Examination of Long-Term Diseases, Conditions, Self-Control, and Self-Management in Kidney Transplant Recipients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Participants

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection Tools

2.4. Personal Information Form

2.5. Post-Kidney Transplant Diseases and Conditions Assessment Form

2.6. Self-Control and Self-Management Scale

2.7. Charlson Comorbidity Index

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hariharan, S.; Israni, A.K.; Danovitch, G. Long-term survival after kidney transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugi, M.D.; Joshi, G.; Maddu, K.K.; Dahiya, N.; Menias, C.O. Imaging of renal transplant complications throughout the life of the allograft: Comprehensive multimodality review. Radiographics 2019, 39, 1327–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poggio, E.D.; Augustine, J.J.; Arrigain, S.; Brennan, D.C.; Schold, J.D. Long-term kidney transplant graft survival—Making progress when most needed. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2824–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülbüloğlu, S.; Güneş, H.; Saritaş, S. The Effect of Long-Term Immunosuppressive Therapy on Gastrointestinal Symptoms after Kidney Transplantation. J. Transplant. Immunol. 2022, 70, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajanding, R. Immunosuppression following organ transplantation. Part 1: Mechanisms and immunosuppressive agents. Br. J. Nurs. 2018, 27, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, F.R.; Moreno, A.; Ridao, N.; Calvo, N.; Pérez-Flores, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez, A.; Marques, M.; Barrientos. Kidney transplantation complications related to psychiatric or neurological disorders. Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 2430–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoskes, A.; Wilson, R. Neurologic complications of kidney transplantation. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2019, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. National Data. 2019. Available online: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Merion, R.M.; Ashby, V.B.; Wolfe, R.A.; Distant, D.A.; Hulbert-Shearon, T.E.; Metzger, R.A.; Ojo, A.O.; Port, F.K. Deceased-donor characteristics and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation. JAMA 2005, 294, 2726–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, G.; Tugmen, C.; Sert, İ. Organ Transplantation in the Turkey and the World. Tepecik Educ. Res. Hosp. J. 2019, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. Kan, Organ ve Doku Nakli Hizmetleri. [Blood, Organ and Tissue Transplant Services]. 2019. Available online: https://organkds.saglik.gov.tr/dss/PUBLIC/PublicDefault2.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) for Clinicians. 2019. Available online: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/professionals/by-topic/guidance/kidney-donor-profile-index-kdpi-guide-for-clinicians (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A.; Modecki, K.L.; Webb, H.J.; Gardner, A.A.; Hawes, T.; Rapee, R.M. The self-perception of flexible coping with stress: A new measure and relations with emotional adjustment. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5, 1537908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbuloglu, S.; Harmanci, P.; Aslan, F.E. Investigation of perceived stress and psychological well-being in liver recipients having immunosuppressive therapy. iLiver 2023, 2, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenito-Moyet, L.J. Nursing Diagnosis: Application to Clinical Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ordin, Y.S.; Karayurt, Ö.; Çilengiroğlu, Ö.V. Validation and adaptation of the Modified Transplant Symptom Occurrence and Symptom Distress Scale-59 Items Revised into Turkish. Prog. Transplant. 2013, 23, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajanding, R. Immunosuppression following organ transplantation. Part 2: Complications and their management. Br. J. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordin, Y.S. Karaciğer Transplantasyonu Sonrası Destek Grup Girişiminin Hastaların Bilgi, Semptom Ve Yaşam Kalitesi Düzeyine Etkisinin İncelenmesi. Ph.D. Thesis, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi, Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü, İzmir, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mezo, P.G. The Self-Control and Self-Management Scale (SCMS): Development of an adaptive selfregulatory coping skills instrument. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2009, 31, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercoşkun, M.H. Adaptation of Self-Control and Self-Management Scale (SCMS) into Turkish culture: A study on reliability and validity. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2016, 16, 1125–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Ming, H. Effects of hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and renal transplantation on the quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2020, 66, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, C.; Canaud, G.; Martinez, F. Factors influencing long-term outcome after kidney transplantation. Transplant. Int. 2014, 27, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, F.; Aronen, P.; Koskinen, P.K.; Malmström, R.K.; Finne, P.; Honkanen, E.O.; Sintonen, H.; Roine, R.P. Health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation: Who benefits the most? Transplant. Int. 2014, 27, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.S.; Shan, L.L.; Saxena, A.; Morris, D.L. Liver transplantation: A systematic review of long-term quality of life. Liver Int. 2014, 34, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyahi, N.; Ateş, K.; Süleymanlar, G. Current status of renal replacement therapy in Turkey: A summary of the 2019 Turkish Society of Nephrology registry report. Turk. J. Nephrol. 2021, 30, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, B. The analysis of immunosuppressant therapy adherence, depression, anxiety, and stress in kidney transplant recipients in the post-transplantation period. Transpl. Immunol. 2022, 75, 101686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, J.; Smith, A.C. Cardiovascular risk factors following renal transplant. World J. Transplant. 2015, 5, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoumpos, S.; Jardine, A.G.; Mark, P.B. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after kidney transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2015, 28, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepperman, E.; Ramzy, D.; Prodger, J.; Sheshgiri, R.; Badiwala, M.; Ross, H.; Rao, V. Surgical biology for the clinician: Vascular effects of immunosuppression. Can. J. Surg. 2010, 53, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Çınar, F.; Bulbuloglu, S. The Analysis of Liver Transplant Recipients’ Adherence to Immunosuppressant Therapy, Self-Control, and Self-Management in the Post-Transplantation Period. iLiver J. 2023, 2, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Characteristics | n | % | SCMSS Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Between 18 and 30 years (1) | 30 | 23.1 | 70.33 ± 12.69 |

| Between 31 and 45 years (2) | 52 | 40 | 74.75 ± 13.73 |

| Between 46 and 64 years (3) | 40 | 30.8 | 69.17 ± 12.77 |

| 65 years and above (4) | 8 | 6.2 | 69.3 ± 10.18 |

| Test and value | F = 0.553, p = 0.017 * | ||

| Post Hoc | 2 > 1, 3, 4 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 59 | 45.4 | 69.5 ± 13.25 |

| Male | 71 | 54.6 | 70.11 ± 10.48 |

| Test and value | t = 0.084, p = 0.772 | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 57 | 43.8 | 69.75 ± 11.43 |

| Married | 73 | 56.2 | 69.94 ± 12.3 |

| Test and value | t = 0.009, p = 0.926 | ||

| Educational Level | |||

| Primary school | 40 | 30.8 | 68.15 ± 13.04 |

| High school | 45 | 34.6 | 70.57 ± 10.96 |

| University and above | 45 | 34.6 | 69.57 ± 11.33 |

| Test and value | F = 0.441, p = 0.779 | ||

| Income level | |||

| Higher income (1) | 19 | 14.6 | 70.31 ± 8.66 |

| Middle income (2) | 66 | 50.8 | 71.9 ± 11.36 |

| Low income (3) | 45 | 34.6 | 66.6 ± 12.96 |

| Test and value | F = 2.813, p = 0.014 * | ||

| Post Hoc | 1, 2 > 3 | ||

| Employment status | |||

| Retired | 34 | 26.2 | 69.55 ± 11.13 |

| Unemployed | 39 | 30 | 70.43 ± 13 |

| Employed | 57 | 43.8 | 69.59 ± 11.45 |

| Test and value | F = 0.071, p = 0.932 | ||

| Organ Donor | |||

| Cadaveric | 24 | 18.5 | 69.27 ± 11.56 |

| Alive | 106 | 81.5 | 71.33 ± 12.64 |

| Test and value | t = 0.324, p = 0.252 | ||

| Graft rejection | |||

| Yes | 14 | 10.8 | 67.33 ± 9.99 |

| No | 116 | 90.2 | 72.41 ± 10.24 |

| Test and Value | t = 0.023, p = 0.023 * | ||

| Immunosuppressive drug use | |||

| Yes | 130 | 100 | - |

| Mean Values | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 3.79 ± 1.47 | (Min 1, max 6) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 42.24 ± 13.99 | (Min 18 years, max 72 years) | |

| Length of hospital stay (mean ± SD) | 16 ± 5.71 days | (Min 3 days, max 32 days) | |

| Time after kidney transplant (mean ± SD) | 9.17 ± 5.65 years | (Min 1 years, max 20 years) | |

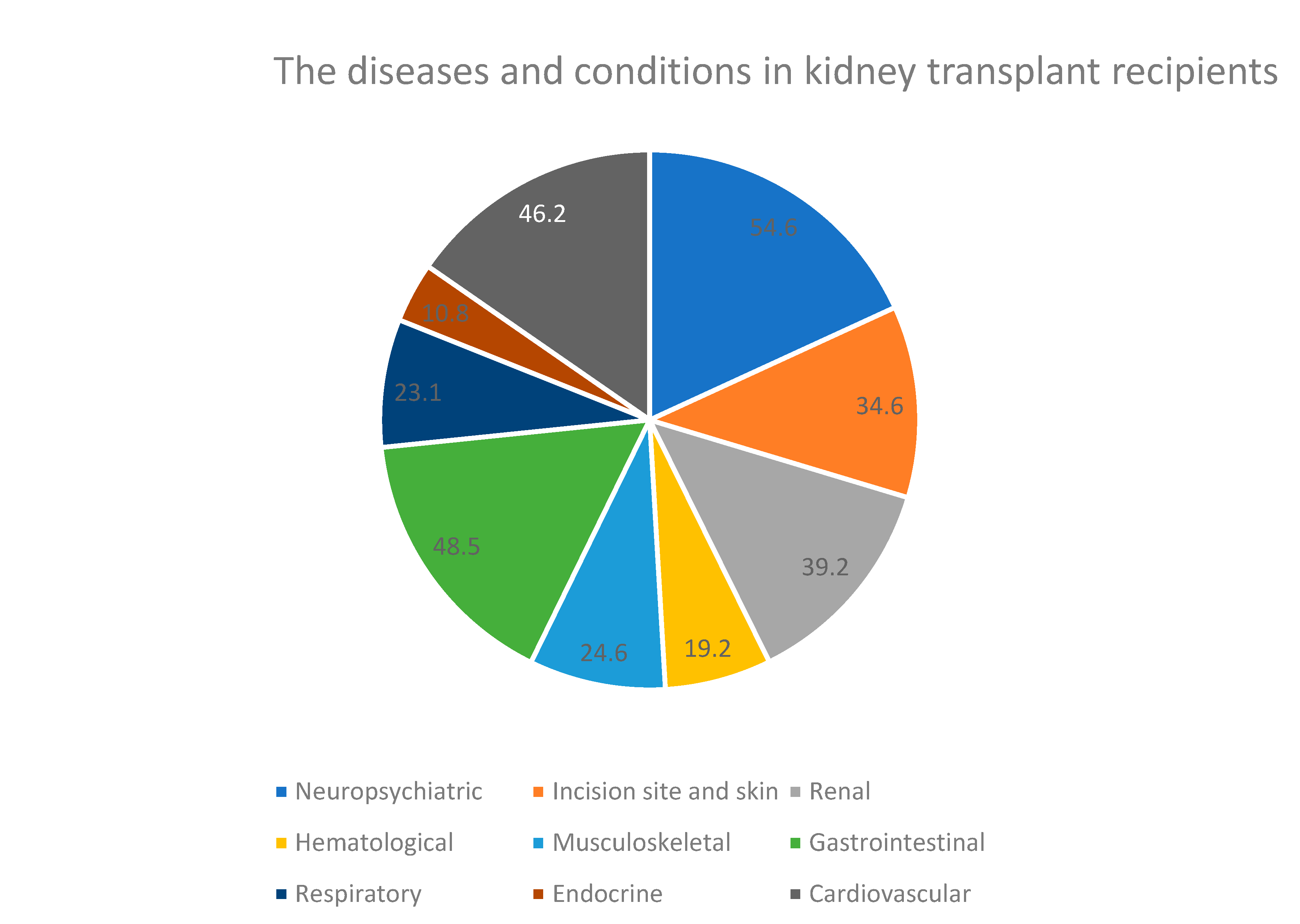

| Diseases and Conditions a | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Heart failure | 35 | 26.9 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 21 | 16.2 |

| Hypertension | 60 | 46.2 |

| Hypotension | 7 | 5.4 |

| Palpitation | 32 | 24.6 |

| Endocrine | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 | 10.8 |

| Thyroid, pancreas, liver problems | 14 | 10.8 |

| Respiratory | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma | 12 | 9.2 |

| Chest pain | 13 | 10.0 |

| Pneumonia | 30 | 23.1 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 17 | 13.1 |

| Constipation | 16 | 12.3 |

| Diarrhea | 25 | 19.3 |

| Heartburn | 46 | 35.4 |

| Increased appetite | 63 | 48.5 |

| Decreased appetite | 14 | 10.8 |

| Disruption of the oral mucosa | 9 | 6.9 |

| Dental problems | 45 | 34.6 |

| Gum problems | 42 | 32.3 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Muscle cramps, osteoporosis, arthritis | 32 | 24.6 |

| Osteopenia | 19 | 14.6 |

| Hematologic | ||

| Anemia | 25 | 19.2 |

| Renal | ||

| Urinary system infection | 51 | 39.2 |

| Kidney stone, tumor, prostatic hyperplasia | 13 | 10 |

| Urea/creatinine elevation | 32 | 24.6 |

| Acute kidney failure | 34 | 26.2 |

| Kidney rejection | 14 | 10.8 |

| Incision site and Skin | ||

| Delay in surgical wound healing (bleeding, hematoma, wound dehiscence) | 7 | 5.4 |

| Common skin changes (redness, discoloration, bruising, cracks) | 37 | 28.5 |

| Dry skin and rash | 45 | 34.6 |

| Neuropsychiatric | ||

| Stroke, cerebrovascular disease | 3 | 2.3 |

| Sleeping disorders | 30 | 23.1 |

| Clouding of consciousness | 11 | 8.5 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 29 | 22.3 |

| Memory deterioration | 9 | 6.9 |

| Vertigo | 14 | 10.8 |

| Tiredness | 71 | 54.6 |

| Unrest | 35 | 26.9 |

| Anxiety | 19 | 14.6 |

| Hopelessness | 26 | 20 |

| Social isolation | 30 | 23.1 |

| Loneliness | 27 | 20.8 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 35 | 26.9 |

| Other | ||

| Pain | 65 | 50 |

| Dehydration | 6 | 4.6 |

| Other (COVID-19, drug interaction, bronchiectasis, amyloidosis) | 7 | 5.4 |

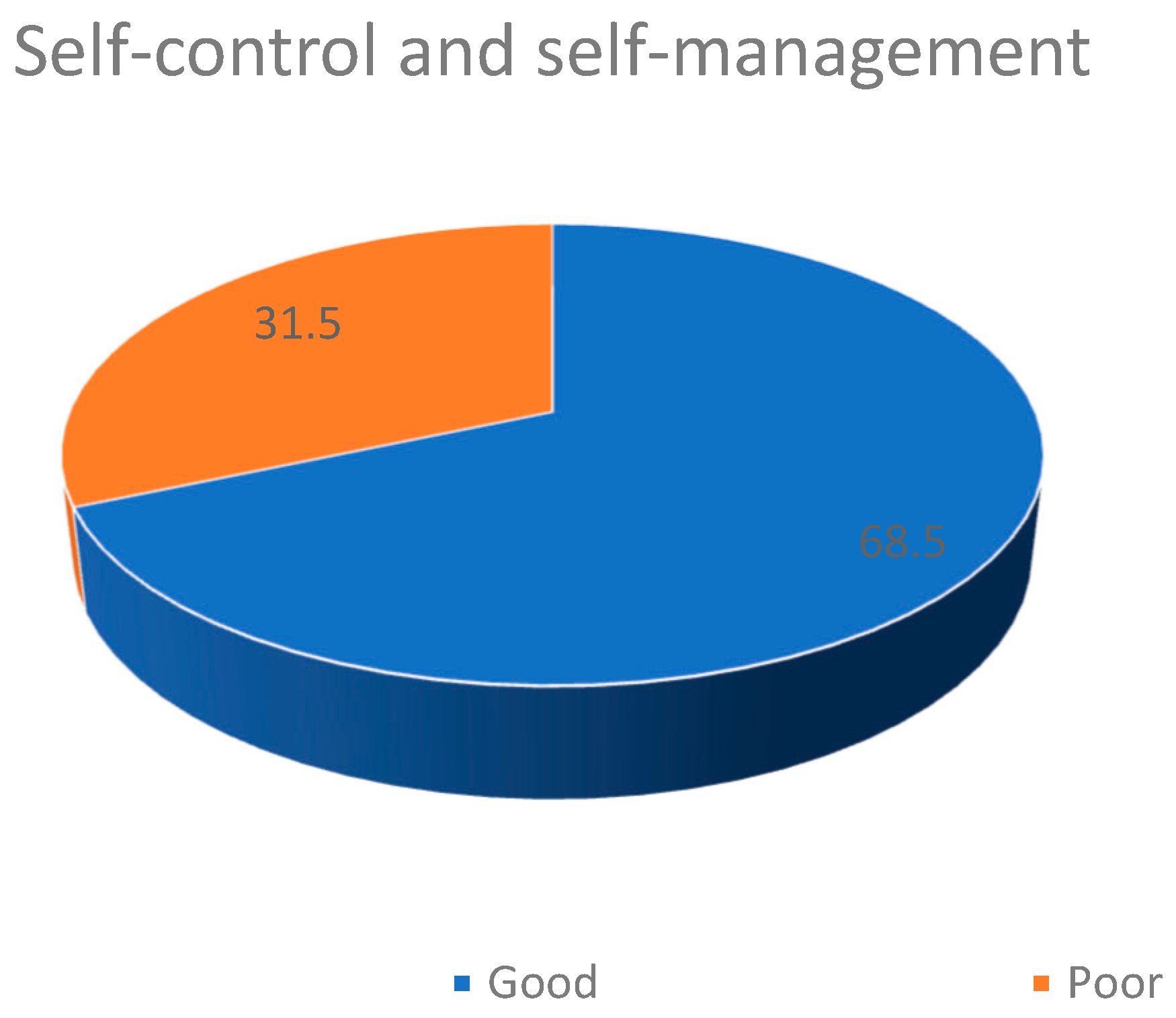

| Scales and Subscales | Items | Mean ± SD | Min. | Max. | CCI Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCMSS Total Score | 1–16 | 69.83 ± 11.77 | 31 | 91 | r = −0.403, p = 0.011 * |

| Self-monitoring | 1–6 | 29.51 ± 5.11 | 11 | 36 | r = −0.511, p = 0.0321 * |

| Self-evaluating | 7–11 a | 17.25 ± 6.07 | 0 | 25 | r = 0.048, p = 0.552 |

| Self-reinforcing | 12–16 | 23.06 ± 5.23 | 5 | 30 | r = −0.021, p = 0.000 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simsek Yaban, Z.; Bulbuloglu, S. Examination of Long-Term Diseases, Conditions, Self-Control, and Self-Management in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantology 2025, 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020013

Simsek Yaban Z, Bulbuloglu S. Examination of Long-Term Diseases, Conditions, Self-Control, and Self-Management in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantology. 2025; 6(2):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020013

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimsek Yaban, Zuleyha, and Semra Bulbuloglu. 2025. "Examination of Long-Term Diseases, Conditions, Self-Control, and Self-Management in Kidney Transplant Recipients" Transplantology 6, no. 2: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020013

APA StyleSimsek Yaban, Z., & Bulbuloglu, S. (2025). Examination of Long-Term Diseases, Conditions, Self-Control, and Self-Management in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantology, 6(2), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6020013