Abstract

Background: Relationship satisfaction has been identified as an important factor in terms of extradyadic sexual involvement. However, in men, fatherhood might be associated with infidelity by leading to changes in relationship satisfaction and the social life of parents. To date, no study has focused on the association of fatherhood and infidelity, nor the influence of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity. Methods: Using a cross-sectional design, 137 fathers and 116 non-fathers were assessed regarding relationship satisfaction, infidelity, and potential confounds. Results: Significantly more fathers reported having been unfaithful in the current relationship than non-fathers (30.7% vs. 17.2%). Fathers also reported longer relationship duration, higher relationship satisfaction, and lower neuroticism than non-fathers. Furthermore, fatherhood moderated the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity insofar that only in non-fathers reduced relationship satisfaction was associated with infidelity. Conclusions: The results suggest that fatherhood increases the risk of engaging in extradyadic sexual activities and moderates the link between relationship satisfaction and infidelity. However, results need to be interpreted with caution due to the cross-sectional study design and the lack of information about the specific time point of the infidelity incident(s).

1. Introduction

Myriad films, TV series, songs, and books are devoted to the theme of love and infidelity, which is a violation of a core principle of monogamy. However, risk and protective factors of infidelity, as well as the underlying mechanisms leading to infidelity, are insufficiently understood. Monogamy denotes the mutual decision to commit to one specific partner sexually and relationally [1], and this relationship style is widely practiced in diverse societies. Dush and Amato (2005) showed that committed and monogamous relationships are associated with increased subjective wellbeing with the measure consisting of life satisfaction, general happiness, distress symptoms, and self-esteem. Overall, the majority of people perceive monogamy to be beneficial and desirable [1,2,3].

Infidelity (or synonyms thereof such as cheating or unfaithfulness) constitutes a serious issue in exclusive romantic relationships. It is negatively associated with relationship satisfaction, causes strain, and threatens the continuation of the relationship [4]. Recent findings even point out that higher ratings of relationship quality, including relationship passion, can decrease the desire for extramarital sex [5]. This indicates that relationship satisfaction influences the desire for extradyadic sex. Moreover, infidelity is one of the leading causes of divorce [6,7]. Indeed, an association between infidelity and strain even persists after controlling for marriage quality [8]. The prevalence of male infidelity in heterosexual couples ranges from around 20% to over 50% (e.g., [9]). Although infidelity has been reported to be higher in men than in women [10], some studies have questioned this perspective, revealing similar rates of infidelity for both genders [11]. To our knowledge, no study has examined infidelity rates in Switzerland. Nevertheless, a German representative study reported the lifetime prevalence of infidelity among heterosexual men to be as high as 49% [12]. Another study found infidelity rates of 17–32% for heterosexual men in Germany [13]. In a German representative sample, 83% of men indicated that fidelity in general is important for their relationships [14]. Taken together, infidelity is widespread and most people consider it to be harmful to intimate relationships.

Based on the investment model, it has been theorized and repeatedly shown that individuals in more satisfying relationships are more likely to be committed and less likely to seek alternative partners [15,16]. Therefore, relationship satisfaction emerges as a crucial factor for predicting infidelity with reduced satisfaction increasing the risk of seeking alternative partners and thereby engaging in infidelity [17,18]. The mate switching hypothesis focuses on the practice some individuals have, leaving one relationship and entering another, potentially even having cultivated the new partner during the past relationship [19]. However, not every extradyadic sexual activity is committed with regard to finding a new partner. Other relationship designs, such as consensual non-monogamy, do also exist and have previously been found to be associated with better satisfaction with communication within the relationship than monogamous relationships and higher general relationship satisfaction [20]. However, the present examination focuses on monogamous relationships since this represents the wide practice across almost all societies. Further, some studies have investigated infidelity as a construct comprised of emotional and sexual infidelity. Walsh et al. [21] defined emotional infidelity as having “no sexual contact but a romantic emotional attachment” and sexual infidelity as “being sexually involved with a person other than their current partner”. The present investigation focuses explicitly on sexual infidelity [22].

Referring back to the investment model that identified relationship satisfaction as a crucial factor in infidelity research, the transition to fatherhood and general status of being a father have emerged as potentially relevant variables. Fatherhood is generally associated with large investments in the partner relationship with regard to the often assumed role as provider for the family or his involvement in the family [23]. However, in a considerable portion of men, fatherhood generates distress [24]. Fatherhood has been suggested to contribute to infidelity, as indicated by the higher divorce rates among parents compared to married couples without children [25]. For men, becoming a father is a critical life event, which causes several changes in terms of a couple’s relationship, mental health, financial and time resources, and social roles. Longitudinal studies revealed that, during the transition to fatherhood, relationship satisfaction, relationship quality, and sexual satisfaction decreased [26,27]. Moreover, the literature has consistently reported that fathers often experience distress and strain, which can further decrease relationship satisfaction and lead to infidelity [28,29]. Furthermore, while it has long been suggested that the transition to fatherhood increases commitment, a more recent study found no such increase, and instead reported stable levels of commitment for married couples and a decrease in commitment for cohabiting non-married couples [30]. Importantly, in a sample comprised of relatively young unmarried individuals between the ages of 18 and 35, besides other sociodemographic variables, having a child was not related to extradyadic sexual involvement [31]. However, due to the study design, there was a very small portion of fathers examined and no further analyses with regard to fatherhood status, infidelity, and relationship satisfaction were conducted. Other studies have examined the link between extramarital engagement and the number of children, revealing no association [32,33,34]. However, these studies did not capture the dichotomous nature of parenthood or fatherhood status, instead implying a dose-response relation with more children assuming more infidelity, which was not supported by the data.

Importantly, the prevalence rates of infidelity describe a curvilinear association with age, showing a steady increase before reaching a peak around 50 years, followed by a gradual decline thereafter [17,35]. Wiederman [35] found the highest rates of infidelity within the past year for 30–39-year-old men, but reported overall infidelity rates in line with Greeley [17]. The average age of Swiss men to become a father for the first time is around 35 years of age, indicating a reduced relationship satisfaction in many men during this period and an increased risk for infidelity. A national survey from the United States suggested a U-shaped association between the likelihood of extramarital sex and marital duration in men with a nadir after 18 years [34]. Another aspect is that, due to age-related biological changes such as testosterone decline, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction increases in middle-aged and older men [36,37,38], and pharmaceutical treatments for these sexual dysfunctions and related symptoms might increase male sexual activity and infidelity [39,40,41,42]. This is important since the current study includes elderly participants. Bloom et al. [25] further found that infidelity increases with longer relationship duration. This is particularly important because, in the face of low relationship satisfaction, partners with a child are often more hesitant to break-up than partners without children [43]. Therefore, age and relationship duration are also important factors to consider when investigating the link between fatherhood and infidelity. However, the relation between fatherhood, infidelity, and relationship satisfaction has never before been the focus of a study.

Nevertheless, infidelity has been investigated in various forms of exclusive heterosexual romantic relationships, such as marriage and long- or short-term relationships. As such, several further potential predictors of infidelity were identified [44]. Personality factors, such as the Big Five [45], were related to infidelity, showing that low scores on agreeableness and conscientiousness were associated with increased rates of infidelity [46]. In addition, increased sensation seeking and impulsivity and reduced perspective taking were identified as factors to explain engagement in infidelity [47]. Thus, personality research on infidelity indicates that, in addition to reduced conscientiousness and agreeableness, factors such as impulsivity are relevant facilitators of unfaithful behavior. In addition, national representative survey data from the US reveal that a higher likelihood of infidelity is associated with stronger sexual interests, more permissive sexual values, lower relationship satisfaction, and greater sexual opportunities [17]. Furthermore, in a sample of undergraduate college students, increased alcohol consumption was associated with extradyadic sexual involvement [48]. Interestingly, in a multivariate contextual analysis in heterosexual college students, of the examined set of variables including relationship satisfaction, relationship duration, alcohol consumption, attachment styles, and symptoms of depression, only reduced relationship satisfaction and an insecure attachment style were associated with increased infidelity [18]. Sociosexual behavior—i.e., the disposition to engage in uncommitted sexual encounters—has been shown to be associated with the likelihood to stay single or to be in a relationship [49] and was consistently associated with infidelity [49,50,51]. Studies uncovered that individuals who separated showed equally high sociosexual behavior as singles. Sociosexual behavior can therefore be understood as another predictor of infidelity. This is especially relevant when discussing infidelity-driven theories such as the partner switching hypothesis [19] or the investment model [15,16]. Importantly, in a previous examination conducted by our group, higher testosterone levels were identified to be associated with increased infidelity in healthy men, while relationship satisfaction, depressive and sexual symptoms, as well as alcohol consumption differed significantly between faithful and unfaithful men [52].

Other studies have also examined indirect effects with regard to infidelity and related behavior as dependent variables, which is important since the present study further examines the moderating effect of fatherhood with regard to relationship satisfaction and infidelity. For example, Weiser et al. [53] reported that parental marital status moderates the association between parental infidelity and offspring infidelity. However, Clayton [54] investigated a moderated mediation including the moderation effect of relationship length on the indirect association of social media use, social media-related conflict, and negative relationship outcomes (such as infidelity), and were unable to confirm the moderation-mediation model. Although findings regarding infidelity and its determinants are inconsistent, relationship satisfaction emerges as the most consistent predictor of infidelity and research highlights that the risk of infidelity increased 4-fold in couples who reported low relationship satisfaction compared to couples who reported high relationship satisfaction [55]. However, the referenced studies were comprised of heterogeneous samples including both genders or predominantly student samples in their analyses. Since gender differences are observed in infidelity rates, gender-specific analyses are needed to identify the specific predictors of infidelity for clearly defined subgroups such as healthy men.

To date, no study has investigated the association between infidelity and fatherhood in depth. Moreover, research regarding the effect of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and engaging in extradyadic sexual activities is also lacking. Based on the above, we hypothesize that extradyadic sexual involvement occurs more often in fathers than non-fathers due to the increased strain within the partner relationship and the subsequently reduced relationship satisfaction. In addition, we hypothesize that fatherhood moderates the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Matching of Datasets

For the current study, two distinct datasets were merged in order to maximize the number of participants, to increase statistical power, generalizability, and to enable the examination of fathers in contrast to non-fathers. This was done, since to date there is no data specifically examining infidelity in relation to fatherhood. The two datasets used are from studies that examined only men and stem from the same research department. The same psychometric instruments were used in both studies to measure relationship satisfaction, personality, and infidelity. One study focused on aspects of paternity and mental health and provided mainly male subjects of the father group, while the other study focused on general health aspects of men and provided mainly subjects of the non-father group. One study investigated the effects of fatherhood and family composition on psychological well-being in 3616 men with an age range of 19 to 72 years [24]. Participants were recruited via online advertisements, newspapers, and broadcasts. Inclusion criteria were being a biological male, being an adult (18 years at least), and having assumed the paternal role for at least one child. The other study, the Men’s Health 40+ study, examined 271 men (age range 40–75 years) with an emphasis on biopsychosocial factors of healthy aging [56]. Participants were recruited via online advertisements, mailing lists of companies, and information events. Participants completed an online survey for the study with questionnaires and a biological assessment in the laboratory of the University of Zurich. Inclusion criteria were being between 40 and 75 years of age, exhibiting no psychiatric disorders, no usage of psychopharmacotherapy, self-rated physical health of at least “good”, having no acute or chronic physical diseases, and no illegal drug use. Both studies were conducted in Switzerland and participants were predominantly white. To prevent confounding, the data from the two studies were matched with regard to age. The matching was successful with regard to age. Further analyses revealed differences for length of relationship (t (271.954) = 4.196, p < 0.001), neuroticism (t (217.573) = −2.278, p = 0.024), relationship satisfaction (t (272) = 2.827, p = 0.005), marital status (U = 5642, z = −5.929, p < 0.001), and income (U = 7683, z = −2.256, p = 0.012). By contrast, no differences emerged for extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, mental health, or body mass index. The final analyzed sample comprised of 253 age-matched men, including 137 fathers and 116 non-fathers. It is important to note that the Waldvogel and Ehlert study [24] only investigated fathers, whereas the Walther et al. study [56] included both fathers and non-fathers. However, fathers from both studies were included in the final sample in order to produce a more heterogeneous sample. All participants provided written consent for their data to be used for scientific purposes prior to each study.

2.2. Measures

Participants completed the German version of the Relationship Assessment Scale [57], a short questionnaire assessing relationship satisfaction. Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1–5, with 5 indicating higher relationship satisfaction. In addition, participants were asked whether they engaged in extradyadic sexual actions: “During your current relationship, have you ever had sexual contacts with people outside of this relationship that were not agreed upon with your partner?”. Participants could choose between the response options “no”, “rarely”, “occasionally”, and “regularly”. Since the answering of this question can potentially cause social desirable answers, we decided to implement a specific method from the social sciences to anonymize the answers and apply a check for social desirability in the answers to the question about infidelity. This delicate question was asked in two different ways: First, participants were directly asked about infidelity. This enabled us to calculate all results for the current study. To test the social desirability of our participants, we also applied an indirect method to assess infidelity. We employed an indirect, crosswise method based on probability calculations, which is described in greater detail elsewhere [58]. This crosswise method was used to enable an indirect measurement of infidelity without the ability to trace back the answer to one specific individual, thus minimizing aforementioned social desirability. It is important to note, however, that this crosswise method only enabled us to calculate infidelity rates over the complete sample, not individual answers. In brief, participants had to answer two questions. The first question asked whether the respondents’ mother was born in January or February, to enable a later calculation of the percentage for the infidelity question. This measure is widely used in social desirability skewed topics throughout the social sciences. Participants were instructed to remember their answer (yes or no). The probability of a birth in January or February is 16.6% (the authors of this approach assume equal probabilities for births over the year). The second question asked about infidelity in the participants’ current relationship. Participants were again instructed to remember their answer (yes or no). Participants then indicated in the questionnaire whether or not the two answers (to the birth month and the infidelity question) were identical, i.e., yes to both questions or no to both questions, and whether the answers were not identical (i.e., yes/no, no/yes). The known probability of the first question enabled the calculation of percentages of the answers to the infidelity question. Subsequently, the crosswise incidence of infidelity was computed using probability calculations according to the instructions of Jann et al. [58]. This opened up the possibility to answer anonymously, without the possibility to trace back an individual answer to one participant, since only a sample-wide prevalence can be calculated. The following formula was applied: Percentage of identical answers (x) plus probability of being born in January or February (2/12) divided by two times the probability of being born in January or February minus 1. Therefore, the mathematical formula was: û = (x + 2/12 − 1)/(2 × 2/12 − 1). Furthermore, participants completed the German short version of the Big Five Inventory BFI-K, [59] to assess personality traits and the German version of the Brief Symptom Inventory BSI-18, [60] to assess mental health, and in order to control for possible confounding factors between the two datasets. The BSI-18 comprises the subscales depression, somatization, anxiety, and a general score, while the Big Five Inventory comprises the subscales neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness. Additionally, participants’ BMI was measured as a marker of health and an indirect measure of body composition and shape.

2.3. Data Analysis

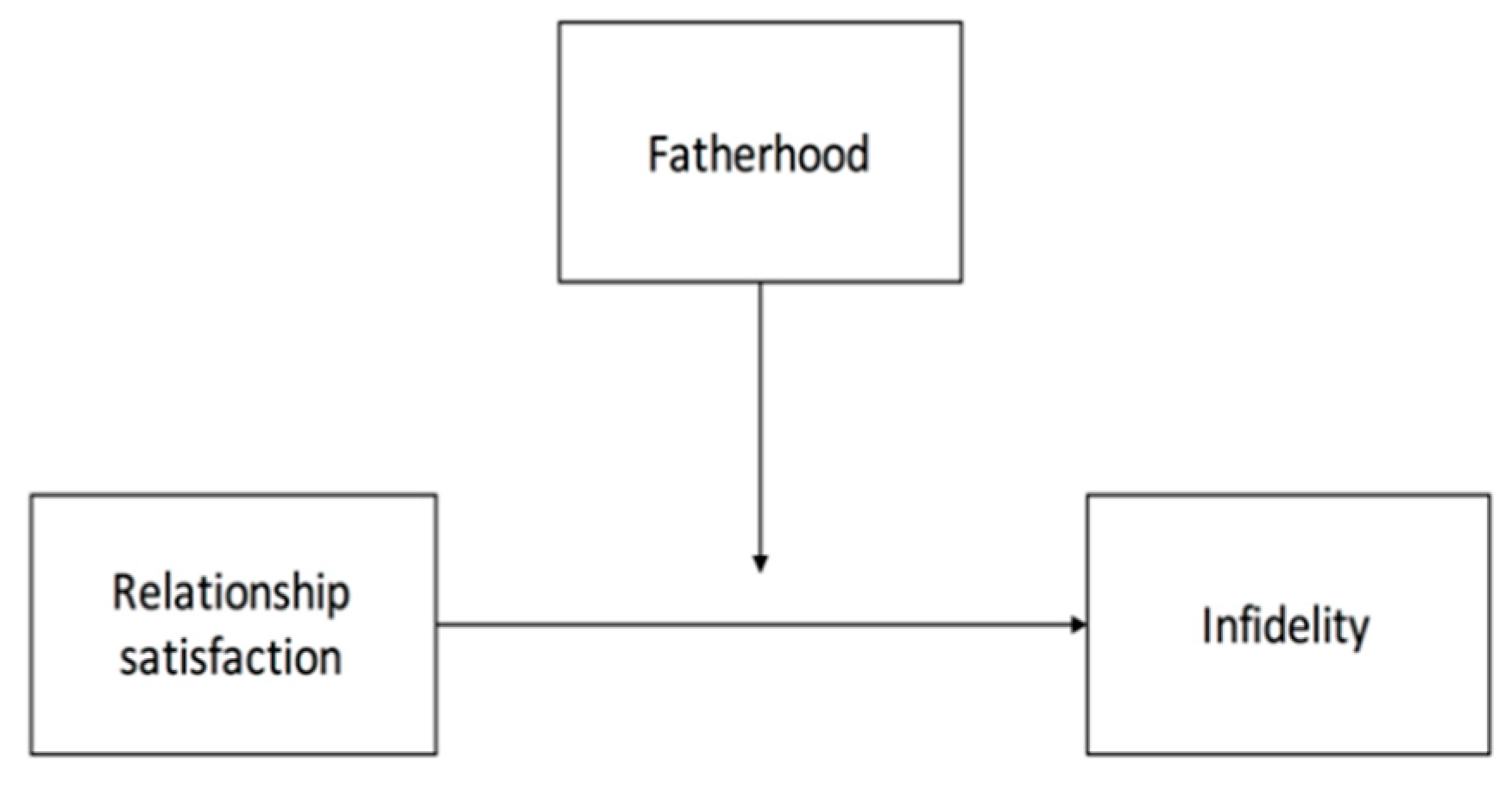

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS ® (IBM Statistics, Version 23.0. IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015). First, descriptive data were calculated, followed by group comparisons between fathers and non-fathers. Depending on the scale, the group comparisons were conducted using t-tests for independent samples or non-parametric tests (i.e., Mann–Whitney U test). In addition, correlation analyses were conducted. The moderation analysis was performed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro version 2.1.6 [61]. The moderation model used was model 1 of the PROCESS macro, which is also indicated in an adapted form in Figure 1. Due to the nature of the data, we applied a logistic regression approach for the moderation analysis. Moderation analyses were conducted using bootstrapping with 5000 samples [61]. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Theoretical moderation model of the influence of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

As shown in Table 1, the participants’ mean age was 47.5 years. All participants reported that they were in a heterosexual relationship defined as monogamous. Notably, for fathers, the female partner in the current relationship did not necessarily need to be the mother of the fathered child or children. The mean level of relationship satisfaction for the sample was M = 4.1 (SD = 0.7). On average, participants’ relationship duration was 13.6 years. With regard to the number of children, 45.8% reported having no children, 17.4% reported having one child, 28.5% reported having two children, 7.9% reported having three children, and 0.4% reported having four or more children. When asked directly about infidelity, 24.5% reported having engaged in extradyadic sexual activities during the current relationship and 75.5% did not. Most of the participants who engaged in extradyadic sexual activities reported doing so rarely (17.8%), 5.9% reported occasional extradyadic sexual activities, and 0.8% reported engaging in extradyadic sexual activities regularly. Using the indirect questioning technique, 30.1% of participants were calculated to engage in extradyadic sexual activities.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the sample.

3.2. Group Comparison

The results showed no significant differences regarding age, body mass index, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness, and mental health. However, fathers reported significantly longer relationships (t (251) = −4.189, p < 0.001), lower neuroticism (t (224) = 2.272, p = 0.024), and higher relationship satisfaction (t (251) = −2.654, p = 0.008) than non-fathers. Non-parametric tests were used for group comparisons of ordinal data such as education, income, and frequency of infidelity. There was no significant difference between the groups regarding education (U = 8366.500, z = 0.975, p = 0.3299), whereas significant differences emerged regarding income (U = 6365, z = −2.813, p = 0.005), and infidelity (U = 8985, z = 2.386, p = 0.017).

Differences in the prevalence of infidelity were calculated regarding the two groups of men and the two infidelity measures (direct and indirect). For the entire sample, an infidelity prevalence of 24.5% was observed with direct questioning, while the indirect questioning resulted in a prevalence of 30.2%. When questioned directly, 17.2% of the non-fathers stated that they engaged in extradyadic sexual activity, whereas 82.8% did not. However, when questioned indirectly, 21.8% of the non-fathers reported having engaged in extradyadic sexual activity. For the fathers, direct questioning resulted in 30.7% reporting that they had been unfaithful during the current relationship, while 69.3% reported that they were faithful. It is important to note here that none of the fathers reported engaging in extradyadic sexual activities regularly. However, when questioned indirectly, 35.9% of the fathers reported having engaged in extradyadic sexual activities.

Regarding correlation analyses of age and infidelity, the correlation was significant both for fathers and for non-fathers. Correlation analyses were conducted using point-biserial correlation. Age and infidelity were correlated at rs = 0.179 (p = 0.004) for the entire sample, while length of the current relationship and infidelity were correlated at rs = 0.128 (p = 0.041). In fathers age and infidelity were correlated at rs = 0.231 (p = 0.007), while length of the current relationship and infidelity were not correlated (rs = −0.027, p = 0.752). In non-fathers, age and infidelity were not correlated (rs = 0.081, p = 0.386), while length of the current relationship and infidelity were correlated (rs = 0.282, p = 0.002). However, when concomitantly controlling for either age or the length of the relationship, the correlations became non-significant except for the correlation between age and infidelity controlled for length of the relationship in fathers (rp = 0.254, p = 0.003), suggesting a robust positive correlation of age and infidelity in fathers.

3.3. Moderation Analysis

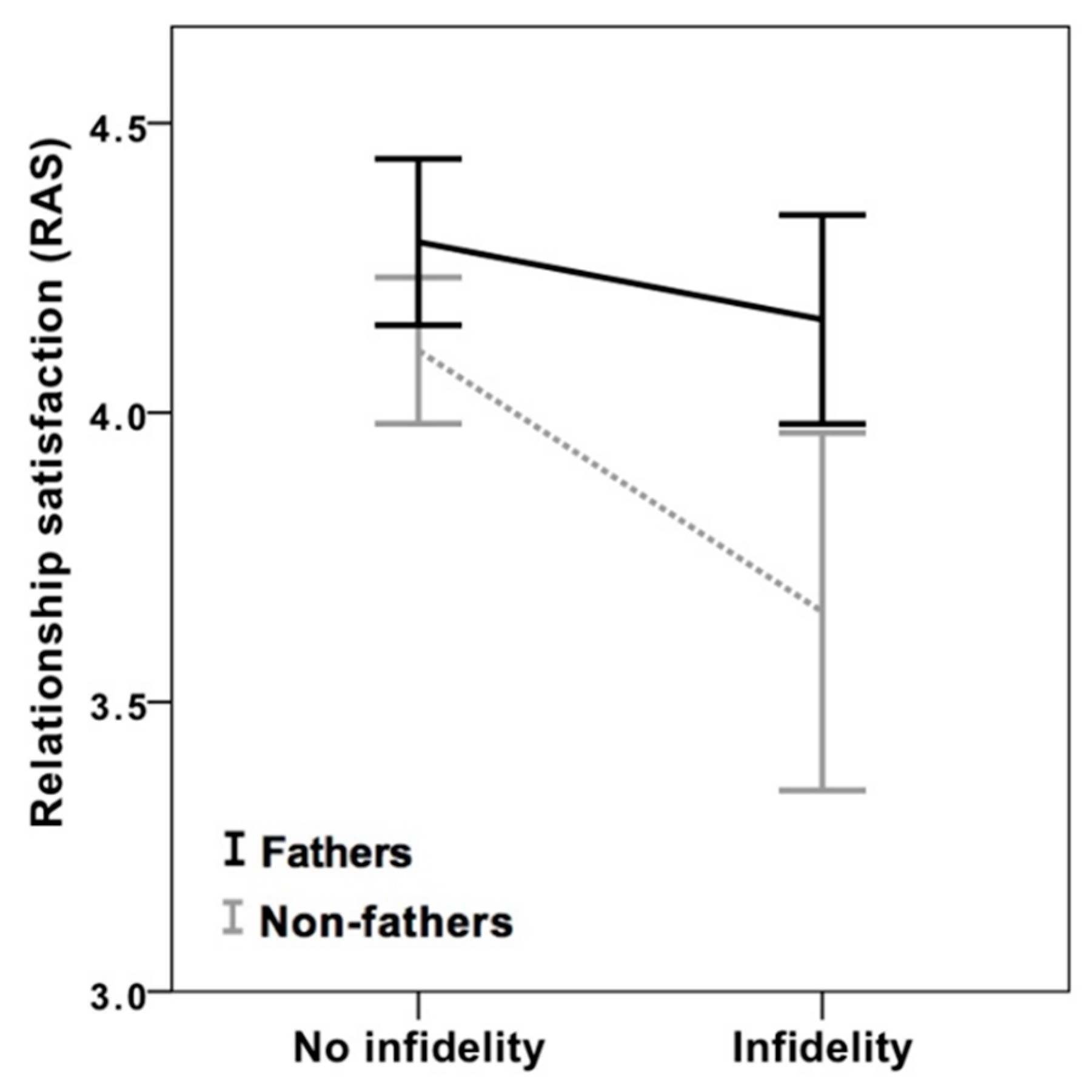

A logistic regression approach was used for the moderation analysis with the dependent variable being binary indicating infidelity (positive vs. negative). Moderation analysis examining the effect of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity yielded a significant model (p < 0.001, Nagelkerke r2 = 0.17) and revealed a significant interaction term (b = 1.145 (CI: 0.219–2.071), se = 0.473, z = 2.422, p = 0.015). The moderation analysis was controlled for age, education, number of children, relationship length, and marital status. Except for the interaction term only the conditional effect [62] of relationship satisfaction on infidelity was significant (b = −1.3711, se = 0.386, z = −3.554, p < 0.001). The moderation model and the interaction effect remained significant even after additionally controlling for the factors neuroticism or income. As shown in Figure 2, the significant moderation effect of fatherhood suggests that there is only in non-fathers a negative association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity but not in fathers.

Figure 2.

Moderation effect of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between fatherhood and infidelity, as well as the effect of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity. Since infidelity is one of the leading causes of relationship termination causing severe psychological distress in many individuals [6]. This issue is highly relevant in order to achieve a better understanding of the determinants leading to infidelity and to foster the prevention of infidelity.

The results showed increased infidelity in fathers as compared to non-fathers. This is surprising at first glance when considering the investment model, which suggests high investment and commitment for the relationship in fathers resulting in higher relationship satisfaction and a reduced risk for infidelity [15,16]. Previous research also indicates no association between the number of children or parenthood and infidelity, although the available studies are either limited to non-married individuals, used the actual number of children as predictors, while none of the studies focused on fatherhood, relationship satisfaction, and infidelity [31,32,33,34]. However, relationship satisfaction of the couple commonly declines as soon as the child is born [26,27,63]. Furthermore, fathers show an increase in depressive symptoms during the first phase after birth and a residual amount of symptomatology over the first seven years of their child’s life [64,65,66]. We argue that during this time, when the child needs a lot of the parental attention and the relationship satisfaction of the couple is challenged, men are at an increased risk for infidelity. This is supported by research showing couples transitioning to parents. For men, the frequency of sex is significantly more relevant than for women and that infrequent sex is associated with sexual and relationship dissatisfaction in men, but not women [67]. Although, it is known that paternity has several negative consequences for the relationship and the sexual life of fathers and mothers, this is more likely in couples with small children, while couples with older children such as eight years or older do not experience the same challenges anymore and regain some of the lost relationship and sexual satisfaction [63]. On the other hand, it has also been suggested that in couples without children, relationship satisfaction is very low, the relationship is terminated more quickly, while parents are more likely to stay together despite difficulties for the sake of the children [68]. However, this in turn might be associated with an increased risk of infidelity in fathers during difficult relationship periods. Unnoticed needs of fathers during the transition to fatherhood may thus lead to reduced relationship satisfaction resulting in an increased risk for infidelity.

In the present study, fathers showed higher relationship satisfaction than non-fathers. This contradicted previous research, which showed reduced relationship satisfaction in couples transitioning to parents or with young children [26,27,69]. However, our findings support a previously identified U-shaped relation between relationship satisfaction and age of the children in fathers with a decreased relationship satisfaction after birth of the first child and an increase after the child’s age of eight years [63,70]. When considering the characteristics of the present sample (e.g., average age of 47.5 years, average duration of intimate relationship 13.6 years, most of the fathers fathering two or more children), it was evident that many fathers were in the later phase of fatherhood, where relationship satisfaction increased again and even surpassed the relationship satisfaction of the childless couples [70]. Taking another perspective, extramarital sexual activities might positively influence relationship satisfaction in fathers. One could hypothesize that the higher relationship satisfaction for fathers, despite higher rates of infidelity, represents a cognitive coping mechanism to diminish cognitive dissonance after engaging in extramarital sexual activities. Moreover, a form of idealization of the family might play an important role here, since several of the included fathers were part of a study specifically focused on fatherhood [24]. A further possible explanation for the incongruent finding is that lower sexual satisfaction within the relationship may be compensated by extradyadic sexual activity [71]. This, in turn, might result in higher relationship satisfaction within the primary relationship due to the fulfillment of the aspired sexual activity. However, this explanation does not take into account feelings of guilt, and further research is therefore needed to clarify whether guilt has an impact on this association.

In addition, the results show a moderating effect of fatherhood on the association between relationship satisfaction and infidelity. In other words, the effect of relationship satisfaction on infidelity depends on if the participant was a father. More specifically, only in non-fathers was lower relationship satisfaction associated with increased infidelity. This effect can be interpreted according to the mate switching hypothesis, which suggests that non-fathers engage less in extradyadic sexual activities as long as the relationship is perceived as satisfying, while more quickly seeking a new partner in the face of relationship dissatisfaction [19]. This strategy is less appealing to fathers, since changing partners would require a great deal of adaptation with regard to the children involved. Therefore, the link between relationship satisfaction and infidelity among fathers seems to dissolve. Many parent couples come to the point to ask themselves whether it is better to stay in an unsatisfying and conflictual relation for the sake of the children or to separate [68]. And because there is no definite answer to this question, many parents decide to stay in the relationship and within this framework to satisfy their needs as good as possible, which in fathers are also often sexual needs and thus contribute to an increased risk of infidelity [67].

Additionally, the results revealed a discrepancy between directly and indirectly reported infidelity, which was particularly apparent among the fathers. According to the indirect questioning, significantly more fathers had engaged in extradyadic sexual activities than non-fathers (36.6% vs. 21.8%). The reported rates of infidelity are in line with the literature. For instance, Allen et al. [72] reported that around a quarter of married men have engaged in infidelity, with this rate rising to almost 50% in dating relationships [73]. The findings are also consistent with a more recent study from Germany, in which heterosexual men reported infidelity rates of 49% [12]. As most of the participants in this study were married, a rate of just over 30% was seen as representative for the investigated population of Swiss men.

Age and length of relation were positively correlated with infidelity. As the majority of the participants had been married or in a relationship for more than one year, with a mean relationship length of 13.6 years, their relationships can be considered as long-term, which has been shown to increases the risk for infidelity [25]. Fathers and non-fathers did not significantly differ with regard to age, and fathers showed significantly longer relationship length (16.5 years vs. 10.2 years). This was likely contributed to the identified group difference with regard to infidelity. From an evolutionary perspective, higher infidelity rates in longer relationships or older age might be interpreted as a form of ensuring the passing on of genes to as many partners as possible and thus increasing evolutionary fitness. Within the evolutionary psychology framework, another interpretation may be provided by the sexual strategies theory [74], according to which men (and women) follow distinct strategies for short- and long-term sexual relationships, which have evolved during an evolutionary process. Both sexes face different adaptive problems, which they try to solve by weighing up costs and benefits adapted to the needs of the respective situation, i.e., short- or long-term sexual mating. For instance, distress promotes more short-term mating strategies. In contrast to the evolutionary perspective, dissatisfaction and neglect are covariates of sexual motivation for infidelity [75], which might become significantly more important in early fatherhood due to the fact that a couple might experience a shift in lifestyle and responsibilities.

Taken together, we explain the observed findings in such a way that fathers show a substantially reduced relationship satisfaction during the early phases of paternity (e.g., first seven years) and, at the same time, show an increased risk of infidelity. However, since most couples do not want to separate because of their children, this difficult time is eventually overcome followed by an increase in relationship quality and satisfaction. In addition, by raising the children as a couple, one is proud and stronger connected with each other, further leading to increased relationship satisfaction in later phases. Therefore, it will be important for future research to concomitantly map the temporal dynamics of the likelihood of infidelity [34,35] and relationship satisfaction [63,70] over the course of transitioning to parents and raising children to adulthood.

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

The current study had several distinct limitations and strengths. First, infidelity was only assessed with the question of engagement in extradyadic sexual activities, without defining the exact boundaries of “sexual activities”; thus, it was left to the participants’ interpretation how sexual activities are defined. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that the subjective perception of the committing partner is crucial in terms of effects on relationship satisfaction and well-being. However, infidelity was also examined in an indirect way, and thus anonymously, which enabled us to control for social desirability. Furthermore, the question about infidelity did not ask whether infidelity occurred before or exactly when after the birth of the child, and also did not ask about the exact number of incidents or the amount of extradyadic sexual partners. Thus, future research needs to address this issue and capture as precise as possible the time of the extradyadic sexual activity. Another shortcoming of the study is the lack of information about the age of the children, although the number of children was assessed and added as a covariate the age of the oldest child is particularly relevant to identify the period of increased relationship strain due to the first newborn and the period when relationship satisfaction starts to increase again.

Despite these limitations, the study also had several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly focus on the topic of fatherhood, infidelity, and relationship satisfaction. Moreover, we investigated a rather large sample of 253 men, and used validated questionnaires and measurements that enables us to control for possible confounding variables. The questionnaires enabled us to specifically target potentially influencing personality traits and aspects of mental health as covariates. The relatively large sample size allowed for the generalization of the results. Finally, the study investigated indirect effects, which can be regarded as strengths, since infidelity is a complex behavior encompassing multiple aspects. Thus, the measurement of indirect effects enables deeper insights into mechanisms and is more appropriate due to the consideration of the complexity of the behavior.

4.2. Implications

This investigation extended the knowledge about infidelity, especially for fathers. Couples confronted with infidelity experience severe distress. The discovery of infidelity is a critical life event and can cause PTSD-like symptoms with increased anxiety or depression [12,44]. Therefore, it is crucial to provide information about this topic within couples’ therapy. In particular, fathers or expectant fathers and their partners should be educated about relationship changes within fatherhood and the distress this might cause, in order to adequately prepare the expectant parents and prevent infidelity.

5. Conclusions

This study provides first evidence for an association between fatherhood and infidelity, which broadens the understanding of infidelity itself. Despite higher relationship satisfaction, fathers engaged in significantly more extradyadic sexual activities than non-fathers. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution since previous literature did not identify an association between parenthood or the number of children and infidelity. It is further important to consider the temporal dynamics of the risk for infidelity and relationship satisfaction over a life, while the underlying mechanisms of infidelity require further investigation. The importance of the reported findings, especially for families, adds to the novelty of the results and gives rise to opportunities to develop prevention strategies for infidelity or to increase the understanding of and coping with infidelity. Further research might investigate specific age groups of men or types of infidelity in greater detail. Moreover, future studies could employ longitudinal approaches to enable a more detailed investigation and allow for causal inferences to be drawn regarding the associations between infidelity and fatherhood. The dynamic relationship between fatherhood, relationship satisfaction, and infidelity is of major importance for the well-being of all family members. Knowledge of the determinants of infidelity, and providing couples with information might prevent infidelity and subsequent break-up or divorce in many cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J.L., A.W., P.W. and U.E.; methodology, T.J.L.; formal analysis, T.J.L.; investigation, T.J.L., A.W.; resources, U.E.; data curation, A.W., P.W., T.J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J.L.; writing—review and editing, A.W., P.W., U.E.; visualization, T.J.L., A.W.; supervision, U.E.; project administration, T.J.L.; funding acquisition, U.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University Research Priority Program (URPP) “Dynamics of Healthy Aging” of the University of Zurich and by the Jacobs Foundation (2013-1049). The funders played no role in the design, execution, analysis, or interpretation of the current study. The APC was funded by the Publication Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Zurich.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for their participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Conley, T.D.; Moors, A.C.; Matsick, J.L.; Ziegler, A. The fewer the merrier?: Assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2013, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dush, C.M.K.; Amato, P.R. Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2005, 22, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, T.D.; Ziegler, A.; Moors, A.C.; Matsick, J.L.; Valentine, B. A Critical Examination of Popular Assumptions About the Benefits and Outcomes of Monogamous Relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 17, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plack, K.; Kröger, C.; Hahlweg, K.; Klann, N. Außerpartnerschaftliche beziehungen—Die individuelle belastung der partner und die partnerschaftliche zufriedenheit nach dem erleben von untreue kurzbericht. Z. Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 2008, 37, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøntvedt, T.V.; Kennair, L.E.O.; Bendixen, M. How Intercourse Frequency is Affected by Relationship Length, Relationship Quality, and Sexual Strategies Using Couple Data. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.B.; Rhoades, G.K.; Stanley, S.M.; Allen, E.S.; Markman, H.J. Reasons for Divorce and Recollections of Premarital Intervention: Implications for Improving Relationship Education. Couple Fam. Psychol. 2013, 2, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.R.; Previti, D. People’s reasons for divorcing gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. J. Fam. Issues 2003, 24, 602–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaris, A. Burning the Candle at Both Ends: Extramarital Sex as a Precursor of Marital Disruption. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 1474–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blow, A.J.; Hartnett, K. Infidelity in Committed Relationships I: A Methodological Review. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2005, 31, 183–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Pereira, M.; Andrade, R.; Dattilio, F.M.; Narciso, I.; Cristina, M. Infidelity in Dating Relationships: Gender-Specific Correlates of Face-to-Face and Online Extradyadic Involvement. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, R.J.; Markey, C.M.; Mills, A.; Hodges, S.D. Sex Differences in Self-reported Infidelity and its Correlates. Sex Roles 2007, 57, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haversath, J.; Kröger, C. Sexuelle Auβenkontakte und deren Prädiktoren bei Homo- und Heterosexuellen. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2014, 64, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, C. Sexuelle Außenkontakte und -beziehungen in heterosexuellen Partnerschaften. Psychol. Rundsch. 2010, 61, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studienreihe, J.K. Trendcheck: Verlieben. Available online: https://docplayer.org/57703923-Trendcheck-verlieben.html (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Rusbult, C.E. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 16, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Johnson, D.J.; Morrow, G.D. Predicting satisfaction and commitment in adult romantic involvements: An assessment of the generalizability of the investment model. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1986, 49, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, A. Marital infidelity. Society 1994, 31, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, S.; Veldorale-Brogan, A.; Kimber, S.B.; Fincham, F.D. Predictors of extradyadic sex among young adults in heterosexual dating relationships: A multivariate approach. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 34, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M.; Goetz, C.; Duntley, J.D.; Asao, K.; Conroy-Beam, D. The mate switching hypothesis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilski, J.K.; Memering, S.L.; Welling, L.L.M.; Shackelford, T.K. Monogamy versus Consensual Non-Monogamy: Alternative Approaches to Pursuing a Strategically Pluralistic Mating Strategy. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, M.; Millar, M.; Westfall, R.S. Sex Differences in Responses to Emotional and Sexual Infidelity in Dating Relationships. J. Individ. Differ. 2019, 40, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitty, M.T. Emotional and Sexual Infidelity Offline and in Cyberspace. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2008, 34, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, R. Parents’ convergence on sharing and marital satisfaction, father involvement, and parent–child relationship at the transition to parenthood. Infant Ment. Health J. Off. Publ. World Assoc. Infant Ment. Health 2000, 21, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldvogel, P.; Ehlert, U. Contemporary Fatherhood and Its Consequences for Paternal Psychological Well-being—A Cross-sectional Study of Fathers in Central Europe. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, B.L.; Niles, R.L.; Tatcher, A.M. Sources of Marital Dissatisfaction Among Newly Separated Persons. J. Fam. Issues 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, C.F.; Duncan, G.; Rutsohn, J.; McDade, T.W.; Adam, E.K.; Coley, R.L.; Chase-Lansdale, P.L. A Longitudinal Study of Paternal Mental Health During Transition to Fatherhood as Young Adults. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, T.; Ditzen, B.; Fischbacher, S.; Ehlert, U. Testosterone and relationship quality across the transition to fatherhood. Biol. Psychol. 2012, 90, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Milkie, M.A.; Journal, S.; May, N. Costs and Rewards of Children: The Effects of Becoming a Parent on Adults’ Lives. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.H.; Fincham, F.D. Psychological Distress: Precursor or Consequence of Dating Infidelity? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp Dush, C.M.; Rhoades, G.K.; Sandberg-Thoma, S.E.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J. Commitment across the transition to parenthood among married and cohabiting couples. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2014, 3, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox Shaw, A.M.; Rhoades, G.K.; Allen, E.S.; Stanley, S.M.; Markman, H.J. Predictors of Extradyadic Sexual Involvement in Unmarried Opposite-Sex Relationships. J. Sex. Res. 2013, 50, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, B. Extramarital sex in the Netherlands—Motivations in social and marital context. Altern. Lifestyles 1980, 3, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.N.; Booth, A. Sexual behavior in and out of marriage: An assessment of correlates. J. Marriage Fam. 1976, 38, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. A theory of marital sexual life. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederman, M.W. Extramarital Sex: Prevalence and Correlates in a National Survey. J. Sex. Res. 1997, 34, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A.; Ehlert, U. Steroid secretion and psychological well-being in men 40+. In Neurobiology of Men’s Mental Health; Rice, T.R., Sher, L., Eds.; Nova: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 287–322. ISBN 9780578058498. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, A.; Mahler, F.; Debelak, R.; Ehlert, U. Psychobiological Protective Factors Modifying the Association Between Age and Sexual Health in Men: Findings From the Men’ s Health 40 + Study. Am. J. Mens Health 2017, 11, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiacco, S.; Walther, A.; Ehlert, U. Steroid secretion in healthy aging. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 105, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkin, M.J. Sexual health and relationships after age 60. Maturitas 2016, 83, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, A.; Grace, V.; Gavey, N.; Vares, T. “Viagra stories”: Challenging ‘erectile dysfunction’. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A.; Breidenstein, J.; Miller, R. Association of testosterone treatment with alleviation of depressive symptoms in men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A.; Seuffert, J. Testosterone and Dehydroepiandrosterone Treatment in Ageing Men: Are We All Set? World J. Mens. Health 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.R. The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 1269–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, F.D.; May, R.W. Infidelity in romantic relationships. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.P. The big five related to risky sexual behaviour across 10 world regions: Differential personality associations of sexual promiscuity and relationship infidelity. Eur. J. Pers. 2004, 18, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTernan, M.; Love, P.; Rettinger, D. The Influence of Personality on the Decision to Cheat. Ethics Behav. 2014, 24, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.M.; Negash, S.; Lambert, N.M.; Fincham, F.D. Problem Drinking and Extradyadic Sex in Young Adult Romantic Relationships. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penke, L.; Asendorpf, J.B. Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seal, D.W.; Agostinelli, G.; Hannett, C.A. Extradyadic romantic involvement: Moderating effects of sociosexuality and gender. Sex Roles 1994, 31, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treas, J.; Giesen, D. Sexual Infidelity Among Married and Cohabiting Americans. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, C.; Ehlert, U.; Lacker, T.J.; Waldvogel, P.; Walther, A. Higher testosterone levels are associated with unfaithful behavior in men. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, D.A.; Weigel, D.J.; Lalasz, C.B.; Evans, W.P. Family Background and Propensity to Engage in Infidelity. J. Fam. Issues 2015, 38, 2083–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.B. The third wheel: The impact of Twitter use on relationship infidelity and divorce. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, D.C.; Baucom, D.H.; Jacobson, N.S. Understanding Infidelity: Correlates in a National Random Sample. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001, 15, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, A.; Phillip, M.; Lozza, N.; Ehlert, U. The rate of change in declining steroid hormones: A new parameter of healthy aging in men? Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.; Böcker, S. Die Deutsche Form der Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS): Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der Zufriedenheit in einer Partnerschaft. Diagnostica 1993, 39, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jann, B.; Jerke, J.; Krumpal, I. Asking sensitive questions using the crosswise model: An experimental survey measuring plagiarism. Public Opin. Q. 2012, 76, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory (BFI-K): Entwicklung und validierung eines ökonomischen inventars zur erfassung der fünf faktoren der persönlichkeit. Diagnostica 2005, 51, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabora, J.; Brintzenhofeszoc, K.; Jacobsen, P.; Curbow, B.; Piantadosi, S.; Hooker, C.; Owens, A.; Derogatis, L. A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics 2001, 42, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. 2012. Available online: https://docplayer.net/20816210-Process-a-versatile-computational-tool-for-observed-variable-mediation-moderation-and-conditional-process-modeling-1.html (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Hendricks, M.L., Testa, R.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 43, p. 460467. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Robinson, B.; Cohn, A.; Gildenblatt, L.; Barkley, S. The Possible Trajectory of Relationship Satisfaction Across the Longevity of a Romantic Partnership: Is There a Golden Age of Parenting? Fam. J. 2016, 24, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Psychogiou, L.; Kuyken, W.; Ford, T.; Ryan, E.; Russell, G. The prevalence of depressive symptoms among fathers and associated risk factors during the first seven years of their child’s life: Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, O.; Nguyen, T.; Thomas, N.; Thomson-Salo, F.; Handrinos, D.; Judd, F. Perinatal mental health: Fathers—The (mostly) forgotten parent. Asia Pacific Psychiatry 2016, 8, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfitt, Y.; Ayers, S. Transition to parenthood and mental health in first-time parents. Infant Ment. Health J. 2014, 35, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, N.O.; Bailey, K.; Muise, A. Degree and Direction of Sexual Desire Discrepancy are Linked to Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction in Couples Transitioning to Parenthood. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, E.M. Should we stay together for the sake of the children. In Coping with Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage: A Risk and Resiliency Perspective; Hetherington, E.M., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- La Taillade, J.J.; Hofferth, S.; Wight, V.R. Consequences of fatherhood for young men’s relationships with partners and parents. Res. Hum. Dev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keizer, R.; Schenk, N. Becoming a parent and relationship satisfaction: A longitudinal dyadic perspective. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selterman, D.; Garcia, J.R.; Tsapelas, I. Motivations for Extradyadic Infidelity Revisited. J. Sex Res. 2017, 56, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.S.; Atkins, D.C.; Baucom, D.H.; Snyder, D.K.; Gordon, K.C.; Glass, S.P. Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Contextual Factors in Engaging in and Responding to Extramarital Involvement. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2005, 12, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederman, M.W.; Hurd, C. Extradyadic Involvement during Dating. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1999, 16, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, D.M.; Schmitt, D.P. Sexual Strategies Theory: An Evolutionary Perspective on Human Mating. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 204–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, W.D.; Kiene, S.M. Motivations for infidelity in heterosexual dating couples: The roles of gender, personality differences, and sociosexual orientation. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2005, 22, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).