 (0.88) |

| Intercept | 11.33 *** (1.10) | 11.48 *** (1.18) | 10.37 *** (1.12) | 10.41 *** (1.20) |

| Adj. R2 | 0.327 | 0.281 | 0.295 | 0.240 |

| F-statistic | 27.8664 on 11 and 589 DF | 17.2322 on 11 and 439 DF | 24.1517 on 11 and 589 DF | 14.1361 on 11 and 439 DF |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Variables | OrganicTraffic ~ PaidTraffic + Growth + Size + FATA + CACL + Leverage + Age + Turnover + Dummy_Industry | ivreg(ROA ~ OrganicTraffic + Growth + Size + FATA + CACL + Leverage + Age + Turnover + Dummy_Industry | PaidTraffic + Growth + Size + FATA + CACL + Leverage + Age + Turnover + Dummy_Industry) |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic_organic | 3.32 ** (1.27) | |

| PaidTraffic | 0.66 *** (0.03) | |

| Growth (Sales growth) | 0.01 (0.03) | 1.78 ** (0.63) |

| Size (Firm size) | 0.258 *** (0.03) | −2.27 ** (0.73) |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in to tal assets) | 0.00 (0.03) | −1.80 ** (0.57) |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 0.07 ** (0.03) | 3.67 *** (0.91) |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | −0.10 *** (0.03) | −5.75 *** (0.66) |

| Age (Firm age) | −0.01 (0.03) | −0.20 (0.55) |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 0.03 (0.03) | 1.43 ** (0.53) |

| Dummy_ Industry | 0.11 *** (0.03) | −3.55 *** (0.75) |

| Intercept | −0.10 † (0.05) | 10.41 *** (0.54) |

| Adj. R2 | 0.602 | 0.321 |

| F-statistic/Wald test: | 102.766 on 9 and 591 DF | Wald test: 14.17 on 9 and 594 DF |

| Probability | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diagnostic test | ||

| Weak instruments | <() *** | |

| Wu–Hausman | 0.832 | |

| Variables | Model 5.1 Traffic_Organic | Model 5.2 Traffic_Paid |

|---|---|---|

| Growth (Sales growth) | 4.74 ** (5.88) | 3.75 ** (4.73) |

| Size (Firm size) | 1.00 * (1.00) | 1.00 (1.00) |

| FATA (Share of fixed assets in total assets) | 2.79 *** (3.48) | 2.84 ** (3.54) |

| CACL (Current liquidity ratio) | 8.62 *** (8.95) | 8.76 *** (8.98) |

| Leverage (Total debt in assets) | 8.54 *** (8.93) | 8.55 *** (8.93) |

| Age (Firm age) | 4.35 ** (5.38) | 4.55 * (5.62) |

| Turnover (Asset turnover) | 2.80 *** (3.52) | 2.81 *** (3.53) |

| Dummy_Industry | −2.86 *** (0.64) | −1.64 * (0.74) |

| Traffic_organic (Traffic_paid) | 6.62 *** (7.76) | 7.89 * (8.64) |

| Traffic_organic × Size (Traffic_paid × Size) | 1.00 *** (1.00) | 2.66 λ (3.43) |

| Traffic_organic × Age (Traffic_paid × Age) | 1.00 λ (1.00) | 5.83 * (6.99) |

| Intercept | 10.41 *** (0.47) | 10.41 *** (0.47) |

| Adj. R2 | 0.495 | 0.500 |

| Deviance explained | 53.1% | 54.1% |

| GCV | 142.18 | 142.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vukovic, D.B.; Spitsina, L.; Spitsin, V.; Lyzin, I.; Maiti, M. Digital Footprint and Firm Performance: Evidence from Organic and Paid Traffic. World 2026, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/world7010011

Vukovic DB, Spitsina L, Spitsin V, Lyzin I, Maiti M. Digital Footprint and Firm Performance: Evidence from Organic and Paid Traffic. World. 2026; 7(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/world7010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleVukovic, Darko B., Lubov Spitsina, Vladislav Spitsin, Ivan Lyzin, and Moinak Maiti. 2026. "Digital Footprint and Firm Performance: Evidence from Organic and Paid Traffic" World 7, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/world7010011

APA StyleVukovic, D. B., Spitsina, L., Spitsin, V., Lyzin, I., & Maiti, M. (2026). Digital Footprint and Firm Performance: Evidence from Organic and Paid Traffic. World, 7(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/world7010011