1. Introduction

The relationship between climate change and human mobility has been extensively analysed across various fields of research [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, this relationship is complex and nuanced, with studies highlighting that climate change interacts with economic, social, and political factors to influence migration patterns in non-linear and context-specific ways [

5,

6,

7].

While much research has focused on the drivers of migration, comparatively less attention has been given to the characteristics and conditions of the destinations that receive climate migrants (a person or group forced to move due to harmful environmental changes). In this study, we explore the dynamics of significant receiving areas such as informal settlements or slums located on the outskirts of cities. We argue that vulnerability to climate change arises not only from exposure to climate hazards but is deeply shaped by local systemic power relations and structural conditions at both origin and destination [

8,

9]. Our analysis focuses on Latin America, a region marked by high urban inequality and rapid urbanisation. In 2024, the region experienced a record 14.5 million internal displacements, with the majority attributed to climate-related disasters such as floods, droughts, and hurricanes [

10].

The Central American Dry Corridor, encompassing parts of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, exemplifies the region’s susceptibility to climate change. Characterised by recurrent droughts and erratic rainfall patterns, this area significantly impacts agricultural productivity, leading to food insecurity and the displacement of rural populations [

10].

In Latin America, neighbourhoods accommodating populations displaced by climate change are often precarious and marginal, characterised by progressive self-built settlements on urban peripheries. These temporary or semi-permanent settlements emerge as migrants seek integration and aspire to improve their social and economic status [

11]. On the one hand, intensified competition among cities for investment has contributed to the weakening of urban regulatory frameworks and the emergence of state subsidiarity (a governance principle asserting that higher authorities should only perform tasks that cannot be effectively handled at more local levels), which together have facilitated the deregulation of urban management [

12]. On the other hand, the lack of comprehensive urban planning remains a critical barrier to sustainable urban development in the region [

13].

Although informality in slums may seem to provide rapid access for migrants and climate-displaced individuals to urban life, it ultimately acts as a barrier to full socio-economic integration by perpetuating marginalisation [

14]. Despite its significance, informality remains under-recognised as a structural issue affecting migrants’ rights and inclusion.

2. Materials and Methods

This article examines the causes that normalise urban informality by identifying and critically reflecting on the prevalent myths that justify it. Through a comprehensive interdisciplinary literature review, we assess the validity of these reasons and their impact on the integration of climate-displaced populations. The study is structured in three stages: first, analysing the primary reasons or narratives why informality is accepted and maintained in the region, considering diverse disciplinary perspectives and stakeholders; second, evaluating the validity of these reasons or narratives as part of the collective imagination; and, finally, examining how these myths influence the reproduction of marginalised enclaves and limit migrants’ full participation as urban citizens.

2.1. Migration as a Result of Climate Change

According to the 2025 Global Report on Internal Displacement by PreventionWeb, climate-related disasters continue to displace millions worldwide, with significant impacts in vulnerable regions, worsening vulnerabilities in receiving areas [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Migration due to climate change is a critical challenge that needs better integration into development planning, especially in the Global South. Since 1990, the IPCC has warned that human migration could be a major consequence of climate change; as of 2024, evidence has confirmed this in Latin America [

10].

Migration occurs mainly in two forms: slow-onset migration, caused by gradual changes like reduced water availability, biodiversity loss, and soil degradation affecting livelihoods over time; and sudden-onset displacement, triggered by extreme events such as floods, hurricanes, or disease outbreaks, causing the immediate loss of assets and lives. These urgent events often necessitate rapid relocation to collective centres or temporary camps [

10].

The 2001 World Disasters Report estimated 25 million environmental refugees, surpassing war and political refugees globally, though this figure is now seen as outdated. A 2005 UN University projection estimated 200 million climate migrants by 2050, but recent studies highlight wide variability and uncertainty in predictions. Temporary migration as an adaptive response is already observed worldwide, though patterns vary based on migrants’ resources, demographics, poverty, and governance.

Outcomes vary: Rohingya climate migrants settled in flood-prone outskirts of southern Bangladesh [

20,

21], and China relocated up to 350,000 people due to desertification [

22]; conversely, in Northwest Africa, migration may enhance resilience by fostering community flexibility and creativity in climate adaptation [

23]. Despite growing awareness, many Global South countries lack adequate laws and policies to support climate migrants.

Terminology remains controversial; terms like “climate migrants”, “climate displaced persons,” and “climate refugees” imply different legal and political commitments and are inconsistently integrated into policies [

19,

24,

25]. The IOM distinguishes “environmentally induced migrants” (moving primarily for environmental reasons) from “environmentally displaced persons” (moving for environmental and other reasons) [

26,

27].

In certain contexts, such as the settlement of climate migrants in vulnerable urban peripheries, communities face complex interactions between legal pluralism and resistance to exclusionary climate adaptation policies, as observed in Latin America [

19]. This highlights the socio-legal challenges that migrants encounter when settling in precarious environments subjected to environmental hazards.

The challenge posed by climate migrants and displaced populations is recognised in global agendas: the 2030 Development Agenda and SDGs, the Paris Agreement, and the UN Habitat III’s New Urban Agenda. SDGs 11 and 13 emphasise sustainable cities and climate action; Goal 8 protects migrant workers; and Target 10.7 promotes planned migration governance. However, implementation remains challenging without integration into national policies.

2.2. Migrants and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) on Their Way to the Slums of Latin American Cities

Latin America is among the world’s most unequal and climate-vulnerable regions, alongside the Sahara in Africa [

28]. Between 1990 and 2018, the region experienced 288 extreme water-related weather events—a 3% increase over the previous three decades—dominated by floods, storms, and landslides (86%), with droughts accounting for 9%. Temperatures rose by 0.7 °C between 2002 and 2016 compared to 1970–1990 [

29]. Medium-term projections indicate declining agricultural productivity and worsening food security. Notably, the 2015–2016 El Niño event, one of the most intense since 1950, combined with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the warmest recorded period, significantly impacted the region [

30].

These climatic stresses are expected to degrade nutrition, health, and cognitive outcomes, while increasing unemployment and poverty. The region’s capacity to respond is projected to weaken, with direct economic costs estimated at

$100 million annually by 2050 [

31]. Migration is a key adaptive response, occurring immediately after disasters and over the medium term as poverty limits livelihoods. Between 2009 and 2015, natural disasters displaced 8 million people, more than half due to floods, averaging 1.1 million displaced annually. From 2015 to 2050, displacement due to climate change is estimated at 17 million people—around 2.1 million annually—with further increases expected post-2050 [

14].

Concerns about climate change-induced migration are increasing in Latin America. The region acknowledges this challenge through institutions like the Organisation of American States (OAS), the South American Conference on Migration, and the 2014 Brazil Declaration and Action Plan, endorsed by most South American countries. However, both international and internal climate migration remain insufficiently addressed in practice. Although the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) oversees displacement from natural disasters, comprehensive policies to manage climate migration are still limited.

While climate migrants have various destinations depending on departure and arrival contexts, this study focuses on migration to neighbourhoods within Latin American cities [

32]. Urban areas continue to expand, with projections indicating that 84% of the population will live in cities by 2030, rising to 86% by 2050. Although megacities dominated growth in the 20th century, future growth will be fastest in cities with more than one million inhabitants, while smaller towns will still hold the majority of the population [

33]. Migrants settling in cities less affected by climate change are likely to reside in urban slums. Although the proportion of urban dwellers living in slums has generally decreased since the 1990s, stagnation or increases have occurred recently in countries like Bolivia, Colombia, and Mexico. In 2018, around 20% of urban residents lived in slums.

For migrants and climate-displaced individuals, access to employment is critical for integration into the community and the broader economic, political, and social fabric of cities. Urban growth in Latin America’s intermediate towns may be driven more by the need to escape climate-related livelihood losses than by traditional economic opportunities [

34]. This is likely to lead to a repetition of informal settlement patterns—marked by progressive self-construction—this time on the peripheries of intermediate cities rather than capital cities [

35,

36]. Employment also plays a key role in preventing the formation of new, more isolated settlements that could deepen migrants’ marginalisation. In essence, slums serve as destinations for climate migrants, with informality providing the fastest path to social integration [

36].

2.3. Access to Quality Employment in Marginalised Neighbourhoods

Slums originate from residential economic segregation, a process in which the ruling class selects the most desirable neighbourhoods to reside in, thereby making these areas the most expensive and exclusive. Other financial groups occupy neighbourhoods within their affordability [

37]. At the opposite end of this spectrum are the marginalised neighbourhoods, often located furthest from the economic centre of the city, frequently in residual or buffer spaces near open water crossings within the urban area, as well as in historical centres that have inherited poverty structures characteristic of workers from the early Spanish and Portuguese settlements [

38]. Traditionally, migrant groups have settled in slums on the outskirts of cities. These groups often overlook formal property rights and establish their habitats out of necessity, thereby expanding informal urban spaces [

39].

Once established, slums and their extensions acquire distinct characteristics, notably exhibiting the highest poverty levels within the city and creating a significant gap compared to other neighbourhoods. According to the Gini index, urban inequality in Latin America averages 0.43, compared to 0.3 in OECD cities. No major Latin American city reports a Gini index below 0.38 [

39], with capital cities generally presenting the highest levels of inequality [

40].

Poverty within slums is closely tied to labour market conditions, where paid employment constitutes the primary source of income in the region’s cities, followed by self-employment and government transfers. However, slums experience the highest rates of unemployment and underemployment, as well as the lowest wages [

41].

The “active attributes” of slums—characteristics arising from initial residential segregation and becoming entrenched over time—shape residents’ ability to access and maintain better jobs that enable social mobility. Among these attributes, mobility conditions, the quality of education, and the availability of essential services are key factors influencing employment opportunities and job retention [

42,

43,

44].

Nearly a quarter of the urban population, mainly in peripheral areas, spends over an hour commuting to work. For 25% of commuters, mobility conditions are poor or very poor [

45]. While public transport is approximately three times less expensive annually than private transport, it accounts for 25% of the income for the lowest-income groups compared to just 5% for the wealthiest [

46]. Given this, commuting times and costs often negate the benefits of minimum-wage employment [

47]. Additionally, underinvestment in education within slums perpetuates social and economic gaps [

48,

49,

50].

Basic services such as electricity, sanitation, and waste collection remain significantly poorer in slums than in other city areas [

51]. Moreover, housing access poses additional challenges for these populations, often relying on progressive self-construction or precarious rental arrangements [

52].

The persistent challenges related to mobility, essential services, and education largely stem from deficiencies in urban planning, insufficient infrastructure investment, and public policies that inadequately address residents’ opportunities while sustaining the exclusivity of elite social capital [

12,

13,

53].

Although some successful interventions exist to improve the quality of life in marginalised neighbourhoods [

54], these efforts remain insufficient due to limited budgets, which necessitate prioritising needs. Residents often lack the capacity to influence the overall budget allocated to their neighbourhoods or to determine the actions most needed. Consequently, their perspectives on interventions are frequently overlooked, either directly or indirectly. Research by [

55] illustrates that, in ten analysed large-scale slum interventions across the region, neighbourhood considerations were systematically neglected. The dismissal of slum residents’ voices in decisions affecting them often occurs through performative participation involving various stakeholders. Cooperative urban governance models sometimes result in participatory leaders shaping community opinions [

56] or the implementation of global management mechanisms [

57] that remain alien to local neighbourhood cultures.

2.4. The Possibility of Influencing Public Policy from Marginalised Neighbourhoods

The potential for political advocacy by marginalised neighbourhoods to influence and enhance public interventions largely depends on their capacity to engage in meaningful dialogue. However, existing civic participation systems are often designed by an elite that controls access to improved budgets and decision-making processes, leaving residents of marginalised neighbourhoods uncertain about how to effectively participate [

58]. Moreover, advocacy efforts are further constrained by limited community life and weak collective action, conditions that stem from a pervasive lack of trust among slum dwellers. This mistrust is rooted in the diverse and often precarious contexts in which these communities live [

59,

60]. The state frequently fails to enforce fundamental rules of coexistence, and these neighbourhoods tend to experience the highest levels of violence, crime, and insecurity within the city [

61].

Residents of slums are often viewed with suspicion by the rest of the urban population, based on stereotypes that (1) slums shelter individuals whom no other community will accommodate; (2) slums are inhabited exclusively by people living in poverty; and (3) slum residents are destined to remain impoverished. Such stigmatisation results in exclusion from employment opportunities, as employers commonly disqualify applicants from these areas, while economic elites define themselves in opposition to slum residents [

61,

62,

63].

Within slums, new subcultures emerge, developing their own communication codes, behaviours, and social norms. While these subcultures create a sense of identity and belonging for residents, they simultaneously restrict access to the elite’s social capital—resources essential for upward social mobility [

64].

2.5. Informality as an Active Feature of Slums

Within the context of structural discrimination in the labour market, the slum economy naturally gravitates towards informality. Informal workers are those engaged in unregistered economic activities that lack legal recognition and protection by authorities [

65]. Informality is predominantly a characteristic of the lower income deciles.

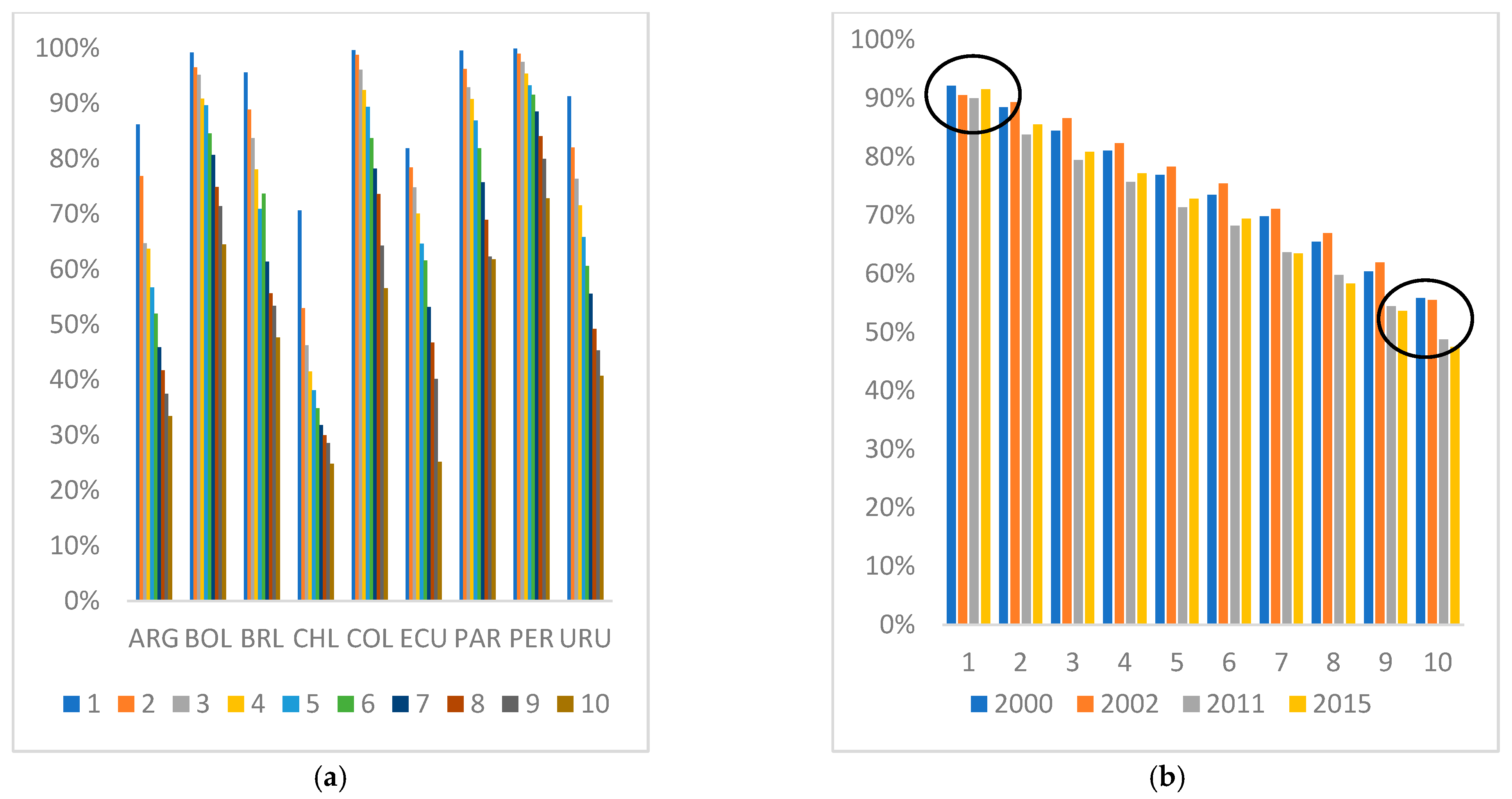

Figure 1 illustrates that informality declines as wealth increases. In the lowest decile (decile 1), the average informality rate reaches approximately 85% of workers, while the overall average stands at 50%.

Figure 2 further confirms that informality is a defining feature of the lower income groups. Notably, the lowest income groups experience the smallest reductions in informality when it decreases overall and, conversely, show the largest increases when informality rises. Over the period from 2000 to 2015, decile 1 remains the only income group with comparable levels of informality, reflecting persistent structural challenges (See the black circles where you can compare the behaviour of decile 1 (highest) with decile 10 (lowest).

As informality is closely associated with precariousness and poverty, the characteristics of the lowest income deciles closely mirror those of informal groups. Analyses of data from Peru and Brazil reveal that non-compliance with formal regulations predominantly affects low-skilled workers and women. In Chile, informality disproportionately impacts Indigenous communities and rural areas. In Argentina, informality is a prevalent feature among small firms whose less educated owners lack access to credit [

66].

Geographically, the highest levels of informality are observed in rural areas and urban slums—the very locations where poor migrants from other regions tend to settle. For migrants arriving in slums, informality is often perceived as the natural or only viable income-generating option. These individuals accept working conditions considered the worst, often rejected by others. Some may even relinquish all formal rights as individuals, which can lead to involvement in illicit markets, including drugs and human trafficking [

67].

Although informality often carries an aura of provisionality, it not only fails to dismantle the barriers imposed by formality but actively reinforces them. The informal system operates in opposition to formal structures, and evolving from informality would require adopting practices that foster a distrust of formal groups and restrict participation. While the goods and services provided through informal mechanisms are widely utilised and can become normalised, the state of informality remains rejected alongside formal structures [

68].

Informality is thus another active attribute of slums that constrains social mobility, although it is not typically recognised as such. It is generally accepted that, in slums, barriers to sustainable access to better employment include mobility conditions, the quality of education, and the availability of basic services. These factors should be enhanced to promote social mobility. In contrast, informality is not widely acknowledged as an active barrier; yet, it is broadly accepted by both rights holders and duty bearers, which contributes to a perceived lack of urgency to reduce it. This study critically examines the reasons that justify informality’s persistence.

In practice, formalisation laws are predominantly enforced for large companies and the public sector. The lax enforcement by executive and judicial branches encourages voluntary formalisation rather than mandating compliance [

69]. This laxity is particularly surprising given research demonstrating that strengthening control systems and implementing targeted measures can significantly reduce informality [

70,

71,

72].

Recognising acceptance as the initial step toward normalising informality, this paper poses a central question: why is informality tolerated, and, more importantly, what consequences might such tolerance entail within the context of marginal urban growth driven by increased climate migration?

To address this question, we undertake a critical reflection based on a comprehensive literature review regarding the causes of informality from the perspective that justifies it, assessing their validity—myth or fact. The study is conducted in two stages. First, we analyse the primary reasons why informality is accepted in the region and the motivations citizens have for maintaining it. We do not exclude any causes based on their disciplinary origin or the groups that hold them; thus, both formal and informal stakeholders are considered. In the second stage, we evaluate the extent to which the reasons justify informality.

3. Results

3.1. The Myths That Justify Slum Informality

Informality in Latin American slums is commonly justified by four prevailing myths: (1) the low levels of regional productivity [

73]; (2) concessions made by the ruling class to enable excluded groups to survive [

74]; (3) the capacity of marginalised neighbourhoods to generate income outside formal legal frameworks, which underpins their social capital; and [

75] (4) the limited perceived benefits of formalisation [

76,

77,

78].

(1) Due to truncated industrialisation, the Latin American economy is characterised by the coexistence of a modern sector with productivity levels comparable to high-income countries, alongside a traditional sector marked by inefficiency and low added value. The modern sector predominantly absorbs skilled labour, forcing unskilled workers into the traditional sector, which fails to generate sufficient profits to cover the costs associated with formalisation. Individuals unable to secure employment even within the informal traditional labour market often resort to self-employment [

73]. Consequently, informality is viewed as a natural stage in the region’s economic development trajectory, expected to persist until productivity levels approach those of high-income countries, at which point formalisation across all economic activities may become feasible [

73].

(2) From the perspective of the ruling class, informality is often regarded as a temporary mechanism necessitated by the exclusion inherent in slums [

79]. Considering that average incomes in these areas fall below the value of the basic basket of goods, it is rational for residents to avoid the additional costs of legalisation [

80] and taxation [

81]. Since informal workers lack the rights associated with formal market participation [

82], evading the regulations and obligations of formalisation can present an economic advantage [

74,

77,

83].

(3) Within slums, informality is also conceptualised as a form of social capital. Residents are acutely aware of their exclusion from the “private club” of formalisation [

84], as they often lack the knowledge and skills to navigate formal bureaucratic settings [

85], and formal institutions frequently fail to accommodate them. In response, slum dwellers establish informal structures that develop their own languages and social codes, inaccessible to outsiders. The absence of formal training and bureaucratic requirements limits participation in formal economic systems but creates opportunities within informal economies, which ultimately foster a sense of belonging and collective identity [

75,

86,

87].

(4) The formal system itself offers limited incentives for formalisation. The marginal costs of formalising economic activities are often prohibitively high, while the benefits remain minimal. Informal residents typically have access only to basic public services of poor quality [

88], from which they do not derive significant benefit since their individual contributions cannot improve these services [

89]. Furthermore, informality is historically justified by the longstanding denial of opportunities to improve living standards [

90] and by widespread corruption scandals within the state [

91]. Those attempting to formalise face complex, costly, and often misaligned bureaucratic processes that fail to reflect the realities of the Latin American economic context [

76,

77,

78,

92].

These four myths represent traditional justifications that effectively condemn climate migrants—who contribute to the expansion of slums—to social exclusion. Such myths hinder their active participation in urban life, limit the development of available human capital, and enlarge spaces susceptible to illegality. They also weaken the demands of rights holders for policies aimed at reducing informality and provide duty bearers with a rationale to deprioritise informality in public policy agendas.

In the subsequent sections, we critically assess whether these reasons genuinely account for the actions of rights holders and duty bearers or if they function predominantly as entrenched beliefs within the urban culture of the region.

3.2. Debunking the Myths That Justify Informality

The four traditional justifications for informality presented in the previous section are challenged by the following arguments:

(1) Empirical evidence demonstrates that informality is not an inevitable or natural component of the Latin American economic structure, nor will it automatically decline as productivity increases. Studies such as [

93,

94,

95] indicate that informality functions as a negative externality rather than a structural economic feature. Accordingly, informality requires deliberate and effective public policies to mitigate its detrimental impacts. As noted by [

96], climate migration, now recognised as a pressing challenge, must be integrated into broader urban development strategies that promote inclusive and sustainable progress.

(2) The perception of informality as a temporary survival strategy serves primarily as a justification for the persistent absence of structural measures guaranteeing the right to formality. This perception perpetuates a misleading sense of social stability, framed as the highest attainable peace. Such framing functions as a political tactic to impede meaningful structural reforms in public policy that could address the active factors restricting social mobility in slums. Consequently, this perpetuates a scenario of relative social calm that suppresses demands for justice from impoverished communities.

The lack of public policy intervention aimed at eradicating informality coincides with insufficient urban planning designed to tackle the active characteristics of slums and prevent urban stratification. This deficiency is often justified by the neoliberal notion of “less state but more efficient” governance [

97,

98], a legacy of the Washington Consensus that has influenced public policy since the 1980s [

52]. A comprehensive urban planning approach, aligned with positive fiscal policies, would enable climate migrants to claim their right to the city [

36]—a right currently denied to many.

(3) In South America, informality creates a dichotomy regarding access to essential public services such as health and education. Informal residents typically do not pay taxes -despite multiple efforts by various governments, yet they are the primary users of these public services. Their lack of fiscal contribution undermines their legitimacy in demanding improvements to these often inadequate services, effectively rendering them users without full access to their constitutional rights. Conversely, those in formal employment contribute taxes supporting public health and education but frequently do not utilise these services. Despite this, they remain sceptical that increased taxation would substantially improve the quality of public services to their benefit [

98].

This analysis highlights the myth that informality facilitates the exercise of fundamental rights, such as access to health and education. In reality, informality often entails the forfeiture of these rights. Formalisation directly enables access to essential services and protections. Moreover, as informality hinders social mobility, achieving self-financing of such services will pose significant challenges for climate migrants settling in South American cities.

3.3. How Myths Justifying Informality Affect the Integration of Climate Migrants

While the flexibility, diversity, and creativity of informal communities can aid in coping with climate stress [

23], informality itself—and the myths that sustain it—should not be romanticised as adaptive strategies. Rather, informality often results in increased vulnerability due to the absence of guaranteed rights and protections.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recognises economic inclusion—defined as the opportunity to work and earn an income—as fundamental for migrants and displaced persons to rebuild their lives with dignity and peace after fleeing conflict or persecution [

99]. Employment also facilitates deeper integration into host communities by enabling displaced individuals to contribute positively and participate more fully in social and economic life.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) identifies the informal workforce as particularly vulnerable due to their lack of legal recognition and protection within regulatory frameworks. Informality exacerbates vulnerabilities through multiple channels, including the following:

Little or no access to legal or social protections;

Inability to enter into formal contracts or secure property rights;

Difficulties in organising effective representation and ensuring that their voices are heard to protect their work;

Limited or inadequate access to infrastructure and public subsidies;

Dependence on informal and often exploitative institutional arrangements for information, market access, credit, training, or social security;

Vulnerability to the discretionary attitudes of public authorities and the strategic behaviours of large formal enterprises;

Employment in precarious jobs offering low, irregular, and insecure incomes;

Competitive disadvantages arising from the lack of leverage that formal economy actors can exert, undermining fair and efficient market access;

Exposure to misinterpretation of informal activities as criminal by authorities, leading to harassment, including bribery, extortion, and repression [

100].

Although the ILO acknowledges that there is no simple causal relationship between informal work and poverty—or formal work and escape from poverty—it highlights that a significantly higher proportion of impoverished individuals are engaged in informal employment compared to formal employment [

100]. From a broader perspective, the ILO emphasises that formalisation embodies several critical aspects of labour security, including the following:

Labour market security, supported by favourable job opportunities and effective macroeconomic policies;

Employment security, ensuring protection against arbitrary dismissal and regulated hiring and firing practices, compatible with economic dynamism;

Job security, involving the establishment and consolidation of a professional career and a sense of belonging through self-improvement;

Occupational safety, including protection from workplace accidents and diseases via health and safety regulations;

Security of skills development, providing opportunities for acquiring and maintaining professional qualifications through innovative training, apprenticeships, and on-the-job learning;

Income security, guaranteeing adequate and stable earnings;

Security of representation, safeguarding the right to collective bargaining through trade unions, employer organisations, and institutions facilitating social dialogue.

These dimensions highlight the crucial role that formalisation plays in ensuring decent work conditions and social protection, which are essential for the successful integration of climate migrants into urban economies.

4. Discussion

The population of the South American region continues to be predominantly young, representing a significant potential demographic dividend. Human capital, therefore, emerges as the critical factor in overcoming the longstanding obstacle of insufficient productivity, which continues to limit improvements in the quality of life across the region. However, realising this potential requires not only investment in education and skills development but also the removal of structural barriers that prevent the full utilisation and enhancement of human capital, particularly among marginalised and migrant populations.

In scenarios where migrants and displaced individuals are recognised as active agents and contributors rather than mere problems, migration ceases to be framed solely as a challenge. Instead, it becomes an opportunity to drive urban development and social inclusion. For this positive framing to be realised, it is essential to dismantle the multiple constraints that hinder the optimisation and growth of human capital among migrants. Specifically, in the context of climate migration—predominantly affecting informal settlements and slums—policymakers and stakeholders must urgently address the systemic conditions of exclusion that are intrinsically linked to urban peripheries and marginalisation.

Informality, historically associated with exclusion and precariousness in slums, remains widely accepted both by rights holders—residents themselves—and by duty bearers—public authorities and policymakers. This acceptance is often rationalised through persistent myths: that Latin America’s low productivity justifies informality; that the ruling class tolerates informality as a concession to allow excluded groups to survive; that slum dwellers’ capacity to generate income outside formal legal frameworks supports their social capital; and that the benefits of formalisation are limited or negligible.

Our analysis reveals that these justifications are less empirical realities and more inherited myths, adapted and perpetuated by diverse social actors to maintain the status quo. Informality is not an inevitable or natural response to economic systems; rather, it is a symptom of systemic policy failures. It emerges and persists within a context of absent or ineffective public policies, which sustain a deceptive and ultimately unsustainable social peace—one that denies rights to certain citizens and relegates them to positions of inferiority relative to others. This exclusion perpetuates cycles of underdevelopment by preventing equitable access to genuine opportunities for social and economic progress.

By limiting the participation of marginalised groups in the economic, political, and social life of the city, informality serves as a mechanism that sustains an inadequate welfare state. It restricts the development and utilisation of human capital essential for elevating the quality of life not only for those directly affected but for society as a whole. Furthermore, informality exacerbates urban inequality by entrenching spatial and social segregation, which in turn hampers social mobility and deepens poverty.

To overcome these challenges, it is imperative to move beyond superficial policy responses that merely tolerate informality. Instead, comprehensive and inclusive strategies are required—ones that integrate climate migrants and informal workers into formal economic, social, and political systems. This includes improving access to quality education, infrastructure, health services, and decent employment opportunities, alongside reforms to urban governance that foster meaningful civic participation and protect fundamental rights.

In this light, climate migration should be understood as a catalyst for progressive urban transformation rather than an isolated burden. Recognising and actively integrating migrants’ human capital can stimulate innovation, resilience, and inclusive growth, provided that structural inequalities are addressed and that the myths perpetuating informality are debunked.

5. Conclusions

This study critically examines the prevailing myths surrounding informality and highlights the significant socioeconomic challenges faced by climate-displaced populations in Latin American cities. However, it is important to acknowledge that the data utilised in this research is limited and may not fully represent the current dynamics of climate-induced displacement.

Recent reports provide updated figures and insights into the scale of climate-induced displacement:

IDMC 2025 Global Report on Internal Displacement: As of the end of 2024, 83.4 million people were living in internal displacement worldwide, with 9.8 million displaced by disasters, including climate-related events.

UNHCR Americas Factsheet (May 2025): In 2024, severe flooding in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, affected over 2.3 million people, displacing more than 422,000 individuals.

The emerging scientific literature emphasises the complex interplay of systemic power relations, governance challenges, and local adaptation capacities in shaping migration and integration outcomes. Recent studies by Otero-Cortés et al. [

101], and Acevedo et al. [

102]. provide valuable insights into these dynamics in Latin America.

While the datasets and analyses from recent reports offer a more accurate reflection of current trends in climate-induced displacement, this study serves as a foundational reference that highlights the gaps in previous data and perspectives. It brings attention to myths and assumptions that have not been adequately challenged in earlier research.

Future research should aim to integrate the updated data and frameworks from recent reports to deepen understanding and enhance the validity of recommendations for inclusive urban planning and social policy. This study provides a critical starting point by deconstructing entrenched myths with existing data, setting the stage for evidence-based policy development that benefits climate migrants and host communities alike.

Another significant contribution of this study is its ability to observe how both historical data variables and newly collected variables from recent studies can illustrate the evolution of myths surrounding informality. This evolution may manifest in several ways:

Persistence: Some myths remain unchanged, indicating that other factors continue to influence the construction of these myths.

Mutation or Expansion: Existing myths may evolve or new ones may emerge, adding new dimensions to the discourse.

Disappearance: In the best-case scenario, certain myths may dissipate, leading to a more coherent reflection aligned with urban planning that facilitates dignified housing in these neighbourhoods.

Another promising avenue for future research is the examination of specific cases at the meso- (national) or micro- (city-specific) levels, where the dynamics of myths surrounding informality can be observed in relation to urban planning in these neighbourhoods. Such studies could involve collecting data similar to that presented in this article, alongside an analysis of the regulatory frameworks of each country or city. For instance, research in cities like Tegucigalpa, Honduras, has utilised machine learning techniques to map potential informal settlement areas, providing valuable insights into urban informality. Additionally, São Paulo, Brazil, has developed flood risk maps using hydrological and mobility data, which can inform urban planning decisions in informal settlements. These case studies illustrate how localised research can shed light on the intersection of myths, informality, and urban planning, offering a foundation for more targeted and effective policy interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M.; methodology, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M.; validation, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M.; formal analysis, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M.; investigation, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M.; resources, S.H.O.; data curation, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.O.; writing—review and editing, S.H.O., A.M.D.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding for our research was provided by the Universidad de Las Américas -Internal Call for Research Projects No. XV. We have access to internal research funds.

Data Availability Statement

All sources referenced in this review article are publicly accessible and can be consulted by readers through the provided citations and links. This manuscript is based entirely on a comprehensive synthesis of existing literature, reports, and publicly available datasets. No new primary data were created or analyzed in this study. Therefore, there are no additional datasets generated or analyzed that require archiving.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Cottrell, A.; King, D.; Islam, M.N. Environmental Migrants in Bangladesh: A Case Study on Climatic Change Hazards in the Southwestern Coastal Area. In Bangladesh I: Climate Change Impacts, Mitigation and Adaptation in Developing Countries; Islam, M.N., van Amstel, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemenne, F. Why the numbers don’t add up: A review of estimates and predictions of people displaced by environmental changes. Global Environ. Change 2011, 21, S41–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, S. The role of environmental degradation in population displacement. Environ. Change Secur. Proj. Rep. 1998, 4, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, K.; Gulati, S.C. Environmental degradation and population movements: The role of property rights. Environ. Resour. Econ. 1997, 9, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, A.G.; Sarmiento, M.R.; Hernández, J.G.V. Políticas públicas participativas, desplazamiento forzado ambiental y cambio climático. Rev. Virtual Univ. Católica Del. Norte 2017, 51, 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.G.V.; Fajardo, A.M.A.; Sarmiento, M.R. Desafíos de la Justicia Ambiental Y El Acceso a la Justicia Ambiental en El Desplazamiento Ambiental Por Efectos Asociados Al Cambio Climático. Luna Azul 2015, 41, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, C.E.; Suescún, J.I.S. Los desplazados ambientales, más allá del cambio climático. Un debate Abierto. Cuad. Geográficos 2011, 49, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Lazrus, H. Perspectives on vulnerability to climate change and migration in Tuvalu. Link. Environ. Change Migr. Soc. Vulnerability 2009, 32, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J. Vulnerability does not just fall from the sky: Toward multi-scale pro-poor climate policy. In Handbook on Climate Change and Human Security; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2025 Global Report on Internal Displacement. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2025/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Giglia, A. El habitar y la cultura: Perspectivas teóricas y de investigación. Anthr. Barc. 2012, 24, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Daude, C.; Fajardo, G.; Brassiolo, P.; Estrada, R.; Goytia, C.; Sanguinetti, P.; Álvarez, F.; Vargas, J. RED 2017. Crecimiento Urbano y Acceso a Oportunidades: Un Desafío para América Latina; CAF: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CG/LA. Infraestrucutre. Available online: https://www.cg-la.com/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Rigaud, K.K.; de Sherbinin, A.; Jones, B.; Bergmann, J.; Clement, V.; Ober, K.; Schewe, J.; Adamo, S.; McCusker, B.; Heuser, S.; et al. Groundswell; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 10, p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, T. Climate change creates a new migration crisis for Bangladesh. Natl. Geogr. Mag. 2019. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/climate-change-drives-migration-crisis-in-bangladesh-from-dhaka-sundabans (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Global Environ. Change 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.R.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Mach, K.J.; Abdrabo, M.A.; Adger, W.N.; Anokhin, Y.A.; Anisimov, O.A.; Arent, D.J.; Barnettet, J.; et al. Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects; Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Climate change impacts and adaptation assessment in Bangladesh. Clim. Res. 1999, 12, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, E.; Falla, A.M.V.; Boyd, E. The law of the four poles: Legal pluralism and resistance in climate adaptation. Law. Soc. Rev. 2025, 59, 50–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, R.; Dolšak, N.; Prakash, A.; Reinsberg, B. Willingness to help climate migrants: A survey experiment in the Korail slum of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.P.; Ilina, I.N. Climate change and migration impacts on cities: Lessons from Bangladesh. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassiola, J. China’s Environmental Crisis: Domestic and Global Political Impacts and Responses; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffran, J.; Marmer, E.; Sow, P. Migration as a contribution to resilience and innovation in climate adaptation: Social networks and co-development in Northwest Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbotko, C.; Lazrus, H. The first climate refugees? Contesting global narratives of climate change in Tuvalu. Global Environ. Change 2012, 22, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeva, M.; Salevska-Trajkova, V. Climate Refugees or Climate Migrants: How Environment Challenges the International Migration Law and Policies; University American College Skopje: Skopje, North Macedonia, 2020; pp. 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIM. Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Evidence for Policy (MECLEP) Glossary. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/meclep_glossary_en.pdf?language=en (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Grupo de Trabajo del Grupo Sectorial Global de Protección. Manual para la Protección de los Desplazados Internos. Available online: https://www.acnur.org/5c6c3ae24.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- ND-Gain Country. Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index (ND-Gain). Universidad de Notre Dame. 2017. Available online: https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Ibarra, A.B.; Samaniego, J.; Peres, W.; Alatorre, J.E. La Emergencia del Cambio Climático en América Latina y el Caribe:¿ Seguimos Esperando la Catástrofe o Pasamos a la Acción? Cepal: México City, México, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R.; Zambrano, E.; López, J.J.N.; Hernández, J.; Costa, F. Evolución, vulnerabilidad e impactos económicos y sociales de El Niño 2015-2016 en América Latina. Investig. Geogr. 2017, 68, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saget, C.; Vogt-Schilb, A.; Luu, T. El Empleo en un Futuro de Cero Emisiones Netas en América Latina y el Caribe; Inter-American Development Bank and International Labour Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetzel, R.; Ruiz, S. Movilidad Humana, Desastres Naturales y Cambio Climático en América Latina. De la Comprensión a la Acción; RED-LAC und RED GADer-ALC de la Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, por encargo del Ministerio Federal de Cooperación Económica y Desarrollo: Quito, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NNUU. World Urbanization Prospects. 2021. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Patiño, B.B.; Olarte, S.H. La clase dominante como determinante de la forma de Quito. Bitacora Urbano Territ. 2017, 27, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, F. Las nuevas tendencias de la urbanización en América Latina. La ciudad construida. Urban. En. América Lat. 2001, 1, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Harve, D. The Social Construction of Space and Time: A Relational Theory. Geogr. Rev. Jpn. Ser. B 1994, 67, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.F.; Zapata, M.C. Mercantilización y expansión de la inquilinización informal en villas de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Rev. INVI 2018, 33, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The production of space (1991). In The People, Place, and Space Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Jordán, R. Desarrollo Sostenible, Urbanización y Desigualdad en América Latina y el Caribe: Dinámicas y Desafíos para el Cambio Structural; Cepal: México City, México, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Busso, M.; Messina, J. La Crisis de la Desigualdad: América Latina y el Caribe en la Encrucijada; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Olarte, S. La desigualdad en los tiempos de crisis. El caso sudamericano. J. Global Compet. Governability 2021, 15, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITF (International Transport Forum). Developing Accessibility Indicators for Latin American Cities; ITF: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, F.; Goicolea, I. “We believe in you, like really believe in you”: Initiating a realist study of (re)engagement initiatives for youth not in employment, education or training with experiences from northern Sweden. Eval. Program. Plan. 2020, 83, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, L.; Cecchini, S.; Morales, B. Social Programmes, Poverty Eradication and Labour Inclusion. Lessons from Latin America and the Caribbean (30 May 2019); United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CAF. Observatorio de Movilidad Urbana. Available online: https://www.caf.com/es/conocimiento/datos/observatorio-de-movilidad-urbana/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Rivas, M.E.; Serebrisky, T.; Suárez-Alemán, A. ¿ Qué tan Asequible es el Transporte en América Latina y el Caribe? Nota Técnica del BID; Inter-American Development Bank and International Labour Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, E.A.; Powell, A.; Serebrisky, T. From Structures to Services: The Path to Better Infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean; Felipe Herrera Library (Inter-American Development Bank): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CAF. Construcción de Ciudades más Equitativas; ONU Hábitat-CAF: Bogotá, Columbia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaztman, R. Reflexiones en torno a las metástasis de las desigualdades en las estructuras educativas latinoamericanas. Cad. Metrópole 2018, 20, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, I.E. Estudio sobre la Calidad de la Educación en Escuelas de Barrios Periféricos de Santiago de Chile:¿ Una Justicia ante la Marginalización Social? Rev. Int. Educ. Para Justicia Soc. 2020, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrisky, T. Megaciudades e Infraestructura en América Latina: Lo que Piensa su Gente; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Exclusión Laboral por Movilidad. El caso de Quito (Ecuador). Ciudad. Y Territ. Estud. Territ. 2020, 52, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñetón-Santa, G.; Gutiérrez-Loaiza, A. Pobreza y enfoque de capacidades: Un caso de estudio en el programa de superación de la pobreza extrema en Medellín, Colombia. Entramado 2017, 13, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, I. De periferia a ciudad consolidada: Estrategias para la transformación de zonas urbanas marginales. Revista Bitácora Urbano Territorial 2005, 9, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F.; Rodriguez, A. Neoliberal Urbanization in Europe: Large–Scale Urban Development Projects and the New Urban Policy. Antipode 2002, 34, 542–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, J.P. Treinta objeciones a Horacio Capel. Scr. Nova: Rev. Electrónica De. Geogr. Y Cienc. Soc. 2011, 15, 1. Available online: https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/ScriptaNova/article/view/3414 (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Parnreiter, C. Formación de la ciudad global, economía inmobiliaria y transnacionalización de espacios urbanos: El caso de Ciudad de México. EURE 2011, 37, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R. Los centros históricos y el desarrollo inmobiliario: Las contradicciones de un negocio exitoso en Santiago de Chile. Scr. Nova Rev. Electrónica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2010, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Janoschka, M. Geografías urbanas en la era del neoliberalismo. Una conceptualización de la resistencia local a través de la participación y la ciudadanía urbana. Investig. Geogr. 2011, 76, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogel, V.; Silva, I. Marginalidad. In Promoción Popular y Neo-Marxismo; CEDIAL: Bogotá, Colombia, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- De Duren, N.L. Barrios Mejorados y Seguros; Felipe Herrera Library (Inter-American Development Bank): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauder, H. Culture in the labor market: Segmentation theory and perspectives of place. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2001, 25, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J.S. Carrots and Sticks: Pay, Supervision, and Turnover. J. Labor. Econ. 1987, 5, S136–S152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaztman, R. Seducidos y abandonados: El aislamiento social de los pobres urbanos. Rev. CEPAL 2001, 75, 171–189. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/entities/publication/8678e36b-5acc-4e93-872e-a54376b48b71 (accessed on 6 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- ILO. Employment, Incomes and Equality; A Strategy for Increasing Productive Employment in Kenya; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, U.; Belser, P.; Oelz, M.; Ranjbar, S. Minimum wage coverage and compliance in developing countries. Int. Labour Rev. 2013, 152, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R.; Tuomala, M. Relativity, Inequality, And Optimal Nonlinear Income Taxation. Int. Econ. Rev. 2013, 54, 1199–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garganta, S.; Gasparini, L. The impact of a social program on labor informality: The case of AUH in Argentina. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 115, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronconi, L. Enforcement of labor regulations in developing countries. IZA World Labor. 2019, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, L.; Syrett, S. Out of the shadows? Formalisation approaches to informal economic activity. Policy Politi 2007, 35, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibben, P.; Williams, C.C. Varieties of Capitalism and Employment Relations: Informally Dominated Market Economies. Ind. Relat. J. Econ. Soc. 2012, 51, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.C. Out of the shadows: A classification of economies by the size and character of their informal sector. Work Employ. Soc. 2013, 28, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebisch, R.; Cabañas, G.M. El Desarrollo Económico De La América Latina Y Algunos De Sus Prin-Cipales Problemas. Trimest. Econ. 1949, 16, 347–431. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20855070 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Hirschman, A.O. La Estrategia Del Desarrollo Económico. Trimest. Econ. 1983, 50, 1331–1424. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23395856 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Lewis, W.A. Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, J.I.; Ortiz, C.H.; Castro, J.A. Una teoría general sobre la informalidad laboral: El caso colombiano. Econ. Desarro. 2006, 5, 213–273. [Google Scholar]

- Tokman, V. Las relaciones entre los sectores formal e informal. Rev. CEPAL 1978, 1978, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. En Torno a la Informalidad: Ensayos Sobre Teoría y Medición de la Economía no Regulada; Flacso: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, A. The Moral Significance of Class; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tenjo, J. Informalidad, ventas ambulantes y mototaxismo:¿ por qué abundan y cómo tratarlos. Razón Pública, 3 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tokman, V.E. De la informalidad a la modernidad. Economia 2001, 24, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, K. The Informal Economy. Camb. Anthropol. 1985, 10, 54–58. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23816368 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Loayza, N.; Palacios, L. Economic Reform and Progress in Latin America; World Bank: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Enste, D. Hiding in the Shadows: The Growth of the Underground Economy: The Growth of the Underground Economy; International Monetary Fund (IMF): Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, A.; Macdonald, F. Thinking about informality: Gender (in)equality (in) decent work across geographic and economic boundaries. Labour Ind. J. Soc. Econ. Relat. Work 2018, 28, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K.A. Routes to the Informal Economy in New York’s East Village: Crisis, Economics, and Identity. Sociol. Perspect. 2004, 47, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canelas, C. Informality and poverty in Ecuador. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 53, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza, N. Causas y consecuencias de la informalidad en el Perú. Rev. Estud. Económicos 2008, 15, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gërxhani, K.; Koster, F. ‘I am not alone’: Understanding public support for the welfare state. Int. Sociol. 2012, 27, 768–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancour, G.S. La informalidad laboral: Causas generales. Equidad Desarro. 2014, 22, 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R.; Ronconi, L. Enforcement matters: The effective regulation of labour. Int. Labour Rev. 2018, 157, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.A. The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies; WIEGO: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beccaria, L.A.; del Maurizio, R.L. Un análisis dinámico de los flujos de entrada a la formalidad en América Latina. Rev. Econ. Labor. 2018, 18, 8–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F.; Buehn, A.; Montenegro, C.E. Shadow Economies All Over the World: New Estimates for 162 Countries from 1999 to 2007. In Handbook on the Shadow Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. The Economic Lives of the Poor. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ILO. International Labour Organization’s XIV th American Regional Meeting Concludes Its Work; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno, M.A.; Portes, A. The informal economy in the shadow of the state. In Out of the Shadows: Political Action and the Informal Economy in Latin America; Penn State Press: University Park, PA, USA, 2006; Volume 2006, pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados. Medios de vida e Inclusión Económica. Available online: https://www.acnur.org/medios-de-vida-e-inclusion-economica (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- ILO/Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2002 Labour Overview; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Cortés, A.; Acosta, K.; Arango, L.E.; Aristizábal, D.; Ávila-Montealegre, Ó.; Becerra, Ó.; Fernández, C.; Flórez, L.A.; Galvis-Aponte, L.A.; Grajales, Á.; et al. Nueva evidencia sobre la informalidad laboral y empresarial en Colombia. Ensayos sobre Política Económica 2025, 108, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, I.; Castellani, F.; Lotti, G.; Székely, M. Informalidad en los Tiempos del COVID-19 en América Latina: Implicaciones y Opciones de Amortiguamiento; IDB Working Paper Series, No. IDB-WP-01232; IDB: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).