A Single-Case Series Trial of Emotion-Regulation and Relationship Safety Intervention for Youth Affected by Sexual Exploitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. CSE Intervention

2.2. Emotion Regulation and CSE

2.3. The Current Study: ERIC + YR Intervention

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Setting

3.2. Participants

3.3. Materials

3.3.1. Emotion Regulation Impulse Control Program

3.3.2. Your Relationships

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Emotion Regulation Strategies Scale

3.4.2. The Outcome Rating Scale

3.4.3. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form

3.4.4. Relationship Safety Survey

3.4.5. Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire-Revised

3.4.6. Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory Short Form

3.5. Design

3.6. Procedure

3.7. Data Analysis

3.7.1. Statistical Significance

3.7.2. Clinical and Reliable Change

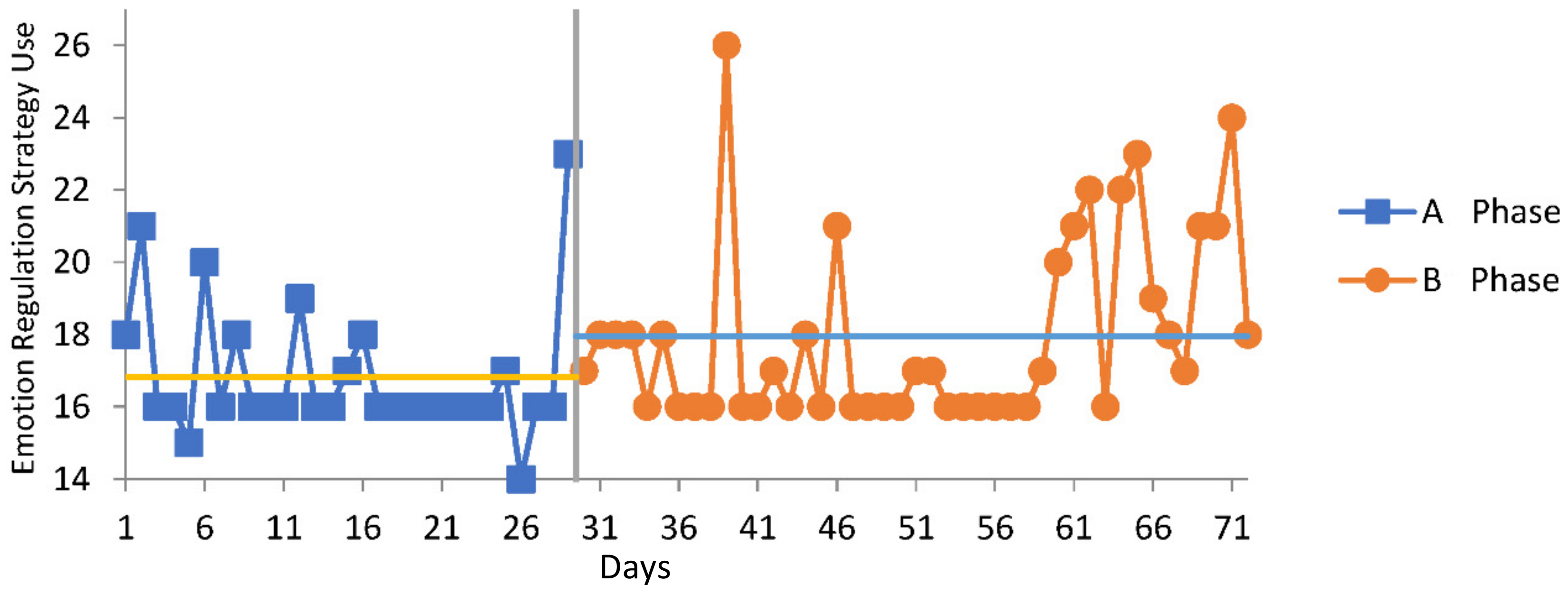

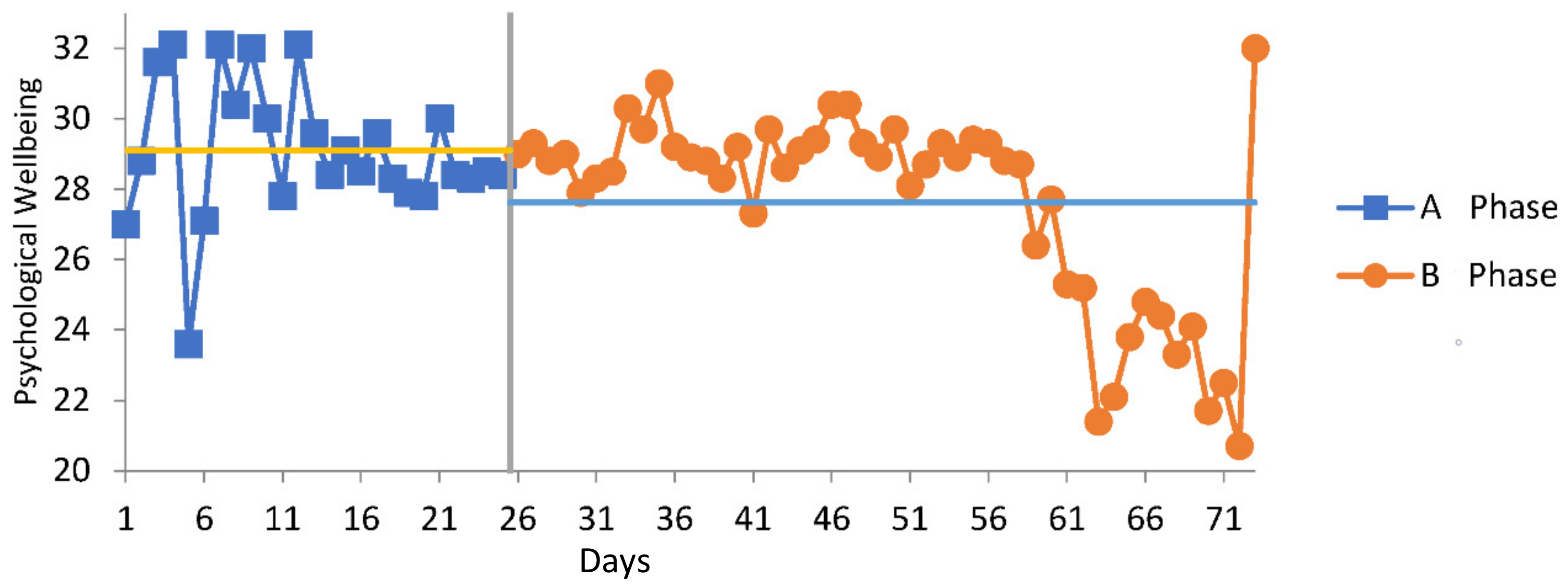

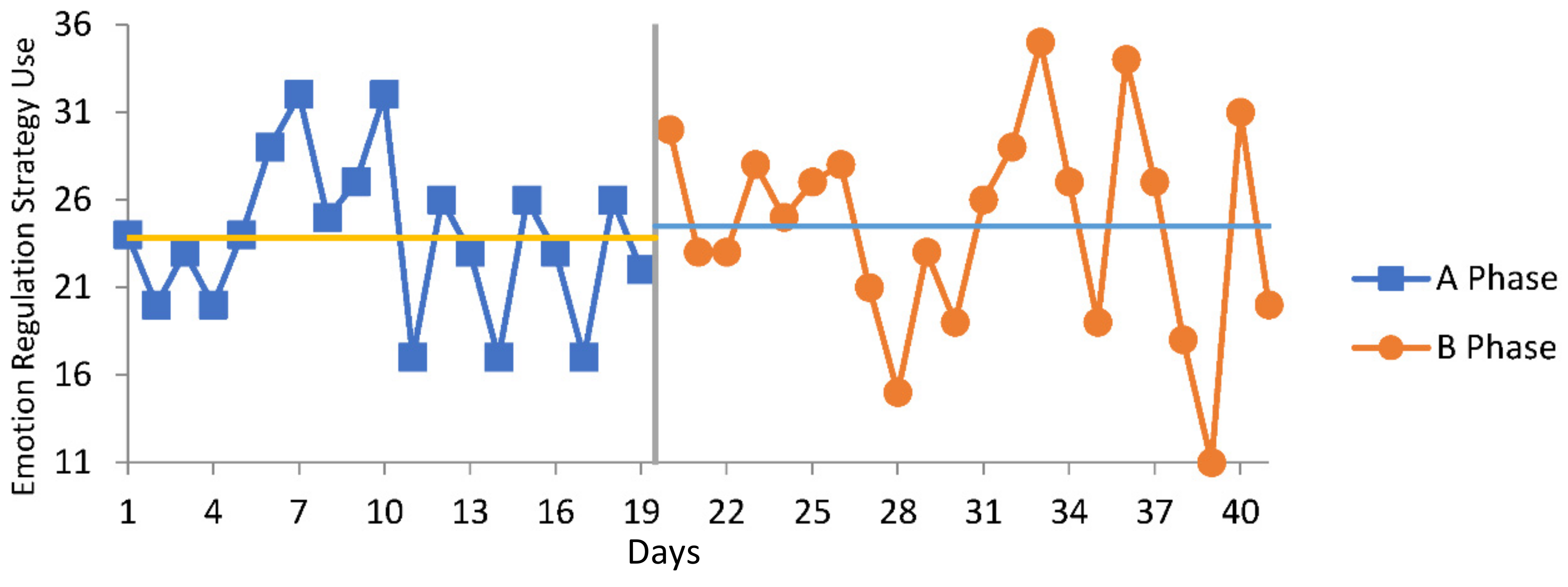

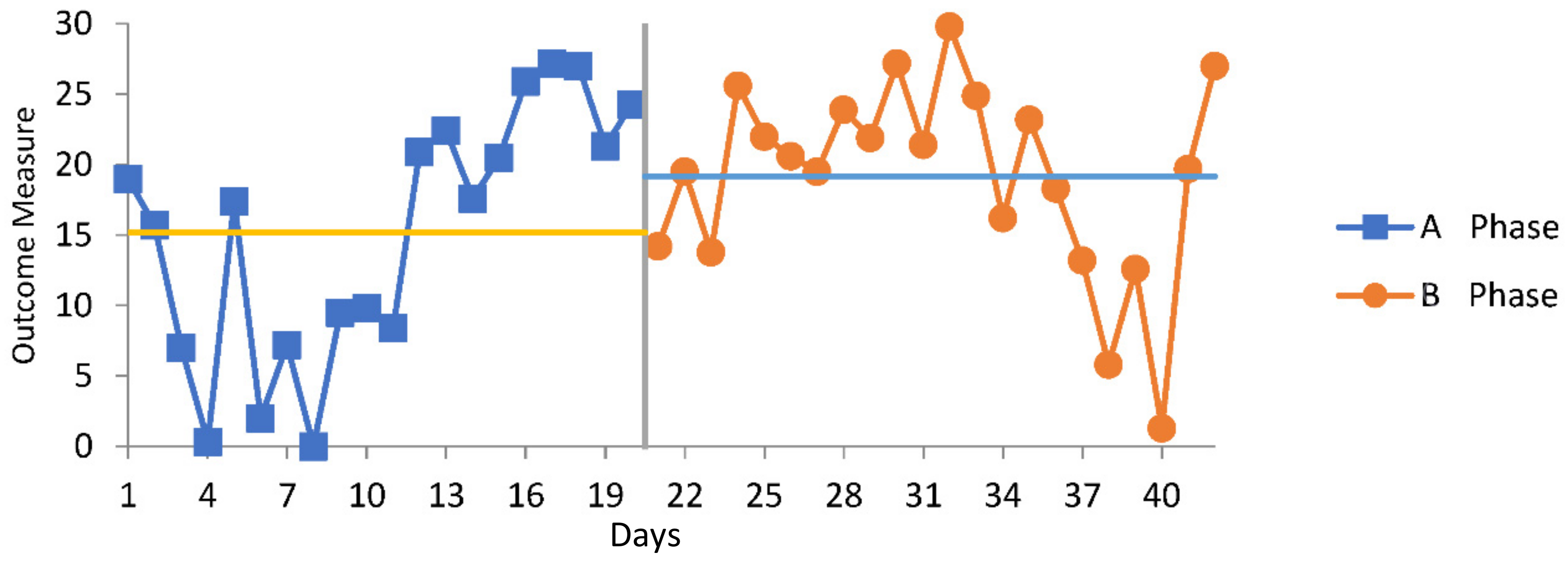

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Emotion Regulation

5.2. Psychological Wellbeing

5.3. Safe Relationships Psychoeducation

5.4. Implications

5.5. Limitations

5.6. Future Directions

5.6.1. Measures

5.6.2. Mixed Methods

5.6.3. Sample

5.6.4. Therapeutic Dose and Follow Up

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Decker, M.; Littleton, H.L. Sexual Revictimization Among College Women: A Review Through an Ecological Lens. Vict. Offenders 2018, 13, 558–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Finkelhor, D.; Jones, L. Improving services for youth survivors of commercial sexual exploitation: Insights from interventions with other high-risk youth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 132, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, M.; Pitcher, C.P.; Saewyc, E. Interventions that Foster Healing Among Sexually Exploited Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2018, 27, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, J.J.; Klettke, B.; Hall, K.; Hallford, D. Toward a Global Definition and Understanding of Child Sexual Exploitation: The Development of a Conceptual Model. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, B.; Collin-Vézina, D. Child Sexual Abuse: Toward a Conceptual Model and Definition. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission for Children and Young People. “…as a Good Parent Would…”: Inquiry into the Adequacy of the Provision of Residential Care Services to Victorian Children and Young People Who Have Been Subject to Sexual Abuse or Sexual Exploitation whilst Residing in Residential Care; Commission for Children and Young People: Canberra, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.; Robinson, B. Tipping the Iceberg: A Pan Sussex Study of Young People at Risk of Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking; Barkingside Essex Barnardos: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Svedin, C.G.; Priebe, G. Selling sex in a population-based study of high school seniors in Sweden: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2007, 36, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, J.J.; Klettke, B.; Hall, K.; Clancy, E.; Hallford, D. Demographic and Psychosocial Factors Associated with Child Sexual Exploitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2017682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, A.G.; Taylor, R.W.; Davis, J.E. Understanding the Complexities of Human Trafficking and Child Sexual Exploitation: The Case of Southeast Asia. Women Crim. Justice 2010, 20, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.K.; Foster, J.M.; Tripathi, N. Child Sexual Abuse in India: Current Issues and Research. Psychol. Stud. 2013, 58, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of State. 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report; US Department of State: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 538.

- Hincks, C.; Winterdyk, J. Integrated Partnerships and Coordinated Wraparound Support: Moving the needle towards effective responses for adolescent victims of sexual exploitation and trafficking in Canadian urban settings. Urban Crime Int. J. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACCCE 2021 Statistics Summary. Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation. 2021. Available online: https://www.accce.gov.au/resources/research-and-statistics/statistics (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Vlerick, M.; Van Hove, J. Revolutionising Digital Sex Work: An Analysis of the Impact of OnlyFans on Sex Workers. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353236967_Revolutionising_digital_sex_work_an_analysis_of_the_impact_of_OnlyFans_on_sex_workers (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Dimitropoulos, G.; Lindenbacha, D.; Devoe, D.J.; Gunn, E.; Cullen, O.; Bhattarai, A.; Kuntz, J.; Binford, W.; Patten, S.B.; Arnold, P.D. Experiences of Canadian mental health providers in identifying and responding to online and in-person sexual abuse and exploitation of their child and adolescent clients. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 124, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, L.; Salter, A. Cosplay on Demand? Instagram, OnlyFans, and the Gendered Fantrepreneur. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joleby, M.J.; Landström, S.; Lunde, C.; Jonsson, L.S.J. Experiences and psychological health among children exposed to online child sexual abuse—A mixed methods study of court verdicts. Psychol. Crime Law 2021, 27, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, C.A.; Alderson, K.; Ireland, J.L. Sexual Exploitation in Children: Nature, Prevalence, and Distinguishing Characteristics Reported in Young Adulthood. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2015, 24, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNICEF. Ending Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse: Lessons Learned and Promising Practices in Low- and Middleincome Countries; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.end-violence.org/knowledge/ending-online-child-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-lessons-learned-and-promising-practices (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Wagner, N.; Armitage, R.; Christmann, K.; Gallagher, B.; Ioannou, M.; Parkinson, S.; Reeves, C.; Rogerson, M.; Synott, J. Rapid evidence Assessment: Quantifying the extent of Online-Facilitated Child Sexual Abuse: Report for the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse; University of Huddersfield: Huddersfield, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.iicsa.org.uk/document/rapid-evidence-assessment-quantifying-extent-online-facilitated-child-sexual-abuse (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Krause-Utz, A.; Dierick, T.; Josef, T.; Chatzaki, E.; Willem, A.; Hoogenboom, J.; Elzinga, B. Linking experiences of child sexual abuse to adult sexual intimate partner violence: The role of borderline personality features, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation, and dissociation. Bord. Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2021, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chohaney, M.L. Minor and adult domestic sex trafficking risk factors in Ohio. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 2016, 7, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naramore, R.; Bright, M.A.; Epps, N.; Hardt, N.S. Youth arrested for trading sex have the highest rates of childhood adversity: A statewide study of juvenile offenders. Sex. Abus. J. Res. Treat. 2017, 29, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; Muñoz, R.F. Emotion Regulation and Mental Health. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1995, 2, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.; Hall, K.; Moulding, R.; Bryce, S.; Mildred, H.; Staiger, P.K. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalley, M. Hidden Abuse–Hidden Crime. The Domestic Trafficking of Children and Youth in Canada: The Relationship to Sexual Exploitation, Running Away and Children at Risk of Harm. Canadian Police Centre for Missing and Exploited Children RCMP: Canada. 2010. Available online: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/cnmcs-plcng/cn30898-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Reid, J.A. An exploratory model of girl’s vulnerability to commercial sexual exploitation in prostitution. Child Maltreat. 2011, 16, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whaling, K.M.; der Sarkissian, A.; Sharkey, J.; Akoni, L.C. Featured counter-trafficking program: Resiliency Interventions for Sexual Exploitation (RISE). Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 100, 104139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaggia, R.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Lateef, R. Facilitators and Barriers to Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) Disclosures: A Research Update (2000–2016). Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, J. Identifying and Disclosing Child Sexual Abuse. 2017. Available online: https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/identifying-and-disclosing-child-sexual-abuse (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Townsend, C. Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure: What Practitioners Need to Know. 2016. Available online: https://www.D2L.org (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Action to End Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/press-centre (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- McElwain AMcGill, J.; Savasuk-Luxton, R. Youth relationship education: A meta-analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, C.J.; Joppa, M.; Barker, D.; Collibee, C.; Zlotnick, C.; Brown, L.K. Project Date SMART: A Dating Violence (DV) and Sexual Risk Prevention Program for Adolescent Girls with Prior DV Exposure. Prev. Sci. 2018, 19, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rue, L.; Polanin, J.R.; Espelage, D.L.; Pigott, T.D. A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Interventions Aimed to Prevent or Reduce Violence in Teen Dating Relationships. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 87, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruhn, M.A.; Compas, B.E. Effects of maltreatment on coping and emotion regulation in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 103, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, D.G.; Bitran, D.; Miller, A.B.; Schaefer, J.D.; Sheridan, M.A.; McLaughlin, K.A. Difficulties with emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic mechanism linking child maltreatment with the emergence of psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavender, J.M.; Tull, M.T.; DiLillo DMessman-Moore, T.; Gratz, K.L. Development and Validation of a State-Based Measure of Emotion Dysregulation: The State Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (S-DERS). Assessment 2017, 24, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, K.; Koval, P.; Verduyn, P.; Lim, Y.L.; Kuppens, P. The regulation of negative and positive affect in daily life. Emotion 2013, 13, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockman, R.; Ciarrochi, J.; Parker, P.; Kashdan, T. Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: Mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2017, 46, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisz, J.R.; Kuppens, S.; Ng, M.Y.; Eckshtain, D.; Ugueto, A.M.; Vaughn-Coaxum, R.; Jensen-Doss, A.; Hawley, K.M.; Krumholz Marchette, L.S.; Chu, B.C.; et al. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 79–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ünlü Kaynakçı, F.Z.; Yerin Güneri, O. Psychological distress among university students: The role of mindfulness, decentering, reappraisal and emotion regulation. Curr. Psychol. J. Divers. Perspect. Divers. Psychol. Issues 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.; Simpson, A.; O’Donnell, R.; Sloan, E.; Staiger, P.K.; Morton, J.; Ryan, D.; Nunn, B.; Best, D.; Lubman, D.I. Emotional dysregulation as a target in the treatment of co-existing substance use and borderline personality disorders: A. pilot study. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, J.J.; Schilpzand, E. InSight: A Therapeutic Resource for Professionals Working with Child Sexual Exploitation; St Kilda Gatehouse: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bjureberg, J.; Ljotsson, B.; Tull, M.; Hedman, E.; Sahlin, H.; Lundh, L.; Bjarehed, J.; DiLilo DMessman-Moore, T.; Gumpert, C.; Gratz, K.L. Development and Validation of a Brief Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: The DERS-16. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2016, 38, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.P.; Naragon-Gainey, K. The Multilevel Structure of Daily Emotion-Regulation-Strategy Use: An Examination of Within- and Between-Person Associations in Naturalistic Settings. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.D.; Duncan, B.L.; Brown, J.; Sparks, J.A.; Claud, D.A. The Outcome Rating Scale: A Preliminary Study of the Reliability, Validity, and Feasibility of a Brief Visual Analog Measure. J. Brief Ther. 2003, 2, 91–98. Available online: https://www.scottdmiller.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/OutcomeRatingScale-JBTv2n2.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Sloan, E.; Hall, K.; Simpson, A.; Yousef, G. An Emotion Regulation Treatment for Young People with Complex Substance Use and Mental Health Issues: A Case-Series Analysis. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2018, 25, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Youseff, G.; Simpson, A.; Sloan, E.; Graeme, L.; Perry, N.; Moulding, R.; Baker, A.M.; Beck, A.K.; Staiger, P.K. An Emotion Regulation and Impulse Control (ERIC) Intervention for Vulnerable Young People: A Multi-Sectoral Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 554100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Child Rights Taskforce The Children’s Report. Available online: http://www.childrights.org.au/resources/law-library/ (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Linehan, M.M. Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-89862-034-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. Introducing Compassion-Focused Therapy. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Harris, B.A.; Eustis, E.H.; Farchione, T.J. The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders; Penguin: London, UK, 1979; ISBN 978-1-101-65988-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chaleff, I. Intelligent Disobedience; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: California, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-62656-427-5. [Google Scholar]

- Domestic Abuse Intervention Project. Teen Power and Control Wheel; National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence: Duluth, MN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, J. Respectful Relationships: Teaching and Learning Package; Department of Education: Tasmania, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Levy, K. Oxford Guide to Behavioural Experiments in Cognitive Therapy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, J.D.; Williams, J.M.G.; Segal, Z.V. The Mindful Way Workbook: An 8-Week Program to Free Yourself from Depression and Emotional Distress; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4625-0814-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness, 15th Anniversary ed.; Delta Trade Paperback/Bantam Dell: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume xxxiii, p. 471. ISBN 978-0-385-30312-5. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Federal Police Preventing Online Child Sexual Exploitation. Available online: https://www.thinkuknow.org.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/Fact%20sheet%20Preventing%20online%20child%20sexual%20exploitation.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Hayes, S.C.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. In Psychotherapy Theories and Techniques: A Reader; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-1-4338-1619-2. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, D.; Furman, W.; Wittenberg, M.T.; Reis, H.T. Five Domains of Interpersonal Competence in Peer Relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, L.; Wekerle, C.; Goldstein, A.L. Measuring Adolescent Dating Violence: Development of “conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory” Short Form. Adv. Ment. Health 2012, 11, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafurov, B.; Levin, J. EXPRT (Excel® Package of Randomization Tests): Statistical Analyses of Single-Case Intervention Data 2021. Available online: https://github.com/gsborisgithub/ExPRT (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Edgington, E.S. An Additive Method for Combining Probability Values from Independent Experiments. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 1972, 80, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.; Mendoza, J.L. A Method of Assessing Change in a Single Subject: An Alteration of the RC Index. Behav. Ther. 1986, 17, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Truax, P. Clinical Significance: A Statistical Approach to Defining Meaningful Change in Psychotherapy Research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, W.J.; Arrindell, W.A. A Further Refinement of the Reliable Change (RC) Index by Improving the Pre-Post Difference Score: Introducing RCID. Behav. Res. Ther. 1993, 31, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Statistics. Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-002705-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bounds, D.T.; Otwell, C.H.; Melendez, A.; Karnik, N.S.; Julion, W.A. Adapting a Family Intervention to Reduce Risk Factors for Sexual Exploitation. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.C. Featured Counter-Trafficking Program: Trauma Recovery for Victims of Sex Trafficking. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 100, 104153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, M.R.H.; Goff, B.S.N. Initial Treatment Decisions with Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse: Recommendations from Clinical Experts. J. Trauma Pract. 2006, 5, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Participant 1 | Participant 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18 | 18 |

| Sex | Female | Female |

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | Lesbian |

| Place of birth | Australia | Australia |

| Educational attainment | Year 10 | Year 10 |

| Current education engagement or employment | /No | Yes |

| Relationship status | Yes, Boyfriend | Yes, Girlfriend |

| Experience of CSE | Yes, at <15 years of age | Yes, at <15 years of age |

| Co-morbidities | No | PTSD * |

| Emergency department admission (last 12 months) | No | Yes, suicide attempt |

| Ever experienced homelessness | No | Yes, at age 15 |

| Engaged with foster care system | No | No |

| A parent themselves | No | No |

| Contact with the police in the past two weeks | No | Yes |

| Intervention Target | Worksheets | Exercises | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human rights and needs | Human Needs | Psychoeducation to normalize safety as a human right and need for children and young people. Practice identifying needs that are fulfilled and those that are unmet. Reflection regarding what safety means. | Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs [53]. National Children’s and Youth Law Centre [54]. |

| Self-Care and Self-Compassion | 5 Self-Care Habits | Developing a self-care plan that involves reaching out to others, exercising, and sleeping well, being mindful, eating well and being kind to yourself and others. | DBT self-soothing [55]. Compassion Focused Therapy [56]. |

| Emotional literacy | Why should I regulate Dissecting your feelings | Psychoeducation and insight building into current patterns of emotion regulation A functional analysis of physical sensations, emotions, urges, cognitions, and behaviors during a chosen situation. | The Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders [57]. A CBT based functional or chain analysis [58]. |

| Power differentials in relationships | Doing what I need (Blink, Think, Choice, Voice) Power and Control | A mnemonic for teaching young people about intelligent disobedience and how to apply it in relationships when disobeying is the right thing to do. Creating awareness of power differentials in the context of all sorts of safe and unsafe relationships. | Intelligent disobedience [59]. Duluth model of power and control [60]. |

| Consent | Consent on or offline | Psychoeducation regarding consent, encompassing discussions of verbal yes, no coercion and within the context of equality. | Respectful Relationships: Teaching and Learning Package [61]. |

| Behavioural Avoidance | Facing up to avoidance | Developing a behavioral experiment to engage in graded exposure to a situation that has been avoided. | A CBT based behavioral experiment [62]. |

| Acceptance | Allow space for all your feelings | Identification of emotions that are currently avoided and a graded exposure plan to experience them a little bit each day. | CBT for emotional disorders [58]. |

| Interpersonal skill–boundaries | Boundaries Insight Cards | Using a set of visual images depicting safe and unsafe relationships to reflect on boundaries on and offline. Differentiating between no boundaries, uncertain boundaries, and healthy boundaries. | Interpersonal effectiveness skills from DBT [55]. Respectful Relationships: Teaching and Learning Package [61]. |

| Distress Tolerance | Shake off feelings | Develop a behavioral plan that allows cognitive disputation of thoughts and behaviors that perpetuate a negative emotional state. | Opposite action, distress tolerance skill from DBT [55] and CBT based behavioral experiments [62]. |

| Mindfulness | Mindful breathing Mindful lean | Using the spotlight of attention to aid mindful breathing Using the feet and toes to help check in with the present moment. | Three-minute breathing space [63]. Physical sensations in mindfulness [64]. |

| Sexual violence awareness and reporting | Sexual Exploitation | Exploring what constitutes CSE, watching a 3-min video of a victim-survivor’s experience, exploring accessible support services and reporting both online and offline. | Preventing online child sexual exploitation [65]. Respectful Relationships: Teaching and Learning Package [61]. |

| Values and identity | No matter how you feel, do what matters to you | A metaphor of passengers in a minivan to represent cognitions and emotions that are commonly avoided and a road trip to represent value- based action. | Passengers on a bus metaphor from ACT [66]. |

| DERS-16 | ORS | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Clinical mean, M0 | 33.57 | 28.00 |

| Clinical mean, M1 | 57.00 | 19.60 |

| Non-clinical SD, S0 | 13.14 | 6.80 |

| Clinical SD, S1 | 13.05 | 8.70 |

| Reliability, rsx | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| a Standard error of measurement, SE | 3.32 | 2.30 |

| b Cut off for clinically significant change | 45.32 | 23.29 |

| Participant | Control Mean | ERIC + YR M | Control Phase SD | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Regulation Strategy Use (Daily ERSS Total Score) | ||||

| P1 | 16.83 | 17.95 | 1.87 | 0.60 ns |

| P2 | 23.84 | 24.50 | 4.48 | 0.15 ns |

| Psychological Wellbeing (ORS Total Score) | ||||

| P1 | 29.10 | 27.62 | 1.96 | −0.75 ns |

| P2 | 15.17 | 19.16 | 8.95 | 0.45 ns |

| Relationship Safety Knowledge (RSS item) | ||||

| P2 | 2.53 | 3.10 | 1.07 | 0.53 ns |

| Participant 1 (P1) | Participant 2 (P2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Daily emotion regulation strategy use (ERSS) 1 | 18 | 18 | 24 | 20 |

| Emotion dysregulation symptoms (DERS-16) | 19 | 34 *,# | 56 | 40 |

| Psychological wellbeing (ORS) | 27 | 32 | 19 | 27 *,# |

| Interpersonal competence (ICQ) | 54 | 61 | 71 | 77 |

| Relationship safety knowledge and behaviour (RSS) | 36 | 41 | 34 | 44 |

| Conflict in dating relationships (CARDIS) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laird, J.J.; Klettke, B.; Mattingley, S.; Hallford, D.J.; Hall, K. A Single-Case Series Trial of Emotion-Regulation and Relationship Safety Intervention for Youth Affected by Sexual Exploitation. Psych 2022, 4, 475-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4030037

Laird JJ, Klettke B, Mattingley S, Hallford DJ, Hall K. A Single-Case Series Trial of Emotion-Regulation and Relationship Safety Intervention for Youth Affected by Sexual Exploitation. Psych. 2022; 4(3):475-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4030037

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaird, Jessica J., Bianca Klettke, Sophie Mattingley, David J. Hallford, and Kate Hall. 2022. "A Single-Case Series Trial of Emotion-Regulation and Relationship Safety Intervention for Youth Affected by Sexual Exploitation" Psych 4, no. 3: 475-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4030037

APA StyleLaird, J. J., Klettke, B., Mattingley, S., Hallford, D. J., & Hall, K. (2022). A Single-Case Series Trial of Emotion-Regulation and Relationship Safety Intervention for Youth Affected by Sexual Exploitation. Psych, 4(3), 475-493. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4030037