1. Introduction

Surgical implants are frequently used in the field of Orthopaedic Surgery. These implants are used in a wide variety of surgeries, ranging from acute trauma to joint arthroplasty. The ideal implant is one that has optimal strength, stiffness, bio-compatibility and is inexpensive to manufacture. Currently, there are various materials that implants are derived from, such as metal, polymer and ceramic, each with their own advantages and disadvantages [

1,

2,

3].

The choice of implant is often dependent on the specific pathology and implant-specific characteristics. Metallic implants have been traditionally used, with favourable stiffness and durability [

4,

5]. However, there is limited patient-centred research on patient perspectives and awareness regarding the use of metallic implants in Orthopaedic surgery. Patients may have misconceptions about the lifestyle modifications and potential side effects expected after receiving a metallic surgical implant [

6]. Cultural differences in perception such as viewing metallic implants as a foreign body or economic concerns may also shape patients’ concerns.

This study aims to investigate patients’ self-perceived awareness, knowledge and concerns toward metallic implant usage in Orthopaedic surgery, in order to provide a tailored and efficient means of pre-operative counselling.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) of the National Healthcare Group (NHG), Singapore. A single-centred, cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was performed in a single tertiary centre in Singapore. The piloted questionnaire was anonymous and voluntary. It was initially piloted on 5 patients prior to deployment to assess readability and understanding. Patients were recruited from the Orthopaedic surgery specialist outpatient clinic. Inclusion criteria included patients (a) aged 21 to 75 years, (b) on follow-up with an Orthopaedic surgeon for a clinical condition. Exclusion criteria included patients who (a) have had prior metal implants before, (b) are medical and healthcare practitioners and (c) have worked in the healthcare industry prior. Patients who had metal implants before were excluded to avoid bias from previous exposure. This study did not contain language barriers as all patients were able to read the questionnaire in English.

Demographical data such as age, race, socioeconomic background (highest education qualification, occupation and current income level) were collected. A self-designed questionnaire (

Table 1) was then administered.

This questionnaire consisted of three main parts. For the first part, on a Likert scale of 1–5 (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree), patients were asked to grade their self-perceived knowledge on metallic implants.

The second part included 6 questions designed to determine the level of knowledge of patients on metallic implants and their views on the complications of having metal implants in their bodies.

Finally, for the last part, patients were asked to grade how comfortable they were with having metal implants in their body and if their preference would change if there was a non-metallic surgical option available. A list of common considerations regarding metallic implants was provided to participants. Participants were asked to rate their concerns for each factor via a Likert scale from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). We defined significant patient concern as ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly Agree’. In addition, patients were asked to express their comfort levels and willingness to have metallic implants, as compared to a non-metallic equivalent implant. The full questionnaire is available as

Supplementary Material.

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with frequencies and percentages for discrete data. Continuous data was analysed with means and standard deviation or median with inter-quartile ranges. Categorical data was analysed using the chi-square test where appropriate. A two-tailed significance level of 0.05 was used for all the tests. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 13 (StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

A total of 100 patients were recruited. There were 56 males (56%) and 44 females (44%). Ages of the patients were collected in brackets as shown in

Table 2. Patients were stratified into younger patients (<50 years) and older patients (≥50 years); there were 51 younger patients (51%) and 49 older patients (49%), respectively. The majority of the patients were Chinese (59%), and 32% achieved tertiary education qualifications.

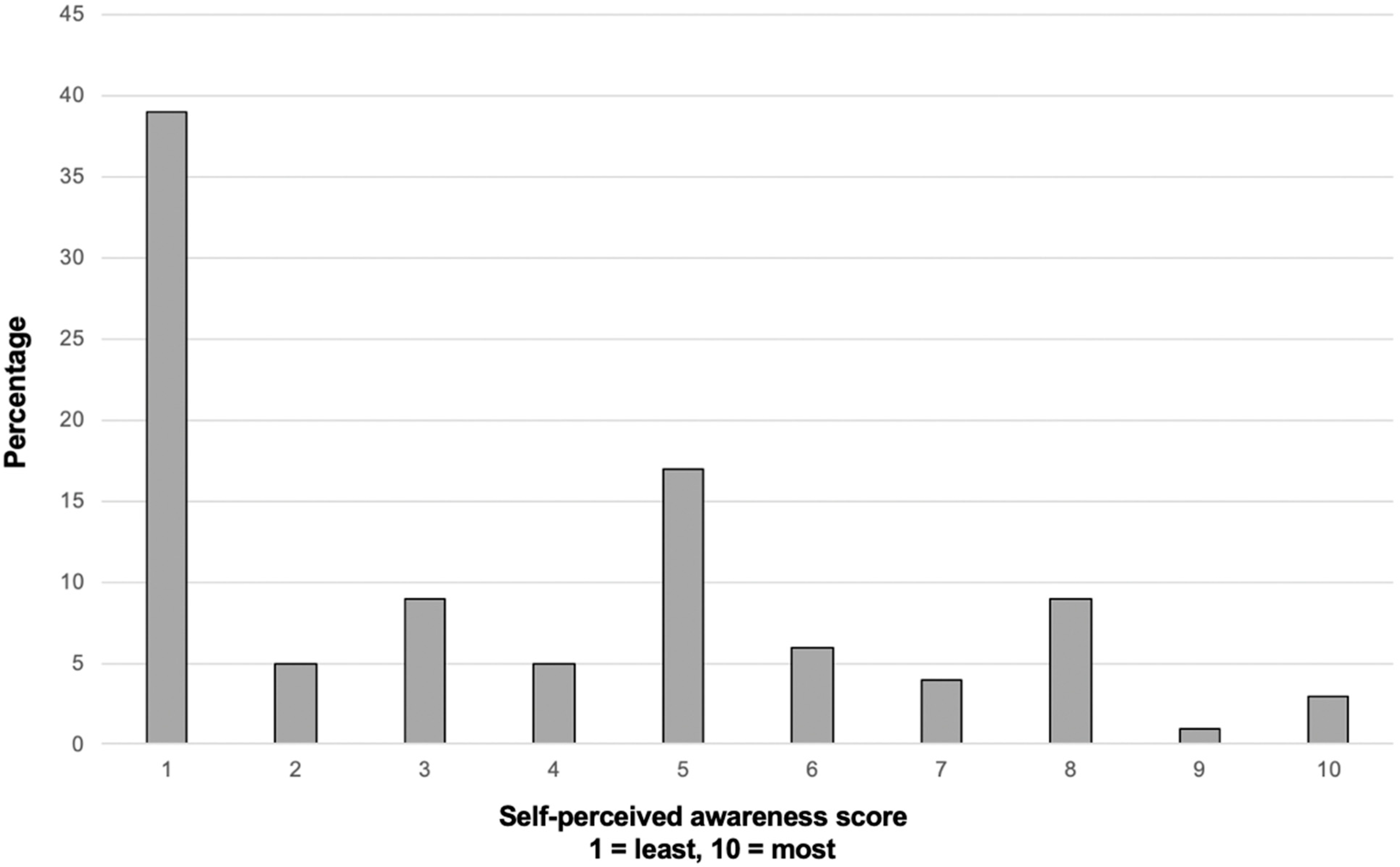

Patients were asked to rate their self-perceived awareness about metallic surgical implants on a Likert scale of 1 (Fully Unaware) to 10 (Fully Aware) (

Figure 1). The median score of self-perceived awareness was 3 (IQR 1, 5). Significantly, 40% reported a score of 1, highlighting a severe lack of awareness regarding metal implants. Patients who had family members who underwent a surgery with metallic implants had a significantly higher self-perceived awareness mean score of 4.5 (SD 2.8), compared to 3.3 (SD 2.6) (

p < 0.05).

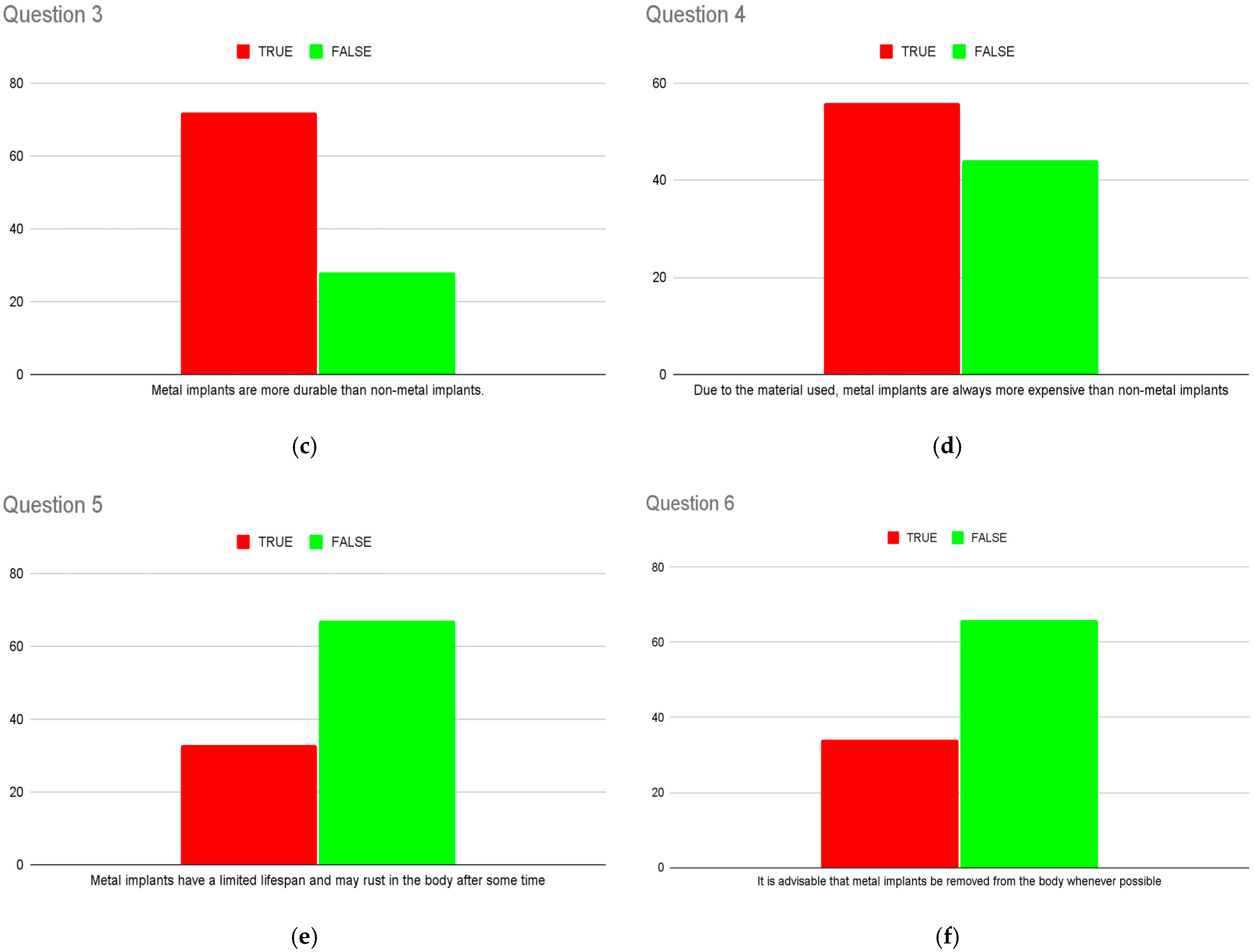

Patients’ knowledge of metallic implant properties was assessed via six questions (

Figure 2). These questions were designed to assess both basic and nuanced knowledge regarding metallic implant usage. The median percentage of correct answers across these six questions was 46% (IQR 31, 67).

Younger patients did not report a significantly different (

p = 0.68) self-perceived awareness score (3.4, SD 2.9) compared to older patients (3.7, SD 2.6). There was also no significant difference in self-perceived awareness in patients with different educational levels (

p = 0.45). With regard to the questions, there was no significant difference in percentage of accurate answers in any of the questions except for Question 5 (metal implants will rust in the body after some time). In total, 74% of younger patients answered this question correctly, compared to 50% of older patients (

p < 0.05), as seen in

Table 3. In addition, there was a significantly higher percentage of accurate answers for this question in patients who completed a tertiary education as opposed to those who did not (

p < 0.05), as seen in

Table 4.

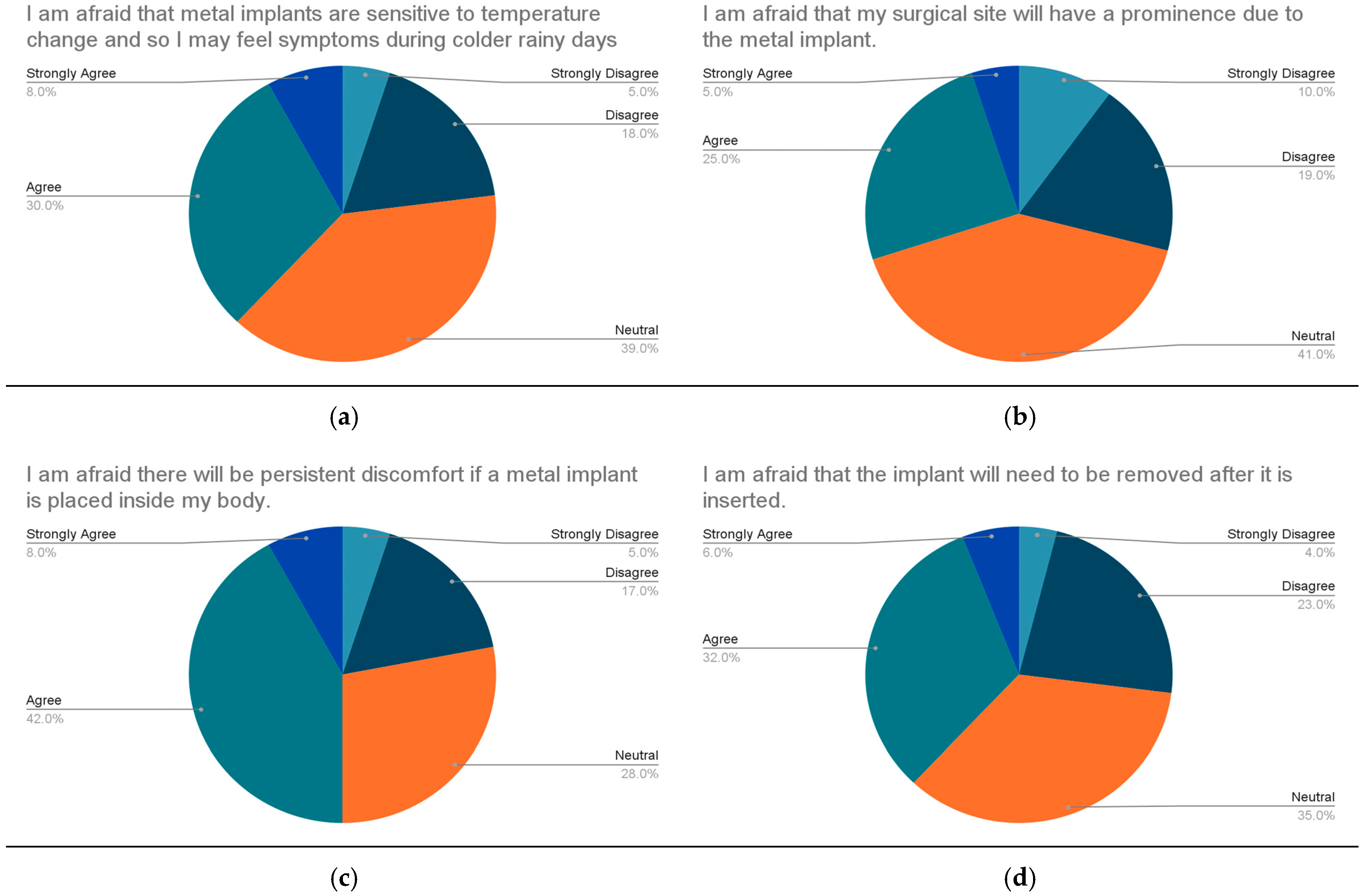

The top concerns of patients with regard to metallic implants were costs of surgery (51%), risk of rejection of implants (50%) and persistent discomfort after surgery (50%). Other concerns included inconvenience through airport security (39%), the need to remove the implant post-surgery (38%) and prominence after surgery (30%) (

Figure 3).

Patients were asked to express their comfort levels and willingness to have metallic implants, as compared to a non-metallic equivalent implant. Slightly over half of the patients (54.5%) were neutral with the usage of metallic implants in Orthopaedic surgery. Additionally, 4% and 24% were willing to use metallic implants (‘Strongly agree’ and ‘Agree’, respectively). In total, 17.2% of the patients indicated that they were unwilling to use metallic implants at all. For patients who were willing to use metallic implants, approximately half (52.1%) stated that they were indifferent to the usage of metallic implants as they were necessary to improve the quality of their lives.

4. Discussion

The use of metallic implants is common and widespread in Orthopaedic Surgery, ranging from Trauma [

7] to Arthroplasty [

8], due to their favourable stiffness and durability [

5].

Our results show that patients had low levels of self-perceived awareness and knowledge regarding metallic implants. The median score of self-perceived awareness was 3 (on a Likert scale of 1 to 10). In addition, the median percentage of correct answers testing patients’ knowledge of metallic implant properties was only 46%.

A study performed by Al-Rub et al. in 2014 showed that patients had little information regarding their hip or knee prosthesis [

6]. A total of 94% of patients did not know the model of joint replacement they had, and 85% of the patients did not know what materials the implant was made from.

Other studies have also shown that patients feel under-informed regarding implanted devices [

9] and poor patient education regarding implants [

10].

Patients’ understanding of both their Orthopaedic pathology and treatment modality is essential [

11]. Good pre-operative counselling and explanation allow them to make informed decisions, adhere to treatment and help with recovery. A paper by Koh et al. [

12] in 2010 details a clinical practice with patient involvement in graft decision making; the key factor affecting their ultimate decision was the surgeon’s explanation.

Another paper by Giannoudis et al. explored patient perspectives on the use of carbon fibre plates [

13]. Patients were provided with information regarding the current literature on carbon fibre implants and the advantages and disadvantages of carbon fibre implants and traditional metallic implants. A questionnaire was then performed assessing their understanding and willingness for a carbon fibre implant. All patients thought the information provided was adequate, with 87 out of 99 patients reporting that they would choose a carbon fibre implant. This highlights the importance of the provision of adequate pre-operative information on implant choice and its advantages and disadvantages. This may be in the form of audiovisual materials or multilingual information.

In addition, our results show that patients who had family members who underwent a surgery with metallic implants had a significantly higher self-perceived awareness mean score. This shows that the provision of information, likely through family members’ experiences, improves awareness of metallic implants. This may also imply that the low level of awareness is more reflective of exposure to the topic rather than educational understanding.

In our paper, the top concerns of patients with regard to metallic implants were noted to be the costs of surgery, risk of rejection of implants, and persistent discomfort after surgery. Other concerns included inconvenience through airport security, the need to remove implants post-surgery and prominence after surgery.

The literature does show evidence of metal hypersensitivity or allergy, especially to chromium and nickel [

14]. However, the risks to patients have been considered minimal, with these biomaterials well tolerated in bulk, as long as they are not infected and stable [

15].

A paper by Tan et al. studying the reasons for implant removal after distal radius fractures in our local Singaporean population showed that 19 out of 44 patients who had their implants removed did not have a clinical reason [

16]. There is currently no common consensus in the literature regarding the need for implant removal in patients with healed fractures [

17], unless clinically indicated. As such, routine removal of implants is not recommended, which may allay patients’ concerns about the need for repeat surgery.

The detection of metallic implants in airport metal detectors has been well documented, with both arthroplasty and trauma products detected by either an archway detector or a handheld detector in a paper by Kamineni et al. [

18]. The paper’s recommendation for the provision of a statement from the attending surgeon regarding the type and location of the implant is a simple one. Most of our local population receive an implant card or doctor’s memo detailing their type and location of implant.

Approximately 15% of the patients in our study opted for a non-metallic option where possible. Our paper highlights the need for properly tailored pre-operative counselling addressing their main concerns, with the provision of adequate information regarding metallic implants in our local population. This also helps with any potential psychological impact of implant concerns, such as any anxiety or uncertainty regarding the surgery.

After the implementation of a system of pre-operative counselling, future studies are being planned to review the changes in patients’ perspectives and understanding of metallic implants.

5. Conclusions

There is a poor level of self-reported awareness on metallic implants and a lack of knowledge regarding the use of metallic implants in Orthopaedic procedures among patients in our local population. The top concerns regarding the usage of metallic implants were cost, adverse reaction to metal and persistent discomfort. A significant percentage of patients prefer to use non-metallic implant options if available. This highlights the need for tailored pre-operative counselling for the provision of information and to address patients’ concerns regarding implant materials accurately.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.L.H.; methodology, S.W.L.H. and C.M.P.T.; formal analysis, W.Y.A. and M.D.H.S.; investigation, W.Y.A. and M.D.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Y.A. and M.D.H.S.; writing—review and editing, C.M.P.T. and S.W.L.H.; supervision, S.W.L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was granted a waiver of consent by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the National Healthcare Group (2023/00020 approved on 23 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

The waiver of consent was approved as only anonymised data was collected with no identifiable information.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prakasam, M.; Locs, J.; Salma-Ancane, K.; Loca, D.; Largeteau, A.; Berzina-Cimdina, L. Biodegradable Materials and Metallic Implants—A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2017, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocadal, O.; Ozler, T.; Bolukbasi, A.E.T.; Altintas, F. Non-traumatic Ceramic Head Fracture in Total Hip Arthroplasty with Ceramic-on-Ceramic Articulation at Postoperative 16th Years. Hip Pelvis 2019, 31, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczęsny, G.; Kopec, M.; Politis, D.J.; Kowalewski, Z.L.; Łazarski, A.; Szolc, T. A Review on Biomaterials for Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology: From Past to Present. Materials 2022, 15, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, P.; Hu, R.; Hu, Y. Bone Defects in Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty and Management. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 11, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.C. 3D-printed patient-specific applications in orthopedics. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2016, 8, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Al-Rub, Z.; Hussaini, M.; Gerrand, C.H. What do patients know about their joint replacement implants? Scott. Med. J. 2014, 59, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westrick, E.R.; Bernstein, M.; Little, M.T.; Marecek, G.S.; Scolaro, J.A. Orthopaedic Advances: Use of Three-Dimensional Metallic Implants for Reconstruction of Critical Bone Defects After Trauma. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 31, e685–e693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innocenti, M.; Vieri, B.; Melani, T.; Paoli, T.; Carulli, C. Metal hypersensitivity after knee arthroplasty: Fact or fiction? Acta Biomed. 2017, 88 (Suppl. S2), 78–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, N.A.; Reich, A.J.; Graham, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Nguyen, L.L.; Weissman, J.S. Patient perspectives on the need for implanted device information: Implications for a post-procedural communication framework. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.; Bahammam, S.; Chen, C.Y.; Hojo, Y.; Kim, D.; Kondo, H.; Da Silva, J.; Nagai, S. A cross-sectional survey of patient’s perception and knowledge of dental implants in Japan. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2022, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagley, C.; Hunter, A.; Bacarese-Hamilton, I. Patients’ misunderstanding of common orthopaedic terminology: The need for clarity. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2011, 93, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koh, H.S.; In, Y.; Kong, C.G.; Won, H.-Y.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Factors affecting patients’ graft choice in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2010, 2, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoudis, V.P.; Rodham, P.; Antypas, A.; Mofori, N.; Chloros, G.; Giannoudis, P.V. Patient perspective on the use of carbon fibre plates for extremity fracture fixation. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2023, 33, 2573–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, S.F.; Helm, M.M.; Meath, B.; Adams, C.; Packianathan, N.; Uhl, R. Exploring the Incidence, Implications, and Relevance of Metal Allergy to Orthopaedic Surgeons. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2019, 3, e023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibon, E.; Amanatullah, D.F.; Loi, F.; Pajarinen, J.; Nabeshima, A.; Yao, Z.; Hamadouche, M.; Goodman, S.B. The biological response to orthopaedic implants for joint replacement: Part I: Metals. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2017, 105, 2162–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.; Chong, A. Reasons for Implant Removal after Distal Radius Fractures. J. Hand. Surg. Asian Pac. Vol. 2016, 21, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, D.I.; Verhofstad, M.H. Indications for implant removal after fracture healing: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2013, 39, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamineni, S.; Legge, S.; Ware, H. Metallic orthopaedic implants and airport metal detectors. J. Arthroplast. 2002, 17, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).