Abstract

Capacity building efforts in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are indispensable for the achievement of both individual and collective ocean-related 2030 agenda priorities for sustainable development. Knowledge of the individual capacity building and research infrastructure requirements in SIDS is necessary for national and international efforts to be effective in supporting SIDS to address nationally-identified sustainable development priorities. Here, we present an assessment of human resources and institutional capacities in SIDS United Nations (UN) Member States to help formulate and implement durable, relevant, and effective capacity development responses to the most urgent marine issues of concern for SIDS. The assessment highlights that there is only limited, if any, up-to-date information publicly available on human resources and research capacities in SIDS. A reasonable course of action in the future should, therefore, be the collection and compilation of data on educational, institutional, and human resources, as well as research capacities and infrastructures in SIDS into a publicly available database. This database, supported by continued, long-term international, national, and regional collaborations, will lay the foundation to provide accurate and up-to-date information on research capacities and requirements in SIDS, thereby informing strategic science and policy targets towards achieving the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) within the next decade.

1. Introduction

In September 2015, all 193 United Nations (UN) Member States adopted an agenda for sustainable development, including 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as an over-arching policy framework through to the year 2030 [1]. The agenda calls for worldwide action among governments, policy makers, private sectors, research communities, and the civil society to actively cooperate to mobilize global efforts around economic, social, and environmental issues in a balanced and integrated manner [1]. SDG 14 (Life Below Water), which focuses on human interactions with the ocean, seas, and marine resources, is critical to an integrated approach to achieve the SDGs agenda [2,3,4]. SDG 14 is underpinned by seven targets and three means addressing conservation, capacity building, ocean governance, and sustainable use and management of the ocean, seas, and marine resources (Table S1) [1,4]. SDG 14 is thus closely linked with other SDGs, such as Ending Poverty (SDG 1), Ending Hunger (SDG 2), Good Health and Well-Being (SDG 3), Climate Action (SDG 13), and Creating Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8), and has therefore a cross-cutting role in the agenda [2,3,4,5].

With the growing awareness of the rapid degradation and over-use of oceans and the importance of healthy oceans and seas to the future of humanity, SDG 14 is gaining increasing attention by governments, industry, scientists, and the public [6]. This awareness led the UN General Assembly to proclaim a Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, also referred to as the ‘Decade’, which starts in 2021 and ends in 2030 [6,7]. The primary focus of the Decade is to provide a common framework to support countries in achieving their ocean-related 2030 agenda priorities for sustainable development [7]. The Decade strives to enable UN Member States to (1) work together to protect the health of our shared oceans by coordinating existing programs in ocean science, observations, monitoring, and data exchange [7] and (2) build the scientific and institutional capacity needed to generate scientific knowledge to improve science-based management of our ocean space and resources and thus increase the ability to better inform policy [7].

In the past, interdisciplinary ocean science has made great progress in exploring, describing, understanding, modelling, and enhancing current knowledge of the ocean system due to a myriad of national and international funding efforts and research projects, such as those under the umbrella of the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR; [8]). This knowledge helped to improve and create new technologies, tools, methods, collaborations, partnerships, projects, and scientific infrastructure to achieve a better understanding of the current state of our oceans, adopt appropriate mitigation and management strategies, improve the ability to predict ocean changes in the future, and inform policy and ocean governance [7,8]. However, there are major disparities in the capacity around the world to undertake marine scientific research [7,9] required to achieve national and regional SDG 14 targets. Global ocean science capacities are unevenly distributed, and Small Island Developing States (SIDS; Table S2; [10]) and the Least Developed Countries (LDC; [11]) suffer the most since they are limited in capacity and capability [7,9,12] to tackle global and national ocean-related issues such as climate change, marine pollution, ocean acidification, overfishing, seafood safety and trade, food security, sustainable aquaculture, and degradation and loss of biodiversity and marine habitats [13,14].

The SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action (SAMOA) Pathway, which is an integral part of the 2030 agenda for the SDGs, reaffirms that SIDS remain a special case for sustainable development, recognizing their ownership and leadership in overcoming their unique challenges but also underscoring the need for partnerships with, and support of, the international community to help the SIDS achieve their SDGs over the next 10 years [15]. The pathway represents the commitments made by 115 SIDS Heads of State and Government as well as high-level representatives and is an official document formally adopted by UN Member States in September 2014. The SAMOA action plan recognizes that SDG 14 in particular is one of the most critical goals for SIDS whose societies, cultures, livelihoods, and economies are inherently linked with healthy, productive, and resilient oceans [7,15].

The success of SDG 14 and the Decade is critically dependent on global capacity building efforts and resource sharing between developed and developing countries [6]. Consequently, supporting SIDS, which frequently have weaker institutional capacity and limited financial resources [13], is indispensable to both individual and collective achievement of SDGs. It is commonly recognized that SIDS have a need for more tertiary education in environmentally relevant fields, technical expertise, training, access to tools, new technology, ocean information, ocean literacy, monitoring networks, data products, and infrastructure and logistics [13]. However, knowledge about their current states of national research capacities and infrastructures and their associated individual capacity building requirements is still scarce. This scarcity of information complicates the efforts of national and international agencies, programs, projects, and collaborations to effectively support SIDS in achieving long-term, sustainable and indeed necessary research capacities and capabilities. The implementation of effective capacity development in SIDS is also hindered by structural hurdles within governmental, national, and regional institutions, i.e., the lack of centralization, as well as the shortage of ownership, leadership, and coordination; the scarcity of active stakeholder participation; the lack of coordination and fragmentation between capacity building efforts at national and international levels; and short-term, project-based approaches of capacity development aids [12,16]. These constraints, among others, prevent fast decision-making and the implementation of ocean science-related issues into national and regional policies and thus exacerbate the challenges of global capacity building efforts and resource sharing [16]. A successful implementation of capacity building in SIDS will thus rely on a holistic approach to address all the gaps in the capacity needs and challenges of SIDS [12,16]. The first key objective for a holistic capacity building process is the development of appropriate human and institutional capacity to engage in (1) the identification of problems and needs in a local context, (2) the collection of scientific information, and (3) the implementation of science-based national plans and international agreements to ensure effective mitigation and adaptation solutions [12,16].

Several regional, national, and international programs and initiatives are already in place to support SIDS to acquire the prerequisite capacity and infrastructure (SDG 14.a) required to understand, monitor, and protect their marine environment in line with nationally identified targets under SDG 14 and the SAMOA Pathway and to fulfil their obligations in the framework of Global Conventions. One such program is the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA’s) Technical Cooperation (TC) Programme established in 1957, which among other things, focuses on the safe and peaceful application of nuclear science, technologies, and knowledge to find practical solutions, in this case, for marine environmental challenges. Nuclear and isotopic techniques are essential tools to help identify, monitor, mitigate, and adapt to the effects of sustained climate- and ocean-change such as ocean warming, ocean acidification, biotoxins (e.g., harmful algal blooms), and contaminants (e.g., radionuclides, trace metals, and persistent organic pollutants) [17], and thus directly contribute to SDG 14.1 and 14.3. The TC Programme is the main mechanism through which the IAEA assists and delivers services to its Member States including the development of research capacity to transfer marine technology, in order to improve ocean health and to enhance the contribution of marine biodiversity to the development of developing countries, in particular SIDS and LDC (SDG 14.a). The program helps Member States to build, strengthen, and maintain human expertise and institutional capacities in order to (1) define national needs; (2) make informed decisions on action plans and measures to protect the oceans; (3) assure the sustainable delivery of ecosystem services; and (4) ensure sustainable socioeconomic development [17].

Currently, the IAEA provides technical support to 23 of the 38 SIDS Member States (Table S3) in areas such as the marine environment, health and nutrition, food and agriculture, energy, nuclear knowledge development and management, water and the environment, and industrial applications and radiation technology. Nevertheless, most SIDS still have a low capacity (i.e., limited infrastructure; low technical and institutional capacity; little financial, human, and material resources; and lack of expertise and networks) to conduct research and generate knowledge regarding climate change and marine challenges and thus lack science-based data on which to base policy and create and test necessary adaptation and mitigation strategies [9,18]. To effectively support SIDS in enhancing their capacities to address sustainable marine development challenges that affect them, as highlighted by SDG 14.a, knowledge about their individual research infrastructures and capacities is urgently needed. In particular, in accordance with the statute of the IAEA, it is necessary to assess their research capacities and infrastructure for nuclear and isotopic science, as well as organic and inorganic geochemistry.

The goal of this work was to compile a capacity assessment, which summarizes the existing key research capacities in SIDS UN Member States to help formulate appropriate capacity development responses in marine areas of concern for SIDS. This study focuses primarily on the identification of marine environmental capacities with particular attention to nuclear and isotopic science, as well as inorganic and organic geochemistry facilities. This groundwork is important to ensure that the ocean science community, as well as national and international funding and development agencies, implement relevant and effective capacity development responses in SIDS UN Member States in the coming years to improve SIDS’s conditions for sustainable development of the ocean.

2. Overview of Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

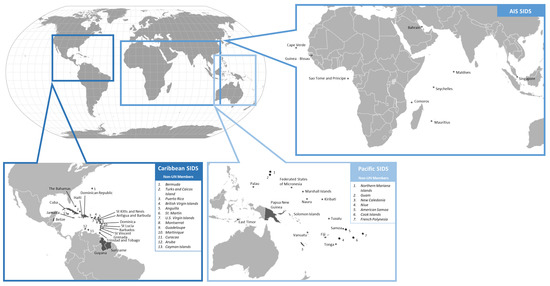

SIDS are a distinct group of 58 small island nations, low-lying countries, and territories situated in the tropics and low-latitude sub-tropics [14] across three geographical regions, i.e., the Caribbean; the Pacific; and the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and South China Seas (AIS) (Figure 1, Figure S1 and Table S2). The SIDS group comprises 38 UN Members and 20 Non-UN Members or Associate Members of Regional Commissions (Figure 1 and Table S2).

Figure 1.

Geographical regions of Small Island Developing States (SIDS). AIS: Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and South China Seas.

2.1. Physiographic and Environmental Characteristics of SIDS

2.1.1. Caribbean SIDS

The Caribbean region contains 29 SIDS, 25 of which lie in the tropics and four are located in the subtropical zone (Figure 1). Their geographical location makes the Caribbean SIDS vulnerable areas to the impact of natural hazards, such as hurricanes, storms, droughts, floods, landslides, volcanic activity, and earthquakes [19]. In total, 26 of the 29 SIDS are classified as islands and three are considered countries (Belize, Guyana, and Suriname). The Caribbean SIDS comprise a total of 1611 islands, islets, and atolls, cover a total land area of 599,105 km2 with a total coastline of 16,516 km (Table S4; [20]), and comprise a total maritime area of 3,750,019 km2 [21].

Inland water bodies (lakes, reservoirs, and rivers) cover a total area of 33,429 km2 (data missing for Guadeloupe and Martinique) with 16 SIDS having no or negligible freshwater sources (Table S4; [20]). The population in the Caribbean SIDS in 2018 amounted to a total of 44.3 million (average population density of 296 people/km2) with 4.2% of the population living in areas where elevation is below 5 m above sea level (Table S4; [20]). In particular, Suriname and Turks and Caicos Islands have >48% of their population living in areas below 5 m above sea level and thus both SIDS are assumed to be severely affected by future climate change. Further, in the Caribbean SIDS, 4.6% (data missing for Anguilla, Curacao, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Montserrat, and St. Martin) of the total land area is below 5 m of elevation above sea level, with the Bahamas (52.0%), Turks and Caicos Islands (55.9%), and the British Virgin Islands (28.0%) expected to be the most severely affected SIDS by climate change and associated sea level rise in the Caribbean (Table S4; [20]).

An average of 21.6% of the land area in Caribbean SIDS is used for agricultural purposes (i.e., land that is arable, under permanent/temporary crops, or under permanent/temporary pastures) and an average of 40.0% is covered in forest [20]. The coastal ecosystems in the Caribbean region are a mixture of mangrove, sea-grasses, and coral reefs [22], with the Caribbean SIDS containing 5.3% of the world’s coral reefs [21]. The Caribbean SIDS have a unique biodiversity and high levels of endemism with a total of 56,236 animal and plant species [23]. However, 3.5% of these species are currently classified as threatened, including a total of 172 bird species, 795 fish species, 100 mammal species, and 878 plant species as of 2018 [20,23]. Natural terrestrial and marine resources of commercial importance are limited, i.e., arable land (e.g., peanuts, tropical fruit), salt, seafood, petroleum, natural gas, timber, hydropower, and elements/minerals (e.g., limestone, cobalt, nickel, copper, gold, silver, phosphate; [19]). With the purpose to conserve the marine and terrestrial biodiversity and natural resources, the Caribbean SIDS protect, on average, 5.7% of their territorial waters and 6.9% of their terrestrial and marine areas as of 2018 [20], with St. Martin conserving as much as 96.4% of its territorial coastal and marine ecosystems.

2.1.2. Pacific SIDS

The Pacific region has 20 tropical SIDS (Figure 1), most of which are exposed to a large number of natural hazards, such as typhoons, storms, droughts, floods, landslides, volcanism, cyclones, earthquakes, tornadoes, and tsunamis [19]. Altogether, the Pacific SIDS have a land area of 555,572 km2, of which Papua New Guinea comprises 81.5%. The Pacific SIDS contain a total of 5019 islands, islets, and atolls and have a combined coastline of 31,541 km (Table S5; [20]). The territorial waters of the Pacific SIDS cover a total maritime area of 26,911.685 km2 [21].

Freshwater bodies cover a total area of 11,570 km2 with 14 of the 20 SIDS having no or negligible freshwater supplies (Table S5; [20]). The resident population of the Pacific SIDS in 2018 amounted to a total of 13.2 million (average population density of 163 people/km2) with 1.8% of the population living in areas where elevation is below 5 m above sea level [20]. In Pacific SIDS, 0.95% (data missing for Northern Mariana Islands, Cook Islands, Micronesia, and Nuie) of the total land area is below 5 m of elevation above sea level with Kiribati (54.6%), Marshall Islands (43.8%), and Tuvalu (32.6%) being the most severely affected SIDS by climate change and associated sea level rise in the Pacific region (Table S5; [20]).

On average, 23.3% of the land area in the Pacific SIDS is used for agricultural purposes and 53.3% is covered by forest [20]. The Pacific SIDS contain 21.4% of the world’s coral reefs and also have the world’s highest proportion of endemic species per unit of land area [22]. The biodiversity (a total of 40937 animal and plant species; [23]) is among the most critically threatened with 3.3% of species classified as threatened in 2018 including 195 bird species, 336 fish species, 108 mammal species, and 701 plant species [20,23]. To conserve the ecological biodiversity and the limited natural resources with commercial value (e.g., coconuts, fish, timber, pumice, minerals, hydropower, petroleum, and natural gas; [19]), Pacific SIDS put marine and terrestrial protected areas in place (on average 13.9% of their territorial area). As of 2018, marine protected areas (MPAs) covered on average 13.6% of the territorial waters of the Pacific SIDS with New Caledonia protecting as much as 96.6% of its territorial coastal and marine ecosystems [20].

2.1.3. Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and South China Seas SIDS

The Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and South China Seas (AIS) region consists of nine SIDS covering the tropical, arid, and temperate zones of the world (Figure 1; Table S6). Singapore is a member of the AIS SIDS category, though it is neither a small nor a developing state [18]. The geographical location makes the AIS SIDS high risk areas to the impact of natural hazards including typhoons, storms, droughts, harmattan winds, cyclones, fires, volcanic activity, earthquakes, and tsunamis [19]. The AIS SIDS include eight islands and one country (Guinea-Bissau), which together consist of a total of 1533 islands, islets, and atolls and cover a total land area of 39,248 km2 with a 3,530 km long coastline (Table S6, [20]). Guinea-Bissau is the largest SIDS in the AIS region, comprising 72% of the total land area. The maritime claim of each AIS SIDS gives the SIDS a total maritime area of 4,762,621 km2 [21].

Inland water bodies cover a total area of 8,025 km2 with six SIDS having no or negligible freshwater supplies (Table S6, [20]). In 2018, the AIS SIDS had a total population of 12.5 million (average population density of 1,487 people/km2), 13.8% of whom lived in areas where elevation is below 5 m above sea level [20]. The Maldives and Bahrain with 48.2% and 34.3% of their population living in areas < 5 m of elevation above sea level, respectively, are considered the most affected AIS SIDS by climate change. In general, 6.5% (data missing for Guinea-Bissau) of the total land area in AIS SIDS lies below 5 m of elevation, and again, the Maldives (45.5%) and Bahrain (34.0%) are considered the most impacted AIS SIDS regarding future sea level rise (Table S6, [20]).

Agricultural land covers on average 31.5% of the land area in the AIS SIDS, while on average another 33.6% of the land area is covered in forest [20]. The commercially valuable natural resources in the AIS region are limited to oil, natural gas, fish, timber, minerals, hydropower, and coconuts [20]. The AIS SIDS feature numerous marine ecosystems including mangroves and 10% of the world’s coral reefs [23]. The AIS region is extremely ecologically diverse and is home to a total of 16486 animal and plant species [23], of which 4.3% are classified as threatened as published by World Bank in 2019 (i.e., 99 bird species, 224 fish species, 59 mammal species, and 329 plant species). As of 2018, the AIS SIDS managed to protect various marine and terrestrial areas amounting to an average of 1.8% of their total territorial area with MPAs covering on average 1.3% of their territorial waters [20].

2.2. Economic Characteristics of SIDS

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) varies significantly among the SIDS. Singapore had the highest GDP in 2018 with US$ 307.9 billion, while Niue, with only US$ 10 million, had the lowest GDP [19,20]. Singapore, which is relatively rich by developing country standards, is often seen as the exception to the otherwise financially limited SIDS cluster [18]. The average GDP of the SIDS equals US$ 13.9 billion (2018), with the AIS SIDS having the highest average GDP with US$ 40.6 billion (US$ 14940 GDP per capita; AIS excluding Singapore: US$ 7.2 billion GDP and US$ 8735 GDP per capita), followed by the Caribbean SIDS with US$ 13.2 billion (US$ 21111 GDP per capita), and the Pacific SIDS with US$ 2.7 billion (US$ 8079 GDP per capita; Table 1; [19,20]). In total, 83% of SIDS have a GDP lower than the average of US$ 13.9 billion (no data for Guadeloupe and Martinique), and 37% have a GDP lower than US$ 1 billion (Table 1). The growth of most of the Caribbean (average GDP growth of 1.7%) and Pacific SIDS (average GDP growth of 1.6%) economies lagged largely behind the world average (3.0%) in 2018, while the AIS SIDS exceeded the world average with an annual GDP growth of 3.7% (AIS excluding Singapore: 3.8%) in the same year [20].

Table 1.

Economic data of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) [20].

The tourism industry (direct contribution via the travel and tourism sector and indirect contribution via the services sector, which includes hotels and restaurants) is a vital economic sector for the development of SIDS in terms of GDP earnings and employment (Figure S2; [20,24]). For instance, the Maldives are highly dependent upon revenue gained from tourism, with 38.9% of the island’s GDP coming from the travel and tourism sector (Table 1). Other important sectors for the SIDS economies are industry and agriculture (including forestry and fishing) with the latter contributing on average 4.9%, 15.6%, and 11.6% to the GDP in the Caribbean, Pacific, and AIS SIDS, respectively (Table 1 and Figure S2).

Additionally, SIDS rely heavily on trade to drive economic growth [24] with contributions of the export and import of goods and services to the GDP being far higher for SIDS than the global average (Figure S3 and Table 1). The fact that SIDS are dependent on tourism, have a narrow resource base, are usually single commodity exporters which greatly rely on export earnings, and are remote from international markets increases their vulnerability to external economic threats and shocks as well as the impacts of natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, landslides, tropical storms, floods, and droughts) and climate change [14,24].

Indeed, SIDS are located among the most vulnerable regions in the world in relation to the intensity, frequency, and increasing impact of natural disasters and thus face disproportionately high economic, social, cultural, and environmental consequences [24]. The overall costs of disasters and the economic losses resulting from the negative effects of natural disasters are significant for SIDS and can set back economic development gains by several years [24,25]. For instance, an earthquake in Haiti in 2010 destroyed the equivalent of 120% of Haiti’s GDP [20,26], and Hurricane Matthew, which struck the country in 2016, caused damage estimated to equal 32% of Haiti’s GDP [26,27,28]. However, economic losses vary among SIDS, with Caribbean SIDS predicted to face on average the highest annual loss by 2030 as a share of cumulative GDP with 6.3%, followed by the Pacific SIDS with 3.9%, and the AIS SIDS with 0.1% [20,29,30].

The risk of economic breakdown, extensive environmental damage, and disruptions of social and cultural processes in SIDS is only expected to grow owing to climate change [13]. Although the SIDS are among the least responsible for climate change, contributing less than 0.6% (as of 2012) to the global greenhouse gas emissions [20], they are likely to suffer the most from its adverse effects such as sea level rise, extreme storm events and droughts, increasing sea surface temperatures, ocean acidification, coral bleaching, inundation, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem destruction [25]. The socio-economic implications of sea level rise in particular will have drastic negative impacts on all important economic sectors of SIDS including tourism, financial services, agriculture, fisheries, water supply and sanitation, infrastructure, and ecosystem health [25]. For instance, protecting Jamaica’s coastline from impacts of a sea-level rise of 1 m is estimated to cost US$ 462 million annually—19% of the country’s GDP [13]. Globally, estimated economic stresses due to climate change project losses of US$ 70–100 billion per year through to 2050 [20].

In addition to natural disasters, external economic shocks can also have drastic impacts on financial markets and institutions in SIDS and can cause significant economic, social, and political disruption. For instance, the emergence of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, highlighted the global economic vulnerability to epidemics and pandemics, placing a disproportionally higher burden on LDC and SIDS due to their dependency on international trade and foreign tourism whose demand has collapsed [31]. On average, trade and tourism (indirectly and directly) account for more than 71% and 30%, respectively, of SIDS GDP, and a decline in tourists by 25% will result in a $7.4 billion or 7.3% fall in SIDS GDP [31]. According to the UN/DESA brief Nr. 64 [31], the projected GDP growth rate of SIDS will likely shrink by 4.7% in 2020, compared to a global contraction of around 3.0%, which will exceed the economic impact of some natural disasters, such as tropical hurricanes. These estimates are, however, rather conservative, and the drop in GDP could be significantly greater in some of the SIDS [31]. The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic will be devastating for many of the SIDS with long lasting effects, which will have major implications for 1) withstanding future natural disasters, and 2) achieving global and national targets within the 2030 agenda and the SDGs [31]. This pandemic underscores the extreme vulnerability of SIDS to global economic shocks and thus further highlights the need of SIDS for international assistance and cooperation.

3. Commonalities of SIDS—Marine Challenges

The data above show that SIDS are geographically dispersed and have diverse ecological and cultural characteristics as well as social and economic structures (i.e., island—non-island, developing—non-developing, states—non-states). Nevertheless, they face similar social, economic, and environmental challenges [14]. Their inherent challenges stem from factors such as their small size, geographical remoteness, narrow resource base, low-lying coastal territories, concentration of the population along coastal zones, growing populations, high volatility of economic growth, dependency on external markets and international assistance, susceptibility to natural disasters (i.e., cyclones and earthquakes), and high vulnerability to the impacts of a changing climate [14,32]. Of particular concern to SIDS are the marine challenges associated with climate change and anthropogenic activity.

Climate change and anthropogenic activities threaten marine ecosystems, economies, and communities on a global scale, but with local consequences. Some impacts are already evident, but other impacts and effects will only become an issue in the coming decades when biological tipping points and thresholds are reached and the resilience of marine ecosystems can no longer be maintained. Climate change and anthropogenic activities are putting the oceans and thus the provision of their ecosystem services at risk. These pressures have a disproportionately greater impact on SIDS, where oceans and marine resources tend to play a fundamental role in financial, social, cultural, and environmental wellbeing [12,14,33]. The most pressing marine issues for SIDS are listed in Table 2, separated into three key themes, with no particular order of priority.

Table 2.

List of the most pressing marine issues for Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

All of the current and emerging marine environmental challenges have strong social and economic components, particularly in SIDS which are acutely dependent on oceans. Accordingly, the marine challenges of SIDS should be viewed in a holistic and integrative manner since any changes to any one of these sectors could ultimately lead to the collapse of another [12,25].

However, despite their similar challenges, SIDS do not easily fit into standard response and solution models since each SIDS prioritizes different marine challenges in the context of its unique geophysical characteristics (vulnerabilities), social, economic, and environmental needs, adaptive capacities, and sustainable commitments [12,34,35]. For instance, natural hazards produce widely different outcomes in different countries—while some SIDS seem to cope and adapt fairly well, others suffer tremendously [35]. These differences have to be recognized, understood, and addressed for sustainable development to be suitably realized in SIDS on a national level. Therefore, capacity building, solutions, and adaptive strategies for marine challenges in SIDS need to be custom tailored for each individual SIDS.

4. The Way Forward—Needs to Tackle the Challenges

Despite the specificities of each SIDS, several commonalities regarding possible appropriate and practical responses to address the marine challenges of the 21st century can be identified and are listed below [12,36,37]. These recommendations should be addressed by a broad participation of all relevant stakeholders across different spatial scales and frameworks [9], i.e., international and national governments and agencies, regional and sub-regional organizations, educational and academic entities, and local communities, including multi-stakeholder partnerships, to provide the best chance of long-lasting solutions.

- Define Indicators—Identify a manageable set of measurements (proxies and indices), which are globally applicable to evaluate ecosystem health in various regions in order to reduce cost and time; engage government entities, donors, funding agencies, and the public; as well as allow the interoperability of research data. Frameworks such as the Ocean Health Index [38] can be used in SIDS to assess ocean health and thus inform policy and evaluate progress.

- Establish Protocols and Standards—Standards and protocols for sample collection, handling, analysis, and data products are needed to obtain high quality data, meet global standards, and allow the interoperability and reproducibility of research data. For this, SIDS can take advantage of repositories such as the Ocean Best Practices System (OBPS; [39]), which includes standard operating procedures, manuals, and method descriptions for most ocean-related sciences and applications.

- Establish Baseline Measurements—Establish monitoring programs or engage with existing monitoring programs such as the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON; [40]) to quantify baselines and detect changes in the biogeochemistry of water bodies to evaluate ecosystem health. These data are needed to inform policy-makers and thus support better decision making on management strategies.

- Create Data Reporting Networks—Create data products, reporting networks, and mechanisms to share scientific findings and lessons. Herein, SIDS can take advantage of the Ocean Data and Information System Catalogue (ODIS, [41]) to find ocean-related web-based data products or participate in existing networks such as the Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre (OA-ICC; [42]) and the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS, [43])

- Improve Local Modelling Projections—Advance the resolution of existing scenario models to help identify and address local priorities and issues.

- Advance Scientific Understanding—Conduct national/regional vulnerability assessments to identify the potential impact of climate change and anthropogenic activity on key ecological, cultural, and economic marine resources and species, as well as the communities that depend on them.

- Optimize Research—Enhance the research capacity and infrastructure by developing low-cost instrumentation and secondary standards to reduce costs and help SIDS to gather, access, and use data to take ownership in capacity building activities and decision-making. There is also a necessity to make pre-existing technology (e.g., autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs); Argo floats; conductivity, temperature, and depth instruments (CTDs); Gliders; Monitoring Buoys etc.) globally available to obtain relevant data for effective adaptation, mitigation, and resilience strategies.

- Take Meaningful Actions and Implement Solution-based Strategies—Reduce the causes of climate change and anthropogenic activity by implementing effective mitigation, resilience, and adaptation strategies, tailored to local and regional needs and priorities. Some marine problems can be circumvented with human interventions, e.g., reduction of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, solar radiation management, protection of biota and ecosystems, and manipulation of biological and ecological adaptation [44]. One example of an effective climate change action is championed by the Blue Carbon Initiative [45] which aims to mitigate climate change through the restoration and sustainable use of coastal and marine ecosystems such as mangroves, tidal marshes, and seagrasses. The success of existing and emerging management strategies has to be validated and quantified with scientific means. Networks such as EVALSDGs [46], the International Organization for Cooperation in Evaluation (IOCE; [47]), and Eval4Action [48] can support SIDS to effectively evaluate efforts on the timely delivery of SDGs to guide evidence-based decision-making.

- Raise Public Awareness—Inform and educate the wider public about current and emerging local marine challenges and their impacts on social, environmental, and economic security to develop local awareness, expertise, knowledge, and thereby drive action. Initiatives such as UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) program [49] and the Sandwatch program [50] can support regional efforts in SIDS via climate change education.

While some SIDS lack the capacity to act on the above-mentioned recommendations, others such as the Pacific SIDS already have ocean observation processes in place, thanks to national and international support and close collaborations between governments. However, overall, SIDS remain dependent on the support of developed countries to help them establish, gather, access, and use data to build their capacity regarding monitoring activities, sustainable development, and decision-making processes [9,12]. Thus, the increase in national scientific knowledge including long-term education, training, and human resource development, as well as the improvement of national research capacities, and the transfer of marine technology has to be the fundamental purpose of capacity building efforts to help SIDS to help themselves with long-lasting effects. The development of knowledge and skills relevant in the design, development, implementation, management, and maintenance of institutional and scientific infrastructures is key to ensure local ownership and thus the achievement of nationally relevant SDGs. Multilateral organization such as SCOR [51], GEOTRACES [52], GOA-ON [53], and the IAEA [54] are involved in capacity building activities for ocean science and can help SIDS to build capacity via resources, technical guidance, scientific mentorship, training, workshops, summer schools, scholarship, and financial support. Capacity building is also provided by regional actors in SIDS such as the Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA; [55]), the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP; [56]), and the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (CCCCC; [57]), just to name a few. In particular, universities in SIDS will be central players in national capacity building activities, since they are the generators of knowledge, sources of trained personnel, and hubs of innovation [16]. After successful capacity development efforts, effective approaches have to be found and implemented to retain human resources (i.e., trained people) in SIDS. This retention is so far a problem in most developing states, where often people that receive capacity building training leave their institutions and organizations afterwards because of better employment opportunities due to their newly acquired skills. Thus, capacity building is quickly lost again.

For institutional, research, and human capacity building activities to be effective in suitably realizing sustainable development in SIDS on a national level, we believe that it is necessary to take the following factors into account:

- Coordination and facilitation of capacity building at a national and sub-national level—To empower national ownership and local leadership, the involvement of stakeholders at the national level is necessary to understand national capacity needs, define and shape the national capacity building agenda, and subsequently guide and coordinate appropriate national capacity efforts. Coordinated governmental bodies, agencies, and institutions, with clearly defined responsibilities and duties, are a requirement to effectively and efficiently guide, navigate, and facilitate the implementation and management of capacity building efforts and SDGs without duplication and fragmentation [16]. Herein, the Ocean Action Hub platform [58] and organizations such as GOA-ON [40] can be used to support SIDS in creating web-based and regional science hubs to facilitate multi-stakeholder engagement in order to address regional challenges, needs, and priorities as a collective.

- Enhancementof Collaboration and Coordination—Bridging the gap between scientists, communities, and policy makers is an essential component to increase awareness and understanding of marine risks and to develop mitigation and adaptation responses and resource management strategies targeted to local priorities. Further, there is a need for more sustainable and effective international partnerships and collaborations between and among developed and developing nations to build capacity, transfer technology, link initiatives, share networks, and mobilise resources. International organizations such as the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO (IOC-UNESCO; [59]) and The Ocean Foundation [60] can help SIDS to facilitate dialogue among stakeholders and further catalyse partnerships among scientists, policymakers, academia, businesses, industry, and the public.

- Increase Sustained Financial Support—Develop coordinated funding strategies and identify existing or potential funding sources that will help complement regional long-term actions such as research, monitoring, and outreach activities. There is a strong need for long-term funding in SIDS to support ongoing costs of analysis centers (e.g., maintenance, staffing, quality control, standard solutions, and consumables) and to guarantee efficient monitoring efforts and outputs relevant to improve and inform modelling predictions, national strategies, and policy. There are many regional and multi-lateral funding opportunities available for SIDS including those endorsed by the World Bank’s Global Environment Facility (GEF), the EU’s Advancing Capacity to support Climate Change Adaptation project, the Asian Development Bank, the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), and most recently the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

Applied and basic marine research plays a strategic and important role in SIDS to move forward and identify, solve, and manage marine problems, particularly those related to SDG 14.1 to 14.5. Capacity building in science is, among others, an essential component in the process of achieving sustainable ocean and coastal development both at national and international levels [36]. However, most SIDS have limited infrastructure; technical and institutional capacity; financial, human, and material resources; as well as a lack of expertise and networks needed to produce scientific information to adequately develop and implement national plans in the context of international agreements [12,36]. To effectively support SIDS to address and overcome nationally-identified marine challenges and promote, develop, and strengthen marine science, sustainable and long-term regional capacity building and research infrastructure programs are key [12,36]. However, for stakeholder efforts to be effective in supporting individual SIDS in enhancing their capacities and capabilities to address their sustainable marine development priorities (developed in line with SDG 14.a), knowledge about their individual capacity building and research infrastructure requirements is necessary. Accordingly, an updated capacity assessment of human resources as well as institutional and technical capacities in each SIDS are needed to create suitable information for future program conception, implementation, execution, and evaluation.

5. Research Infrastructure and Capacities in UN SIDS

The following capacity assessment, which summarizes the existing key capacities in SIDS UN Member States, can be used as a basis to formulate appropriate capacity development responses by the international ocean science community, national governments, as well as funding and development agencies. Data are pooled from online databases including the World Bank [20] for data on national research and education expenditures as well as data on scientific publications, the World Higher Education Database [61] and the Commonwealth Network [62] for data on tertiary education institutions, and the UNESCO Data for Sustainable Development Explorer [63] for data on human resources in research and development. The authors acknowledge the fact that the paper is not a comprehensive analysis of the scientific capacity and capability of SIDS UN Member States in ocean sciences, but is rather a suitable starting point from which it is possible to gain a preliminary and useful insight into current research infrastructures and capacities in SIDS UN Member States. It should also be considered as the initial input of a publicly available and accessible database, future implementation of which we submit as a recommendation. It is also important to bear in mind that the capacity assessment and associated conclusions are limited by the information given on the above-mentioned websites (including the websites of each respective institution, Table S7). Accordingly, the capacity assessment omitted a discussion on research infrastructures and capabilities in SIDS Non-UN Members or Associate Members of Regional Commissions since there are only limited data available.

On average, the government in SIDS UN Member States invests approximately 14.5% of the total government expenditure on general education (European Union, 12.0%; North America 13.4%), and 14.7% of this total government expenditure for general education is invested in tertiary education (European Union, 22.0%; North America 28.0%). In regional terms, most SIDS make similar educational investments, but there are significant differences for some SIDS (Table 3; [20]). Data for research and development expenditure (% of GDP) are only available for some SIDS UN Member States, but usually the amount does not exceed 0.4% of the GDP, except for Singapore (Table 3; [20]), and is thus well below the research and development expenditures (% of GDP) of the global scientific powerhouses, particularly the United States (2.8%), China (2.2%), United Kingdom (1.7%), and Germany (3.0%) [20].

Table 3.

Education and research capacity data of UN Small Island Developing States (SIDS) [20].

The lack of expenditure on research and development and thus the low capacity to do research in Natural Sciences in SIDS UN Member States is also highlighted by the low output of scientific and technical articles (fields: physics, biology, chemistry, mathematics, clinical medicine, biomedical research, engineering and technology, and earth and space sciences; [20]) published in 2016 by SIDS UN Member States—they contributed only 0.6% (Caribbean SIDS: 0.07%, Pacific SIDS: 0.01%, and AIS SIDS: 0.51%; AIS excluding Singapore: 0.02%) of all the scientific and technical articles published worldwide in 2016 (Table 3; [20]).

Data on human resources in SIDS UN Member States are limited and barely up-to-date. Most SIDS suffer from the limitation of a small population and thus their national technical and research capacity is usually very low [38]. For instance, in Bahrain and Papua New Guinea, the number of researchers and technicians engaged in research and development, expressed as per million people, was 367 (2014) and 47 (2016), respectively, while it was 7187 (2014) in Singapore [20]. Consequently, SIDS experience great difficulties in developing local expertise to meet the wide-ranging and growing demands of national and regional marine sustainable development [64].

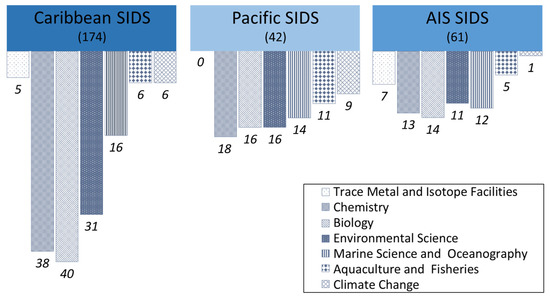

As of 2019, according to the World Higher Education Database and the Commonwealth Network, there are altogether 277 tertiary education institutions (i.e., universities, polytechnics, and colleges, including associated scientific institutes and centers) in the SIDS UN Member States and only 14 out of these 277 institutions disclose information (on their respective websites) regarding their scientific facilities and capacities. Twelve out of these 14 institutions (five in the Caribbean SIDS and seven in the AIS SIDS, six of which are located in Singapore) report on their facilities, infrastructures, and instrumentation to perform nuclear and isotopic techniques and organic and inorganic geochemistry (Figure 2 and Table S7). However, these values may not reflect the actual overall stage of development of marine science capabilities in SIDS given that the data were obtained from the websites of each respective institution and some of those websites do not disclose information regarding their scientific facilities, capabilities, and capacities or are particularly difficult to navigate. Thus, these figures have to be seen as ‘minimum values’ since they rely heavily on available statistics and the reporting mechanisms in place, which are usually insufficient in SIDS due to constraints in the human, technical, and financial resources required for generating this kind of information [9]. These values highlight that reporting mechanisms on marine science capacities in SIDS have to be put in place to aid in the development and implementation of relevant, effective, and successful capacity development responses in SIDS in order to improve their conditions for sustainable development of the ocean [9].

Figure 2.

List of existing tertiary institutional capacities in UN Small Island Developing States (SIDS). The numbers in the parentheses at the top represent the number of existing tertiary education institutions in each respective SIDS region. Note that these data are limited by the information given on the website of each respective institution.

Up to 69, 70, and 58 SIDS UN Member State institutions currently teach courses or offer diplomas and certificates in Chemistry, Biology, and Environmental Science, respectively (Figure 2 and Table S7), and thus have the potential to put infrastructure in place (if not already existing) to conduct research necessary to deliver on regional and national environmentally focused SDGs. Furthermore, up to 40%, 21% (10% excluding Singapore) and 11% of Pacific, AIS, and Caribbean SIDS UN Member State institutions already offer courses and diplomas in Marine Science, Oceanography, Aquaculture, Fisheries, and Climate Change (Figure 2 and Table S7), and, therefore, possibly already address, monitor, and tackle national issues identified under SDG 14 (Life Below Water).

The Caribbean SIDS possess the highest tertiary institutional capacities and capabilities in SIDS regions, followed by the AIS and Pacific SIDS. This order might be surprising at first considering that the Caribbean SIDS have the lowest percentage of total government expenditure on tertiary education, but they do have the largest GDP per capita and the highest population (up to 3.5-fold) of the three SIDS regions and thus a higher demand for institutional capacities. The AIS SIDS, even though they have the lowest total population, find themselves ranked in the middle, between Caribbean and Pacific SIDS, regarding their amount of current tertiary institutional capacities and capabilities. This result is largely explained by Singapore, since education has been a key driver in Singapore’s economic development over the last decades [65,66]. Singapore’s aspirations to be a global education hub lead to large investments in the establishment and expansion of state-of-the-art campuses, centers, research laboratories, and joined degrees with international top-ranking universities [65,66]. The Pacific SIDS have the lowest amount of tertiary institutions, but considering their low GDP (15 times lower in relation to AIS SIDS), their institutional capacities are promising. In addition, up to 40% of the institutions in the Pacific SIDS engage in Marine Science-related topics compared to only 11% in the Caribbean SIDS and 21% (10% excluding Singapore) in the AIS SIDS. This outcome could be attributed to the fact that Pacific SIDS have the largest coastline and maritime area and contain the highest percentage of coral reefs and marine protected areas out of the three SIDS regions and thus have a higher need for stewardship of coastal and marine resources. In general, therefore, it seems that the Pacific SIDS are currently the leaders in ocean science-related research capacities and infrastructures in SIDS regions.

6. Conclusion and the Way Forward

The research capacities and capabilities in SIDS are heterogeneous, and some countries will need more help and funding than others to reach international standards. Despite some progress made in the last few years, if SDGs are to be met by SIDS in the next 10 years and if SIDS are to engage productively with international agendas in order to formulate and solve their own priorities it is necessary for SIDS to 1) have an educational shift toward relevant nationally-identified environmental issues, and 2) strengthen research capacities in light of each SIDS’s distinctive social, cultural, economic, and environmental challenges. These measures should be supported by international, national, and regional collaborations and partnerships via funds and systematic capacity building which focuses on strengthening national self-determination and ownership [67]. Durable partnerships, based on mutual collaboration, ownership, trust, respect, accountability, and transparency, will be the means for achieving ocean sustainable development via concerted capacity building efforts. However, despite the urgency for SIDS to strengthen their research capacities and infrastructures, ways to achieve this have yet to be fully and critically explored. Nevertheless, there appears to be a consensus that capacity building must include individuals, institutions, and systems that collectively enable effective and sustainable development [16]. Yet, the way forward will still vary for each individual SIDS, dependent on the current state of research and education infrastructure, as well as social, cultural, economic, and environmental priorities.

The importance of relevant and durable research capacity and infrastructure in SIDS has been recognized globally, and regional, national, and international organizations, both past and present, including the UN, have accorded priority to this area, as reflected by SDG 4 (Quality Education). However, the current assessment highlights the fact that there is only limited, if any, up-to-date information publicly available on the number of researchers and technicians engaged in research and development in individual SIDS, and institutional websites commonly lack appropriate information on respective programs and institutional facilities. These limitations make it challenging to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the scientific capacity and capability of SIDS UN Member States to help national and regional policymakers as well as international agencies, programs, and projects to formulate appropriate national and international capacity development responses in, and for, SIDS. The current assessment is a suitable starting point from which it is possible to gain preliminary and useful insight into current research infrastructure and capacities in SIDS UN Member States, but considerably higher amounts of data are necessary to establish a greater degree of understanding of the current state in SIDS—How should we know where to start if we do not know where to start from?

To formulate appropriate national and international capacity development responses (e.g., funding, collaborations, partnerships, and resource management) to achieve SDGs in SIDS, an up-to-date database on educational, institutional, human, and research capacities is necessary. In other words, a bottom up approach is indispensable—a complete database will lay the foundation to provide adequate information on national and regional research capacities, gaps, and requirements. This information in turn will allow regional, national, and international parties to develop and implement durable, relevant, effective, and successful development responses, tailored to local and regional needs and priorities of each SIDS, to deliver on the SDG 14 as individuals and as a collective. To support efforts to create an ocean-related database, the current assessment highlights four key measures:

- (1)

- Collect data—Gather more data on human resources, research infrastructures, and institutional capacities and facilities to create regional information baselines. In this connection, it is important that the public websites of institutions have easily-navigated site maps and include up-to-date information on institutional research facilities and capabilities. Regional initiatives (i.e., WIOMSA, SPREP, and CCCCC) will also be key in gathering and updating capacity information outside the tertiary environment and in carrying out activities to improve it.

- (2)

- Put data networks in place—Data on research capacities, capabilities, and infrastructures have to be made publicly available and easily accessible via data products and networks to share data and thus inform governments, policymakers, and the international community to support better decision making. The current lack of information sharing and accessibility is supported by the fact that the IAEA’s TC Programme supports 23 SIDS, 14, 5 and 4 of which are situated in the Caribbean, Pacific, and AIS region, respectively, but as of yet only 12 SIDS report on available research capacities and infrastructures for nuclear and isotopic science, including organic and inorganic geochemistry.

- (3)

- Identify metrics—Reliable assessment procedures and metrics have to be put in place to evaluate the progress of capacity building efforts and serve as an analytical base to understand patterns and determinants of successful capacity building programs [16]. Frameworks such the Capacity Building Initiative for Transparency (CBIT; [68]) under the UNFCCC can help SIDS to track and report progress of existing and future country commitments.

- (4)

- Increase sustained funding and expertise—The previously listed measures can only be realized if appropriate access to funding and expertise is put in place. The required financial resources are unlikely to be met from national government budgets since the lack of funding and expertise is the single major impediment in SIDS to sustainably carry out sustainable marine development in the first place [12]. Therefore, the long-term provision of financial resources and capacity building in SIDS must be sought through international and intergovernmental cooperation (lending/funding/donor/aid agencies) to enable SIDS to become equal partners in dealing with global economic and environmental issues [10].

Creating databases on research capacities and infrastructures in SIDS UN Member States will allow these states to develop and successfully implement appropriate development responses to the most urgent present and future national needs on ocean and coastal environmental issues. Long-term, durable, and appropriate capacity responses are decisive for the future of each region [9] and thus should form fundamental strategies to achieve social, cultural, political, economic, and environmentally sustainable development.

It is undeniable that national, regional, and international efforts have already led to an important and considerable improvement in SIDS capacities, both at regional and national levels. However, continued and long-term action is required to cope with the expected increase in the severity of climate-related impacts on ocean systems and services [44,69]. Multilateral programs, such as the Decade and the ongoing IAEA TC Programme, can play a major role in promoting ocean science, catalyzing action, facilitating cooperation, supporting networking forums, and providing capacity development, expertise, and resources in SIDS. The TC Programme for example, can act as a catalyzer, with an advisory, coordinative, and facilitating role to use nuclear science and technologies to address marine challenges, such as coastal zone management, impacts of climate change (e.g., ocean warming and ocean acidification), marine biodiversity loss, seafood safety and trade, food security, water resource management, coastal and marine pollution, harmful algal blooms, marine biotoxins, and sustainable aquaculture [70]. Presently, these marine threats are all areas of concern for SIDS. But more importantly, the IAEA can respond to the need for a database on research capacities and infrastructures in SIDS UN Member States by acting as a hub to develop, facilitate, coordinate, and lead such a data portal, as previously done via the IAEA’s Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre (OA-ICC) after concerns from UN Member States about ocean acidification in 2012. Only a concerted capacity building effort and action by international, national, and regional parties will allow the furthest behind to catch up and become an equal partner in addressing global ocean sustainable development and management.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2673-1924/1/3/9/s1, Figure S1: Geographical regions of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Figure S2: Average composition of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Small Island Developing State (SIDS) regions by sectors as of 2017/2018, Figure S3: Average imports and exports as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by Small Island Developing State (SIDS) regions, Table S1: Targets of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14—Life Below Water, Table S2: List of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) separated into UN Members and Non-UN Members/Associate Members of Regional Commissions, Table S3: List of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) that participate in the Technical Cooperation (TC) Programme of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Table S4: List of physiographic data of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Caribbean region, Table S5: List of physiographic data of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Pacific region, Table S6: List of physiographic data of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and South China Seas (AIS) region, Table S7: List of existing tertiary education institutional capacities in UN Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.P., P.W.S. and R.Z.; methodology, R.Z.; formal analysis, R.Z.; investigation, R.Z.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.Z., S.P.P, P.M., S.G.S. and P.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded under the IAEA Interregional Project INT0093 “Applying Nuclear Science and Technology in Small Island Developing States in Support of the Sustainable Development Goals and the SAMOA Pathway”.

Acknowledgments

R.Z. thanks W.D.N. Dillon from the University of Otago for his help with the edits of the final draft and for valuable discussions regarding the concepts presented in this manuscript. P.W.S. appreciatively recognizes the continued support provided by the IAEA Environment Laboratories and the IAEA Technical Cooperation Programme. The IAEA is grateful for the support provided to its Environment Laboratories by the Government of the Principality of Monaco. This work contributes to the ICTA ‘‘Unit of Excellence’’ (MinECo, MDM2015-0552).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UN. Draft Outcome Document of the United Nations Summit for the Adoption of the Post-2015 Development Agenda. In Draft Resolution Submitted by the President of the General Assembly, Sixty-Ninth Session, Agenda Items 13 (a) and 115, A/69/L.85, August 12, 2015; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.; Neumann, B.; Waweru, Y.; Durussel, C.; Unger, S.; Visbeck, M. SDG14 Conserve and Sustainably Use the Oceans, Seas and Marine Resources for Sustainable Development; International Council for Science: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ntona, M.; Morgera, E. Connecting SDG 14 with the other Sustainable Development Goals through marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturesson, A.; Weitz, N.; Persson, Å. SDG 14: Life below Water. A Review of Research Needs. In Technical Annex to the Formas Report Forskning för Agenda 2030: Översikt av Forskningsbehov och Vägar Framåt; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.G.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Swartz, W.; Cheung, W.; Guy, J.A.; Kenny, T.A.; McOwen, C.J.; Asch, R.; Geffert, J.L.; Wabnitz, C.C.; et al. A rapid assessment of co-benefits and trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visbeck, M. Ocean science research is key for a sustainable future. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IOC. The Science We Need for the Ocean We Want: The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030); IOC Brochure 2018-7 (IOC/BRO/2018/7 Rev); IOC: Paris, France, 2019; 24p. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, E.R.; Bowie, A.R.; Boyd, P.W.; Buck, K.N.; Lohan, M.C.; Sander, S.G.; Schlitzer, R.; Tagliabue, A.; Turner, D. The Importance of Bottom-Up Approaches to International Cooperation in Ocean Science. Oceanography 2020, 33, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, L. Global Ocean Science Report: The Current Status of Ocean Science around the World; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Small Island Developing States. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sids/list (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UN. LDCs at a Glance. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category/ldcs-at-a-glance.html (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Kullenberg, G. Capacity building in marine research and ocean observations: A perspective on why and how. Mar. Policy 1998, 22, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Climate Change, Small Island Developing States; Climate Change Secretariat (UNFCCC): Bonn, Germany, 2005; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- UN-OHRLLS. Small Island Developing States in Numbers; Climate Change Edition; UN-OHRLLS: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- SAMOA Pathway. SIDS Accelerated Modalities of Action Outcome Statement. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/69/15&Lang=E (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Khan, M.; Sagar, A.; Huq, S.; Thiam, P.K. Capacity building under the Paris Agreement; European Capacity Building Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IAEA. How Nuclear Techniques Help Address Environmental Challenges of Island States; IAEA Brief Environment 2017/4; IAEA Brief Environment: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baldacchino, G. Seizing history: Development and non-climate change in Small Island Developing States. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Factbook; Central Intelligence Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/index.html (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- World Bank. World Development Indicators; The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Pauly, D.; Zeller, D. (Eds.) Sea around Us Concepts, Design and Data. 2015. Available online: http://www.seaaroundus.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Al-Jenaid, S.; Chiu, A.; Dahl, A.; Fleischmann, K.; Garcia, K.; Graham, M.; King, P.; Kubiszewsk, I.; McManus, J.; Ragoonaden, S.; et al. GEO Small Islands Developing States Outlook; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2019-2; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Boto, I.; Biasco, R. Small Island Economies: Vulnerabilities and Opportunities; Brussels Rural Development Briefings. A series of meetings on ACP-EU development issues; CTA Brussels Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. GEO Small Island Developing States Outlook; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelin, L.H.; Cela, T.; Shultz, J.M. Haiti and the politics of governance and community responses to Hurricane Matthew. Disaster Health 2016, 3, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OCHA. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Haiti: Hurricane Matthew Situation Report no. 19. 2016. Available online: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ocha_haiti_sitrep_19_02_nov_2016_eng.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Taft-Morales, M. Haiti’s Political and Economic Conditions: In Brief. 2017. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/caa7/3af7dddfbd334ee753bf7d3f6ba97781c129.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNSD. UN Statistics Division. 2019. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/home/ (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- EM-DAT. The International Disaster Database. 2019. Available online: https://emdat.be/ (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- UN/DESA. UN/DESA Policy Brief #64: The COVID-19 Pandemic Puts Small Island Developing Economies in Dire Straits. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-64-the-covid-19-pandemic-puts-small-island-developing-economies-in-dire-straits/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Wong, P.P. Small island developing states. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMEP. Pacific Marine Climate Change Report Card 2018; Bryony, T., Paul, B., Jeremy, H., Tommy, M., Sylvie, G., Awnesh, S., Gilianne, B., Patrick, P., Sunny, S., Tiffany, S., Eds.; Commonwealth Marine Economies Programme: London, UK, 2018; 12p.

- Nurse, L.A.; McLean, R.F.; Agard, J.; Briguglio, L.P.; Duvat-Magnan, V.; Pelesikoti, N.; Tompkins, E.; Webb, A. Small islands. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1613–1654. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstedt, M.; Povitkina, M. Vulnerability of Small Island Developing States to Natural Disasters: How Much Difference Can Effective Governments Make? J. Environ. Dev. 2017, 26, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, G.G. The Caribbean: Main experiences and regularities in capacity building for the management of coastal areas. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2002, 45, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Tenth Session, Held at Buenos Aires from 6 to 18 December 2004. Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop10/10a01.pdf#page=7 (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Ocean Health Index. About Ocean Health Index. Available online: http://www.oceanhealthindex.org (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Ocean Best Practices Ocean Best Practices System. Available online: www.oceanbestpractices.org (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- GOA-ON. About GOA-ON. Available online: http://www.goa-on.org/home.php (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- ODIS. Ocean Data and Information System “Catalogue of Sources”. Available online: https://catalogue.odis.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- OA-ICC. IAEA Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre (OA-ICC) portal for ocean acidification biological response data. Available online: http://oa-icc.ipsl.fr/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- GOOS. Framework for Ocean Observing. Available online: https://www.goosocean.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Gattuso, J.P.; Magnan, A.K.; Bopp, L.; Cheung, W.W.; Duarte, C.M.; Hinkel, J.; Mcleod, E.; Micheli, F.; Oschlies, A.; Williamson, P.; et al. Ocean solutions to address climate change and its effects on marine ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Blue Carbon Initative. About Blue Carbon. Available online: https://www.thebluecarboninitiative.org/about-blue-carbon (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- EvalPartners. EvalAgenda2020. Available online: https://www.evalpartners.org/about/about-us (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- IOCE. About the International Organization for Cooperation in Evaluation (IOCE). Available online: https://www.ioce.net/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Eval4Action. The Decade of Evaluation for Action. Available online: https://www.eval4action.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNESCO ESD. Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNESCO. SANDWATCH: A Science Education Scheme through Sustainable Coastal Monitoring. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/priority-areas/sids/sandwatch/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- SCOR. Capacity Development. Available online: http://scor-int.org/work/capacity/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- GEOTRACES. GEOTRACES Capacity Building Activities. Available online: https://www.geotraces.org/geotraces-capacity-building-activities/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- GOA-ON. Pier2Peer. Available online: http://www.goa-on.org/pier2peer/pier2peer.php (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- IAEA. Training Courses. Available online: https://www.iaea.org/services/education-and-training/training-courses (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- WIOMSA, About Western Indian Ocean Marine Science Association (WIOMSA). Available online: https://www.wiomsa.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- SPREP. About The Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). Available online: https://www.sprep.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- CCCC. The Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre—Empowering People to Act On Climate Change. Available online: https://www.caribbeanclimate.bz/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNDP About the Ocean Action Hub. Available online: https://www.oceanactionhub.org/about-ocean-action-hub (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNESCO-IOC. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC). Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/ioc-oceans/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- The Ocean Foundation. About The Ocean Foundation. Available online: https://oceanfdn.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- WHED. IAU the World Higher Education Database (WHED). Available online: https://www.whed.net (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Commonwealth Network. Commonwealth in Action. Available online: http://www.commonwealthofnations.org/commonwealth-in-action/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNESCO. Data for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- UNEP. Progress in the implementation of the programme of action for the sustainable development of small island developing States. Report of the Secretary-General–Addendum. In Proceedings of the Commission on Sustainable Development, Sixth Session, New York, NY, USA, 20 April–1 May 1998; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, A.; Freebody, P.; Shun, L.; Gopinathan, S. Towards research-based innovation and reform: Singapore schooling in transition. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2005, 25, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, K. Global assemblage: Singapore, foreign universities, and the construction of a “global education hub”. World Dev. 2007, 35, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, M.; Holmes, K. Challenges for educational research: International development, partnerships and capacity building in small states. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2001, 27, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBIT. The Capacity Building Initiative for Transparency (CBIT) Global Coordination Platform. Available online: https://www.cbitplatform.org/about (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Gattuso, J.-P.; Magnan, A.; Billé, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Howes, E.L.; Joos, F.; Allemand, D.; Bopp, L.; Cooley, S.R.; Eakin, C.M.; et al. Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science 2015, 349, aac4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betti, M. ASLO 2009: The Marine Environment Laboratories of the International Atomic Agency, Monaco (IAEA-MEL). Limnol. Oceanogr. Bull. 2008, 17, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).