Assessment of TCFD Voluntary Disclosure Compliance in the Spanish Energy Sector: A Text Mining Approach to Climate Change Financial Disclosures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Text Mining in the TCFD Framework: Approaches and Gaps

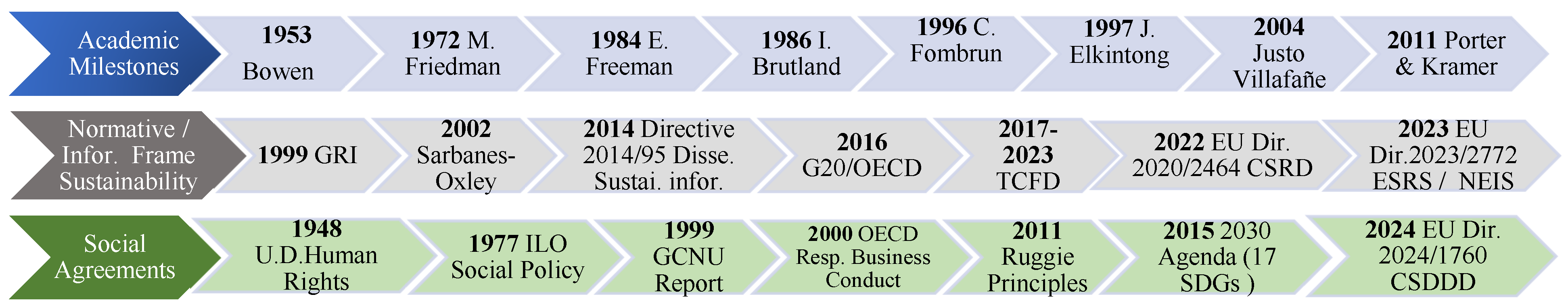

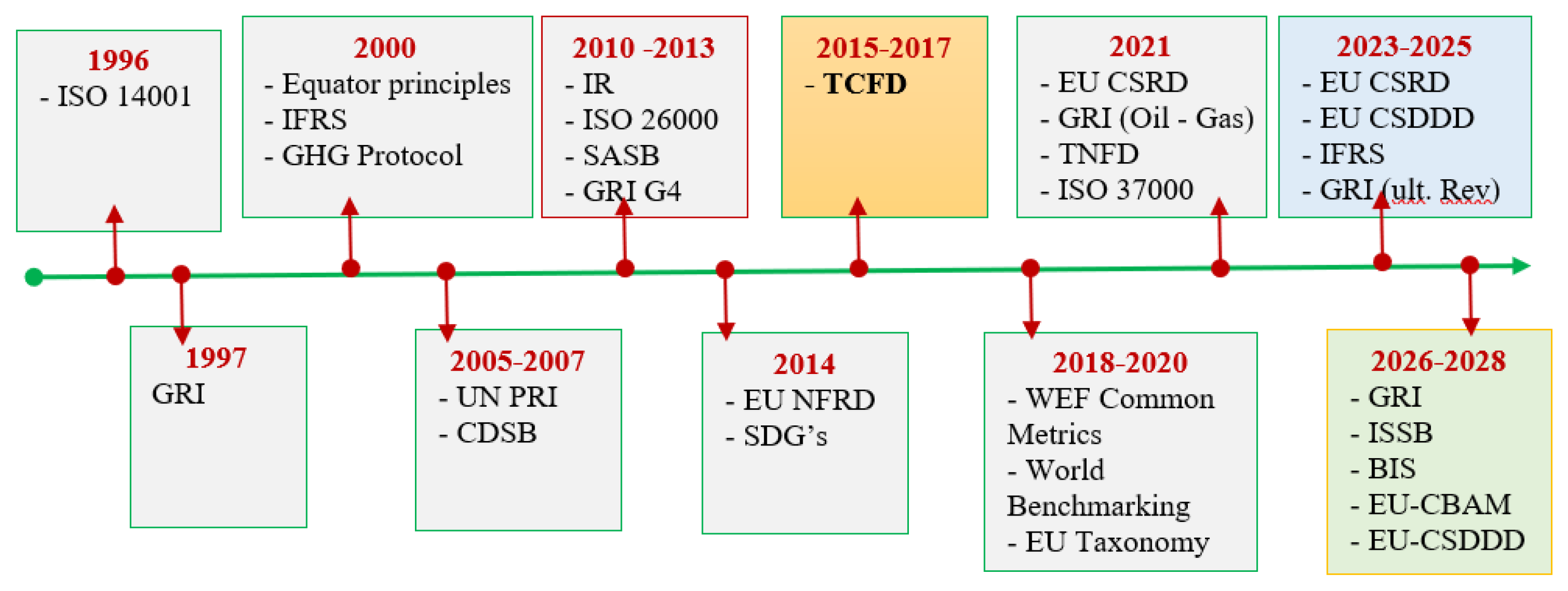

2.2. ESG Regulatory Frameworks: Historical Developments and Global Trends

2.3. The TCFD Framework, a Global Standard for Enterprise Reporting

2.4. Text Mining in Financial Reporting Analysis, Evolution, and the Future of NPL

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Text Mining Process

3.1.1. Definitions and Objectives

3.1.2. Tools and Resources Used

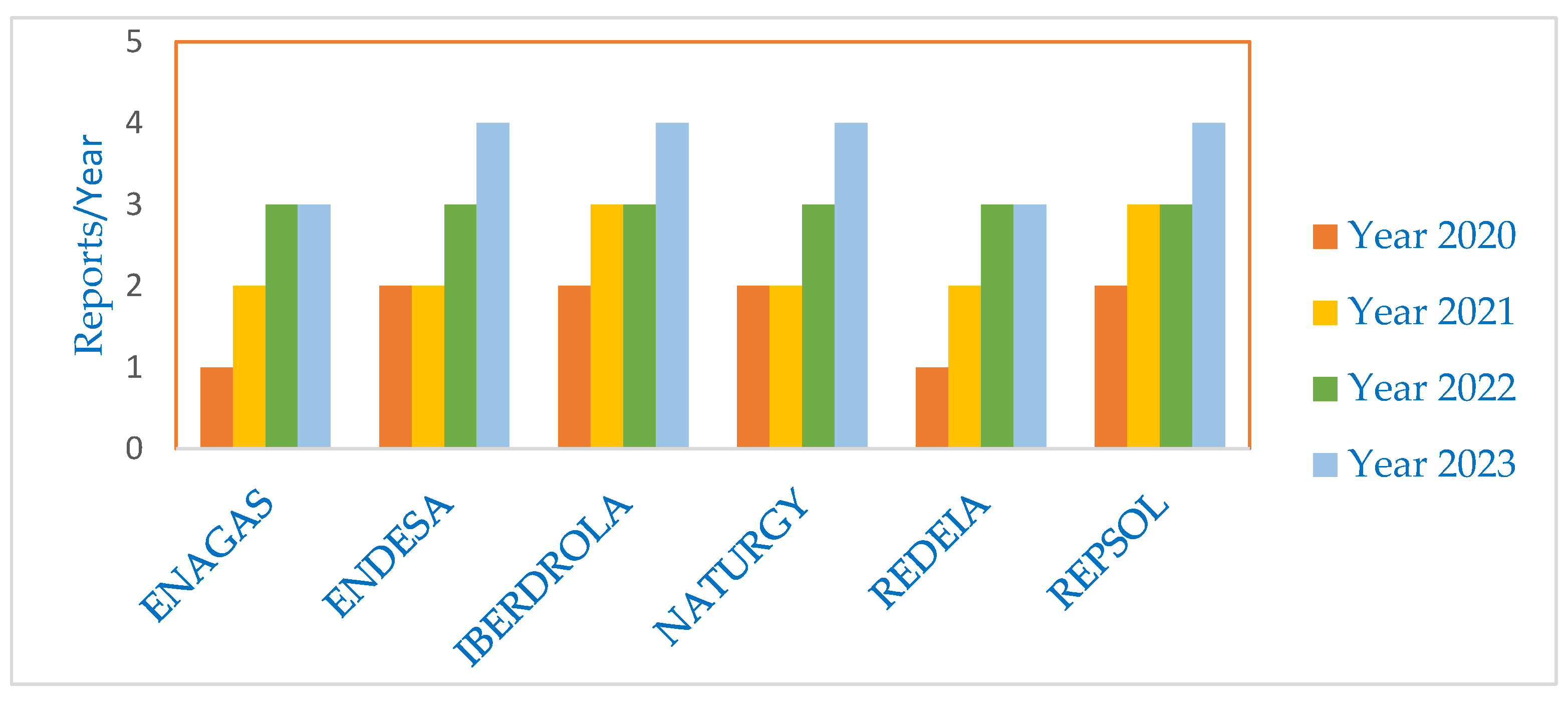

3.1.3. Document Collection and DATA PREPARATION

3.1.4. Text Preparation

3.1.5. Structured Text Representation and Extraction

3.1.6. Analysis and Information Extraction

3.1.7. Visualization of Results with Tokenization and Indexing

3.1.8. Revision and Validation in Taxonomy Creation

3.1.9. Evaluation of Results (Model Accuracy)

3.1.10. Implementation and Utilization

3.2. Assessment Based on ESG Reporting Aspects Under the TCFD Standard

3.3. Development of an Index Based on Compliance with the TCFD in ESG Reports

4. Results

4.1. Results of Text Mining Applied to TCFD Compliance Analysis

4.2. Results of the Aspect-by-Aspect Assessment of Financial and ESG Reporting

4.3. Results of Comparative Analysis of TCFD Compliance Using a Quantitative Index

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CSDDD | Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| ESRS | European Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| FTS | full-text searches |

| FSB | Financial Stability Board |

| G20 | Group of Twenty |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas emission management |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| IBEX-35 | Spanish Stock Market Index |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board |

| IFRS S1 | International Financial Reporting Standards. (Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information) |

| IFRS S2 | International Financial Reporting Standards. (Climate-related Disclosures) |

| IMRaD(I) | Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion (Implications) |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| NFRD | Non-Financial Reporting Directive |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TCFD | Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures |

| Portable Document Format | |

| RDs | Recommended Disclosures |

| SCs | Specific Concepts |

| SFDR | Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation |

References

- David, B.; Giordano-Spring, S. Climate reporting related to the TCFD framework: An exploration of the air transport sector. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2021, 42, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingler, J.A.; Kraus, M.; Leippold, M.; Webersinke, N. ClimateBert: A pretrained language model for climate-related text. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2110.12010. [Google Scholar]

- Maji, S.G.; Kalita, N. Climate change financial disclosure and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Indian energy sector based on TCFD recommendations. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2022, 17, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCFD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures). Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures; FSB: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Villafañe, J. Reputación Corporativa; Pearson Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Quiñones, M.; Aliende, I.; Escot, L. Application of data science for building corporate reputation strategy: An analysis in business intangibles scoping review. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2025, 6, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif-Alyousfi, A.Y.; Alshammari, T.R. Environmental Sustainability and Climate Change: An Emerging Concern in Banking Sectors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). Working Group on Climate Finance Disclosures: Progress Report in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023; FSB: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/about/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Nisanci, D.A. Financial Stability Board (FSB), on climate-related financial disclosures. In World Scientific Encyclopedia of Climate Change; World Scientific: Singapore, 2021; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Hossain, A. An exploratory study on climate-related financial disclosures: International evidence. In Corporate Narrative Reporting: Beyond the Numbers; Marzouk, M., Hussainey, K., Eds.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon—Climate Change and Financial Stability. Speech Presented at Lloyd’s of London, London, UK, 29 September 2015. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2015/breaking-the-tragedy-of-the-horizon-climate-change-and-financial-stability (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Tyagi, S. What comes next: Responding to recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD). APPEA J. 2018, 58, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P.F.A.; Harris, P.; Caykoylu, S. The Impact of Corporate Characteristics on Climate Governance Disclosure. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Robisco, A.; Carbó, J.M. Analysis of CBDC narrative by central banks using large language models. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58 Pt C, 104643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Krzus, M.P. Implementing the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures Recommendations: An Assessment of Corporate Readiness. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2019, 71, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Kim, J.D.; Bae, S.M. Determinants of Global Banks’ Climate Information Disclosure with the Moderating Effect of Shareholder Litigation Risk. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Kumar, R.; Joshi, A. Technologies Empowered Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG): An Industry 4.0 Landscape. Sustainability 2022, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu Pinillos, A.; Castilla Vida, A.; García Tejerina, I. Sostenibilidad: El Tsunami Regulatorio; EY España: Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://www.ey.com/es_es/insights/rethinking-sustainability/sostenibilidad-tsunami-regulatorio (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Zhang, A.Y.; Zhang, J.H. Renovation in environmental, social and governance (ESG) research: The ap-plication of machine learning. Asian Rev. Account. 2024, 32, 554–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Business Roundtable. Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote an Economy that Serves All Americans; Business Roundtable: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups. Off. J. Eur. Union Law 2014, 330, 1–9. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/95/oj (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Godawska, J. The use of corporate external environmental reporting in the evaluation of the state environmental policy. Econ. Environ. 2023, 86, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on corporate sustainability reporting (CSRD). Off. J. Eur. Union Law 2022, 322, 15–45. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 Supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Sustainability Reporting Standards; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/2772/oj (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Odobaša, R.; Marošević, K. Expected contributions of the European corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD) to the sustainable development of the European Union. EU Comp. Law Issues Challenges Ser. (ECLIC) 2023, 7, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazi, T. The introduction of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting in the EU and the question of enforcement. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2024, 25, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuncu, B. The effects of climate change on accounting and reporting. In New Approaches to CSR, Sustainability, and Accountability; Çalıyurt, K.T., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; Volume 5, pp. 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores. CNMV I. Código de Buen Gobierno de Las Sociedades Cotizadas; Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.cnmv.es/DocPortal/Publicaciones/CodigoGov/CBG_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Bloomberg. Sustainability Data. Bloomberg Terminal. 2025. Available online: https://bba.bloomberg.net (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- MSCI. MSCI ESG Leaders; MSCI Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.msci.com/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Čufar, M.; Belak, J. Beyond Financials: Understanding the Implications of NFRD and CSRD on Non-Financial Reporting. EU Comp. Law. Issues Challenges Ser. (ECLIC) 2024, 47, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.; Gonzalez, J.; Le, Q.; Liang, C.; Munguia, L.-M.; Rothchild, D.; So, D.; Texier, M.; Dean, J. Carbon emissions and large neural network training. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.10350. [Google Scholar]

- Saif-Alyousfi, A.Y.H. Energy shocks and stock market returns under COVID-19: New insights from the United States. Energy 2025, 316, 134546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad Ibrahim, A.E.; Hussainey, K.; Nawaz, T.; Ntim, C.; Elamer, A. A systematic literature review on risk disclosure research: State-of-the-art and future research agenda. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 82, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.F.; James, R.; King, A.; Lee, E.; Soderstrom, N. Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) implementation: An overview and insights from the Australian Accounting Standards Board dialogue series. Aust. Account. Rev. 2022, 32, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulluscio, C.; Puntillo, P.; Luciani, V.; Huisingh, D. Climate change accounting and reporting: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leaniz, P.M.G.; del Bosque Rodríguez, I.R. Corporate image and reputation as drivers of customer loyalty. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2016, 19, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G. Sustainability disclosure and reputation: A comparative study. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2011, 14, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y. FinBERT: A large language model for extracting information from financial text. Contemp. Account. Res. 2022, 40, 806–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırçova, I.; Esen, E. The effect of corporate reputation on consumer behaviour and purchase intentions. Manag. Res. Pract. 2018, 10, 21–32. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10201/111654 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Tőzsér, D.; Lakner, Z.; Sudibyo, N.A.; Boros, A. Disclosure Compliance with Different ESG Reporting Guidelines: The Sustainability Ranking of Selected European and Hungarian Banks in the Socio-Economic Crisis Period. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Climate risk disclosure and financial analysts’ forecasts. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, W.; Wu, S.J.; Raghupathi, V. Understanding Corporate Sustainability Disclosures from the Securities Exchange Commission Filings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei, Z.; Linnenluecke, M.; Bui, B. The disclosure of climate-related risks and opportunities in financial statements: The UK’s FTSE 100. Meditari Account. Res. 2023, 32, 1031–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, J. Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M.; Feuerriegel, S. Decision support from financial disclosures with deep neural networks and transfer learning. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 104, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Rauber, R. Diverse climate actors show limited coordination in a large-scale text analysis of strategy documents. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-de Castro, G.; Amores-Salvadó, J.; Navas-López, J.E.; Balarezo-Núñez, R.M. Reputación ambiental corporativa: Explorando su panorama definitorio. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 29, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Automated text analyses of sustainability & integrated reporting: A literature review of empiri-cal-quantitative research. J. Glob. Responsib. 2023, 14, 530–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.-I.; Caminero, T. Application of text mining to the analysis of climate-related disclosures. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Swierszcz, A.; Shah, J.M.; Bohr, K.; Partridge, K.; Choi, T.J. Advancing Sustainability Reporting in Canada: 2019 Report on Progress. Account. Perspect. 2020, 19, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NISO. Guidelines for Abstracts (Z39.14-1997 (R2015); National Information Standards Organization: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.niso.org/publications/ansiniso-z3914-1997-r2015-guidelines-abstracts (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Reese, S.D. Writing the conceptual article: A practical guide. Digit. J. 2022, 11, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luccioni, A.; Baylor, E.; Duchene, N. Analysing sustainability reports using natural language processing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.08073. [Google Scholar]

- Putatunda, J. Building AI Agents for Financial Report Analysis: Enhancing ESG Disclosures. Fitch Learning Webinar. 2024. Available online: https://www.fitchlearning.com/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Alzeghoul, A.; Alsharari, N.M. Impact of AI Disclosure on the Financial Reporting and Performance as Evidence from US Banks. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equator Principles Association. Equator Principles; Equator Principles Association: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.equator-principles.com (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI Standards; Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/standards-development/sector-standard-for-oil-and-gas/ (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- United Nations Global Compact. United Nations Global Compact; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- World Resources Institute; World Business Council for Sustainable Development. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard; World Resources Institute & World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 26000; Social Responsibility. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Farzaneh Amani, A.; Fadlalla, A.M. Data mining applications in accounting: A review of the literature and organizing framework. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2017, 24, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment (EU Taxonomy). Off. J. Eur. Union Law 2020, 198, 13–43. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/852/oj (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector (SFDR). Off. J. Eur. Union Law 2019, 317, 1–16. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/2088/oj (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/1760 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on corporate sustainability due diligence (CSDDDD). Off. J. Eur. Union Law 2024, 1760, 5–27. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1760/oj (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Cui, X.; Li, R.; Xue, S.; Zhang, X. Mandatory versus voluntary: The real effect of ESG disclosures on corpo-rate earnings management. J. Int. Money Financ. 2025, 154, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, K.; Feldb, L. Shifting boundaries: A transnational legal perspective on the EU corporate sustainability due diligence directive. Transnatl. Legal Theory 2024, 15, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friske, W.; Hoelscher, S.A.; Nikolov, A.N. The impact of voluntary sustainability reporting on firm value: Insights from signalling theory. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 51, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. The necessity for developing a mandatory environmental information disclosure system for ESG in China: From the perspective of corporate compliance. Front. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 17, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.E.; Figueiredo, M.D. Practicing Sustainability for Responsible Business in Supply Chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores-Salvadó, J.; Cruz-González, J.; Delgado-Verde, M.; González-Masip, J. Green technological distance and environmental strategies: The moderating role of green structural capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2021, 22, 938–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R. Briefing: Task force for climate financial disclosures (TCFD) for the property and construction industry. Sustain. Build. 2020, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, D. Disclosures of banks’ sustainability reports, climate change, and central banks: An empirical analysis with unstructured data. Risk Gov. Control Financ. Mark. Inst. 2024, 14, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Y. Neural Network Methods for Natural Language Processing; Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 10, pp. 1–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganathan, T.; Senthilkumar, S.; Balakrishnan, V. Machine learning and data analytics for environmental science: A review, prospects and challenges. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 955, 012107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT 4; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://openai.com/gpt-4 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Miranda, A. Environmental Claims, Unfair Competition and Patterns in Comparative Jurisprudence: On Greenwashing. Noteb. Transnatl. Law 2024, 16, 423–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno, R.; González, C.I. The role of a green factor in stock prices: When Fama and French go green. J. Credit. Risk 2023, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, A.T.; Adeoye, O.B.; Addy, W.A.; Okoye, C.C.; Ofodile, O.C.; Ugochukwu, C.E. Promoting sustainability in finance with AI: A review of current practices and future potential. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Toro, J.A.; Ferré-Pavia, C. Los intangibles de la marca y su efecto en la reputación corporativa. Rev. Comun. 2019, 18, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Shrives, P.J. Content analysis in environmental reporting research: Enrichment and testing of the method in a British-German context. Br. Account. Rev. 2010, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M.; Huse, M. Influence of corporate governance, industry, and country factors on environmental reporting. Scand. J. Manag. 1997, 13, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter “greenwashing”: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, L.; Unerman, J.; De Villiers, C. Evaluating the integrated reporting journey: Insights, gaps, and agendas for future research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 1294–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borré, S.S.; Gelmini, L. Global corporate performance evaluation and sustainability reporting. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2024, 21, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S. A thematic analysis of English and American literature works based on text mining and sentiment analysis. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, K.; Ghandour, R.; Histon, W. Greenwashing and brand perception: A consumer sentiment analysis on organisations accused of greenwashing. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2024, 21, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Author(s) | Title | Method/Approach | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | [58] Luccioni, A., Baylor, E., & Duchene, N. | QlimateQA: Analyzing Sustainability Reports Using Natural Language Processing | Development of a specific NLP model/identifying climatic passages in financial texts | Development of QlimateQA, a domain-specific model to identify climate-relevant passages in financial reports, enhancing the accuracy of analyses. |

| 2022 | [2] Bingler, J., Kraus, M., Leippold, M., & Webersinke, N. | ClimateBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Climate-Related Text | Pre-trained BERT model/extraction of technical information from climate texts | Development of ClimateBERT, a pre-trained language model specifically for climate texts that facilitates the identification of relevant sections in the TCFD reports and improves the extraction of technical information. |

| 2022 | [43] Huang, A.H., Wang, H., & Yang, Y. | FinBERT: A Large Language Model for Extracting Information from Financial Text | Adapted BERT model/sentiment classification and analysis of ESG financial texts | Presentation of FinBERT, an adaptation of the BERT model to the financial field, used for the classification and analysis of sentiment in financial texts related to ESG disclosures, showing advantages over traditional techniques. |

| 2023 | [53] Velte, P. | Automated text analyses of sustainability & integrated reporting: A literature review of empirical-quantitative research | Systematic review/methodological assessment in text mining and NLP for sustainability reporting | The study presents a systematic review of the literature on the application of text mining and NLP techniques in the analysis of sustainability and integrated reports. It examines the methods used and the research objectives, highlighting both the progress made and the current limitations. |

| Years | ERA | Techniques Employed | Main Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 – 1980 | First ERA: Rule-based systems | Heuristic methods. Regular expressions for pattern matching WordNet, Gensim, and fastText. | Rapid implementation. Accuracy guaranteed by human intervention. Requires expert knowledge and is time-consuming. |

| 1990 – 2010 | Second ERA: Statistical methods | Machine learning models such as Naïves/Bayes/logical regression/ SV/LDA/HMM. | Less reliance on customized rules. Data-driven approach. Requirement for manual feature selection. |

| 2010 – Today | Third ERA: Machine learning approaches | Deep learning models such as RNN, LSTM, GRU, CNN. Transformers and pre-trained models such as BERT and GPT. Autonomous AI agents. | Automatic feature generation. Better management of unstructured data. Self-learning capability. High-quality and cost-effective results. |

| Enagás | Endesa | Iberdrola | Naturgy | Redeia | Repsol | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of reports: | 9 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 64 |

| Successful Conversion: | ≈94.80% | ≈96.00% | ≈95.23% | ≈95.90% | ≈95.50% | ≈95.45% | ≈95.31% |

| Cause of Failure: | Graphs and information tables do not convert properly. Tables not converted properly. Bullets require manual correction. | ||||||

| Resolution: | Manual—minimizations of human bias/improved post-error resolution. | ||||||

| Enagás | Endesa | Iberdrola | Naturgy | Redeia | Repsol | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of sentences (key and thematic sentences) | 1.264 | 1.897 | 3.152 | 2.837 | 1.645 | 2.465 | 13.260 |

| Number of bullets (elements identified) | 57 | 62 | 71 | 68 | 54 | 86 | 398 |

| No. of objects (prioritized list) | 89 | 97 | 112 | 75 | 106 | 134 | 613 |

| No. of Tables (structured data) | 33 | 42 | 40 | 37 | 35 | 45 | 232 |

| TOTAL (%) | ≈13.7% | ≈13.1% | ≈21.7% | ≈19.6% | ≈11.3% | ≈20.6% | 14.503 (100%) |

| Areas | Recommended Disclosures (RDs) | Specific Concepts (SCs) | Query | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3—Risk Assessment and Management | RD8—Corporate resilience and reputation plan against climate change | Frequency of follow-up in relation to the “reputation” | reputation AND plan AND climate change reputation AND plan AND resilience reputation AND plan AND (strategy OR sustainable) | 3 2 1 |

| 4 Areas | 11 Recommended Disclosures (RDs) | Detailed Disclosures | Total Queries |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1— Government | RD1—Structures and processes for monitoring climate risks RD2—Senior management involvement in climate management | 3 8 | 9 18 |

| A2— Strategies and Opportunities | RD3—Impact of climate change on the organization RD4—Development of green products for diversification, adaptation, and resilience RD5—Identification of climate risks and opportunities | 7 11 2 | 10 12 3 |

| A3— Risk Assessment and Management | RD6—Climate risk assessment and management RD7—Adaptation to changes in regulation RD8—Corporate resilience and reputation plan against climate change | 2 7 3 | 4 12 6 |

| A4— Metrics and Targets | RD9—Measuring and quantifying climate impact in the company RD10—GHG Emissions Protocol and Management, Scope 1, 2, and 3 RD11—Objectives and actions for the use of renewable energies and business sustainability | 4 6 4 | 10 12 7 |

| 4 Areas | 11 Recommended Disclosures (RDs) | 70 Specific Concepts (SCs) |

|---|---|---|

| A1— Government | RD1—Structures and processes for monitoring climate risks RD2—Senior management involvement in climate management | SC1—management, remuneration, periodicity, monitoring SC2—management, remuneration, periodicity, monitoring, sustainability committee |

| A2— Strategies and Opportunities | RD3—Impact of climate change on the organization RD4—Development of green products for diversification, adaptation, and resilience RD5—Identification of climate risks and opportunities | SC3—criteria, strategy, effect, reputational risks, reporting standards, technological utilization, sustainable energy SC4—climate scenarios and temperature increase SC5—tangible risks, climate change risks, shift risks, cost reduction opportunities, financing, mortgages, sustainable financing, short-term, medium, long-term, several weather events |

| A3— Risk Assessment and Management | RD6- Climate risk assessment and management RD7—Adaptation to changes in regulation RD8—Corporate resilience and reputation plan against climate change | SC6—environmental risks, prospects, shift risks, tangible risks, procedures, disclosure guidelines, compliance risk, reputation risk, economic risk, legislative controls, international agreements SC7—risk management strategies, materiality, emission valuation, litigation, severe weather events, renewable energy, transition costs SC8—strategy and crisis response |

| A4— Metrics and Targets | RD9—Measuring and quantifying climate impact in the company RD10—GHG Emissions Protocol and Management, Scope 1, 2, and 3 RD11—Objectives and actions for the use of renewable energies and business sustainability | SC9—reduction, CO2 emissions, refuse, energy use, water use, fuel use, renewable energies SC10—Scope, CO2 emissions, CO2 units, CO2 intensity, CO2 e SC11—target, reduction, CO2 emissions, refuse, energy use, water use, fuel use, renewable energies, renewable energies |

| Assessment Aspects of Climate Disclosure in Businesses | Enagás | Endesa | Iberdrola | Naturgy | Redeia | Repsol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Quality of information | ||||||

| • Accuracy and reliability | Medium | High | High | High | Medium | High |

| • Relevance to stakeholders | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| • Inclusion of quantitative and qualitative data | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| 2. Extension of Disclosure | ||||||

| • TCFD Aspects Coverage (Governance, Strategy, Risks Metrics, and Targets) | Partial | Partial | Complete | Partial | Partial | Complete |

| • Details of actions to address climate challenges | Limited | Limited | Detailed | Limited | Limited | Detailed |

| 3. Relevance and Contextualization | ||||||

| • TClarity of presentation | Unclear | Clear | Clear | Clear | Unclear | Clear |

| • Connection with sustainability strategy | Evident | Explicit | Clear | Explicit | Explicit | Explicit |

| Years: 2020–2021–2022–2023 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | RD1 | SC1—management, remuneration, periodicity, monitoring | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RD2 | SC2—management, remuneration, periodicity, monitoring, sustainability committee | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| A2 | RD3 | SC3—criteria, strategy, effect, reputational risks, reporting standards, technological utilization, sustainable energy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| RD4 | SC4—climate scenarios and temperature increase | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| RD5 | SC5—tangible risks, climate change risks, shift risks, cost reduction opportunities, financing, mortgages, sustainable financing, short-term, medium, long-term, several weather events | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| A3 | RD6 | SC6—environmental risks, prospects, shift risks, tangible risks, procedures, disclosure guidelines, compliance risks, reputation risk, economic risk, legislative controls, international agreements | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| RD7 | SC7—risk management strategies, materiality, emission valuation, litigation, severe weather events, renewable energy, transition costs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| RD8 | SC8—strategy and crisis response | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| A4 | RD9 | SC9—reduction, CO2 emissions, refuse, energy use, water use, fuel use, renewable energies, | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| RD10 | SC10—Scope, CO2 emissions, CO2 units, CO2 intensity, CO2 e. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RD11 | SC11—target, reduction, CO2 emissions, refuse, energy use, water use, fuel use, renewable energies | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Result/Index: | 5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 10 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domínguez-Quiñones, M.; Aliende, I.; Escot, L. Assessment of TCFD Voluntary Disclosure Compliance in the Spanish Energy Sector: A Text Mining Approach to Climate Change Financial Disclosures. World 2025, 6, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030092

Domínguez-Quiñones M, Aliende I, Escot L. Assessment of TCFD Voluntary Disclosure Compliance in the Spanish Energy Sector: A Text Mining Approach to Climate Change Financial Disclosures. World. 2025; 6(3):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030092

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomínguez-Quiñones, Matías, Iñaki Aliende, and Lorenzo Escot. 2025. "Assessment of TCFD Voluntary Disclosure Compliance in the Spanish Energy Sector: A Text Mining Approach to Climate Change Financial Disclosures" World 6, no. 3: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030092

APA StyleDomínguez-Quiñones, M., Aliende, I., & Escot, L. (2025). Assessment of TCFD Voluntary Disclosure Compliance in the Spanish Energy Sector: A Text Mining Approach to Climate Change Financial Disclosures. World, 6(3), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030092