Robust Covert Spatial Attention Decoding from Low-Channel Dry EEG by Hybrid AI Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work and Motivations

3. Methods

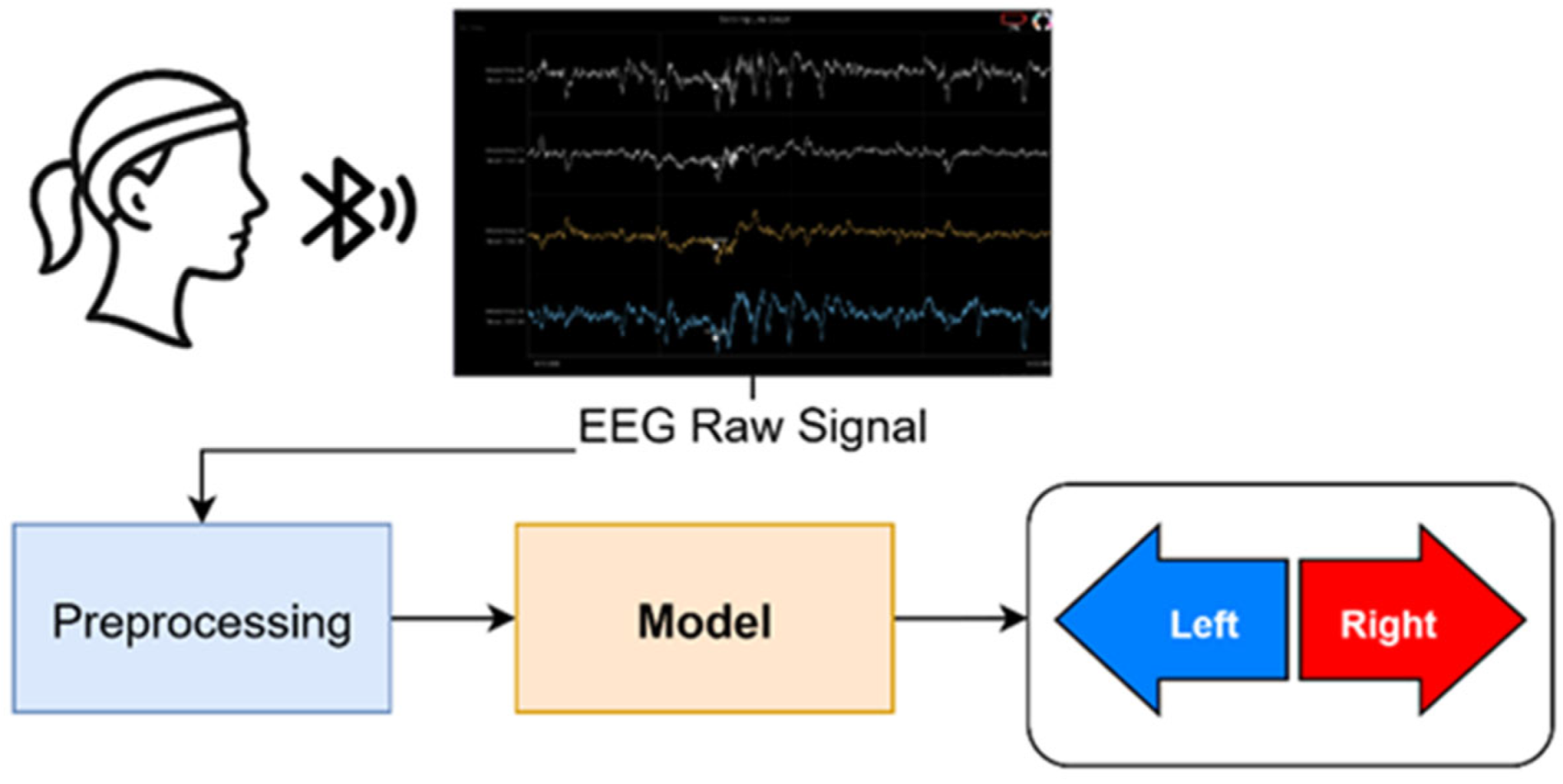

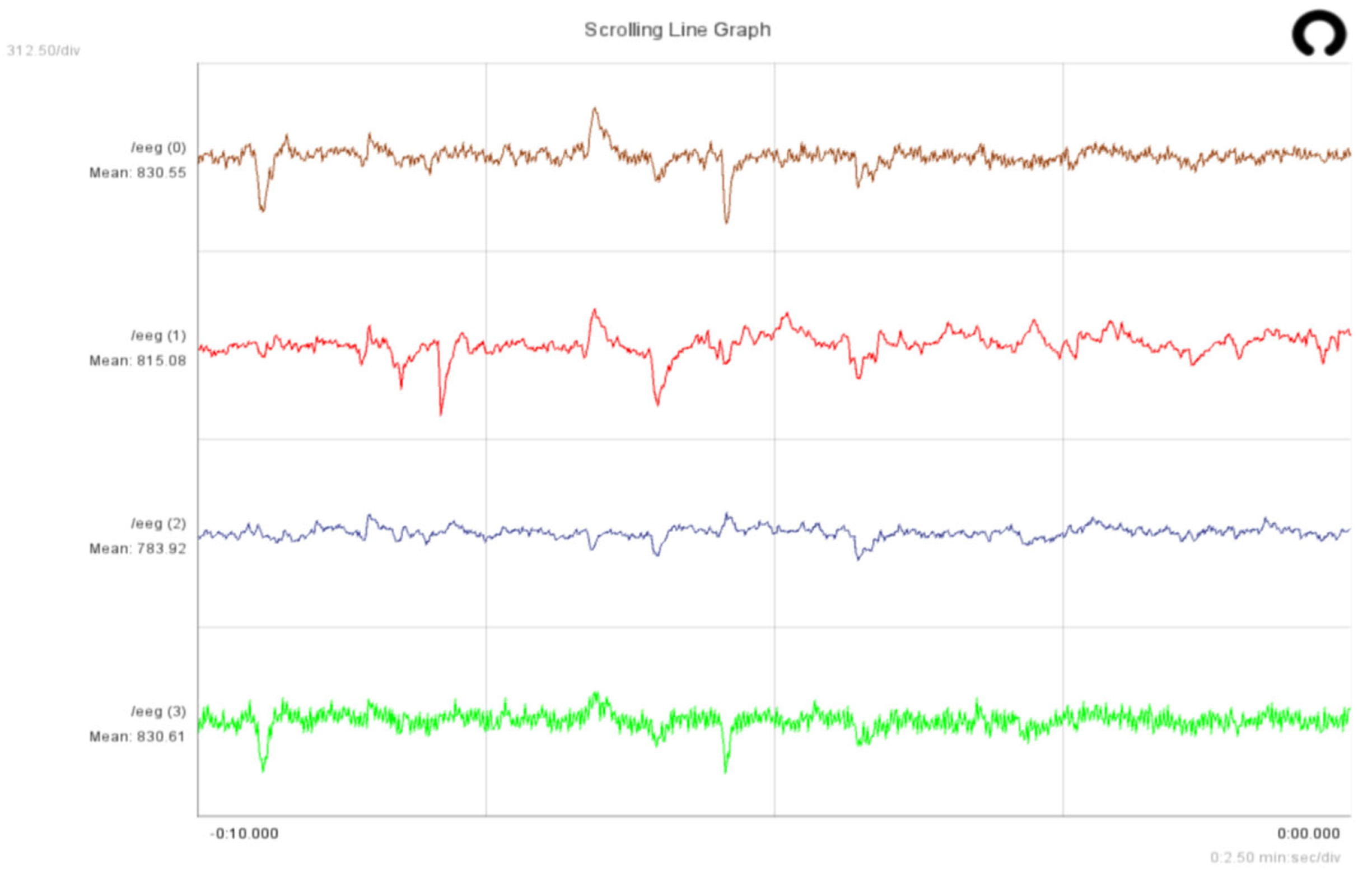

3.1. Setup and Task

3.2. Preprocessing

3.3. Features

3.4. Models and Learning

- Hybrid encoder: temporal depthwise conv (kernel 15, depth multiplier 4), pointwise conv to 32 channels, spatial depthwise conv over four channels; ELU + BatchNorm after each conv; dropout p = 0.25 after the convolutional stack.

- Temporal module: BiLSTM, 64 units per direction, dropout p = 0.2 between recurrent layers. Attention module: four heads, embed dim 128, head dim 32, pre-norm, MLP 256, attention and MLP dropout p = 0.1, stochastic depth p = 0.1.

- Classifier: global average pooling, linear with label smoothing ε = 0.1. Optimization: AdamW, initial learning rate 1 × 10−3, warm-up five epochs, cosine decay to 1 × 10−5, weight decay 1 × 10−4, gradient clip 1.0, batch size 64.

3.5. Augmentation and Supervised Consistency

3.6. Evaluation and Calibration

4. Results Analyses

4.1. Experimental Setup

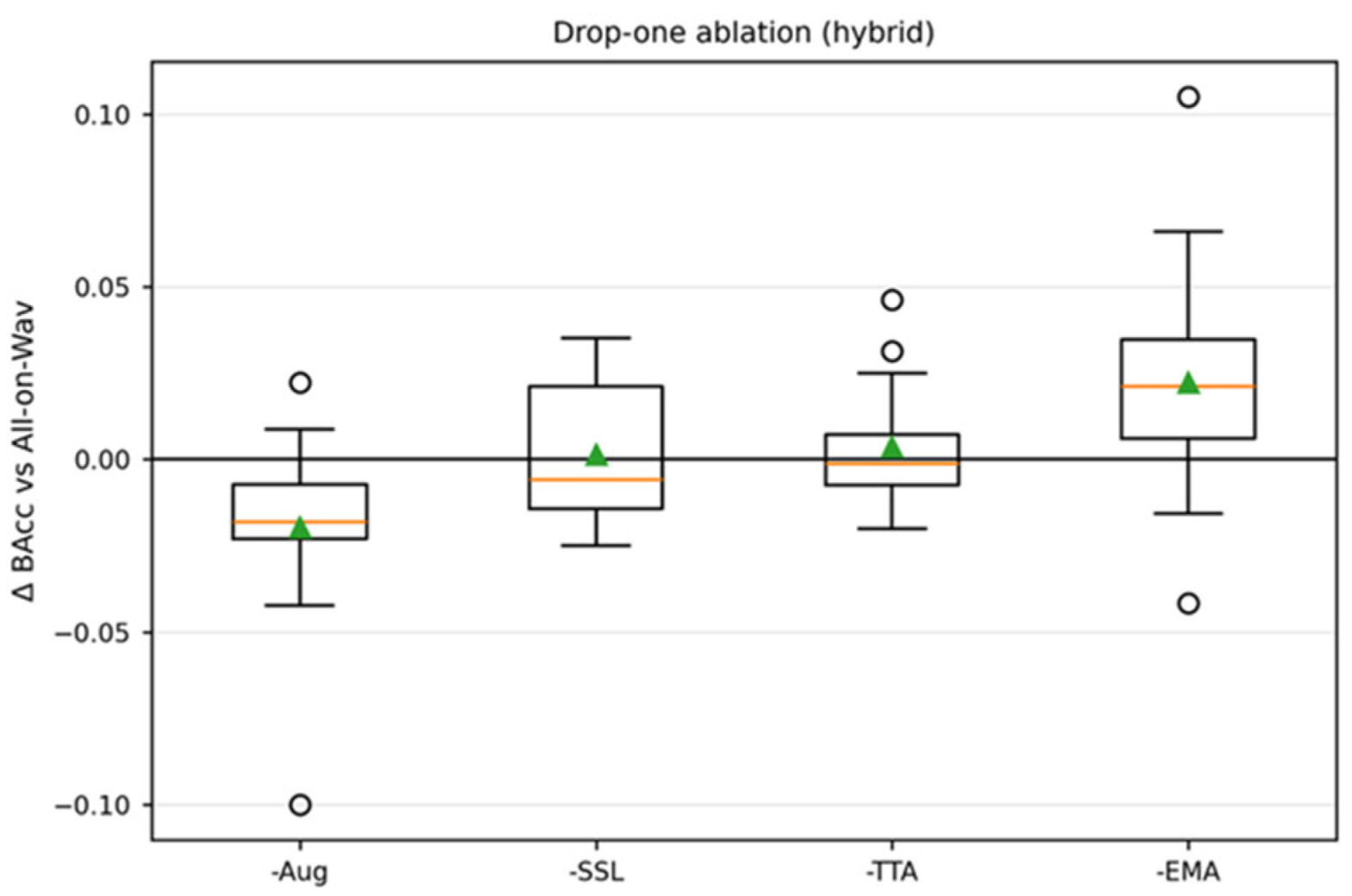

4.2. Topline Results and Contribution Analysis

4.3. Feature Families Under a Fixed Encoder

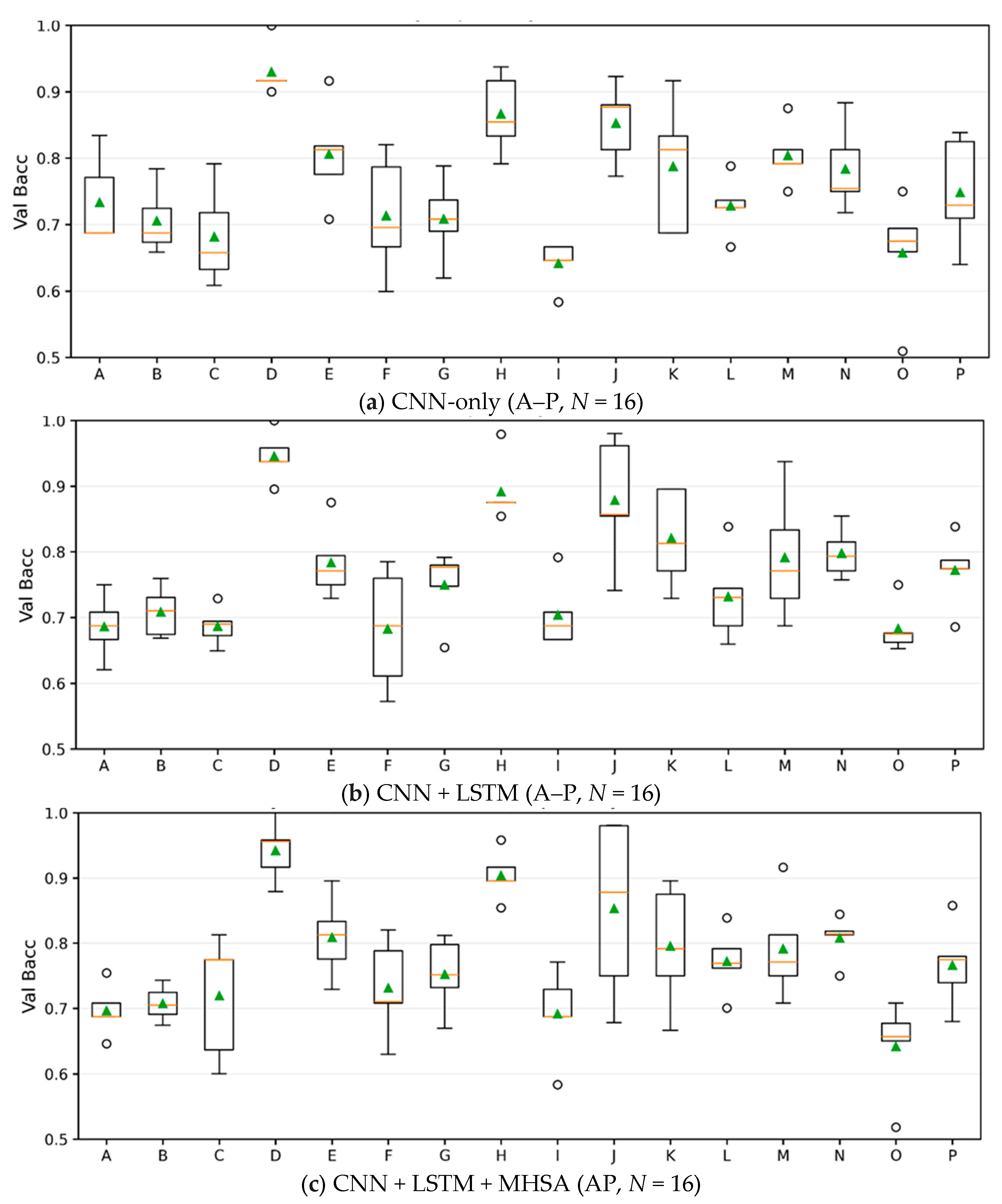

4.4. Model Sweep and Subject-Wise Distributions

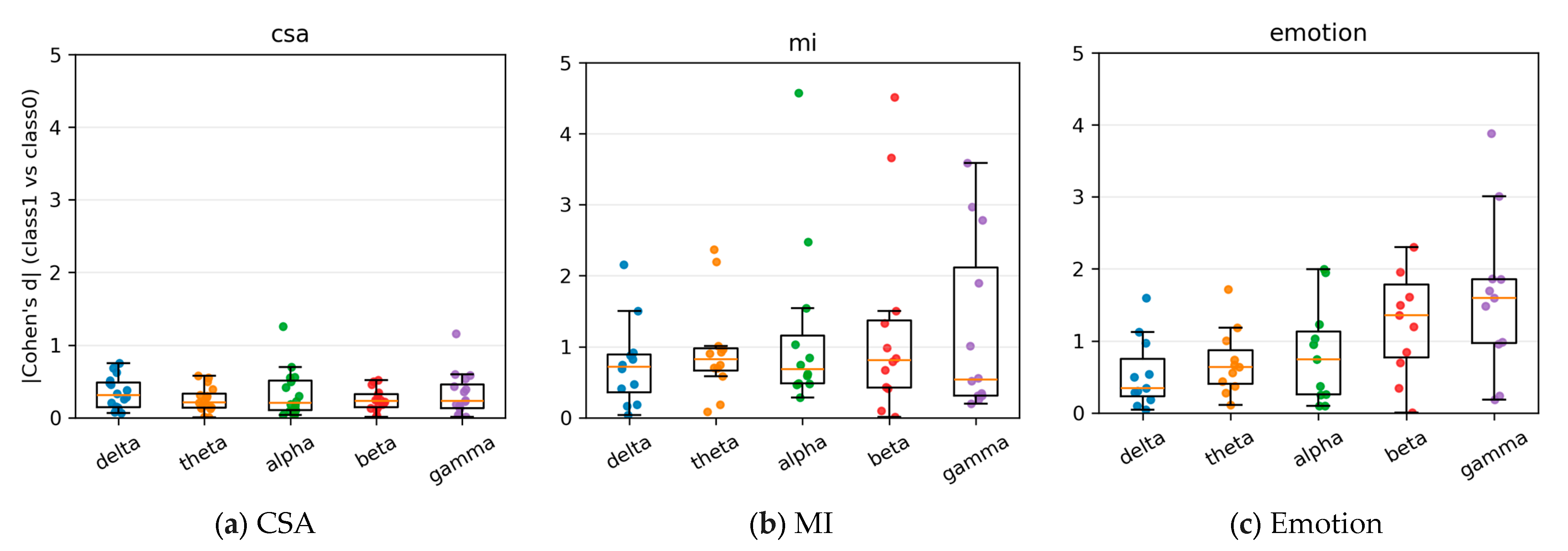

4.5. Cross-Task Comparison Under an Identical Pipeline

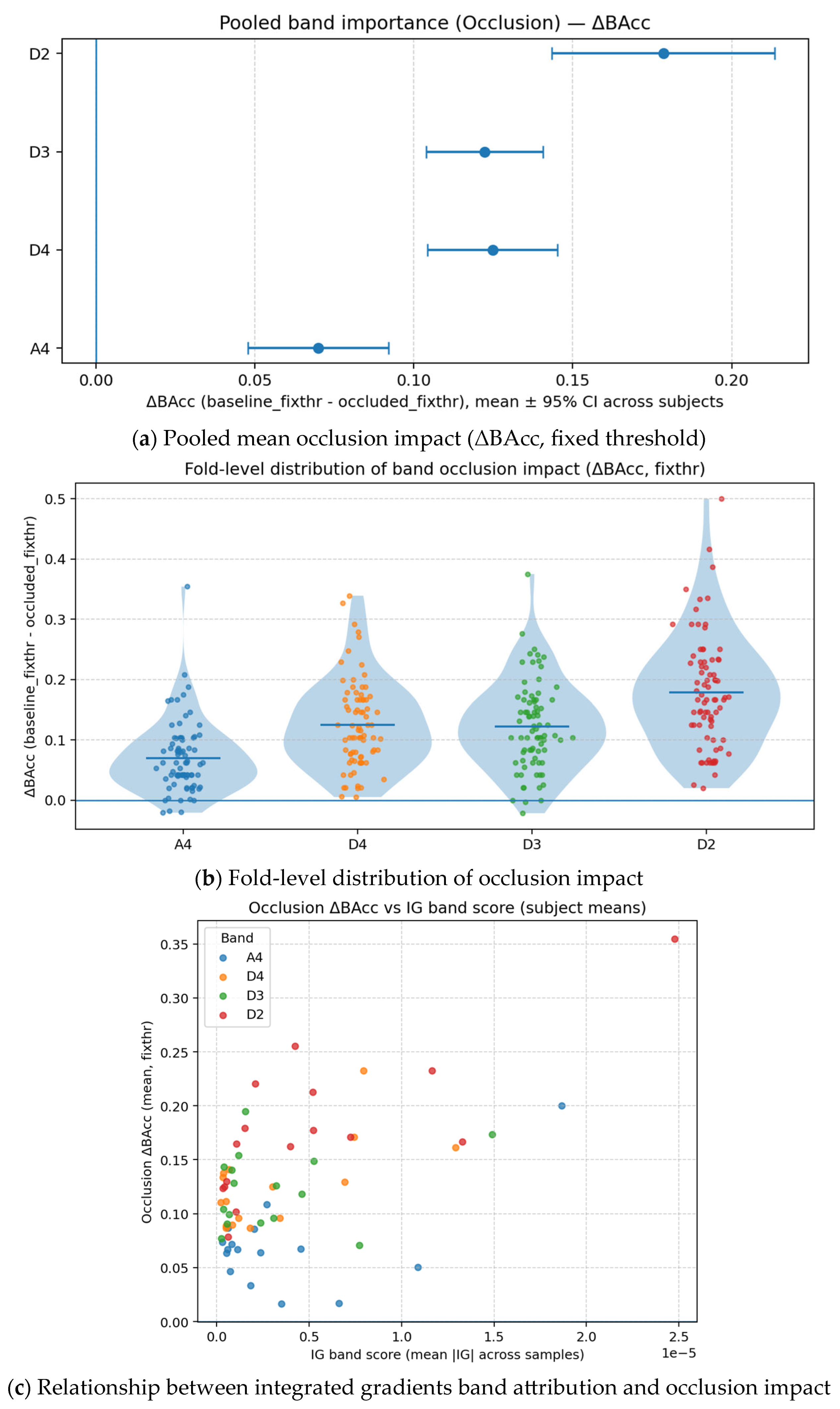

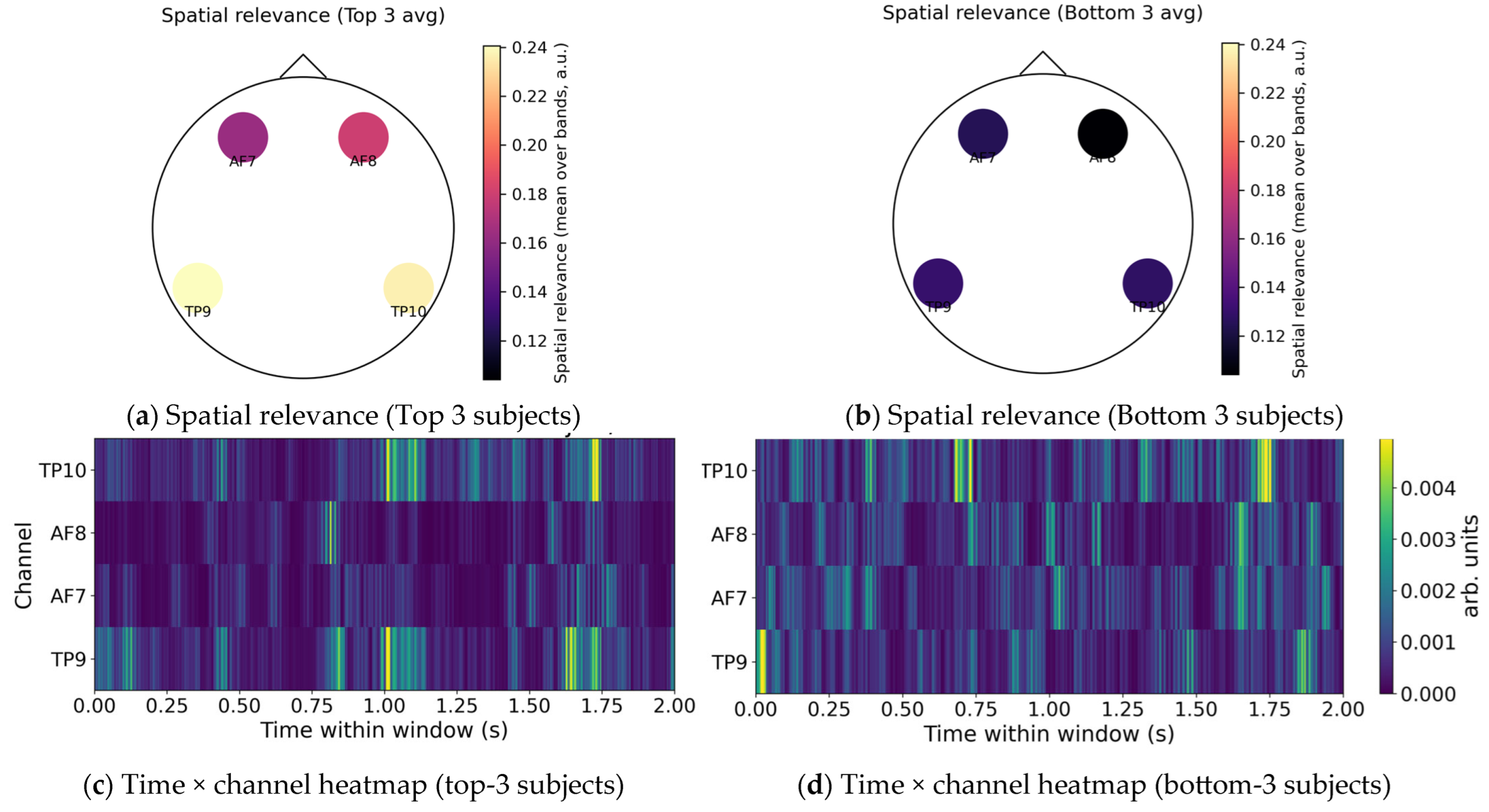

4.6. Explainability Analysis (Temporal, Spatial, and Spectral Relevancy)

4.7. Online System Evaluation

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Specification |

|---|---|

| CPU | AMD Ryzen 7 3700X 8-Core Processor @ 3.59 GHz |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Laptop GPU (12 GB VRAM) |

| RAM | 32 GB DDR4 |

| Operating System | Windows 11 Pro 22H2 (64-bit, Build 22,621.4317) |

| Driver/CUDA | NVIDIA Driver 560.94·CUDA 12.6 |

| Python | 3.10.16 (conda-forge distribution) |

| TensorFlow | 2.10.0 |

| NumPy | 1.26.4 |

| PyWavelets | 1.7.0 |

References

- Lopez-Gordo, M.A.; Sanchez-Morillo, D.; Valle, F.P. Dry EEG electrodes. Sensors 2014, 14, 12847–12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zeng, J.; Lin, S.; Wu, H. Flexible Electrodes for Non-Invasive Brain–Computer Interfaces: A Perspective. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 090901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigolson, O.E.; Williams, C.C.; Norton, A.; Hassall, C.D.; Colino, F.L. Choosing MUSE: Validation of a low-cost, portable EEG system for ERP research. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, H.B.; Magne, C. Exploring the utility of the muse headset for capturing the N400: Dependability and single-trial analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelinger, L.; Zhang, M.; Frohlich, F.; Daughters, S.B. Day-to-day individual alpha frequency variability measured by a mobile EEG device relates to anxiety. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2023, 57, 1815–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratti, E.; Waninger, S.; Berka, C.; Ruffini, G.; Verma, A. Comparison of medical and consumer wireless EEG systems for use in clinical trials. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikkai, A.; Dandekar, S.; E Curtis, C. Lateralization in alpha-band oscillations predicts the locus and spatial distribution of attention. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncompte, G.; Villena-González, M.; Cosmelli, D.; López, V. Spontaneous alpha power lateralization predicts detection performance in an un-cued signal detection task. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diepen, R.M.; Miller, L.M.; Mazaheri, A.; Geng, J.J. The role of alpha activity in spatial and feature-based attention. ENeuro 2016, 3, ENEURO.0204-16.2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desantis, A.; Chan-Hon-Tong, A.; Collins, T.; Hogendoorn, H.; Cavanagh, P. Decoding the temporal dynamics of covert spatial attention using multivariate EEG analysis: Contributions of raw amplitude and alpha power. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 570419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, T.; Lajnef, T.; Jerbi, K.; Arguin, M.; Aubin, M.; Jolicoeur, P. Decoding the locus of covert visuospatial attention from EEG signals. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shad, E.H.T.; Molinas, M.; Ytterdal, T. Impedance and noise of passive and active dry EEG electrodes: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 14565–14577. [Google Scholar]

- Kam, J.W.; Griffin, S.; Shen, A.; Patel, S.; Hinrichs, H.; Heinze, H.-J.; Deouell, L.Y.; Knight, R.T. Systematic comparison between a wireless EEG system with dry electrodes and a wired EEG system with wet electrodes. NeuroImage 2019, 184, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spüler, M. A high-speed brain-computer interface (BCI) using dry EEG electrodes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172400. [Google Scholar]

- Riccio, A.; Mattia, D.; Simione, L.; Olivetti, M.; Cincotti, F. Eye-gaze independent EEG-based brain–computer interfaces for communication. J. Neural Eng. 2012, 9, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treder, M.S.; Schmidt, N.M.; Blankertz, B. Gaze-independent brain–computer interfaces based on covert attention and feature attention. J. Neural Eng. 2011, 8, 066003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.-J.; Ferreria, V.Y.; Ulrich, D.; Kilic, T.; Chatziliadis, X.; Blankertz, B.; Treder, M. A gaze independent brain-computer interface based on visual stimulation through closed eyelids. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortkjær, J.; Wong, D.D.; Catania, A.; Märcher-Rørsted, J.; Ceolini, E.; Fuglsang, S.A.; Kiselev, I.; Di Liberto, G.; Liu, S.-C.; Dau, T. Real-time control of a hearing instrument with EEG-based attention decoding. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 016027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Power, S.D. k-fold cross-validation can significantly over-estimate true classification accuracy in common EEG-based passive BCI experimental designs: An empirical investigation. Sensors 2023, 23, 6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookshire, G.; Kasper, J.; Blauch, N.M.; Wu, Y.C.; Glatt, R.; Merrill, D.A.; Gerrol, S.; Yoder, K.J.; Quirk, C.; Lucero, C. Data leakage in deep learning studies of translational EEG. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1373515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Narayanan, A. Leakage and the reproducibility crisis in machine-learning-based science. Patterns 2023, 4, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrisson, E.; Jerbi, K. Exceeding chance level by chance: The caveat of theoretical chance levels in brain signal classification and statistical assessment of decoding accuracy. J. Neurosci. Methods 2015, 250, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K.H.; Ong, C.S.; Stephan, K.E.; Buhmann, J.M. The balanced accuracy and its posterior distribution. In Proceedings of the 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, 23–26 August 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 3121–3124. [Google Scholar]

- Scikit-Learn Developers. Balanced_Accuracy_Score: Compute the Balanced Accuracy. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.metrics.balanced_accuracy_score.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Gosala, B.; Kapgate, P.D.; Jain, P.; Chaurasia, R.N.; Gupta, M. Wavelet transforms for feature engineering in EEG data processing: An application on Schizophrenia. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104811. [Google Scholar]

- Lashgari, E.; Liang, D.; Maoz, U. Data augmentation for deep-learning-based electroencephalography. J. Neurosci. Methods 2020, 346, 108885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- George, O.; Smith, R.; Madiraju, P.; Yahyasoltani, N.; Ahamed, S.I. Data augmentation strategies for EEG-based motor imagery decoding. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banville, H.; Wood, S.U.; Aimone, C.; Engemann, D.-A.; Gramfort, A. Robust learning from corrupted EEG with dynamic spatial filtering. NeuroImage 2022, 251, 118994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthi, B.; Ng, S.-C.; Ezilarasan, M.; Leung, M.-F. EEG-based emotion recognition using hybrid CNN and LSTM classification. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1019776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, H.; Ono, K.; Panagiotis, A. Attention-Based PSO-LSTM for Emotion Estimation Using EEG. Sensors 2024, 24, 8174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, C.; Moreau, T.; Gramfort, A. CADDA: Class-wise automatic differentiable data augmentation for EEG signals. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.13695. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Li, L.; Dang, F.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y. A survey on edge computing for wearable technology. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 125, 103146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.A.; Mellinger, J.; Schalk, G.; Williams, J. A procedure for measuring latencies in brain–computer interfaces. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 1785–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaneh, M.; Ward, T.E.; Robertson, I.H. Effects of feedback latency on P300-based brain-computer interface. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2015, 2015, 2315–2318. [Google Scholar]

- Mwata-Velu, T.; Niyonsaba-Sebigunda, E.; Avina-Cervantes, J.G.; Ruiz-Pinales, J.; Velu-A-Gulenga, N.; Alonso-Ramírez, A.A. Motor Imagery Multi-Tasks Classification for BCIs Using the NVIDIA Jetson TX2 Board and the EEGNet Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Erp, J.; Lotte, F.; Tangermann, M. Brain-computer interfaces: Beyond medical applications. Computer 2012, 45, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Rivera, Y.; Cardona Álvarez, Y.; Gomez-Morales, O.; Alvarez-Meza, A.; Castellanos-Domínguez, G. BCI-based real-time processing for implementing deep learning frameworks using motor imagery paradigms. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2024, 22, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Alonso, L.F.; Gomez-Gil, J. Brain computer interfaces, a review. Sensors 2012, 12, 1211–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farwell, L.; Donchin, E. Talking off the top of your head: Toward a mental prosthesis utilizing event-related brain potentials. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1988, 70, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Chen, X.; Ban, N.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, H. Advances in P300 brain–computer interface spellers: Toward paradigm design and performance evaluation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1077717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wu, W.; Gao, X. Frequency recognition based on canonical correlation analysis for SSVEP-based BCIs. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 53, 2610–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Jung, T.-P.; Gao, X. Filter bank canonical correlation analysis for implementing a high-speed SSVEP-based brain–computer interface. J. Neural Eng. 2015, 12, 046008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.-T.; Gao, X.; Jung, T.-P. Enhancing detection of SSVEPs for a high-speed brain speller using task-related component analysis. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 65, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; He, D.; Li, C.; Qi, S. Brain–computer interface speller based on steady-state visual evoked potential: A review focusing on the stimulus paradigm and performance. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Han, C.; Jia, Y. Effects of mental load and fatigue on steady-state evoked potential based brain computer interface tasks: A comparison of periodic flickering and motion-reversal based visual attention. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diepen, R.M.; Foxe, J.J.; Mazaheri, A. The functional role of alpha-band activity in attentional processing: The current zeitgeist and future outlook. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 29, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ede, F.; Quinn, A.J.; Woolrich, M.W.; Nobre, A.C. Neural oscillations: Sustained rhythms or transient burst-events? Trends Neurosci. 2018, 41, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: A compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisotto, G.; Zanga, A.; Chlebus, J.; Zoppis, I.; Manzoni, S.; Markowska-Kaczmar, U. Comparison of attention-based deep learning models for eeg classification. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.01074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, M.; Van Velzen, J.; Eimer, M. The N2pc component and its links to attention shifts and spatially selective visual processing. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Z. Further evidence that N2pc reflects target enhancement rather than distracter suppression. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxe, J.J.; Snyder, A.C. The role of alpha-band brain oscillations as a sensory suppression mechanism during selective attention. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöstmann, M.; Alavash, M.; Obleser, J. Alpha oscillations in the human brain implement distractor suppression independent of target selection. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9797–9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Herbst, S.K.; Klatt, L.; Wöstmann, M. Target enhancement or distractor suppression? Functionally distinct alpha oscillations form the basis of attention. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 55, 3256–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banville, H.; Chehab, O.; Hyvärinen, A.; Engemann, D.-A.; Gramfort, A. Uncovering the structure of clinical EEG signals with self-supervised learning. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 046020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostas, D.; Aroca-Ouellette, S.; Rudzicz, F. BENDR: Using transformers and a contrastive self-supervised learning task to learn from massive amounts of EEG data. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 653659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, C.; Tellez Ceja, I.F.; Sweeney-Reed, C.M.; Heinze, H.-J.; Hinrichs, H.; Dürschmid, S. Impact of stimulus features on the performance of a gaze-independent brain-computer interface based on covert spatial attention shifts. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 591777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.; Ahn, M. P300 brain–computer interface-based drone control in virtual and augmented reality. Sensors 2021, 21, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFleur, K.; Cassady, K.; Doud, A.; Shades, K.; Rogin, E.; He, B. Quadcopter control in three-dimensional space using a noninvasive motor imagery-based brain–computer interface. J. Neural Eng. 2013, 10, 046003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prapas, G.; Angelidis, P.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Bibi, S.; Tsipouras, M.G. Connecting the brain with augmented reality: A systematic review of BCI-AR systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, D.; Saeed, M.; Husain Alhosani, M.; F. Al Wahedi, Y. Comparison of EEG Signal Spectral Characteristics Obtained with Consumer-and Research-Grade Devices. Sensors 2024, 24, 8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, H.; Scholz, M.; Baum, A.K.; Kam, J.W.Y.; Knight, R.T.; Heinze, H.-J. Comparison between a wireless dry electrode EEG system with a conventional wired wet electrode EEG system for clinical applications. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.K.; Chin, Z.Y.; Wang, C.; Guan, C.; Zhang, H. Filter bank common spatial pattern algorithm on BCI competition IV datasets 2a and 2b. Front. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barachant, A.; Bonnet, S.; Congedo, M.; Jutten, C. Multiclass brain–computer interface classification by Riemannian geometry. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 59, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, S.; Weng, S. CTNet: A convolutional transformer network for EEG-based motor imagery classification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-E.; Lee, S.-H. EEG-transformer: Self-attention from transformer architecture for decoding EEG of imagined speech. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th International Winter Conference on Brain-Computer Interface (BCI), Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea, 21–23 February 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Tan, H.; Duan, W. EEGformer: A transformer–based brain activity classification method using EEG signal. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1148855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaei, E.; Hosseini, M. Transformers in EEG Analysis: A review of architectures and applications in motor imagery, seizure, and emotion classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigdely-Shamlo, N.; Mullen, T.; Kothe, C.; Su, K.-M.; Robbins, K.A. The PREP pipeline: Standardized preprocessing for large-scale EEG analysis. Front. Neuroinform. 2015, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jas, M.; Engemann, D.A.; Bekhti, Y.; Raimondo, F.; Gramfort, A. Autoreject: Automated artifact rejection for MEG and EEG data. NeuroImage 2017, 159, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pion-Tonachini, L.; Kreutz-Delgado, K.; Makeig, S. ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage 2019, 198, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.L.; Monachino, A.D.; Morales, S.; Leach, S.C.; Bowers, M.E.; Gabard-Durnam, L.J. HAPPILEE: HAPPE In Low Electrode Electroencephalography, a standardized pre-processing software for lower density recordings. NeuroImage 2022, 260, 119390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.T.; Enticott, P.G.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Bailey, N.W. RELAX-Jr: An Automated Pre-Processing Pipeline for Developmental EEG Recordings. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2024, 45, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashi, A.G.; Azab, A.M.; Eldawlatly, S.; Aly, G.M. Generative adversarial networks in EEG analysis: An overview. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L.; Ding, X.; Lv, Y.; Qiu, S.; Liu, Q. Electroencephalographic signal data augmentation based on improved generative adversarial network. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Yan, B.; Tong, L.; Shu, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Zeng, Y. Data augmentation for EEG-based emotion recognition using generative adversarial networks. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 723843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, W.; Gu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Self-supervised learning for electroencephalogram: A systematic survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varoquaux, G. Cross-validation failure: Small sample sizes lead to large error bars. Neuroimage 2018, 180, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalabadi, H.; Alizadeh, S.; Schönauer, M.; Leibold, C.; Gais, S. Multivariate classification of neuroimaging data with nested subclasses: Biased accuracy and implications for hypothesis testing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InteraXon. Muse 2—EEG Headband Technical Specifications. Available online: https://choosemuse.com/products/muse-2 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Krigolson, O.E.; Hammerstrom, M.R.; Abimbola, W.; Trska, R.; Wright, B.W.; Hecker, K.G.; Binsted, G. Using Muse: Rapid mobile assessment of brain performance. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 634147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, T.S. Muse 2 Headband Specifications. Tecnológico de Monterrey. Available online: https://ifelldh.tec.mx/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Li, G.; Wang, S.; Duan, Y.Y. Towards gel-free electrodes: A systematic study of electrode-skin impedance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 241, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautan, A.-M.; Mihajlovic, V.; Chen, Y.-H.; Grundlehner, B.; Penders, J.; Serdijn, W. Signal quality in dry electrode EEG and the relation to skin-electrode contact impedance magnitude. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices (BIODEVICES 2014), ESEO, Angers, France, 3–6 March 2014; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2014; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, M.; Ahn, M. Evaluation of consumer-grade wireless EEG systems for brain-computer interface applications. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2024, 14, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InteraXon Inc. MuseLab (v1.9.5) [Software]. Available online: https://choosemuse.com/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Worden, M.S.; Foxe, J.J.; Wang, N.; Simpson, G.V. Anticipatory biasing of visuospatial attention indexed by retinotopically specific alpha-band electroencephalography increases over occipital cortex. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2000, 20, RC63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thut, G.; Nietzel, A.; Brandt, S.A.; Pascual-Leone, A. α-Band electroencephalographic activity over occipital cortex indexes visuospatial attention bias and predicts visual target detection. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 9494–9502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfurtscheller, G.; Da Silva, F.L. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: Basic principles. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuper, C.; Scherer, R.; Reiner, M.; Pfurtscheller, G. Imagery of motor actions: Differential effects of kinesthetic and visual–motor mode of imagery in single-trial EEG. Cogn. Brain Res. 2005, 25, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelstra, S.; Muhl, C.; Soleymani, M.; Lee, J.-S.; Yazdani, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Pun, T.; Nijholt, A.; Patras, I. Deap: A database for emotion analysis; using physiological signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2011, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.-L.; Lu, B.-L. Investigating critical frequency bands and channels for EEG-based emotion recognition with deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev. 2015, 7, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, B.Z.; Pineda, J.A. Effects of SOA and flash pattern manipulations on ERPs, performance, and preference: Implications for a BCI system. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2006, 59, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugi, M.; Hagimoto, Y.; Nambu, I.; Gonzalez, A.; Takei, Y.; Yano, S.; Hokari, H.; Wada, Y. Improving the performance of an auditory brain-computer interface using virtual sound sources by shortening stimulus onset asynchrony. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotte, F.; Larrue, F.; Mühl, C. Flaws in current human training protocols for spontaneous brain-computer interfaces: Lessons learned from instructional design. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, A.; Debener, S.; Gratton, G.; Junghöfer, M.; Kappenman, E.S.; Luck, S.J.; Luu, P.; Miller, G.A.; Yee, C.M. Committee report: Publication guidelines and recommendations for studies using electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography. Psychophysiology 2014, 51, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappenman, E.S.; Luck, S.J. Best practices for event-related potential research in clinical populations. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2016, 1, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, C.R.; Appelhoff, S.; Gorgolewski, K.J.; Flandin, G.; Phillips, C.; Delorme, A.; Oostenveld, R. EEG-BIDS, an extension to the brain imaging data structure for electroencephalography. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIDS Maintainers. The Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) Specification, v1.10+. Available online: https://bids-specification.readthedocs.io/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Chaumon, M.; Bishop, D.V.; Busch, N.A. A practical guide to the selection of independent components of the electroencephalogram for artifact correction. J. Neurosci. Methods 2015, 250, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaraswamy, S.D. High-frequency brain activity and muscle artifacts in MEG/EEG: A review and recommendations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmann, A.; Schröger, E.; Maess, B. Digital filter design for electrophysiological data—A practical approach. J. Neurosci. Methods 2015, 250, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SciPy Developers. signal.iirnotch—Notch Filter Design. Available online: https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.signal.iirnotch.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- SciPy Developers. signal.lfilter—IIR Filtering. Available online: https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.signal.lfilter.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- SciPy Developers. scipy.signal (Butter, Buttord, Sosfiltfilt). Available online: https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/signal.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Acunzo, D.J.; Mackenzie, G.; Van Rossum, M.C.W. Systematic biases in early ERP and ERF components as a result of high-pass filtering. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 209, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, D.; Morgan-Short, K.; Luck, S.J. How inappropriate high-pass filters can produce artifactual effects and incorrect conclusions in ERP studies of language and cognition. Psychophysiology 2015, 52, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramfort, A.; Luessi, M.; Larson, E.; Engemann, D.A.; Strohmeier, D.; Brodbeck, C.; Parkkonen, L.; Hämäläinen, M.S. MNE software for processing MEG and EEG data. Neuroimage 2014, 86, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999, 29, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.J. On the use of windows for harmonic analysis with the discrete Fourier transform. Proc. IEEE 2005, 66, 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.X. Analyzing Neural Time Series Data: Theory and Practice; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 2003, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SciPy Developers. signal.welch—Welch’s Method for PSD Estimation. Available online: https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.signal.welch.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Thorpe, S.; D’zMura, M.; Srinivasan, R. Lateralization of frequency-specific networks for covert spatial attention to auditory stimuli. Brain Topogr. 2012, 25, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.P.; MacKinnon, C.D. Time–frequency analysis of movement-related spectral power in EEG during repetitive move-ments: A comparison of methods. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 186, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moca, V.V.; Bârzan, H.; Nagy-Dăbâcan, A.; Mureșan, R.C. Time-frequency super-resolution with superlets. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, H.U.; Malik, A.S.; Ahmad, R.F.; Badruddin, N.; Kamel, N.; Hussain, M.; Chooi, W.-T. Feature extraction and classification for EEG signals using wavelet transform and machine learning techniques. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2015, 38, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Kong, X.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, L. Automatic detection of abnormal EEG signals using multiscale features with ensemble learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 943258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qazzaz, N.K.; Hamid Bin Mohd Ali, S.; Ahmad, S.A.; Islam, M.S.; Escudero, J. Selection of mother wavelet functions for multi-channel EEG signal analysis during a working memory task. Sensors 2015, 15, 29015–29035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutterer, D.W.; Polyn, S.M.; Woodman, G.F. α-Band activity tracks a two-dimensional spotlight of attention during spatial working memory maintenance. J. Neurophysiol. 2021, 125, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, T.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Anand, S. A comparative study of wavelet families for EEG signal classification. Neurocomputing 2011, 74, 3051–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Wallace, B.C. Attention is not explanation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.10186. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegreffe, S.; Pinter, Y. Attention is not not explanation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.04626. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liesaputra, V.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. An in-depth survey on deep learning-based motor imagery electroencephalogram (EEG) classification. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 147, 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; Noordhuis, P.; Wesolowski, L.; Kyrola, A.; Tulloch, A.; Jia, Y.; He, K. Accurate, large minibatch sgd: Training imagenet in 1 hour. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02677. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [Google Scholar]

- Pascanu, R.; Mikolov, T.; Bengio, Y. On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. PMLR 2013, 28, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Youden, W.J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950, 3, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.S.; Chan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chiu, C.-C.; Zoph, B.; Cubuk, E.D.; Le, Q.V. Specaugment: A simple data augmentation method for automatic speech recognition. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.08779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, B. The student-teacher framework guided by self-training and consistency regularization for semi-supervised medical image segmentation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, E0300039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarvainen, A.; Valpola, H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cisse, M.; Dauphin, Y.N.; Lopez-Paz, D. mixup: Beyond empirical risk minimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.09412. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.; Han, D.; Oh, S.J.; Chun, S.; Choe, J.; Yoo, Y. Cutmix: Regularization strategy to train strong classifiers with localizable features. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 6023–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varoquaux, G.; Raamana, P.R.; Engemann, D.A.; Hoyos-Idrobo, A.; Schwartz, Y.; Thirion, B. Assessing and tuning brain decoders: Cross-validation, caveats, and guidelines. NeuroImage 2017, 145, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thölke, P.; Mantilla-Ramos, Y.-J.; Abdelhedi, H.; Maschke, C.; Dehgan, A.; Harel, Y.; Kemtur, A.; Berrada, L.M.; Sahraoui, M.; Young, T. Class imbalance should not throw you off balance: Choosing the right classifiers and performance metrics for brain decoding with imbalanced data. NeuroImage 2023, 277, 120253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, H.; Kim, D.M.; Gong, T.; Chung, H.W.; Lee, S.-J. SNAP-TTA: Sparse Test-Time Adaptation for Latency-Sensitive Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.15276. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, K.Q. On calibration of modern neural networks. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. PMLR 2017, 70, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.; Munafò, M.R. Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpow, J.; Birbaumer, N.; McFarland, D.J.; Pfurtscheller, G.; Vaughan, T. Brain-computer interfaces for communication and control. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 767–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadra, J.G.; Bengson, J.J.; Morales, A.B.; Mangun, G.R. Attention without constraint: Alpha lateralization in uncued willed attention. Eneuro 2023, 10, ENEURO.0258-22.2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.J.; Awh, E. The role of alpha oscillations in spatial attention: Limited evidence for a suppression account. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 29, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhif, M.; Ben Abbes, A.; Farah, I.R.; Martínez, B.; Sang, Y. Wavelet transform application for/in non-stationary time-series analysis: A review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fahoum, A.S.; Al-Fraihat, A.A. Methods of EEG signal features extraction using linear analysis in frequency and time-frequency domains. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, 730218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, T.; Haller, M.; Peterson, E.J.; Varma, P.; Sebastian, P.; Gao, R.; Noto, T.; Lara, A.H.; Wallis, J.D.; Knight, R.T. Parameterizing neural power spectra into periodic and aperiodic components. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, R.A.; Alexander, N.; Maguire, E.A. Robust estimation of 1/f activity improves oscillatory burst detection. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 56, 5836–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, C.; Paillard, J.; Moreau, T.; Gramfort, A. Data augmentation for learning predictive models on EEG: A systematic comparison. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 066020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Sarna, A.; Tian, Y.; Isola, P.; Maschinot, A.; Liu, C.; Krishnan, D. Supervised contrastive learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 18661–18673. [Google Scholar]

- Keras Team. ReduceLROnPlateau (Callbacks API), v2.16.1. 2025. Available online: https://keras.io/api/callbacks/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Clements, J.; Sellers, E.; Ryan, D.; Caves, K.; Collins, L.; Throckmorton, C. Applying dynamic data collection to improve dry electrode system performance for a P300-based brain–computer interface. J. Neural Eng. 2016, 13, 066018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjan, D.; Gramann, K.; De Pauw, K.; Marusic, U. Removal of movement-induced EEG artifacts: Current state of the art and guidelines. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Lin, Y.-P. Movement artifact suppression in wearable low-density and dry eeg recordings using active electrodes and artifact subspace reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 3844–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwidge, P.S.; McPherson, C.N.; Faulkenberg, L.; Morgan, A.; Baylis, G.C. A comparison of approaches for motion artifact removal from wireless mobile EEG during overground running. Sensors 2025, 25, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravichandran, V.; Ciesielska-Wrobel, I.; Rumon, M.A.A.; Solanki, D.; Mankodiya, K. Characterizing the impedance properties of dry e-textile electrodes based on contact force and perspiration. Biosensors 2023, 13, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotte, F.; Bougrain, L.; Cichocki, A.; Clerc, M.; Congedo, M.; Rakotomamonjy, A.; Yger, F. A review of classification algorithms for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces: A 10 year update. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A. Fourier-, Hilbert-and wavelet-based signal analysis: Are they really different approaches? J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 137, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frikha, T.; Abdennour, N.; Chaabane, F.; Ghorbel, O.; Ayedi, R.; Shahin, O.R.; Cheikhrouhou, O. Source Localization of EEG Brainwaves Activities via Mother Wavelets Families for SWT Decomposition. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9938646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaram, V.; Alamgir, M.; Altun, Y.; Scholkopf, B.; Grosse-Wentrup, M. Transfer learning in brain-computer interfaces. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2016, 11, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuper, C.; Pfurtscheller, G. Event-related dynamics of cortical rhythms: Frequency-specific features and functional correlates. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2001, 43, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Wang, C.-H.; Jung, T.-P.; Wu, T.-L.; Jeng, S.-K.; Duann, J.-R.; Chen, J.-H. EEG-based emotion recognition in music listening. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcao, S.M.; Fonseca, M.J. Emotions recognition using EEG signals: A survey. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2017, 10, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Song, D.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Hu, B. Exploring EEG features in cross-subject emotion recognition. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder, M.S.; Blankertz, B. (C) overt attention and visual speller design in an ERP-based brain-computer interface. Behav. Brain Funct. 2010, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimer, M. The N2pc component as an indicator of attentional selectivity. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 99, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuval-Greenberg, S.; Merriam, E.P.; Heeger, D.J. Spontaneous microsaccades reflect shifts in covert attention. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 13693–13700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielen, J.; Bosch, S.E.; Van Leeuwen, T.M.; Van Gerven, M.A.J.; Van Lier, R. Evidence for confounding eye movements under attempted fixation and active viewing in cognitive neuroscience. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafed, Z.M.; Clark, J.J. Microsaccades as an overt measure of covert attention shifts. Vis. Res. 2002, 42, 2533–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Y.; Li, P.; Gao, Z.; Shen, M. Microsaccades reflect attention shifts: A mini review of 20 years of microsaccade research. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1364939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; Lu, B.-L. Transfer Learning for EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Review of Progress Made Since 2016. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2020, 14, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wu, D. Transfer Learning for Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Euclidean Space Data Alignment Approach. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, P.; Congedo, M.; Jutten, C.; Said, S.; Berthoumieu, Y. Transfer learning: A Riemannian geometry framework with applications to brain-computer interfaces. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 65, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ma, Z.; Meng, J.; Xu, M.; Jung, T.-P.; Ming, D. Improving Transfer Performance of Deep Learning with Adaptive Batch Normalization for Brain-computer Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 5800–5803. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, A.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Long, J. Subject adaptation convolutional neural network for EEG-based motor imagery classification. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 066003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.K. On optimum recognition error and reject tradeoff. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1970, 16, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Yaniv, R.; Wiener, Y. On the Foundations of Noise-free Selective Classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 1605–1641. [Google Scholar]

| Block | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| CV | val_fraction | 0.25 |

| test_fraction | 0.2 | |

| n_repeats | 5 | |

| random_state | 42 | |

| Training | epochs | 300 |

| batch_size | 64 | |

| learning rate | 0.0002 | |

| L2 penalty | 0.0001 | |

| label smoothing | 0.02 | |

| mixup/mixup_alpha | true/0.2 | |

| Feature | fs | 256 |

| window/step | 512/256 | |

| Augment | noise_std | 0.005 |

| drop_p | 0.15 | |

| shift_max | 0.05 |

| Model (Decoder) | Trainable Params | CPU Forward (ms) | GPU Forward (ms) | Total est. Latency (ms) | Online Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN (EEG-specific compact CNN) | 34,689 | 4.873 | 3.857 | 2028.9 | 0.578 |

| CNN + LSTM | 67,713 | 170.126 | 8.148 | 2033.1 | 0.612 |

| Hybrid (CNN + LSTM + MHSA), All-off-Wav | 84,353 | 184.705 | 10.863 | 2035.9 | 0.673 |

| Hybrid (CNN + LSTM + MHSA), All-on-Wav | 84,353 | 184.705 | 10.863 | 2035.9 | 0.695 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Lee, J. Robust Covert Spatial Attention Decoding from Low-Channel Dry EEG by Hybrid AI Model. AI 2026, 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010009

Kim D, Lee J. Robust Covert Spatial Attention Decoding from Low-Channel Dry EEG by Hybrid AI Model. AI. 2026; 7(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Doyeon, and Jaeho Lee. 2026. "Robust Covert Spatial Attention Decoding from Low-Channel Dry EEG by Hybrid AI Model" AI 7, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010009

APA StyleKim, D., & Lee, J. (2026). Robust Covert Spatial Attention Decoding from Low-Channel Dry EEG by Hybrid AI Model. AI, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010009