Abstract

Examples of niche tourism have emerged in parallel to the growing importance of food tourism in destination management and marketing. Examples of this include mushroom tourism, tea tourism, or udon tourism, among others. This study analyzes one of this specialist forms of food tourism: dairy tourism. Dairy tourism is the leisure and tourist practice that leads to the discovery of production, transformation, and commercialization processes of milk and milk derivatives. Specifically, the objective of this research is to discuss the relationships between local dairy landscapes and tourism in the Catalan region of Empordà, in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula. Drawing on field visits and interviews with the seven regional producers, results describe the mechanisms of dairy tourism from a local marketing perspective.

1. Introduction

Examples of culinary tourism refer to the process of awarding tourism value to a specific local product [1,2,3], which becomes a leisure and tourist attraction. Previous research has focused on various types of niche food tourism involving products such as mushrooms [4] or cheese [5], and dishes such as paella [6] or noodles [7]. Also, other studies were based on beverages beyond the scope of wine tourism [8], such as beer tourism [9], coffee tourism [10], or tea tourism [11]. These tourism types have vast benefits for regional development [12,13,14], since tourist resources come from economic activities deeply rooted in the primary sector [15]. Examples of food tourism have a significant impact on both economic and social development of agricultural areas, and engage local growers with tourism development as a source of differentiation, distinction, and diversification [16,17,18]. In this context, one of the typologies that has been widely developed over the last few years is cheese tourism [19,20,21,22], where this relationship between territory, people, and sustainable tourism activity is manifested.

In particular, dairy tourism refers to the discovery of the processes associated with production, transformation, and marketing of milk and milk derivatives. However, previous research has not analyzed dairy tourism, which is the research gap this paper aims to fill in to expand the understanding of the relationships between ‘dairy’ and ‘tourism’. The objective of this research is, first, to define the term ‘dairy tourism’. As mentioned above, dairy tourism, like other examples of special interest food tourism, elevates a natural resource to a tourism dimension [23]. Dairy tourism constructs bridges between territory and tourism through dairy products. This research understands ‘dairy’ as a relevant foodscape, and as part of the food tourism system of a destination. Dairy products are identity food products that communicate the cultural and natural idiosyncrasies of a territory to visitors. The development of this typology starts from the understanding of dairy industry as an example of food practice and culinary landscape.

The conceptualization of a landscape considers more than its tangible aspects—a place is seen, heard, smelled, tasted, and touched [24], but its intangible aspects also generate and stimulate emotions and memories [25,26]. In the context of tourism, a range of scape-based forms emerged. Among them, ‘foodscapes’ are defined as “cultural, economic, historical, personal, political, or social landscapes that, in one way or another, are about food” [27]. In this context, ‘place’ plays a significant role as a geographic location but ‘place’ is also a combination of “destination qualities, including landscape and architecture, history and heritage and social structures and relationships” [28]. Food is a pivotal component of sense of place, and one of the avenues through which the uniqueness of a destination is communicated—its terroir [29]. Terroir acknowledges the relationship between a land and its people [30]. In this context, the relationships between primary production, food, and culture are the foundation of food offerings which, as a sum, narrate the foodscapes of a region [31]. At the same time, food heritages and culinary practices are a pathway for cultural communication [32] and serve to convey the values attached to ‘food’ in a defined environment. Food activities include a range of aspects such as the dynamics of production, distribution, sale or consumption [33] which inform the construction of a ‘foodscape’. This paper analyzes dairyscapes as examples of local landscapes, and it focuses on the perspectives of food producers, which are part of the food system of a destination.

Notably, the production of milk and milk derivatives is thousands of years old. Each region has its own production which transmits its authenticity and identity, with its own characteristics that differentiate milk products that cannot be recreated anywhere else—a milk derivative is made of milk which is obtained from animals grazing in a specific portion of land and relies on a place’s unique features. For example, a cheese made with cow’s milk from the Catalan Pyrenees is different than a cheese made with cow’s milk from the Switzerland Alps. Even a cheese made in summer is different than a cheese made in winter because weather changes animals’ diet. This is later transferred to milk and cheese, which also encapsulates the seasonal flavors [34]. Although the artisanal production of milk products is a symbol of regional distinction in Catalonia in general and in Empordà in particular, the industrialization of agricultural and farming activities led to the interruption of many of these productions [35], which were mostly limited to a familiar environment. However, during the last half of the 20th century, the revalorization of traditional activities and the promotion of slow practices resulted in the resurgence of various types of artisanal food processing [36], such as cheese making [37]. Furthermore, the motivation of visitors towards the handmade production of dairy products is not only related to food tourism itself, but it also includes attraction factors linked to other types of tourism such as cultural tourism (production techniques) [38], natural tourism (environment where animals live), [39] or in a broader sense, rural tourism [40] and urban tourism [41] depending on whether you visit a city or a periphery and the food motivation [42].

2. Methods

This paper aims to study the relationships between milk products and tourism from a marketing perspective in the region of Empordà, which includes Alt and Baix Empordà areas, in the province of Girona (Catalonia, Spain). In order to identify all the dairy producers in Empordà, several actions were carried out. First, two visits were made to the markets of Girona. Specifically, Mercat del Lleó and the weekly market were visited in March and June, 2018. In addition, conversations were performed with tourism management and promotion institutions in the region of Girona, including Patronat de Turisme Costa Brava Girona and the Alt and Baix Empordà tourism offices. As a result of this initial fieldwork, a total of seven producers of milk and milk derivatives, such as cheese, were identified. Four are located in Alt Empordà and three are located in Baix Empordà (Table 1), and all of them participated in this research.

Table 1.

List of dairy producers in Empordà, Girona (Catalonia, Spain).

The qualitative study method is based on interviews and personal visits to the production and processing facilities. Interviews are used in qualitative research [43,44] in order to understand a particular topic [45] and construct a narrative [46]. The combination of interviews and visits to the fields is used to capture the significance of local products [47,48], which is especially relevant for local production dialogues with tourism [49,50]. This research explains the relationships between ‘dairy’ and ‘tourism’. In particular, seven visits were made in August 2018 to the seven regional producers, located in the towns of Cabanelles, Palau-Saverdera, Siurana d’Empordà, and Vilanova de la Muga (Alt Empordà), and Fonteta, Jafre, and Ullastret (Baix Empordà). The visits and interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min. Based on the interactions between dairy and tourism, results of this research identify the dimensions of dairy tourism.

3. Results: The Relationships between Dairy and Tourism

Both the dairy and tourism industries play a pivotal role in European economies. As reported by the European Commission, milk production represents a significant value of European Union agriculture with an aggregate production of more than 150 million tonnes every year, with Spain as one of the main producers [51,52]. With regards to tourism, European destinations account for half of international arrivals, and Spain is the second most visited country in the world [53,54]. Also, both dairy and tourism are working towards the development of initiatives to face climate change and global warming and developing a sustainable future through sustainable food systems [55], which is confirmed by the emergence of recent trends such as slow tourism [56,57,58,59,60,61].

As a result of the visits to the facilities, and the conversations with the producers, this section describes the relationships between the elaboration of dairy products and tourism in Empordà. Due to the great reduction in the economic importance of the primary sector in recent decades in Catalan and Spanish rural areas [62,63,64], farmers and growers were urged to diversify their production in order to maintain the viability of their activity, thus engaging with tourism [65]. In this context, the region of Empordà, in the northeast of Catalonia, is one of the main areas of the Iberian Peninsula for primary industries, and the production of milk and milk derivatives, mainly fresh types [66]. Its climatic and orographic conditions—it is located between the Pyrenees and the Costa Brava natural landscapes, and culture make it a place that generates a unique dairy product [67]. Previous publications showcase that recuits (a type of local fresh cheese) are the most emblematic food product of Empordà [35]. Recuits became very popular during the last century both at home and restaurants, which adopted this dairy product as an identity dessert [36].

Empirical work carried out in this study shows the relationships that are established between producers and tourism which, from the perspective of local marketing, include the following aspects.

3.1. Direct Selling and On-Site Visits

Dairy products can either be eaten on the spot or they can be carried in a suitcase as a souvenir to remember the taste of Empordà later or to let other people try it through its milk and milk derivatives. Food tourism “is the act of traveling for a taste of place in order to get a sense of place” [68]. In this context, in relation to the process of making dairy products (Figure 1a,b), there are a number of opportunities to organize tastings (Figure 2a) and market non-food souvenirs such as handmade soaps, or bracelets made of sheep’s wool, which was observed for example in the shop of Mas Marcè (Figure 2b). This is part of the creative processes that diversify the range of products offered beyond food, and fits with the notion of creative tourism [69,70,71] that nowadays also defines the food tourism experience [72,73,74].

Figure 1.

(a) Example of cheese making process and (b) example of milk bottling.

Figure 2.

(a) A cheese tasting and (b) clothes made of sheep’s wool.

Similarly, a visit to the farms and workshops, which is the space where primary activities take place, provide a direct source of authenticity where visitors can obtain a direct contact with producers and the environment [3]. Natural landscapes are places where agriculture and farming, rural economic development, and tourism are merged. Therefore, visitable producers deliver a very important added-value to their food production where they can explain a contextualized narrative [34] and engage visitors with the story of food production and consumption focused on the historical and contemporary values attached to ‘dairy’. Currently, however, only ‘Mas Marcè-Ecolàctics Peralada’ is listed as a visitable producer in the catalog of food and wine experiences of the Patronat de Turisme Costa Brava Girona. In addition, other producers such as ‘Recuits i formatges Nuri’ organize visits through tourism associations such as Visit Empordanet, which promotes experiences of producers that are complemented by tastings of Empordà cuisine.

3.2. The Menus of Restaurants

Restaurant and dining experiences are the primary distribution channel for dairy producers. Many of them started to develop a relationship with tourism thanks to the demand for milk and milk derivatives by both inns and restaurants, which largely incorporate local products into their menus. For example, fresh cheeses (recuit) and cheesecakes are included in many restaurant menus which advocate for a cuisine that communicates the taste of the region. As described above, to taste a ‘recuit’ is to symbolically taste Empordà. In addition to dine-in options, the current situation derived from the impact of Covid-19 has also urged restaurants to change food supply management [75] and offer delivery and take-away services [76], which also include desserts (Figure 3a). ‘La Fonteta’ is the producer that has more widely consolidated its presence on the menus of regional restaurants. The region of Empordà shows that although tourism demand is very seasonal and concentrated on weekends and holiday periods [77], it is also sometimes repetitive and dependent on domestic tourism [78], which increases both producers’ and restaurants’ revenue.

Figure 3.

(a) Takeaway desserts and (b) a farmers’ market in the city of Girona.

3.3. Local Fairs and Markets

Both locals and visitors taste the territory more closely if the sale is made directly at the source. This interaction between producers and consumers can be done in the production area, as seen above, or through local agri-food shops and markets, which are regarded as significant tourism attractions [79,80,81]. Previous research highlighted food events as spaces where food heritage is protected and promoted [82]. In particular, food events in rural areas are drivers for tourism development [83], as occurs with food festivals in Empordà—for example, there is a cheese event in Lladó, Alt Empordà, which in 2021 will organize its twenty-fifth edition.

Although supermarkets have changed the habits of consumption—and of tourists—there is still a demand for local produce based on its authenticity and its production location. Fairs and culinary exhibitions are hallmarks of food and cultural landscapes of Catalonia, and in particular of Girona [84]. In this sense, farmers’ markets (Figure 3b) have a great acceptance both from local producers and visitors, and represent another form of marketing and distribution [85,86]. These fairs have a growing number of producers, especially cheesemakers, who thus respond to a growing demand for this product.

3.4. Also in Supermarkets

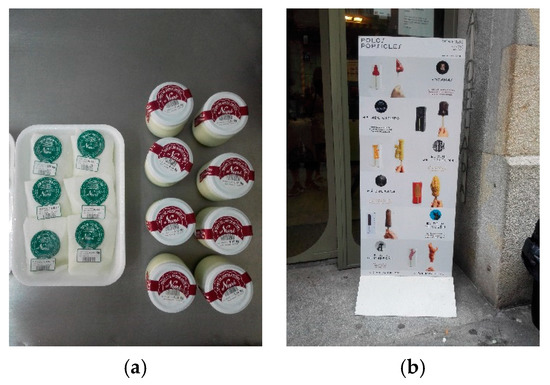

In addition to the direct consumption, it is observed that there is an increasing presence of Empordà dairy products in supermarkets (Figure 4a), which is observed mainly with yogurts but also with fresh products such as cheese. Most of the producers studied are represented in supermarkets. The visibility of supermarkets represents an avenue to the economic subsistence of producers, and also to improve their brands. This is also relevant under a tourism context (see [87]), as apartments and campsites are especially significant accommodation options in destinations such as Costa Brava [88] and both require—as part of their customers’ tourist consumption—the purchase of local products in supermarkets.

Figure 4.

(a) Dairy products (artisanal recuit and yogurt) and (b) ice-cream shop.

3.5. The Benefits of Combining Local Products

The associations of dairy products, such as cheeses, with other food, beverage and services—for example, hotels and campsites—encourage the consumption of local products, but also the projection of Empordà dairy producers as gatekeepers of the territory and the sense of place. This includes, for example, collaboration between dairy producers and ice cream factories (Figure 4b). The joint work with celebrity restaurants in Empordà counties is also an example of cooperation. In this context, celebrity chefs have spread food heritages and culinary landscapes to people [89]. They have developed gastronomy landmarks and visitor attractions [90] with huge implications for destination management and marketing [91]. Both cooks and restaurants are a media platform to communicate the territory through ‘dairy’ to an audience who appreciates the taste of Empordà food as a taste of Empordà terroir.

3.6. The Virtual Experience

Nowadays, technologies and social media play a significant role as part of the management and marketing strategies of local businesses [92], as well as with regards to food businesses [93]. However, the results show the online promotion of local producers is limited to a website and a minor presence on social media. This must be expanded in order to complement the initiatives that are organized by tourism management and promotion institutions in the region, such as Cuina de l’Empordanet [94]. Only a few participants such as ‘Recuits i formatges Nuri’ offered a visitor experience listed on websites like Airbnb. This is the way forward for local producers, which are family and small businesses with limited economic resources, as was observed in other studies [1].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Dairy tourism is a niche tourism focused on the interest of visitors towards all the resources associated with the production and consumption of milk products. Drawing on the visits and interviews carried out with producers in the region of Empordà in the northeastern area of Catalonia, the main contribution of the article is the definition of the relationships between primary activities and tourism through the case of milk products and milk derivatives. Research has confirmed that these relationships are currently built from various perspectives. The overall dairy tourism experience includes practices that allow people to discover the cultural and natural context of milk. This is manifested in visits to the workshops and the landscapes where animals graze, and also through direct consumption of products in different spaces, beyond restaurants, such as fairs and markets as forms of direct distribution, and supermarkets as an example of indirect distribution.

Dairy tourism as a type of food tourism emerges from the initiatives developed by regional entrepreneurs, who establish a sustainable relationship between food and tourism. In this context, bridges between dairy and tourism industry from a local marketing perspective were discussed. Foodscapes create a sense of place [95] which is communicated by the producers. When visitors engage in a host-guest relationship they ‘consume’ the landscape [96], which is also part of the storytelling of a destination [97] and its brand [98]. Food tourism can also contribute to the preservation and promotion of rural attractions and lifestyles [99,100,101]. As previous research did, this paper analyzes “how foodscapes potentially provide a foundation from which visitors can have a more meaningful and authentic experience by literally “tasting” the landscape” [102]. This was done in Empordà. Results have identified the local producers’ viewpoints of what a dairy tourism experience represents. This is subdivided into various dimensions, namely direct selling and visits, restaurants, local fairs and markets, supermarket chains, product combination, and online experiences. As an avenue towards the development of a competitive advantage focused on the culinary attributes of a destination [17], dairy tourism does not only narrate a connection between agriculture and tourism, but also a relationship between two major economic and social drivers of European nations, and between contributors towards the UNESCO sustainable development goals.

Girona in general and Empordà in particular are national and international gastronomy and tourism brands [103,104]. In this context, they underpin a close relationship between food and tourism through activities such as food and culinary trails [105,106]. In rural areas, cycling and hiking [107,108] tours may enhance the collaboration between food producers in order to spread a food attraction and develop the tourism dimension of local entrepreneurs. Cycling journeys focused on food are already offered throughout the world [109]. Local producers must interact with other providers and services in a territory. In the region of Empordà, Empordà Wine Route [110] is a paradigmatic example, which allows travelers to discover the landscapes of Costa Brava through its wines. As previously described, Empordà is a land of gastronomy [111], which combines products from the land and the sea, and where wine has a predominant presence [112]. Wine tastings also provide dairy producers with opportunities, and there are wineries that offer tastings where wine and cheese are paired. At the same time, fruit yogurts use locally grown fruits, for example apples, with the subsequent benefits for rural development. Dairy products agglutinate a wide variety of milk and milk derivatives, with products made from various animals’ milk, such as cows, goats, sheep, or even buffalos. Dairy tourism is the process of awarding tourism value to these products, their production, and their consumption.

This research has a number of implications, both theoretical and practical. At a theoretical level, it contributes to the development of literature on special examples of food tourism. In addition, it offers a perspective on tourism from the analysis of a local landscape focused on the dairy component of place. Local landscapes valued through tourism are a pathway to explore the cultural and natural heritages of a destination. In this case, the pathway involves the production and promotion of milk. In terms of practical implications, this research is useful for destination management and marketing to develop sustainable activities and experiences built directly by local producers. However, this article is limited to the perspective of producers. A definition of dairy tourism in a specific geographical context starts with landscapes and producers who work and love the land in everyday life practices. Also, this can include the study of consumer demand. Further research opportunities must apply the definition of dairy tourism to other geographies, the analysis of other types of culinary tourism, and the study of local and regional food landscapes from the opinions of other stakeholders and visitors. This would contribute to providing a stronger approach to dairyscapes and dairy tourism as an example of the sustainable relationships between territory and tourism.

Funding

This research was funded by ‘Càtedra de Gastronomia, Cultura i Turisme Calonge-St. Antoni’, University of Girona.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the availability of local producers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Mundet, L. A land of cheese: From food innovation to tourism development in rural Catalonia. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørstad, M.; Roaldsen, I.; Ljunggren, E. Local Food in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Gastron. Tour. 2020, 4, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, quality, and loyalty: Local food and sustainable tourism experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Seasonality in food tourism: Wild foods in peripheral areas. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Food Festivals and the Development of Sustainable Destinations. The Case of the Cheese Fair in Trujillo (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2922. [Google Scholar]

- Duhart, F.; Medina, F.X. Els espais socials de la paella: Antropologia d’un plat camaleònic. Revista d’Etnologia de Catalunya 2008, 32, 88–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Iwashita, C. Cooking identity and food tourism: The case of Japanese udon noodles. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, P.J. A review of global wine tourism research. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Telfer, D.; Hashimoto, A.; Summers, R. Beer tourism in Canada along the Waterloo–Wellington ale trail. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, L. (Ed.) Coffee Culture, Destinations and Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, L. (Ed.) Tea and Tourism: Tourists, Traditions and Transformations; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bertella, G. Re-thinking sustainability and food in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. (Eds.) Food Tourism and Regional Development: Networks, Products and Trajectories; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Star, M.; Rolfe, J.; Brown, J. From farm to fork: Is food tourism a sustainable form of economic development? Econ. Anal. Policy. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, T. Sustainability on a plate: Linking agriculture and food in the Fiji Islands tourism industry. In Tourism and Agriculture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Johansen, P.H. Food tourism in protected areas–sustainability for producers, the environment and tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knollenberg, W.; Duffy, L.N.; Kline, C.; Kim, G. Creating competitive advantage for food tourism destinations through food and beverage experiences. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Medina, J.A.; Medina, F.X. Traditional Mexican Cuisine: Heritage Implications for Food Tourism Promotion. J. Gastron. Tour. 2020, 4, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté Forné, F. Cheese tourism in a world heritage site: Vall de Boí (Catalan Pyrenees). Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 11, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Savouring place: Cheese as a food tourism destination landmark. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2020, 13, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaev, V.A.; Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. Cheese as a Tourism Resource in Russia: The First Report and Relevance to Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Developing cheese tourism: A local-based perspective from Valle de Roncal (Navarra, Spain). J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Slocum, S.L. Food and tourism: An effective partnership? A UK-based review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Berno, T. Food Tourism in New Zealand: Canterbury’s Foodscapes. J. Gastron. Tour. 2016, 2, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Destination foodscape: A stage for travelers’ food experience. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagence, M. ‘Scape’-based forms: A preliminary review of their use in the study of tourism-related activities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2014, 39, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adema, P. Festive Foodscapes: Iconizing Food and the Shaping of Identity and Place; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. A sense of place: Place, culture and tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, B.; Lee, S. Conceptualizing terroir wine tourism. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloire, A.; Prévost, P.; Kelly, M. Unravelling the terroir mystique: An agro-socio-economic perspective. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2008, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Barre, S.; Brouder, P. Consuming Stories: Placing food in the Arctic tourism experience. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, C.M.K.; de Ferrière le Vayer, M. Urban. Foodways and Communication: Ethnographic Studies in Intangible Cultural Food Heritages Around the World; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L.; Mitchell, R.; Macionis, N.; Cambourne, B. (Eds.) Food Tourism around the World; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Say Gouda, say cheese: Travel narratives of a food identity. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2004, 22, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arbós, S. La Cuina Empordanesa de les Mestresses de Peralada; Cossetània Edicions: Valls, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Associació Catalana de Ramaders Elaboradors de Formatges Artesans—ACREFA. Catàleg; ACREFA: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet-Coll, J. El Llibre del Recuit. Vida i Miracles d’un Llevant de Taula; Edicions Sidillà: Besalú, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, R.; Pozzi, A. Creating tourism experiences combining food and culture: An analysis among Italian producers. Tour. Review. 2018, 73, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čehić, A.; Mesić, Ž.; Oplanić, M. Requirements for development of olive tourism: The case of Croatia. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordili, S.; Tsakopoulou, K. Culinary tourism and rural development: Exploring the dynamic of “the Greek breakfast” initiative in Santorini. Επιθεώρηση Κοινωνικών Ερευνών 2019, 152, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, A.; Roy, H. Blending foodscapes and urban touristscapes: International tourism and city marketing in Indian cities. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, I. Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: Five cases. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, K.; DeMarrais, K.; Lewis, J.B. Learning to interview in the social sciences. Qual. Inq. 2003, 9, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, W.; Radel, K. (Eds.) Qualitative Methods in Tourism Research: Theory and Practice; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C. Qualitative research, tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism (s. 1–4); Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. Interviewing as a Form of Narrative Practice. In Qualitative Research; Silverman, D., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Tejada, O.; Gutiérrez Montoya, G.; Melchor Guevara, E.; Rodas, J.A. Aproximación al desarrollo económico local en el Municipio de Santa María Ostuma, Departamento de La Paz, El Salvador. Propuestas y acciones. Rev. Retos 2015, 10, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino Martínez, J.M. La producción de arroz del estado de Morelos: Una aproximación desde el enfoque SIAL. Estud. Soc. 2014, 22, 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Artieda-Ponce, M.P.; Macas-Mogrovejo, J.K.; Chango-Cañaveral, P.M.; Quezada-Sarmiento, P.A. Study on the Agricultural Products of the Towns Loja and Catamayo as a Historical Contribution on the Ecuadorian Gastronomy. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems; De Carvalho, J.V., Rocha, Á., Liberato, P., Peña, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, S. Production places or consumption spaces? The place-making agency of food tourism in Ireland and Scotland. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augère-Granier, M.L. The EU Dairy Sector; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Milk and Dairy Products. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/animals-and-animal-products/animal-products/milk-and-dairy-products (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- World Tourism Organization. European Union Tourism Trends; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Highlights; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Sustainable Dairy in Europe. Safeguarding Our Resources; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Inelmen, K. Effective management and governance of Slow Food’s Earth Markets as a driver of sustainable consumption and production. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payandeh, E.; Allahyari, M.S.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Surujlale, J. Good vs. Fair and Clean: An Analysis of Slow Food Principles Toward Gastronomy Tourism in Northern Iran. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.G.; de Sá, M.M.; Padilha, A.C.M.; de Souza, M. El movimiento slow food en el contexto del turismo enogastronómico: El caso de la Serra Gaúcha (RS, Brasil). Estud. Y Perspect. En Tur. 2020, 29, 369–389. [Google Scholar]

- Serdane, Z. Slow philosophy in tourism development in Latvia: The supply side perspective. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 17, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Qiao, G.; Chen, N. Tourist experience of slow tourism: From authenticity to place attachment–a mixed-method study based on the case of slow city in China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş Gürsoy, İ. Slow food justice and tourism: Tracing Karakılçık bread in seferihisar, Turkey. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, M. Rural tourism in Spain. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Priestley, G.K.; Blanco, A. Rural tourism in Spain: An analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum 2004, 35, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.M.G.; Martín, J.M.M.; Fernández, J.A.S.; Mogorrón-Guerrero, H. An analysis of the stability of rural tourism as a desired condition for sustainable tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.M.; Momsen, J.H. (Eds.) Tourism and Agriculture: New Geographies of Consumption, Production and Rural Restructuring; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Alimentación y turismo: Potencialidades de la elaboración de queso en España. Cult. Rev. De Cult. E Tur. 2018, 12, 60–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Formatges, Gastronomia i Turisme a l’Empordà; Càtedra de Gastronomia, Cultura i Turisme Calonge-St; Antoni, Universitat de Girona: Girona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Food Travel Association. What is Food Tourism? Available online: https://worldfoodtravel.org/what-is-food-tourism (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.K.; Kung, S.F.; Luh, D.B. A model of ‘creative experience’in creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Wei, L.; Zhang, T. Impact of tourist experience on memorability and authenticity: A study of creative tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, T.; Fountain, J. 'From the land': Identifying and communicating Selwyn's food story. In CAUTHE 2020: 20: 20 Vision: New Perspectives on the Diversity of Hospitality, Tourism and Events; Auckland University of Technology: Auckland, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.H.; Wall, G.; Kovacs, J.F. Creative food clusters and rural development through place branding: Culinary tourism initiatives in Stratford and Muskoka, Ontario, Canada. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, P.; Santa Cruz, F.G.; Gallo, L.S.P.; López-Guzmán, T. Gastronomic satisfaction of the tourist: Empirical study in the Creative City of Popayán, Colombia. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, S.; Aday, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F.; Hussain, A. We are open: Understanding crisis management of restaurants as pandemic hits tourism. J. Hosp. 2020, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Viajeros y pernoctaciones por zonas turísticas. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=2019 (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Rodríguez, M. El turisme català salva l’estiu de la Costa Brava. Available online: https://cat.elpais.com/cat/2020/08/13/catalunya/1597339233_645255.html (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Gilli, M.; Ferrari, S. Tourism in multi-ethnic districts: The case of Porta Palazzo market in Torino. Leis. Stud. 2018, 37, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkes, C.A. Farmers’ markets: A case for culinary tourism. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2012, 10, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. Farmers’ markets and tourism: Identifying tensions that arise from balancing dual roles as community events and tourist attractions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Paggiaro, A. Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Robinson, R.N. Foodies and food events. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 14, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulet, S.; Fernandez, J.M. Girona and its culinary events. In Managing and Developing Communities, Festivals and Events; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gendzheva, N. Model of Corporate Social Responsibility in food tourism. Int. J. Responsible Tour. 2014, 3, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J.; Stanley, L. Food Tourism: A Practical Marketing Guide; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Star chefs and the table: From restaurant to home-based culinary experiences. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 18, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDESCAT. Estadística de establecimientos turísticos. Available online: http://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=turall&lang=es (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Henderson, J.C. Celebrity chefs: Expanding empires. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giousmpasoglou, C.; Brown, L.; Cooper, J. The role of the celebrity chef. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, S.; Cifci, I. Delving into the Role of Celebrity Chefs and Gourmets in Culinary Destination Marketing. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 26, 2603. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovi, M.; Pucciarelli, F. Social media marketing in wine tourism: Winery owners’ perceptions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuina de l’Empordanet. Colectivo Gastronómico. Available online: http://www.cuinadelempordanet.com/es/#None (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Panelli, R.; Tipa, G. Beyond foodscapes: Considering geographies of indigenous well-being. Health Place 2009, 15, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, T.; Fusté-Forné, F. Imaginaries of cheese: Revisiting narratives of local produce in the contemporary world. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Warnaby, G.; Ashworth, G.J. (Eds.) Rethinking Place Branding: Comprehensive Brand Development for Cities and Regions; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bessière, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W.; Frost, J.; Strickland, P.; Maguire, J.S. Seeking a competitive advantage in wine tourism: Heritage and storytelling at the cellar-door. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, A.; Jamshidi, D. Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, H. Tea drinking and the tastescapes of wellbeing in tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque Meneguel, C.R.; Mundet, L.; Aulet, S. The role of a high-quality restaurant in stimulating the creation and development of gastronomy tourism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio-Vela, J.D.S.; Ginesta, X.; Kavaratzis, M. The critical role of stakeholder engagement in a place branding strategy: A case study of the Empordà brand. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.; Telfer, D.J. Culinary trails. In Heritage Cuisines; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Seyitoğlu, F. Tourist Experiences of Guided Culinary Tours: The Case of Istanbul. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Hall, C.M. Bicycle tourism and regional development: A New Zealand case study. Anatolia 1999, 10, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerton, S.; Sinclair, A.J. Buying local organic food: A pathway to transformative learning. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, M. 8 Food Tours around the World that are only available by Bike. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/biking-food-tours-around-the-world-2017-11 (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Patronat de Turisme Costa Brava Girona. Ruta del Vino DO Empordà. Available online: https://es.costabrava.org/que-hacer/enogastronomia/ruta-del-vino (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Pla, J. El Que Hem Menjat; Destino Ediciones: Barcelona, Spain, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Masramon, L. The Empordà. Wine region: The mediterranean paradise for wine tourism. Am. Wine Soc. J. 2017, 49, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).