Socioecological System Transformation: Lessons from COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Complex Systems, Socioecological Resilience, and the COVID-19 Shock

- Ecological limits to growth: On a finite planet, there are biophysical limits to complexity and growth. All health innovations and systems—whether investments in clean water or an HIV vaccine—come with a biophysical cost and proceed at the expense of “ecological space” elsewhere in the system [8].

- Ecological limits to societal connectivity: Tackling problems of culture, justice, health, and social change in relation to health presents new challenges. Societal connectivity both creates the conditions for cherished gains in social justice and wellbeing and at the same time exacerbates risks associated with tightly coupled socioecological systems.

- Geopolitical constraints regarding trade relations: Peak globalization and an emerging consensus that the West’s relationship with international partners has become very dependent may see a systemic shift away from outsourcing labor intensive manufacturing to East Asia and the re-emergence of more capital-intensive production within Western economies.

- Reimagining the importance of “care”: We are increasingly faced with a tradeoff between capital intensive medical technologies that depend on growth, and improvements in public health that involve the reordering of social relationships and institutions, including more localized solutions.

3. Prefigurative Politics and Resilience

4. Systemic Change and the Importance of Alternative Ontologies

5. Dominant Regimes under Question

6. Cooperation and Prosocial Behaviors

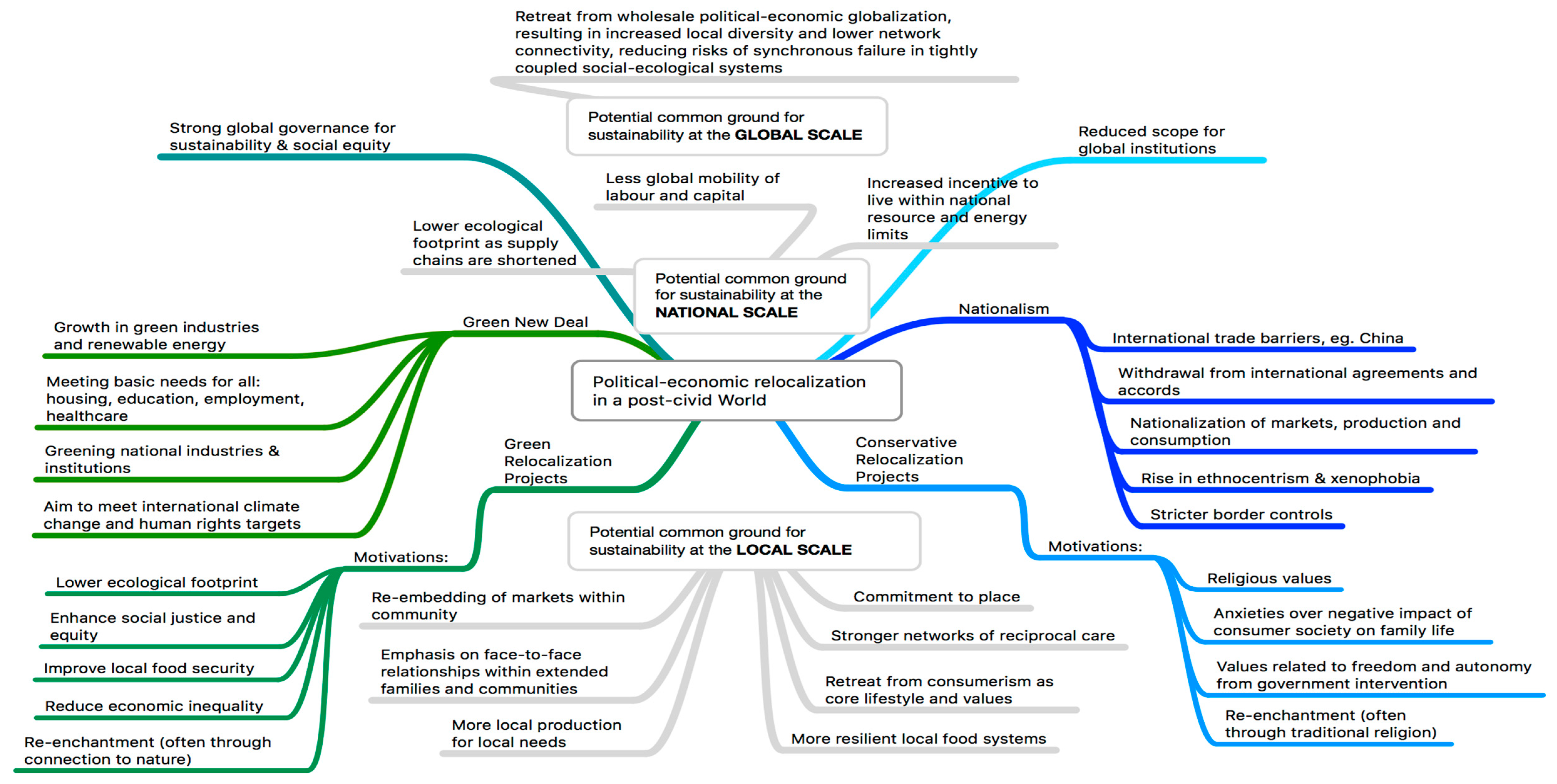

- How can right and left visions of localism be reconciled?

- What should be the appropriate balance between global economic integration and local sufficiency?

- What do more locally based, public-health-oriented, and less medicalized health systems look like?

- What are the systemic dangers of moving in this direction?

6.1. Cooperative and Prosocial Example: Makers during COVID-19

6.2. Tradeoffs and Uncertainy in Complex Systems

- Steady states are always provisional and temporary: Any ecological or socioeconomic equilibrium produced by an evolutionary, path-dependent process is likely to be dynamic and generative of endogenous processes of transformation.

- What is good for the system is not necessarily good for individuals or groups within that system: Wholesale system change involving “creative destruction” necessarily involves bad and even catastrophic outcomes for individuals. We are comfortable with this when talking about forest fires or fisheries, but less so when those involved are human.

- Alternative pathways embody very difficult tradeoffs involving cherished values and priorities: Possible or conceivable political and socioeconomic configurations exist on a “landscape” that defines the relationship between different parameters and phenomena. Any particular configuration cannot occupy different positions in such a landscape simultaneously.

- Viable alternatives may not be visible: What is perceived as “possible” or viable depends greatly on discourse (the hegemonic “common sense”) but also on the vantage point of the present state of affairs. Large areas of the landscape of the “adjacent possible” may not be visible.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.R.; Lenton, T.M.; Bascompte, J.; Brock, W.; Dakos, V.; Koppel, J.v.d.; Leemput, I.A.v.d.; Levin, S.A.; Nes, E.H.; et al. Anticipating Critical Transitions. Science 2012, 338, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet; Earthscan: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 1-84407-894-9. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, P.A. Managing without Growth Slower by Design, Not Disaster; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84844-299-3. [Google Scholar]

- Homer-Dixon, T.; Walker, B.; Biggs, R.; Crépin, A.-S.; Folke, C.; Lambin, E.; Peterson, G.; Rockström, J.; Scheffer, M.; Steffen, W.; et al. Synchronous failure: The emerging causal architecture of global crisis. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; Dias, B.F.d.S.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.; Frumkin, H. Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-61091-966-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker, S. Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, illustrated ed.; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-525-42757-5. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E.; Farley, J. Ecological Economics: Principles And Applications; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-55963-312-3. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D. Globally networked risks and how to respond. Nature 2013, 497, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.D. Sounding the Alarm: Health in the Anthropocene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leach, D.K. Prefigurative Politics. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements; Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-470-67487-1. [Google Scholar]

- Boggs, C. Radical America. Radic. Am. 1977, 11, 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Breines, W. Community and Organization: The New Left and Michels’ “Iron Law”. Soc. Probl. 1980, 27, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, F.; Haaken, J.; Moskovitz, L.; Jackson, S. Rethinking Prefigurative Politics: Introduction to the Special Thematic Section. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 2016, 4, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, W. Hegemony, Counter-hegemony, Anti-hegemony. J. Social.Stud. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kish, K. Reclaiming Freedom Through Prefigurative Politics. In Liberty and the Ecological Crisis; Routledge: Abington upon Thames, UK, 2019; pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F.; Zimmerman, B.; Patton, M. Getting to Maybe: How the World Is Changed, reprint ed.; Vintage Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; ISBN 978-0-679-31444-8. [Google Scholar]

- Beddoe, R.; Costanza, R.; Farley, J.; Garza, E.; Kent, J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Martinez, L.; McCowen, T.; Murphy, K.; Myers, N.; et al. Overcoming systemic roadblocks to sustainability: The evolutionary redesign of worldviews, institutions, and technologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2483–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friel, S. Climate change and the people’s health: The need to exit the consumptagenic system. Lancet 2020, 395, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era; D’Alisa, G.; Demaria, F.; Kallis, G. (Eds.) Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-138-00077-3. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, C. COVID-19 Crisis Is a Tipping Point. Will We Invest in Planetary Health, or Oil and Gas? Available online: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/03/24/opinion/covid-19-crisis-tipping-point-will-we-invest-planetary-health-or-oil-and-gas (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Evitaputri, D. Prime Minister Must Tackle Climate Change with Same Urgency as COVID-19: Open Letter from Health Groups. Available online: https://www.caha.org.au/openletter-pm (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Kish, K.; Quilley, S. Wicked Dilemmas of Scale and Complexity in the Politics of Degrowth. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, R. Transition Handbook: From Oil Dependency to Local Resilience; Uit Cambridge Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2014; ISBN 0-85784-215-3. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, K.A. The Homebrew Industrial Revolution: A Low-Overhead Manifesto; BookSurge: Charleston, SC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4392-6699-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M.T.; Peters, J. Localism in the Mass Age: A Front Porch Republic Manifesto; Cascade Books: Eugene, OR, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5326-1443-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J. Small Is Still Beautiful: Economics as if Families Mattered; Intercollegiate Studies Institute: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-933859-05-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S.M. Earthly Bodies, Magical Selves: Contemporary Pagans and the Search for Community; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-520-22086-7. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B. Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-520-26100-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, R. The Benedict Option; RANDOM HOUSE CANADA: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-7352-1329-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrysch, S. Imagination challenges in planetary health: Re-conceptualising the human-environment relationship. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e372–e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedentop, L. Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-7139-9644-9. [Google Scholar]

- Quilley, S. Liberty in the (Long) Anthropocene: The ‘I’ and the ‘We’ in the Longue Duree. In Liberty and the Ecological Crisis: Freedom on a Finite Planet; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman, S. At Home in the Universe; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0195111309. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, M.; Tisdell, J.; Canny, B.; Zimitat, C. Health care and the future of economic growth: Exploring alternative perspectives. Health Econ. Policy Law 2020, 15, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quilley, S.; Zywert, K. Livelihood, Market and State: What does A Political Economy Predicated on the ‘Individual-in-Group-in-PLACE’ Actually Look Like? Sustainability 2019, 11, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCartney, M. Medicine: Before COVID-19, and after. Lancet 2020, 395, 1248–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J. Clinicians are leading service reconfiguration to cope with covid-19. BMJ 2020, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Togoh, I. Spain To Roll Out Permanent Universal Basic Income ‘Soon’. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/isabeltogoh/2020/04/06/spain-to-roll-out-permanent-universal-basic-income-soon/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Hensher, M. Covid-19, unemployment, and health: Time for deeper solutions? BMJ 2020, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilley, S. Can progressives shimmy? IPPR Progr. Rev. 2020, 27, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscrop, D. Opinion | In Canada, an Inspiring Movement Emerges in Response to the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/24/canada-an-inspiring-movement-emerges-response-coronavirus/ (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- WHO Commemorating the 40th Anniversary of Smallpox Eradication. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2020/05/08/default-calendar/commemorating-the-40th-anniversary-of-smallpox-eradication (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Bachan, R. Grade inflation in UK higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1580–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Cunliffe, P. Saving Britain’s Universities. Available online: https://www.cieo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Saving-Britains-Universities-Cieo-1-1.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- The patient accumulation of successes. The Economist, 22 December 2001.

- Quilley, S. A localist model for higher education. Available online: https://sdp.org.uk/sdptalk/a-localist-model-for-higher-education/ (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Pluckrose, H.; Lindsay, J. Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms Everybody; Pitchstone Publishing: Durham, NC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-63431-202-8. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, M. The Case for Remote Work; Economics Working Paper; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Cities in a Post-COVID World. Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography (PEEG) 2041; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, M.; Overman, H. Will Coronavirus Cause a Big City Exodus? Available online: https://www.coronavirusandtheeconomy.com/question/will-coronavirus-cause-big-city-exodus (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Terry, S.; Richardson, J. COVID-19 Is Speeding up White Flight: Now Is the Time to Invest in Affordable Housing. Available online: https://www.salon.com/2020/10/30/covid-19-is-speeding-up-white-flight-now-is-the-time-to-invest-in-affordable-housing/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- McKenna, M. Flight from Democratic Stronghold Cities Accelerates. Available online: https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/jun/15/flight-from-democratic-stronghold-cities-accelerat/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Goodhart, D. The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-84904-799-9. [Google Scholar]

- Young, T. The Liberals and the Deplorables. Available online: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-liberals-and-the-deplorables (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. The evolution of strong reciprocity: Cooperation in heterogeneous populations. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2004, 65, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilley, S. Between MAGA and E.F. Schumacher: A Post-Pandemic Political Economy. Available online: https://www.british-intelligence.co.uk/british-intelligence-articles/LONG-READ--BETWEEN-MAGA-AND-E.F.-SCHUMACHER-%3A-A-POST-PANDEMIC-POLITICAL-ECONOMY (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Quilley, S. Green Politics and the Right: Possible Alliance? In Proceedings of the 12th Biennial Conference of the Canadian Society for Ecological Economics, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 22–25 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Törnberg, A. Combining transition studies and social movement theory: Towards a new research agenda. Theory Soc. 2018, 47, 381–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Applying Resilience Thinking. Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2015-02-19-applying-resilience-thinking.html (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Oladapo, B.I.; Ismail, S.O.; Afolalu, T.D.; Olawade, D.B.; Zahedi, M. Review on 3D printing: Fight against COVID-19. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 258, 123943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y.Y.C.; Tan, H.W.; Patel, D.C.; Choong, W.T.N.; Chen, C.-H.; Low, H.Y.; Tan, M.J.; Patel, C.D.; Chua, C.K. The global rise of 3D printing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Noguerol, T.; Paulano-Godino, F.; Menias, C.O.; Luna, A. Lessons learned from COVID-19 and 3D printing. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruskin, J. On the Nature of Gothic Architecture: And Herein of the True Functions of the Workman in Art ...; Smith, Elder, Company: London, UK, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, W. Hopes and Fears for Art; Ellis and White: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 9798572733549. [Google Scholar]

- Frauenfelder, M. Make: Technology on Your Time Volume 25; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Newton, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4493-9398-4. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, P. Creating Is Not Just a “Nice” Activity; It Transforms, Connects and Empowers. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/culture-professionals-network/2016/mar/17/making-activity-transforms-connects-empowers (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Riley, J.; Corkhill, B.; Morris, C. The Benefits of Knitting for Personal and Social Wellbeing in Adulthood: Findings from an International Survey. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 76, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöllänen, S.; Voutilainen, L. Crafting Well-Being: Meanings and Intentions of Stay-at-Home Mothers’ Craft-Based Leisure Activity. Leis. Sci. 2018, 40, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-06-187672-1. [Google Scholar]

- Geda, Y.E.; Topazian, H.M.; Roberts, L.A.; Lewis, R.A.; Roberts, R.O.; Knopman, D.S.; Pankratz, V.S.; Christianson, T.J.H.; Boeve, B.F.; Tangalos, E.G.; et al. Engaging in cognitive activities, aging, and mild cognitive impairment: A population-based study. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterton, P.; Pusey, A. Beyond capitalist enclosure, commodification and alienation. Postcapitalist praxis as commons, social production and useful doing. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvarousis, A.; Kallis, G. Commoning Against the Crisis; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens, M. The Political Economy of Peer Production. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237720052_The_Political_Economy_of_Peer_Production (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Zywert, K.; Quilley, S. Health systems in an era of biophysical limits: The wicked dilemmas of modernity. Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People, Land, and Community: Collected E. F. Schumacher Society Lectures; Hannum, H. (Ed.) Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-300-06966-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Beck-Gernsheim, E. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7619-6112-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity: Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7456-2410-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tainter, J.A. The Collapse of Complex Societies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-521-34092-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovelock, J. A Rough Ride To the Future; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-241-00476-0. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K. The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto, 1st ed.; Prometheus Books: Amherst, NY, USA, 1844; ISBN 978-0-87975-446-4. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1942; ISBN 978-0-415-10762-4. [Google Scholar]

- Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems, 2nd ed.; Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. (Eds.) Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-55963-857-9. [Google Scholar]

- Houle, P.; Turcotte, M.; Wendt, M. Changes in Parents’ Participation in Domestic Tasks and Care for Children from 1986 to 2015; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017; ISBN 978-0-660-06840-4. [Google Scholar]

- Guterres, A. Put Women and Girls at the Centre of Efforts to Recover from COVID-19. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/un-coronavirus-communications-team/put-women-and-girls-centre-efforts-recover-covid-19 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Myers, K.R.; Tham, W.Y.; Yin, Y.; Cohodes, N.; Thursby, J.G.; Thursby, M.C.; Schiffer, P.; Walsh, J.T.; Lakhani, K.R.; Wang, D. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kish, K.; Sanniti, S. A Crisis of Care: Who Bares the Burden of a Transition to Low-Growth Economies. Ecol. Econ. 2021. (under review). [Google Scholar]

- Horton, O. Covid-19 Will Have Lasting Negative Impact on Women, French Minister Warns. Available online: https://www.rfi.fr/en/france/20200428-covid-19-will-have-lasting-negative-impact-on-women-french-minister-warns-sexual-domestic-violence (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Regeringskansliet Measures to Address Increased Vulnerability Due to the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.government.se/articles/2020/05/measures-to-address-increased-vulnerability-due-to-the-coronavirus/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kish, K.; Zywert, K.; Hensher, M.; Davy, B.J.; Quilley, S. Socioecological System Transformation: Lessons from COVID-19. World 2021, 2, 15-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/world2010002

Kish K, Zywert K, Hensher M, Davy BJ, Quilley S. Socioecological System Transformation: Lessons from COVID-19. World. 2021; 2(1):15-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/world2010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKish, Kaitlin, Katharine Zywert, Martin Hensher, Barbara Jane Davy, and Stephen Quilley. 2021. "Socioecological System Transformation: Lessons from COVID-19" World 2, no. 1: 15-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/world2010002

APA StyleKish, K., Zywert, K., Hensher, M., Davy, B. J., & Quilley, S. (2021). Socioecological System Transformation: Lessons from COVID-19. World, 2(1), 15-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/world2010002