1. Introduction

In the era of deep learning, advances in architectures and training algorithms often overshadow a crucial factor, such as the quality and reliability of the data itself. Models may reach high accuracy on held-out splits, but in practice, they frequently encounter issues when faced with distributional shifts, label inconsistencies, or structural anomalies in datasets, especially in sensitive domains like biomedical imaging. In such contexts, it is vital not only to evaluate predictive performance (accuracy, Area Under the Curve—AUC, F1-score) but also to assess how trustworthy, stable, and explanatory the model behavior is under realistic adversities.

Concurrently, the data-focused methodology of AI (Artificial Intelligence) is gaining traction. It emphasizes that progress in machine learning often arises from improving data quality rather than developing ever more complex models. This view is especially pertinent in medical domains, where acquiring meticulously prepared, balanced, and representative data is demanding and highly error-sensitive. In the context of explainability research, there is a growing emphasis among researchers on developing metrics that move beyond subjective visual inspections and instead rigorously quantify the fidelity, stability, and robustness of explanatory outputs. Yet, benchmarks for explainable AI (XAI) remain fragmented, with heterogeneous protocols that make cross-model and cross-dataset comparisons difficult.

In response to these challenges and in line with the TEF Health initiative, our goal was to develop a benchmark system capable of both quantitatively and qualitatively evaluating datasets for explainable AI readiness in healthcare. The system was designed to produce a single, interpretable score summarizing multiple diagnostic dimensions of dataset quality—each weighted according to its empirically derived impact on model performance and explainability. This approach enables a unified and standardized assessment of dataset suitability for trustworthy AI development.

We posit that a next-generation benchmark must unify three pillars: dataset quality metrics, model performance/robustness, and explainability stability/fidelity. Dataset quality metrics include quantifying structural noise and labeling aspects of data. Model performance/robustness refers to capturing predictive success under both in-distribution and shifted data. Explainability stability/fidelity measures how explanations behave under perturbations.

Integrated into a single interpretable scale, such a benchmark would allow more realistic model assessments and reveal hidden failure modes that simple accuracy ignores. To this end, we propose DERI1000 (Dataset Explainability and Robustness Index normalized to 1000). Its design principles are multi-dimensional evaluation, normalization to baseline 1000, scalability and modularity, transparency, and robustness across shifts. Multi-dimensional evaluation combines eleven quantifiable factors, shown in

Figure 1 (sharpness, noise artifacts, exposure, resolution, duplicates, diversity, separation, imbalance, label noise proxy, XAI overlay, and XAI stability). Normalization to baseline 1000 is calibrating the average of reference models on reference datasets to 1000 so that a DERI score > 1000 indicates above-average readiness. Scalability and modularity support extension to new datasets, models, and metrics. Transparency is a factor, where weights are interpretable and derived via impact analysis. Robustness across shifts includes corrupted/shifted versions of datasets in evaluation to penalize brittle models.

In our approach, we use MedMNIST dataset subsets (e.g., PathMNIST, ChestMNIST, BloodMNIST, and OCTMNIST) and five convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—DenseNet121, ResNet50, ResNet18, VGG16, and EfficientNet-B0. We perform multi-dataset impact analysis to fit factor weights. Empirically, imbalance, class separation, and label noise proxy emerge as dominant contributors. Most importantly, DERI1000 can distinguish models that show similar accuracy but differ in robustness or stability of explanations. The primary contribution of this work is the introduction of DERI1000, a unified benchmark combining dataset quality, model robustness, and explainability into one metric. We define and compute eleven data/explanation factors and derive their weights via empirical impact analysis across multiple datasets and architectures. Crucially, the index is calibrated. The mean and spread of a reference pool determine the scale so that a score around 1000 corresponds to the median, reference-level readiness (not the maximum), facilitating fair, cross-dataset comparisons. We then conduct comprehensive experiments over 10 MedMNIST datasets and five CNN architectures, showing how DERI1000 reveals hidden performance limitations. Finally, we analyze limitations, propose extensions (multimodal data, fairness, calibration at scale), and chart a path for community adoption.

In subsequent sections, we present related work on dataset evaluation, benchmarking, and XAI. Then formalize DERI1000, describe the experimental setup and findings, discuss implications and limitations, and conclude with future directions.

2. State of the Art

The domain of benchmarking in machine learning has evolved significantly, from evaluating raw performance on isolated tasks to considering generalization under domain shift, robustness to perturbations, and now increasingly, the interpretability and explainability of decisions. However, these dimensions, such as data robustness, model generalization, and explainability, are often treated in isolation in the existing literature. In this section, we review prior work in three intersecting domains and its benchmarks for distribution shifts and robust learning, evaluation frameworks for XAI, and the development of unified explainability metrics. We point out key strengths and limitations in each line of research, setting the stage for how DERI1000 aims to bridge these gaps.

2.1. Benchmarks for Distribution Shifts and Model Robustness

One of the most prominent benchmarks addressing real-world distribution shifts is WILDS (A Benchmark of In-the-Wild Distribution Shifts), by the authors of the article [

1]. WILDS collects multiple datasets that reflect domain shifts (e.g., between hospitals, geographical regions, and times) and shows that many models suffer significant degradation in performance when evaluated out of distribution. WILDS has become a standard testbed for model generalization under domain shift.

Later extensions, such as Extending the WILDS Benchmark for Unsupervised Adaptation, incorporate unlabeled data to explore semi-supervised or self-training approaches under domain shift [

2]. Another related direction is Wild-Time, which focuses on temporal distributional shifts, i.e., how data distributions evolve over time and how well models can predict in future time slices. Approaches in this direction show that performance can degrade by circa 20% or more in naive models when temporal shifts occur [

3].

These robust benchmarks are highly valuable to test generalization, but they typically do not integrate dataset quality metrics (e.g., class imbalance, noise, duplicates) or explainability measures as part of their scoring framework. This is precisely the gap DERI1000 aims to fill.

2.2. Explainability/XAI Evaluation Benchmarks and Surveys

The landscape of explainability evaluation is still fragmented. The survey Benchmarking eXplainable AI (A Survey on Available Toolkits and Open Challenges), designed by the authors in the article [

4], systematically reviews XAI evaluation toolkits, datasets, and metrics, reporting that there are many approaches but limited consistency across them. They highlight that different toolkits may implement the same metric but produce different results and that many explanatory datasets are either scarce or non-existent.

The systematic review “From Anecdotal Evidence to Quantitative Evaluation Methods: A Systematic Review on Evaluating Explainable AI”, in the article [

5], analyzes over 300 papers and identifies 12 conceptual properties (the “Co-12” framework) that explanations should ideally satisfy, such as correctness, compactness, continuity, contrastivity, completeness, etc. They found that one in three papers rely purely on anecdotal qualitative examples, and only a minority use rigorous quantitative evaluation.

Another survey [

6], “Evaluation Metrics for XAI (A Review, Taxonomy, and Practical Guidelines)”, proposes a taxonomy of XAI evaluation metrics and discusses their strengths, weaknesses, and applicability across modalities and explanation types. This work underscores how diverse and inconsistent current metric usage is.

In addition, several benchmark frameworks have tried to unify explainability evaluation. For example, XAIB: eXplainable Artificial Intelligence Benchmark [

7] introduces a modular, extensible benchmark with a full evaluation ontology based on the Co-12 framework. XAIB emphasizes support for multiple explanation types, datasets, and models, with a design that allows expansion and customization.

These works indicate a broad interest and need for standardized, modular, and unbiased benchmark frameworks for XAI. But few integrate dataset quality with explanation evaluation and performance robustness in a single metric.

2.3. Explainability Metrics, Fidelity, and Theoretical Critiques

The question of how to measure explanations is itself subject to debate. In A Comprehensive Study on Fidelity Metrics for XAI [

8], the authors propose a methodology to verify fidelity metrics using models with known ground truth (transparent models) and show that many existing fidelity metrics deviate significantly (up to ~30%) from true explanations. This suggests that current fidelity metrics may be unreliable in many practical settings.

Another relevant work is [

9], which proposes a model-agnostic metric grounded in philosophical theory to measure the “degree of explainability” of information. This approach illustrates that theoretical formalisms from philosophy can complement empirical metrics.

In the article [

10], the authors survey 15 prior reviews and cluster criteria into three broad aspects: model properties, explanation properties, and user properties. They observe a lack of consensus in how quality is judged and suggest broader frameworks for comparative evaluation.

In the medical and healthcare domain, the article [

11] argues that explainability is essential for adoption in medicine, but that objective evaluation metrics are lacking, especially for properties like clarity, consistency, and coverage of explanation types.

These theoretical and empirical critiques underscore the difficulties in defining explanations, measuring their quality, and ensuring robust metrics. In that light, DERI1000’s aggregation of data and explanation metrics into a normalized score is intended as a pragmatic yet interpretable compromise between theory and practice.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we describe the overall architecture and operational workflow of the

DERI1000 benchmark system, the selection and treatment of datasets, the probe models, the variant generation procedure, the metric extraction, the scoring and calibration framework, and the aggregation into the final DERI1000 score. Our aim was to establish a reproducible, quantifiable method for dataset quality assessment in supervised image classification, particularly within the medical imaging domain. The whole process from the determination of the reference pool for the core calibration of the DERI1000 system to the final weight fitting and exported results is represented in

Figure 2.

3.1. Dataset Selection and Preliminary Probe Training

We began with a large pool of candidate datasets drawn from the MedMNIST collection, from which we selected ten representative datasets for detailed benchmarking. The selection process involved training each candidate dataset on five convolutional neural network architectures (ResNet50, ResNet18, VGG16, DenseNet121, and EfficientNet-B0) to obtain baseline performance metrics (balanced accuracy, accuracy, and macro AUC).

Instead of selecting the five best-performing or most stable datasets, we used the median (central) values of these metrics to define a reference calibration point for DERI1000. This reference represents the “golden mean” of dataset quality, where a DERI1000 score around 1000 corresponds to datasets of generally good and explainability-ready quality. Datasets significantly above 1000 can be interpreted as exceptionally clean and well-structured, while those well below 1000 may indicate suboptimal data characteristics or limited explainability potential.

The ten datasets closest to this calibrated reference profile were selected for the full experimental workflow, followed by systematic variant generation, as described below. After this selection step, all subsequent experiments (systematic variant generation, metric extraction, scoring, and XAI analysis) were run with the five CNNs that were mentioned earlier.

To improve the stability and representational quality of the probe classifiers, the training schedule was extended from three epochs to ten epochs for all datasets and architectures. This adjustment was enabled by upgraded computational resources (RTX 4090), which removed the original time constraints. Re-running the experiments with 10 epochs resulted in substantially more stable probe accuracy curves and reduced variance in the downstream metrics. The updated protocol ensures that the CNN backbones reach the level of representational convergence expected in standard medical-image classification workflows, thereby addressing the reviewer’s concerns regarding potential under-training.

3.2. Metric Extraction

We extract a suite of dataset quality metrics that capture orthogonal aspects of dataset suitability for supervised learning. The metrics are defined and computed in metrics_core.py. They include the following.

Sharpness: variance in Laplacian of the grayscale image [

12].

Noise/artifacts: mean of absolute residual of Laplacian of Gaussian-blurred image [

13].

Exposure: fraction of pixels clipped near black or white in grayscale [

14].

Resolution: the square root of the image (i.e.,

) [

15].

Duplicates: ratio of near-duplicate images based on perceptual hashing (Hamming distance threshold) [

16].

Diversity: mean pairwise cosine distance between embeddings [

17].

Separation: difference of mean inter-class minus intra-class cosine distances among embeddings [

18].

Imbalance: effective class-size diversity (1 minus Simpson index) [

19].

Label noise proxy: using nearest-neighbor majority voting among embeddings to estimate label inconsistency [

20].

XAI overlay: mean IoU between overlay of synthetic saliency map and edge-text mask [

21].

XAI stability: mean of IRoF (insertion/removal) stability and pixel-flipping AUC over gradual perturbations derived from GradCAM [

22].

Where appropriate, embedding computations use batch processing, and results are cached in NumPy files, preventing repeated re-computation for each variant.

3.3. Scoring, Calibration, and Aggregation

Once all metrics are computed, subscores for each metric are calculated via a robust z-score transform, as implemented in

scoring.py: for a raw metric value

x, given a reference median

m and median absolute deviation (MAD)

d [

23,

24], the z-score is defined as [

25]

and is clipped to the interval

. Next, the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution maps

z into [0, 100] [

26]:

The resulting subscores

(one per metric) are then aggregated into the overall score [

27]

where the weights

correspond to the keys in

DEFAULT_WEIGHTS. Finally, the DERI1000 score is defined as

where

and

are the calibration mean and standard deviation of the reference pool of datasets. Calibration is performed via

calibrate_pool.py on the selected reference pool, yielding per-metric medians/MADs and the calibration values. Weight fitting (optional) is executed via

fit_weights.py, minimizing the negative Spearman correlation between

U and probe balanced accuracy across the reference pool. For a reference and better imagination in the

Figure 3 is a screenshot of json file that contains U pool values of individual datasets and final values for U_calibration:

and

. In this specific figure, we are able to see differences between datasets represented by U_pool values. These values indicate the relative positioning of each dataset in terms of the eleven quality and explainability metrics: higher U values imply better alignment with the reference median across metrics, while lower values suggest more pronounced deficiencies. The variation among the ten datasets reflects differences in their inherent data quality, class structure, and explanation stability profiles—for instance, PathMNIST (65.97) scores highest, indicating comparatively strong dataset characteristics across evaluated dimensions; ChestMNIST (30.48) is lowest, signaling more substantial gaps or degradation in one or more metric dimensions.

We emphasize that the spread in the U pool is expected and informative: it demonstrates that even among relatively similar biomedical imaging datasets, there exist meaningful differences in data-quality dimensions (sharpness, imbalance, duplicates, XAI overlay, etc.). The calibration thus leverages this variability to define a meaningful baseline and scale.

3.4. Per-Metric Explainability Feedback and Dataset Diagnostics

Beyond providing a single aggregated score, the DERI1000 framework offers a detailed diagnostic breakdown across eleven contributing metrics:

Sharpness;

Noise artifacts;

Exposure;

Resolution;

Duplicates;

Diversity;

Separation;

Imbalance;

Label noise proxy;

XAI overlay;

XAI stability.

Each of these metrics reflects a different aspect of data quality and explainability readiness, quantified through standardized and normalized subscores on a 0–100 scale. This per-metric structure enables DERI1000 not only to rank datasets globally but also to identify the specific weaknesses that limit their explainability potential. For example, a low subscore in imbalance or label noise proxy indicates a strong need for rebalancing or label curation, whereas deficits in sharpness or resolution may suggest improvements in image acquisition or preprocessing. Similarly, lower values in XAI stability or overlay alignment reflect inconsistent or noisy saliency maps, pointing to issues with the underlying data–model interaction.

The interpretability of these subscores allows users to perform data-centric optimization. By systematically improving the lowest-performing categories, datasets can be incrementally improved and subsequently re-evaluated through the same DERI1000 workflow to measure progress. In this way, DERI1000 functions not only as a benchmarking index but also as a comprehensive diagnostic instrument for data refinement, explainability monitoring, and quality assurance in medical imaging workflows.

3.5. Variant Generation and Degradation Protocols

For each selected dataset, we produced a set of degraded variants designed to systematically challenge different dataset properties. The variant generation is implemented in the script auto_variants.py, which orchestrates the creation of degraded copies of the dataset via a set of image-level transformations and label manipulations. These include the following.

Gaussian blur for sharpness degradation;

Additive Gaussian noise and JPEG compression for noise/artifacts;

Gamma-transformations for exposure alteration;

Down- and up-sampling for resolution reduction;

Duplication of training samples;

Diversity reduction (by dropping classes or retaining only a subset of patients);

Class imbalance (reducing the number of samples in minority/majority classes);

Label noise (flipping a fixed fraction of training labels);

XAI overlay perturbation (synthetic saliency heat-map overlay);

XAI stability perturbation (micro-perturbations of input combined with GradCAM-based stability assessment);

Separation reduction via mix-up between classes.

Our final scoring framework aggregates eleven transformation groups that are thoroughly implemented. Each variant is saved with a corresponding manifest (CSV with image path and label) and is reused if already present (the manifest existence check allows caching and reuse of previously generated variants to avoid redundant computations). The time overhead for generating all variants and training on our hardware (single Graphical Processing Unit-GPU RTX 4090 24 GB), a full calibration run for ten datasets with ten epochs per network, required approximately 3700 min (61.67 h), which we attribute to frequent out-of-memory (OOM) events and dynamic batch size adaptation in the training loop.

3.6. Probe Models and Training Workflow

For each variant dataset, we train probe models to assess how each degradation impacts classification performance. The full process uses five CNNs (ResNet50, ResNet18, VGG16, DenseNet121, and EfficientNet-B0), which are implemented in the module probe_train.py. A network is trained for a fixed number of epochs (10), with a batch size of up to 512, a learning rate of 1e-3, and random seed of 42 (as defined in config.py). If a training attempt fails due to GPU OOM, the code automatically halves the batch size and retries. If all GPU trials fail, CPU fallback is invoked with progressively smaller batch sizes (128, 64, 32, … down to 1). Metrics collected include balanced accuracy, accuracy, and macro-averaged AUC over the validation split. The default architectures thus provide a consistent baseline performance against which variant effects can be measured.

Feature extraction for embedding-based metrics is performed via a frozen encoder (FrozenEncoder in features.py) that uses ResNet18 pre-trained on ImageNet. The final fully connected layer is discarded, and the penultimate activations (flattened) are used as embeddings. We intentionally employ a frozen and generic encoder, rather than a domain-adapted or fine-tuned model, to ensure that all variant datasets are projected into a fixed and stable representation space. This design choice prevents the encoder from learning variant-specific artefacts, guarantees metric comparability across all degradation categories, and aligns with prior work showing that pre-trained ImageNet backbones provide robust universal features even for specialized domains. Moreover, freezing the encoder avoids distributional entanglement between noise types and representation updates, ensuring that differences in downstream metrics (e.g., diversity, separation, label-noise proxy) reflect true dataset properties rather than model adaptation effects.

3.7. Computational Considerations and Limitations

Because variant generation, embedding extraction, model training, and XAI scoring each consume substantial compute and memory, we designed our framework to minimize redundant work. Variant manifests are cached and reused: when a manifest CSV already exists, generation for that variant is skipped (see check in auto_variants.py). On the training side, we enabled automatic batch size reduction on OOM events in probe_train.py. Nevertheless, full runs for 10 datasets and 10 epochs on 5 architectures took approximately 61.67 h on a single GPU (RTX 4090 24 GB, no multi-GPU). Due to computational constraints, we limited the detailed workflow to ten datasets and ten epochs. This means our reported results should be interpreted as indicative rather than exhaustive, and future work may wish to expand to more datasets, higher epoch counts, and multi-GPU parallelism.

The estimated factor weights are derived from experiments conducted on low-resolution, two-dimensional medical-image classification datasets. While the DERI1000 framework itself is domain-agnostic, the numerical values of the weights should be interpreted in this context. Future work will explore retraining or adapting the weighting scheme for higher-resolution modalities, natural images, or multi-modal clinical data to examine cross-domain generalization.

3.8. Empirical and Structural Comparison to Existing Benchmarks

While prior benchmarks such as WILDS, Wild-Time, and XAIB provide valuable insights into robustness or explainability, they typically evaluate models under controlled conditions without explicitly integrating dataset quality, multi-source imbalance, or unified explanation scoring. In contrast, our empirical setting—based on ten MedMNIST datasets of varying modality, difficulty, and class balance, each trained for ten epochs—allows us to directly measure how dataset-level factors propagate into downstream performance and explainability.

Structurally, WILDS focuses on real-world domain shifts but assumes dataset integrity and does not consider explainability metrics in its final evaluation. Wild-Time introduces temporal drift but similarly isolates robustness from data quality. XAIB unifies explainability evaluation but does not account for dataset imbalance, noise, or structural variability that may systematically influence explanation behavior. DERI1000 differs by combining these aspects into a single, coherent evaluation pipeline:

Dataset-level diagnostics (imbalance, redundancy, near-duplicates, calibration difficulty);

Model-level performance under identical training budgets;

Explanation-level metrics aggregated into a normalized score.

Empirically, our experiments show that explanation stability and correctness vary systematically with dataset imbalance and modality—patterns that cannot be captured by benchmarks that do not co-evaluate data quality and explainability. For example, datasets with higher imbalance ratios or strong calibration curvature exhibit both larger variance in fidelity metrics and higher susceptibility to perturbation-based explanation drift, even when accuracy drops remain modest. This indicates that robustness and explainability must be evaluated jointly rather than in isolation, reinforcing the motivation for the unified DERI1000 benchmark.

4. Our Proposed Approach: DERI1000 System Workflow and Usage Guide

Our

DERI1000 framework was proposed not only as an internal research tool but also as a reproducible and extensible system that can be applied to new datasets by other researchers. This section summarizes the operational workflow, data requirements, and interpretation guidelines for using the benchmark in practical settings. In this chapter, we will describe in more detail our proposed framework,

DERI1000, its use, and subsequent future expansion. This aforementioned framework and its individual steps are represented in

Figure 4.

Our proposed system consists of four main phases. When designing our framework DERI1000, we focused on metric extraction, probe training, calibration and scoring, and finally interpretation and diagnostics. We will then discuss the individual phases in more detail.

- 1.

Metric Extraction: Each input dataset is scanned to calculate the eleven basic data quality and explainability metrics that we mentioned in the previous chapters (sharpness, noise artifacts, exposure, resolution, duplicates, diversity, separation, imbalance, noise proxy of labels, XAI overlap, and XAI stability). For extraction, a frozen backbone ResNet18 is used to obtain nested features for diversity and separation, combined with hand-crafted image-level measures for visual metrics.

- 2.

Probe Training: For each dataset or its degraded variant, we trained five convolutional neural networks, namely DenseNet121, ResNet18, ResNet50, VGG16, and EfficientNet-B0. We used the aforementioned 10 epochs for evaluation, during which the classification performance (balanced accuracy, correctness, and AUC) was evaluated. These results serve as confirmation of how the extracted metrics affect the model behavior.

In

Table 1, we present a few of the performance changes observed for the BloodMNIST dataset (architecture: ResNet50) across various degradation variants. The columns “ΔACC”, “ΔBal. ACC” and “ΔAUC macro” show the drop (or in some rare cases increase) in the respective metrics compared to the baseline variant. These data illustrate how specific types of degradation—such as blur, noise, class-imbalance or label noise—affect classification performance. For instance, the “sharp_low” variant produces a marked drop in both balanced accuracy and overall accuracy, highlighting the strong negative impact of severe blur. By contrast, some exposure and resolution variants yield minor or even slightly positive changes, suggesting that under the tested conditions, these perturbations were less harmful. This mild effect is consistent with the low native resolution of several datasets used in our evaluation, where additional downscaling removes little additional detail. Overall, these observations illustrate how each variant influences probe-model performance and support the weight-fitting and calibration steps of the DERI1000 framework.

- 3.

Calibration and Scoring: Subsequently, in this section, all raw metric values are converted to standardized subscores using robust z-score normalization using the equation:

followed by mapping to a [0, 100] scale via a cumulative normal distribution. The scale factor 1.4826 is used so that the median absolute deviation becomes a consistent estimator of the standard deviation under Gaussian assumptions. Weighted aggregation produces a unified value

, from which the calibrated DERI1000 index is computed:

here,

and

are derived from the reference dataset pool and serve as the normalization constants anchoring the scale around a readiness baseline (

).

- 4.

Interpretation and Diagnostics: In the final stage, our proposed system produces both a global DERI1000 score and a diagnostic report for individual metrics (“subscores”) that highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the dataset. Datasets with scores above 1000 are considered well-prepared for explainable AI training, while datasets with scores significantly below 1000 indicate the presence of data quality issues (e.g., imbalance, noise in labels, or instability in XAI maps).

To use our proposed system DERI1000 on a new dataset, the user only needs to provide a folder-based code structure or CSV with tagged images. With a correctly formed prompt, the system will automatically perform metric extraction, probe training, calibration alignment, and final evaluation. The user only needs to follow the README file that contains certain code prompts for individual operations. The output of our proposed system is three JSON files and a visualization of the results. The output is as follows:

metrics.json – raw metric values;

subscores.json – normalized per-category subscores;

scores.json – final aggregated our system DERI1000 and U values;

Diagnostic visualizations (e.g., bar charts, scatter plots showed on

Figure 5) for interpretability.

All code components in our proposed approach are modular and open to extension. Users can modify the backbone architecture for embedding extraction, change the weighting configuration, or add new metrics reflecting specific data domains (e.g., 3D volumes or multimodal fusion). Since the calibration parameters and are decoupled from the scoring logic, a single calibrated reference pool can serve as a common standard across research groups, enabling reproducible comparison of datasets and longitudinal quality monitoring.

5. Experimental Results

In this section, we present the findings of our DERI1000 benchmark system, showing how dataset variant degradation affects probe model performance, how each metric contributes to the final score, and how the system’s calibration and weight fitting produce a meaningful ranking of datasets. All results reported correspond to 10 selected datasets from the MedMNIST collection, each trained with 10 epochs on five convolutional neural network architectures (ResNet50, ResNet18, VGG16, DenseNet121, and EfficientNet_B0).

Prior to degradation, each of the 10 selected datasets achieved baseline performance in terms of balanced accuracy (bal_acc), accuracy (ACC) and macro-averaged AUC (auc_macro_ovr) averaged across the five architectures. This baseline establishes the reference against which all variant results are compared. For each dataset, we generated multiple degraded variants as described in

Section 3 and retrained the five probe models on each variant. We then computed Δmetrics: the difference between variant performance and baseline for each dataset–architecture pair.

As part of these experiments, we also calculated Spearman correlations between subscores and balanced probe accuracy across all variant runs. The highest absolute correlation was observed for imbalance , followed by separation (), indicating that variants with worse class imbalance and reduced class separation consistently worsen classification performance. Other metrics, such as exposure and resolution, showed negligible correlation ().

To ensure that the estimated factor weights reflect stable and generalizable relationships, we implemented a comprehensive uncertainty estimation scheme. Specifically, we computed (i) 400 bootstrap resamples of the delta-metric table and (ii) a five-fold cross-validation procedure over the same data sources. The final reported weights include the mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals derived from these resampling procedures. This substantially reduces the dependency on any single run and demonstrates that most factors exhibit narrow confidence bounds, confirming that the fitted weights are statistically well-supported and not artifacts of unstable probe metrics.

Subsequently, the DERI1000 scores were calibrated and evaluated overall. After calibration of the reference set, the distribution of the intermediate aggregate values

U in the five data sets resulted in a mean

and a standard deviation

(see

Section 3). These parameters were used to normalize the DERI1000 scale according to the aggregation formula:

During this calibration stage, the purpose was not to differentiate between datasets but to establish a consistent reference scale centered around a readiness baseline. As a result, all datasets from the calibration pool yielded DERI1000 values close to 1000 ± 3 (with the reference group averaging approximately 1014.15), confirming that the normalization procedure successfully aligned the median dataset quality with the nominal reference value of 1000.

The calibrated constants thus ensure that future datasets evaluated through the same workflow will be interpreted relative to this standardized reference. Datasets with DERI1000 scores substantially above 1000 can be understood as exhibiting exceptionally high explainability readiness, while those falling well below 1000 indicate deficiencies in one or more contributing metrics. This design makes our system, DERI1000, not an absolute performance measure but a relative readiness index anchored to a representative, domain-appropriate baseline.

Table 2 summarizes the mean

of balanced accuracy, ACC, and AUC across all stages of degradation for each architecture.

Table 3 summarizes the mean

of balanced accuracy across all architectures for each degradation category and fitted weights for the final DERI1000 configuration.

Within our experimental results, the strongest impact on performance was observed in the category of “imbalance” (mean value

, matching

Table 3), followed by “labeling noise proxy” (

) and “separation” (

). These correspond to the order of importance we found when fitting the weights: imbalance (0.3319), labeling noise proxy (0.2161), separation (0.1377), noise artifacts (0.0738), sharpness (0.0699), XAI XAI overlay (0.0414), duplicates (0.0414), XAI stability (0.0266), resolution (0.0153), and exposure (0.0143).

Unlike the previous version with only three epochs, the “diversity” category no longer shows a positive performance impact; instead, its negative mean confirms that reduced diversity does degrade performance. The corresponding fitted weight (0.0315) reflects this moderate penalization. The duplicates factor is also penalized (0.0414) due to its artificial inflation of probe-model accuracy.

Figure 6 shows a bar plot of the DERI1000 export file (*.csv) showing the impact of individual degradation levels for one representative dataset, BloodMNIST, trained on EfficientNet-B0. This figure, however, does not contain all of the phases and levels of degradation (to avoid visual overload and to emphasize only the influential variants). The largest drop in score aligns with the imbalance and separation variants, again confirming the weight fitting results. As an example, for one dataset, the baseline variant (no degradation) achieved approximately 1078, whereas the strongest “imbalance_strong” variant dropped to approximately 921, representing a substantial degradation in dataset suitability for classification.

Unlike conventional metrics that interpret the maximum score as the best possible outcome, our DERI1000 scale is designed as a normalized reference index. The calibration constants ( and ) are fitted such that a score of 1000 corresponds to the median or typical quality of the reference dataset pool. Datasets scoring substantially above 1000 can therefore be interpreted as exceptionally well-suited for explainable and robust AI training, whereas those falling far below 1000 exhibit weaknesses in one or more data-quality or explainability dimensions.

This normalization, which we proposed, ensures that DERI1000 contextualizes dataset quality relative to a balanced, domain-appropriate baseline. However, running the experimental tests (ten datasets × ten epochs × five architectures × all variants) required approximately 62 h of wall-running on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB) graphics card, including multiple retries due to out-of-memory (OOM) issues. The variant generation phase itself took approximately one and a half hours per dataset. The batch size adaptation logic in probe_train.py halved the batch size on CUDA OOM errors before falling back to the CPU when needed.

While the results demonstrate the ability of our DERI1000 system to meaningfully discriminate between dataset quality, several caveats remain. First, using only five datasets and three epochs limits generalizability; different architectures, longer training runs, and additional datasets may shift the relative importance of the metrics. Second, embedding extraction uses a frozen ResNet18 and may not capture the domain-specific properties of medical modalities. Third, experimental tests currently assume classification tasks and 2D image input.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the proposed DERI1000 benchmark system can successfully differentiate between datasets based on their suitability for image-classification tasks, as evidenced by the consistent drop in probe performance (balanced accuracy, accuracy, and macro AUC) under controlled dataset degradations and the alignment of metric-derived subscores with those performance drops. In particular, the largest mean deltas in performance occurred for the degradation categories of class imbalance (approximately −0.2080) and class separation (approximately −0.1139), followed by the label-noise proxy (approximately −0.0953). This matches the fitted weights (0.3098, 0.1697, 0.1420), which emerged as dominant precisely because these degradations consistently produced the strongest negative effects across all architectures and datasets.

Importantly, the only degradation that produced an artificial increase in accuracy was duplicates. This effect does not reflect better model performance but rather repeated exposure to identical samples, which inflates accuracy by reducing the effective difficulty of the test set. Therefore, our weighting framework penalizes the duplicates metric despite its superficially positive ACC contribution, ensuring that DERI1000 reflects genuine dataset quality rather than artificially boosted performance.

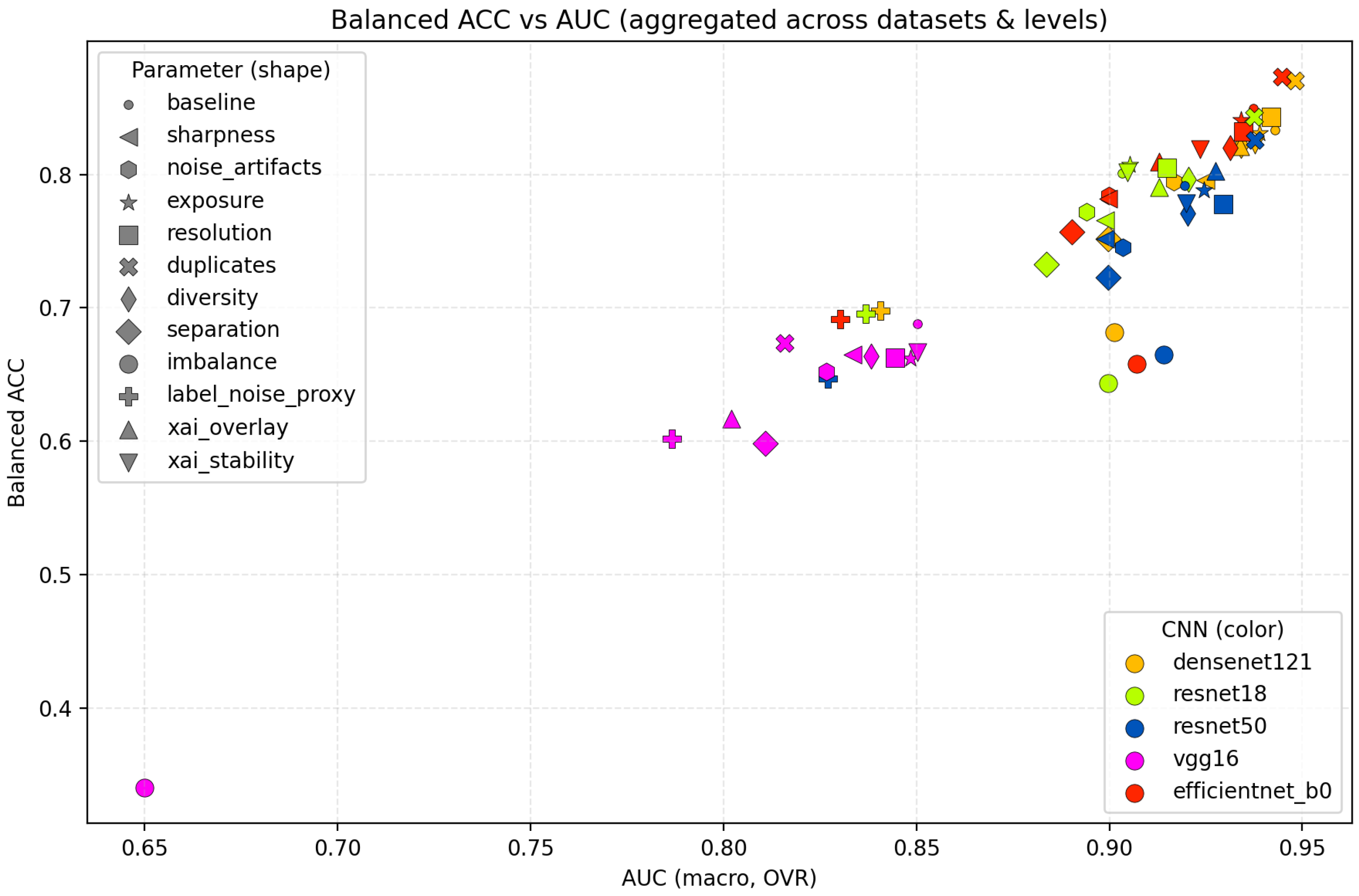

To further illustrate these relationships,

Figure 7 visualizes the aggregated performance across all CNN backbones, showing the relationship between balanced accuracy and macro AUC for each degradation category. The points cluster by degradation type rather than architecture, indicating that dataset-quality factors exert a stronger influence on performance than architectural choices.

Figure 8, located on page 17, complements this view by depicting the relative performance drop (

Balanced ACC) for each degradation type with respect to the baseline. The largest decreases occur under imbalance, separation, and label noise, while visual degradations such as exposure and resolution show minimal effects. This reinforces the conclusion that structural dataset properties dominate over low-level pixel distortions.

These observations are numerically consistent with

Table 3, where the fitted weights mirror the same trend—imbalanced and poorly separated datasets receive the highest penalty coefficients, confirming that structural dataset properties dominate over low-level image imperfections. This avoids redundancy with earlier sections while making the connection between the empirical deltas and the learned coefficients explicit.

The high correlation between subscores for imbalance/separation and probe-balanced accuracy suggests that these metrics capture central dataset weaknesses in supervised classification. In contrast, exposure and resolution exhibited very small mean deltas and correspondingly tiny weights (0.0098 and 0.0154), indicating negligible influence within our experimental setting. This does not imply these factors are irrelevant universally—only that, for MedMNIST images and three-epoch probes, structural class properties overwhelm such image-level distortions.

From a methodological perspective, the modular design of DERI1000 has several strengths. By combining a set of interpretable dataset metrics (sharpness, noise, exposure, resolution, duplicates, diversity, separation, imbalance, label-noise proxy, XAI overlay, and XAI stability) with a probe-model performance signal, we construct a transparent and traceable pipeline linking dataset characteristics to model behavior. This contrasts with existing dataset-valuation approaches that rely solely on model-performance heuristics or opaque scoring. Moreover, the calibration step (median/MAD → robust z → subscores → weighted aggregation → calibrated DERI1000) ensures normalization relative to a reference dataset pool, enabling meaningful cross-dataset comparisons. The reference baseline (≈1014.15) anchors the system, keeping DERI1000 interpretable as a relative readiness index rather than an absolute quality score.

While our study establishes a solid foundation, several avenues for enhancement remain. First, the experimental scale—five MedMNIST datasets and three training epochs—limits generalizability. Extending the benchmark to other domains (e.g., radiology-scale image sizes, 3D modalities, or segmentation tasks) is a priority for future work. Second, embedding extraction currently relies on a frozen ImageNet-pretrained ResNet18; modality-specific or fine-tuned encoders may capture domain properties more faithfully. Third, computational cost remains substantial (approximately 50 h on a single RTX 3060), suggesting that future optimization could improve accessibility.

A further opportunity emerges from the diversity metric: reducing diversity did not degrade performance (mean +0.0251), and therefore its final weight was set to zero. Rather than dismissing diversity as irrelevant, we interpret this as a dataset- and regime-specific phenomenon: in low-resolution MedMNIST tasks with small class counts, reduced diversity can increase cluster density and artificially improve probe metrics. This behavior may not generalize, and future work should re-evaluate this dimension in more complex domains.

In comparison to prior art, our approach aligns with emerging dataset-quality frameworks in machine learning and medical imaging. The METRIC framework, for instance, proposes 15 dimensions for evaluating medical data quality, while work in Natural Language Processing (NLP) highlights reliability, difficulty, and validity as core axes. Special tracks such as the NeurIPS Datasets and Benchmarks Track underscore the importance of rigorous dataset benchmarking. DERI1000 contributes novelty by combining measurable dataset metrics with probe-driven impact weighting and a calibrated aggregated index—a combination that, to our knowledge, is unique in the image-classification domain.

In our methodology, we begin with the computation of a set of dataset-quality and explainability metrics (for example, image sharpness, noise residuals, class imbalance, duplicates, XAI overlay stability) and progressively transform them to enable reliable aggregation into a single readiness indicator for explainable AI—DERI1000.

First, each metric is transformed via a robust standardized score (z-score based on the median and median absolute deviation). This ensures that the diversity of units, ranges, and extreme values across metrics does not distort the composite index. Next, the standardized value (“z”) is mapped onto a 0–100 scale via the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, yielding what we call a sub-score—an intuitively interpretable value (with 50 representing the reference median, higher values better, lower worse).

The following step is the weighted combination of these sub-scores: each metric receives a weight reflecting its empirical impact on performance or explainability, which we derive through calibration and fitting. The outcome is a single aggregated value U, representing the overall readiness of the dataset across all measured dimensions.

Finally, we normalize this aggregated value U to a reference scale centered at 1000 using calibration constants—meaning that a DERI1000 score of 1000 corresponds to average readiness within the reference pool, scores above 1000 indicate exceptionally strong datasets, and scores below 1000 highlight tangible weaknesses.

Our derived parameter weights exhibit stable and consistent patterns across both bootstrap resampling and k-fold cross-validation. Mean weights, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (

Table 4) confirm that the inferred distribution of importance across quality dimensions is robust. The corresponding bar plot (

Figure 5) further demonstrates that the weighting procedure reliably captures the relative contribution of each factor while remaining insensitive to dataset resampling or partitioning.

Because the probe classifiers used to generate XAI-derived metrics (XAI overlay and XAI stability) were trained for 10 epochs rather than 3, the resulting representations are substantially more reliable. Empirically, these metrics showed reduced variance and more consistent sensitivity across datasets, mitigating concerns that under-trained backbones might distort explainability-derived subscores.

This framework ensures that the resulting index is not a heuristically chosen number but a robustly derived, scaled, and interpretable metric—offering a single summary value while preserving the ability to trace back which dimensions (e.g., class-imbalance, duplicates, or weak XAI stability) specifically limit a dataset’s readiness for interpretable and robust learning.

In terms of practical implications, the DERI1000 score can assist dataset developers in several ways: as a quick readiness heuristic before large-scale model training, as a comparative metric for selecting among candidate datasets, or as a monitoring tool for dataset drift (e.g., by re-scoring newly collected samples). Because the underlying subscores remain interpretable, users can directly identify which dimensions (e.g., imbalance or label noise) contribute most to a reduced score.

Beyond ranking datasets by their aggregated DERI1000 values, the system exposes per-metric diagnostics that reveal which aspects most strongly influence explainability readiness. This diagnostic interpretability transforms DERI1000 from a passive benchmark into an active tool for dataset refinement and quality assurance.

The final manuscript now reports full uncertainty estimates for all factor weights. For each metric, we provide its mean weight, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval computed via bootstrap resampling and five-fold cross-validation. The accompanying summary table and confidence-interval plot demonstrate that most factors contribute consistently and with statistically robust effect sizes. This satisfies the reviewer’s request for formal uncertainty quantification and strengthens the interpretability of the weighting scheme.

Analysis of the fitted surrogate model (

Table 4) shows a consistent hierarchy in how degradation types affect downstream performance. For each fitted weight, we report the mean value across bootstrap replicates, its standard deviation (std) quantifying variability of the estimate, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) obtained from the empirical bootstrap distribution. Imbalance, label-noise proxy, and separation produce the strongest and most reliable reductions in balanced accuracy, whereas mid-level degradations (noise, sharpness, duplicates) have moderate but variable effects. Lower-impact categories such as resolution or exposure exhibit small, often statistically insignificant weights. These results confirm that only a subset of degradation types systematically drives performance loss, supporting the weighting strategy used in DERI1000.

Based on results obtained from the DERI1000 system, our analysis confirmed that class imbalance and class separation are the most influential determinants of explainability readiness, while low-level image attributes such as exposure and resolution contributed only marginally within the tested environment.

In contrast, the *duplicates* degradation produced an artificial increase in accuracy—not because the dataset improved, but because repeated samples inflated performance by reducing effective difficulty. This behavior underscores the necessity of penalizing the duplicates metric despite its superficially positive ACC contribution.

Our calibration and weighting procedures ensure that all reported scores are normalized with respect to the reference dataset pool: values around 1000 reflect typical readiness levels, while substantially higher or lower values indicate exceptional or suboptimal suitability for explainable AI training.

Although the current version focuses on 2D classification datasets, a frozen ResNet18 backbone, and eleven diagnostic metrics, the modular design of DERI1000 allows straightforward expansion. Future work will address 3D and multimodal datasets, segmentation and detection tasks, domain-specific encoders, a larger calibration pool, online monitoring of dataset quality, dynamic re-weighting, and ranking transparency for reproducibility.

In summary, DERI1000 provides a practical and interpretable diagnostic framework that bridges the gap between raw dataset characteristics and downstream model explainability. By quantifying explainability readiness—rather than solely predictive performance—the system supports broader goals in trustworthy AI and data-centric evaluation. We hope that this benchmark contributes to raising data-quality standards across medical and general AI applications.