Abattoir Survey of Dairy and Beef Cattle and Buffalo Haemonchosis in Greece and Associated Risk Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

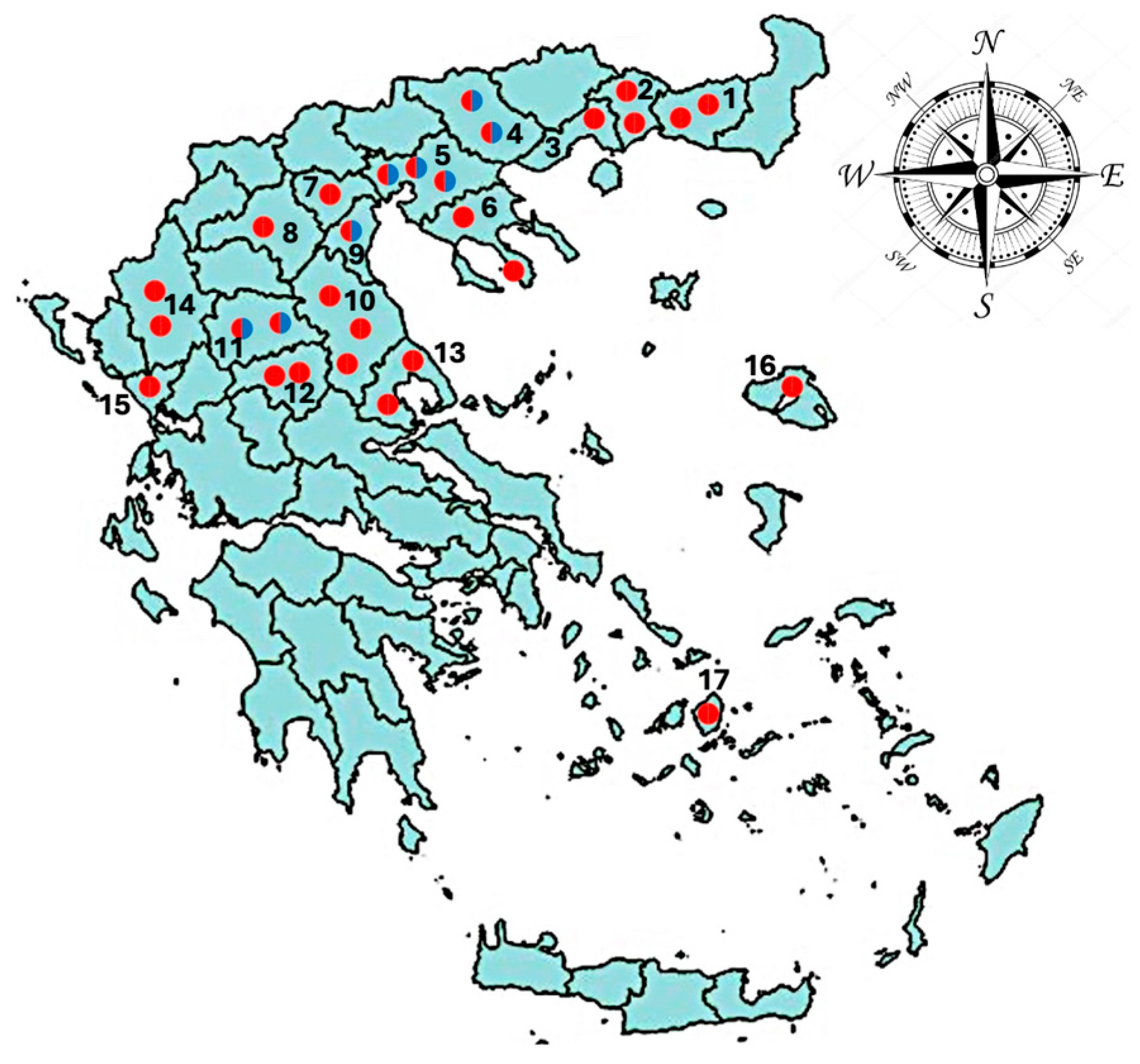

2.1. Study Design—Methodology

2.2. Collection and Post-Mortem Examination of Abomasa

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Molecular Identification of H. contortus

2.5. Estimation of Pro/Benzimidazole Resistance/Susceptibility Status of Haemonchus contortus

2.6. Data Handling—Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Identification of Haemonchus spp.

3.2. Prevalence of H. contortus Infection

3.3. Descriptive Results

3.4. Risk Factors of Cattle and Buffaloes Infected by H. contortus

3.5. Risks Factors of H. contortus Isolated from Cattle and Buffaloes Carrying β-Tubulin Isotype 1 Gene with Homozygous Alleles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Familton, A.S.; McAnulty, R.W. Life cycles and development of nematode parasites of ruminants. In Sustainable Control of Internal Parasites in Ruminants; Barrell, G.K., Ed.; Lincoln University: Canterbury, New Zealand, 1997; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B.D.; Randolph, T.F. Improving the assessment of the economic impact of parasitic diseases and of their control in production animals. Vet. Parasitol. 1999, 84, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, F.; Jackson, F. Targeted flock/herd and individual ruminant treatment approaches. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 186, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurden, T.; Chartier, C.; Fanke, J.; Frangipane di Regalbono, A.; Traversa, D.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.; Demeler, J.; Vanimisetti, H.B.; Bartram, D.J.; Denwood, M.J. Anthelmintic resistance to ivermectin and moxidectin in gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle in Europe. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2015, 5, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.A.; Coop, R.L.; Wall, R.L. Veterinary Parasitology, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil, B.; Nunes, R.; Bastianetto, E.; Drummond, M.; Carvalho, D.; Leite, R.C.; Molento, M.; Oliveira, D. Genetic diversity patterns of Haemonchus placei and Haemonchus contortus populations isolated from domestic ruminants in Brazil. Int. J. Parasitol. 2012, 42, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T. Gastrointestinal Nematodes Infecting Water Buffalo: A Comparison Between Australia and Pakistan Assessing Species Identification, Prevalence and Farming Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Charles Sturt University, New South Wales, Australia, March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.K.; Sharma, R.K. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in Indian buffaloes. Vet. Parasitol. 1986, 20, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, I.A.; Scott, I. Gastrointestinal Nematodes of Sheep and Cattle: Biology and Control, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Katsarou, E.I.; Mendoza Roldan, J.A.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Papadopoulos, E. Haemonchus contortus parasitism in intensively managed cross-limousin beef calves: Effects on feed conversion and carcass characteristics and potential associations with climatic conditions. Pathogens 2022, 11, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjigeorgiou, I.; Osoro, K.; Fragoso de Almeida, J.P.; Molle, G. Southern European grazing lands: Production, environmental and landscape management aspects. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 96, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygoyiannis, D. Sheep Husbandry, 1st ed.; Contemporary Education: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, E.; Gallidis, E.; Ptochos, S. Anthelmintic resistance in sheep in Europe: A selected review. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 164, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicarelli, L. Buffalo milk: Its properties, dairy yield and mozzarella production. Vet. Res. Commun. 2004, 1, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infascelli, F.; Gigli, S.; Campanile, G. Buffalo meat production: Performance infra vitam and quality of meat. Vet. Res. Commun. 2004, 1, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somparn, P.; Gibb, M.J.; Markvichitr, K.; Chaiyabutr, N.; Thummabood, S.; Vajrabukka, C. Analysis of climatic risk for cattle and buffalo production in northeast Thailand. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2004, 49, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghese, A. Situation and perspectives of buffalo in the world, Europe and Macedonia. Maced. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 1, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founta, A.; Papazachariadou, M.; Papadopoulos, E.; Chliounakis, S.; Antoniadou-Sotiriadou, K.; Karamitros, A.; Efremidis, K. Fauna of gastrointestinal parasites of buffaloes in the area of Macedonia, Greece. Anim. Sci. Rev. 2007, 36, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, E.; De Palo, P.; Tidona, F.; Maggiolino, A.; Bragaglio, A. Dairy buffalo life cycle assessment (LCA) affected by a management choice: The production of wheat crop. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrusfield, M.V. Veterinary Epidemiology, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, H.C. Mechanisms of survival of nematode parasites with emphasis on hypobiosis. Vet. Parasitol. 1982, 11, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulos, G.; Peristeropoulou, P.; Kouam, M.K.; Kantzoura, V.; Theodoropoulou, H. Survey of gastrointestinal parasitic infections of beef cattle in regions under Mediterranean weather in Greece. Parasitol. Int. 2010, 59, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Minoudi, S.; Symeonidou, I.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Papadopoulos, E. Extensive countrywide molecular identification and high genetic diversity of Haemonchus spp. in domestic ruminants in Greece. Pathogens 2024, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, D.; Mable, B.K.; Larson, A.; Davis, S.K.; Zimmer, E.A. Nucleic acids IV: Sequencing and cloning. In Molecular Systematics, 2nd ed.; Hills, D., Moritz, C., Mable, B.K., Eds.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 321–382. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, J.H.; Elard, L. A simple PCR method for rapidly detecting defined point mutations. Tech Tips Online 1997, 2, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Desboulets, L.D.D. A review on variable selection in regression analysis. Econometrics 2018, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Papadopoulos, E. Abattoir countrywide survey of dairy small ruminants’ haemonchosis in Greece and associated risk factors. Animals 2025, 15, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besier, R.B.; Kahn, L.P.; Sargison, N.D.; VanWyk, J.A. The pathophysiology, ecology and epidemiology of Haemonchus contortus infection in small ruminants. Adv. Parasitol. 2016, 93, 95–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barger, I.A. The role of epidemiological knowledge and grazing management for helminth control in small ruminants. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Minoudi, S.; Symeonidou, I.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Katsafadou, A.I.; Lianou, D.T.; Fthenakis, G.C.; Papadopoulos, E. Frequency of resistance to benzimidazoles of Haemonchus contortus helminths from dairy sheep, goats, cattle and buffaloes in Greece. Pathogens 2020, 9, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijk, J.; Sargison, N.D.; Kenyon, F.; Skuce, P.J. Climate change and infectious disease: Helminthological challenges to farmed ruminants in temperate regions. Animal 2010, 4, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polley, L.; Hoberg, E.; Kutz, S. Climate change, parasites and shifting boundaries. Acta Vet. Scand. 2010, 52, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Rashid, I.; Shabbir, M.Z.; Aziz-Ul-Rahman Shahzad, K.; Ashraf, K.; Sargison, N.D.; Chaudhry, U. Emergence and the spread of the F200Y benzimidazole resistance mutation in Haemonchus contortus and Haemonchus placei from buffalo and cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 265, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, U.; Redman, E.M.; Ashraf, K.; Shabbir, M.Z.; Rashid, M.I.; Ashraf, S.; Gilleard, J.S. Microsatellite marker analysis of Haemonchus contortus populations from Pakistan suggests that frequent benzimidazole drug treatment does not result in a reduction of overall genetic diversity. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, H.; Jebali, J.; Gharbi, M.; Mhadhbi, M.; Awadi, S.; Darghouth, M.A. Epidemiological study of sympatric Haemonchus species and genetic characterization of Haemonchus contortus in domestic ruminants in Tunisia. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 193, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisimwa, N.P.; Lugano, R.M.; Bwihangane, B.A.; Wasso, S.D.; Kinimi, E.; Banswe, G.; Bajope, B. Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminths in slaughtered cattle in Walungu territory, South Kivu Province, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Austin J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 2018, 5, 1039. [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan, H.M.; Zohaib, H.M.; Sajid, M.S.; Tahir, U.B.; Kausar, R.; Nazish, N.; Ben Said, M.; Anwar, N.; Maqbool, M.; Fouad, D.; et al. Unveiling the hidden threat: Investigating gastrointestinal parasites and their costly impact on slaughtered livestock. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2024, 33, e007224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.C.; Silva, B.F.; Amarante, A.F.T. Environmental factors influencing the transmission of Haemonchus contortus. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 188, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Pizaña, A.; Alberto de la Cruz-Cruz, L.; Tarazona-Morales, A.; Roldan-Santiago, P.; Ballesteros-Rodea, G.; Pineda-Reyes, R.; Orozco-Gregorio, H. Physiological and behavioral changes of water buffalo in hot and cold systems: Review. J. Buffalo Sci. 2020, 9, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katwal, S.; Choudhary, S.; Sandhu, K.; Singh, Y. Wallowing in buffaloes: An overview of its impact on behaviour, performance, health and welfare. Indian J. Anim. Prod. Manag. 2024, 40, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Papanikolopoulou, V.; Dokou, S.; Tsitsos, A.; Priskas, S.; Vouraki, S.; Argyriadou, A.; Arsenos, G. Economic performance and meat quality traits of extensively reared beef cattle in Greece. Animals 2025, 15, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistopanidis, G.I. Economics of extensive beef cattle farming in Greece. New Medit 2004, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare. The Welfare of Cattle Kept for Beef Production, 1st ed.; European Commission Health and Consumer Protection Directorate-General: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol-van Dasselaar, A.; Hennessy, D.; Isselstein, J. Grazing of dairy cows in Europe—An in-depth analysis based on the perception of grassland experts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafakas, S.; Tsiplakou, E.; Kotsarinis, M.; Tsiboukas, K.; Zervas, G. Identification of efficient dairy farms in Greece based on home grown feedstuffs, using the Data Envelopment Analysis method. Livest. Sci. 2019, 222, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaundry, U.; Miller, M.; Yazwinski, T.; Kaplan, R.; Gilleard, J. The presence of benzimidazole resistance mutations in Haemonchus placei from US cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 204, 411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kotze, A.C.; Prichard, R.K. Anthelmintic resistance in Haemonchus contortus: History, mechanisms and diagnosis. Adv. Parasitol. 2016, 93, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lima, W.S. Seasonal infection pattern of gastrointestinal nematodes of beef cattle in Minas Gerais State-Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 1998, 74, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honer, M.R.; Bianchin, I.; Nascimento, Y.A. The interpretation of the population dynamics of bovine gastrointestinal nematodes with the use of tracer animals. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet 1992, 1, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Flay, K.J.; Hill, F.I.; Muguiro, D.H. A Review: Haemonchus contortus Infection in pasture-based sheep production systems, with a focus on the pathogenesis of anaemia and changes in haematological parameters. Animals 2022, 12, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, P.K. Pharmacokinetic behavior of fenbendazole in buffalo and cattle. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, P.K. Kinetic disposition of triclabendazole in buffalo compared to cattle. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995, 8, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlier, J.; van der Voort, M.; Kenyon, F.; Skuce, P.; Vercruysse, J. Chasing helminths and their economic impact on farmed ruminants. Trends Parasitol. 2014, 30, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanyari, M.; Suryawanshi, K.R.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Dickinson, E.; Khara, A.; Rana, R.S.; Vineer, H.R.; Morgan, E.R. Predicting parasite dynamics in mixed-use trans-Himalayan pastures to underpin management of cross-transmission between Livestock and Bharal. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 714241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumelle, C.; Toïgo, C.; Papet, R.; Benabed, S.; Beurier, M.; Bordes, L.; Brignone, A.; Curt-Grand-Gaudin, N.; Garel, M.; Ginot, J.; et al. Cross-transmission of resistant gastrointestinal nematodes between wildlife and transhumant sheep. Peer Community J. 2024, 4, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoglund, J.; Gustafsson, K.; Ljungstrom, B.L.; Engstrom, A.; Donnan, A.; Skuce, P. Anthelmintic resistance in Swedish sheep flocks based on a comparison of the results from the faecal egg count reduction test and resistant allele frequencies of the betatubulin gene. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 161, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, A.C.; Cowling, K.; Bagnall, N.H.; Hines, B.M.; Ruffell, A.P.; Hunt, P.W.; Coleman, G.T. Relative level of thiabendazole resistance associated with the E198A and F200Y SNPs in larvae of a multi-drug resistant isolate of Haemonchus contortus. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2012, 2, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, E.; Whitelaw, F.; Tait, A.; Burgess, C.; Bartley, Y.; Skuce, P.J.; Jackson, F.; Gilleard, J.S. The emergence of resistance to the benzimidazole anthlemintics in parasitic nematodes of livestock is characterised by multiple independent hard and soft selective sweeps. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 6, e0003494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, M.; Kaminsky, R.; Maser, P. Phenotyping and genotyping of Haemonchus contortus isolates reveals a new putative candidate mutation for BZ resistance in nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2007, 144, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrère, V.; Álvarez, L.; Suárez, G.; Ceballos, L.; Moreno, L.; Lanusse, C.; Prichard, R.K. Relationship between increased albendazole systemic exposure and changes in single nucleotide polymorphisms on the β-tubulin isotype 1 encoding gene in Haemonchus contortus. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 186, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrère, V.; Falzon, L.C.; Shakya, K.P.; Menzies, P.I.; Peregrine, A.S.; Prichard, R.K. Assessment of benzimidazole resistance in Haemonchus contortus in sheep flocks in Ontario, Canada: Comparison of detection methods for drug resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 198, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrère, V.; Keller, K.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G.; Prichard, R.K. Efficiency of a genetic test to detect benzimidazole resistant Haemonchus contortus nematodes in sheep farms in Quebec. Can. Parasitol. Int. 2013, 62, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufener, L.; Kaminsky, R.; Maser, P. In vitro selection of Haemonchus contortus for benzimidazole resistance reveals a mutation at amino acid 198 of beta-tubulin. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009, 168, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.W.; Van Wyk, J.; Hamie, J.C.; Byaruhanga, C.; Kenyon, F. Refugia-based strategies for parasite control in livestock. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2020, 36, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, J.E.; Kaplan, R.M.; Kenyon, F.; Morgan, E.R.; Park, A.W.; Paterson, S.; Babayan, S.A.; Beesley, N.J.; Britton, C.; Chaudhry, U.; et al. Refugia and anthelmintic resistance: Concepts and challenges. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2019, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colditz, I.G.; Watson, D.L.; Gray, G.D.; Eady, S.J. Some relationships between age, immune responsiveness and resistance to parasites in ruminants. Int. J. Parasitol. 1996, 26, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocampos, G.M.; Riquelme, J.M. New record of parasitic protozoan and helminths in buffaloes from Paraguay. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2024, 11, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartier, C.; Hoste, H. Response to challenge infection with Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in dairy goats: Differences between high- and low-producers. Vet. Parasitol. 1997, 73, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoste, H.; Chartier, C. Comparison of the effects on milk production of concurrent infection with Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in high- and low- producing dairy goats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1993, 54, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoste, H.; Chartier, C. Response to challenge infection with Haemonchus contortus and Trichostronylus colubriformis in dairy goats: Consequences on milk production. Vet. Parasitol. 1998, 74, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arundel, J.H.; Hamilton, D. The effect of mixed grazing of sheep and cattle on worm burdens in lambs. Aust. Vet. J. 1975, 51, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1. Abattoir’s Information |

| Location of the abattoir |

| Visit day |

| Season |

| Spring |

| Summer |

| Autumn |

| Winter |

| 2. Animal’s Information |

| Age |

| Months |

| Sex |

| Male |

| Female |

| Species |

| Cattle |

| Buffalo |

| Productive orientation |

| Milk |

| Meat |

| 3. Farm’s Information |

| Management system |

| Grazing |

| Zero-grazing |

| Altitude |

| ≤300 m a.s.l. |

| >300 m a.s.l. |

| Co-existence of cattle and buffaloes |

| Single-species farming |

| Mixed-species farming |

| Anthelmintic treatment |

| Exclusively pro/benzimidazoles |

| Exclusively macrocyclic lactones |

| Combination of pro/benzimidazoles |

| and macrocyclic lactones |

| No anthelmintic treatment |

| Primer | Sequence | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| NC1-F | forward: 5′-ACGTCTGGTTCAGGGTTGTT-3′ | 321 |

| NC2-R | reverse: 5′-TTAGTTTCTTTTCCTCCGCT-3′ |

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| P1 | Fw: 5′-GTCCCACGTGCTGTTCTTG -3′ |

| P2S | Rv: 5′-TACAGAGCTTCATTAATCGATGCAGA -3′ |

| P3R | Fw: 5′-TTGGTAGAAAACACCGATGAAACATA -3′ |

| P4 | Rv: 5′-GATCAGCATTCAGCTGTCCA -3′ |

| Population | Prevalence (%) | Hc-Infected abom./Total abom. |

|---|---|---|

| Large ruminants | 31.0 | 66/213 |

| Cattle | 21.2 | 36/170 |

| Buffaloes | 69.8 | 30/43 |

| Dairy cattle | 10.4 | 12/115 |

| Beef cattle | 43.6 | 24/55 |

| Ruminants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy Cattle * | % | Beef Cattle * | % | Buffaloes * | % | |

| Co-existence of cattle and buffaloes | ||||||

| Single-species farming | 11 | 91.67 | 13 | 54.17 | 22 | 73.33 |

| Mixed-species farming | 1 | 8.33 | 11 | 45.83 | 8 | 26.67 |

| Anthelmintic treatment | ||||||

| Pro/benzimidazoles | 0 | 0.00 | 10 | 41.67 | 6 | 20.00 |

| Macrocyclic lactones | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 12.50 | 6 | 20.00 |

| Pro/benzimidazoles and Macrocyclic lactones | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| No anthelmintic treatment | 12 | 100.00 | 11 | 45.83 | 18 | 60.00 |

| Altitude | ||||||

| ≤300 m a.s.l. | 10 | 83.33 | 17 | 70.83 | 30 | 100.00 |

| >300 m a.s.l. | 2 | 16.67 | 7 | 29.17 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Management system | ||||||

| Semi-intensive | 6 | 50.00 | 18 | 75.00 | 30 | 100.00 |

| Intensive | 6 | 50.00 | 6 | 25.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 6 | 50.00 | 19 | 79.17 | 20 | 66.67 |

| Female | 6 | 50.00 | 5 | 20.83 | 10 | 33.33 |

| Season | ||||||

| Spring | 6 | 50.00 | 4 | 16.67 | 8 | 26.67 |

| Summer | 5 | 41.67 | 3 | 12.50 | 8 | 26.67 |

| Autumn | 0 | 0.00 | 13 | 54.17 | 13 | 43.33 |

| Winter | 1 | 8.33 | 4 | 16.67 | 1 | 3.33 |

| Risk Factors | B | S.E. | Wald | p-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. for Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Mixed-species farming | 0.89 | 0.521 | 2.96 | 0.055 | 2.45 | 0.98 | 6.81 |

| Single-species farming | Ref. | ||||||

| Beef cattle | 2.39 | 0.507 | 22.320 | 0.000 | 10.95 | 4.06 | 29.54 |

| Dairy cattle | Ref. | ||||||

| Animal age (months) | 0.03 | 0.006 | 18.76 | 0.000 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.04 |

| Grazing | 0.74 | 0.506 | 2.15 | 0.142 | 2.10 | 0.78 | 5.67 |

| Zero-grazing | Ref. | ||||||

| Male | −0.59 | 0.539 | 1.21 | 0.271 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 1.40 |

| Female | Ref. | ||||||

| Constant | −3.53 | 0.515 | 46.87 | 0.000 | 0.03 | ||

| Ruminant | Risk Factor | B | S.E. | β-Coefficient | t | p-Value | 95% C.I. for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Cattle 25.0% RR or 720/2880 | Intensive | 1.853 | 0.458 | 0.393 | 4.047 | 0.000 | 0.938 | 2.768 |

| Semi-intensive | Ref. | |||||||

| Slaughter age (months) | 0.023 | 0.005 | 0.474 | 4.888 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.033 | |

| Female | −0.315 | 0.404 | −0.081 | −0.779 | 0.439 | −1.123 | 0.493 | |

| Male | Ref. | |||||||

| Mixed-species farming | −0.283 | 0.399 | −0.071 | −0.709 | 0.481 | −1.080 | 0.515 | |

| Single-species farming | Ref. | |||||||

| Constant | 0.571 | 0.254 | 2.245 | 0.028 | 0.063 | 1.079 | ||

| Βuffaloes 8.3% RR or 199/2400 | Slaughter age (months) | −0.248 | 0.128 | −0.320 | −1.933 | 0.054 | −0.512 | 0.015 |

| Mixed-species farming | −0.825 | 0.362 | −0.376 | −2.278 | 0.031 | −1.568 | −0.082 | |

| Single-species farming | Ref. | |||||||

| Female | −0.418 | 0.346 | −0.203 | −1.208 | 0.238 | −1.129 | 0.293 | |

| Male | Ref. | |||||||

| Constant | 6.597 | 2.854 | 2.311 | 0.029 | 0.740 | 12.454 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arsenopoulos, K.V.; Gelasakis, A.I.; Papadopoulos, E. Abattoir Survey of Dairy and Beef Cattle and Buffalo Haemonchosis in Greece and Associated Risk Factors. Dairy 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy7010003

Arsenopoulos KV, Gelasakis AI, Papadopoulos E. Abattoir Survey of Dairy and Beef Cattle and Buffalo Haemonchosis in Greece and Associated Risk Factors. Dairy. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleArsenopoulos, Konstantinos V., Athanasios I. Gelasakis, and Elias Papadopoulos. 2026. "Abattoir Survey of Dairy and Beef Cattle and Buffalo Haemonchosis in Greece and Associated Risk Factors" Dairy 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy7010003

APA StyleArsenopoulos, K. V., Gelasakis, A. I., & Papadopoulos, E. (2026). Abattoir Survey of Dairy and Beef Cattle and Buffalo Haemonchosis in Greece and Associated Risk Factors. Dairy, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/dairy7010003