Development of a Clinical Guideline for Managing Knee Osteoarthritis in Portugal: A Physiotherapist-Centered Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Literature Search

2.2. Evidence Synthesis and Integration

2.3. Development of Recommendations and Support Tools

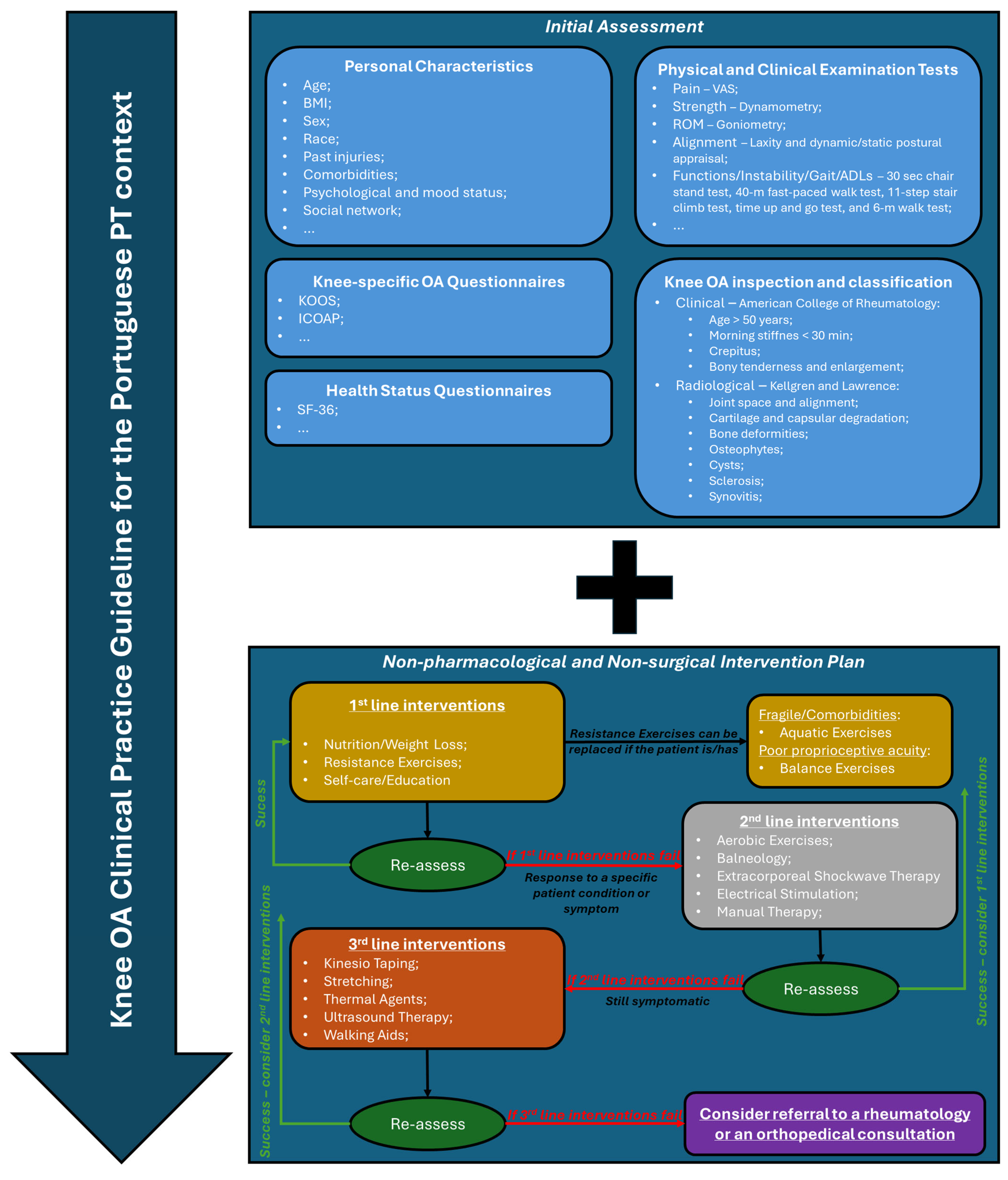

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CPG | Clinical practical guideline |

| EBP | Evidence-based practice |

| ICOAP | Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain |

| KOOS | Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PT | Physiotherapy |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| WOMAC | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index |

References

- Neogi, T.; Zhang, Y. Epidemiology of Osteoarthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finan, P.H.; Buenaver, L.F.; Bounds, S.C.; Hussain, S.; Park, R.J.; Haque, U.J.; Campbell, C.M.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Edwards, R.R.; Smith, M.T. Discordance between Pain and Radiographic Severity in Knee Osteoarthritis: Findings from Quantitative Sensory Testing of Central Sensitization. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakalauskiene, G.; Jauniskiene, D. Osteoarthritis: Etiology, Epidemiology, Impact on the Individual and Society and the Main Principles of Management. Medicina 2010, 46, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel-Pelletier, J.; Pelletier, J.P. Is Osteoarthritis a Disease Involving Only Cartilage or Other Articular Tissues? Eklem Hastalik. Cerrahisi Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 2010, 21, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Felson, D.T.; Hodgson, R. Identifying and Treating Preclinical and Early Osteoarthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 40, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.J.; Schofield, D.; Callander, E. The Individual and Socioeconomic Impact of Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014, 10, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.J.; March, L.; Chew, M. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: A Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 1711–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.; Peleteiro, B.; Araújo, J.; Branco, J.; Santos, R.A.; Ramos, E. The Effect of Osteoarthritis Definition on Prevalence and Incidence Estimates: A Systematic Review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, D.A. Osteoarthritis as an Umbrella Term for Different Subsets of Humans Undergoing Joint Degeneration: The Need to Address the Differences to Develop Effective Conservative Treatments and Prevention Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, C.; Nguyen, C.; Lefevre-Colau, M.-M.; Rannou, F.; Poiraudeau, S. Risk Factors and Burden of Osteoarthritis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Cruz, E.; Nunes da Silva, C.; Canhão, H.; Branco, J.; Nunes, C.; Rodrigues, A. Factors Associated with Clinical and Radiographic Severity in People with Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, S254–S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-Z.; Liang, X.-Z.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Jia, H.-F.; Li, J.-C.; Li, G. Global, Regional, and National Burdens of Osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2021: Findings from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1476853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Tang, H.; Lin, J.; Zeng, R. Temporal Trends in the Disease Burden of Osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2019, and Projections until 2030. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.J.; Santomauro, D.F.; Aali, A.; Abate, Y.H. Global Incidence, Prevalence, Years Lived with Disability (YLDs), Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs), and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for 371 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories and 811 Subnational Locations, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Yin, C.; Sun, X. Global, Regional, and National Trends in Osteoarthritis Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) from 1990 to 2019: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Public Health 2024, 226, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.-X.; Fu, Z.-Y.; Han, R.-Y.; Zhang, J.-L.; Wang, P.; Hou, S.; Pan, H.-F. Trends and Cross-Country Inequalities in the Global Burden of Osteoarthritis, 1990–2019: A Population-Based Study. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Liu, Q.; Yin, H.; Wang, K.; Diao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Guo, A. Prevalence Trends of Site-Specific Osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 1172–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Tan, J.; Xu, K.; Pan, Y.; Xu, P. Global Burden and Socioeconomic Impact of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Comprehensive Analysis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1323091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.; Gal, D.; Barros, H. Prevalência Auto-Declarada de Doenças Reumáticas Numa População Urbana. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2004, 29, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, J.C.; Canhão, H. Estudo Epidemiológico Das Doenças Reumáticas Em Portugal-EpiReumaPt. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2011, 36, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.; Monjardino, M. O Estado da Reumatologia em Portugal; Observatório Nacional das Doenças Reumáticas: Porto, Portugal, 2010; pp. 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, R.; Asch, E.; Bloch, D.; Bole, G.; Borenstein, D.; Brandt, K.; Christy, W.; Cooke, T.D.; Greenwald, R.; Hochberg, M. Development of Criteria for the Classification and Reporting of Osteoarthritis. Classification of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986, 29, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyvang, J.; Hedström, M.; Gleissman, S.A. It’s Not Just a Knee, but a Whole Life: A Qualitative Descriptive Study on Patients’ Experiences of Living with Knee Osteoarthritis and Their Expectations for Knee Arthroplasty. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2016, 11, 30193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.O.; Purdy, R.; Lister, S.; Salter, C.; Fleetcroft, R.; Conaghan, P. Living with Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 43, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, S.; Boutron, I.; Desjeux, D.; Hirschhorn, M.; Meric, G.; Rannou, F.; Poiraudeau, S. Patients’ and Practitioners’ Views of Knee Osteoarthritis and Its Management: A Qualitative Interview Study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellgren, J.H.; Lawrence, J.S. Radiological Assessment of Osteo-Arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felson, D.T. Osteoarthritis of the Knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, J.W.-P.; Schlüter-Brust, K.U.; Eysel, P. The Epidemiology, Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felson, D.T.; Lawrence, R.C.; Hochberg, M.C.; McAlindon, T.; Dieppe, P.A.; Minor, M.A.; Blair, S.N.; Berman, B.M.; Fries, J.F.; Weinberger, M.; et al. Osteoarthritis: New Insights. Part 2: Treatment Approaches. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.E.; Allen, K.D.; Golightly, Y.M.; Goode, A.P.; Jordan, J.M. A Systematic Review of Recommendations and Guidelines for the Management of Osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 43, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringdahl, E.; Pandit, S. Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 83, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.; Kowalczyk, A. Osteoarthritis of the Knee. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2007, 2007, 1121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sinusas, K. Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 85, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sinkov, V.; Cymet, T. Osteoarthritis: Understanding the Pathophysiology, Genetics, and Treatments. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2003, 95, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dziedzic, K.S.; Hill, J.C.; Porcheret, M.; Croft, P.R. New Models for Primary Care Are Needed for Osteoarthritis. Phys. Ther. 2009, 89, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Martins, P.N.; Gonçalves, R.S. Non-Pharmacological and Non-Surgical Interventions to Manage Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: An Umbrella Review 5-Year Update. Osteoarthr. Cartil. Open 2024, 6, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Duarte, J.; Gonçalves, R.S. Non-Pharmacological and Non-Surgical Interventions to Manage Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: An Umbrella Review. Acta Reum. Port 2018, 43, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berteau, J.P. Systematic Narrative Review of Modalities in Physiotherapy for Managing Pain in Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. Medician 2024, 103, e38225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Lu, D.; Chen, S.; Wang, J. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Application of Physical Therapy in Knee Osteoarthritis from 2013 to 2022. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1418433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamtvedt, G.; Dahm, K.T.; Christie, A.; Moe, R.H.; Haavardsholm, E.; Holm, I.; Hagen, K.B. Physical Therapy Interventions for Patients with Osteoarthritis of the Knee: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, M.V.; Kulkarni, C.A.; Wadhokar, O.C.; Wanjari, M.B. Growing Trends in Scientific Publication in Physiotherapy Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Bibliometric Literature Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e48292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; Hu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yan, C.; Peyrodie, L.; Lin, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, S. Physical Therapy Options for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. Medician 2024, 103, e38415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Niu, Y.; Jia, Q. Physical Therapy as a Promising Treatment for Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1011407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, P. Evidence-Based Practice and Physiotherapy in the 1990s. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2001, 17, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.; Stern, P. A Review of the Literature on Evidence-Based Practice in Physical Therapy. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2005, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Dominguez, F.; Tibesku, C.; McAlindon, T.; Freitas, R.; Ivanavicius, S.; Kandaswamy, P.; Sears, A.; Latourte, A. Literature Review to Understand the Burden and Current Non-Surgical Management of Moderate-Severe Pain Associated with Knee Osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Ther. 2024, 11, 1457–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laires, P.A.; Canhão, H.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Eusébio, M.; Gouveia, M.; Branco, J.C. The Impact of Osteoarthritis on Early Exit from Work: Results from a Population-Based Study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, D.A.; Liu, X.; Barnabe, C.; Yee, K.; Faris, P.D.; Barber, C.; Mosher, D.; Noseworthy, T.; Werle, J.; Lix, L. Existing Comorbidities in People with Osteoarthritis: A Retrospective Analysis of a Population-Based Cohort in Alberta, Canada. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e033334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, J.D. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e508–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.; Gray, J.A.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence Based Medicine: What It Is and What It Isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Cairns, J.; Churchill, D.; Cook, D.; Haynes, B.; Hirsh, J.; Irvine, J.; Levine, M.; Levine, M.; Nishikawa, J.; et al. Evidence-Based Medicine. A New Approach to Teaching the Practice of Medicine. JAMA 1992, 268, 2420–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammell, K.W. Using Qualitative Research to Inform the Client-Centred Evidence-Based Practice of Occupational Therapy. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2001, 64, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, W.; Donald, A. Evidence Based Medicine: An Approach to Clinical Problem-Solving. BMJ 1995, 310, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, A.; Silagy, C.A. Evidence-Based Practice in Primary Care; BMJ Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Grimmer, K.; Edwards, I.; Higgs, J.; Trede, F. Challenges in Applying Best Evidence to Physiotherapy. Internet J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2006, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkers, M.P.; Murphy, S.L.; Krellman, J. Evidence-Based Practice for Rehabilitation Professionals: Concepts and Controversies. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, S164–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Wees, P.J.; Moore, A.P.; Powers, C.M.; Stewart, A.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; de Bie, R.A. Development of Clinical Guidelines in Physical Therapy: Perspective for International Collaboration. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feder, G.; Eccles, M.; Grol, R.; Griffiths, C.; Grimshaw, J. Clinical Guidelines: Using Clinical Guidelines. BMJ 1999, 318, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.B.; Graham, I.D.; van den Hoek, J.; Dogherty, E.J.; Carley, M.E.; Angus, V. Guideline Adaptation and Implementation Planning: A Prospective Observational Study. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, J.D.; Cleland, J.A. Development and Application of Clinical Prediction Rules to Improve Decision Making in Physical Therapist Practice. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, C. Translating Evidence into Practice for People with Osteoarthritis of the Hip and Knee. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 26, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livesey, E.A.; Noon, J.M. Implementing Guidelines: What Works. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2007, 92, ep129–ep134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, T.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Qian, T.; Wu, C.; Yue, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y. Quality of Clinical Practice Guidelines Relevant to Rehabilitation of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Clin. Rehabil. 2023, 37, 986–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, A.J.; Gray, B.; Wallis, J.A.; Taylor, N.F.; Kemp, J.L.; Hunter, D.J.; Barton, C.J. Recommendations for the Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conley, B.; Bunzli, S.; Bullen, J.; O’Brien, P.; Persaud, J.; Gunatillake, T.; Dowsey, M.M.; Choong, P.F.M.; Lin, I. Core Recommendations for Osteoarthritis Care: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Arthritis Care Res. 2023, 75, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, L.O.; de Fátima Salvini, T.; McAlindon, T.E. Knee Osteoarthritis: Key Treatments and Implications for Physical Therapy. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, C.; Nelson, A.E.; Neogi, T. Osteoarthritis Treatment Guidelines from Six Professional Societies: Similarities and Differences. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 48, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, P.L.; Hinman, R.S.; Egerton, T.; Dziedzic, K.S.; Bennell, K.L. Identifying and Prioritizing Clinical Guideline Recommendations Most Relevant to Physical Therapy Practice for Hip And/or Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardsson, S.; Johansson, K.; Nilsen, P.; Öberg, B.; Larsson, M.E.H. Determinants of Guideline Use in Primary Care Physical Therapy: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Attitudes, Knowledge, and Behavior. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira de Meneses, S.; Rannou, F.; Hunter, D.J. Osteoarthritis Guidelines: Barriers to Implementation and Solutions. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, I.; Risberg, M.A.; Roos, E.M.; Skou, S.T. A Pragmatic Approach to the Implementation of Osteoarthritis Guidelines Has Fewer Potential Barriers than Recommended Implementation Frameworks. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denoeud, L.; Mazières, B.; Payen-Champenois, C.; Ravaud, P. First Line Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis in Outpatients in France: Adherence to the EULAR 2000 Recommendations and Factors Influencing Adherence. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M.M.; Fillipo, R.; Allen, K.D.; Nelson, A.E.; Skalla, L.A.; Drake, C.D.; Horn, M.E. Use of Implementation Strategies to Promote the Uptake of Knee Osteoarthritis Practice Guidelines and Improve Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Arthritis Care Res. 2024, 76, 1246–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannapfel, P.; Peolsson, A.; Nilsen, P. What Supports Physiotherapists’ Use of Research in Clinical Practice? A Qualitative Study in Sweden. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, T.M.; Costa, L.D.C.M.; Garcia, A.N.; Costa, L.O.P. What Do Physical Therapists Think about Evidence-Based Practice? A Systematic Review. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Martins, P.N.; Pimenta, N.; Gonçalves, R.S. Measuring Evidence-Based Practice in Physical Therapy: A Mix-Methods Study. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jette, D.U.; Bacon, K.; Batty, C.; Carlson, M.; Ferland, A.; Hemingway, R.D.; Hill, J.C.; Ogilvie, L.; Volk, D. Evidence-Based Practice: Beliefs, Attitudes, Knowledge, and Behaviors of Physical Therapists. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 786–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarondo, L.; Grimmer-Somers, K.; Kumar, S. A Systematic Review of the Individual Determinants of Research Evidence Use in Allied Health. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2011, 4, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaithes, L.; Paskins, Z.; Dziedzic, K.; Finney, A. Factors Influencing the Implementation of Evidence-Based Guidelines for Osteoarthritis in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. Musculoskelet. Care 2020, 18, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabana, M.D.; Rand, C.S.; Powe, N.R.; Wu, A.W.; Wilson, M.H.; Abboud, P.-A.C.; Rubin, H.R. Why Don’t Physicians Follow Clinical Practice Guidelines? A Framework for Improvement. Pediatr. Res. 1999, 45, 121A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardsson, S.; Lynch, E.; Dizon, J.M.; Fernandes, J.; Gonzalez-Suarez, C.; Lizarondo, L.; Luker, J.; Wiles, L.; Grimmer, K. Advancing Evidence-Based Practice in Physical Therapy Settings: Multinational Perspectives on Implementation Strategies and Interventions. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, A.R. Translating Knowledge to Practice: Optimizing the Use of Guidelines. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2012, 21, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Marušic, A.; Qaseem, A.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Flottorp, S.; Akl, E.A.; Schünemann, H.J.; Chan, E.S.Y.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. A Reporting Tool for Practice Guidelines in Health Care: The RIGHT Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.S.C.; Stein, A.T. Adaptação Transcultural Do Instrumento Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II (AGREE II) Para Avaliação de Diretrizes Clínicas. Cad. Saude Publica 2014, 30, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meneses, S.R.F.; Goode, A.P.; Nelson, A.E.; Lin, J.; Jordan, J.M.; Allen, K.D.; Bennell, K.L.; Lohmander, L.S.; Fernandes, L.; Hochberg, M.C.; et al. Clinical Algorithms to Aid Osteoarthritis Guideline Dissemination. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016, 24, 1487–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.M.; Martins, P.N.; Pimenta, N.; Gonçalves, R.S. Physical Therapists’ Choices, Views and Agreements Regarding Non-Pharmacological and Non-Surgical Interventions for Knee Osteoarthritis Patients: A Mixed-Methods Study. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2023, 34, 188–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.S.; Pinheiro, J.P.; Cabri, J. Evaluation of Potentially Modifiable Physical Factors as Predictors of Health Status in Knee Osteoarthritis Patients Referred for Physical Therapy. Knee 2012, 19, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, B.; Johnston, M.; Dixon, D. Theoretical Framework and Methodological Development of Common Subjective Health Outcome Measures in Osteoarthritis: A Critical Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, N.J.; Misra, D.; Felson, D.T.; Crossley, K.M.; Roos, E.M. Measures of Knee Function: International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Evaluation Form, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form (KOOS-PS), Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL), Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Activity Rating Scale (ARS), and Tegner Activity Score (TAS). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. 11), S208–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, F.; Hinman, R.S.; Roos, E.M.; Abbott, J.H.; Stratford, P.; Davis, A.M.; Buchbinder, R.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Henrotin, Y.; Thumboo, J.; et al. OARSI Recommended Performance-Based Tests to Assess Physical Function in People Diagnosed with Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroman, S.L.; Roos, E.M.; Bennell, K.L.; Hinman, R.S.; Dobson, F. Measurement Properties of Performance-Based Outcome Measures to Assess Physical Function in Young and Middle-Aged People Known to Be at High Risk of Hip And/or Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliore, A.; Gigliucci, G.; Alekseeva, L.; Avasthi, S.; Bannuru, R.R.; Chevalier, X.; Conrozier, T.; Crimaldi, S.; Damjanov, N.; de Campos, G.C.; et al. Treat-to-Target Strategy for Knee Osteoarthritis. International Technical Expert Panel Consensus and Good Clinical Practice Statements. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2019, 11, 1759720X19893800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R. Non-Operative Management of Knee Osteoarthritis Disability. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 2015, 1, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J.N.; Arant, K.R.; Loeser, R.F. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, R.B.; Casonato, N.A.; Montilha, V.B.; Chaves, T.C.; Mattiello, S.M.; Selistre, L.F.A. Construct Validity and Responsiveness of Performance-Based Tests in Individuals with Knee Osteoarthritis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, 1862–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kao, C.-C.; Liang, H.-W.; Wu, H.-T. Validity of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) Recommended Performance-Based Tests of Physical Function in Individuals with Symptomatic Kellgren and Lawrence Grade 0–2 Knee Osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.P.; Morelli, N.; Prevatte, C.; White, D.; Oliashirazi, A. Validation of Physical Performance Tests in Individuals with Advanced Knee Osteoarthritis. HSS J. 2019, 15, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.D.C.; Perriman, D.M.; Fearon, A.M.; Couldrick, J.M.; Scarvell, J.M. Minimal Important Change and Difference for Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Measurement Tools after Non-Surgical Interventions: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e063026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, H.; Hu, Y.; Shang, S. Measurement Properties of Performance-Based Measures to Assess Physical Function in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 1489–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, F.; Hinman, R.S.; Hall, M.; Terwee, C.B.; Roos, E.M.; Bennell, K.L. Measurement Properties of Performance-Based Measures to Assess Physical Function in Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012, 20, 1548–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez-Oliva, E.; Martínez-Pozas, O.; Sinatti, P.; Martín Carreras-Presas, C.; Cuenca-Zaldívar, J.N.; Turroni, S.; Sánchez Romero, E.A. Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome, Tryptophan-Derived Metabolites, and Osteoarthritis-Related Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Jiang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Mei, Y.; Ding, C.; Chen, M.; et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoarthritis in China (2019 Edition). Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; Honvo, G.; Veronese, N.; Arden, N.K.; Branco, J.; Curtis, E.M.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Pelletier, J.-P.; et al. An Updated Algorithm Recommendation for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2019, 49, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseng, T.; Vliet Vlieland, T.P.M.; Battista, S.; Beckwée, D.; Boyadzhieva, V.; Conaghan, P.G.; Costa, D.; Doherty, M.; Finney, A.G.; Georgiev, T.; et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Non-Pharmacological Core Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: 2023 Update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pers, Y.-M.; Nguyen, C.; Borie, C.; Daste, C.; Kirren, Q.; Lopez, C.; Ouvrard, G.; Ruscher, R.; Argenson, J.-N.; Bardoux, S.; et al. Recommendations from the French Societies of Rheumatology and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation on the Non-Pharmacological Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 67, 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariani, A.; Manara, M.; Fioravanti, A.; Iannone, F.; Salaffi, F.; Ughi, N.; Prevete, I.; Bortoluzzi, A.; Parisi, S.; Scirè, C.A. The Italian Society for Rheumatology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Knee, Hip and Hand Osteoarthritis. Reumatismo 2019, 71, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Doormaal, M.C.M.; Meerhoff, G.A.; Vliet Vlieland, T.P.M.; Peter, W.F. A Clinical Practice Guideline for Physical Therapy in Patients with Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis. Musculoskelet. Care 2020, 18, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Kraus, V.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Abbott, J.H.; Bhandari, M.; et al. OARSI Guidelines for the Non-Surgical Management of Knee, Hip, and Polyarticular Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosseau, L.; Taki, J.; Desjardins, B.; Thevenot, O.; Fransen, M.; Wells, G.A.; Imoto, A.M.; Toupin-April, K.; Westby, M.; Gallardo, I.C.Á.; et al. The Ottawa Panel Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Part One: Introduction, and Mind-Body Exercise Programs. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosseau, L.; Taki, J.; Desjardins, B.; Thevenot, O.; Fransen, M.; Wells, G.A.; Mizusaki Imoto, A.; Toupin-April, K.; Westby, M.; Álvarez Gallardo, I.C.; et al. The Ottawa Panel Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Part Two: Strengthening Exercise Programs. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosseau, L.; Taki, J.; Desjardins, B.; Thevenot, O.; Fransen, M.; Wells, G.A.; Mizusaki Imoto, A.; Toupin-April, K.; Westby, M.; Álvarez Gallardo, I.C.; et al. The Ottawa Panel Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Part Three: Aerobic Exercise Programs. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rillo, O.; Riera, H.; Acosta, C.; Liendo, V.; Bolaños, J.; Monterola, L.; Nieto, E.; Arape, R.; Franco, L.M.; Vera, M.; et al. PANLAR Consensus Recommendations for the Management in Osteoarthritis of Hand, Hip, and Knee. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 22, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncer, T.; Cay, F.H.; Altan, L.; Gurer, G.; Kacar, C.; Ozcakir, S.; Atik, S.; Ayhan, F.; Durmaz, B.; Eskiyurt, N.; et al. 2017 Update of the Turkish League Against Rheumatism (TLAR) Evidence-Based Recommendations for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 1315–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, G.W.; McMaster, W.C.; Goodman, F. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Non-Surgical Management of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis; Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Non-Arthroplasty) Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Rosemont, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G.; Neilson, J.; Cottrell, E.; Hoole, S. Osteoarthritis in People over 16: Diagnosis and Management—Updated Summary of NICE Guidance. BMJ 2023, 380, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeap, S.S.; Abu Amin, S.R.; Baharuddin, H.; Koh, K.C.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, V.K.M.; Mohamad Yahaya, N.H.; Tai, C.C.; Tan, M.P. A Malaysian Delphi Consensus on Managing Knee Osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guideline for the Management of Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis, 2nd ed.; RACGP: East Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/knee-and-hip-osteoarthritis/about-this-guideline (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Lim, W.B.; Al-Dadah, O. Conservative Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review of the Literature. World J. Orthop. 2022, 13, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Zan, Q.; Wang, B.; Fan, X.; Chen, Z.; Yan, F. Efficacy of Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomey, C.M.; Kennedy, N.; MacFarlane, A.; Glynn, L.; Forbes, J.; Skou, S.T.; Roos, E.M. Implementation of clinical guidelines for osteoarthritis together (IMPACT): Protocol for a participatory health research approach to implementing high value care. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord 2022, 23, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafañe, J.H.; Valdes, K.; Pedersini, P.; Berjano, P. Osteoarthritis: A Call for Research on Central Pain Mechanism and Personalized Prevention Strategies. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Cruz, E.B.; Canhão, H.; Branco, J.; Nunes, C. Driving Factors for the Utilisation of Healthcare Services by People with Osteoarthritis in Portugal: Results from a Nationwide Population-Based Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirman, S.W.; Baumann, A.A.; Miller, C.J. The FRAME: An Expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-Based Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mello, N.F.; Silva, S.N.; Gomes, D.F.; Girardi, J.d.M.; Barreto, J.O.M. Models and frameworks for assessing the implementation of clinical practice guidelines: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2024, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Cruz, E.B.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.; Gomes, L.A.; Donato, H.; Nunes, C. Models of Care for Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis in Primary Healthcare: A Scoping Review Protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kredo, T.; Bernhardsson, S.; Machingaidze, S.; Young, T.; Louw, Q.; Ochodo, E.; Grimmer, K. Guide to Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Current State of Play. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2016, 28, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, V.C.; Silva, S.N.; Carvalho, V.K.; Zanghelini, F.; Barreto, J.O. Strategies for the Implementation of Clinical Practice Guidelines in Public Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.; Campbell, M.; Copeland, L.; Craig, P.; Movsisyan, A.; Hoddinott, P.; Littlecott, H.; O’Cathain, A.; Pfadenhauer, L.; Rehfuess, E.; et al. Adapting Interventions to New Contexts—The ADAPT Guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Interventions | Evidence Level | Clinical Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Umbrella Review [36] | Local Practice [87] | |

| Acupuncture | Weak | Weak |

| Aerobic Exercise | - | Moderate |

| Aquatic Therapy | Moderate | Strong |

| Baduanjin | Weak | - |

| Balance Exercise | Moderate | Moderate |

| Balneology/Spa | Moderate | Weak |

| Blood Flow Restriction Therapy | Weak | - |

| Braces | - | Weak |

| Circuit-based Exercise | Weak | - |

| Dry Needling | Weak | - |

| Electrical Stimulation Therapies | Weak | Moderate |

| Electroacupuncture | - | Weak |

| Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy | Moderate | Weak |

| Insoles | - | Weak |

| Kinesio Tape | Weak | Moderate |

| Laser Therapy | Weak | Weak |

| Magnetic Field Therapy | Weak | Weak |

| Manual Therapy | Weak | Strong |

| Moxibustion | - | Weak |

| Non-elastic Tape | - | Weak |

| Nutrition/Weight Loss | Strong | Strong |

| Resistance Training | Strong | Strong |

| Self-care/Education | Strong | Strong |

| Stretching | - | Strong |

| Tai Chi | Moderate | Weak |

| Thermal Agents | Weak | Moderate |

| Ultrasonic Therapy | Weak | Moderate |

| Walking Aids | - | Moderate |

| Whole-body Vibration | Weak | Weak |

| Wu Qin Xi | Weak | - |

| Yoga | Weak | Weak |

| Number | Recommendation | Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The primary objectives in managing patients with knee OA are to alleviate pain, enhance and maintain muscular strength, improve or preserve ROM, support functional independence, and optimize QoL. To achieve these outcomes, a comprehensive treatment strategy should prioritize non-pharmacologic interventions, followed by pharmacologic therapies, and surgical options when indicated. Moreover, the therapeutic approach must be individualized to address each patient’s specific needs. | Strong recommendation |

| 2. | In individuals with knee OA, assessments should follow a biopsychosocial framework, including:

| Strong recommendation |

| 3. | Knee OA management should be tailored to the individual according to:

| Strong recommendation |

| 4. | Patients with knee OA should receive a personalized management plan that incorporates core non-pharmacological and non-surgical interventions. The intervention plan should be multicomponent and individualized, based on shared decision-making taking into account the individual’s needs, preferences, and capabilities. The core interventions should include:

| Strong recommendation |

| 5. | In addition to the core interventions and to respond to a specific condition, the following could be incorporated:

| Strong recommendation |

| 6. | If core and adjunctive interventions do not adequately address the patient’s signs, symptoms, and clinical needs, the following could be performed:

| Moderate recommendation |

| 7. | If the patient remains symptomatic, the following could be considered:

| Weak recommendation |

| 8. | If non-pharmacological and non-surgical interventions fail to adequately address the patient’s needs, referral to an orthopedic or rheumatology specialist should be considered to:

| Strong recommendation |

| Intervention | Current (2025) | SFR/SOFMER [107] (2024) | NICE [118] (2023) | EULAR [106] (2023) | AAOS [117] (2021) | MAHTAS [119] (2021) | CRIECCSMHEA [104] (2020) | VA/DOD [116] (2020) | KNGF [109] (2020) | ACR [103] (2019) | ESCEO [105] (2019) | ISR [108] (2019) | OARSI [110] (2019) | RACGP [120] (2018) | TLAR [115] (2017) | Ottawa [111,112,113] (2017) | PANLAR [114] (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Self-care/Education |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Nutrition/Weight loss |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||

| Balance exercises |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||||||||

| Manual therapy |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||

| Balneology |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Electrical Stimulation |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||||||||

| ESWT |  |  | |||||||||||||||

| Walking aids |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||||

| Taping |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||||

| Thermal agents |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||||||||

| Ultrasound |  |  | |||||||||||||||

| Stretching |  |  | |||||||||||||||

| Braces |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||

| Tai chi |  |  |  |  |  |  | |||||||||||

| Acupuncture |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||||||

| Insoles |  |  |  |  |  | ||||||||||||

| Yoga |  |  |  |  | |||||||||||||

| Laser |  |

—“Gold”: should do/strong recommendation;

—“Gold”: should do/strong recommendation;  —“Silver”: could do/moderate recommendation;

—“Silver”: could do/moderate recommendation;  —“Bronze”: uncertain/weak recommendation; Abbreviations: AAOS—American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; ACR—American College of Rheumatology; CRIECCSMHEA—Chinese Rheumatology and Immunology Expert Committee of the Cross-Strait Medical and Health Exchange Association; ESCEO—European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases; ESWT—Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy; EULAR—European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; ISR—Italian Society for Rheumatology; KNGF—Royal Dutch Society for Physiotherapy; MAHTAS—Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section; NICE—National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OARSI—Osteoarthritis Research Society International; PANLAR—Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology; RACGP—Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; SFR/SOFMER—French Society of Rheumatology and the French Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; TLAR—Turkish League Against Rheumatism; VA/DOD—United States Department of Veterans Affairs and Defense; Note: Only the most recent guideline from each society are exposed. Only the recommended interventions are shown. The guidelines’ recommendations against an intervention are not displayed.

—“Bronze”: uncertain/weak recommendation; Abbreviations: AAOS—American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; ACR—American College of Rheumatology; CRIECCSMHEA—Chinese Rheumatology and Immunology Expert Committee of the Cross-Strait Medical and Health Exchange Association; ESCEO—European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases; ESWT—Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy; EULAR—European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; ISR—Italian Society for Rheumatology; KNGF—Royal Dutch Society for Physiotherapy; MAHTAS—Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section; NICE—National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OARSI—Osteoarthritis Research Society International; PANLAR—Pan-American League of Associations for Rheumatology; RACGP—Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; SFR/SOFMER—French Society of Rheumatology and the French Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; TLAR—Turkish League Against Rheumatism; VA/DOD—United States Department of Veterans Affairs and Defense; Note: Only the most recent guideline from each society are exposed. Only the recommended interventions are shown. The guidelines’ recommendations against an intervention are not displayed.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira, R.M.; Gonçalves, R.S. Development of a Clinical Guideline for Managing Knee Osteoarthritis in Portugal: A Physiotherapist-Centered Approach. Osteology 2025, 5, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5030023

Ferreira RM, Gonçalves RS. Development of a Clinical Guideline for Managing Knee Osteoarthritis in Portugal: A Physiotherapist-Centered Approach. Osteology. 2025; 5(3):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Ricardo Maia, and Rui Soles Gonçalves. 2025. "Development of a Clinical Guideline for Managing Knee Osteoarthritis in Portugal: A Physiotherapist-Centered Approach" Osteology 5, no. 3: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5030023

APA StyleFerreira, R. M., & Gonçalves, R. S. (2025). Development of a Clinical Guideline for Managing Knee Osteoarthritis in Portugal: A Physiotherapist-Centered Approach. Osteology, 5(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/osteology5030023