A Lightweight LLM-Based Semantic–Spatial Inference Framework for Fine-Grained Urban POI Analysis

Highlights

- A fine-tuned open large language model (Qwen3-8B + LoRA) achieves superior fine-grained classification of unstructured POI texts (macro-F1 = 0.843), outperforming BERT and commercial LLM baselines while running on consumer-grade hardware.

- The framework expands usable fine-category POI labels by ≈14–15× in Guangzhou and Shenzhen, enabling robust 500 m grid residual–hotspot analyses that reveal structural cultural preferences and urban diversity patterns.

- The pipeline transforms unstructured urban text into interpretable spatial evidence, providing a reproducible and resource-efficient method for service-equity assessment and cultural-space analysis in planning.

- Its domain-agnostic, lightweight design can be extended to other urban functions (e.g., healthcare, education), offering a scalable tool for fine-resolution spatial governance in smart-city contexts.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Framework

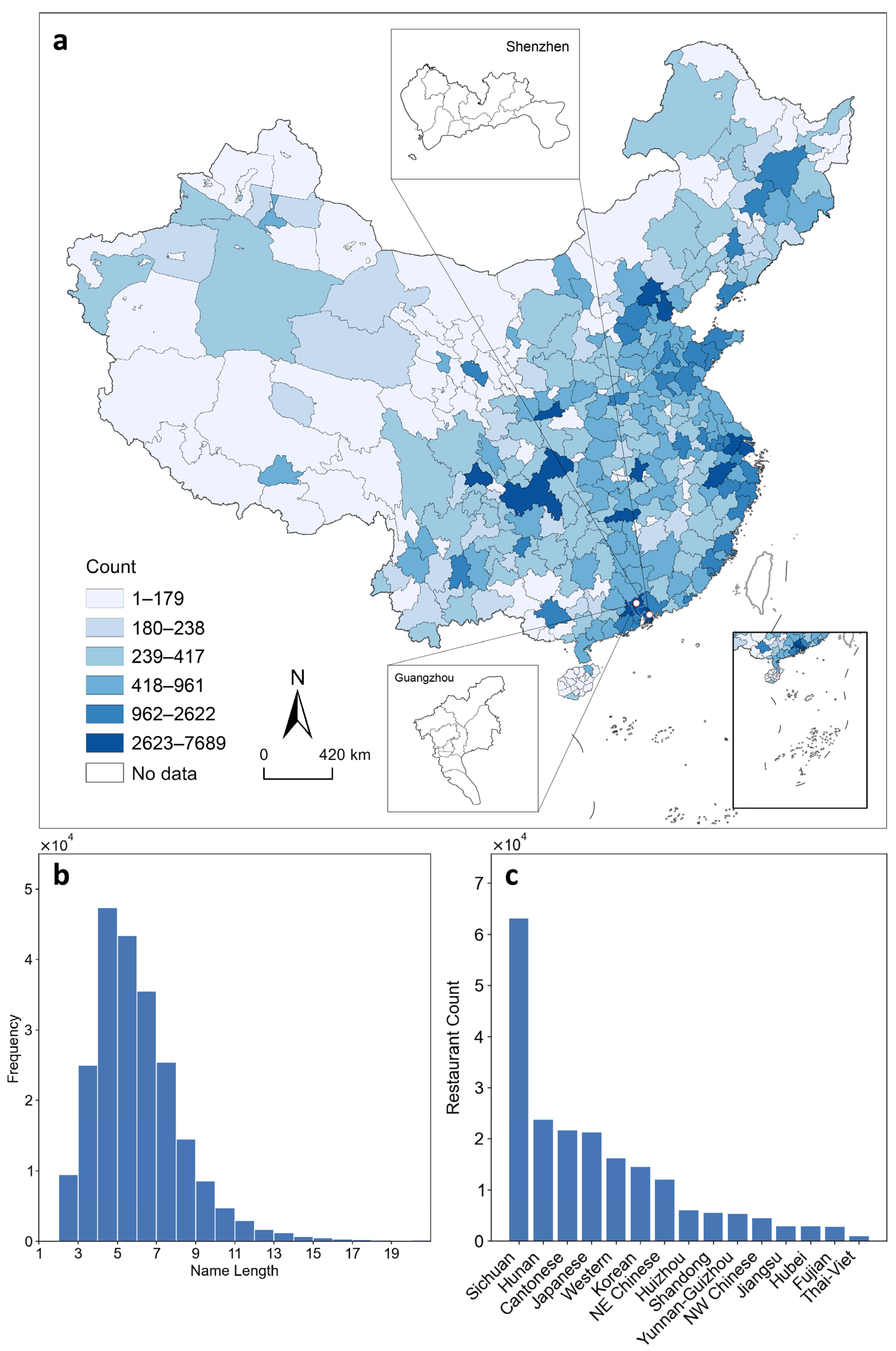

2.2. Data and Preprocessing

2.3. Model and Lightweight Fine-Tuning

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

2.5. Residuals and Spatial Analysis

2.6. Key Methodological Assumptions

3. Results

3.1. Overall Classification Performance

3.2. Per-Class Performance

3.3. Confusion Analysis

4. Case Study: Guangzhou and Shenzhen

4.1. Data Expansion and Classification Scaling

4.2. City-Level Composition and Spatial Patterns

4.3. Cultural Embedding Through Hotspot and Residual Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| Gi* | Getis–Ord Gi* statistic |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LLM-SSIF | LLM-based semantic–spatial inference framework |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PEFT | Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning |

| POI | Point of Interest |

| SFT | Supervised Fine-Tuning |

| VCR | Valid Coverage Rate |

Appendix A. Cross-Regional Urban Case Study: Chengdu

Appendix A.1. Motivation and Case Selection

Appendix A.2. Label Expansion and Overall Cuisine Structure

| Cuisine Name | Label Count | LLM Count | Lift Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| NE Chinese | 65 | 1478 | 22.74 |

| Yunnan–Guizhou | 54 | 1359 | 25.17 |

| Sichuan | 3647 | 84,808 | 23.25 |

| Huizhou | 3 | 95 | 31.67 |

| Japanese | 504 | 1784 | 3.54 |

| Thai–Viet | 40 | 139 | 3.48 |

| Hunan | 37 | 538 | 14.54 |

| Cantonese | 176 | 5569 | 31.64 |

| Jiangsu | 9 | 53 | 5.89 |

| NW Chinese | 95 | 1592 | 16.76 |

| Western | 353 | 11,298 | 32.01 |

| Hubei | 6 | 86 | 14.33 |

| Fujian | 22 | 384 | 17.45 |

| Korean | 264 | 2241 | 8.49 |

| Shandong | 5 | 195 | 39.00 |

| Total | 5280 | 111,619 | 21.14 |

Appendix A.3. Grid-Level Distribution of Restaurant Density

Appendix A.4. Cultural Embedding Through Hotspot and Residual Analysis

Appendix A.5. Summary of the Chengdu Case

References

- Milias, V.; Psyllidis, A. Assessing the Influence of Point-of-Interest Features on the Classification of Place Categories. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 86, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, T.; Law, S.; Zeng, Z.; Yin, L.; Liu, J. Multi-Modal Contrastive Learning of Urban Space Representations from POI Data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2025, 120, 102299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Bo, S.; Wang, J. Classifying Urban Functional Zones by Integrating the Homogeneity and Structural Similarity of POIs. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 04024052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.; Alves, A.; Bento, C. POI Mining for Land Use Classification: A Case Study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Alves, A.; Rodrigues, F.; Ferreira, J.; Pereira, F.C. Mining Point-of-Interest Data from Social Networks for Urban Land Use Classification and Disaggregation. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 53, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Ratti, C.; Zheng, S. Predicting Neighborhoods’ Socioeconomic Attributes Using Restaurant Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 15447–15452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kuai, C.; Liao, X.; Ma, H.; He, B.Y.; Ma, J. Semantic Trajectory Data Mining with LLM-Informed POI Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024; pp. 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, W.; Bai, X.; Shi, Y.; Han, Y.; Peng, Z.-R.; Gu, C. Beyond Word2vec: An Approach for Urban Functional Region Extraction and Identification by Combining Place2vec and POIs. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; He, Z.; Wu, L.; Yin, L.; Xu, Y.; Cui, H. A Framework for Extracting Urban Functional Regions Based on Multiprototype Word Embeddings Using Points-of-Interest Data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 80, 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Silva, E.A. Delineating Urban Functional Use from Points of Interest Data with Neural Network Embedding: A Case Study in Greater London. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 88, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Janowicz, K.; Mai, G.; Gao, S. From ITDL to Place2Vec: Reasoning About Place Type Similarity and Relatedness by Learning Embeddings from Augmented Spatial Contexts. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Redondo Beach, CA, USA, 7–10 November 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Yin, L.; Lu, F.; Mou, N. Visualizing and Exploring POI Configurations of Urban Regions on POI-Type Semantic Space. Cities 2020, 99, 102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Du, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yang, R. A Semantically Enhanced Label Prediction Method for Imbalanced POI Data Category Distribution. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chen, J.; Wei, C. A Hierarchical Learning Model for Inferring the Labels of Points of Interest with Unbalanced Data Distribution. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 108, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, L.W.; Low, R.; Tan, Y.X.; Cheah, L.; Yeow, L.W.; Low, R.; Tan, Y.X.; Cheah, L. Point-of-Interest (POI) Data Validation Methods: An Urban Case Study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Chakeri, A.; Krim, H. Discovering Urban Functional Zones from Biased and Sparse Points of Interests and Sparse Human Activities. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 207, 118062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amap POI Classification Table. Available online: https://lbs.amap.com/api/webservice/download (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Baidu POI Classification System. Available online: https://lbsyun.baidu.com/index.php?title=open/poitags (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Sun, K.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, R.Z.; Zhu, Y. Conflating Point of Interest (POI) Data: A Systematic Review of Matching Methods. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 103, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Zhong, T.; Hui, B.; Zhou, F.; Trajcevski, G. Spatial-Temporal Contrasting for Fine-Grained Urban Flow Inference. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2023, 9, 1711–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xia, C. The Effects of Sample Size and Sample Prevalence on Cellular Automata Simulation of Urban Growth. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 158–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. POI GPT: Extracting POI Information from Social Media Text Data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-4/W10-2024, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xia, L.; Ren, X.; Tang, J.; Chen, T.; Xu, Y.; Huang, C. Urban Computing in the Era of Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2025, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, F.; Lin, Y.; Santi, P.; Ratti, C.; Wang, Q.R.; Li, Y. Urban Planning in the Era of Large Language Models. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2025, 5, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carammia, M.; Iacus, S.M.; Porro, G. Rethinking Scale: The Efficacy of Fine-Tuned Open-Source LLMs in Large-Scale Reproducible Social Science Research. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.00890. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; He, Z.; Guan, Q.; Lin, J.; Yu, W. Geospatial Large Language Model Trained with a Simulated Environment for Generating Tool-Use Chains Autonomously. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 136, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryan, A.; Nain, A.K.; McMahon, A.; Meyer, L.A.; Sahota, H.S. The Costly Dilemma: Generalization, Evaluation and Cost-Optimal Deployment of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.08061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Kubli, M.; Samei, Z.; Dehghani, S.; Zahedivafa, M.; Bermeo, J.D.; Korobeynikova, M.; Gilardi, F. Open-Source LLMs for Text Annotation: A Practical Guide for Model Setting and Fine-Tuning. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Luo, Z.; Feng, Z.; Ma, Y. LlamaFactory: Unified Efficient Fine-Tuning of 100+ Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.13372. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09685. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, N.; Qin, Y.; Yang, G.; Wei, F.; Yang, Z.; Su, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chan, C.-M.; Chen, W.; et al. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning of Large-Scale Pre-Trained Language Models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Turner, R.; Møller, J.; Hazelton, M. Residual Analysis for Spatial Point Processes (with Discussion). J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. Stat. Methodol. 2005, 67, 617–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reades, J.; Hu, Y.; Tranos, E.; Delmelle, E. The City as Text. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X. POI-Enhancer: An LLM-Based Semantic Enhancement Framework for POI Representation Learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 11509–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Tang, G. Using Restaurant POI Data to Explore Regional Structure of Food Culture Based on Cuisine Preference. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S.; Song, M.; Jin, L.; Jiang, W.; Wang, X.; Ning, W.; Yu, S.; Xuan, Q.; et al. FashionGPT: LLM Instruction Fine-Tuning with Multiple LoRA-Adapter Fusion. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 299, 112043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathav Raj, J.; Kushala, V.; Warrier, H.; Gupta, Y. Fine Tuning LLM for Enterprise: Practical Guidelines and Recommendations. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.10779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall Plot Is More Informative than the ROC Plot When Evaluating Binary Classifiers on Imbalanced Datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadpour, S.; Warner, T.A.; Maxwell, A.E. Selecting and Interpreting Multiclass Loss and Accuracy Assessment Metrics for Classifications with Class Imbalance: Guidance and Best Practices. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Tong, X. Imbalanced Classification: A Paradigm-Based Review. Stat. Anal. Data Min. ASA Data Sci. J. 2021, 14, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, J. A Closer Look at Classification Evaluation Metrics and a Critical Reflection of Common Evaluation Practice. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 12, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.H.; Montgomery, D.C. A Tutorial on Generalized Linear Models. J. Qual. Technol. 1997, 29, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Abid, W.; Angus, G.; Garg, A.; Kinnison, J.; Sherstinsky, A.; Molino, P.; Addair, T.; Rishi, D. LoRA Land: 310 Fine-Tuned LLMs That Rival GPT-4, A Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.00732. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K.; Ghani, A.; Alzahrani, A.; Tariq, M.U.; Rahman, A.U. Pre-Trained Model-Based NFR Classification: Overcoming Limited Data Challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81787–81802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Grunwald, A.; Saha, S. Access to Cultural Ecosystem Services and How Urban Green Spaces Marginalize Underprivileged Groups. npj Urban Sustain. 2025, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, M.; Lovsjö, N.; Keuschnigg, M. Urban Scaling Laws Arise from Within-City Inequalities. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, K.; Song, C.; Yin, Y. Understanding the Regional Dynamics and Determinants of Urban Cultural Facilities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, C.; Marjavaara, R. Airbnb and Urban Population Change: An Empirical Analysis of the Case of Stockholm, Sweden. Urban Res. Pract. 2024, 17, 654–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Cuisine Name | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Northeastern Chinese Cuisine | NE Chinese | Hearty dishes, wheat-based staples |

| 2 | Yunnan–Guizhou Cuisine | Yunnan–Guizhou | Spicy, sour, ethnic minority flavors |

| 3 | Sichuan Cuisine | Sichuan | Famous for chili, numbing spices |

| 4 | Huizhou Cuisine | Huizhou | Anhui region, stews, umami flavors |

| 5 | Japanese Cuisine | Japanese | Sushi, ramen, seafood |

| 6 | Thai–Vietnamese Cuisine | Thai–Viet | Spicy, sour, fresh herbs |

| 7 | Hunan Cuisine | Hunan | Hot, sour, bold flavors |

| 8 | Cantonese Cuisine | Cantonese | Dim sum, mild seasoning, seafood |

| 9 | Jiangsu Cuisine | Jiangsu | Freshwater fish, light sweet taste |

| 10 | Northwestern Chinese Cuisine | NW Chinese | Lamb, wheaten foods, hearty flavors |

| 11 | Western Cuisine | Western | European and American styles, grilled meats, dairy |

| 12 | Hubei Cuisine | Hubei | Freshwater fish, noodles |

| 13 | Fujian Cuisine | Fujian | Seafood, soups, mild sweetness |

| 14 | Korean Cuisine | Korean | Kimchi, barbecue, rice dishes |

| 15 | Shandong Cuisine | Shandong | Seafood, wheat, light salty flavors |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | Qwen3-8B |

| Fine-tuning method | LoRA |

| LoRA rank (r) | 8 |

| LoRA α | 16 |

| LoRA dropout | 0 |

| LoRA target | All attention modules |

| Trainable parameters | 21,823,488 (≈0.27% of 8.21B backbone) |

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning rate | 5 × 10−5 |

| Scheduler | Cosine decay |

| Precision | bfloat16 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Max sequence length | 512 tokens |

| Epochs | max 10 (early stopping at ~4.66) |

| Training duration (wall-clock) | ~13.25 h |

| Dataset split | Train:Val:Test = 64%:16%:20% |

| City | Cuisine | Moran’s I (Raw) | Moran’s I (Residual) | ΔI (Residual—Raw) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangzhou | Cantonese | 0.2471 | 0.0615 | −0.1856 |

| Hunan | 0.1255 | 0.0848 | −0.0407 | |

| Western | 0.2405 | 0.0187 | −0.2218 | |

| Shenzhen | Cantonese | 0.1174 | 0.0862 | −0.0312 |

| Hunan | 0.1020 | 0.0943 | −0.0077 | |

| Western | 0.1885 | 0.0177 | −0.1708 |

| Model | Qwen3-8B PEFT (LoRA) | GPT-4o | Doubao-1.5-Pro | DeepSeek-R1 | BERT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.893 | 0.861 | 0.875 | 0.881 | 0.817 |

| Precision | 0.835 | 0.777 | 0.777 | 0.790 | 0.753 |

| Recall | 0.853 | 0.838 | 0.880 | 0.887 | 0.678 |

| F1-score | 0.843 | 0.801 | 0.813 | 0.827 | 0.704 |

| VCR (%) | 95.82% | 90.80% | 86.90% | 90.54% | 97.02% |

| Cuisine Name | Qwen3-8B PEFT (LoRA) | GPT-4o | Doubao-1.5-Pro | DeepSeek-R1 | BERT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE Chinese | 0.884 | 0.786 | 0.866 | 0.834 | 0.798 |

| Yunnan–Guizhou | 0.830 | 0.745 | 0.830 | 0.800 | 0.672 |

| Sichuan | 0.920 | 0.902 | 0.915 | 0.913 | 0.856 |

| Huizhou | 0.908 | 0.838 | 0.846 | 0.900 | 0.625 |

| Japanese | 0.931 | 0.935 | 0.941 | 0.939 | 0.918 |

| Thai–Viet | 0.824 | 0.825 | 0.801 | 0.848 | 0.825 |

| Hunan | 0.899 | 0.885 | 0.899 | 0.904 | 0.815 |

| Cantonese | 0.880 | 0.840 | 0.855 | 0.885 | 0.790 |

| Jiangsu | 0.659 | 0.618 | 0.570 | 0.644 | 0.299 |

| NW Chinese | 0.800 | 0.736 | 0.722 | 0.690 | 0.778 |

| Western | 0.885 | 0.871 | 0.891 | 0.888 | 0.867 |

| Hubei | 0.751 | 0.747 | 0.714 | 0.774 | 0.362 |

| Fujian | 0.732 | 0.640 | 0.616 | 0.661 | 0.555 |

| Korean | 0.916 | 0.904 | 0.914 | 0.915 | 0.913 |

| Shandong | 0.832 | 0.745 | 0.809 | 0.812 | 0.484 |

| Cuisine Name | Guangzhou | Shenzhen | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label Count | LLM Count | Lift Ratio | Label Count | LLM Count | Lift Ratio | |

| NE Chinese | 105 | 1811 | 17.25 | 146 | 2557 | 17.51 |

| Yunnan–Guizhou | 30 | 718 | 23.93 | 38 | 876 | 23.05 |

| Sichuan | 879 | 9437 | 10.74 | 1145 | 13,381 | 11.69 |

| Huizhou | 6 | 91 | 15.17 | 14 | 143 | 10.21 |

| Japanese | 611 | 3024 | 4.95 | 493 | 2562 | 5.20 |

| Thai–Viet | 46 | 203 | 4.41 | 30 | 132 | 4.40 |

| Hunan | 1213 | 5843 | 4.82 | 1784 | 9926 | 5.56 |

| Cantonese | 2203 | 45,267 | 20.55 | 2084 | 38,162 | 18.31 |

| Jiangsu | 3 | 61 | 20.33 | 8 | 91 | 11.38 |

| NW Chinese | 72 | 1824 | 25.33 | 123 | 2698 | 21.93 |

| Western | 476 | 14,926 | 31.36 | 359 | 12,983 | 36.16 |

| Hubei | 50 | 906 | 18.12 | 87 | 1372 | 15.77 |

| Fujian | 46 | 1900 | 41.30 | 69 | 2331 | 33.78 |

| Korean | 202 | 2341 | 11.59 | 169 | 2959 | 17.51 |

| Shandong | 7 | 213 | 30.43 | 13 | 366 | 28.15 |

| Total | 5949 | 88,565 | 14.89 | 6562 | 90,539 | 13.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhao, M. A Lightweight LLM-Based Semantic–Spatial Inference Framework for Fine-Grained Urban POI Analysis. Smart Cities 2026, 9, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010013

Huang Z, Guo Y, Huang S, Zhao M. A Lightweight LLM-Based Semantic–Spatial Inference Framework for Fine-Grained Urban POI Analysis. Smart Cities. 2026; 9(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Zhuo, Yixing Guo, Shuo Huang, and Miaoxi Zhao. 2026. "A Lightweight LLM-Based Semantic–Spatial Inference Framework for Fine-Grained Urban POI Analysis" Smart Cities 9, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010013

APA StyleHuang, Z., Guo, Y., Huang, S., & Zhao, M. (2026). A Lightweight LLM-Based Semantic–Spatial Inference Framework for Fine-Grained Urban POI Analysis. Smart Cities, 9(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities9010013