The Current Landscape of Automatic Radiology Report Generation with Deep Learning: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

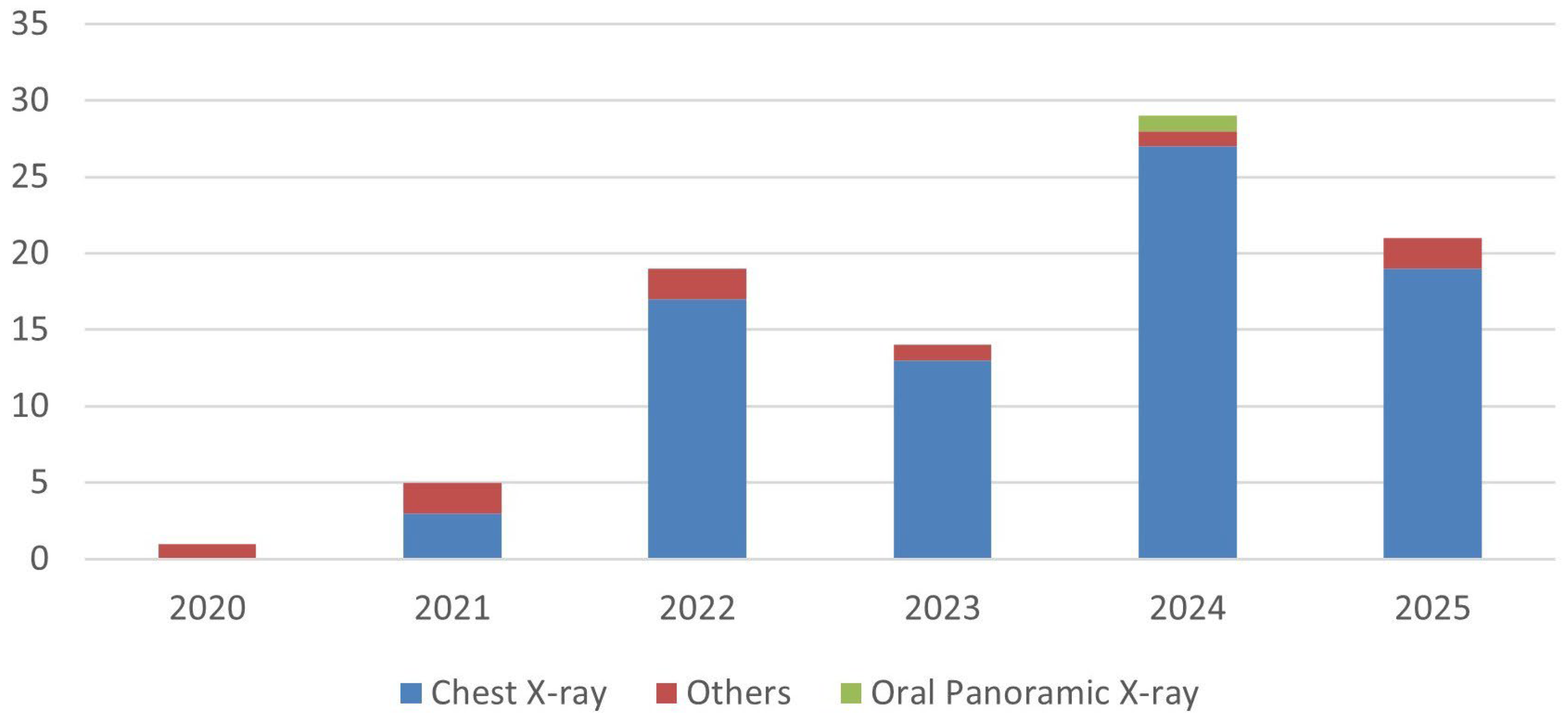

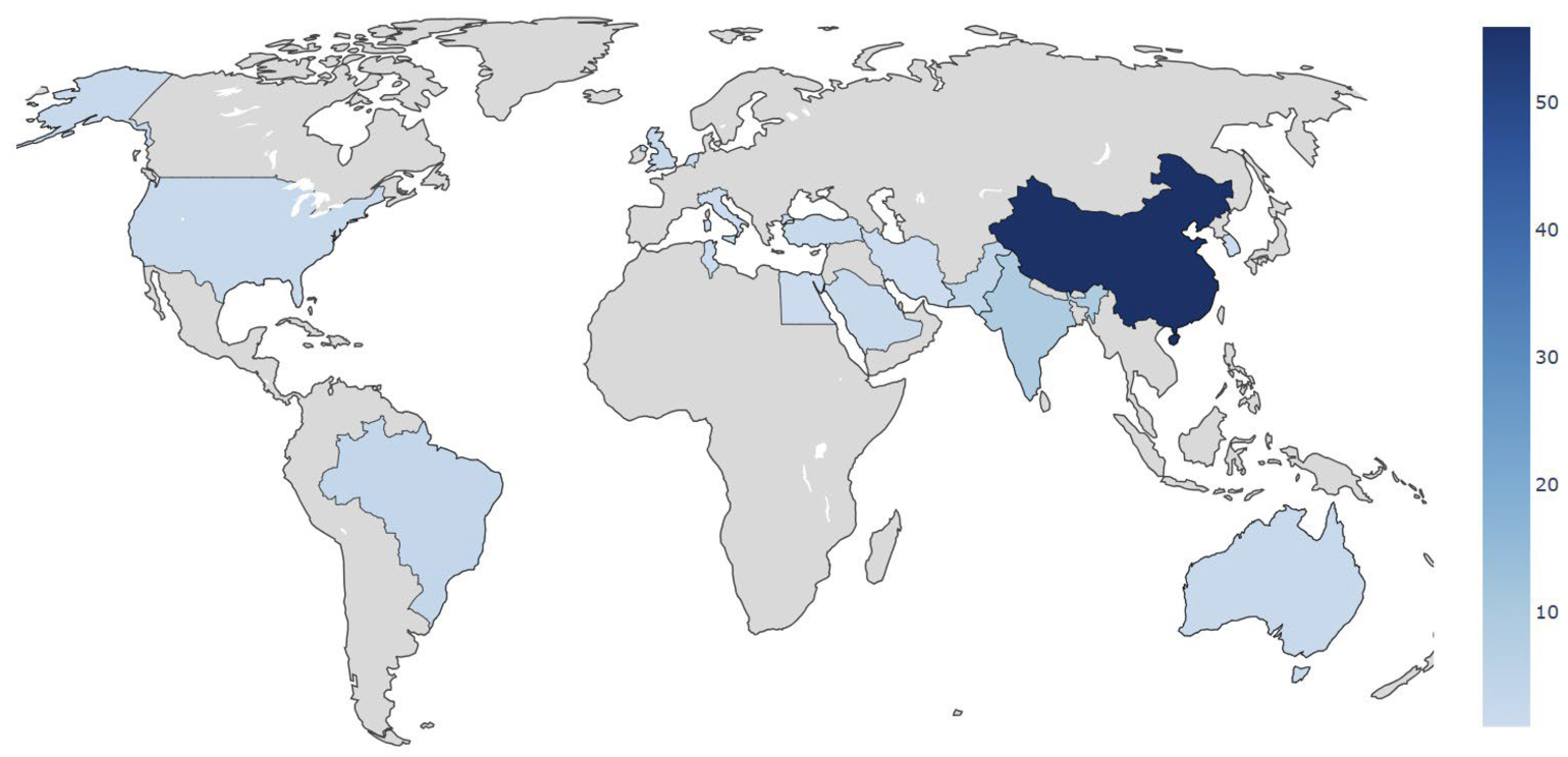

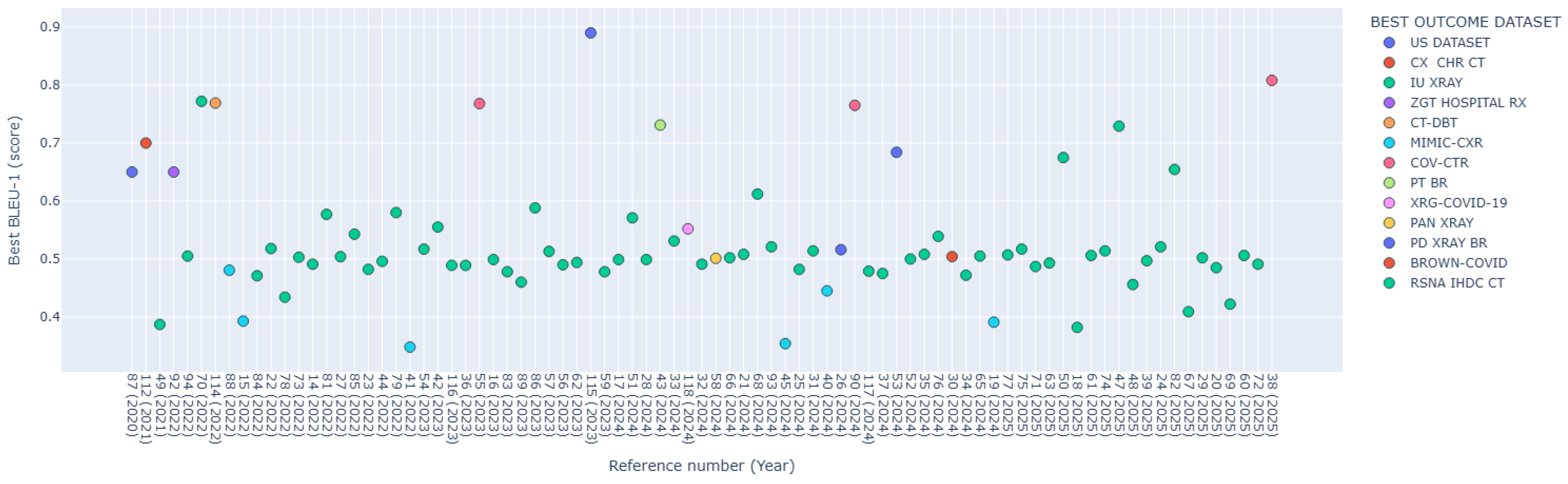

3. Results

3.1. CNN + Transformers

3.2. Transformers

3.3. Multihybrid

3.4. CNN + RNN Architectures

3.5. Others

| Year | Refs. | Radiological Domain | Datasets (DS) Used | Deep Learning Method | Architecture | Best BLEU-1 | Best Outcome DS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Zeng X. et al. [86] | Ultrasound (US) (gallbladder, kidney, liver), Chest X-ray | US image dataset (6563 images). IU-Xray (7470 images, 3955 reports) | CNN, RNN | SFNet (Semantic fusion network). ResNet-50. Faster RCNN. Diagnostic report generation module using LSTM | 0.65 | US DATASET |

| 2021 | Liu G. et al. [94] | Chest CT | COVID-19 CT dataset (368 reports, 1104 CT images). CX-CHR dataset (45,598 images, 28,299 reports), 12 million external medical textbooks | Transformer, CNN | Medical-VLBERT (with DenseNet-121 as backbone) | 0.70 | CX CHR CT |

| 2021 | Alfarghaly O. et al. [49] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | Transformer | 2 CDGPT2 (Conditioned Distil Generative Pre-trained Transformer) | 0.387 | IU-Xray |

| 2021 | Moon J.H. et al. [95] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR (377,110 images, 227,835 reports). IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | BERT-base | * 0.126 (BLEU-4) | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2021 | Loveymi S. et al. [91] | Liver CT | Liver CT annotation dataset from ImageCLEF 2015 (50 patients) | CNN | MobileNet-V2 | 0.65 | ZGT HOSPITAL RX |

| 2021 | Hou D. et al. [79] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, GAN | Encoder with two branches (CNN based on ResNet-152 and MLC). Hierarchical LSTM decoder with multi-level attention and a reward module with two discriminators. | * 0.148 (BLEU-4) | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2022 | Paalvast O. et al. [90] | Proximal Femur Fractures (X-ray) | Primary dataset: 4915 cases with 11,606 images and reports. Language model dataset: 28,329 radiological reports | CNN, RNN | DenseNet-169 for classification. Encoder–Decoder for report generation. GloVe for language modeling | 0.65 | MAIN DATASET |

| 2022 | Zhang D. et al. [93] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | GNN, Transformer | Custom framework using Transformer for the generation module | 0.505 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Kaur. N. et al. [69] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | CNN VGG19 network (feature extraction). BERT (language generation). DistilBERT (perform sentiment) | 0.772 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Aswiga R. et al. [96] | Liver CT and kidney, DBT (Digital Breast Tomosynthesis) | ImageNet (25,000 images). CT abdomen and mammography images (750 images). CT and DBT medical images (150 images) | RNN, CNN | MLTL-LSTM model (Multi-level transfer learning framework with a long short-term-memory model) | 0.769 | CT-DBT |

| 2022 | Xu Z. et al. [87] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | HReMRG-MR (Hybrid reinforced report generation method with m-linear attention and repetition penalty mechanism) | 0.4806 | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2022 | Nicolson A. et al. [15] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | CvT2DistilGPT2 | 0.4732 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Yan S. et al. [64] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | DenseNet (encoder). LSTM or Transformer (decoder). ATAG (Attributed abnormality graph) embeddings. GATE (gating mechanism) | ** 0.323 (BLEU AVG) | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Gajbhiye G.O. et al. [8] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | AMLMA (Adaptive multilevel multi-attention) | 0.471 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Shang C. et al. [22] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | MATNet (Multimodal adaptive transformer) | 0.518 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Li H. et al. [77] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Attention Mechanism | RCLN model (combining CNN, LSTM, and multihead attention mechanism). Pre-trained ResNet-152 (image encoder) | 0.4341 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Najdenkoska I. et al. [72] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | VTI (Variational topic inference) with LSTM-based and Transformer-based decoders | 0.503 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Yang Y. et al. [14] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | CTN built on Transformer architecture | 0.491 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Kaur N. et al. [80] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Reinforcement Learning | CADxReport (VGG19, HLSTM with co-attention mechanism and reinforcement learning) | 0.577 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Wang J. et al. [27] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | CAMANet (Class activation map guided attention network) | 0.504 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Kaur N. et al. [84] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Attention Mechanism | CheXPrune (encoder–decoder architecture with VGG19 and hierarchical LSTM) | 0.5428 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Yan B. et al. [23] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer, VAE | Prior Guided Transformer. ResNet101 (visual feature extractor). Vanilla Transformer (baseline) | 0.482 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Wang Z. et al. [44] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | Pure Transformer-based Framework (custom architecture) | 0.496 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Sirshar M. et al. [78] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | VGG16 (visual geometry group CNN). LSTM with attention | 0.580 | IU-Xray |

| 2022 | Vendrow & Schonfeld [41] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. CheXpert | Transformer | Meshed-memory augmented transformer architecture with visual extractor using ImageNet and CheXpert pre-trained weights | 0.348 | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2023 | Wang R. et al. [54] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | MFOT (Multi-feature optimization transformer) | 0.517 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Mohsan M.M. et al. [42] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | Transformer | TrMRG (Transformer Medical Report Generator) using ViT as encoder, MiniLM as decoder | 0.5551 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Xue Y. et al. [97] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer, CNN, RNN | ASGMD (Auxiliary signal guidance and memory-driven) network. ResNet-101 and ResNet-152 as visual feature extractors | 0.489 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Zhang S. et al. [36] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | Visual Prior-based Cross-modal Alignment Network | 0.489 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Zhang J. et al. [55] | Chest X-ray, CT COVID-19 | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray. COV-CTR (728 images) | Transformer | ICT (Information calibrated transformer) | 0.768 | COV-CTR |

| 2023 | Pan R. et al. [16] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer, Self-Supervised Learning | S3-Net (Self-supervised dual-stream network) | 0.499 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Yang Y. et al. [82] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | TriNet (custom architecture) | 0.478 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Gu Y. et al. [88] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray. Chexpert (224,316 images) | CNN, RNN | ResNet50. CVAM + MVSL (Cross-view attention module and Medical visual-semantic LSTMs) | 0.460 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Shetty S. et al. [85] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | Encoder–Decoder framework with UM-VES and UM-TES subnetworks and LSTM decoder | 0.5881 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Zhao G. et al. [57] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | ResNet101 (visual extractor). 3-layer Transformer structure (encoder–decoder framework). BLIP architecture | 0.513 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Hou X. et al. [56] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | Transformer, Contrastive Learning | MKCL (Medical knowledge with contrastive learning). ResNet-101. Transformer | 0.490 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Xu D. et al. [62] | Chest X-ray, Dermoscopy | IU-Xray, NCRC-DS (81 entities, 536 triples) | CNN, RNN, Transformer | DenseNet-121. ResNet-101. Memory-driven Transformer | 0.494 | IU-Xray |

| 2023 | Zeng X. et al. [98] | US (gallbladder, fetal heart), Chest X-ray | US dataset (6563 images and reports). Fetal Heart (FH) dataset (3300 images and reports). MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | AERMNet (Attention-Enhanced Relational Memory Network) | 0.890 | US DATASET |

| 2023 | Guo K. et al. [59] | Chest X-ray | NIH Chest X-ray (112,120 images). MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | ViT. GNN. Vector Retrieval Library. Multi-label contrastive learning. Multi-task learning | 0.478 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Pan Y. et al. [17] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | Swin-Transformer | 0.499 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Raminedi S. et al. [51] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | Transformer | ViGPT2 model | 0.571 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Liu Z. et al. [28] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | FMVP (Flexible multi-view paradigm) | 0.499 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Veras Magalhaes G. et al. [43] | Chest X-ray | Proposed Dataset (21,970 images). IU-Xray. NIH Chest X-ray | Transformer | XRaySwinGen (Swin Transformer as image encoder, GPT-2 as textual decoder) | 0.731 | PT BR |

| 2024 | Sharma D. et al. [33] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | FDT-Dr 2 T (custom framework) | 0.531 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Tang Y. et al. [99] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray. XRG-COVID-19 (8676 scans, 8676 reports) | CNN, Transformer | DSA-Transformer with ResNet-101 as the backbone | 0.552 | XRG-COVID-19 |

| 2024 | Li H. et al. [32] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | DenseNet-121. Transformer encoder. GPT-4 | 0.491 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Gao N. et al. [58] | Oral Panoramic X-ray | Oral panoramic X-ray image-report dataset (562 sets of images and reports). MIMIC-CXR | Transformer | MLAT (Multi-Level objective Alignment Transformer) | 0.5011 | PAN XRAY |

| 2024 | Yang B. et al. [66] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | MRARGN (Multifocal Region-Assisted Report Generation Network) | 0.502 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Liu X. et al. [21] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | Memory-driven Transformer (based on standard Transformer architecture with relational memory added to the decoder) | 0.508 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Alotaibi F.S. et al. [67] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | VGG19 (CNN) pre-trained over the ImageNet dataset. GloVe, fastText, ElMo, and BERT (extract textual features from the ground truth reports). Hierarchical LSTM (generate reports) | 0.612 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Sun S. et al. [92] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | RNN, Transformer, MLP | Transformer (encoder). MIX-MLP multi-label classification network. CAM (Co-attention mechanism) based on POS-SCAN. Hierarchical LSTM (decoder) | 0.521 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Zeiser F.A., et al. [45] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR | Transformer | CheXReport (Swin-B fully transformer) | 0.354 | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2024 | Zhang K. et al. [25] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | RAMT (Relation-Aware Mean Teacher). GHFE (Graph-guided hybrid feature encoding) module. DenseNet121 (visual feature extractor). Standard Transformer (decoder) | 0.482 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Li S. et al. [31] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | ResNet-101. Transformer (multilayer encoder and decoder) | 0.514 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Zheng Z. et al. [40] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | Team Role Interaction Network (TRINet) | 0.445 | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2024 | Vieira P.D.A. et al. [26] | Polydactyly X-ray | Custom dataset (16,710 images and reports) | CNN, Transformer | Inception-V3 CNN. Transformer Architecture | 0.516 | PD XRAY BR |

| 2024 | Leonardi G. et al. [46] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR | Transformer | ViT. GPT-2 (with custom positional encoding and beam search) | * 0.095 (BLEU-4) | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2024 | Zhang J. et al. [89] | Chest X-ray, Chest CT (COVID-19) | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray. COV-CTR | CNN, RNN | HDGAN (Hybrid Discriminator Generative Adversarial Network) | 0.765 | COV-CTR |

| 2024 | Alqahtani F. F. et al. [100] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray. Custom dataset (1250 images and reports) | CNN–Transformer | CNX-B2 (CNN encoder, BioBERT transformer) | 0.479 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Shahzadi I. et al. [37] | Chest X-ray | NIH ChestX-ray. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | CSAMDT (Conditional self-attention memory-driven transformer) | 0.504 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Xu L. et al. [53] | Ultrasound (gallbladder, kidney, liver), Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray. LGK US (6563 images and reports). | Transformer | CGFTrans (Cross-modal global feature fusion transformer) | 0.684 | US DATASET |

| 2024 | Yi X. et al. [52] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | TSGET (Two-stage global enhanced transformer) | 0.500 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Zhang W. et al. [35] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | VCIN (Visual-textual cross-modal interaction network). ACIE (Abundant clinical information embedding). Bert-based Decoder-only Generator | 0.508 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Yi X. et al. [75] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | Memory-driven Transformer | 0.539 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Zhong Z. et al. [30] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. Chest ImaGenome (237,853 images). Brown-COVID (1021 images). Penn-COVID (2879 images) | CNN, Transformer | MRANet (Multi-modality regional alignment network) | 0.504 | BROWN-COVID |

| 2024 | Liu A. et al. [34] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | ResNet-101. Multilayer Transformer (encoder and decoder) | 0.472 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Ran R. et al. [65] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | MeFD-Net (proposed multi-expert diagnostic module). ResNet101 (visual encoder). Transformer (text generation module) | 0.505 | IU-Xray |

| 2024 | Zhang K. et al. [19] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. Chest ImaGenome (242,072 scene graphs) | CNN, Transformer | Faster R-CNN (object detection). GPT-2 Medium (report generation) | 0.391 | MIMIC-CXR |

| 2025 | Zhu D. et al. [76] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | Denoising multi-level cross-attention. Contrastive learning model (with ViTs-B/16 as visual extractor, BERT as text encoder) | 0.507 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Huang L. et al. [74] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | KCAP (Knowledge-guided cross-modal alignment and progressive fusion) | 0.517 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Mei X. et al. [70] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer, ViT | ATL-CA (Adaptive topic learning and fine-grained crossmodal alignment) | 0.487 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Liu Y. et al. [63] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | ADCNet (Anomaly-driven cross-modal contrastive network). ResNet-101 and Transformer encoder–decoder architecture | 0.493 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Singh P. et al. [50] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | Transformer | ChestX-Transcribe (combines Swin Transformer and DistilGPT) | 0.675 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Bouslimi R. et al. [18] | Brain CT and MRI scans | RSNA-IHDC dataset (674,258 brain CT images, 19,530 patients) | CNN, Transformer | AC-BiFPN (Augmented convolutional bi-directional feature pyramid network). Transformer model | 0.382 | RSNA IHDC CT |

| 2025 | Dong Z. et al. [61] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | DCTMN (Dual-channel transmodal memory network) | 0.506 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Zhang J. et al. [73] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer, Graph Reasoning Network (GRN), Cross-modal Gated Fusion Network (CGFN) | ResNet101 (visual feature extraction). GRN. CGFN (Cross-modal gated fusion network). Transformer (decoder) | 0.514 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Batool H. et al. [47] | Spine CT | VerSe20 (300 MDCT spine images) | Transformer | ViT-Base. BioBERT BASE. MiniLM | 0.7291 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Zhao J. et al. [48] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | Transformer | ResNet-101 with CBAM (convolutional block attention module). Cross-attention mechanism | 0.456 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Fang J. et al. [39] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | MMG (Multi-modal granularity feature fusion) | 0.497 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Ho, X. et al. [24] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | RCAN (Recalibrated cross-modal alignment network) | 0.521 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Ucan M. et al. [81] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray | CNN, RNN | G-CNX (hybrid encoder–decoder architecture). ConvNeXtBase (encoder side). GRU-based RNN (decoder side) | 0.6544 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Yang B. et al. [66] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, RNN, Transformer | DPN (Dynamics priori networks) with components including DGN (Dynamic graph networks), Contrastive learning, and PrKN (Prior knowledge networks). ResNet-152 (image feature extraction). SciBert (report embedding) | 0.409 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Yu T. et al. [29] | Chest X-ray, Bladder Pathology | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray. 4253 bladder Pathology images. | Transformer, CNN | AHP (Adapter-enhanced hierarchical cross-modal pre-training) | 0.502 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Liu F. et al. [101] | Chest X-ray | COVIDx-CXR-2 (29,986 images). COVID-CXR (more than 900 images). BIMCV-COVID-19 (more than 10,000 images). COV-CTR. MIMIC-CXR. NIH ChestX-ray | CNN, Transformer | ResNet-50 (image encoder). BERT (text encoder). Transformer-based model (with variants using LLAMA-2-7B and Transformer-BASE, decoder) | * 0.63 (BLEU-4) | COVID-19 DATASETS |

| 2025 | Liu X. et al. [20] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | CNN, Transformer | CECL (Clustering enhanced contrastive learning) | 0.485 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Sun S. et al. [68] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Diffusion Models, RNN, CNN, Transformer | Diffusion Model-based architecture. ResNet34. Transformer structure using cross-attention | 0.422 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Yang Y. et al. [60] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. IU-Xray | Transformer | STREAM (Spatio-temporal and retrieval-augmented modeling). SwinTransformer (Swin-Base) (encoder). TinyLlama-1.1B (decoder). | 0.506 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Tang Y. et al. [71] | Chest X-ray | MIMIC-CXR. ROCO (over 81,000 images) | CNN, RNN, Transformer | CAT (Cross-modal augmented transformer) | 0.491 | IU-Xray |

| 2025 | Varol Arısoy M. et al. [38] | Chest X-ray | IU-Xray. COV-CTR | Transformer | MedVAG (Medical vision attention generation) | 0.808 | COV-CTR |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The field remains heavily concentrated on chest radiography, with more than 87% of studies based on CXR datasets. This reflects the availability of public data and the acceleration of thoracic imaging research during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also exposes a lack of anatomical diversity that limits generalizability to other diagnostic domains encountered in routine radiological practice.

- Hybrid architectures, particularly CNN–Transformer combinations, represent the dominant methodological trend (73% of included studies). By leveraging CNNs for localized visual encoding and Transformer modules for contextual reasoning, these models generate reports with greater coherence and better representation of abnormality, reducing variability and supporting more consistent documentation.

- The increased use of memory modules, medical knowledge graphs, and cross-modal alignment mechanisms demonstrates a clear shift toward clinically informed modeling. These strategies improve factual grounding by embedding structured domain knowledge into the generation process and aligning outputs more closely with expert reasoning.

- However, current evaluation frameworks remain poorly aligned with clinical decision-making. Metrics such as BLEU and ROUGE capture surface-level similarity but do not reflect diagnostic adequacy or patient management utility, underscoring the need for evaluation standards that measure whether generated reports truly support radiological interpretation and workflow reliability.

- Overall, ARRG has achieved meaningful technical progress, yet its translation into real clinical environments remains constrained by limited anatomical coverage, shallow evaluation standards, and insufficient external validation. For these systems to evolve from experimental prototypes into trustworthy decision support tools, future research must prioritize clinically grounded benchmarking, greater dataset diversity, and integration pathways that reflect the realities of radiological practice. As these gaps are progressively addressed, ARRG has the potential to become a scalable, clinically accountable complement to radiological reporting, provided that future developments successfully bridge the remaining clinical-readiness gap. By adopting a scoping review approach, this study offers a descriptive synthesis that can guide future systematic or meta-analytic investigations addressing specific diagnostic or methodological questions.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARRG | Automatic Radiology Report Generation |

| DL | Deep learning |

| PRISMA | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CNNs | Convolutional neural networks |

| RNNs | Recurrent neural networks |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| CLIP | Contrastive language-image pretraining |

| LLMs | Large language models |

| MIMIC | Medical information mart for intensive care database |

| MIMIC-CXR | MIMIC-Chest X-ray |

| IU-Xray | Indiana University Chest X-ray collection |

| BLEU | Bilingual evaluation understudy |

| ROUGE | Recall-oriented understudy for gisting evaluation |

| BERT | Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| IEEE | Institute of electrical and electronics engineers |

| ACM | Association for Computing Machinery |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| GNNs | Graph neural networks |

| GAT | Graph attention network |

| TRIPOD | Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis |

| CXR | Chest X-ray |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| CTN | Contrastive triplet network |

| SOTA | State of the art |

| METEOR | Metric for evaluation of translation with explicit ordering |

| CIDEr | Consensus-based image description evaluation |

| ViT | Vision transformers |

| GPT | Generative pre-trained transformers |

| NLG | Natural language generation |

| GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| SVMs | Support vector machines |

| KG | Knowledge graph |

| DS | Dataset |

| US | Ultrasound |

| DBT | Digital breast tomosynthesis |

| SFNet | Semantic fusion network |

| CDGPT | Conditioned distil generative pre-trained transformer |

| MLTL | Multi-level transfer learning |

| HReMRG | Hybrid reinforced medical report generation method. |

| ATAG | Attributed abnormality graph |

| AMLMA | Adaptive multilevel multi-attention |

| VTI | Variational topic inference |

| CAMANet | Class activation map guided attention network |

| MFOT | Multi-feature optimization transformer |

| TrMRG | Transformer medical report generator |

| ASGMD | Auxiliary signal guidance and memory-driven |

| ICT | Information-calibrated transformer |

| CVAM | Cross-view attention module |

| MVSL | Medical visual-semantic LSTMs |

| MKCL | Medical knowledge with contrastive learning |

| AERMNet | Attention-Enhanced Relational Memory Network |

| FMVP | Flexible multi-view paradigm |

| RAMT | Relation-aware mean teacher |

| GHFE | Graph-guided hybrid feature encoding |

| CSAMDT | Conditional self-attention memory-driven transformer |

| CGFTrans | Cross-modal global feature fusion transformer |

| TSGET | Two-stage global enhanced transformer |

| VCIN | Visual-textual cross-modal interaction network |

| ACIE | Abundant clinical information embedding |

| MRANet | Multi-modality regional alignment network |

| KCAP | Knowledge-guided cross-modal alignment and progressive fusion |

| ATL-CA | Adaptive topic learning and fine-grained crossmodal alignment |

| ADCNet | Anomaly-driven cross-modal contrastive network |

| AC-BiFPN | Augmented convolutional bi-directional feature pyramid network |

| DCTMN | Dual-channel transmodal memory network |

| GRN | Graph reasoning network |

| CGFN | Cross-modal gated fusion network |

| CBAM | Convolutional block attention module |

| MMG | Multi-modal granularity feature fusion |

| RCAN | Recalibrated cross-modal alignment network |

| DPN | Dynamics priori networks |

| DGN | Dynamic graph networks |

| PrKN | Prior knowledge networks |

| AHP | Adapter-enhanced hierarchical cross-modal pre-training |

| CECL | Clustering enhanced contrastive learning |

| STREAM | Spatio-temporal and retrieval-augmented modeling |

| CAT | Cross-modal augmented transformer |

| MedVAG | Medical vision attention generation |

| RGRG | Region-guided report generation |

| UAR | Unify, align, and refine |

References

- Ramirez-Alonso, G.; Prieto-Ordaz, O.; López-Santillan, R.; Montes-Y-Gómez, M. Medical report generation through radiology images: An overview. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2022, 20, 986–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Mittal, A.; Singh, G. Methods for automatic generation of radiological reports of chest radiographs: A comprehensive survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 13409–13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, T.; Li, P.; Zhao, L. A survey on automatic generation of medical imaging reports based on deep learning. Biomed. Eng. Online 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R.; Kazerouni, A.; Heidari, M.; Khodapanah Aghdam, E.; Molaei, A.; Jia, Y.; Jose, A.; Roy, R.; Merhof, D. Advances in medical image analysis with vision transformers: A comprehensive review. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 91, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Lin, M.; Zhu, Q.; Xie, Q.; Wang, F.; Lu, Z.; Peng, Y. A scoping review on multimodal deep learning in biomedical images and texts. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 146, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, P.; Clatworthy, P.L.; Simpson, E.; Mirmehdi, M. Automated radiology report generation: A review of recent advances. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 18, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Tahir, A.M.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.J.; Ward, R.K. Automatic medical report generation: Methods and applications. APSIPA Trans. Signal Inf. Process. 2024, 13, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, J.; Rui, W.; Zhao, C.; Heacock, L.; Huang, C. Multi-modal large language models in radiology: Principles, applications, and potential. Abdom. Radiol. 2024, 50, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaura, T.; Ito, R.; Ueda, D.; Nozaki, T.; Fushimi, Y.; Matsui, Y.; Yanagawa, M.; Yamada, A.; Tsuboyama, T.; Fujima, N.; et al. The impact of large language models on radiology: A guide for radiologists on the latest innovations in AI. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerella, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Zhang, J.; Contreras, M.; Siegel, S.; Bumin, A.; Silva, B.; Sena, J.; Shickel, B.; Bihorac, A.; et al. Transformers and large language models in healthcare: A review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 154, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouis, M.Y.; Akhloufi, M.A. Deep learning for report generation on chest X-ray images. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2024, 111, 102320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallifant, J.; Afshar, M.; Ameen, S.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Chen, S.; Cacciamani, G.; Demner-Fushman, D.; Dligach, D.; Daneshjou, R.; Fernandes, C.; et al. The TRIPOD-LLM reporting guideline for studies using large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Jiang, H.; Han, W.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, W. A contrastive triplet network for automatic chest X-ray reporting. Neurocomputing 2022, 502, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, A.; Dowling, J.; Koopman, B. Improving chest X-ray report generation by leveraging warm starting. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 144, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Ran, R.; Hu, W.; Zhang, W.; Qin, Q.; Cui, S. S3-Net: A self-supervised dual-stream network for radiology report generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 1448–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, L.J.; Yang, X.B.; Peng, W.; Huang, Q.S. Chest radiology report generation based on cross-modal multi-scale feature fusion. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2024, 17, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouslimi, R.; Trabelsi, H.; Karaa, W.B.A.; Hedhli, H. AI-driven radiology report generation for traumatic brain injuries. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025, 38, 2630–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Fan, J.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Q.; Han, W. Attribute prototype-guided iterative scene graph for explainable radiology report generation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 4470–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xin, J.; Shen, Q.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z. End-to-end clustering enhanced contrastive learning for radiology reports generation. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025, 9, 1780–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xin, J.; Dai, B.; Shen, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z. Label correlated contrastive learning for medical report generation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 258, 108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Cui, S.; Li, T.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J. MATNet: Exploiting multi-modal features for radiology report generation. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Pei, M.; Zhao, M.; Shan, C.; Tian, Z. Prior guided transformer for accurate radiology reports generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 26, 5631–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Sang, S.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Y. Recalibrated cross-modal alignment network for radiology report generation with weakly supervised contrastive learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 269, 126394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.; Han, W. Semi-supervised medical report generation via graph-guided hybrid feature consistency. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, P.D.A.; Mathew, M.J.; Santos Neto, P.D.A.D.; Silva, R.R.V.E. The automated generation of medical reports from polydactyly X-ray images using CNNs and transformers. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bhalerao, A.; Yin, T.; See, S.; He, Y. CAMANet: Class activation map guided attention network for radiology report generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, Y.; He, K.; Zhao, Y. From observation to concept: A flexible multi-view paradigm for medical report generation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 5987–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Lu, W.; Yang, Y.; Han, W.; Huang, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhang, K. Adapter-enhanced hierarchical cross-modal pre-training for lightweight medical report generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 5303–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Sollee, J.; Collins, S.; Bai, H.; Zhang, P.; Healey, T.; Atalay, M.; Gao, X.; Jiao, Z. Multi-modality regional alignment network for COVID X-ray survival prediction and report generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 29, 3293–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Qiao, P.; Wang, L.; Ning, M.; Yuan, L.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, J. An organ-aware diagnosis framework for radiology report generation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 4253–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.; He, H.; Feng, J. Context-enhanced framework for medical image report generation using multimodal contexts. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Dhiman, C.; Kumar, D. FDT–Dr2T: A unified dense radiology report generation transformer framework for X-ray images. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2024, 35, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Guo, Y.; Yong, J.H.; Xu, F. Multi-grained radiology report generation with sentence-level image-language contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 43, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, B.; Hu, J.; Qin, Q.; Xie, K. Visual-textual cross-modal interaction network for radiology report generation. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2024, 31, 984–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y. Visual prior-based cross-modal alignment network for radiology report generation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 166, 107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, I.; Madni, T.M.; Janjua, U.I.; Batool, G.; Naz, B.; Ali, M.Q. CSAMDT: Conditional self-attention memory-driven transformers for radiology report generation from chest X-ray. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 2825–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varol Arısoy, M.; Arısoy, A.; Uysal, I. A vision-attention-driven language framework for medical report generation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Xing, S.; Li, K.; Guo, Z.; Li, G.; Yu, C. Automated generation of chest X-ray imaging diagnostic reports by multimodal and multi-granularity features fusion. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 105, 107562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, E.; Weng, Z.; Chai, J.; Li, J. TRINet: Team role interaction network for automatic radiology report generation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 183, 109275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrow, E.; Schonfeld, E. Understanding transfer learning for chest radiograph clinical report generation with modified transformer architectures. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsan, M.M.; Akram, M.U.; Rasool, G.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Baqai, M.A.A.; Abbas, M. Vision transformer and language model-based radiology report generation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras Magalhaes, G.; De S. Santos, R.L.; Vogado, L.H.S.; Cardoso De Paiva, A.; De Alcantara Dos Santos Neto, P. XRaySwinGen: Automatic medical reporting for X-ray exams with multimodal model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, L. Automated radiographic report generation purely on transformer: A multicriteria supervised approach. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 41, 2803–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, F.A.; Da Costa, C.A.; De Oliveira Ramos, G.; Maier, A.; Da Rosa Righi, R. CheXReport: A transformer-based architecture to generate chest X-ray reports suggestions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, G.; Portinale, L.; Santomauro, A. Enhancing radiology report generation through pre-trained language models. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, H.; Mukhtar, A.; Khawaja, S.G.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Khan, A.M.; Qayyum, A.; Adil, R.; Khan, Z.; Akbar, M.U.; Eklund, A. Knowledge distillation and transformer-based framework for automatic spine CT report generation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 42949–42964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yao, W.; Sun, L.; Shi, L.; Kuang, Z.; Wu, C.; Han, Q. Automated chest X-ray diagnosis report generation with cross-attention mechanism. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarghaly, O.; Khaled, R.; Elkorany, A.; Helal, M.; Fahmy, A. Automated radiology report generation using conditioned transformers. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 24, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Singh, S. ChestX-Transcribe: A multimodal transformer for automated radiology report generation from chest X-rays. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1535168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raminedi, S.; Shridevi, S.; Won, D. Multi-modal transformer architecture for medical image analysis and automated report generation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, Y.; Liu, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hua, R. TSGET: Two-stage global enhanced transformer for automatic radiology report generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tang, Q.; Zheng, B.; Lv, J.; Li, W.; Zeng, X. CGFTrans: Cross-modal global feature fusion transformer for medical report generation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 5600–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hua, R. Generating radiology reports via multi-feature optimization transformer. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 2768–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shen, X.; Wan, S.; Goudos, S.K.; Wu, J.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, W. A novel deep learning model for medical report generation by inter-intra information calibration. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 5110–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; Zhang, Y. MKCL: Medical knowledge with contrastive learning model for radiology report generation. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 146, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, W.; Li, F. Radiology report generation with medical knowledge and multilevel image-report alignment: A new method and its verification. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 146, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Yao, R.; Liang, R.; Chen, P.; Liu, T.; Dang, Y. Multi-level objective alignment transformer for fine-grained oral panoramic X-ray report generation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 7462–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zheng, S.; Huang, R.; Gao, R. Multi-task learning for lung disease classification and report generation via prior graph structure and contrastive learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 110888–110898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; You, X.; Zhang, K.; Fu, Z.; Wang, X.; Ding, J.; Sun, J.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Han, W.; et al. Spatio-temporal and retrieval-augmented modelling for chest X-ray report generation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2025, 44, 2892–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Lian, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. A chest imaging diagnosis report generation method based on dual-channel transmodal memory network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 100, 107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhu, H.; Huang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Ding, W.; Li, H.; Ran, M. Vision-knowledge fusion model for multi-domain medical report generation. Inf. Fusion 2023, 97, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Tan, L. ADCNet: Anomaly-driven cross-modal contrastive network for medical report generation. Electronics 2025, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Cheung, W.K.; Chiu, K.; Tong, T.M.; Cheung, K.C.; See, S. Attributed abnormality graph embedding for clinically accurate X-ray report generation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 2211–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, R.; Pan, R.; Yang, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hu, W.; Qing, Q. MeFD-Net: Multi-expert fusion diagnostic network for generating radiology image reports. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 11484–11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lei, H.; Huang, H.; Han, X.; Cai, Y. DPN: Dynamics priori networks for radiology report generation. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, F.S.; Kaur, N. Radiological report generation from chest X-ray images using pre-trained word embeddings. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 133, 2525–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Su, Z.; Meizhou, J.; Feng, Y.; Hu, Q.; Luo, J.; Hu, K.; Yang, Z. Optimizing medical image report generation through a discrete diffusion framework. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Mittal, A. RadioBERT: A deep learning-based system for medical report generation from chest X-ray images using contextual embeddings. J. Biomed. Inform. 2022, 135, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Yang, L.; Gao, D.; Cai, X.; Han, J.; Liu, T. Adaptive medical topic learning for enhanced fine-grained cross-modal alignment in medical report generation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 5050–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Tao, F.; Tang, M. Cross-modal augmented transformer for automated medical report generation. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2025, 13, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najdenkoska, I.; Zhen, X.; Worring, M.; Shao, L. Uncertainty-aware report generation for chest X-rays by variational topic inference. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 82, 102603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, M.; Li, X.; Shen, X.; Wan, Y.; Zhu, J. Generating medical report via joint probability graph reasoning. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Cao, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, C.; Tang, J.; Li, C. Knowledge-guided cross-modal alignment and progressive fusion for chest X-ray report generation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, R.; Zhang, H.; Hua, R. LHR-RFL: Linear hybrid-reward-based reinforced focal learning for automatic radiology report generation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2025, 44, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Peng, W. Denoising multi-level cross-attention and contrastive learning for chest radiology report generation. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025, 38, 2646–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Jia, D.; Chen, Y.; Hou, P.; Li, H. Research on chest radiography recognition model based on deep learning. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 11768–11781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirshar, M.; Paracha, M.F.K.; Akram, M.U.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Zaidi, S.Z.Y.; Fatima, T. Attention-based automated radiology report generation using CNN and LSTM. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, D.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chang, F.; Hu, S. Automatic report generation for chest X-ray images via adversarial reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 21236–21250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Mittal, A. CADxReport: Chest X-ray report generation using co-attention mechanism and reinforcement learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucan, M.; Kaya, B.; Kaya, M. Generating medical reports with a novel deep learning architecture. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2025, 35, e70062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Han, W.; Jiang, H.; Huang, Q. Joint embedding of deep visual and semantic features for medical image report generation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, G.O.; Nandedkar, A.V.; Faye, I. Translating medical image to radiological report: Adaptive multilevel multi-attention approach. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 221, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Mittal, A. CheXPrune: Sparse chest X-ray report generation model using multi-attention and one-shot global pruning. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 7485–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.; Ananthanarayana, V.S.; Mahale, A. Cross-modal deep learning-based clinical recommendation system for radiology report generation from chest X-rays. Int. J. Eng. 2023, 36, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wen, L.; Xu, Y.; Ji, C. Generating diagnostic report for medical image by high-middle-level visual information incorporation on double deep learning models. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 197, 105700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, W.; Wang, R.; Chen, J.; Qi, C.; Lukasiewicz, T. Hybrid reinforced medical report generation with M-linear attention and repetition penalty. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 2206–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z. Automatic medical report generation based on cross-view attention and visual-semantic long short-term memories. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, M.; Cheng, Q.; Shen, X.; Wan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, M. Hierarchical medical image report adversarial generation with hybrid discriminator. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 151, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paalvast, O.; Nauta, M.; Koelle, M.; Geerdink, J.; Vijlbrief, O.; Hegeman, J.H.; Seifert, C. Radiology report generation for proximal femur fractures using deep classification and language generation models. Artif. Intell. Med. 2022, 128, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveymi, S.; Dezfoulian, M.H.; Mansoorizadeh, M. Automatic generation of structured radiology reports for volumetric computed tomography images using question-specific deep feature extraction and learning. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2021, 11, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Mei, Z.; Li, X.; Tang, T.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y. A label information fused medical image report generation framework. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 150, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ren, A.; Liang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y. Improving medical X-ray report generation by using knowledge graph. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Wan, X.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; et al. Medical-VLBERT: Medical visual language BERT for COVID-19 CT report generation with alternate learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 3786–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Lee, H.; Shin, W.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, E. Multi-Modal understanding and generation for medical images and text via Vision-Language Pre-Training. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 26, 6070–6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswiga, R.V.; Shanthi, A.P. A multilevel transfer learning technique and LSTM framework for generating medical captions for limited CT and DBT images. J. Digit. Imaging 2022, 35, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Tan, Y.; Tan, L.; Qin, J.; Xiang, X. Generating radiology reports via auxiliary signal guidance and a memory-driven network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Liao, T.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z. AERMNet: Attention-enhanced relational memory network for medical image report generation. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 244, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y. An efficient but effective writer: Diffusion-based semi-autoregressive transformer for automated radiology report generation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 88, 10565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, F.F.; Mohsan, M.M.; Alshamrani, K.; Zeb, J.; Alhamami, S.; Alqarni, D. CNX-B2: A novel CNN-Transformer approach for chest X-Ray medical report generation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26626–26635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wu, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, B.; Branson, K.; Schwab, P.; Clifton, L.; Zhang, P.; Luo, J.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Aligning, autoencoding, and prompting large language models for novel disease reporting. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 3332–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demner-Fushman, D.; Kohli, M.D.; Rosenman, M.B.; Shooshan, S.E.; Rodriguez, L.; Antani, S.; Thoma, G.R.; McDonald, C.J. Preparing a collection of radiology examinations for distribution and retrieval. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 23, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; Deng, C.-Y.; Mark, R.G.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR, a de-identified publicly available database of chest radiographs with free-text reports. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvasti, N.; Roldan, M.; Uskudarli, S.; Aldana Montes, J.; Acar, B. Overview of the ImageCLEF 2015 liver CT annotation task. In Proceedings of the ImageCLEF 2015 Evaluation Labs and Workshop, Toulouse, France, 8–11 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ImageNet: A Large-Scale Hierarchical Image Database for Visual Object Recognition Research. Available online: http://www.image-net.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Li, M.; Liu, R.; Wang, F.; Chang, X.; Liang, X. Auxiliary signal-guided knowledge encoder-decoder for medical report generation. World Wide Web 2023, 26, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Lu, L.; Lu, Z.; Bagheri, M.; Summers, R.M. ChestX-Ray8: Hospital-scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3462–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Agu, N.; Lourentzou, I.; Sharma, A.; Paguio, J.A.; Yao, J.S.; Dee, E.C.; Mitchell, W.; Kashyap, S.; Giovannini, A.; et al. Chest imagenome dataset for clinical reasoning. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Online, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Radiological Society of North America. RSNA Intracranial Hemorrhage Detection [Dataset]. Kaggle 2019. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/c/rsna-intracranial-hemorrhage-detection (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Sekuboyina, A.; Husseini, M.E.; Bayat, A.; Löffler, M.; Liebl, H.; Li, H.; Tetteh, G. VerSe: A Vertebrae labelling and segmentation benchmark for multi-detector CT images. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 73, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, P.; McGough, M.; Xing, F.; Wang, C.; Bui, M.; Xie, Y.; Sapkota, M.; Cui, L.; Dhillon, J.; et al. Pathologist-level interpretable whole-slide cancer diagnosis with deep learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.; Terhljan, N.; Chung, A.G.; Zhao, A.; Surana, S.; Aboutalebi, H.; Gunraj, H.; Sabri, A.; Alaref, A.; Wong, A. COVID-net CXR-2: An enhanced deep convolutional neural network design for detection of COVID-19 cases from chest X-ray images. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 861680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Iglesia-Vayá, M.; Saborit, J.M.; Montell, J.A.; Pertusa, A.; Bustos, A.; Cazorla, M.; Galant, J.; Barber, X.; Orozco-Beltrán, D.; García-García, F.; et al. BIMCV COVID-19+: A large annotated dataset of RX and CT images from COVID-19 patients. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.01174. [Google Scholar]

- Pelka, O.; Koitka, S.; Rückert, J.; Nensa, F.; Friedrich, C. Radiology Objects in COntext (ROCO): A multimodal image dataset. In Proceedings of the 7th Joint International Workshop, CVII-STENT 2018 and Third International Workshop, LABELS 2018, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2018, Granada, Spain, 16 September 2018; Proceedings. pp. 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Song, Y.; Chang, T.H.; Wan, X. Generating radiology reports via memory-driven transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2010.16056. Available online: https://github.com/zhjohnchan/R2Gen (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Jing, B.; Xie, P.; Xing, E.P. On the automatic generation of medical imaging reports. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wu, X.; Ge, S.; Fan, W.; Zou, Y. Exploring and distilling posterior and prior knowledge for radiology report generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wu, X.; Ge, S.; Zhou, S.K.; Xiao, L. Knowledge matters: Chest radiology report generation with general and specific knowledge. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 80, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanida, T.; Müller, P.; Kaissis, G.; Rueckert, D. Interactive and explainable region-guided radiology report generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; Available online: https://github.com/ttanida/rgrg (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Hou, W.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, W.; Liu, J. Recap: Towards precise radiology report generation via dynamic disease progression reasoning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.13864. Available online: https://github.com/wjhou/Recap (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Li, Y.; Yang, B.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Li, H.; Zou, Y. Unify, align, and refine: Multi-level semantic alignment for radiology report generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 2851–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooralahzadeh, F.; Perez-Gonzalez, N.; Frauenfelder, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Krauthammer, M. Progressive transformer-based generation of radiology reports. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.09777. Available online: https://github.com/uzh-dqbm-cmi/ARGON (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–12 July 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y. ROUGE: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Text Summarization Branches Out, Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; pp. 74–81. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/W04-1013/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Zhang, T.; Kishore, V.; Wu, F.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Artzi, Y. BERTScore: Evaluating text generation with BERT. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020; Available online: https://github.com/Tiiiger/bert_score (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Vedantam, R.; Zitnick, C.L.; Parikh, D. CIDEr: Consensus-based image description evaluation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 4566–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Endo, M.; Krishnan, R.; Pan, I.; Tsai, A.; Pontes-Reis, E.; Fonseca, E.K.U.N.; Lee, H.M.H.; Abad, Z.S.H.; Ng, A.Y.; et al. Evaluating progress in automatic chest X-ray radiology report generation. Patterns 2023, 4, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.; Monshi, A.; Poon, J.; Chung, V. Deep learning in generating radiology reports: A survey. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 106, 101878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Liu, H.; Spasic, I. Deep learning approaches to automatic radiology report generation: A systematic review. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 39, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Field | Search Expression | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | [tiab] | (“Convolutional Neural Network *” OR CNN OR “Recurrent Neural Network *” OR RNN OR LSTM OR GRU OR Transformer OR Transformers OR “Attention Mechanism” OR “Encoder Decoder” OR “Sequence to Sequence” OR “Graph Neural Network *” OR GNN OR GCN OR GAT OR “Deep Learning” OR “Neural Network” OR “Neural Networks”) AND (Radiology OR Radiolog * OR “Medical Imag *” OR “Diagnostic Imag *” OR X-ray OR CT OR MRI OR PET) AND (“Report Generation” OR “Text Generation” OR “Narrative Generation” OR “Automatic Report *” OR “Clinical Report *” OR “Medical Report *”) | 158 |

| Scopus | - | Same expression as PubMed, without specific field restriction | 259 |

| Web of Science | TS= | Same Boolean expression adapted to the TS= field for topic-based search | 217 |

| IEEE Xplore | - | Same Boolean expression adjusted to the syntax requirements of the respective database | 79 |

| ACM DL | - | Same Boolean expression adjusted to the syntax requirements of the respective database | 301 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meléndez Rojas, P.; Jamett Rojas, J.; Villalobos Dellafiori, M.F.; Moya, P.R.; Veloz Baeza, A. The Current Landscape of Automatic Radiology Report Generation with Deep Learning: A Scoping Review. AI 2026, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010008

Meléndez Rojas P, Jamett Rojas J, Villalobos Dellafiori MF, Moya PR, Veloz Baeza A. The Current Landscape of Automatic Radiology Report Generation with Deep Learning: A Scoping Review. AI. 2026; 7(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeléndez Rojas, Patricio, Jaime Jamett Rojas, María Fernanda Villalobos Dellafiori, Pablo R. Moya, and Alejandro Veloz Baeza. 2026. "The Current Landscape of Automatic Radiology Report Generation with Deep Learning: A Scoping Review" AI 7, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010008

APA StyleMeléndez Rojas, P., Jamett Rojas, J., Villalobos Dellafiori, M. F., Moya, P. R., & Veloz Baeza, A. (2026). The Current Landscape of Automatic Radiology Report Generation with Deep Learning: A Scoping Review. AI, 7(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7010008