Human Rights-Based Approach to Community Development: Insights from a Public–Private Development Model in Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

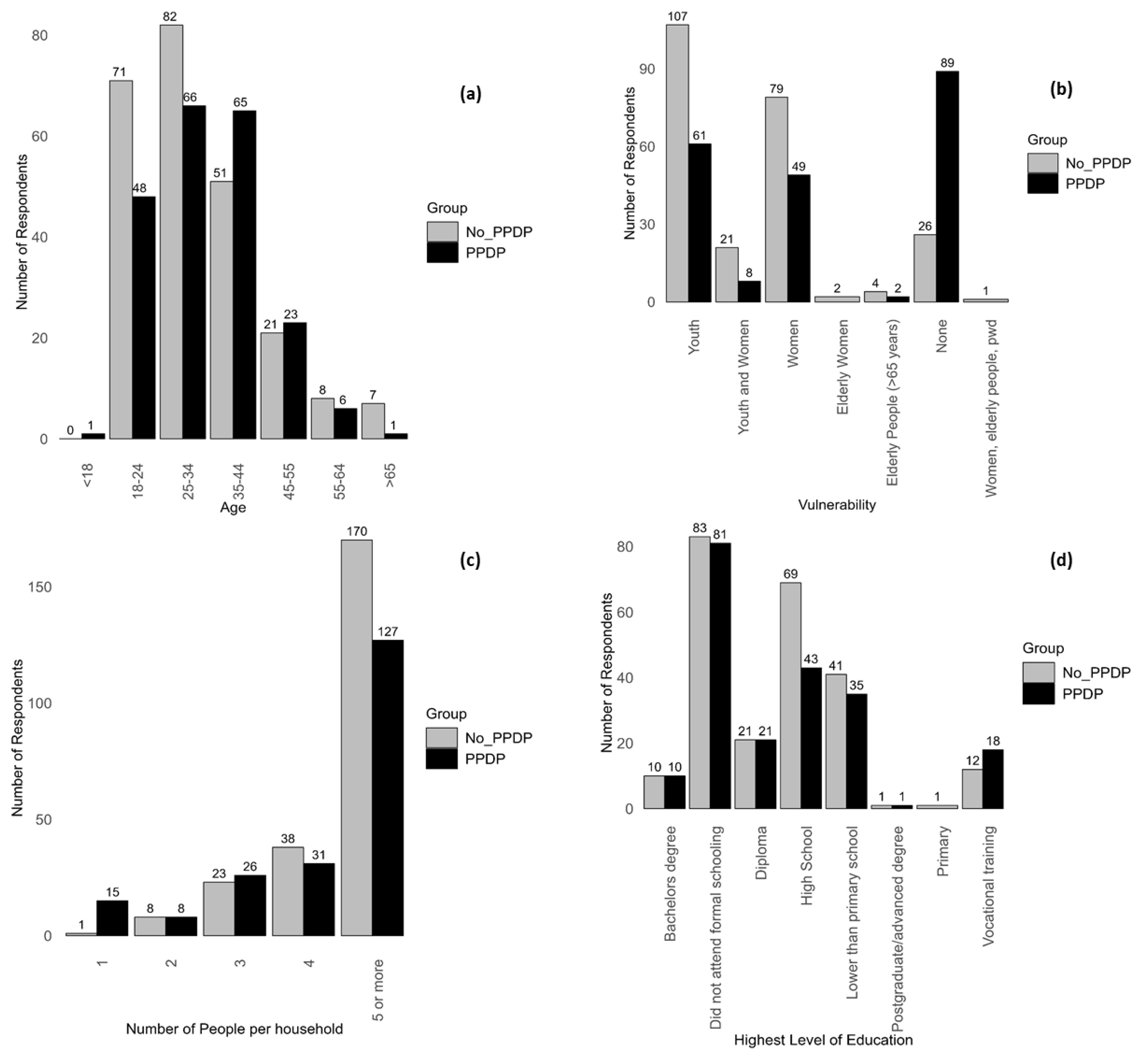

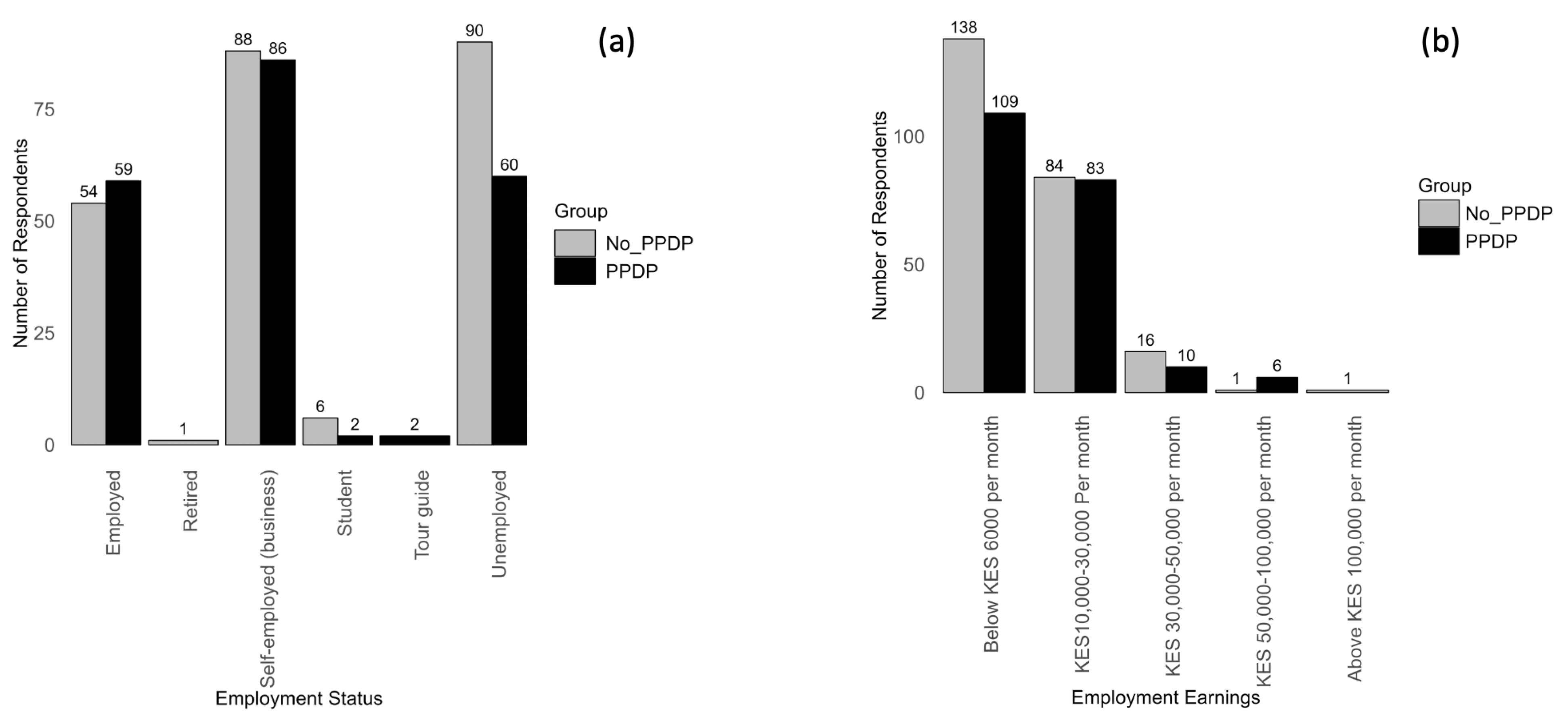

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Community Involvement in Development Activities

4.3. Factors Influencing Economic Development

4.4. Climate Change Awareness, Mitigation, and Adaptation

4.5. PPDP Critical Success Factors

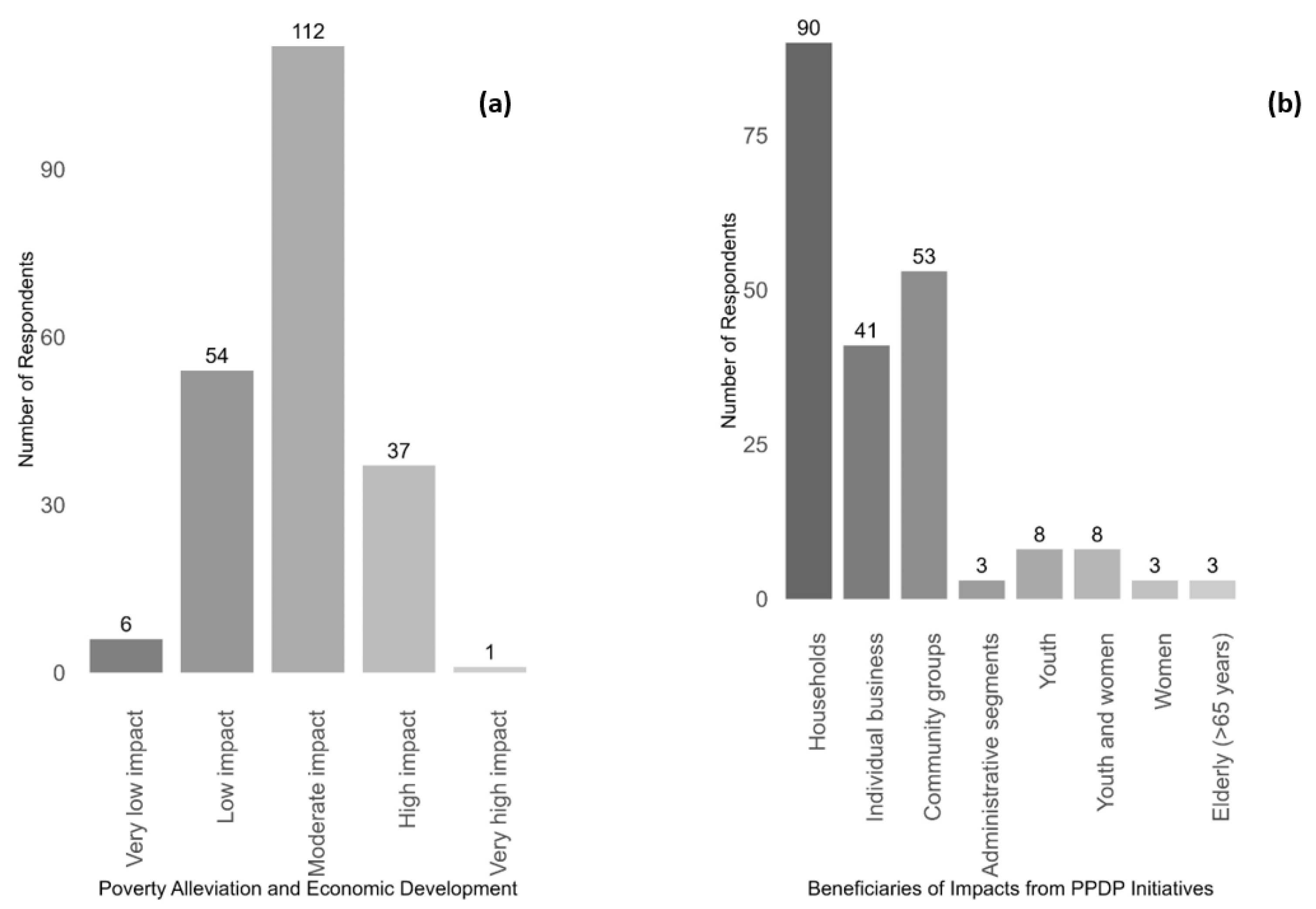

4.6. Effects of PPDP on Poverty Alleviation

4.7. Pathways to Development: Examining the Effects of the PPDP Model in Rural Kenya

4.8. Development Disparities and Solutions

5. Discussion

5.1. Access to Education and Clean Water

5.2. Social Protection and Inclusivity

5.3. Economic and Governance Empowerment

5.4. Climate Change Impacts and Resilience

5.5. Access to Healthcare

5.6. Roles Played by the Public and Private Sectors

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBO | Community-based organizations |

| CSF | Critical success factors |

| FLLOCA | Financing Locally led Climate Action |

| PPDP | Public–private development partnership |

| PPP | Public–private partnerships |

| PWDs | Person with disability |

References

- UN General Assembly. Declaration on the Right to Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, P.; Blanco, A.M. A human rights-based approach to loss and damage under the climate change regime. In The Third Pillar of International Climate Change Policy, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, A.; Morse, S.; Murphy, R.; Lynch, J.; Woolliams, E.; Fonweban, J. Translation of Earth observation data into sustainable development indicators: An analytical framework. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G.; Greve, C. Contemporary public–private partnership: Towards a global research agenda. Financ. Account. Manag. 2018, 34, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, M.; Roffe, P.; Abdel-Latif, A. Charting the Triple Interface of Public-Private Partnerships, Global Knowledge Governance, and Sustainable Development Goals. In The Cambridge Handbook of Public-Private Partnerships, Intellectual Property Governance, and Sustainable Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3023598 (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Casady, C.B.; Eriksson, K.; Levitt, R.E.; Scott, W.R. Public Management Review (Re)defining public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the new public governance (NPG) paradigm: An institutional maturity perspective. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, A. Public-Private Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Exploring Their Design and Its Impact on Effectiveness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, B.; Abbott, K.W.; Black, J.; Meidinger, E.; Wood, S. Transnational business governance interactions: Conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P.; Walker, N.F.; Wunder, S.; Rueda, X.; Blackman, A.; Börner, J.; Cerutti, P.O.; Dietsch, T.; Jungmann, L.; et al. Effectiveness and synergies of policy instruments for land use governance in tropical regions. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Thorlakson, T. Sustainability Standards: Interactions Between Private Actors, Civil Society, and Governments. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, J.; Klijn, E.H. Trust in complex decision-making networks: A theoretical and empirical exploration. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebilcock, M.; Rosenstock, M. Infrastructure Public–Private Partnerships in the Developing World: Lessons from Recent Experience. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D.A. A Research Protocol to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Public-Private Partnerships as a Means to Improve Health and Welfare Systems Worldwide. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexell, M. Global governance, gains and gender: Un-business partnerships for women’s empowerment. Int. Fem. J. Polit. 2012, 14, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, D.J.; Hartwich, F.; Grebmer, K. Public-private partnerships and developing-country agriculture: Evidence from the international agricultural research system. Public Adm. Dev. 2010, 30, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. Panacea or paradox? Cross-sector partnerships, climate change, and development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2010, 1, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W.; Brinkerhoff, J.M. Public-private partnerships: Perspectives on purposes, publicness, and good governance. Public Adm. Dev. 2011, 31, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihe, G. Ordering disorder—On the perplexities of the partnership literature: RESEARCH and EVALUATION. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2008, 67, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Environment Management Authority. Kenya- Second National Communication to the United National Framework Convention on Climate Change, Executive Summary. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Kenya%20SNC_Executive%20Summary.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- The World Bank Group. Climate Risk Profile: Kenya. 2021. Available online: www.worldbank.org (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Baithili, M.K.; Mburugu, K.N.; Njeru, D.M. Political Environment and Implementation of Public Private Partnership Infrastructure Development in Kenya. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2019, 15, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2015 GoK. Public Private Partnership Act, 2013. 2013. Available online: www.kenyalaw.org (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Chileshe, N.; Njau, C.W.; Kibichii, B.K.; Macharia, L.N.; Kavishe, N. Critical success factors for Public-Private Partnership (PPP) infrastructure and housing projects in Kenya. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 22, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank PPI Database. Private Participation in Infrastructure Database. Available online: https://ppi.worldbank.org/en/snapshots/country/kenya (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- World Bank. Tanzania Economic Update the Road Less Traveled Unleashing Public Private Partnerships in Tanzania, Africa Region Macroeconomics and Fiscal Management Global Practice; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ForumCiv. Public Policy Formulation & Oversight A Capacity Needs Assessment & Development Report; ForumCiv: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thuo, L.; Kioko, C. Marginalisation in Kenya in historical perspective (1963–2021): The starts, false starts and the last promise. In Devolution and The Promise of Democracy and Inclusion: An Evaluation of the First Decade of County Governments, 2013–2022; Kabarak University Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gready, P.; Ensor, J. Reinventing Development?: Translating Rights-Based Approaches from Theory Into Practice; Zed Books: London, UK, 2005; Available online: https://books.google.co.ke/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2ysIu55T3NcC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Gready,+P.,+%26+Ensor,+J.+(Eds.).+(2005).+Reinventing+development%3F+Translating+rights-based+approaches+from+theory+into+practice.+In+Zed+Books.&ots=u7FZmF84Qn&sig=be2eXH8Qdnw8j8vgJ908ScPoVYc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Gready%2C%20P.%2C%20%26%20Ensor%2C%20J.%20(Eds.).%20(2005).%20Reinventing%20development%3F%20Translating%20rights-based%20approaches%20from%20theory%20into%20practice.%20In%20Zed%20Books.&f=false (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Piron, L.H. Rights-based Approaches and Bilateral Aid Agencies: More Than a Metaphor? IDS Bull. 2005, 36, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Wheeler, J. Rights, Resources and the Politics of Accountability; Zed Books: London, UK, 2006; Volume 3, Available online: https://books.google.co.ke/books?hl=en&lr=&id=gmQxE1xZbzIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Newell,+P.,+%26+Wheeler,+J.+(Eds.).+(2006).+Rights,+resources+and+the+politics+of+accountability+(Vol.+3).+In+Zed+Books:+Vol.+Vol.3.&ots=pe-584j2vd&sig=Rbn1oD5-ENmgFoHKzZpUer3C9RI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Newell%2C%20P.%2C%20%26%20Wheeler%2C%20J.%20(Eds.).%20(2006).%20Rights%2C%20resources%20and%20the%20politics%20of%20accountability%20(Vol.%203).%20In%20Zed%20Books%3A%20Vol.%20Vol.3.&f=false (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Pesambili, J.C. Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation on Girls’ Schooling in Tarime, Tanzania: Voices of the Uncircumcised Girls on the Experiences, Problems and Coping Strategies. J. Educ. Pract. 2013, 4, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Freeks, F.E. The Role of the Father as Mentor in the Transmission of Values: A pastoral–Theological Study. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Asaba, R.B.; Fagan, G.H.; Kabonesa, C.; Mugumya, F. Beyond Distance and Time: Gender and the Burden of Water Collection in Rural Uganda. WH2O J. Gend. Water 2013, 2, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Do, D.N.M.; Hoang, L.K.; Le, C.M.; Tran, T. A Human Rights-Based Approach in Implementing Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) for Ethnic Minorities in Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Haq, S.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Jabeen, A. Impacts of Rural Women’s Traditional Economic Activities on Household Economy: Changing Economic Contributions through Empowered Women in Rural Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, G.T. An insect Under the Elephant: Maasai Perception of Education in Relation to Their Culture; Høgskulen på Vestlandet: Bergen, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, S.; Ramsarup, P.; Zeelen, J.; Wedekind, V.; Allais, S.; Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Monk, D.; Openjuru, G.; Russon, J.-A. Vocational education and training for African development: A literature review. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2020, 72, 465–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansz, S. A Study into Rural Water Supply Sustainability in Niassa Province, Mozambique; WaterAid: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Arce, K.; Vanclay, F. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 74, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achieno, G.O.; Mwangangi, P. Determinants of sustainability of rural community based water projects in Narok County, Kenya. Int. J. Entrep. Proj. Manag. 2018, 3, 41–57. Available online: www.iprjb.org (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Habtamu, A. Factors Affecting the Sustainability of Rural Water Supply Systems. The Case of Mecha Woreda Amhara Region, Ethiopia; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ochelle, G.O. Factors Influencing Sustainability of Community Water Projects in Kenya: A Case of Water Projects in Mulala Division, Makueni County. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agade, K.M.; Anderson, D.; Lugusa, K.; Owino, E.A. Water Governance, Institutions and Conflicts in the Maasai Rangelands. J. Environ. Dev. 2022, 31, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbottom, A.; Koomen, J.; Burford, G. Female Genital Cutting: Cultural Rights and Rites of Defiance in Northern Tanzania. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2009, 52, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Esho, T. An Exploration of the Psycho-Sexual Experiences of Women Who Have Undergone Female Genital Cutting: A Case of the Maasai in Kenya. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn 2012, 4, 132. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3987496/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Van Bavel, H.; Coene, G.; Leye, E. Changing practices and shifting meanings of female genital cutting among the Maasai of Arusha and Manyara regions of Tanzania. Cult. Health Sex. 2017, 19, 1344–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, T.K.; Strid, S. Minority migrant men’s attitudes toward female genital mutilation: Developing strategies to engage men. Health Care Women Int. 2020, 41, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, N.; Turkmani, S.; Black, K.; Hall, J.; Dawson, A. The role of men in abandonment of female genital mutilation: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Bavel, H. Is Anti-FGM Legislation Cultural Imperialism? Interrogating Kenya’s Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2022, 32, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, H. At the intersection of place, gender, and ethnicity: Changes in female circumcision among Kenyan Maasai. Gend. Place Cult. 2020, 27, 1071–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koissaba, B.R.O. Geothermal Energy and Indigenous Communities: The Olkaria Projects in Kenya, Nairobi. 2017. Available online: https://eu.boell.org/sites/default/files/geothermal-energy-and-indigenous-communities-olkariaproject-kenya.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Meyer, C.; Naicker, K. Collective intellectual property of Indigenous peoples and local communities: Exploring power asymmetries in the rooibos geographical indication and industry-wide benefit-sharing agreement. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geza, W.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Mudhara, M.; Slotow, R.; Mabhaudhi, T. ‘Is there value for us in agriculture?’ A case study of youth participation in agricultural value chains in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2280365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Kenya. The Energy Act. 2019. Available online: https://kenyalaw.org/kl/fileadmin/pdfdownloads/Acts/2019/EnergyAct__No.1of2019.PDF (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Siegrist, F. Supporting Women Entrepreneurs in Developing Countries: What Works? A Review of the Evidence Base & We-fi’s Theory of Change. 2022. Available online: www.we-fi.org (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Abegunde, A.A. Local communities’ belief in climate change in a rural region of Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 1489–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| County | FGD Level | Total Participants | Male | Female | Participant Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narok | Community | 21 | 11 | 10 | Youth reps (11), PWD (1), village elders, community health providers |

| Policy | 12 | 6 | 6 | County officials (7), CBOs/schools (2), CSOs/NGOs (2), PWD (3) | |

| Nakuru | Community | 16 | 11 | 5 | Youth reps (5), PWD (1), village elders (10) |

| Policy | 8 | 4 | 4 | County officials (5), CSOs/NGOs (2), PWD (1) |

| Economic Development Parameters | Level of Significance (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|

| Access to essential infrastructure (e.g., roads, electricity) | 0.000 *** |

| Availability of public services (e.g., healthcare, education) | 0.000 *** |

| Inclusivity and equal opportunities | 0.000 *** |

| Gender equality and women’s empowerment | 0.000 *** |

| Food Access (e.g., affordability and distribution) | 0.000 *** |

| Quality Education (e.g., access to quality schools) | 0.000 *** |

| Food Availability (e.g., supply and variety) | 0.000 *** |

| Environmental sustainability and climate change resilience | 0.02 ** |

| Business growth and entrepreneurship | 0.03 ** |

| Income levels and economic well-being | 0.05 * |

| Employment opportunities | 0.298 |

| Participation in Governance and Decision-Making | 0.484 |

| Food Quality (e.g., nutritional value, safety) | 0.655 |

| Critical Success Factors | Level of Significance (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|

| Innovation and technological advancements | 0.000 *** |

| Public–private partnerships | 0.000 *** |

| Education and skill development programs | 0.000 *** |

| Infrastructure development | 0.000 *** |

| Community engagement and social initiatives | 0.000 *** |

| Skilled workforce availability | 0.001 *** |

| Access to markets and customers | 0.002 ** |

| Business-friendly regulatory environment | 0.03 ** |

| Government policies and support | 0.032 ** |

| Development Parameter | Community Disparities and Solutions | Policy Makers Solutions | Scalable Initiatives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | Far schools (outside 20 km radius). Maasai culture placed a low value on formal education. Nomadic life disrupts school attendance, poverty, low motivation due to high unemployment, high dropout rate due to early pregnancies, peer pressure, early/forced marriages. Lack of awareness of benefits of formal education. | Addressing water access as an interlinked factor to formal education. Address early and forced marriages, and FGM. Build secondary schools and vocational training centers. Employ teachers for ECD and primary schools. | Build and upgrade schools closer to the community. Enhance water infrastructure in schools and communities. Civic education and awareness. Address harmful cultural Practices, e.g., FGM. Use role models for mentorship Programs. Recruitment teachers for ECD and primary schools. | |

| Low uptake of formal education | ||||

| Households’ Economic characteristics | Low-income jobs, one-income households, less empowered women, limited market for products, high unemployment, poverty, climate change impacts. Livestock diseases, limited knowledge on saving. | Synergize activities of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to the needs of community. Support new business ideas and entrepreneurship. Promote micro-financing and entrepreneurship. | Promote entrepreneurship. Micro-financing and access to credit. Expand market opportunities. Train in financial management and business skills. Support business ecosystem. | |

| Development | Expand market for beadwork. Secure Rapland market with fence and electricity. Promote small-scale vegetable farming and beekeeping. Training online business skills. Enhance Internet and telecommunication networks. Create friendly business regulatory environment. Remove land rates at the settlements in Rapland. Training business development and legal requirements. Set public abattoir in Suswa. | Cooperatives and trade societies. Study the uptake of Youth and Social Enterprise Fund in Olkaria. Export market for beadwork. Engage PWDs on diverse opportunities. Develop a Shanga initiative through Shanga production centers. Value addition centers for milk and potatoes in Narok. Livestock quality control lab, livestock extension services, and livestock cooperatives. | Expand local and international markets for beadwork. Promote sustainable farming for vegetables and beekeeping. Set livestock quality control lab, public abattoir, and value addition centers for potatoes and milk. Technology training for online business. Knowledge of legal requirements for business setup. Cooperatives that empower development. | |

| Business opportunities | ||||

| Promoting rights to education | Use role models for awareness. Enhance sponsorships, scholarships, and bursaries. Improve quality of educational facilities. Build secondary schools. Provide food in school, return adult education, basic computer training, digital learning, digital skills on phones, and financial and accounting literacy. Promote education for women. | PPDP to scale education programs. Scale CSR Projects on education. Civic education. Establish Vocational Training Centers (VTCs). Ensure community voices in county-integrated development plans (CIDPs) and budgeting. Affirmative action to scale education programs for women. | Build schools within the community. Implement school feeding program. Establish VTCs. Adult education. PPPs to build schools. Sponsorships, scholarships, and bursaries). Community voices in CIDPs and budgets. | |

| Promoting green jobs and green enterprises | Biogas plant and recycling centers. Support the use of Sulphur (a by-product) from geothermal to manufacture hair products. Beekeeping, water harvesting ventures, afforestation programs, smart farming, chicken keeping. Technical training on green skills, financial literacy, and business development, linkages with financial institutions. | Sensitization on green jobs and access to green funds, e.g., FLLOCA fund for green enterprises. Fund circular economy projects. Tools to Work Program (TWP) for youth. Sensitization of community on green jobs. Build capacity on carbon markets and negotiation skills. | Biogas and plastic recycling center: Local manufacturing. Tree Nurseries as a business. Technical training on green skills. Financial and business development literacy. Sensitization on green jobs. Funding policy for green jobs. Build capacity on carbon markets. | |

| Addressing unemployment | Start-up capital for youths and women. Transparency and equity in employment. Jobs for the community. Green jobs. Civic education on rights of the community. Promote formal education. Online businesses and jobs. Set up VTCs and more schools. | Quality assurance for start-ups and capital access. Promote green jobs. | Transparency and equity in employment. Develop a central market to support local businesses. Build more schools and VTCs. Online businesses and Jobs. Activate green jobs. Quality assurance and capital access to start-ups. | |

| Addressing inclusivity | Gender equity awareness, support women to leadership. Employment for youth, women, and PWDs. Fair education opportunities and awareness of the rights of PWDs. Affirmative action on opportunities for youth, women, and PWDs. | KPIs for county government officers on contracts on employment for women, PWDs, and youth. Access start-up capital for youth, women, and PWDs. Promote youth education and training. Ensure community voices in CIDPs and budgets. | Employment opportunities for Youth, Women, and PWDs through affirmative action. Inclusivity awareness. Education for Girls and PWDs. Vocational training. Women and PWDs in Leadership. Access to capital for youth, women, and PWDs. Accountability through KPIs for resources to youth, women, and PWDs. | |

| Social protection | Continuous dialogue on FGM at schools and communities. Legal actions against those involved in FGM. Involving cultural elders and area chiefs. Use role models to create more awareness. More research on drivers of FGM. Use local radio for awareness. Build more rescue centers | Understand the linkages between FGM giving birth and male circumcision. Co-create an alternative passage of rights for women within the community. Law courts closer to communities to handle FGM. Engage cultural leaders. Synergize the work of UNESCO with other NGOs. | Sustained community dialogues. Enforce legal actions. Train local law enforcers on FGM issues for effective enforcement. Involve cultural Leaders. More research on FGM. Synergize the work of UNESCO and NGOs. Advocacy. | |

| Climate change awareness, adaptation and resilience | Train community representatives on climate change adaptation and mitigation. Advocate for local radio programs on climate change. More climate change CBOs. Deal with charcoal burning. Set up tree nurseries and afforestation programs. Promote water management technologies. | Active National Climate Fund at county level. Technology to enhance resilience and access to clean water. Establish early warning systems and safe grounds. Cooperatives to support adaptation activities. | Build capacity of community for climate change adaptation and mitigation. Activation of Climate Funds at county level. Partnerships for water infrastructure. Early warning systems and safe grounds. Local radio programs on climate change. | |

| Enablers to rights-based services (quality education, health and clean water) | Employ more medical personnel and teachers. Build more primary and secondary schools. Enhanced telecommunication infrastructure. Promote water harvesting technologies. Promote adult education. Civic education on how to demand for rights from the duty bearers. Empower communities on water infrastructure management. Build and equip dispensaries. Hold government accountability on rights-based needs. | Promote public participation. Community training on participation in public issues and governance. More government involvement in rights-based needs. Optimize dispensaries. Data used to support interventions. Staffing and housing in health facilities. | Employ more medical personnel and equip health facilities. Optimize dispensaries. Employ more teachers. Promote water harvesting, storage, and conservation technologies. Empower communities for ownership and maintain water infrastructure. Improve telecommunication network. Civic education on rights-based needs as rights of the community. Training on public participation, adult education, Government accountability. Data support interventions. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiawo, D.O.; Ngila, P.M.; Mugo, J.W.; Wachira, M.M.; Njuki, L.M.; Muniu, V.; Anyura, V.; Kuria, T.; Obare, J.; Koini, M. Human Rights-Based Approach to Community Development: Insights from a Public–Private Development Model in Kenya. World 2025, 6, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030104

Chiawo DO, Ngila PM, Mugo JW, Wachira MM, Njuki LM, Muniu V, Anyura V, Kuria T, Obare J, Koini M. Human Rights-Based Approach to Community Development: Insights from a Public–Private Development Model in Kenya. World. 2025; 6(3):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030104

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiawo, David Odhiambo, Peggy Mutheu Ngila, Jane Wangui Mugo, Mumbi Maria Wachira, Linet Mukami Njuki, Veronica Muniu, Victor Anyura, Titus Kuria, Jackson Obare, and Mercy Koini. 2025. "Human Rights-Based Approach to Community Development: Insights from a Public–Private Development Model in Kenya" World 6, no. 3: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030104

APA StyleChiawo, D. O., Ngila, P. M., Mugo, J. W., Wachira, M. M., Njuki, L. M., Muniu, V., Anyura, V., Kuria, T., Obare, J., & Koini, M. (2025). Human Rights-Based Approach to Community Development: Insights from a Public–Private Development Model in Kenya. World, 6(3), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030104