GPU-Accelerated FLIP Fluid Simulation Based on Spatial Hashing Index and Thread Block-Level Cooperation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. FLIP Algorithm in Fluid Simulation

2.1. Related Work

2.2. Algorithm Steps of FLIP

| Algorithm 1: FLIP Simulation Procedure on the GPU |

| For each timestep do For each particle p do End Perform spatial indexing; Section 3.2.1 For each grid cell in parallel do ; Section 3.2.2 End For each grid cell g at location (x, y, z) in parallel do Apply external force: ; End Apply Boundary conditions; // Grid solution and velocity field update Solve Poisson pressure equation to obtain pressure ; For each grid cell g in parallel do Compute the new velocity field at the cell: ; End For each particle p do ; End End |

3. GPU-Based Parallel Computing

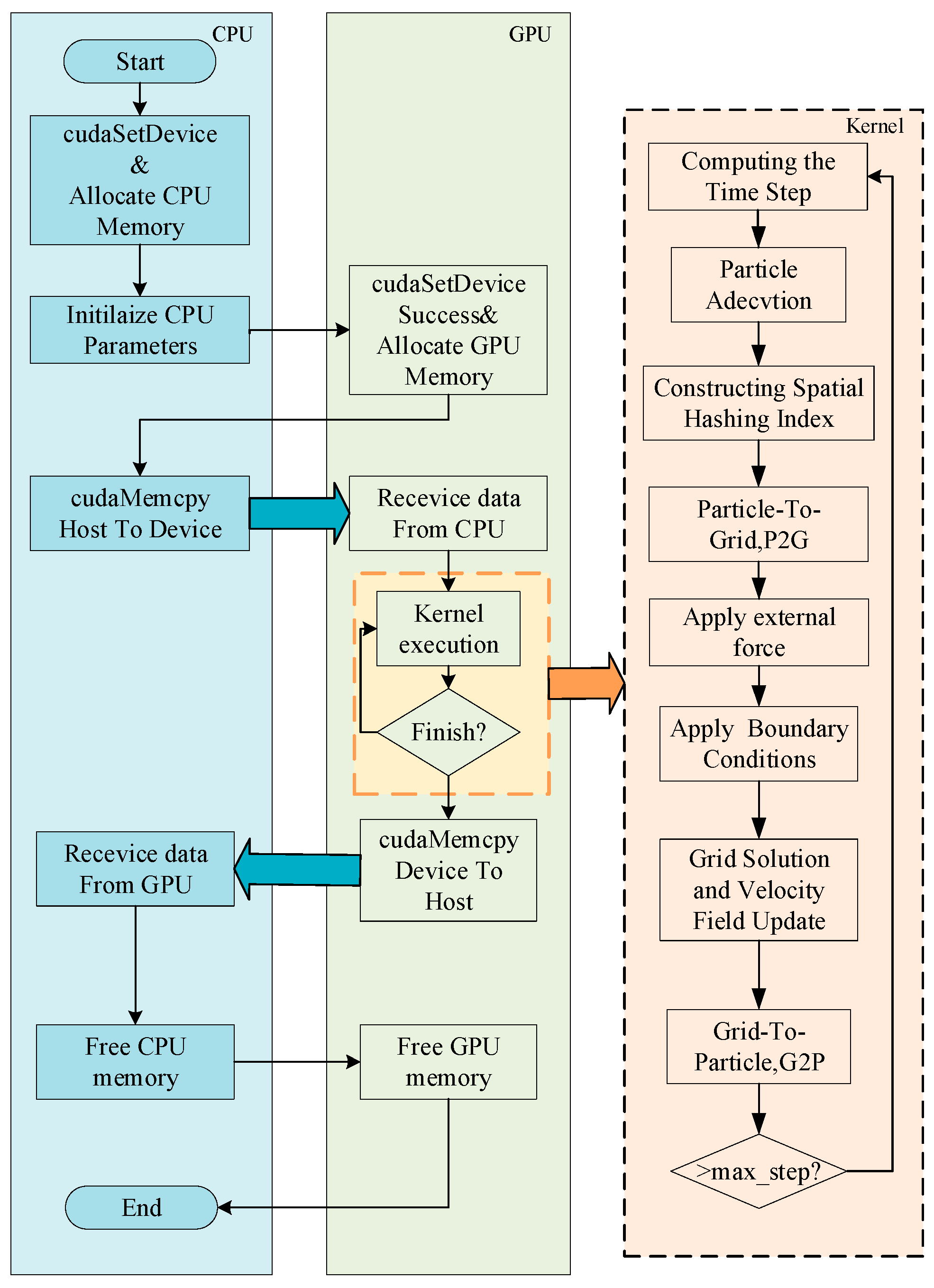

3.1. FLIP Parallel Algorithm Framework on GPU Architecture

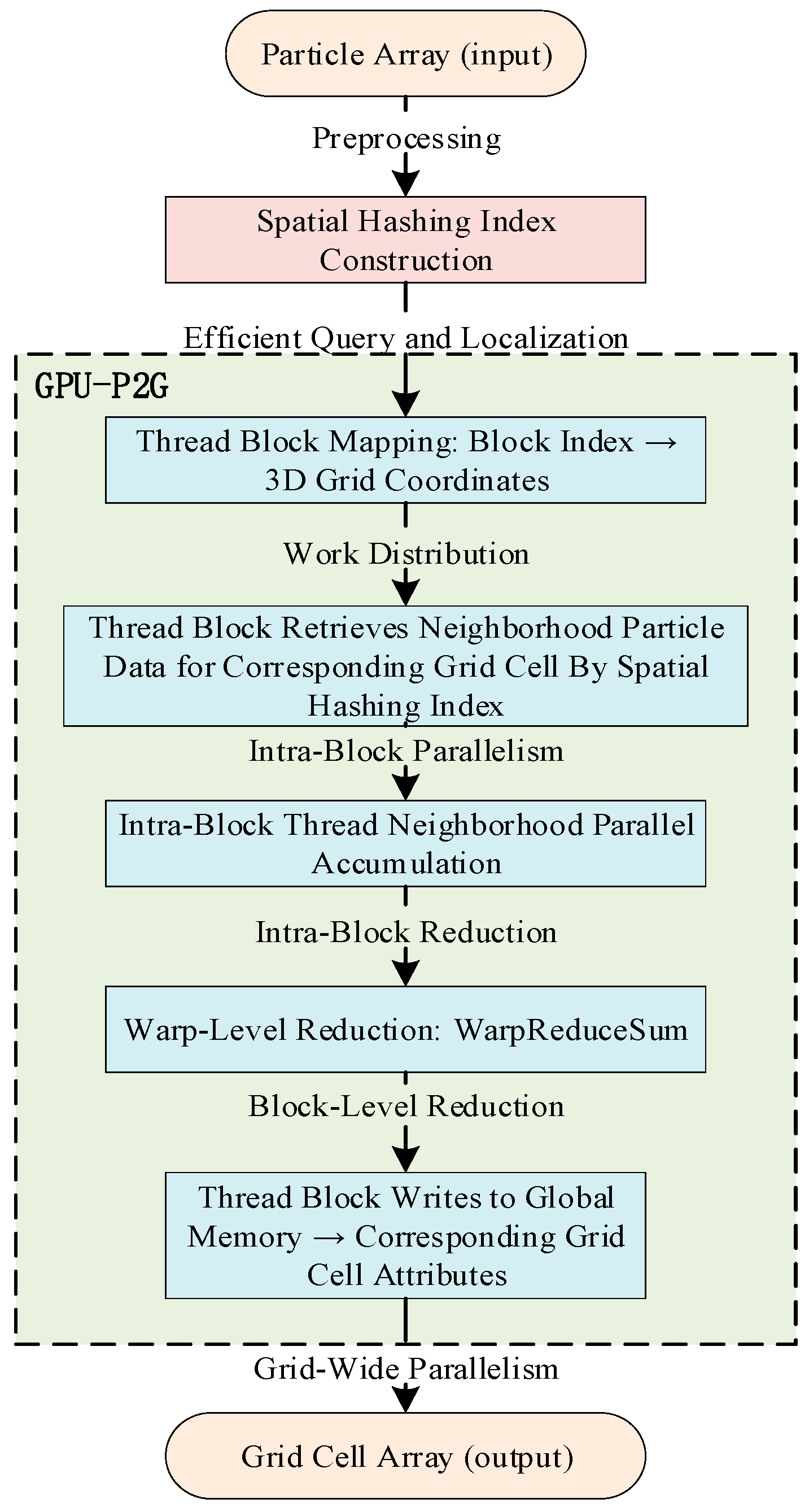

3.2. Parallel Optimization Strategy for Particle-to-Grid Mapping (P2G)

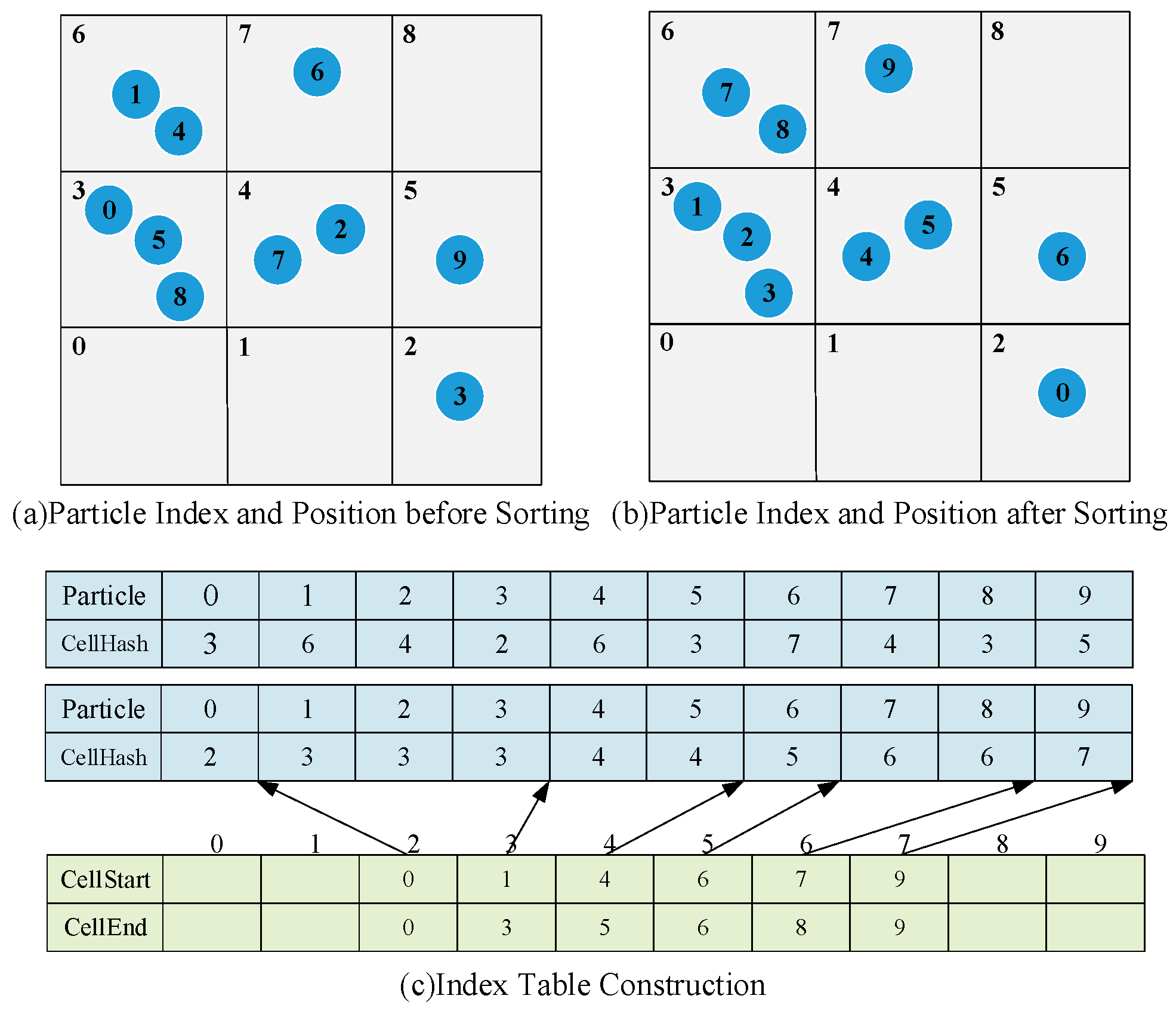

3.2.1. Spatial Hashing Index

- Cell Hashing: For each particle at position , we compute the index of the grid cell it resides in: , , . We then compute a unique hash key for this cell using a linearizing function: for a grid of size . This function ensures no hash collisions, as it provides a one-to-one mapping between 3D cell coordinates and a 1D key. We store this hash key, , in an array, , where each element corresponds to a particle and records the hash key of the grid cell that contains the particle.

- Sorting: We sort the array of particle indices based on their using the function from the CUDA Thrust library. This physically reorders the particle data array so that all particles belonging to the same grid cell become contiguous in memory.

- Building Cell Start/End Indices: Create two index arrays, and , which represent the starting particle index and ending particle index of adjacent particles in each cell, respectively. After sorting, we launch a kernel with one thread per particle to identify the boundaries where the changes. We fill two index arrays, and . For a given cell with , points to the first index in the sorted particle array that belongs to cell H, and points to the last index. This allows constant-time lookup of all particles within any specific grid cell.

3.2.2. Thread Block-Level Cooperation Optimization Strategy

| Algorithm 2: Thread-Block Cooperative P2G Kernel |

| Input: Sorted particle data, , Output: Updated grid velocity . // Thread Block Mapping // Equations (6) and (7) Allocate and Initialize , in shared memory // is neighboring cell’s counts // Intra-Block Thread Neighborhood Parallel Accumulation For each grid cell of 27 neighboring cells in parallel do // compute neighboring grid cell hash index: If : For particle index ; ; do Load particle at index End End End __syncthreads() // Ensure all particle processing is complete // Warp-level intra-block reduction (using warp shuffle) // Block-Level Reduction If then End __syncthreads() // Write back results (no atomic operations) Write to update grid velocity |

4. Experimental Results and Analysis of GPU Parallel Acceleration

4.1. Operating Environment

4.2. Performance Analysis

4.2.1. Spatial Hashing Index Construction Overhead Analysis

4.2.2. GPU-P2G Runtime Comparison

4.2.3. Thread Block-Level Mapping Optimization Strategy: Runtime Comparison

4.2.4. Overall Computational Efficiency Comparison

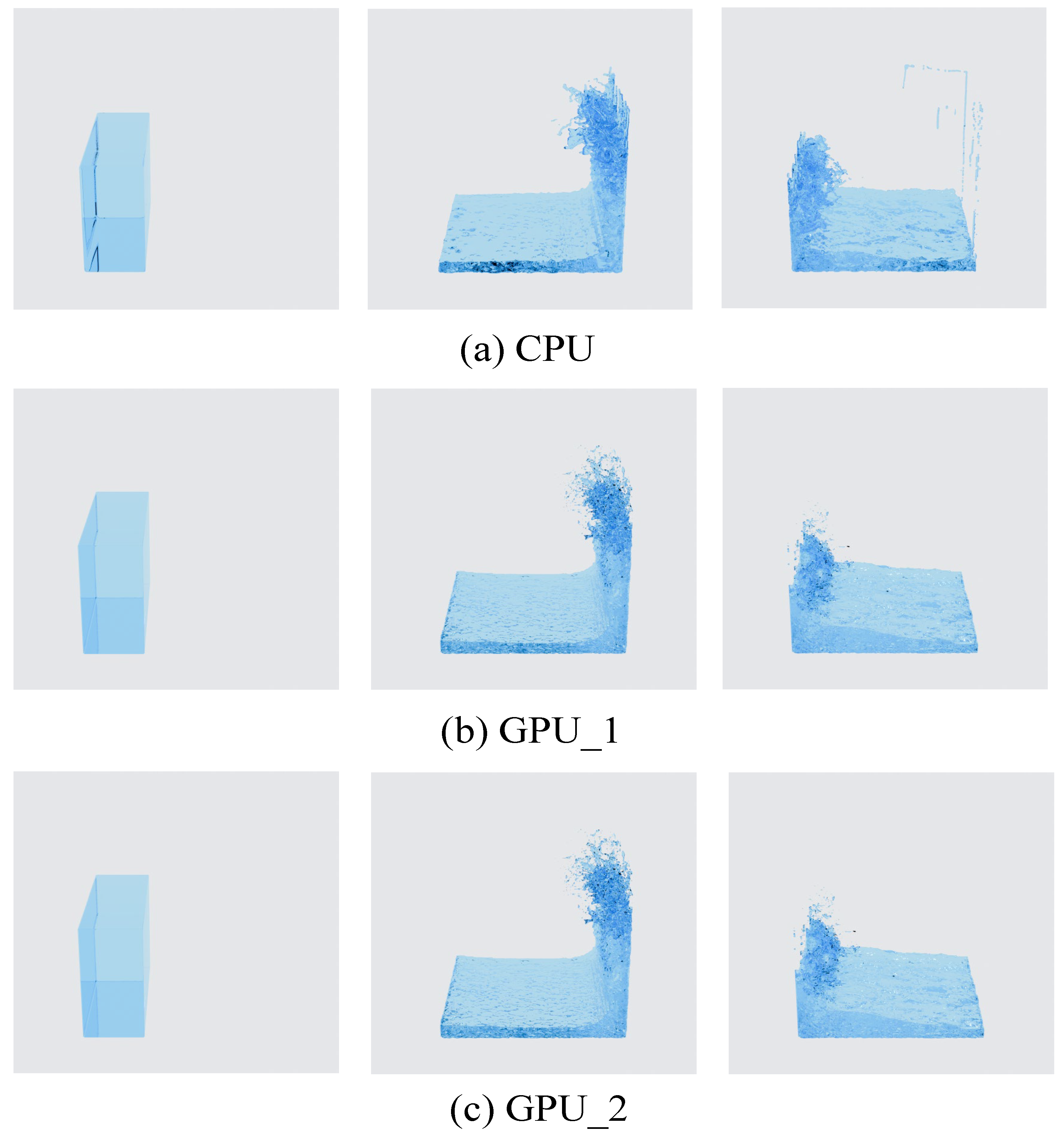

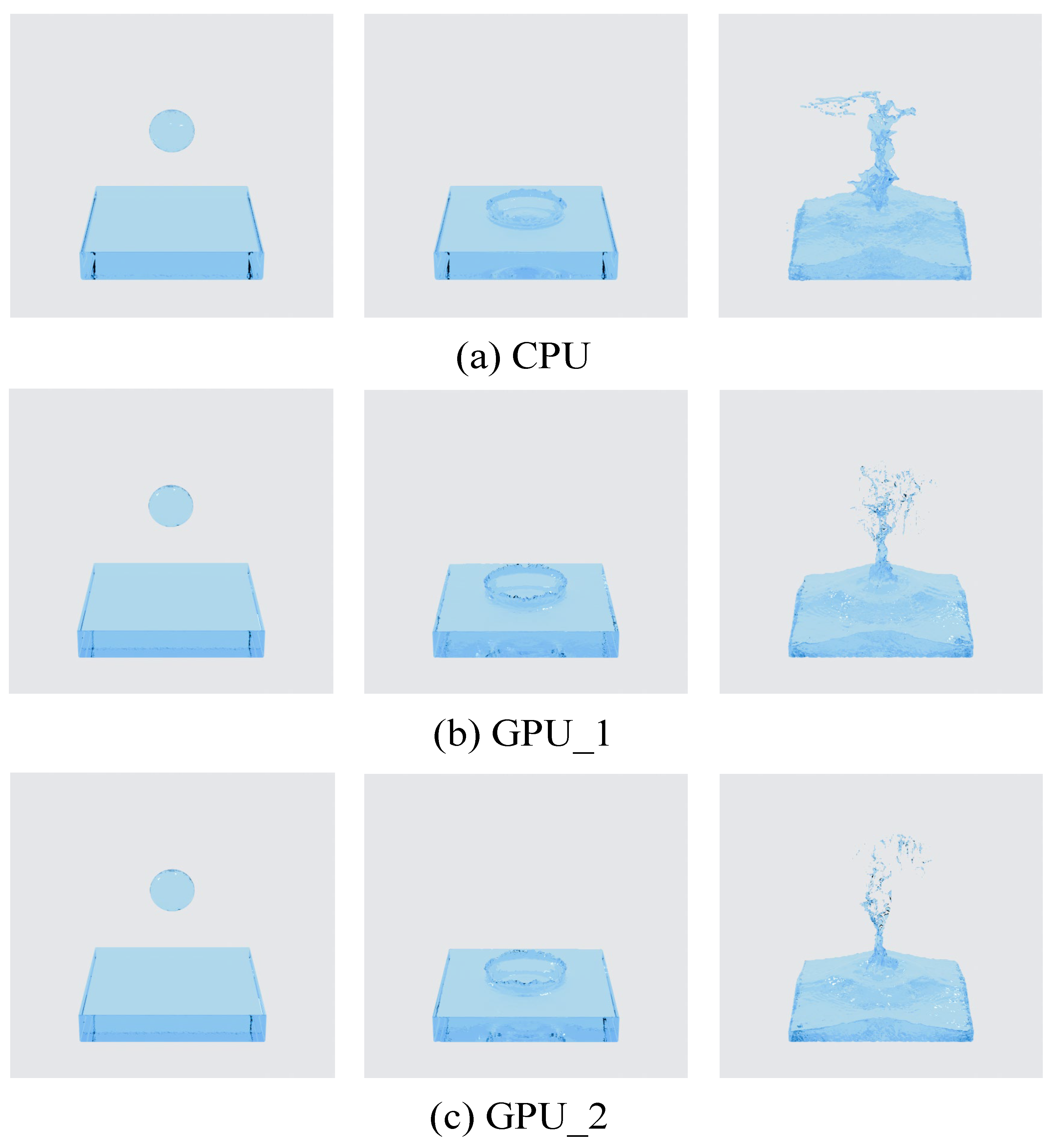

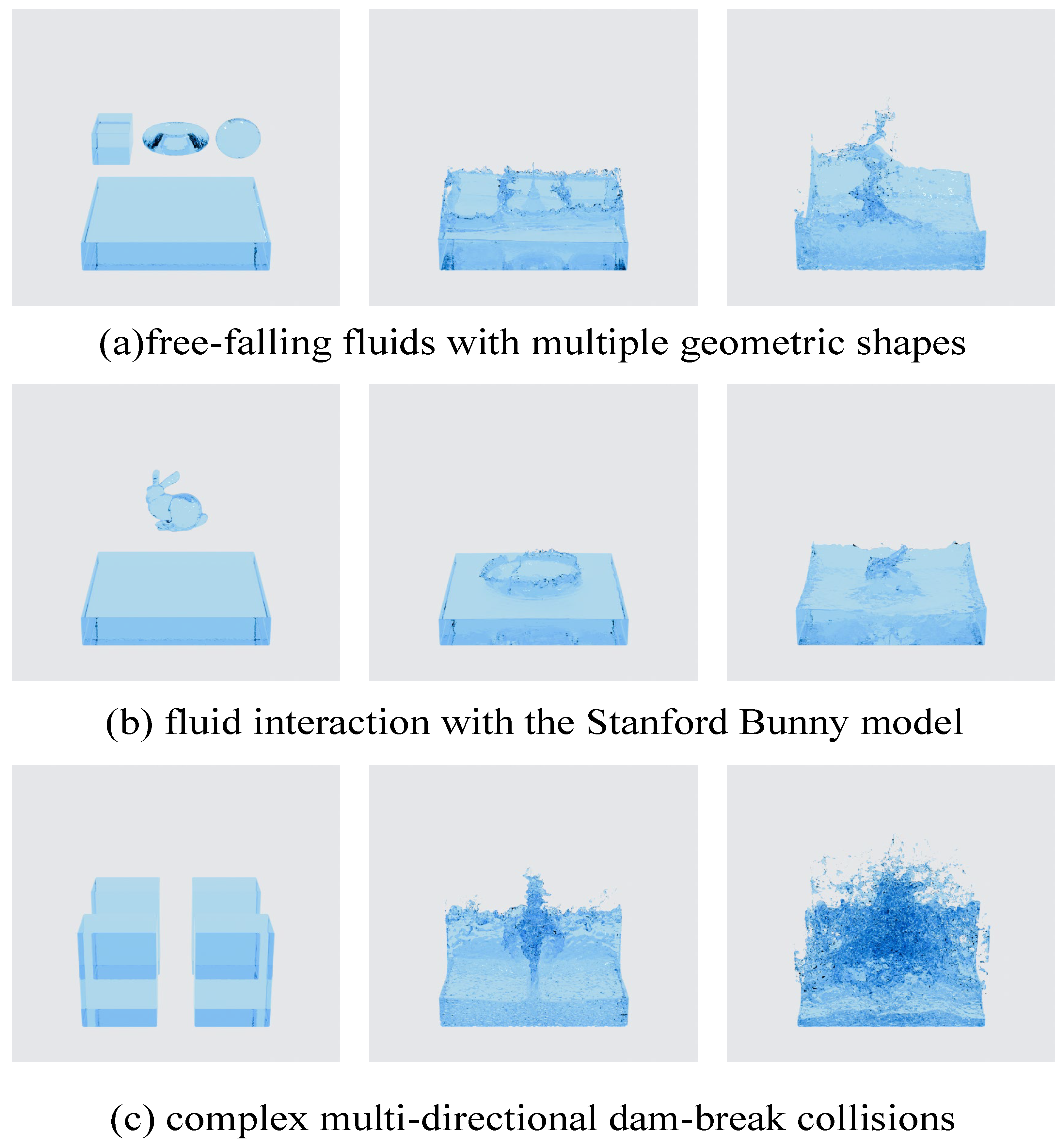

4.3. Simulation Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stam, J. Stable fluids. ACM Trans. Graph. 2001, 1999, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Brackbill, J.U.; Kothe, D.B.; Ruppel, H.M. Flip: A low-dissipation, particle-in-cell method for fluid flow. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1988, 48, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Bridson, R. Animating sand as a fluid. ACM Trans. Graph. 2005, 24, 965972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D.B.; Hwu, W.-M.W. Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands—On Approach; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, M.; Qureshi, M.K.; Balasubramonian, R. Memory bandwidth characterization of graphics processing units. In Proceedings of the 2010 37th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), Saint-Malo, France, 19–23 June 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Nickolls, J.; Buck, I.; Garland, M.; Skadron, K. Scalable parallel programming with CUDA. Queue 2008, 6, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.J. Fast fluid dynamics simulation on the GPU. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH 2005 Courses, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 31 July–4 August 2005; ACM: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Kim, B.; Ito, D.; Wang, H. Wetbrush: GPU-based 3d painting simulation at the bristle level. ACM Trans. Graph. 2015, 34, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F. Research and Implementation of a Parallel SPH Algorithm Based on Many-Core Architecture. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2013. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.Q.; Zheng, X.; Duan, W.Y. Simulation of viscous flow field using an improved SPH method with GPU acceleration. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2015, 36, 1011–1018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.G.; Huang, X.; Zheng, X.; Duan, W.Y. Research on the application of GPU in the SPH method to simulate the dam failure problem. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2014, 35, 661–666. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Parreiras, E.A.; Vieira, M.B.; Machado, A.G.; Renhe, M.C.; Giraldi, G.A. A particle-in-cell method for anisotropic fluid simulation. Comput. Graph. 2022, 102, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.M.; Yang, C.H.; Kang, Z.; Zhou, L. Application of an improved GPU acceleration strategy in smoothed particle hydrodynamics. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. 2023, 57, 981–987. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; O’brien, J.F.; Fedkiw, R. Fast fluid simulations with sparse volumes on the GPU. Comput. Graph. Forum 2018, 37, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.J.; Shi, F.L. A GPU-CUDA parallel virtual grid finite difference solver. J. Hydrodyn. 2023, 38, 523–527. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Jiang, M.; Liu, Z. Accelerating fully resolved simulation of particle-laden flows on heterogeneous computer architectures. Particuology 2023, 81, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, R.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.X. An integrated framework for accelerating reactive flow simulation using GPU and machine learning models. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. CUDA C Programming Guide [EB/OL]. (2013-06) [2024-07-01]. Available online: https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/cuda-c-programming-guide/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Boyd, L.; Bridson, R. Multi FLIP for energetic two-phase fluid simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. 2012, 31, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.P.; Li, S.; Xia, Q.; Hong, Q.; Aimin, H. A novel integrated analysis-and-simulation approach for detail enhancement in FLIP fluid interaction. In Proceedings of the 21stACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Beijing, China, 13 November 2015; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ferstl, F.; Ando, R.; Wojtan, C.; Westermann, R.; Thuerey, N. Narrow band FLIP for liquid simulations. Comput. Graph. Forum 2016, 35, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, S.; Shu, C.W. Total variation diminishing Runge-Kutta schemes. Math. Comput. 1998, 67, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Jin, A.F. Application of GPU-based neighbour search method in SPH algorithm for sand-laden wind flow. Comput. Appl. Softw. 2025, 42, 221–226. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, D.; Rezavand, M.; Rauch, W. Neighbour lists for smoothed particle hydrodynamics on GPUs. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2018, 225, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Wang, Y.L.; Jiao, G.S.; Qian, H.J.; Lu, Z.Y. Accelerating electrostatic interaction calculations with graphical processing units based on new developments of Ewald method using non-uniform fast Fourier transform. J. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Device | Model | Number of Cores | Memory/Graphics Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | AMD Ryzen 77,840 H with Radeon 780 M Graphics | 8 | 16 |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Laptop GPU | 3072 | 8 |

| Particle | Grid | Build Hash Array | Sort Particles | Create Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 M | 1283 | 0.73 | 5.12 | 0.20 |

| 7 M | 1603 | 1.34 | 10.37 | 0.36 |

| 12 M | 1923 | 2.23 | 16.15 | 0.59 |

| 20 M | 2243 | 3.45 | 24.82 | 0.89 |

| Particle | Grid | Particle Thread Scattering Strategy/ms | Global Thread Strategy/ms | Improv. | Thread Block-Level Cooperation Optimization Strategy/ms | Improv. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 M | 1283 | 23.55 | 18.30 | 22% | 15.23 | 35% |

| 7 M | 1603 | 46.25 | 37.39 | 19% | 29.05 | 37% |

| 12 M | 1923 | 93.93 | 68.33 | 27% | 49.46 | 47% |

| 20 M | 2243 | 171.28 | 111.74 | 35% | 78.28 | 54% |

| Particle | Grid | Global Thread Strategy/ms | Thread Block-Level Cooperation Optimization Strategy/ms | Improv. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 M | 1283 | 18.30 | 15.23 | 17% |

| 7 M | 1603 | 37.39 | 29.05 | 22% |

| 12 M | 1923 | 68.33 | 49.46 | 28% |

| 20 M | 2243 | 111.74 | 78.28 | 30% |

| Grid: 1923 Particle: 12 M | GPU_1/ms | GPU_2/ms | |

| Advection | 11.09 | 7.13 | |

| P2G | 93.93 | 49.88 | |

| Pressure Solve | 101.61 | 101.44 | |

| G2P | 8.52 | 6.4 | |

| Other | 3.19 | 1.17 | |

| Total Time | 218.32 | 166.02 |

| Grid | CPU/ms | GPU_1/ms | Speedup Ratio_1 | GPU_2/ms | Speedup Ratio_2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1283 | 1887.10 | 45.77 | 41.2 | 35.60 | 53.0 |

| 1603 | 3842.53 | 115.31 | 33.3 | 92.60 | 41.5 |

| 1923 | 7147.20 | 218.32 | 32.7 | 166.02 | 43.1 |

| 2243 | 12,364.20 | 372.02 | 33.2 | 261.03 | 47.4 |

| Cell | CPU/ms | GPU_1/ms | Speedup Ratio_1 | GPU_2/ms | Speedup Ratio_2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1283 | 1733.55 | 40.17 | 43.2 | 31.82 | 54.5 |

| 1603 | 3846.51 | 103.93 | 37.0 | 85.91 | 44.8 |

| 1923 | 7308.04 | 185.74 | 39.4 | 153.60 | 47.6 |

| 2243 | 12,820.96 | 297.08 | 43.2 | 241.65 | 53.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, C.; Luo, H. GPU-Accelerated FLIP Fluid Simulation Based on Spatial Hashing Index and Thread Block-Level Cooperation. Modelling 2026, 7, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010027

Zou C, Luo H. GPU-Accelerated FLIP Fluid Simulation Based on Spatial Hashing Index and Thread Block-Level Cooperation. Modelling. 2026; 7(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Changjun, and Hui Luo. 2026. "GPU-Accelerated FLIP Fluid Simulation Based on Spatial Hashing Index and Thread Block-Level Cooperation" Modelling 7, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010027

APA StyleZou, C., & Luo, H. (2026). GPU-Accelerated FLIP Fluid Simulation Based on Spatial Hashing Index and Thread Block-Level Cooperation. Modelling, 7(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling7010027