Job Satisfaction and Well-Being of Care Aides in Long-Term Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

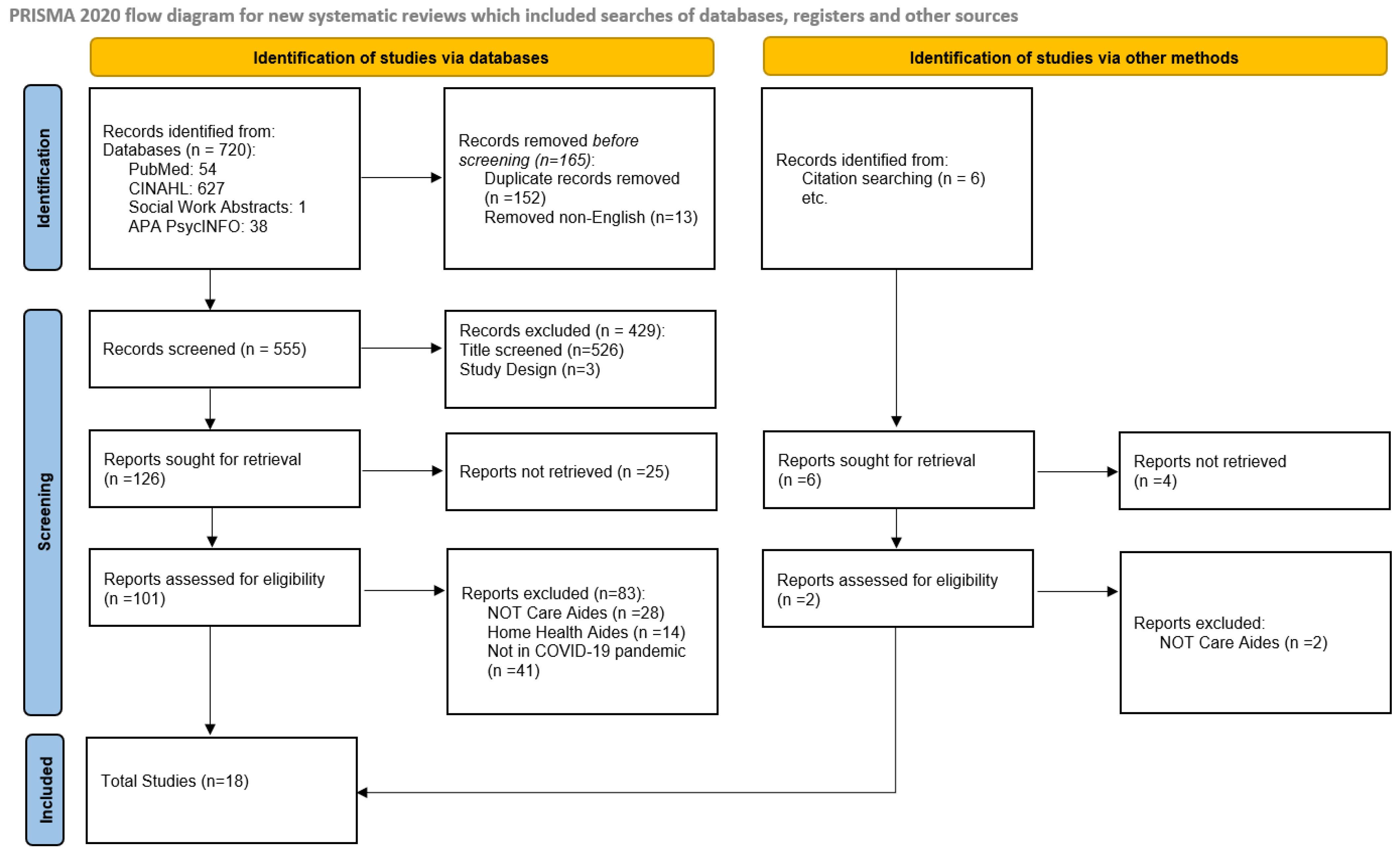

2. Methodology

2.1. Scoping Review Approach

2.2. Methodological Steps

3. Findings

3.1. Job Satisfaction

3.2. Exhaustion

3.3. Fears

3.4. Anxiety

3.5. Quality of Work Life

3.6. Workload

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact on Care Aides

4.2. Gendered Impacts

4.3. Intersectionality: Gender, Age, Education, and Migrant Status

4.4. Material Conditions: Low Income and Job Insecurity

4.5. Patient Care Implications

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Theme (Publication References) | Definition | Implication (During COVID-19 Pandemic) | |

| Detrimental Effects on Care Aides | Organizational Response | ||

| Burnout [7,9,10,20,22,27,28,29,30] | Burnout includes bodily responses to ongoing work-related stress, such as emotional and mental tiredness, a strong sense of detachment from their duties, and a reduction in self-confidence in their accomplishments or professional skills. | Personal:

|

|

| Job satisfaction [7,10,12,21,31] | Extends beyond simple emotional well-being to include positive attitudes, feelings, and perspectives on their job responsibilities and workplace. | Personal:

|

|

| Exhaustion [7,10,21,26,27,31,32] | Caregivers’ fatigue revealed a multifaceted interaction between physical, psychological, and emotional exhaustion, often leading to long term health effects such as chronic fatigue and respiratory problems. | Personal:

|

|

| Fear [7,10,11,22,27,29,31] | Fear in the context of healthcare work, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, refers to the emotional response to perceived threats, such as the risk of contracting and spreading the virus. This fear can be compounded by the uncertainty of the situation, the high mortality rate associated with the virus, and the potential consequences for both personal and family health. Fear can be heightened by inadequate protective measures, unclear communication, and the visible suffering or death of patients under a caregiver’s care. | Personal:

|

|

| Anxiety [7,9,10,11,22,27,31] | Anxiety is a pervasive feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease, typically about an imminent event or something with an uncertain outcome. In healthcare settings, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety among care aides can arise from multiple factors, including fear of infection, the pressure of increased responsibilities, unclear or constantly changing protocols, and concerns about the safety and well-being of their patients and themselves. Anxiety is more chronic and persistent than fear and can impact mental health and job performance. | Personal:

|

|

| Quality of work life [7,10,12,20,21,22,23,26] | Quality of work life refers to the overall well-being and job satisfaction of employees in relation to their work environment and job demands. It encompasses various aspects, including the balance between work and personal life, the level of stress and burnout experienced, the adequacy of resources and support, and the overall work environment. For care aides, a high quality of work life means having a supportive workplace, manageable workloads, opportunities for professional growth, and the ability to maintain a healthy balance between their job and personal life. | Personal:

|

|

| Workload [7,10,11,12,21,22,23,27,29,32] | Workload refers to the amount of work assigned to or expected from an employee within a certain period. In the context of healthcare, workload for care aides includes not only the number of patients they care for but also the complexity of the tasks they must perform, such as managing patient needs, administering care, and adhering to infection control protocols. During the COVID-19 pandemic, workloads often increased due to staffing shortages, higher patient acuity, and the need for additional safety measures, leading to increased physical and emotional strain. | Personal:

|

|

References

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19; World Health Organization [WHO]: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Beeching, J.; Fletcher, T.; Fowler, R. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment| BMJ Best Practice US. 2021. Available online: http://hpruezi.nihr.ac.uk/publications/2020/bmj-best-practice-coronavirus-disease-covid-19/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology Update. March 2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Demographic Estimates by Age and Sex, Provinces and Territories: Interactive Dashboard. 2020, September 29. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-607-x/71-607-x2020018-eng.htm (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Jones, K.; Schnitzler, K.; Borgstrom, E. The implications of COVID-19 on health and social care personnel in long-term care facilities for older people: An international scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boscart, V.; Crutchlow, L.E.; Taucar, L.S.; Johnson, K.; Heyer, M.; Davey, M.; Costa, A.P.; Heckman, G. Chronic disease management models in nursing homes: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, N.S.; Cimarolli, V.R.; Falzarano, F.; Stone, R. Organizational Factors Associated with Certified Nursing Assistants’ Job Satisfaction during COVID-19. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BC Office of the Provincial Health Officer. Residential Care COVID-19 Preventative Measure. B.C. Ministry of Health; BC Office of the Provincial Health Officer: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2021.

- White, E.M.; Wetle, T.F.; Reddy, A.; Baier, R.R. Front-line Nursing Home Staff Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J.C.; Ahmad, W.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Burgess, E.O. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Person-Centered Care Practices in Nursing Homes. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yin, P.; Xiao, L.D.; Wu, S.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; Liao, L.; Feng, H. Nursing home staff perceptions of challenges and coping strategies during COVID-19 pandemic in China. Geriatr. Nur. 2021, 42, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Prados, A.B.; Jiménez García-Tizón, S.; Meléndez, J.C. Sense of coherence and burnout in nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisio, L.D.; Varin, M.D.; Hoben, M.; Baumbusch, J.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Cummings, G.G.; Squires, J.E. To whom health care aides report: Effect on nursing home resident outcomes. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2021, 16, e12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nürnberger, L.C. Molekulare Typisierung 128 Vancomycin-Resistenter Enterococcus Faecium-Isolate von zwei Deutschen Kliniken in Essen und Nürnberg Zwischen 2011 und 2018. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM). 2023. Available online: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- EBSCO. 2023. Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- American Psychological Association. APA PsycInfo. 2023. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses [PRISMA]. 2023. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Hapsari, A.P.; Ho, J.W.; Meaney, C.; Avery, L.; Hassen, N.; Jetha, A.; Lay, A.M.; Rotondi, M.; Zuberi, D.; Pinto, A. The working conditions for personal support workers in the Greater Toronto Area during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titley, H.K.; Young, S.; Savage, A.; Thorne, T.; Spiers, J.; Estabrooks, C.A. Cracks in the foundation: The experience of care aides in long-term care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voth, J.; Jaber, L.; MacDougall, L.; Ward, L.; Cordeiro, J.; Miklas, E.P. The presence of psychological distress in healthcare workers across different care settings in Windsor, Ontario, during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 960900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.; Mak, W.; Burack, O.R.; Hokenstad, A.; Wiggins, F.; Boockvar, K.S.; Reinhardt, J.P. Perspectives of certified nursing assistants and administrators on staffing the nursing home frontline during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 57, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, J.; Amutio, A.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. Stressors, Job Resources, Fear of Contagion, and Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Nursing Home Workers in Face of the COVID-19: The Case of Spain. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, J.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Amutio, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. Satisfied as professionals, but also exhausted and worried!!: The role of job demands, resources and emotional experiences of Spanish nursing home workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e148–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, M.; Louw, J.S.; Corry, M. Experiences of a Nursing Team Working in a Residential Care Facility for Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2023, 49, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestor, S.; O’ Tuathaigh, C.; O’ Brien, T. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare staff at a combined elderly care and specialist palliative care facility: A cross-sectional study. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoedl, M.; Bauer, S.; Eglseer, D. Influence of nursing staff working hours on stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. HeilberufeScience 2021, 12, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduzu, L.; Wei, L.; Cope, V. Exploring Nursing Staff’s Experiences and Perspectives of COVID-19 Lockdown in a Residential Aged Care Setting in Australia. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2023, 49, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialavori, S.; Riva, F.; Froldi, M.; Carabelli, S.; Caimi, B.; Rossi, P.; Delle Fave, A.; Calicchio, G. Psychological distress and resilience among italian healthcare workers of geriatric services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 46, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, E.; Boudoukha, A.-H.; Karaca, Y.; Lizio, A.; Luyat, M.; Gallouj, K.; El Haj, M. Fear of COVID-19, emotional exhaustion, and care quality experience in nursing home staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 102, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Gil, C.; Kim, H.; Bea, H. Person-Centered Care, Job Stress, and Quality of Life Among Long-Term Care Nursing Staff. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styra, R.; Hawryluck, L.; McGeer, A.; Dimas, M.; Lam, E.; Giacobbe, P.; Lorello, G.; Dattani, N.; Sheen, J.; Rac, V.E.; et al. Support for health care workers and psychological distress: Thinking about now and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2022, 42, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewko, S.J.; Cooper, S.L.; Huynh, H.; Spiwek, T.L.; Carleton, H.L.; Reid, S.; Cummings, G.G. Invisible no more: A scoping review of the health care aide workforce literature. BMC Nurs. 2015, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population/Problem/Patient | Intervention/Issue | Effect/Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Care aides | Working in long-term care (during COVID-19) | Job satisfaction |

| Theme | Care Aides | Long-Term Care | Job Satisfaction | COVID-19 Pandemic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsidiary Search Terms | Nursing Assistants Personal Support Workers (PSWs) Health Care Assistant | Nursing Homes Homes for the Aged Residential Home | Burnout Distress Retention Burden Quality of life Fatigue | 2019–2023 |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Care aides Long-term care COVID-19 pandemic Burnout/retention/distress/burden Job satisfaction/quality of life | Non-English Hospitals or community-based settings Non-care aide healthcare workers Not related to COVID-19 pandemic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarfjoo Kasmaei, M.; Freeman, S.; Banner, D.; Klassen-Ross, T.; Martin-Khan, M. Job Satisfaction and Well-Being of Care Aides in Long-Term Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Literature Review. World 2025, 6, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020062

Sarfjoo Kasmaei M, Freeman S, Banner D, Klassen-Ross T, Martin-Khan M. Job Satisfaction and Well-Being of Care Aides in Long-Term Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Literature Review. World. 2025; 6(2):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020062

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarfjoo Kasmaei, Maryam, Shannon Freeman, Davina Banner, Tammy Klassen-Ross, and Melinda Martin-Khan. 2025. "Job Satisfaction and Well-Being of Care Aides in Long-Term Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Literature Review" World 6, no. 2: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020062

APA StyleSarfjoo Kasmaei, M., Freeman, S., Banner, D., Klassen-Ross, T., & Martin-Khan, M. (2025). Job Satisfaction and Well-Being of Care Aides in Long-Term Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Literature Review. World, 6(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020062