Computational Models for the Vibration and Modal Analysis of Silica Nanoparticle-Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Elastic and Viscoelastic Foundation Effects

Abstract

1. Research Background

2. Materials and Methods

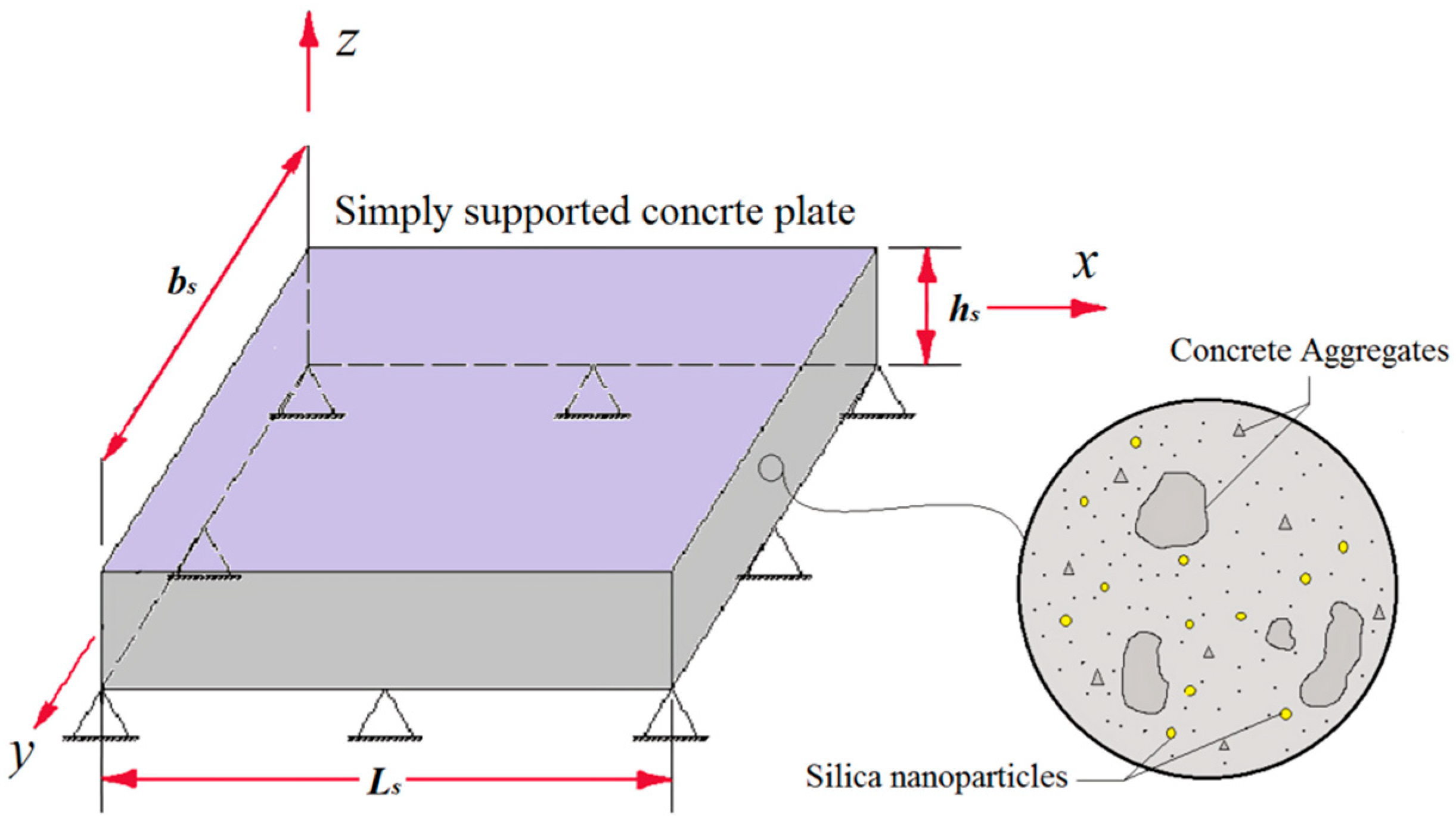

2.1. Kinematics of the Reinforced Concrete Plate

2.2. Stress–Strain Relations

2.3. Homogenization Model for NS Reinforced Concrete Slab

- Phase I—Homogeneous concrete matrix: At the initial stage, the concrete is treated as a homogeneous, isotropic material representing conventional unreinforced concrete. This baseline phase serves as a reference for evaluating the effect of NS inclusion on the slab’s overall stiffness and dynamic response.

- Phase II—Bi-phasic composite material: Upon introducing NS particles, the medium is regarded as a two-phase composite consisting of a cementitious matrix and dispersed nanoparticles. The nanoparticle volume fraction varies from 0% (pure concrete) to 30%, allowing the investigation of how different reinforcement levels influence the composite stiffness, flexural rigidity, and vibration characteristics.

- Spherical morphology of nanoparticles: The NS are assumed to be perfectly spherical for analytical simplicity. Although real nanoparticles may slightly deviate from this ideal shape, such approximations effectively capture the primary mechanisms of particle packing, pore refinement, and matrix densification, with minimal influence on the overall macroscopic response.

- Random distribution within the matrix: The nanoparticles are assumed to be uniformly and randomly dispersed throughout the concrete without forming clusters or agglomerates. This assumption ensures an isotropic reinforcement effect and simplifies the homogenization procedure, while still providing a physically realistic representation of nano-reinforced concrete behavior.

2.4. Equations of Motion of the RC Slab

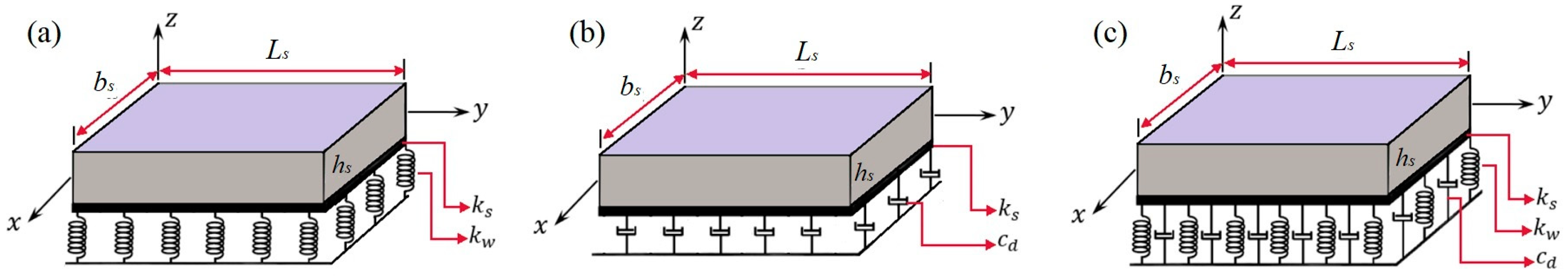

- Winkler elastic foundation: , , .

- Winkler–Pasternak elastic foundation: , , .

- Visco–Pasternak foundation: , , .

- Visco–Winkler–Pasternak foundation (three-parameter viscoelastic model): , , .

2.5. Closed Form Solutions for a Simply Supported RC Slab

3. Results and Discussions

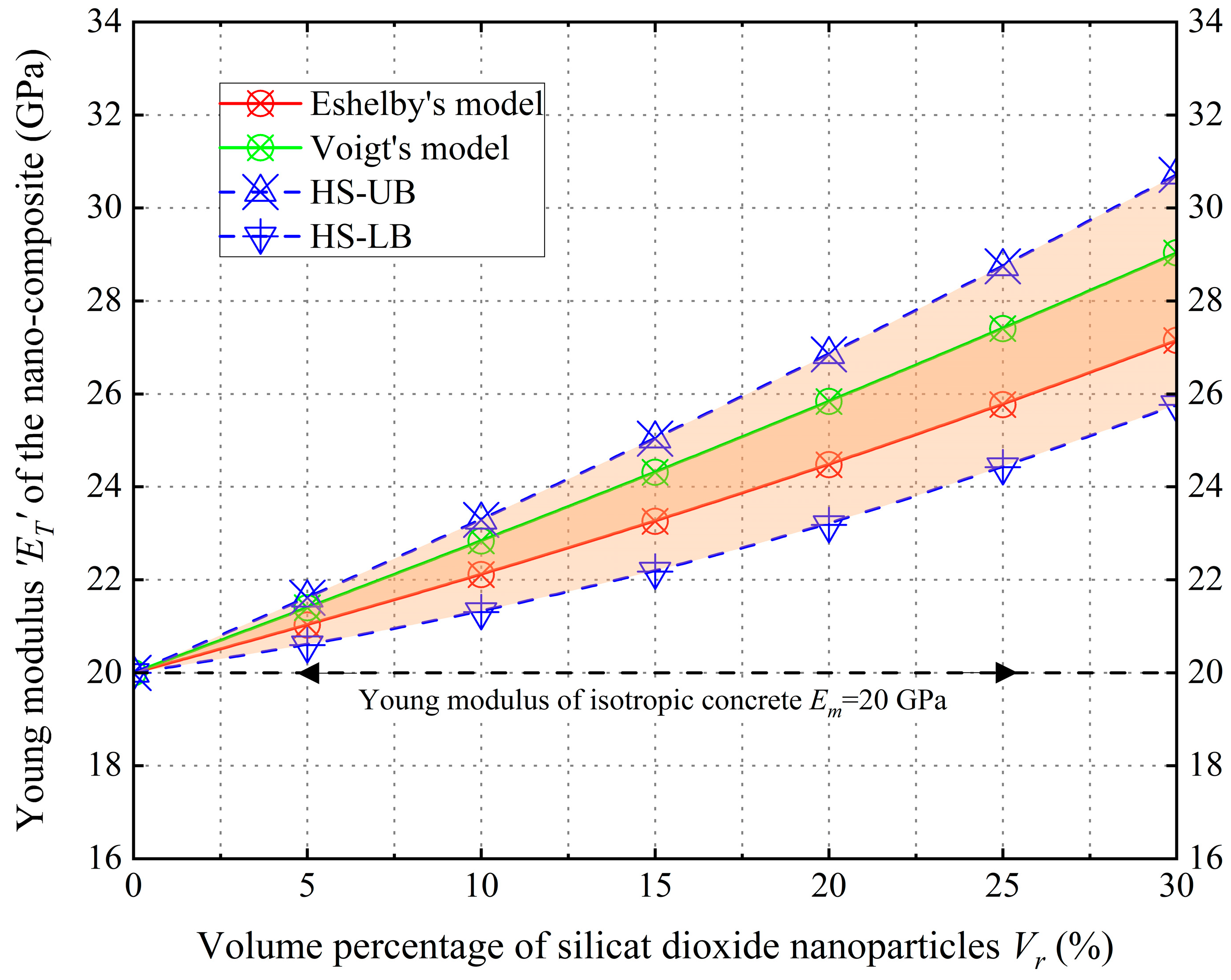

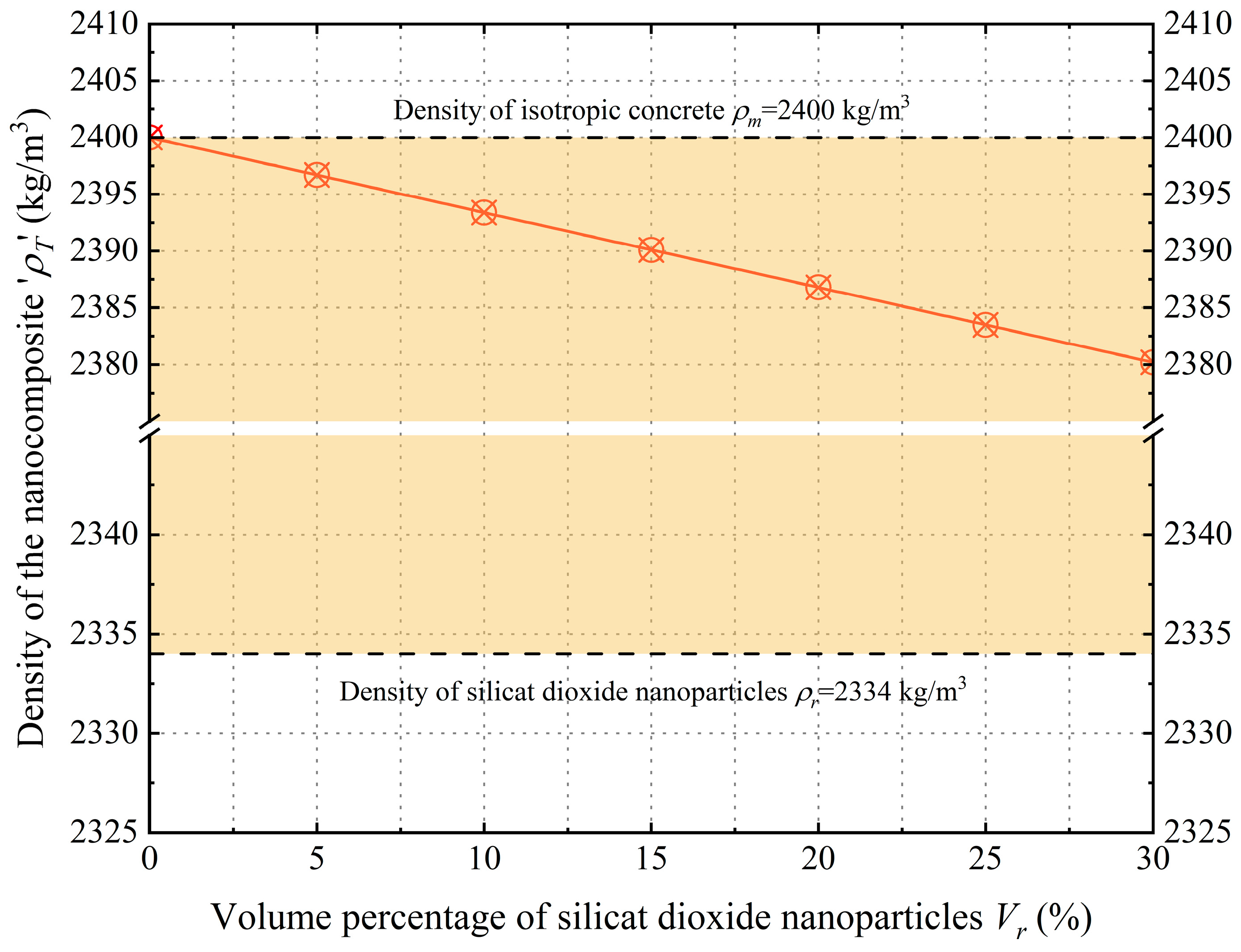

3.1. Material Characterization

3.2. Validation of the Plate Theory

- For the dynamic analysis:

- For the different foundations:

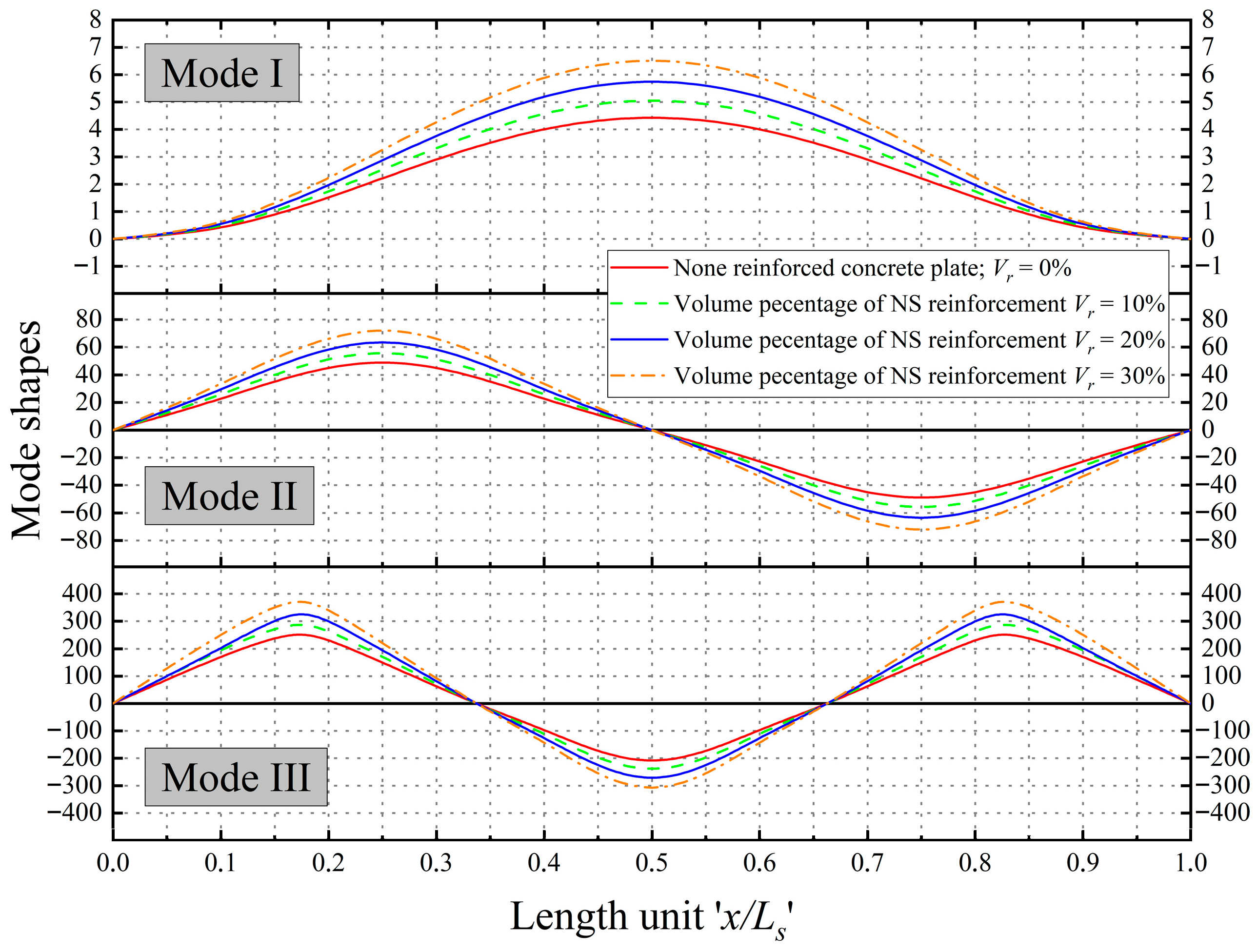

3.3. Dynamic Analysis of RC Slabs Reinforced with SiO2 Nanoparticles

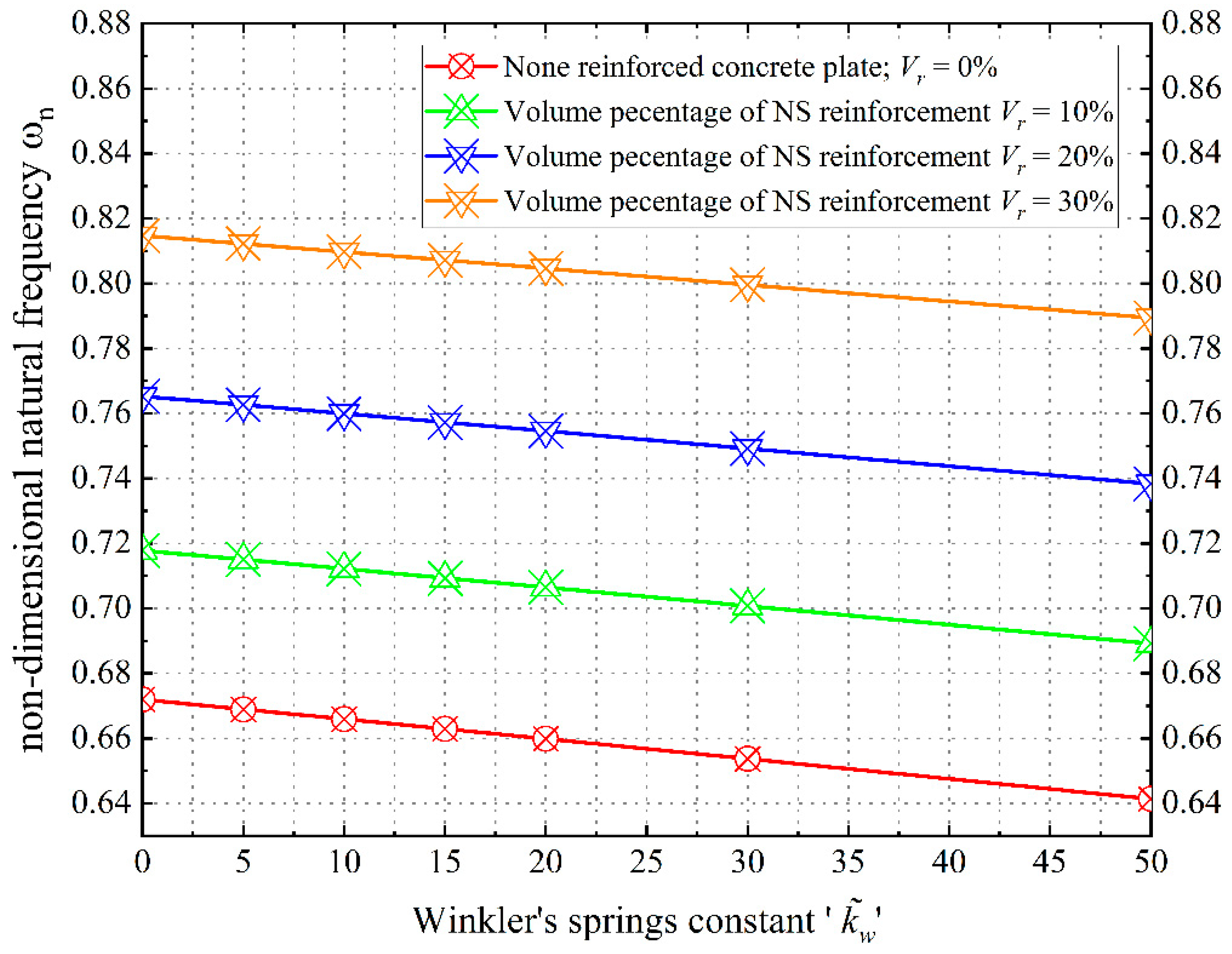

3.4. The Effect of Winkler–Pasternak’s Elastic Foundation

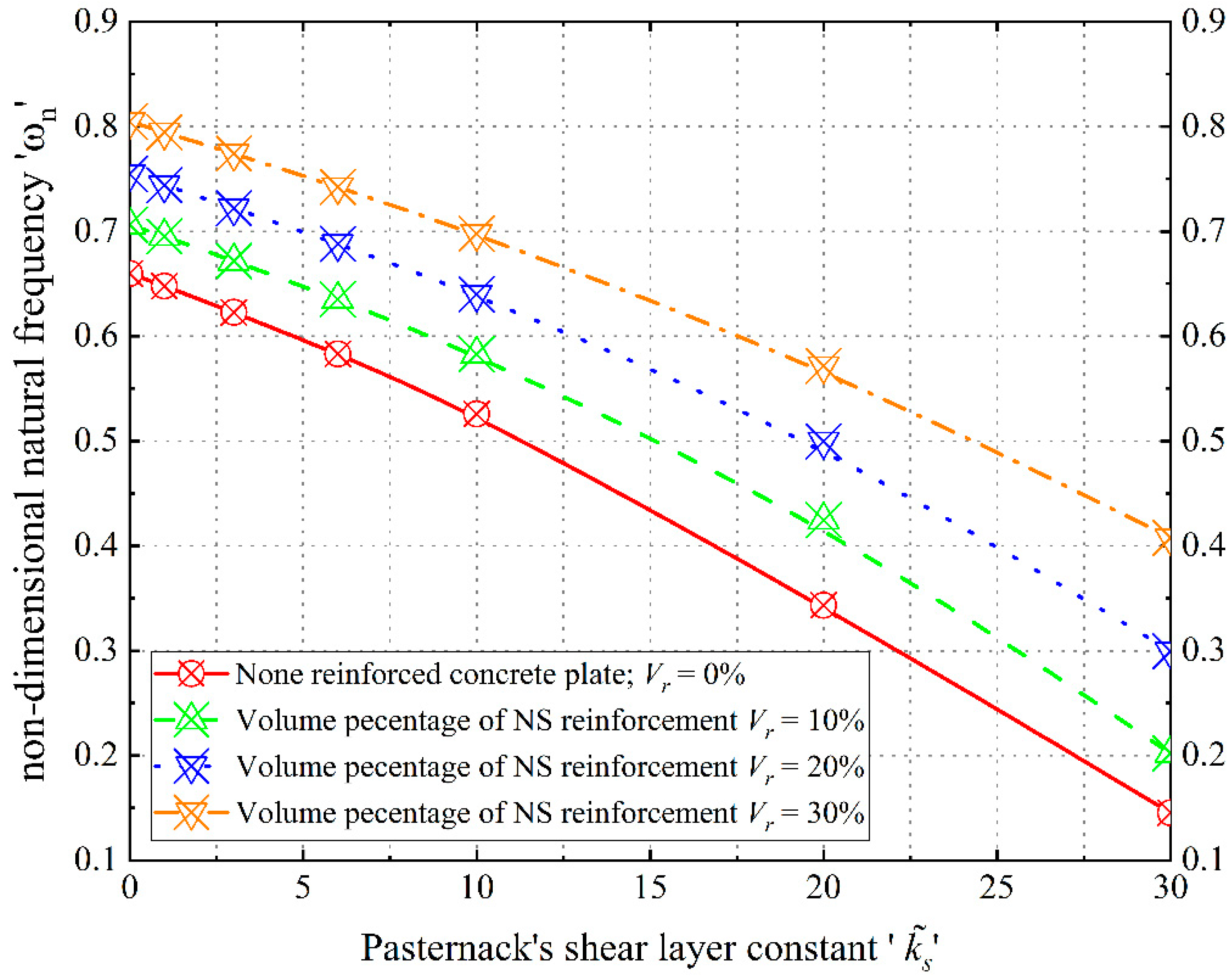

3.5. The Effect of the Visco–Pasternak Foundation

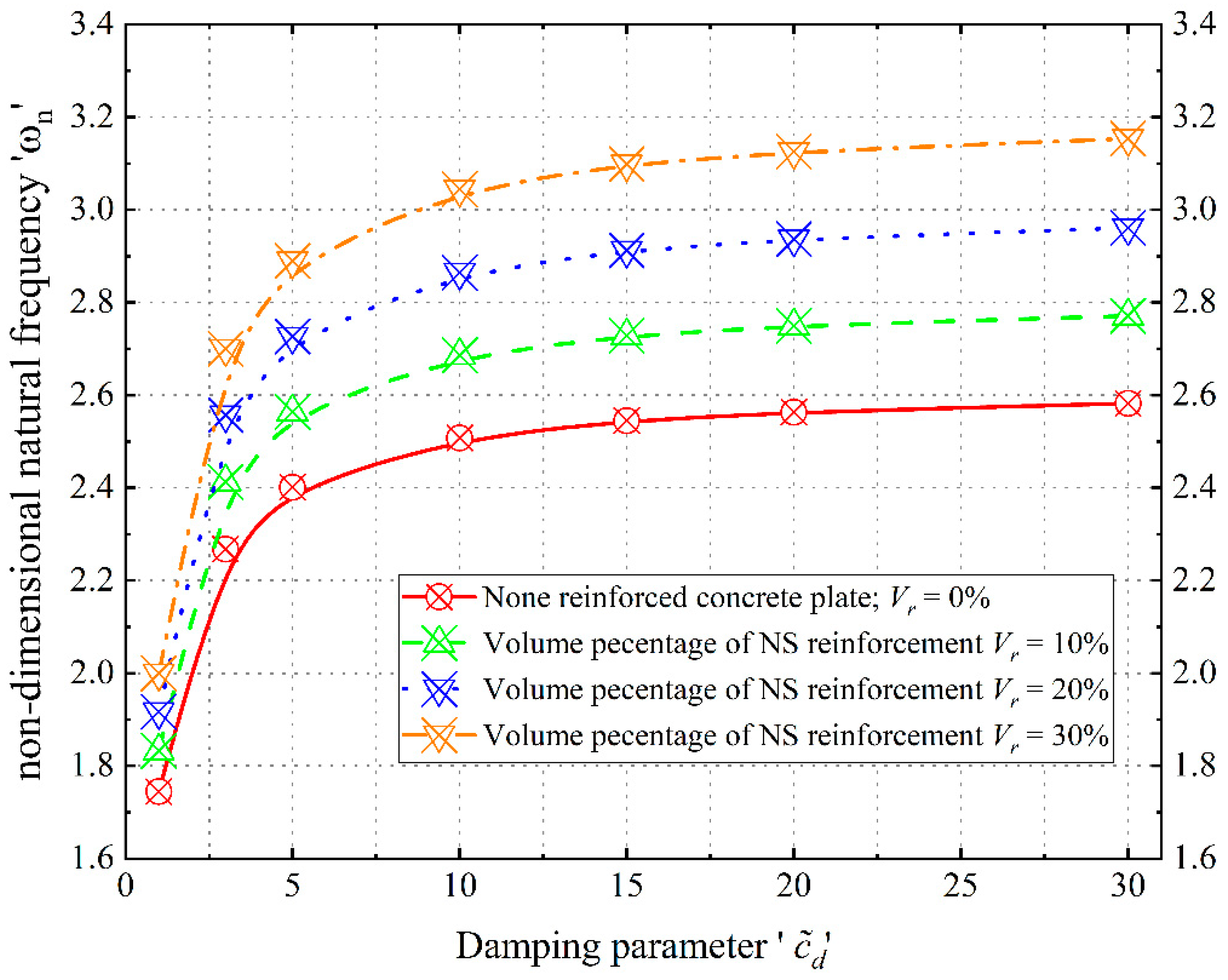

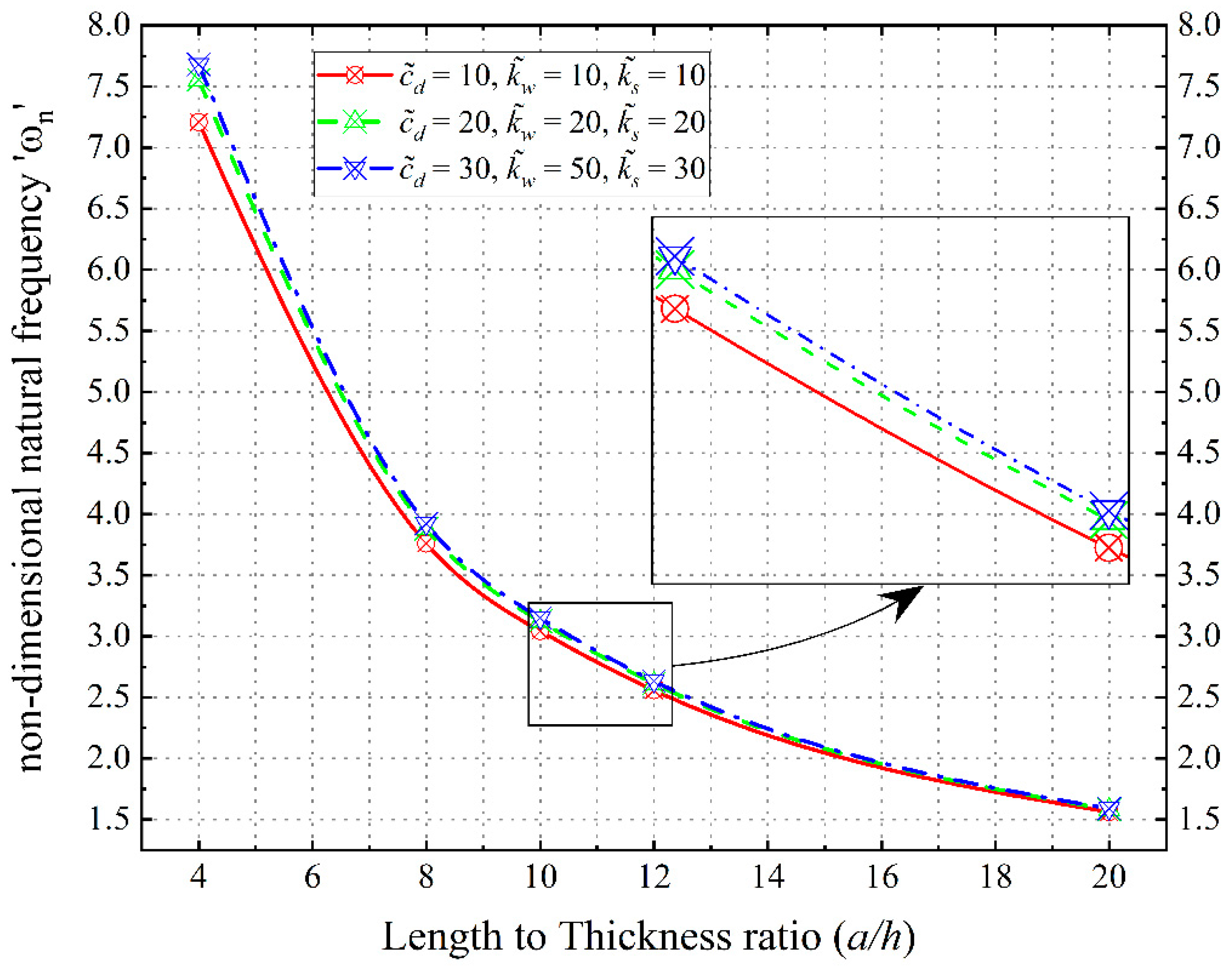

3.6. Effect of Visco–Winkler–Pasternak Foundation

4. Conclusions

- Consistent with existing understanding; our analytical homogenization revealed that the addition of NS to concrete matrices significantly enhances their elastic properties, a correlation observed in relation to the volume of these reinforcements.

- Infusing high volumes of NS into a concrete matrix (Vr = 30 wt%) can increase the elastic properties of the nano-infused matrix by up to 26% and also enhance the elastic stiffness of the nano-infused concrete matrix by up to 30%.

- Dynamic analysis has shown a notable enhancement in plate dynamics with the incorporation of nano-SiO2, with the most significant improvement observed when incorporating 30 wt% of NS, resulting in an increase in plate natural frequency by up to 18%.

- Incorporating NS as reinforcement in concrete slabs significantly impacts and alters the inherent mode shapes of the plates, rendering them more valuable, Optimal amount of NS (Vr = 30 wt%) results in a significant increase of up to 32% in all studied mode shapes of the nano-composite plate.

- Contrasting the shear layer and spring constants of the elastic foundation, the damping parameter within the viscous foundation significantly contributes to increased frequencies, thereby enhancing plate stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Setareh, M.; Darvas, R. Concrete Structures, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ma, H.; Hou, D. Advanced Concrete Technology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; p. 624. ISBN 978-1-119-80619-6. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, J.; Choo, B.S. Advanced Concrete Technology Constituent Materials, 1st ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2003; ISBN 9780750651035. [Google Scholar]

- Balaguru, P.; Chong, K. Nanotechnology and Concrete: Research Opportunities; ACI-International: Montreal, QC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, J.; Silvestre, N.; De Brito, J. Review on concrete nanotechnology. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2015, 20, 455–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khitab, A.; Anwar, W. Advanced Research on Nanotechnology for Civil Engineering Applications; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2016; p. 339. ISBN 9781522503446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, P. Nanotechnology in Construction, 1st ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2004; Volume 292, p. 412. ISBN 0854046232. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A.N.; Attar, A.A.; Algburi, S.; Ahmed, O.K. Comparative study of the effect of silica nanoparticles and polystyrene on the properties of concrete. Results Mater. 2023, 18, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhilash, P.; Nayak, D.K.; Sangoju, B.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, V. Effect of nano-silica in concrete; a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 278, 122347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, S.; Nematzadeh, M. Mechanical properties and durability of high-strength concrete containing macro-polymeric and polypropylene fibers with nano-silica and silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhuang, C.; Chen, Y.; Hu, R. Mechanical Properties of Nano SiO2 and Carbon Fiber Reinforced Concrete after Exposure to High Temperatures. Materials 2019, 12, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behfarnia, K.; Rostami, M. Effects of micro and nanoparticles of SiO2 on the permeability of alkali activated slag concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 131, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Wu, G.Y.; Fang, C.; Li, D.W.; Han, N.X.; Xing, F. Effect of nano-SiO2 on strength, shrinkage and cracking sensitivity of lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 175, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaye, L.; Ansari, W.S.; Gebreyouhannes, E.; Hussain, Z.; Naseem, A. Role of coarse aggregate sizes in evaluating the bond-slip mechanism of reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloo, A.; Mobini, M.H.; Hosseini, P. Influence of different types of nano-SiO2 particles on properties of high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicakci Sidar, N.; Baran, S.; Boyaci, B.; Turkmenoglu Hasan, N.; Turan, O.T.; Atahan Hakan, N. Evaluation of Microsilica and Nanosilica on Bond Properties between Moderate–High Strength Concrete and Plain–Ribbed Steel Rebar. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04023553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukharjee, B.B.; Barai, S.V. Influence of Incorporation of Colloidal Nano-Silica on Behaviour of Concrete. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2020, 44, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonggui, W.; Shuaipeng, L.; Hughes, P.; Yuhui, F. Mechanical properties and microstructure of basalt fibre and nano-silica reinforced recycled concrete after exposure to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247, 118561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Their, J.M.; Özakça, M. Developing geopolymer concrete by using cold-bonded fly ash aggregate, nano-silica, and steel fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 180, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuaklong, P.; Sata, V.; Wongsa, A.; Srinavin, K.; Chindaprasirt, P. Recycled aggregate high calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete with inclusion of OPC and nano-SiO2. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 174, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan-Nattaj, F.; Nematzadeh, M. The effect of forta-ferro and steel fibers on mechanical properties of high-strength concrete with and without silica fume and nano-silica. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 137, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, P.; Ramachandra Murthy, A.; Sundar Kumar, S.; Mohammed Saffiq Reheman, M.; Iyer, N.R. Effect of nanosilica on durability and mechanical properties of high-strength concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2016, 68, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithra, S.; Senthil Kumar, S.R.R.; Chinnaraju, K. The effect of Colloidal Nano-silica on workability, mechanical and durability properties of High Performance Concrete with Copper slag as partial fine aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, M.; Mansouri, E.; Sharifipour, M.; Pouladkhan, A.R. Mechanical, rheological, durability and microstructural properties of high performance self-compacting concrete containing SiO2 micro and nanoparticles. Mater. Des. 2012, 34, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supit, S.W.M.; Shaikh, F.U.A. Durability properties of high volume fly ash concrete containing nano-silica. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 2431–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, N.; Abbas, M.L.; Atmaca, A. Effects of nano-silica on the gas permeability, durability and mechanical properties of high-strength lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sha, D.; Li, Q.; Zhao, S.; Ling, Y. Effect of Nano Silica Particles on Impact Resistance and Durability of Concrete Containing Coal Fly Ash. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beigi, M.H.; Berenjian, J.; Lotfi Omran, O.; Sadeghi Nik, A.; Nikbin, I.M. An experimental survey on combined effects of fibers and nanosilica on the mechanical, rheological, and durability properties of self-compacting concrete. Mater. Des. 2013, 50, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Wu, P.; Li, Z.-X. Influences of nano-particles on dynamic strength of ultra-high performance concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 91, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, M.H.; Mutalib, A.A.; Hamid, R.; Raman, S.N. Dynamic properties of high volume fly ash nanosilica (HVFANS) concrete subjected to combined effect of high strain rate and temperature. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, M.H.; Abdulhadi, A.M.; Abbood, I.S.; Mutalib, A.A.; Yaseen, Z.M. Late Age Dynamic Strength of High-Volume Fly Ash Concrete with Nano-Silica and Polypropylene Fibres. Crystals 2020, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shi, C.; Khayat, K.H.; Xie, L. Effect of SCM and nano-particles on static and dynamic mechanical properties of UHPC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 182, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, N.; Wang, C. Analysis and Design of Plated Structures: Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN 9871845691165. [Google Scholar]

- Harrat, Z.R.; Amziane, S.; Krour, B.; Bouiadjra, M.B. On the static behavior of nano Si02 based concrete beams resting on an elastic foundation. Comput. Concr. 2021, 27, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatbi, M.; Krour, B.; Benatta, M.A.; Harrat, Z.R.; Amziane, S.; Bouiadjra, M.B. Bending analysis of nano-SiO2 reinforced concrete slabs resting on elastic foundation. Struct. Eng. Mech. Int. J. 2022, 84, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dine Elhennani, S.; Harrat, Z.R.; Chatbi, M.; Belbachir, A.; Krour, B.; Işık, E.; Harirchian, E.; Bouremana, M.; Bachir Bouiadjra, M. Buckling and Free Vibration Analyses of Various Nanoparticle Reinforced Concrete Beams Resting on Multi-Parameter Elastic Foundations. Materials 2023, 16, 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassas, M.R.; Bidgoli, M.R.; Kolahchi, R. Forced vibration analysis of concrete slabs reinforced by agglomerated SiO2 nanoparticles based on numerical methods. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Moradi, Z.; Safa, M.; Khadimallah, M.A. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of thermally deformed beams subjected to uniform loading resting on nonlinear viscoelastic foundation. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 2022, 95, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Lashini, H.; Habibi, M.; Safarpour, H. Influence of Viscoelastic Foundation on Dynamic Behaviour of the Double Walled Cylindrical Inhomogeneous Micro Shell Using MCST and with the Aid of GDQM. J. Solid Mech. 2019, 11, 440–453. [Google Scholar]

- Alnujaie, A.; Akbas, S.D.; Eltaher, M.A.; Assie, A. Forced vibration of a functionally graded porous beam resting on viscoelastic foundation. Geomech. Eng. 2021, 24, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, A.A.; Nabawy, A.E.; Abdelhaleem, A.M.; Alieldin, S.S.; Eltaher, M.A. Nonlinear dynamics of viscoelastic flexible structural systems by finite element method. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, M.; Zenkour, A.M. Size-dependent free vibration and dynamic analyses of piezo-electro-magnetic sandwich nanoplates resting on viscoelastic foundation. Phys. B Condens. 2017, 521, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, M.; Zenkour, A.M. Vibration and bending analyses of magneto–electro–thermo-elastic sandwich microplates resting on viscoelastic foundation. Appl. Phys. A 2017, 123, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenkour, A.M.; El-Shahrany, H.D. Controlled motion of viscoelastic fiber-reinforced magnetostrictive sandwich plates resting on visco-Pasternak foundation. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2022, 29, 2312–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.N. A Simple Higher-Order Theory for Laminated Composite Plates. J. Appl. Mech. 1984, 51, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touratier, M. A generalization of shear deformation theories for axisymmetric multilayered shells. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1992, 29, 1379–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hua, H.; Shen, R. Dynamic Stiffness Analysis of a Beam Based on Trigonometric Shear Deformation Theory. J. Vib. Acoust. 2007, 130, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimpi, R.P. Refined plate theory and its variants. AIAA J. 2002, 40, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T.; Kim, S.-E. A simple quasi-3D sinusoidal shear deformation theory for functionally graded plates. Compos. Struct. 2013, 99, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J.D. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1957, 241, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, D.B. Some physical properties of two-phase crystal-glass solids. Sci. Ceram. 1962, 1, 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Horszczaruk, E.; Łukowski, P.; Seul, C. Influence of Dispersing Method on the Quality of Nano-Admixtures Homogenization in Cement Matrix. Materials 2020, 13, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumyan, S.A.; Muradyan, N.G.; Kalantaryan, M.A.; Arzumanyan, A.A.; Melikyan, Y.; Laroze, D.; Barseghyan, M.G. Simultaneous Effect of Diameter and Concentration of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Cement Mortars: With and without Biosilica. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Lee, H.-S.; Seo, J.; Kang, Y.-H.; Kim, W.; Kang, T.H.K. State-of-the-Art of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Optimal Method for their Dispersion for Construction-Related Applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, G.B.; Costa, S.M.M.; Gumieri, A.G.; Calixto, J.M.F.; França, F.C.; Silva, C.; Quinõnes, A.D. Mechanical properties and microstructure of high performance concrete containing stabilized nano-silica. Matéria (Rio J.) 2017, 22, e11824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, S.; Seo, J.-W.T.; Corr, D.; Hersam, M.C.; Shah, S.P. Dispersion of CaCO3 nanoparticles by sonication and surfactant treatment for application in fly ash–cement systems. Mater. Struct. 2014, 47, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, D.; Clyne, T.W. An Introduction to Composite Materials, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W. Ueber die Beziehung zwischen den beiden Elasticitätsconstanten isotroper Körper. Ann. Phys. 1889, 274, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W. Lehrbuch der kristallphysik; B.G. Teubner: Berlin, Germany; Leipzig, Germany, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.M. Mechanics of Composite Materials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 1315272989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashin, Z.; Shtrikman, S. A variational approach to the theory of the elastic behaviour of multiphase materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1963, 11, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, H.A.; Aghdam, M.M.; Sadighi, M. Free vibration analysis of thick viscoelastic composite plates on visco-Pasternak foundation using higher-order theory. Compos. Struct. 2017, 182, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiasat, M.S.; Zamani, H.A.; Aghdam, M.M. On the transient response of viscoelastic beams and plates on viscoelastic medium. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2014, 83, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazwari, M.A.; Zenkour, A.M. A quasi-3D refined theory for the vibration of functionally graded plates resting on Visco-Winkler-Pasternak foundations. Mathematics 2022, 10, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Yang, G.; Pu, Y.; Ma, P.; Li, K. Free Vibration Characteristics of Functionally Graded Material (FGM) Beams on Three-Parameter Viscoelastic Foundation. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrulj, J.; Dzaferovic, E.; Obucina, M.; Kuzman, M.K. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of Polymer Viscoelastic Materials Obtained by 3D Printing. Polymers 2021, 13, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lv, S.; Xie, N.; Meng, H.; Lei, W.; Pu, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, G.; Peng, X. Comparative Study on the Dynamic Response of Asphalt Pavement Structures: Analysis Using the Classic Kelvin, Maxwell, and Three-Parameter Solid Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanes, R.M.; Greco, M.; Almeida, V.D. Viscoelastic Soil–Structure Interaction Procedure for Building on Footing Foundations Considering Consolidation Settlements. Buildings 2023, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M.; Brooks, J.J. Concrete Technology; Longman Scientific & Technical England: London, UK, 1987; Volume 438. [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto, S.; Dick, W.D.; Hunt, B.; Szymanski, W.W.; McMurry, P.H.; Roberts, D.L.; Pui, D.Y.H. Characterization of nanosized silica size standards. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiestel, T.; Brunner, H.; Tovar, G.E. Controlled surface functionalization of silica nanospheres by covalent conjugation reactions and preparation of high density streptavidin nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2004, 4, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2011; p. 846. ISBN 9780273755807. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Subhani, T.; Husain, S.W. Synthesis and characterization of silica nanoparticles from clay. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2016, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D., Jr. Materials Science and Engineering an Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781119405436. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R.R., Jr.; Kurdila, A.J. Fundamentals of Structural Dynamics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 0471430447. [Google Scholar]

- Thai, H.-T.; Choi, D.-H. A refined plate theory for functionally graded plates resting on elastic foundation. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2011, 71, 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani Baferani, A.; Saidi, A.R.; Ehteshami, H. Accurate solution for free vibration analysis of functionally graded thick rectangular plates resting on elastic foundation. Compos. Struct. 2011, 93, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, J. Shear correction factors for orthotropic laminates under static load. J. Appl. Mech. Mar. 1973, 40, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, G. Über das Gleichgewicht und die Bewegung einer elastischen Scheibe. J. Die Reine Angew. Math. (Crelles J.) 1850, 1850, 51–88. [Google Scholar]

| Concrete Type | NS/MS Content (wt%) | Conclusions | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| -Moderate, high strength concrete | / | -Incorporation of MS and/or NS significantly increases compressive strength. -Elastic modulus and splitting tensile strength are only marginally affected. -Bond strength and slip energy are improved for plain steel rebar, while limited or negative effects are observed for ribbed rebar. | [16] |

| -Ordinary Concrete | / | -Increasing the quantity of NS can enhance the compressive strength of concrete. | [17] |

| -Recycled concrete | 0, 3 and 6% | -A higher content of NS tends to enhance the relative residual splitting tensile strength of concrete. | [18] |

| -Geopolymer concrete (GPC) | 2% | -Steel fiber did not lead to a significant improvement in compressive strength unless paired with NS. | [19] |

| -Recycled aggregate geopolymer concrete | 1, 2 and 3% | -Mechanical and durability properties of GPC were both improved through the substitution of 1% NS. | [20] |

| -Fiber-reinforced concrete | 1, 2 and 3% | -Concrete containing 10% SiO2 Fumes, and 1% steel fibers exhibits favorable mechanical properties. | [21] |

| -High-strength concrete | 1 and 2% | -Replacing a portion of the cement with 2% NS resulted in enhanced overall strength of the concrete. | [22] |

| -High-performance concrete | 0.5∼3% | -Increasing NS content leads in improved structural behavior. -2% addition of nano-SiO2 was the optimal dosage. | [23,24,25] |

| -High-volume fly ash concrete | 2 and 4% | ||

| -High-strength light weight concrete | 3% | -In chemical aggressive environments, NS enhances the strength of concrete. | [26] |

| -Coal and fly ash concrete | 1∼5% | -Incorporating NS can significantly enhance the mechanical performance of concrete, as well as its resistance to freeze–thaw cycles and chloride ion penetration. | [27] |

| -Self-compacting concrete | 0∼6% | -Enhancing concrete’s mechanical performance against static loads can be achieved through the incorporation of fibers and NS. | [28] |

| Concrete Type | NS Content (wt%) | Conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| -Ultra-high performance concrete | 3% | -In presence of fiber reinforcement, nano-SiO2 additions appear to have an insignificant influence on the dynamic strengths of the material. However, the strength of the material can be increased with increasing volume dosage of nanomaterials. | [29] |

| -High volume fly ash concrete | 0.12% | -The dynamic compressive strengths of high volume fly ash concrete were higher at 400 and 700 °C. | [30] |

| -High-volume fly ash concrete with polypropylene fibers | 0.12% | -The concrete exhibited improved performance even at early ages regarding dynamic compressive strength, critical strain, damage resistance, and toughness, attributed to the enhanced activity of NS during the heating process. | [31] |

| -Fibrous ultra-high performance concrete | 1% | -Incorporation of 20% silica fume in addition to 2% of steel fibers or 1% of NS resulted in improvement in fiber-matrix bond and dynamic properties of UHPC. | [32] |

| Elastic Properties | Refs. | Concrete Matrix | NS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s modulus (GPa) | [69,70] | ||

| Poisson’s ration | [69,71] | ||

| Density (Kg/m3) | [72,73] | ||

| Shear modulus (GPa) | * [74] | ||

| Bulk modulus (GPa) | * [74] |

| Volume Percentage of NS Reinforcement in a Concrete Matrix | Analytical Homogenization Approaches | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | Eshelby’s approach | 22.22 | 5.56 | 16.67 |

| Voigt approach | 22.22 | 5.56 | 16.67 | |

| 22.22 | 5.56 | 16.67 | ||

| 10% | Eshelby’s approach | 24.89 | 6.32 | 19.18 |

| Voigt approach | 25.37 | 6.34 | 19.03 | |

| 25.41 | 6.75 | 18.65 | ||

| 20% | Eshelby’s approach | 27.94 | 7.26 | 21.89 |

| Voigt approach | 28.70 | 7.18 | 19.03 | |

| 29.02 | 8.18 | 20.83 | ||

| 30% | Eshelby’s approach | 31.47 | 8.41 | 24.80 |

| Voigt approach | 32.26 | 8.07 | 24.20 | |

| 33.14 | 9.90 | 23.24 | ||

| Theory | Shape Function f(z) | Power Law Index ‘P’ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Refined Quasi-3D theory (Present) | 0.1085 | 0.0924 | 0.0836 | 0.0761 | 0.0715 | |

| Refined plate theory (RPT) [76] | 0.1135 | 0.0964 | 0.0869 | 0.0788 | 0.0740 | |

| Trigonometric shear deformation theory (TrSDT) [77] | 0.1134 | 0.0975 | 0.0891 | 0.0819 | 0.0767 | |

| First order shear deformation theory (FSDT) [78] | 0.1133 | 0.0963 | 0.0868 | 0.0789 | 0.0744 | |

| Classical plate theory (CPT) [79] | 0.1164 | 0.0986 | 0.0888 | 0.0807 | 0.0765 | |

| Theory | Volume Percentage of NS Reinforcement ‘Vr’ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| Refined Quasi-3D theory (Present) | 0.6719 | 0.6947 | 0.7178 | 0.7413 | 0.7653 | 0.7897 | 0.8147 |

| Refined plate theory (RPT) | 0.6867 | 0.7101 | 0.7339 | 0.7581 | 0.7830 | 0.8084 | 0.8346 |

| Trigonometric shear deformation theory (TrSDT) | 0.6867 | 0.7101 | 0.7339 | 0.7581 | 0.7830 | 0.8084 | 0.8346 |

| First order shear deformation theory (FSDT) * | 0.6867 | 0.7100 | 0.7338 | 0.7581 | 0.7830 | 0.8084 | 0.8346 |

| Classical plate theory (CPT) | 0.6986 | 0.7223 | 0.7465 | 0.7711 | 0.7963 | 0.8222 | 0.8488 |

| Volume Percentage of NS Reinforcement ‘Vr’ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | ||

| 10 | 0 | 0.6719 | 0.6947 | 0.7178 | 0.7413 | 0.7653 | 0.7897 | 0.8147 |

| 5 | 0.6659 | 0.6889 | 0.7122 | 0.7359 | 0.7600 | 0.7845 | 0.8097 | |

| 10 | 0.6033 | 0.6285 | 0.6538 | 0.6794 | 0.7054 | 0.7317 | 0.7585 | |

| 20 | 10 | 0.5335 | 0.5616 | 0.5897 | 0.6179 | 0.6462 | 0.6748 | 0.7036 |

| 20 | 0.5259 | 0.5544 | 0.5828 | 0.6113 | 0.6399 | 0.6687 | 0.6978 | |

| 30 | 30 | 0.3433 | 0.3851 | 0.4247 | 0.4627 | 0.4996 | 0.5357 | 0.5715 |

| 50 | 30 | 0.2211 | 0.1368 | 0.1141 | 0.2155 | 0.2857 | 0.3447 | 0.3976 |

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 3.9539 | 4.9843 | 5.4385 | 5.8839 | 6.0557 | 6.1463 | 6.2401 |

| 20 | 3.9409 | 4.9776 | 5.4343 | 5.8818 | 6.0543 | 6.1452 | 6.2394 | |

| 50 | 3.9013 | 4.9573 | 5.4216 | 5.8754 | 6.0500 | 6.1421 | 6.2373 | |

| 10 | 10 | 3.6821 | 4.8478 | 5.3535 | 5.8414 | 6.0276 | 6.1253 | 6.2262 |

| 20 | 3.6674 | 4.8407 | 5.3491 | 5.8392 | 6.0262 | 6.1243 | 6.2255 | |

| 50 | 3.6228 | 4.8191 | 5.3358 | 5.8327 | 6.0219 | 6.1210 | 6.2233 | |

| 20 | 10 | 3.3721 | 4.7017 | 5.2647 | 5.7980 | 5.9991 | 6.1041 | 6.2122 |

| 20 | 3.3551 | 4.6941 | 5.2601 | 5.7958 | 5.9976 | 6.1031 | 6.2115 | |

| 50 | 3.3031 | 4.6708 | 5.2463 | 5.7891 | 5.9933 | 6.0998 | 6.2093 | |

| 30 | 10 | 3.0037 | 4.5439 | 5.1719 | 5.7537 | 5.9702 | 6.0827 | 6.1981 |

| 20 | 2.9828 | 4.5356 | 5.1671 | 5.7515 | 5.9687 | 6.0817 | 6.1974 | |

| 50 | 2.9186 | 4.5103 | 5.1526 | 5.7446 | 5.9643 | 6.0784 | 6.1952 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chatbi, M.; Lozančić, S.; Harrat, Z.R.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M. Computational Models for the Vibration and Modal Analysis of Silica Nanoparticle-Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Elastic and Viscoelastic Foundation Effects. Modelling 2026, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010008

Chatbi M, Lozančić S, Harrat ZR, Hadzima-Nyarko M. Computational Models for the Vibration and Modal Analysis of Silica Nanoparticle-Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Elastic and Viscoelastic Foundation Effects. Modelling. 2026; 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatbi, Mohammed, Silva Lozančić, Zouaoui R. Harrat, and Marijana Hadzima-Nyarko. 2026. "Computational Models for the Vibration and Modal Analysis of Silica Nanoparticle-Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Elastic and Viscoelastic Foundation Effects" Modelling 7, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010008

APA StyleChatbi, M., Lozančić, S., Harrat, Z. R., & Hadzima-Nyarko, M. (2026). Computational Models for the Vibration and Modal Analysis of Silica Nanoparticle-Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Elastic and Viscoelastic Foundation Effects. Modelling, 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010008