1. Introduction

The generation and manipulation of complex structured light fields with scattering media have emerged as novel research topics, enabling advanced control over spatial distributions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], polarization states [

7,

8,

9,

10], spectral modulation [

11,

12,

13,

14], and energy allocations [

15,

16,

17]. Wavefront shaping techniques have been particularly instrumental in advancing phase and polarization control of light transmitted through scattering media. The transmission matrix (TM) model has proven highly effective for characterizing light propagation in such complex systems [

18,

19]. Building on this framework, Tripathi et al. pioneered the measurement of a vector transmission matrix (VTM) for scattering media using a four-step phase-shifting method [

20], enabling targeted focusing and manipulation of the transmitted light field via phase conjugation [

21].

Unlike ordered media such as metasurfaces, the amplitude, phase, and polarization state of an optical field become randomly distorted due to multiple scattering events in a HASM. In this context, theoretical models have been developed which establish new equations for intrinsic and extrinsic coefficients to describe these intensity gradients [

22]. Some related studies have also clarified the inter-relationships among atomic structure, incident energy, and scattering characteristics [

23]. Conversions among all polarization components including linear, circular, and elliptic polarization components occur, introducing greater complexity in field evolution while simultaneously offering additional degrees of freedom for optical manipulation. In particular, it is challenging to directly describe the linear–circular polarization conversion and polarization transformation of each polarization component of an input beam via HASM. That is, multiple output polarization components can be generated and manipulated from each polarization component of an input beam via HASM. Nevertheless, more effective and intuitive methods for describing the evolution of polarization state is still needed to enable convenient manipulation of scattering light, especially regarding polarization component conversions.

Caustics, bright focal structures arising from wave interactions, are fundamental phenomena observed across all wave domains [

24]. In optics, caustics manifest at interfaces with smooth surfaces and are classified by geometric characteristics into seven elementary catastrophe types [

25]. For example, Airy beams correspond to fold catastrophes [

26], Pearcey beams to cusp catastrophes [

27], and Swallowtail beams to swallowtail catastrophes [

28]. Following Greenfield E et al’s demonstration of nonbroadening optical beams propagating along arbitrarily chosen convex trajectories in space, recent advances have enabled flexible control of caustic vector beams through phase engineering of orthogonal polarization components [

29], with metasurfaces offering expanded application pathways [

30]. Caustic beams have found numerous applications, including micro-particle manipulation [

31], light–matter interaction [

32], optical communication [

33], and high-resolution imaging [

34]. However, these applications are limited by classic resolution constraints, and typically only a single caustic field can be generated and manipulated from a given input field. As a breakthrough of caustic beam engineering, the simultaneous generation and manipulation of multiple arbitrary curved beams (including Gaussian and vortex beams) with high-resolution, diverse polarization states and controlled vorticity offers considerable potential for advancing optical functionality.

In this work, we theoretically and experimentally demonstrate the generation and manipulation of multiple arbitrary polarized curved caustic beams with high-resolution, diverse polarization states, and controlled vorticity via a HASM. The traditional vector transmission matrix mainly focuses on the evolution of two orthogonal polarization components in scattering medium [

20], without explicit description of polarization control of various polarization components. According to the difference between two orthogonal components’ diffraction indexes, two caustic beams with orthogonal polarization components can be generated through a specially designed metasurface [

30]; the resolution of generated caustic beams depends on the size of unit cell. In this work, our approach can simultaneously generate multiple caustic beams with arbitrary polarization states. An extended polarization transmission matrix (EPTM) is proposed to intuitively describe the evolution and manipulation of each of the orthogonal polarization components passing through a HASM, providing a more effective and convenient framework for generating and manipulating multiple high-resolution caustic light beams with freely designed trajectories, diverse polarization states, tunable energy weight ratios, and custom spatial profiles through polarization transformation. This method establishes unprecedented flexibility in controlling optical field properties, leveraging the unique characteristics of HASM to enable polarization transformation of each input orthogonal polarization component.

2. Polarization Transformation via HASM for Caustic Beam Generation and Control Using EPTM

To intuitively describe the evolution of different polarization components in an optical field passing through a HASM, we introduce an extended polarization transmission matrix (EPTM). It describes the process of transformation and control of output multiple various polarization components from one polarization component; the measurement stability and conditioning of the EPTM are similar to that of traditional vector TM. According to Maxwell’s equations and Green’s function [

35], the physical model of light field transmission through a scattering medium can be described as

where

is the output optical field from scattering medium, and

and

are the discretized Green function and the input optical field of the input field, respectively. The output light field at a given position is essentially formed by the linear superposition of the incident light field. The connection between the output and input light fields was established by the discretized Green function

, which can be represented in term of the corresponding complex TM. Within the VTM framework, the input–output relationship for the optical field is defined as [

36,

37]

where

j and

k represent any orthogonal polarization states, and

and

are the optical field represented by Jones vectors in the output

and input

planes, respectively. Here,

,

and

,

represent complex amplitudes of the orthogonal polarization components. The VTM is structured as four

submatrices (

,

,

, and

), yielding an overall dimensionality of

, where

M and

N denote the number of discrete sampling points on the output and input planes, respectively. Each element

quantifies the contribution of the

k-polarized component at input point

to the

j-polarized component at output point

. To account for linear–circular polarization conversion in HASM, the VTM can be transformed between the linear and circular polarization bases. For circular polarization representation,

where

, and

;

l,

r,

x, and

y, respectively, represent left-handed circular polarization, right-handed circular polarization, and orthogonal linear polarization. Conversely, the linear polarization components derive from circular components via

where

and

. The left- and right-handed circularly polarized components can also be derived from the horizontal and vertical linearly polarized components. The four submatrices

,

,

, and

in the VTM act independently on each input polarization component. From the above equation, it can be seen that arbitrary polarization state and focusing distances can be realized in the observation plane by adjusting the four submatrices

,

,

, and

in the VTM.

Due to the depolarization effect of anisotropic materials (e.g., ZnO HASM), we can rewrite Equations (

3) and (

4) as

and

where 1 and 2 represent two orthogonal polarization components, either linear or circular, respectively. Equations (5) and (6) can be combined into a single expression as follows:

where

, with

a as either 1 or 2. The EPTM is used to uniformly represent the transmission matrices of each polarization state:

The relation between the input light field

and the output light field

can be obtained using the EPTM as

Furthermore, any polarization components can be regarded as coherent superpositions of two orthogonal polarization components:

, where

is an arbitrary polarization component and µ and

are corresponding complex coefficients. Accordingly, the EPTM can be generalized as follows:

Therefore, diverse polarization components can be flexibly generated and manipulated through polarization transformation of each input polarization component, as described in Equation (

10). In this work, for simplicity, we select the

and

linear polarization components, as well as the right- and left-circular polarization components as the output polarization states for manipulation. In particular, polarization conversion can be flexibly manipulated, and multiple beams with desired polarization states can be compactly generated by modulating the submatrices of the EPTM with specially designed phase profiles (e.g., caustic phases).

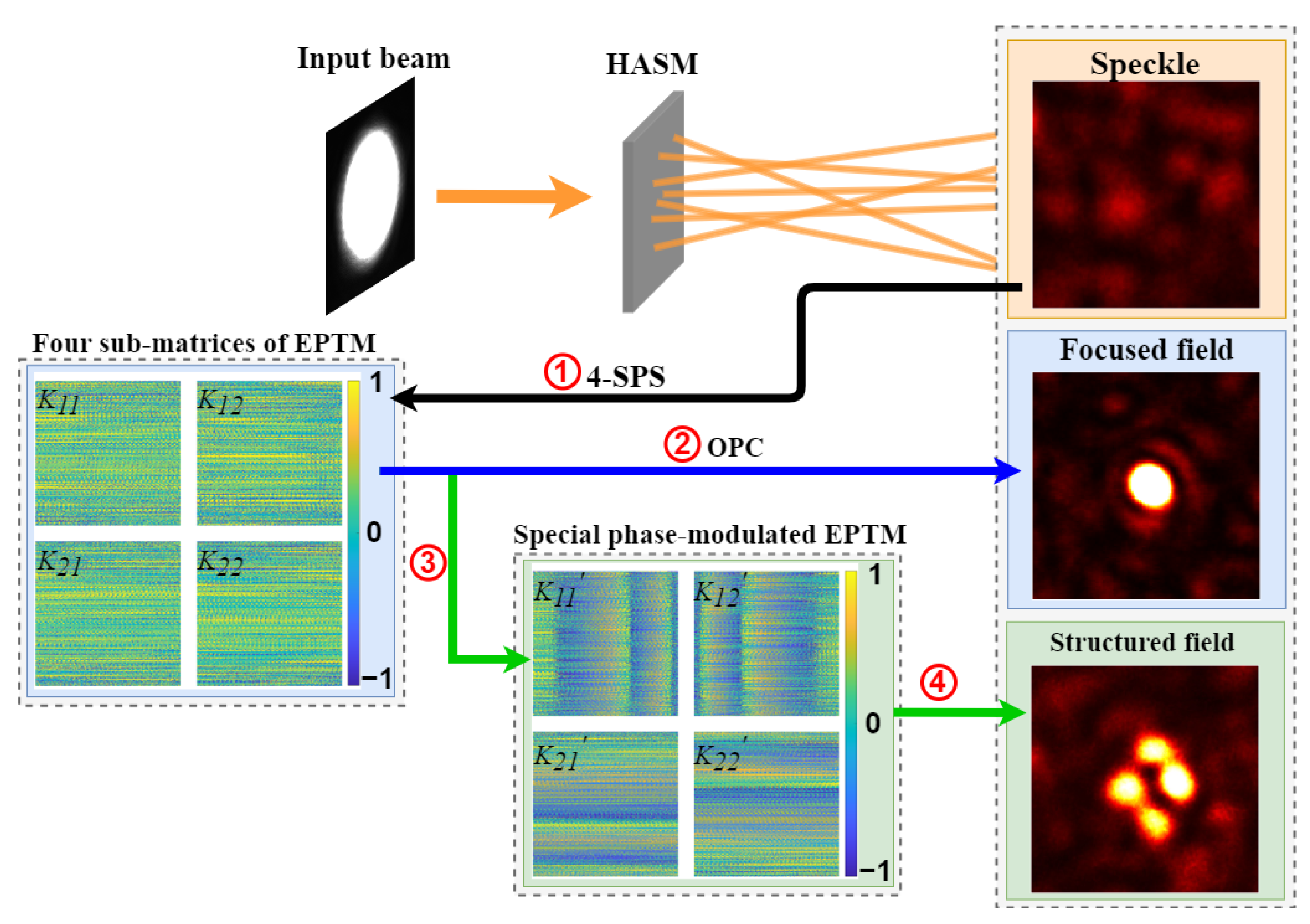

A flowchart of the specific processes in our approach is illustrated in

Figure 1. The process of generating high-resolution polarized light fields after incident light passes through a HASM is illustrated in

Figure 2. When the input light beam passes through an isotropic scattering medium, such as ground glass, conversion between linear and circular polarization components does not occur [

38]. In this case, only the EPTM elements that map identical polarization components between the incident and output lights are non-zero. In contrast, linear–circular polarization conversion appears when the beam passes through an anisotropic scattering medium (e.g., ZnO HASM). This results in all elements of the EPTM becoming non-zero, indicating that a single input polarization component can be transformed into multiple output polarization components. The polarization state of the transmitted light captured by the CCD is examined using a quarter-wavelength plate (QWP) and polarization (P) plate, and the four-step phase-shifting method is employed to measure each element in the submatrices of the EPTM [

39]. Optical phase conjugation (OPC) applied to the EPTM enables precise focusing of polarized beams at arbitrary positions in the imaging plane [

10,

18]. By applying tailored phase modulation to the EPTM submatrices, structured beams with arbitrary polarization states and phase profiles can be generated after transmission through the HASM.

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow for polarization transformation of each input orthogonal polarization component via HASM, enabling simultaneous generation and manipulation of multiple structured beams with arbitrary trajectories and polarization states. When a vector beam traverses the HASM, it produces a speckle pattern with spatially varying states of polarization (SoPs), which is recorded. Each element of the EPTM submatrices is then computed using four phase-shifted speckle patterns. Optical phase conjugation (OPC) applied to the EPTM yields compensation phase maps for the orthogonal polarization components of the input field, effectively offsetting the scattering effect of HASM. Structured beams with arbitrary polarization states and phase profiles can be generated via HASM by applying tailored phase modulation to the submatrices of the EPTM, corresponding to the polarization transformation for each input orthogonal polarization component.

3. Experimental Generation and Control of Arbitrary Curved Caustic Beams via HASM with Tunable Polarization, Energy Weighting, and Vorticity

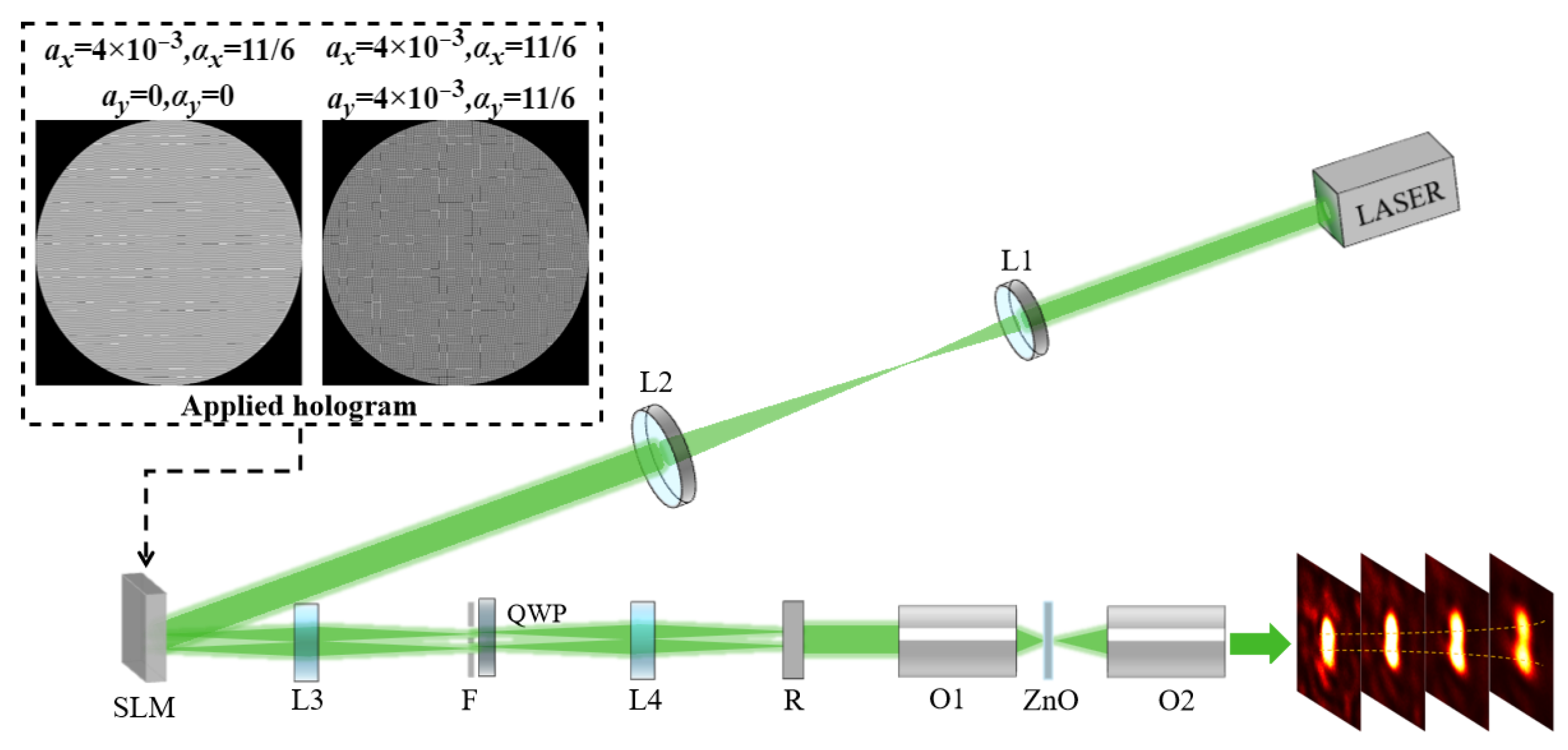

The experimental setup for measuring the EPTM and generating arbitrary curved caustic optical fields is shown in

Figure 3. A laser beam (Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd., CNI, Changchun, China; Model MGL-III-532) with 532 nm passes through a beam-expanding and collimation system (L1 and L2), then reaches a spatial light modulator (SLM) (HoloEye-Pluto 2; resolution: 1920 × 1080 pixels; pixel pitch: 8.0 µm) loaded with two-dimensional holograms. The middle part of the spatial light modulator is extracted as the effective incident area with 32 × 32 grids; each grid contains 33 × 33 pixels. Experimental results indicate that the experimental accuracy and efficiency of the output optical field are improved with increasing grids. In this work, 32 × 32 grids are adopted considering the calculation of consumption and experimental results. The modulated beam is reflected into a

system. The

diffraction orders in the

x and

y directions pass through a dual-aperture spatial filter

F, resulting in left- and right-circular polarization (or orthogonal linear polarization) via two orthogonally oriented quarter-wave plates (

/4), (or two half-wave plates (

/2) positioned at an intersecting angle of 45°). The orthogonal circularly polarized components (or orthogonal linearly polarized components) are combined using a Ronchi grating to generate a vector beam. The two-dimensional modulation function loaded onto the SLM is

where

represents the modulation depth, which is set to 1 in this work.

represents the spatial carrier frequency.

and

represent the phase distributions carried by the left- and right-circularly polarized components (or orthogonally linear polarized components), respectively. The resulting vector light field can be expressed as follows:

where

is the amplitude. When

(or

), the vector light can be regarded as the superposition of two orthogonal circular polarization components (or two orthogonal linear polarization components). The resulting vector beam is focused onto the HASM (a ZnO HASM was used in this experiment) using a microscope objective O1 (10×, NA 0.25), and the output field scattered by the ZnO HASM is collected by another microscope objective O2 (20×, NA 0.40). The center region of the speckle pattern, consisting of 32 × 32 grids, is extracted as the effective sampling area. The EPTM is then measured using the four-step phase-shifting method by selectively filtering different polarization components of the speckle. Based on the optical phase conjugation (OPC) technique [

38], the phase distributions

and

(† denotes the conjugation) are, respectively, applied to the orthogonally circular polarized components (or orthogonal linear polarization components) to counteract the scattering effect and generate the desired vector beam. Accordingly, the modulation function loaded onto the SLM can be expressed as

An arbitrary number of polarization components can be generated and manipulated by modulating the corresponding submatrix of EPTM , using the phase condition (or ) = Arg() derived from each input orthogonal polarization component.

The caustic vector light field transmitted along the curve can be expressed as [

30]

where

is the amplitude,

or

, and

is an arbitrary polarization state vector basis.

a is the caustic coefficient,

is associated with different polynomial acceleration profiles,

,

is the wavelength, and

L is the size of hologram. When the caustic phases are independently integrated into the submatrices of the EPTM, multiple caustic beams with diverse polarization states and propagation curves can be generated and manipulated. In this work, unless otherwise specified, the parameters are set as

,

= 11/6, and

L = 0.0086 m. Left- and right-handed circularly polarized light (or orthogonally linear polarized light) are modulated by the wavefront phases

and

, respectively, to enable the generation and manipulation of the arbitrary curved caustic beams with various polarization states. The corresponding two holograms with

and

for generating a single caustic beam and two caustic beams are shown in

Figure 3.

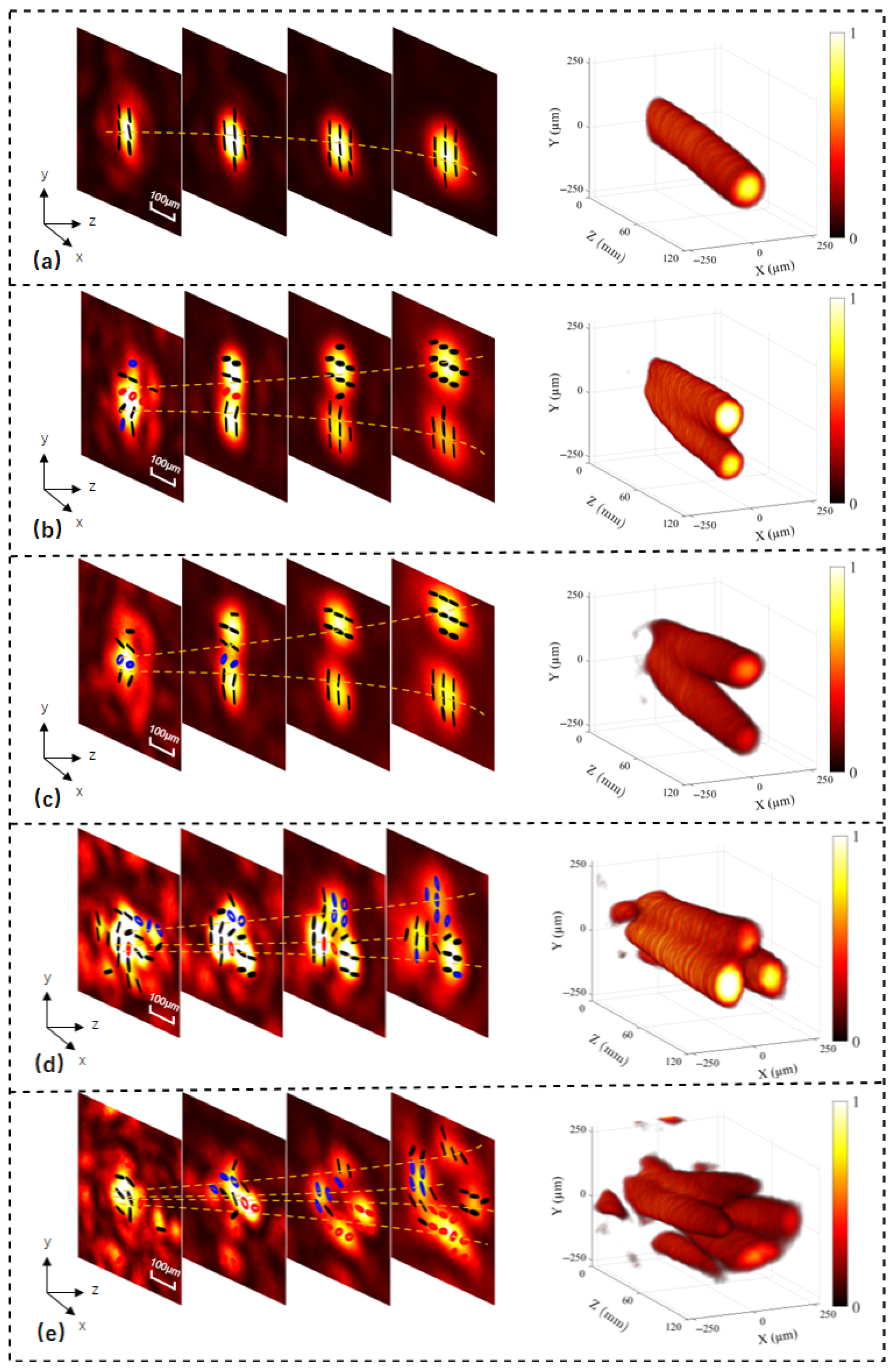

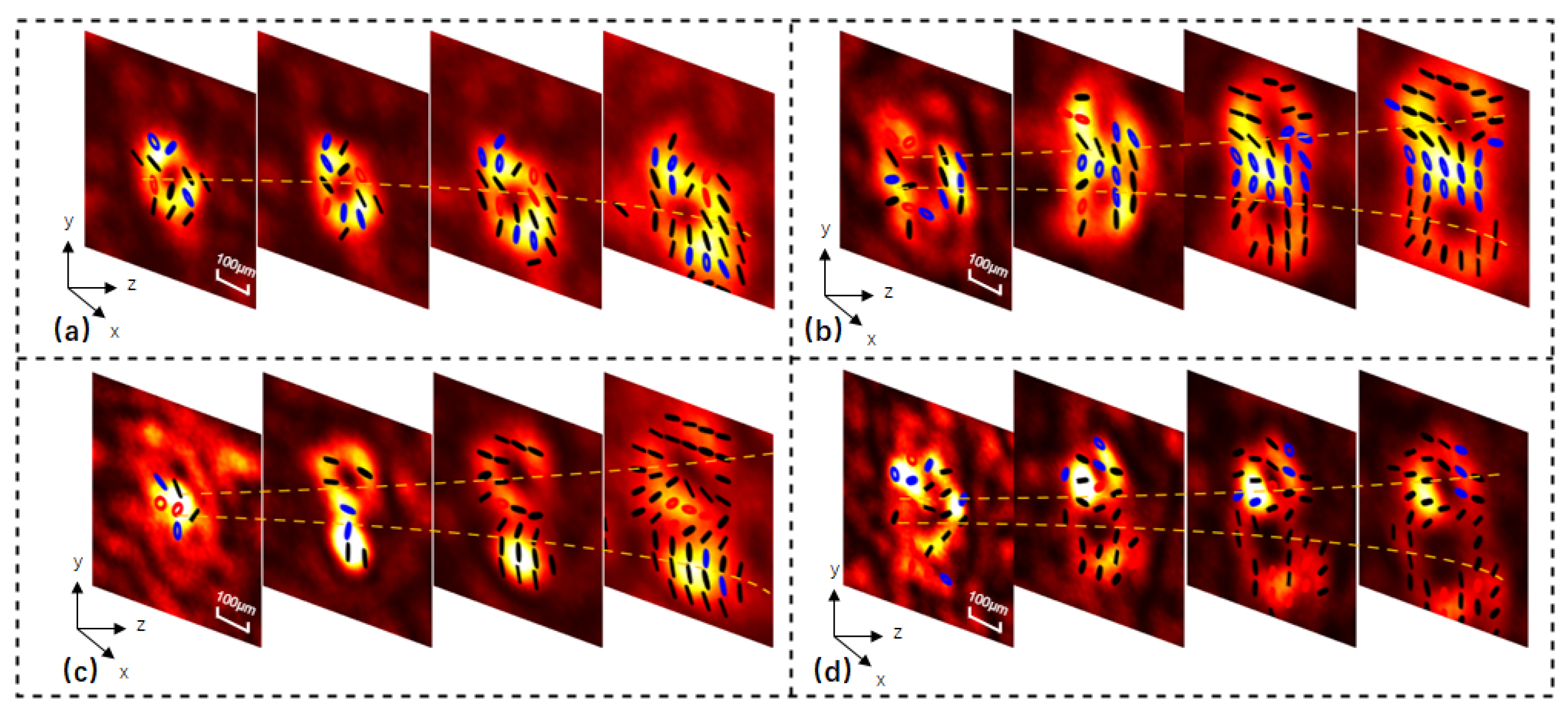

The experiment results of multiple caustic beams with various polarization states, generated by polarization multiplexing each of the input orthogonal polarization components via ZnO HASM, are shown in

Figure 4. Axial profiles captured at 30 mm intervals (left side of each panel) reveal progressively complex configurations: (a) a single linearly polarized, diffraction-resistant caustic beam; (b) a pair of orthogonally linearly polarized beams propagating along opposite transverse-shift trajectories; (c) orthogonally linearly polarized caustic beams transmitted along distinct trajectories with

= 11/6 and 7/4; (d) two orthogonally linearly polarized caustic beams and one circularly polarized caustic beam; (e) two orthogonally linearly polarized caustic beams and two orthogonally circularly polarized caustic beams. In the figure, linear polarization states are represented by black lines, whereas left-handed circular polarization is shown in blue and right-handed by red. This color scheme is used consistently throughout the text. Moreover, compared to conventionally generated caustic beams [

30,

40,

41], this combinatorial control enables the simultaneous generation of multiple independent caustic beams with arbitrarily designated polarization states.

A generated structured optical field can be regarded as a coherent superposition of multiple caustic beams with distinct polarization states. The polarization state of each caustic beam serves as an additional degree of freedom that can be freely controlled. Owing to the polarization conversion capability of ZnO HASM, caustic beams with arbitrary polarization states, including orthogonal linear polarizations and combinations of linear and circular polarizations, can be generated. As shown in

Figure 5a,b, the total light intensity and the corresponding polarization components are visualized. As established in Refs. [

42,

43], caustics will only occur in the presence of a shift or oblique wave in the input field. In this work, with the phase modulation (1 <

< 2), the formed beams are likely deflected due to the oblique wavefront (see Equation (

13)).

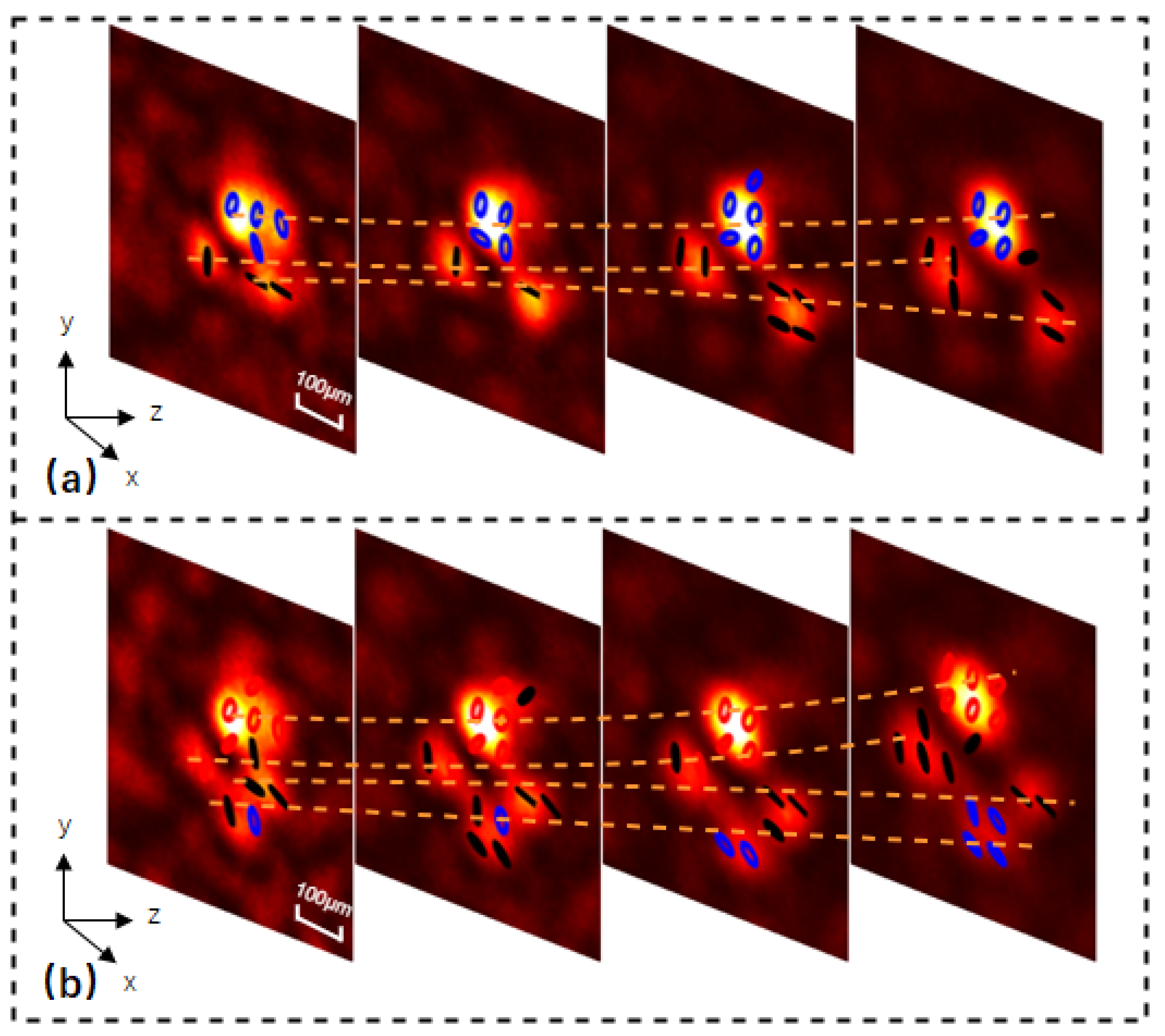

Building on this foundation, more complex caustic beams can be engineered by incorporating phase masks with tailored phase profiles, such as vortex phases, into the transmission matrix. As a representative example, we consider the introduction of a vortex phase mask. This enables the generation of caustic vortex beams exhibiting diverse polarization states and topological charges

m, each propagating along distinct trajectories after transmission through the ZnO HASM, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Specifically,

Figure 6a shows a scalar caustic vortex beam with

;

Figure 6b presents two caustic vortex beams with orthogonally linear polarizations, opposite transverse-shift trajectories, and

; and

Figure 6c displays a pair consisting of a caustic vortex beam with

and a caustic Gaussian beam, both with orthogonal linear polarizations.

Figure 6d features two caustic vortex beams with orthogonally linear polarizations and topological charges

and

.

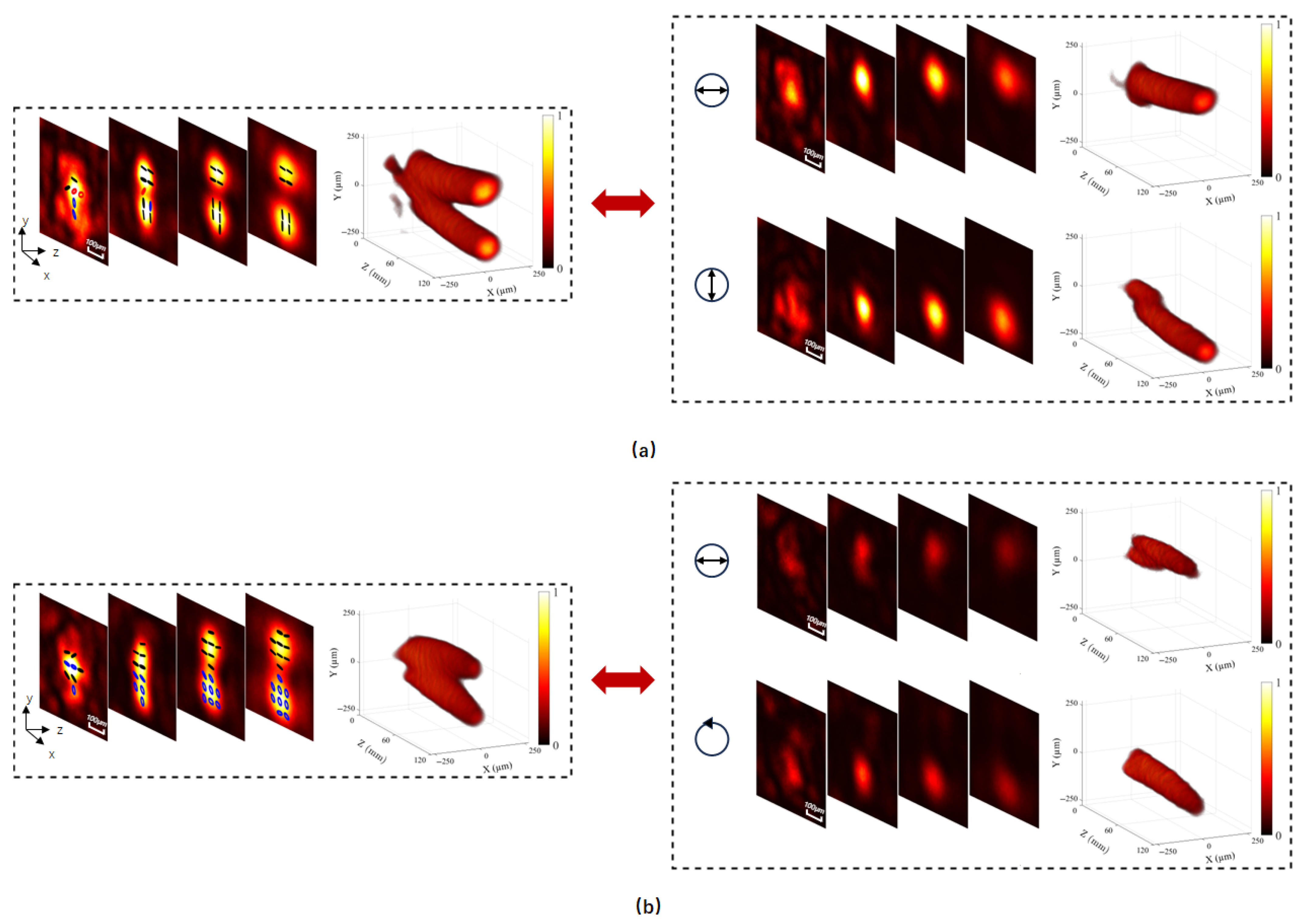

Since each orthogonal polarization component of the incident light can be independently polarization-transformed, we can control the number of caustic beams generated by each of the components, thereby producing multiple caustic beams with different energy weight ratios, as shown in

Figure 7, with an exposure interval of 15 mm. In

Figure 7a, one polarization component of the input field is modulated to produce a single caustic beam with left-handed circular polarization, while the other orthogonal component of the input field is converted into two caustic beams with 0° and 90° linear polarization. As a result, three caustic beams are generated: the left-handed circularly polarized beam carries an energy weight ratio of 1/2 relative to the total field energy, and each of the linearly polarized beams carries a ratio of 1/4. In

Figure 7b, one polarization component of the input field is modulated to produce three caustic beams with horizontal linear, vertical linear, and left-handed circular polarization. The other orthogonal component is converted into a single caustic beam with right-handed circular polarization. In this case, the right-handed circularly polarized beam carries an energy weight ratio of 1/2, while each of the remaining three beams carries a ratio of 1/6, as shown in

Figure 7b. In particular, the irregular proportions of the beam energy are not arbitrary, the energy of each orthogonal polarization component is equally divided into its generated beams. Therefore, the energy proportions of three and four beams under the above mentioned conditions are (1/2, 1/4, 1/4) and (1/2, 1/6, 1/6, 1/6), respectively.

To date, we have successfully generated multiple high-resolution optical beams with arbitrary polarization states, complex phase profiles, and tunable energy weight ratios, all propagating along arbitrary trajectories after ZnO HASM. In principle, our method enables the generation of caustic beams with customizable polarization, phase, energy distribution, and propagation paths. This framework can be further extended to simultaneously produce multiple beams with arbitrary polarization states and complex phase structures, each following independently tailored trajectories. In this work, experiment results indicate that four caustic beam outputs, with various polarization states, is the maximum multiplexing capacity, the ouput optical field will degrade into a vague shape with more than four caustic beams. Such a capability holds strong potential for applications in high-resolution imaging, high-capacity optical communication, and precise light manipulation in scattering environments.

As recently demonstrated by Yuan et al. [

44], the selectivity and sensitivity of a sensor can be significantly enhanced by using customized light fields, opening up new avenues for environmental monitoring and biomolecular detection. The precise control capabilities of multi-degree-of-freedom (phase, polarization, mode) light fields demonstrated in this work provide a powerful toolkit for addressing the core challenges in the fields of optical sensing, micro-particle manipulation and complex microscopic manipulation of optical field. In the field of optical sensing, by using specifically designed structured light fields (such as vortex caustic beams with specific phase singularities) as detection probes, the unique ’fingerprint’ information carried after interacting with a material can be detected with high sensitivity. Customized multiple high-resolution caustic beams with various polarization states can play an important role in micro-particle manipulation [

45]. Therefore, these results of this work are not only a methodological advancement but also provide an expandable technical foundation for the aforementioned cutting-edge application fields.