1. Introduction

There is a focus on lifelong learning and adult education in the political documents stimulated by the accelerating digital transformation, which requires the acquiring of new skills. One-fifth of the funds in the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will be invested in digital transformation, with funds dedicated, among others, to the development of digital skills [

1]. Similarly, Next Generation EU has been investing in a series of critical areas; these include green transition, digital transformation, social and territorial cohesion, policies for the next generation, and smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth. The promise is to make the next ten years Europe’s Digital Decade. The goals are to provide EU funding for online training courses so that “everyone, young or old” can improve their digital skills to help “small and medium-sized businesses go online” and to make e-education more accessible. The Digital Decade Policy Program (2021–2030) emphasizes the importance of education and training to bring tangible career incentives and reduce differences in opportunities and treatment between women and men. In the same program, artificial intelligence literacy is defined as strategic for employability, competitiveness, and active citizenship [

2]. The Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act (2021–2024) indirectly promotes AI skills as being social, not only technical skills [

3]. Regulations and policy efforts for reducing societal risks by using AI occur together with the process of digitalization. The political goal is for “improving existing skills (up-skilling) and training in new skills (re-skilling) as well as life-long learning by the active population, in order to ensure that full advantage is taken of the opportunities of the digitalization of industry and services” (Art. 12, Digital Decade Policy Programme 2030) [

2].

The social problem is that workers’ preferences do not favor retraining; instead, workers seek to receive governmental and trade union support for protectionist policies [

1]. There is a discrepancy between political goals for increasing participation in continuing training and individuals’ expectations for support in the process of digitalization. Opportunities for adult education are increasing with the growing availability of free online courses. However, the working class and small business owners (both men and women) who are at risk of declining employability due to relatively underdeveloped digital skills may face structural barriers (limited resources and availability of courses offered by employers or by governmental programs) or struggle for individual reasons, such as a lack of motivation to take advantage of existing training opportunities. The sociological problem is the reproduction of social inequalities between occupational classes and genders in the process of digitalization. This is related to the ongoing academic debate on the impact of digitalization on social inequalities. Scholars give arguments supporting two main perspectives: one emphasizes reproduction effects, while the other emphasizes the transformative effects of digitalization.

The research gap lies in the need to investigate digital performance and income inequality as factors at the macro level, which are associated with participation in adult education considering occupational classes and gender. The relationship between the ongoing digitalization process and existing social inequalities based on the intersection of occupational class and gender is relatively under-investigated. Within the adult education literature, one research gap concerns the study of the effects of digital performance at the country level on the inequalities between occupational groups for individual take-up of additional training. The challenge is as follows: How to avoid the accumulation of digital inequalities with the existing social inequalities based on occupational class and gender in the field of adult education? Both occupational class and gender represent different types of inequalities: economic, expressed in insufficient material resources, and cultural, including resistance to change, predetermined roles, and prejudices that reproduce injustice between genders, classes, and ethnicities [

4].

The COVID-19 crisis has made almost all small businesses more reliant on technology. More than a third (43%) anticipated that 11–30% of their business would be digital by 2021, while nearly the same proportion (45%) expected even higher levels of digitalization [

5]. The three main challenges of digitalization for small businesses, however, are a shortage of digital skills, cultural resistance to change, and limited budgets (ibid.).

The ongoing need for up-skilling and re-skilling during the digital transformation may be more effectively addressed through participation in online courses. Digitalization offers better opportunities for free online courses available anytime. Adult education may take different forms—formal, non-formal, and informal [

6]—although recent studies emphasize that these concepts are difficult to compare and measure cross-nationally because their structural relationships vary across countries [

7,

8]. Thus, adult learning and education has a hybrid character [

9], which often results in “intangible conceptual tensions” ([

10], p. 1) and is heterogenous even within a separate form. It can be job-related or non-job-related. It can be provided in-person or online and can be either paid or free. When paid, the courses may be funded by individuals, employers, or public programs. The question of who pays for the additional training is especially important when considering the needs of more vulnerable groups from a social investment perspective. The social investment perspective [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] emphasizes the necessity to invest in, mobilize, and renew human capital and human capabilities along the entire life course to address social risks. The core idea is to prepare rather than repair, that is, to equip individuals ex ante with the skills and education needed to cope with risks over the life course, rather than to merely compensate for the incidence of such risk ex post [

16]. Evidence for the proficiency of social investment policies is boosting employment while mitigating poverty. Continental and Nordic European countries have succeeded in achieving the world’s highest levels of reconciliation of employment with relatively low levels of inequality. They are better prepared for the future, creating knowledge-intensive jobs with low polarization. However, this does not apply to all European welfare states. Southern European countries fall below objectives for both high employment and low inequality levels [

17]. We aim to investigate the impact of inequality on participation in adult education at the country level.

Against this background, the aim is to analyze digital performance as an indicator at the macro level of the effects of participation in adult education among lower social classes and women. We test whether higher Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) scores lead to a decrease in social inequalities between occupational classes and between men and women in European countries with different levels of digitalization. As of 2023, in line with the Digital Decade report, in which DESI is integrated, EU countries have been advancing in their digitalization but still struggle to close the gaps in digital skills, the digital transformation of SMEs, and the rollout of advanced 5G networks.

We are interested in investigating the relation between individuals and digital society and consider both individual-level characteristics—occupational class and gender—and country-level characteristics, namely digitalization as measured by the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) and the level of income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient. The indicators for participation in adult education and socio-economic and socio-demographic inequalities are at the individual level (education, employment status, income, social origin, gender, age, and place of residence). A higher DESI index at the macro level may be positively associated with, and contribute to higher participation in, additional work-related training. We further test whether higher DESI scores also lead to a decrease in inequalities based on class and gender. Thus, this article addresses the following research questions:

Which individual characteristics are associated with a higher chance of people 25–64-years-old participating in non-formal job-related adult learning in the previous 12 months?

What is the association of DESI and the Gini coefficient as macro-level indicators for the likelihood of participation in non-formal job-related adult learning?

Are there any cross-level interaction effects between DESI and gender or between DESI and class, respectively?

2. Review of the Relevant Literature

The theoretical framework of the paper links together digitalization and its effects on existing social inequalities, the intersection between occupational class and gender, and their impact on participation in adult education. We take the differences based on gender as a main factor together with occupational class for unequal access to adult education. Age, educational attainment, social origin, income, and place of residence are analyzed as important individual-level characteristics. We perform a micro–macro analysis of access to the internet for participation in adult education for occupational classes and for men and women in European countries with different levels of digitalization and income inequality.

According to the reproduction perspective, the arguments can be summarized with the Matthew effect, where resources are distributed among individuals based on how much they already have. This results in low-ranked individuals increasingly struggling to improve their social positions over time due to having fewer resources to invest. Conversely, high-ranked individuals find it easier to preserve their positions and maintain their family’s social status. Moreover, the human capital of those who choose technologies remains unchanged [

18]. The transformative perspective is formulated with different terms such as diversification [

19] or “evolutionary approach” in the recently published

“Compendium of Digital Sociology”. The term is used to reflect trends in the development of sociology through interdisciplinary cooperation with mass communication and computer sciences, at both the theoretical and methodological levels [

20].

The relationship between the ongoing digitalization process and existing social inequalities requires deeper understanding and investigation. The concept of the three-level digital divide points to access to internet, the acquisition of digital skills, and the benefits derived from using the internet. The first level means inclusion of someone in a digital society with basic digital skills and an environment that enables access. There is a wide acceptance of the understanding that access to the internet for the majority of the population in economically developed countries is more or less an achieved goal. However, statistical data and empirical research show that unequal access to the internet remains an issue for some social groups based on poverty or place of residence. Limited access to the internet in small locations and villages in poor ethnic neighborhoods remains because development of the internet infrastructure is not economically effective. This is why it is necessary to study different life situations that hinder access to and use of digital technologies [

21].

The second level points to equality: the improvement of skills and opportunities so that their skills are comparable across different social groups. However, findings from previous research show that gender and occupational class equality is not observed in the three indicators for the obtained computer and internet functionalities analyzed based on data from the European Social Survey. All classes have lower digital skills compared with the service class and men have higher skills compared to women [

22].

The third level is described in the literature with the term “efficiency”—the autonomy to use the skills and opportunities they have to do what they want and need [

23]. Access, acquisition of digital skills, and the ability to take advantage of digital technologies depends on economic status [

24], occupational status (class), country, region, and degree of urbanization of the settlement, as well as on gender, age, and ethnicity.

Social inequalities arise in relation to digital skills for autonomous use of the internet and digital technologies. The motives and purposes for using the internet—whether educational or market-oriented—also depend on an individual’s social status. The third level of the digital divide (and inclusion) can be considered in parallel with the existing processes of social differentiation and stratification in society, as it encompasses the previous two levels. The online and offline benefits are different for people occupying stratified positions in the social structure in terms of improving life trajectories and increasing their market opportunities [

25]. The digital divide and social inequalities—socio-economic (inequalities between occupational groups with various levels of education and job-related need of usage of digital technologies) and socio-demographic inequalities (by gender)—are in a state of mutual influence.

Socio-economic, socio-demographic, and inequalities based on place of living are reflected in online outcomes of internet use, which are transformed into digital inequalities and feed back into social inequalities through unequal benefits for different categories of online users. A recent study shows that in Germany, the gender gap in digital literacy emerges as early as upper secondary education and persists across adult cohorts—although it is smaller among those working or studying in STEM fields [

26].

People’s higher social status also makes them more privileged online users with real offline benefits for themselves [

27]. Digital inequalities that arose during the COVID-19 lockdown in learning opportunities have been studied in five developing countries in Asia—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Afghanistan. The authors found that large population segments lack access to internet services and that woman are ranked lower in terms of access. In addition, women face discriminatory gendered rules connected to household care responsibilities. To explain the digital divide in developing countries, the authors proposed an analytical perspective that encompasses structure, culture, and agency [

28]. It is also worth mentioning that previous research has identified that digitalization and technological advancement bring risks of exclusion, skills obsolescence, and unequal distribution of benefits [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The theoretical model linking the digital divide with gender inequalities and injustice in developing countries is comparable with the socio-economic, socio-demographic (cultural), and residential inequalities proposed in the present paper. For future research of gender inequalities related to the digital divide, it is worth using the proposed five-element construct—communities, time, location, social context, and sites of practice. The five-element construct is worthy of further qualitative research on gender inequalities related to the digital divide. This article, however, aims to contribute to the research efforts to bridge the digital gap using quantitative data, emphasizing that it is essential to understand and monitor the extent of this gap worldwide [

33]. We analyze participation in adult education for occupational classes and for men and women in European countries with different levels of digitalization and income inequality. The critical message from previous research is that the social embeddedness of adult education should be considered [

34].

Among the various analytical perspectives, we focus on the effects of digitalization in a given country on individuals’ chances of taking additional training in the previous year, which is job-related. Analyses of adult education gain more complexity with a focus set on class patterns, strategies, and transitions, e.g., [

35,

36]. Individual-level characteristics lead also to higher vulnerability based on gender, age, low educational attainment, or ethnic minority status [

37]. Non-traditional students, who follow different strategies for returning to education in later life, can potentially benefit from online preparatory courses [

38].

The focus of this paper is on the adult population, and we also compare the participation in learning of those who are in paid work with those who are inactive or unemployed. Previous research suggests unequal preparation, motivation, and readiness for the digital economy across different occupational groups [

39]. Others explain that interest in occupations prevails over interest in gender [

40]. We believe that both occupational class and gender deserve greater attention, as they reveal considerable inequalities in participation in adult education in the process of ongoing digitalization because of gendered-based occupational segregation.

Occupational classes are gendered based on the distribution of individuals by occupation and gender. This gender occupational segregation has been monitored by the Duncan index. The Duncan index describes the percentage of workers who would need to switch jobs to obtain an equal distribution of men and women in each job type. A Duncan index that is closer to zero indicates a more similar distribution of men and women across employment categories [

41]. According to this index, less than 20% of employees are female among drivers, electrical trade workers, and building trade workers. More than 60% of employees are female among health associate professionals, cleaners and helpers, and teaching professionals [

41] (p. 3). There are more men among the working class and more women are in the service classes. That means that exposure to digitalization and motivation towards additional training may be different for men and women depending on their occupational position.

The decline of the working class, driven by skill-based technological change, and the fact that the working class is seen as a “great absentee from the public debate” [

42] provide strong arguments for examining the impact of digitalization on individuals’ life chances from a class perspective. The trends of a declining working class and the rise of the middle class have been observed since the end of the 20th century. The three components of the salaried middle class—managers, technical experts, and social-cultural professionals—expanded their share in the employment structure, while the working class declined. Within the working class, the decline is primarily among production workers in “technical work logic”, such as craft workers, machine operators, and farmhands, while service workers in “interpersonal work logic”, such as waiters, sales assistants, and nursing aids have not experienced the same decline ([

42], p. 10), [

43]. Manual workers are identified as one of the vulnerable groups who evaluate themselves as having meager digital skills, are afraid that robots could steal their jobs, and have low usage of the internet [

44].

Research on the simultaneous effects of occupational class and gender for taking part in additional training takes theoretical and methodological foundations from the intersectional approach with a focus on multiple categories of inequality and exclusion and their negative effects on individuals. Leslie McCall [

45] (p. 1773) has differentiated between “intra-categorical” research, focusing on a particular social group at neglected points of intersection, and “inter-categorial” research comparing different social groups. Sylvia Walby [

46] addresses intersectionality within her complex theory. This theory criticizes focusing only on one dimension of inequality or one structural category. It is important that complexity is considered and that disadvantages caused by different mechanisms of exclusion can be uncovered [

47]. From the perspective of the intersectional approach, we analyze the effects of digital performance at the country level within the occupational classes on the individual-level choice to take part in adult education. First, we analyze gender inequality between men and women in participation in adult education controlling for occupational class and digital performance (inter-categorial research). Then, we analyze within each of the categories (intra-categorial research)—separately for men and women—the effects of digitalization on the occupational classes with the lowest prospect of participating in adult education; these are the lower service class for women and the lower working class and small business owners for men.

The major change of gender roles is a fact; however, gender inequalities in the digital domain remain. According to the Gender Equality Index [

48], the segregation of women and men in education and work is substantial. The remaining gender gaps in the digital domain point to the need to study equality of outcomes, in addition to equality of opportunities. Equality of outcomes takes into account that individuals may face different obstacles in utilizing the opportunities they have [

4]. Sex segregation in education contributes to the reproduction of gender inequalities regarding the choice of occupation [

49]. Further, occupational gender segregation is an important mechanism which accounts for the reproduction of gender inequalities in the digital domain because of the gender-specific labor processes and occupation of jobs that require the use of technology [

50]. Moreover, occupational sex segregation has important consequences for the life trajectories and life chances of men and women, in particular for the reproduction of income inequalities [

51]. Gender-typical life plans are also part of inequality mechanisms and processes.

The intersection between occupation and gender is important to study in the context of the ongoing debate as to whether the technological change and the tendency of upgrading of occupational skills or of polarization occurring on the labor market are happening in countries with different levels of digitalization. The employment share of medium-skilled occupations declined in many countries between 2006 and 2016. Southern and Eastern European countries (Greece, Cyprus, Croatia, and Latvia) have the sharpest decline of medium-skilled occupations. The share of women increased substantially among professionals, service, and sales workers. At the same time, women declined in occupations of technicians, craft workers, and elementary occupations [

52]. We apply a micro–macro approach which allows us to investigate differences between European countries in considering the effects of digitalization as a country mechanism for mitigating inequalities based on class and gender. The macro perspective is important, considering that life chances are embedded in institutional and cultural contexts that allow the use of individual resources in a class- and gender-specific way.

Previous research indicates that participation in lifelong learning is heavily influenced by social class and gender (e.g., [

53]). In more recent years, increasing attention has been given to how these factors intersect, uncovering significant inequalities in access to and participation in lifelong education [

54]. However, to the best of our knowledge, we did not find studies that show how these relationships are moderated by digitalization.

The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) monitors the overall digital performance of EU countries regarding their digital competitiveness. It summarizes indicators that the European Commission has reported since 2014. The indicators are human capital development, connectivity, integration of digital technology, and inclusion in digital public services. These indicators cover the three levels of the digital divide—access, skills, and benefits—regarding inclusion in online activities. According to DESI (2022), the use of online courses takes the penultimate position with an average of 16% of the population in EU countries among eight different online activities. The highest share is seen for playing games, downloading films, music—71.3%. The lowest share is seen for enterprises using e-commerce marketplaces for sales—8.6%.

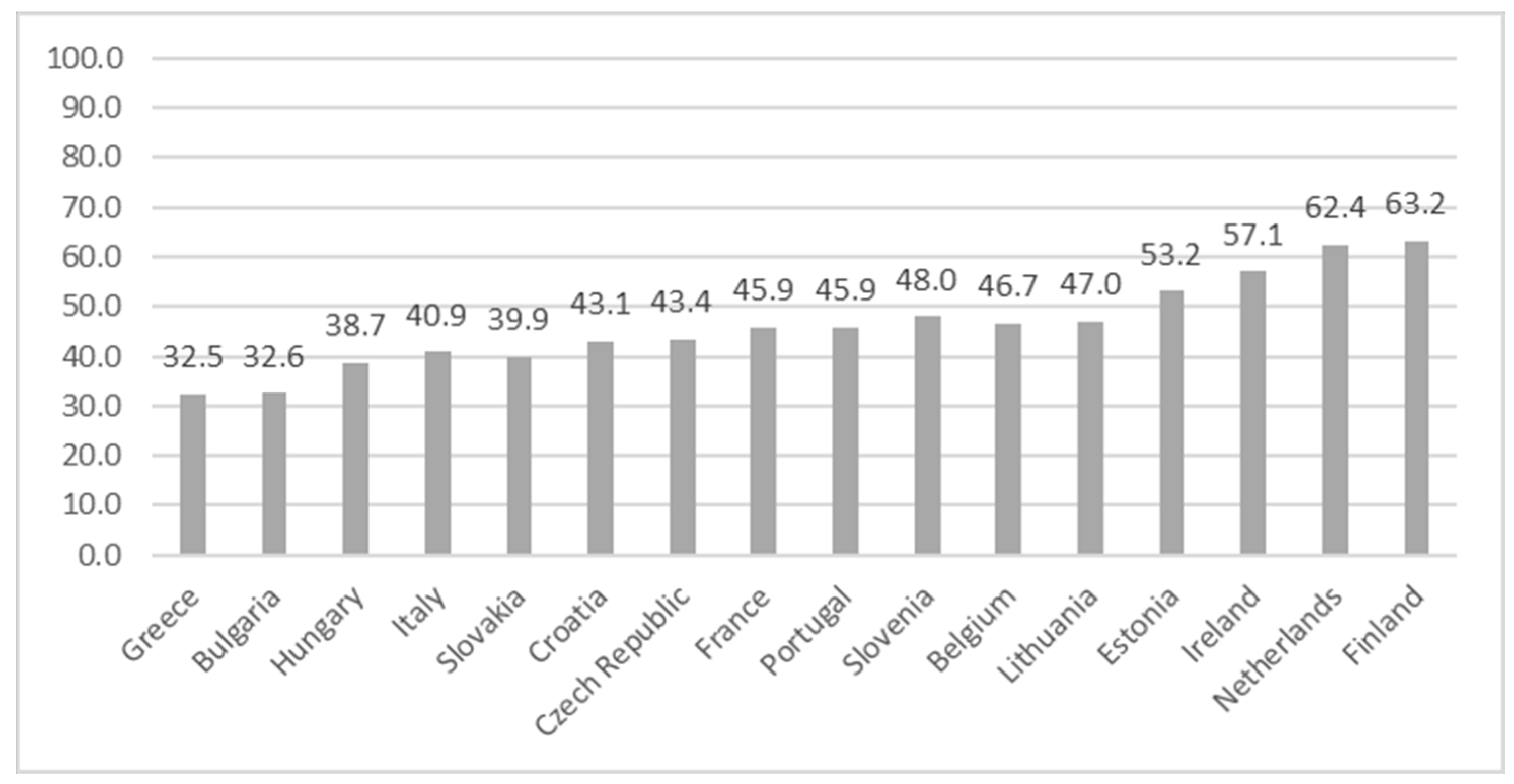

The differences between European countries measured by the DESI are substantial (

Figure 1). The literature identifies four clusters of European countries according to their digital performance: “digitalization leaders and strong, moderate, and modest digitalizators” [

55]. Country performance could be different in the separate indicators. For example, high scores on the human capital indicator concerning the representation of women in STEM disciplines and among ICT specialists often coincide with the low average DESI score in the share of people taking online courses. The low participation in online courses in some European countries and the inequality of the opportunities offered by digital transformation to raise skills justify the need of the present analysis.

The second macro-level indicator used in the analysis is the Gini coefficient, measuring the income gap in a country. The employment change in the different income quintiles is important for the analysis of the processes of upgrading and polarization [

56]. While upgrading of the occupational structure is the dominant pattern in Europe in the last decade, leading to an increase in middle incomes, polarization has been identified for others. Among other reasons, the decrease in incomes in the first and third quintiles has been explained by high income inequality—decreasing shares of manufacturing and increasing shares of IT industry and professional services—a decline in the middle-income segment, and upgrading at the top of the income structure. Differences in the level of income inequality in EU countries, measured by the Gini coefficient, ranged from 30.1 (EU-27 average) to 39.7 (Bulgaria) in 2021 [

57].

Policies supporting education and training over the life course aim to prepare individuals to avoid unemployment and living in poverty within the social investment perspective. Anton Hemerijck (2017) defines three functions of the social investment policies: (1) raising the quality of education and training with the aim of maintaining the “stock of human capital”; (2) easing labor and life course transitions, facilitating the “work–life balance flows”; (3) income protection and economic stabilization through “inclusion buffers” [

58]. This paper is related to the “stock of human capital” and to the efficiency of the “inclusion buffers”. How effective the country policies are for mitigating the inequalities between occupational classes by avoiding job polarization and income inequalities will be evaluated through one of the possible outcomes of participation in adult learning.

3. Methodology Employed and Data Used

Empirically, the study draws on data from the European Social Survey (ESS). The ESS is a cross-national survey conducted every two years since 2002. It is representative of the population aged 15 and over. The survey involves a strict random probability sampling procedure and a minimum target response rate of 70 percent. It is carried out via face-to-face interviews in more than 30 countries. More information about the survey and the topics it covers can be found on its website.

For this article we used the data from the 10th round of the survey, which was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and carried out in 2021/2022 [

59]. More specifically, the present study used data for 16 European countries for which DESI data were available for 2021: Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, and Slovenia. These countries cover different institutional settings and represent a wide range of DESI values—from the lowest to the highest—as well as diverse geographical regions across Europe. These data are limited to individuals aged 25–64 to represent the group of adults, e.g., [

60].

The dependent variable is a dummy variable that indicated whether adults have participated in non-formal job-related adult learning in the previous 12 months (1) or not (0). It is constructed based on the answers to the following question: ‘During the last twelve months, have you taken any course or attended any lecture or conference to improve your knowledge or skills for work?’. We take this question as a measure of participation in adult education and more specifically a measure of one particular type of adult education—non-formal job-related adult learning—which is in line with previous studies that have used the same approach, e.g., [

61]). In this context, non-formal education refers to any organized, structured, and purposeful learning activity conducted outside the formal education system. It is designed for various population groups and delivered through specific forms of learning [

62]. Even when such learning results in a certificate, this certification lacks legal recognition [

53]. Given the heterogenous nature of adult learning and its types, it is a limitation of the study that we measure it using a single dummy variable. However, it still captures the key purpose of the activity—job-related, non-formal adult learning, which is highly significant as it represents the primary means through which employers and employees adjust and update their skills to meet evolving labor market conditions and job requirements [

63].

The main independent variables at the individual level are gender and occupational class. For gender, there are two categories: (1) male and (2) female. As for class, we use a five-occupational-class schema derived from Oesch [

42]. More specifically, it includes the following five categories: (1) higher-grade service class, (2) lower-grade service class, (3) small business owners, (4) skilled workers, (5) unskilled workers. We also include the following individual-level variables: the respondent’s highest level of education in five categories, which refer to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) from 2011—(1) ISCED 0–1, (2) ISCED 2, (3) ISCED 3, (4) ISCED 4, (5) ISCED 5–8; parents’ highest level of education (also in five categories); main activity in the last seven days in three categories—(1) paid work, (2) unemployed, (3) inactive; household total income in three categories—(1) 1st–4th decile group, (2) 5th–9th decile group, (3) 10th decile group; age in three categories—(1) 24–44, (2) 45–54, (3) 55–64; domicile in two categories—(1) village, (2) city, town, or suburbs; and frequency of internet use, whether for work or personal use, in three categories—(1) never or only occasionally, (2) a few times a week or most days, (3) every day.

The main independent variable at the macro level (country level) is the DESI (source: Digital Economy and Society Index (until 2022)—Digital Decade DESI visualization tool). The DESI overall index is calculated as the weighted average of the four main DESI dimensions (access—connectivity; digital public services; skills—human capital; and derived benefits—integration of digital technology) with weights selected by the user. It ranges between 0 and 100. We use the 2021 DESI values for the analysis. Among the 16 countries in the present study the value of this index is lowest in Greece (32.5) and Bulgaria (32.7), and highest in Finland (63.2) and the Netherlands (62.4).

We also include the Gini coefficient of equivalized disposable income (as of 2021) (source: Eurostat EU-SILC survey. Data code: ilc_di12, extracted on 23 May 2024) as a variable at the country level. It is an indicator of income and living conditions in a given country. It also ranges between 0 and 100. The higher the value of the index, the higher in the level of income inequality within a country. The missing values in the individual-level variables were removed in order to allow us to work with the same number of cases across different models and thus to compare the model estimates. The majority of the missing data was in the net household income variable, but we considered it as an important individual-level variable in the analysis. In order to check whether these cases were missing completely at random, we applied two approaches [

64,

65], both of which confirmed that this was the case. First, we created a missing-data dummy variable and conducted

t-tests comparing the cases with and those without missing data to examine whether they differed by age or gender, for which we had data for all respondents in the data set. For gender, as a categorical variable, a Chi-square test was used instead. Both tests indicated that there were no statistically significant age or gender differences between the two groups. Second, we ran a logistic regression model in which the missing-data dummy variable was treated as the dependent variable and gender and age as independent variables. This model also confirmed that the outcome variable could not be predicted by any of these factors, indicating that the cases were missing completely at random. The analyses were conducted on an analytical sample of 13,056 individuals, nested in 16 groups, which is a sufficiently large sample. However, in future work, we might also consider imputation techniques to handle missing data and thus avoid using a listwise deletion approach. The descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1.

We have used multilevel modeling for the data analysis [

66]. More specifically, we estimated a series of logit models with random effects. These models were considered appropriate because our dependent variable was a binary one and because the individuals (Level 1) in the European Social Survey were nested in countries (Level 2). Multilevel models are considered more appropriate than ordinary regression models when the intraclass correlation (ICC) of the null model is higher than 0.05 [

67]. This requirement is met in our study, as the ICC of the null model is 0.162, indicating that 16.2% of the variation in participation in non-formal job-related adult learning in the previous 12 months is due to differences between the countries in which the adults live. Clustered data imply that the observations are dependent, but multilevel models account for this nested structure by including random intercepts at higher levels [

66]. In contrast to fixed-effects models, random-effects models allow the inclusion of variables at Level 2 in the analyses, such as the indexes presented above (DESI and the Gini coefficient), provided that the sufficient number of clusters is between 10 and 20 (in our case, 16) [

66]. Finally, multilevel modelling techniques were chosen because they enable the estimation of cross-level interaction effects, which is particularly important for examining how digital performance, class, and gender interact in shaping participation in adult education. Following the approach of Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal (2012), the results were interpreted using odds ratios that are conditional on the random intercepts specified in the models [

66]. These models were estimated using the xtlogit command in Stata 14.

4. Results

The results of four random-effects logit models estimating whether adults have participated in non-formal job-related adult learning in the previous 12 months are presented in

Table 2. In the first model, only individual-level variables were included. In Model 2, the country-level variables were included. In Models 3 and 4, cross-level interaction terms were included between DESI and gender and between DESI and occupational class, respectively.

The estimates in Model 1 indicate that the lower the occupational class level, the less likely adults are to have participated in non-formal job-related adult learning in the 12-month period preceding the survey, given the other covariates. More specifically, compared to the higher-grade service class, adults in lower occupational classes are much less likely to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning. For example, unskilled workers have an odds of participation that is only 63.2% that of the higher-grade service class. This highlights class-based inequalities in adult learning. This result is consistent across all models, except for Model 4, where an interaction term with occupational class is added, and where the odds ratio for the lower-grade service class also reaches significance.

The analysis further indicates that women are significantly more likely to engage in non-formal job-related adult learning. Specifically, the odds of participation among women are approximately 22% higher than among men. This effect is consistent across all models, with the exception of Model 3, which incorporates an interaction term with gender.

As for the interpretation of the results for the other independent variables at the individual level, the lower the respondents’ level of education or that of their parents and the lower their household income, the less likely they are to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning. The analysis also shows that the higher the age, the lower the likelihood of participating in this form of adult learning. Those adults who are unemployed or inactive are less likely to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning. The frequency of internet use is positively associated with participation in non-formal job-related adult learning in the previous 12 months. This suggests that the more often adults use the internet either for work or for personal reasons, the more likely they are to participate in this form of adult learning.

The country-level analysis shows that the higher the digital performance in a given country, the more likely adults living there are to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning (see Model 2 in

Table 2). We did not find a statistically significant association between the Gini coefficient in a given country and adults’ likelihood to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning, which shows that the level of income inequality in a given country is not linked to the likelihood of adults participating in this form of adult learning. Still, it seems that income inequalities matter at least at the individual level, as mentioned above; our analyses show that the higher the net household income reported by an adult, the more likely they are to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning.

It is noteworthy that after adding the country-level variables at Level 2, the ICC decreased from 0.162 to below 0.05 (specifically, to 0.038) which shows that most of the country-level differences in the outcome variable (participation in non-formal job-related adult learning in the previous 12 months) have been explained.

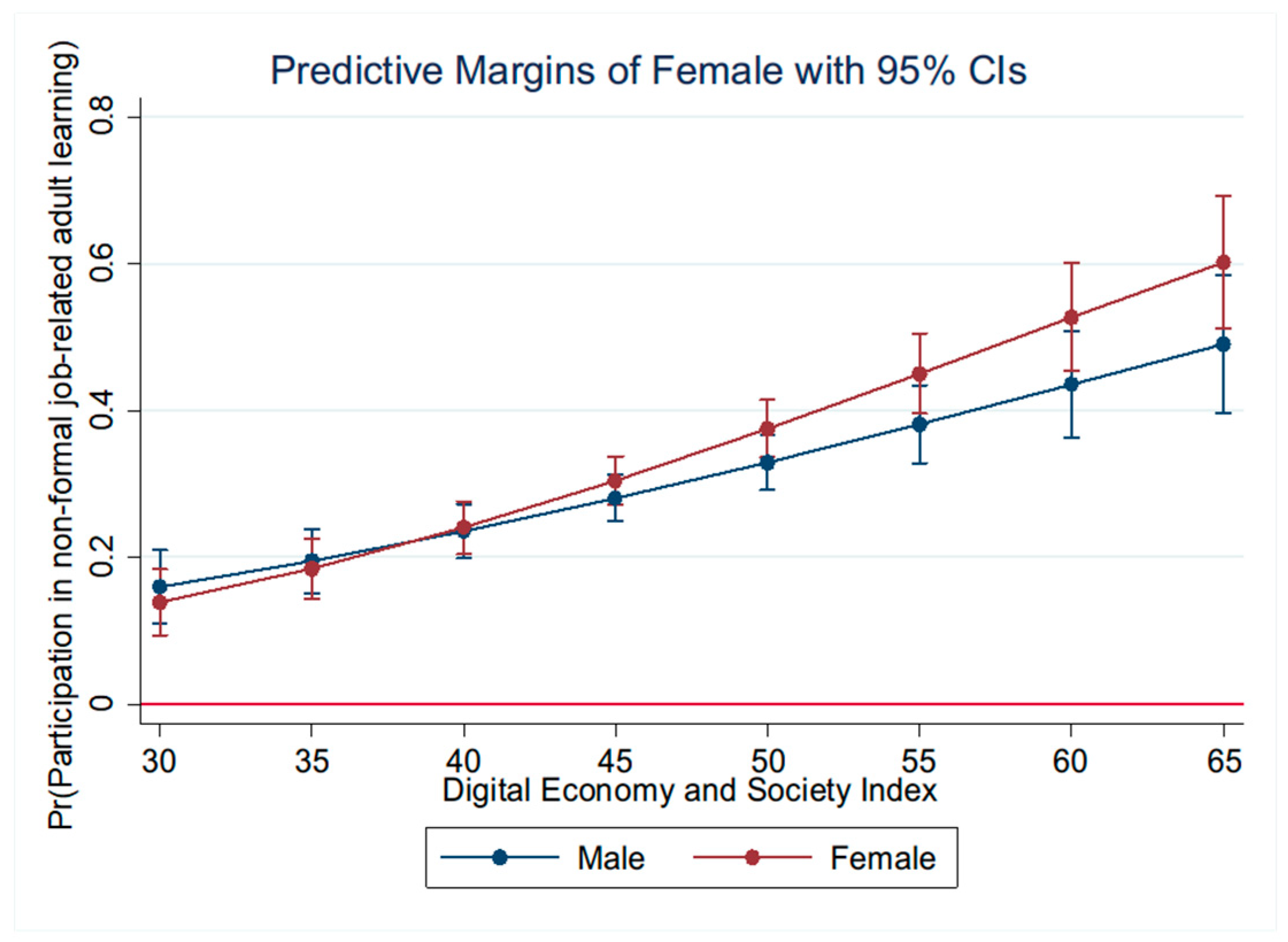

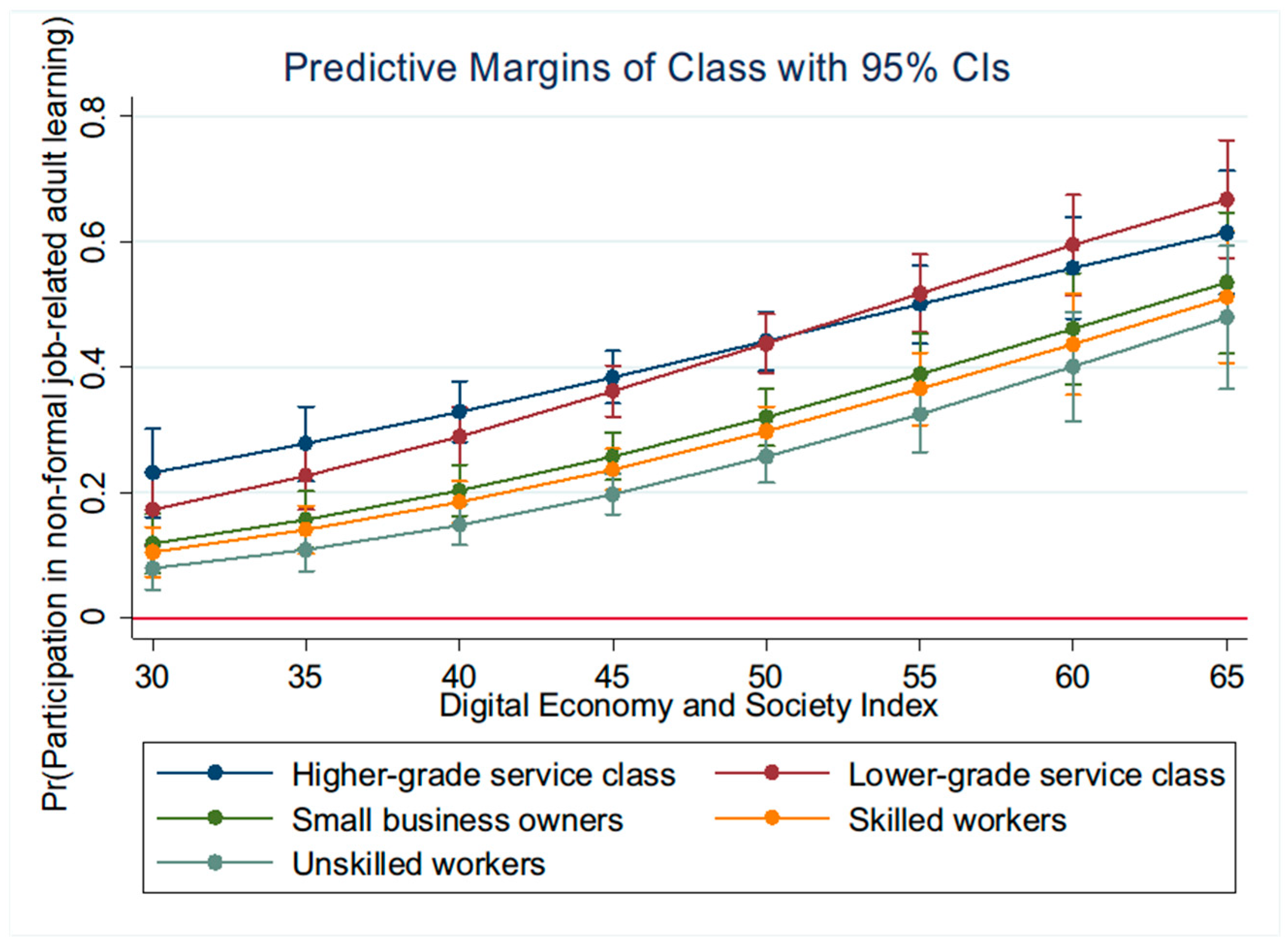

Models 3 and 4 show that there are cross-level interaction effects between DESI and gender and between DESI and occupational class, respectively. To facilitate the interpretation of the cross-level interaction effects presented in Models 3 and 4, we illustrate them graphically in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. The positive interaction term DESI x female means that women in countries with a higher level of digital performance are more likely to participate in non-formal job-related adult learning than men. More specifically, each one-point increase in DESI is associated with 2.2% higher odds of women, compared to men, participating in this form of adult learning. This suggests that women participate in non-formal job-related adult learning more than men, and digitalization amplifies this advantage slightly, reflecting gendered benefits of digital transformation.

In the case of class, we found evidence of a positive interaction between DESI and the lower-grade service class, skilled workers, and unskilled workers. This indicates that the differences in the likelihood of adults participating in non-formal job-related adult learning between the classes are smaller in countries with higher levels of digital performance.

Overall, these results clearly show that occupational class is the strongest predictor of participation in non-formal job-related adult learning. Furthermore, each one-point increase in DESI is associated with a 5.7% higher odds of participation, with particularly strong positive effects for lower occupational classes, partially mitigating inequalities.

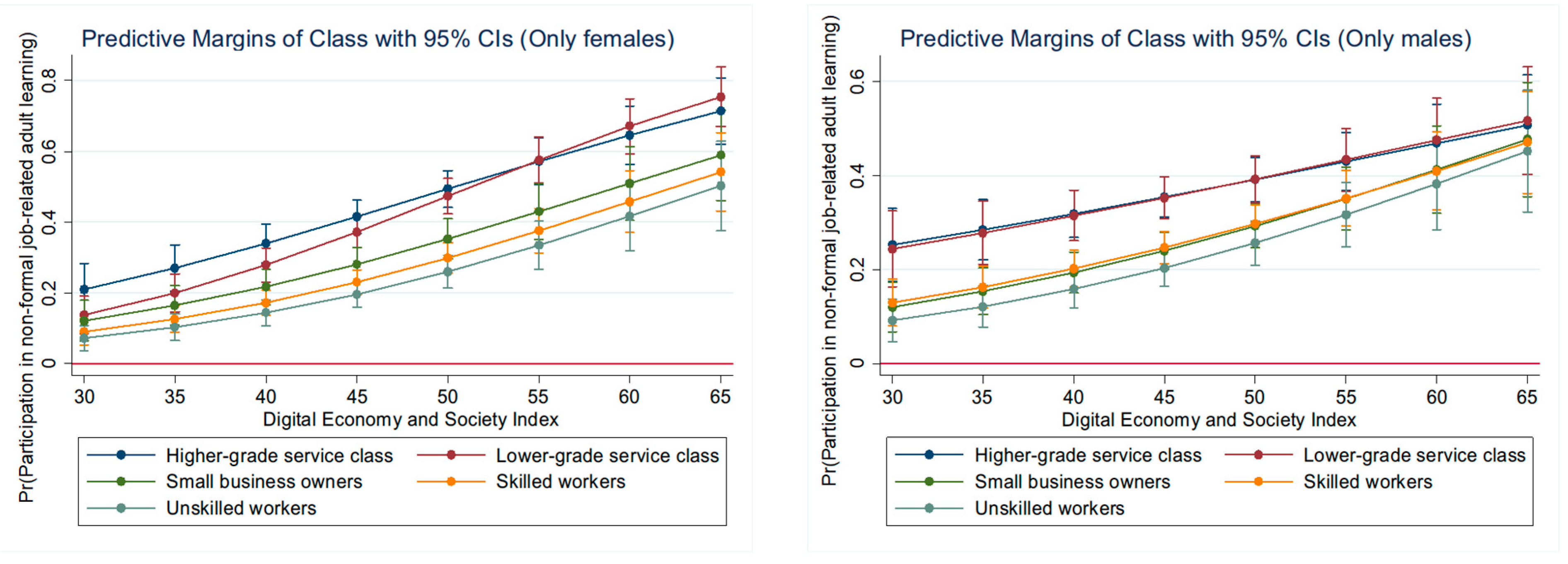

The analysis also provides evidence of gender differences in the relationship between occupational classes and participation in non-formal job-related adult learning across countries with different levels of digital performance. Thus, we found a positive interaction between DESI and the lower-grade service class for women, whereas for men we found positive interaction terms between DESI and small business owners, skilled workers, and unskilled workers (see

Figure 4).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper contributes to understanding the impact of digitalization on participation in adult education (specifically, non-formal job-related adult learning) at the national and individual levels. The theoretical framework of this research is based on, and aims to contribute to, the literature on digital inequalities investigating the dynamic between the digital divide and social inequalities and finding arguments for the reproduction and/or transformation dilemma. Adult education is investigated from the perspective of the importance of gender for the take-up of the opportunities for non-formal job-related adult learning. Intersectional research is included in this paper, studying the implications of inter-categorial and intra-categorical differences in the chances of participation in adult education for women compared to men in developed EU countries. At a policy level, we use the concept of the three functions of social investment to target specific groups in the process of digital transformation.

Concerning the first research question, our results show that the individual characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of participating in non-formal job-related adult learning are frequency of internet use, higher occupational class, and being female. These findings support the premise that a higher frequency of internet usage increases the possibility for non-formal job-related adult learning. The positive effects of digitalization can be observed for all social classes and for men and women, although unevenly. Higher-grade service class people have a higher likelihood of participating in adult education. This finding supports the reproduction thesis that higher-status groups benefit more from digitalization.

An interesting finding is that women in the EU context participate more in adult education compared to men. Occupational gender segregation is a social mechanism explaining this finding. The intersectionality of gender and occupational class is related to the existence of horizontal gender segregation within occupational classes. Women from the lower service class participate more in adult education compared to men, who are predominantly part of the working class. The gender-specific labor processes and occupation of jobs require the use of digital technologies to different degrees for the service and working classes.

Our results indicate, concerning the second research question about the association of digital performance at the country level, that a higher DESI, which reflects a broader scope of digital transformation, is beneficial for all occupational classes except the lower-grade service class (Model 2). There is a slight decrease in gender inequalities; however, the positive effect for women remains. This result is in line with the popular belief that when the tide is high all boats float. Nevertheless, occupational inequalities persist.

The

second research question also includes the impact of income inequality at the country level on participation in adult education. We observed that the overall income inequality at the country level (Gini coefficient) does not have a statistically significant association with participation in non-formal job-related adult learning. However, at the individual level of poverty for low-income groups (1st–4th decile), lower occupational class (unskilled workers) has a significant negative effect. In previous research [

17], special attention has been given to South European countries which are OECD members—Italy, Spain, and Portugal—where both unemployment and inequality are at higher levels. Italy is also among the three EU countries at the bottom for digital performance (DESI). Portugal is in the middle of the DESI scale. In addition, our sample includes Bulgaria—a South-Eastern European country with a post-communist transitional context. Bulgaria is among the countries experiencing decreasing incomes in the middle of the income structure and has the highest Gini coefficient among the EU countries. The low positions in the DESI index cannot prevent the reproduction of the negative effects for unskilled workers and for the unemployed on chances for adult education participation. Future research has to widen the geographical scope within Europe, including more South-Eastern European countries but also widening the global perspective to countries beyond those included in the OECD, such as the USA, Australia, and Japan. Further research on digital inequalities related to occupational groups should also include more policy-related indicators like governmental spending on education, unemployment, and social protection in the empirical analysis.

Concerning the

third research question, we identified cross-level interaction effects between DESI and gender and between DESI and class regarding participating in non-formal job-related adult learning, respectively. Our contribution lies in the findings highlighting the positive effects of digitalization performance on the lower-grade service class and on skilled and unskilled workers. The results of this paper go beyond the thesis that life chances improve for all social classes when the equality of conditions is higher [

42]. Our study points to the consequences of gender segregation in the labor market on the ability of men and women to benefit from digital transformation within their occupational class. Occupational structure helps to explain why women benefit more from digitalization and from higher DESI levels. In countries with a high DESI, investments in public sector digitalization are greater. In public sectors such as education, healthcare, and e-government, women represent a higher share of the workforce than men. Up-skilling of women in lower service class positions can improve their social mobility chances through additional training and help them to attain better-paid positions. In contrast, men’s occupations tend to be more technical or manual in nature. For less-qualified manual workers, the main risk of job loss is posed more by automation than by digitalization. Men in higher managerial positions already possess digital skills and therefore gain less from further improvements compared to women.

Focusing on the intersection between occupational class and gender is important because occupations correlate with various financial and non-financial differences. Previous research points to working conditions, wages, promotions, and career chances in male and female occupations which are not comparable [

51]. The present research fills the gap in understanding occupational gender segregation by studying the impact of digitalization at the macro level and the chances for additional training for men and women working in different occupations with uneven digital requirements. This study extends the research from mainly income inequalities to those concerning skills development through adult education.

The differentiation defined in intersectional research between inter-categorial and intra-categorical investigation has been applied. We not only demonstrated better chances to participate in adult education for women compared to men in developed EU countries, but we also obtained results for the differences within both categories—of men and of women. At this second stage of the analysis, the notable result is that a higher digital performance at the country level enhances the educational chances of workers—both less and more qualified—and of small business owners. This result can inform motivation campaigns targeting workers to take part in additional learning.

The contribution of our results is that they reveal the importance of digital performance in mitigating the digital gap between the occupational classes, reinforcing the understanding that it is essential to minimize this gap [

33]. Participation in work-related courses provides an opportunity to increase an individual’s wellbeing and to reduce the risks of losing jobs, which can occur with the process of intensive digital transformation and the requirements of up-skilling of the workforce. We, however, also highlight the reproduction effects of digitalization because of the remaining multigenerational disadvantage in adult education participation for low-education individuals.

This study suggests that the digital performance in a country contributed to reducing gender and class inequalities in participation in adult education, which has important policy implications. Although the share of digital inactivity is relatively low; participation in online courses is not yet widespread among the benefits derived from internet use. Social investment policies are important for the maintenance of “the stock of human capital”, for facilitating life course transitions, for “work–life balance flows”, and to ensure income protection through “inclusion buffers” [

58]. The development of digital access and skills among people in different life course stages becomes crucial for their life chances and addressing the reproduction of social inequalities within the digital divide. Special focus is needed for workers in their late careers, given empirical findings that higher age limits individuals’ ability to take advantage of digitalization. Social investments in the skill development of employees in their later careers may potentially increase not only their employability but also help them to adapt to the changing economic and digital societal context. At the same time, retraining and upgrading the skills of older employees contributes to macroeconomic performance. In this way, social investments provide the conditions for “inclusive growth” [

68].

The social investment function of facilitating “work–life balance flows” also addresses everyday care responsibilities, highlighting the need for more free time and flexible learning opportunities, particularly for women, to access online courses at any time and place. Income protection is similarly crucial, as low-income groups often lack the resources to access and use digital devices. Reducing income inequality through effective social protection is equally important from the social investment perspective, alongside maintaining low unemployment rates. Our results support the thesis that the three functions of social investment should be applied in a complex, mutually complementary manner.

Social investment policies are directed toward increasing individuals’ capabilities and resilience to overcome economic and societal risks in the context of global economic uncertainty. The economic resilience of the middle class is identified as one of the global indicators reflecting overall societal stability [

69]. Social investment policies that support small businesses and entrepreneurs, in addition to offering training and skills development, aim to promote “innovation-friendly environments” [

70]. Women’s entrepreneurship in the digital economy remains an underdeveloped target. Training can support women in deciding to establish start-ups, helping them to overcome initial financial insecurity and low levels of willingness to take financial risks. The establishment of digital hubs at the regional level, funded by public programs, helps small businesses to overcome security challenges associated with the digital economy.

It is important to emphasize that the analyses provide evidence of associations between variables; however, they do not imply causality. Further research is needed to investigate causal relationships between occupational gender segregation, the motivation of boys and girls to study STEM disciplines, and participation in ICT occupations. Preventing polarization in society between the digitally active and those excluded from the technological transformation remains a major challenge for the labor market and the welfare system. In this way, the present paper contributes to the literature on the need for social support for digital inclusion, based on quantitative data that reveal the importance of socio-economic (occupational class) and socio-cultural (gender) factors in participation in non-formal job-related adult learning. The need for social support is particularly significant for women and men in occupations within the working class, lower service class, and small business owners, where there is less work-related demand and fewer internet skills. This insight connects this paper with the literature dedicated to “support networks”, which investigates the “strength of the relationships between individuals” [

71]. Further research should focus more on the need for support, as well as the motivation and readiness of late-career employees to receive additional digital training. It may also be interesting to explore whether the level of digital performance in a given country moderates the relationship between gender, occupational class, and participation in online courses.

Ongoing research on digitalization and adult education faces new challenges posed by the rapid development of AI. In the field of AI, gender segregation is observed in skills, roles, and sectors [

72]. A limitation of the paper is its focus on digitalization in terms of internet use, as it does not address the emerging challenges related to the integration of AI in adult education and its implications for occupational gender segregation. This remains a task for future research, together with the aim of wider geographical outreach.