The Smart Community: Strategy Layers for a New Sustainable Continental Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Hydrogen Initiative

3.2. The Nuclear Initiative

3.3. The Natural Gas Initiative

3.4. The Renewables Initiative

3.5. The Synthetics and Biomass Initiative

3.6. The ESG Initiative

3.7. The Digital Initiative

3.8. Study Limitation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as regards corporate sustainability reporting

“The NFRD applies to large public-interest entities with an average number of employees in excess of 500, and to public-interest entities that are parent companies of a large group with an average number of employees in excess of 500 on a consolidated basis. 2 The NFRD exempts subsidiaries from its reporting obligations if their parent company does the reporting for the whole group, including the subsidiaries. Approximately 11,700 companies are subject to the reporting requirements of the NFRD 3.”

- 2.

- Corporate sustainability reporting—Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council

“of 22 October 2014, amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups”

- 3.

- The European Green Deal

“The EU is fighting climate change through ambitious policies at home and close cooperation with international partners.”

- 4.

- REPowerEU: affordable, secure and sustainable energy for Europe

“In response to the hardships and global energy market disruption caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Commission presented the REPowerEU Plan.”

- 5.

- Climate action and the Green Deal

“The European Green Deal aims to make Europe climate neutral by 2050.”

- 6.

- Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021

“Establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’)”

- 7.

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions-A new Circular Economy Action Plan For a cleaner and more competitive Europe

“As half of total greenhouse gas emissions and more than 90% of biodiversity loss and water stress come from resource extraction and processing, the European Green Deal launched a concerted strategy for a climate-neutral, resource-efficient and competitive economy. Scaling up the circular economy from front-runners to the mainstream economic players will make a decisive contribution to achieving climate neutrality by 2050 and decoupling economic growth from resource use, while ensuring the long-term competitiveness of the EU and leaving no one behind.”

- 8.

- Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for the setting of ecodesign requirements for energy-related products (recast) (Text with EEA relevance)

“This Directive establishes a framework for the setting of Community ecodesign requirements for energy-related products with the aim of ensuring the free movement of such products within the internal market. ”

“This Directive provides for the setting of requirements which the energy-related products covered by implementing measures must fulfil in order to be placed on the market and/or put into service. It contributes to sustainable development by increasing energy efficiency and the level of protection of the environment, while at the same time increasing the security of the energy supply.”

“This Directive shall not apply to means of transport for persons or goods.”

“This Directive and the implementing measures adopted pursuant thereto shall be without prejudice to Community waste management legislation and Community chemicals legislation, including Community legislation on fluorinated greenhouse gases.”

- 9.

- EU Ecolabel

“The official European Union voluntary label for environmental excellence. Established in 1992 and recognised across Europe and worldwide, the EU Ecolabel certifies products with a guaranteed, independently-verified low environmental impact. To be awarded the EU Ecolabel, goods and services should meet high environmental standards throughout their entire life cycle: from raw material extraction through production and distribution to disposal. The label also encourages companies to develop innovative products that are durable, easy to repair and recyclable.”

- 10.

- Green Public Procurement

“Although GPP is a voluntary instrument, it has a key role to play in the EU’s efforts to become a more resource-efficient economy. It can help stimulate a critical mass of demand for more sustainable goods and services which otherwise would be difficult to get onto the market. GPP is therefore a strong stimulus for eco-innovation.”

- 11.

- Life-cycle costing

“Under the 2014 EU procurement rules a contract must be awarded based on the most economically advantageous tender (MEAT). A number of different approaches are available under this general heading, some of which may be considered appropriate for GPP. Cost or price will form part of the assessment of any procedure, and is usually one of the most influential factors. Costs may be calculated on the basis of a product’s life-cycle. But how do you define the cost?”

“Life-cycle costing (LCC) means considering all the costs that will be incurred during the lifetime of the product, work or service:

- 12.

- Commission Staff Working Document EU—green public procurement criteria for road transport

“EU green public procurement (GPP) criteria are designed to make it easier for public authorities to purchase goods, services and works with reduced environmental impacts. The use of the criteria is voluntary. The criteria are formulated in such a way that they can, if deemed appropriate by the individual authority, be (partially or fully) integrated into the authority’s tender documents with minimal editing. Before publishing a call for tender, public authorities are advised to check the available offer of the goods, services and works they plan to purchase on the market where they are operating. When a contracting authority intends to use the criteria suggested in this document, it shall do so in a manner which ensures compliance with the requirements of EU public procurement legislation (see, for instance, Articles 42, 43, 67(2) or 68 of Directive 2014/24 and similar provisions in other EU public procurement legislation). Practical reflections on this matter is also provided the 2016 handbook on buying green, available at http://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/buying_handbook_en.htm”

- 13.

- Buying green handbook

“The Handbook is the European Commission’s main guidance document to help public authorities buy goods and services with a lower environmental impact. It is also a useful reference for policy makers and companies responding to green tenders.”

- 14.

- European Climate Pact

“Science tells us we have to act urgently to achieve our Paris Agreement goals, notably to limit global warming to well below 2 °C and pursue efforts to limit such warming to 1.5 °C above 1990 levels.

- 15.

- Paris Agreement

“The Paris Agreement sets out a global framework to avoid dangerous climate change by limiting global warming to well below 2 °C and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C. It also aims to strengthen countries’ ability to deal with the impacts of climate change and support them in their efforts.”

- 16.

- Katowice climate package

“On mitigation, the Katowice Climate Package provides guidance for the second round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that countries will submit by 2025. The guidance describes the contents of and approach to mitigation goals and activities to ensure comparability across NDC. The guidelines also address: mitigation co-benefits; capacity-building support to help developing countries produce their NDCs; a common timeframe for communicating NDCs; negative impacts of response measures on certain countries and sectors; and modalities for the operation and use of a public NDC registry.”

- 17.

- Global Climate Action Agenda

“Outside of the formal intergovernmental negotiations, countries, cities and regions, businesses and civil society members across the world are already taking action for the climate.”

- 18.

- Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy—Eastern Europe

“The EU Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy brings together thousands of local governments voluntarily committed to implementing EU climate and energy objectives.”

“The Covenant of Mayors was launched in 2008 in Europe with the ambition to gather local governments voluntarily committed to achieving and exceeding the EU climate and energy targets.”

“Not only did the initiative introduce a first-of-its-kind bottom-up approach to energy and climate action, but its success quickly went beyond expectations.”

“The initiative now gathers 9000+ local and regional authorities across 57 countries drawing on the strengths of a worldwide multi-stakeholder movement and the technical and methodological support offered by dedicated offices.”

- 19.

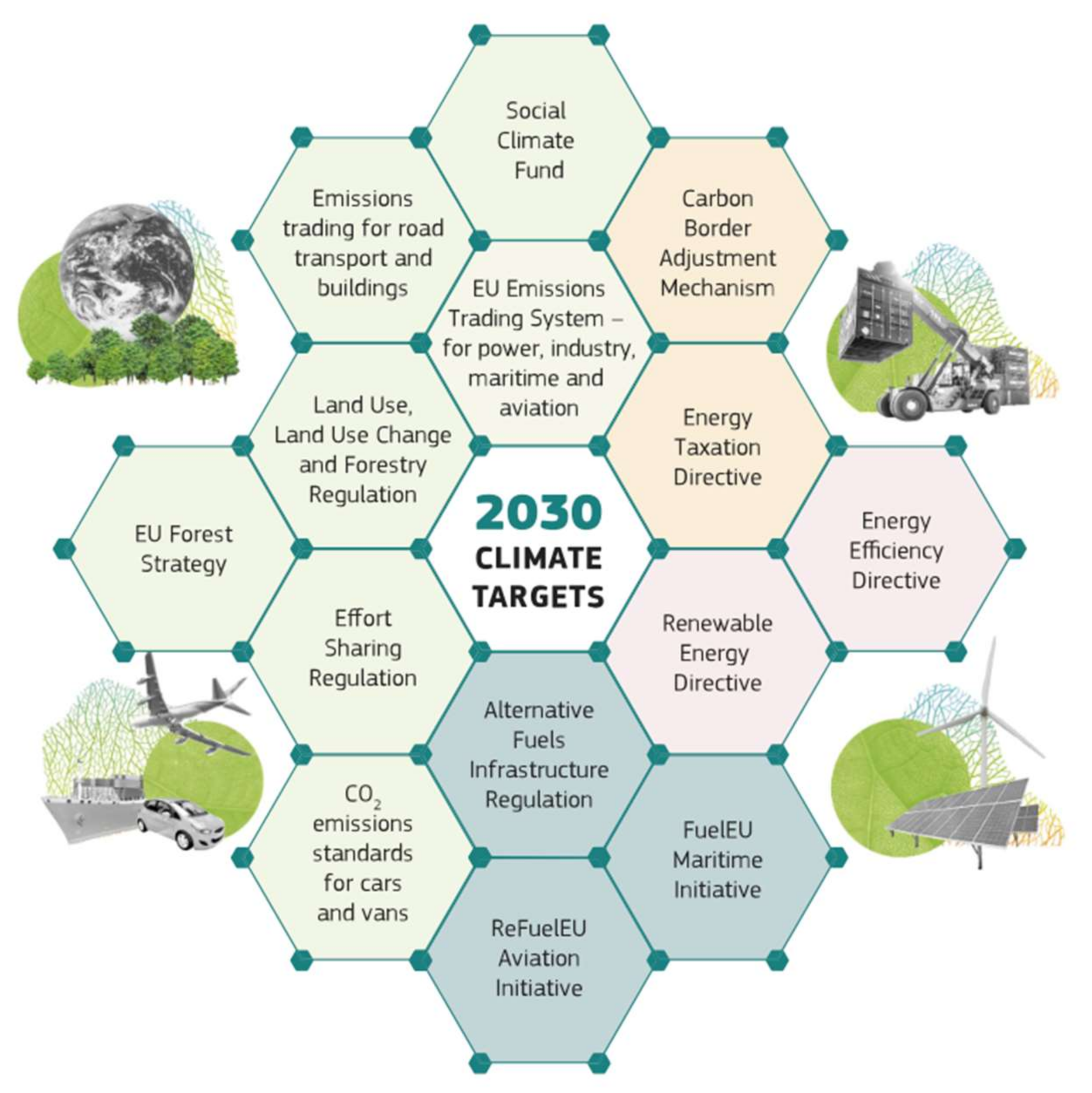

- 2030 Climate Target Plan

“The Commission’s proposal to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 sets Europe on a responsible path to becoming climate neutral by 2050”

“Based on a comprehensive impact assessment, the Commission has proposed to increase the EU’s ambition on reducing greenhouse gases and set this more ambitious path for the next 10 years. The assessment shows how all sectors of the economy and society can contribute, and sets out the policy actions required to achieve this goal.”

- 20.

- 2050 long-term strategy

“The transition to a climate-neutral society is both an urgent challenge and an opportunity to build a better future for all. ”

“All parts of society and economic sectors will play a role—from the power sector to industry, mobility, buildings, agriculture and forestry. ”

“The EU can lead the way by investing into realistic technological solutions, empowering citizens and aligning action in key areas such as industrial policy, finance and research, while ensuring social fairness for a just transition.”

- 21.

- Communication from the Commission—A Clean Planet for all

“A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy”

- 22.

- Commission guidelines on non-financial reporting

“The non-financial reporting Directive (2014/95/EU) requires large public interest entities with over 500 employees (listed companies, banks, and insurance companies) to disclose certain non-financial information. As required by the directive, the Commission has published non-binding guidelines to help companies disclose relevant non-financial information in a more consistent and more comparable manner.”

- 23.

- Factsheet: Financing Sustainable Growth

“Sustainable finance makes sustainability considerations part of financial decision-making. This means more climate neutral, energy- and resource-efficient and circular projects. Sustainable finance is needed to implement the Commission’s strategy towards achieving the SDGs.”

- 24.

- Renewed sustainable finance strategy and implementation of the action plan on financing sustainable growth

“The recommendations of the High-level expert group on sustainable finance form the basis of the action plan on sustainable finance adopted by the Commission in March 2018”.

“The action plan set out a comprehensive strategy to further connect finance with sustainability.”

- 25.

- EU taxonomy for sustainable activities

“The EU taxonomy is a classification system, establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. It could play an important role helping the EU scale up sustainable investment and implement the European green deal. The EU taxonomy would provide companies, investors and policymakers with appropriate definitions for which economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable. In this way, it should create security for investors, protect private investors from greenwashing, help companies to become more climate-friendly, mitigate market fragmentation and help shift investments where they are most needed.”

- 26.

- Taxonomy Regulation and delegated acts—Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 (Text with EEA relevance)

“The Taxonomy Regulation was published in the Official Journal of the European Union on 22 June 2020 and entered into force on 12 July 2020. It establishes the basis for the EU taxonomy by setting out 4 overarching conditions that an economic activity has to meet in order to qualify as environmentally sustainable.”

- 27.

- Sustainable finance package

“The EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act aims to support sustainable investment by making it clearer which economic activities most contribute to meeting the EU’s environmental objectives.”

“On 9 December 2021, a first delegated act on sustainable activities for climate change mitigation and adaptation objectives of the EU Taxonomy (“Climate Delegated Act”) was published in the Official Journal. The delegated act is applicable from 1 January 2022.”

- 28.

- Transition finance report

“In January 2021, the European Commission asked the Platform to provide advice on transition financing.1 The Commission identified that more work is needed on how the Taxonomy can enable inclusive transition financing for companies and other economic actors working to improve their environmental impact.”

- 29.

- Platform on Sustainable Finance

“The Platform is an advisory body subject to the Commission’s horizontal rules for expert groups. Its main purpose is to advise the European Commission on several tasks and topics related to further developing the EU taxonomy and support the Commission in the technical preparation of delegated acts, in order to implement the EU taxonomy.”

- 30.

- Delegated Act supplementing Article 8 of the Taxonomy Regulation—Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2178 of 6 July 2021 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council by specifying the content and presentation of information to be disclosed by undertakings subject to Articles 19a or 29a of Directive 2013/34/EU concerning environmentally sustainable economic activities, and specifying the methodology to comply with that disclosure obligation (Text with EEA relevance)

“This delegated act specifies the content, methodology and presentation of information to be disclosed by financial and non-financial undertakings concerning the proportion of environmentally sustainable economic activities in their business, investments or lending activities.”

- 31.

- EU taxonomy: Complementary Climate Delegated Act to accelerate decarbonisation

“The Complementary Delegated Act has been published in the Official Journal on 15 July 2022. It will apply from 1 January 2023.”

“The criteria for the specific gas and nuclear activities are in line with EU climate and environmental objectives and will help accelerating the shift from solid or liquid fossil fuels, including coal, towards a climate-neutral future.”

- 32.

- Assessment of nuclear energy—Technical assessment of nuclear energy with respect to the ‘do no significant harm’ criteria of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 (‘Taxonomy Regulation’)

“Inclusion or exclusion of nuclear energy in the EU taxonomy was a debated subject throughout the negotiations on the Taxonomy Regulation. While there are indirect references in the regulation to the issue of nuclear energy (including on radioactive waste), co-legislators ultimately left the assessment of nuclear energy to the Commission as part of its work on the delegated acts establishing the technical screening criteria.”

“The Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG), which was tasked with advising the Commission on the technical screening criteria for the climate change mitigation and adaptation objectives, did not provide a conclusive recommendation on nuclear energy and indicated that a further assessment of the ‘do no significant harm’ aspects of nuclear energy was necessary.”

“As the in-house science and knowledge service of the Commission with extensive technical expertise on nuclear energy and technology, the JRC was invited to carry out such analysis and to draft a technical assessment report on the ‘do no significant harm’ (DNSH) aspects of nuclear energy including aspects related to the long-term management of high-level radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel, consistent with the specifications of Articles 17 and 19 of the Taxonomy Regulation.”

- 33.

- Group of Experts on radiation protection and waste management under Article 31 of the Euratom Treaty

“A group of independent radiation protection and public health experts is attached to the European Commission to help the EU make decisions concerning radioactivity. Its members are appointed by the Scientific and Technical Committee, referred to in the Euratom Treaty Article 31, and for a duration of 5 years.”

“The Commission must consult the group of experts for any updates of the Basic Safety Standards Directive (2013/59/Euratom), which cover safety rules for radiation in applications such as medicine and research.”

- 34.

- Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks

- 35.

- Taxonomy: Final report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance

“This report sets out the TEG’s final recommendations to the European Commission. This report contains recommendations relating to the overarching design of the Taxonomy, as well as guidance on how users of the Taxonomy can develop Taxonomy disclosures. It contains a summary of the economic activities covered by the technical screening criteria.”

- 36.

- Taxonomy Report: Technical Annex

“This report represents the overall view of the members of the Technical Expert Group, and although it represents such a consensus, it may not necessarily, on all details, represent the individual views of member institutions or experts. The views reflected in this Report are the views of the experts only. This report does not reflect the views of the European Commission or its services.”

- 37.

- TEG excel tools to help users of the Taxonomy to implement it in their own activities

- 38.

- EU Green Bond Standard and labels for green financial products

“Once it is adopted by co-legislators, this proposed Regulation will set a gold standard for how companies and public authorities can use green bonds to raise funds on capital markets to finance such ambitious large-scale investments, while meeting tough sustainability requirements and protecting investors.”

“This will be useful for both issuers and investors of green bonds. For example, issuers will have a robust tool to demonstrate that they are funding legitimate green projects aligned with the EU taxonomy. And investors buying the bonds will be able to more easily assess, compare and trust that their investments are sustainable, thereby reducing the risks posed by greenwashing.”

“The new EUGBS will be open to any issuer of green bonds, including companies, public authorities, and also issuers located outside of the EU.”

- 39.

- Supervision by the European Securities Markets Authority (ESMA) of reviewers:

“External reviewers providing services to issuers of European green bonds must be registered with and supervised by the ESMA. This will ensure the quality of their services and the reliability of their reviews to protect investors and ensure market integrity”

- 40.

- The Sustainable Europe Investment Plan—What is the Green Deal Investment Plan?

“The European Green Deal Investment Plan (EGDIP), also referred to as Sustainable Europe Investment Plan (SEIP), is the investment pillar of the Green Deal. To achieve the goals set by the European Green Deal, the Plan will mobilise at least €1 trillion in sustainable investments over the next decade. Part of the plan, the Just Transition Mechanism, will be targeted to a fair and just green transition. It will mobilise at least €100 billion in investments over the period 2021–2027 to support workers and citizens of the regions most impacted by the transition.”

- 41.

- The InvestEU Programme (2021-2027)

“The InvestEU Programme builds on the successful model of the Investment Plan for Europe, the Juncker Plan. It will bring together, under one roof, the European Fund for Strategic Investments and 13 EU financial instruments currently available. Triggering at least €650 billion in additional investment, the Programme aims to give an additional boost to investment, innovation and job creation in Europe.”

- 42.

- Sustainable finance—obligation for investment firms to advise clients on social and environmental aspects of financial products

“The EU’s action plan on sustainable finance seeks to clarify the duties of investment firms to provide their clients with clear advice on the social and environmental risks and opportunities attached to their investments. This initiative aims to:

- 43.

- EU labels for benchmarks (climate, ESG) and benchmarks’ ESG disclosures

“Make benchmark methodologies more transparent when it comes to ESG & put forward standards for the methodology of low-carbon and ESG benchmarks in EU.”

- 44.

- Regulation (EU) 2019/2089 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 as regards EU Climate Transition Benchmarks, EU Paris-aligned Benchmarks and sustainability-related disclosures for benchmarks (Text with EEA relevance)

- 45.

- Teg Interim Report on Climate Benchmarks and Benchmarks’ ESG Disclosures

“The main objectives of the new climate benchmarks are to (i) allow a significant level of comparability of climate benchmarks methodologies while leaving benchmarks’ administrators with an important level of flexibility in designing their methodology; (ii) provide investors with an appropriate tool that is aligned with their investment strategy; (iii) increase transparency on investors’ impact, specifically with regard to climate change and the energy transition; and (iv) disincentivize greenwashing.”

- 46.

- Handbook of Climate Transition Benchmarks, Paris-Aligned Benchmark and Benchmarks’ ESG Disclosures

“This Handbook is a response to frequently asked questions, which the TEG benchmarks subgroup members encountered when presenting the EU Climate Transition Benchmark (EU CTB), the EU Paris Aligned Benchmark (EU PAB), and the benchmarks’ disclosure guidance on environmental, social or governance (ESG) issues. The Handbook commences by (i) clarifying the 7% Reduction Trajectory and (ii) matters of terminology. It continues by explaining (iii) the anti-greenwashing measures, (iv) data sources and estimation techniques as well as (v) related classification. Finally, (vi) ESG disclosure matters are discussed and (vii) further aspects are highlighted. Detailed appendices provide computation and sector mapping guidance.”

- 47.

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/804 of 16 February 2022 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council by specifying rules of procedure for measures applicable to the supervision by the European Securities Markets Authority of certain benchmark administrators (Text with EEA relevance)

- 48.

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/805 of 16 February 2022 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council by specifying fees applicable to the supervision by the European Securities Markets Authority of certain benchmark administrators (Text with EEA relevance)

- 49.

- EU Climate Transition Benchmarks Regulation—Implementing and delegated acts: full list

- 50.

- Final Report—Guidelines on Disclosure Requirements Applicable to Credit Ratings

“To strengthen disclosure on how ESG factors are being considered, ESMA updated its Guidelines on disclosure requirements for credit ratings in July 2019 and has started checking how credit rating agencies apply these new guidelines in April 2020. Moreover, in December 2019, the Commission launched a study on sustainability ratings and research that will explore the types of products that are provided in for ratings and market research, the main players, data sourcing, transparency of methodologies and potential shortcomings in the market. The study is expected to be completed by the Summer 2020.”

- 51.

- Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector (Text with EEA relevance)

“This Regulation aims to reduce information asymmetries in principal-agent relationships with regard to the integration of sustainability risks, the consideration of adverse sustainability impacts, the promotion of environmental or social characteristics, and sustainable investment, by requiring financial market participants and financial advisers to make pre-contractual and ongoing disclosures to end investors when they act as agents of those end investors (principals).”

“This Regulation maintains the requirements for financial market participants and financial advisers to act in the best interest of end investors, including but not limited to, the requirement of conducting adequate due diligence prior to making investments, provided for in Directives 2009/65/EC, 2009/138/EC, 2011/61/EU, 2013/36/EU, 2014/65/EU, (EU) 2016/97, (EU) 2016/2341, and Regulations (EU) No 345/2013 and (EU) No 346/2013, as well as in national law governing personal and individual pension products. In order to comply with their duties under those rules, financial market participants and financial advisers should integrate in their processes, including in their due diligence processes, and should assess on a continuous basis not only all relevant financial risks but also including all relevant sustainability risks that might have a relevant material negative impact on the financial return of an investment or advice. Therefore, financial market participants and financial advisers should specify in their policies how they integrate those risks and publish those policies.”

- 52.

- Eba Report on Undue Short-Term Pressure from the Financial Sector on Corporations

“The report includes important information from public sources as background and context. First, the overview of academic literature illustrates some evidence of the existence of short-termism in capital markets, while it provides balanced findings with regard to the relative roles of bank-based, as opposed to stock-based, financial systems in supporting short-termism. Second, while EU banks have adopted a diversity of business models, they apply an average 3- to 5-year time horizon for business planning and strategy-setting purposes. Time horizons are driven by a number of factors that potentially hamper the adoption of longer term strategies and activities. Furthermore, the traditional time horizons of European Union (EU) banks seem to not allow long-term and sustainability challenges, such as climate-related risks, to be fully taken into account and tackled.”

- 53.

- EIOPA Potential undue short-term pressure from financial markets on corporates: Investigation on European insurance and occupational pension sectors

“Life insurers and pension funds are usually considered long-term investors: based on their business models, they receive savings from the households with the promise to paying back earlier in an unexpected event or in a longer term. Predictability of cash flows is key for pricing and efficiently managing the savings received. This predictability is provided by making an appropriate selection of risks that are pooled together and applying the big numbers law to sufficiently large portfolios; such characteristics typically allows these investors to follow longer term strategies.”

“Corporates, in general, benefit from the existence of efficient financial markets to cover their funding needs. Particularly relevant are the investment habits of life insurers and pension funds that ensure sufficiently deep, liquid and transparent markets for long-dated financial instruments.”

“For these reasons, it is key to monitor whether the insurance and institutions for occupational retirement provision (IORPs) sectors continue to fulfil their alleged roles as long-term investors and, in the case of deviations, then investigate the reasons for the deviation and the potential solutions.”

- 54.

- ESMA Report Undue short-term pressure on corporations

“As regards the comment on the potential short-term effect of the use of benchmarks to measure performance, ESMA notes that there are legitimate investor protection reasons to assess the performance of asset managers against market benchmarks as it allows investors to compare the performance of their collective portfolio management options. In this context, the UCITS KIID requires the disclosure of the reference benchmark as well as its historical performance to the end investor. ESMA observes that this requirement is driven by investor protection concerns which outweigh the potential short- term impact.”

- 55.

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of the Regions Action Plan: Financing Sustainable Growth

“Finance supports the economy by providing funding for economic activities and ultimately jobs and growth. Investment decisions are typically based on several factors, but those related to environmental and social considerations are often not sufficiently taken into account, since such risks are likely to materialize over a longer time horizon. It is important to recognize that taking longer-term sustainability interests into account makes economic sense and does not necessarily lead to lower returns for investors.”

“‘Sustainable finance’ generally refers to the process of taking due account of environmental and social considerations in investment decision-making, leading to increased investments in longer-term and sustainable activities. More specifically, environmental considerations refer to climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the environment more broadly and related risks (e.g., natural disasters). Social considerations may refer to issues of inequality, inclusiveness, labor relations, investment in human capital and communities. Environmental and social considerations are often intertwined, as especially climate change can exacerbate existing systems of inequality. The governance of public and private institutions, including management structures, employee relations and executive remuneration, plays a fundamental role in ensuring the inclusion of social and environmental considerations in the decision-making process.”

“This Action Plan on sustainable finance is part of broader efforts to connect finance with the specific needs of the European and global economy for the benefit of the planet and our society.”

- 56.

- Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism-COM/2021/564 final

“The first option for a CBAM is an import carbon tax, paid by the importer when products enter the EU. The tax would be collected by customs at the border based on a tax reflecting the price of carbon in the Union combined with a default carbon intensity of the products. Importers would have the opportunity to claim a reduction of the CBAM based on their individual carbon footprint and any carbon price paid in the country of production.”

“The second option involves the application on imports of a system that replicates the EU ETS regime applicable to domestic production. This option entails—similar to the system of allowances under the EU ETS—the surrendering of certificates (‘CBAM certificates’) by importers based on embedded emission intensity of the products they import into the Union, and purchased at a price corresponding to that of the EU ETS allowances at any given point in time. These certificates will not be linked to the EU ETS system of allowances but will mirror the price of these allowances to ensure a coherent approach to the pricing under the EU ETS. National climate authorities will administer the sale of the CBAM certificates and importers will submit declarations of verified embedded emissions in the imported products to these authorities tasked with managing the CBAM and surrender a number of CBAM certificates corresponding to the declared emissions. Such declaration and surrendering will occur—similar to that under the EU ETS—at a yearly reconciliation exercise taking place in the year following the year of importation and based on yearly trade import volumes. The carbon emission intensity of products would be based on default values; however, importers would be given the opportunity, at the moment of the yearly reconciliation exercise, to claim a reduction of the CBAM on the basis of their individual emission performance. They would also be entitled to claim a reduction of the CBAM for any carbon price paid in the country of production (which is not rebated or in other way compensated upon export).”

“Option 3 operates in the same way as option 2, however the carbon price of imports is based on actual emissions from third country producers rather than on a default value based on EU producers’ averages. Under this option, the importer will have to report the actual emissions embedded in the product and surrender a corresponding number of CBAM certificates.”

“Option 4 would apply in the same way as option 3. It consists of surrendering CBAM certificates on imported products. However, this option considers also a 10 years phasing in period starting in 2026 during which the free allocations of allowances under the EU ETS would be gradually phased out by 10 percentage points each year and the CBAM would be phased in. During this phasing in period, the CBAM would be reduced proportionally to the amount of free allowances distributed in a given sector.”

“Option 5 is a variant of Option 3 with a scope extended further down in the value chain. Carbon-intensive materials that are part of semi-finished and finished products would be covered along the value chain. For imports, the CBAM would again be based on the actual emissions from third country producers.”

“Option 6 consists of an excise duty on carbon-intensive materials covering consumption in the Union of both domestic and imported products, besides the continuation of the EU ETS including the free allocation of allowances covering production in the EU.”

- 57.

- Guidance Note on approaches to quantify, verify, validate, monitor and report (upstream emission reductions)

“As part of the EU climate and energy legislation in place to achieve the greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets for 2020 the Fuel Quality Directive (FQD)1 obliges fuels suppliers to reduce the greenhouse gas intensity (life cycle greenhouse gas emissions per unit of energy) of the fuel and energy supplied by them by 6% in 2020 compared to a fuel baseline standard of 2010. The rules on calculation methods laid down in Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 (the implementing Council Directive)2 include the possibility to account for upstream emission reductions and to take those emission reductions into account in the compliance assessment of their/that obligation under the FQD.”

“This document aims to facilitate the implementation by Member States of this legislation by providing non-binding guidance on approaches to quantify, verify, validate, monitor and report upstream emission reductions, as called for in Recital (6) of the implementing Council Directive. It provides practical aspects on certain topics identified in a series of informal discussions3 held with Member States representatives following the adoption of the implementing Council Directive.”

“No obligation to use UER as a compliance option. The Fuel Quality Directive and Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 foresee several options for suppliers to reduce the GHG intensity of fuels and energy (and thereby comply with the obligation established in Article 7a of the FQD: (a) blend/supply biofuels, (b) supply fuels with lower GHG intensity such as LPG, CNG and H2, (c) provide electricity for road transport or (d) reduce upstream emission. Suppliers can combine these options as appropriate. There is no obligation to use any specific option.”

“Possibility to use diverse emission schemes for calculating and certifying emission reductions. Recital 3 of the Council Directive states that, “In order to facilitate the claiming of UERs by suppliers, the use of various emission schemes should be allowed for calculating and certifying emission reductions.” In this context, a single upstream emission reduction project generating eligible UERs may be considered to constitute a ‘scheme’.”

“Additionality. For emission reductions to be eligible to be claimed as UERs they must be additional to any emissions changes that would have been expected in the most likely counterfactual scenario.”

“No double counting. Any particular batch of emission reductions from a given project may only be claimed against FQD GHG emission reduction obligations or other emission reductions targets once. These emission reductions cannot be claimed under the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism or the Joint Implementation. Similarly, upstream emission reductions that have been accounted for third party emission reductions schemes shall not be eligible under the FQD.”

“Dissociation of upstream reduction and fuel supplied on the market. All GHG reduction projects in any country at upstream production and extraction sites of non- biological raw material for the production of fuels for transport supplied for uses covered by the Fuel Quality Directive should be considered as potentially eligible, so long as they are consistent with the definition in Article 2 of the Council Directive.”

- 58.

- EBA Roadmap on sustainable finance

“The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap outlining the objectives and timeline for delivering mandates and tasks in the area of sustainable finance and environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks. The roadmap explains the EBA’s sequenced and comprehensive approach over the next three years to integrate ESG risks considerations in the banking framework and support the EU’s efforts to achieve the transition to a more sustainable economy.”

“Numerous legislative acts and initiatives allocate to the EBA new mandates and tasks in the area of sustainable finance and ESG risks. Most of these mandates and tasks are closely linked to the EBA’s broader objective of contributing to the stability, resilience, and orderly functioning of the financial system. These mandates and tasks cover the three pillars of the banking framework, i.e., market discipline, supervision and prudential requirements, as well as other areas related to sustainable finance and the assessment and monitoring of ESG risks.”

“This roadmap on sustainable finance builds on and replaces the EBA’s first action plan on sustainable finance published in December 2019. The roadmap ensures continuity of actions assumed under the previous action plan, while accommodating the necessary adjustments following the market and regulatory developments, including new mandates and new areas of focus.”

“In the area of transparency and disclosures, the EBA will continue its work related to the development and implementation of institutions’ ESG risks and wider sustainability disclosures. Similarly, the EBA will continue its efforts to ensure that ESG factors and risks are adequately integrated in institutions’ risk management framework and in their supervision, including through further developments on climate stress tests. In the area of prudential regulation, the EBA has initiated an assessment of whether amendments to the existing prudential treatment of exposures to incorporate environmental and social considerations would be justified. Furthermore, the EBA will contribute to the development of green standards and labels, and measures to address emerging risks in this field, such as greenwashing. Finally, the EBA will be assessing and monitoring developments in sustainable finance and institutions’ ESG risk profile, including on the basis of the expected supervisory reporting.”

“The roadmap was developed based on the current state of the regulatory framework and reflects the EBA’s current expectations regarding specific mandates and tasks. However, considering the ongoing regulatory developments, including the review of the banking package (CRR/CRD), the scope and timelines of specific tasks will only be fully known once the legislative processes are finalised.”

- 59.

- European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) data from EUTL

“The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) is a central instrument of the EU’s policy to fight climate change and achieve cost-efficient reductions of greenhouse gas emissions. It is the world’s biggest carbon market. Data about the EU emission trading system (ETS). The EU ETS data viewer provides aggregated data on emissions and allowances, by country, sector and year. The data mainly comes from the EU Transaction Log (EUTL). Additional information on auctioning and scope corrections is included.”

- 60.

- Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda 2021–2027—Clean Hydrogen Joint Undertaking

“This document represents the Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda (SRIA) 2021-2027 of the Clean Hydrogen Joint Undertaking (hereafter also Clean Hydrogen JU). It covers therefore the duration of Horizon Europe and identifies the key priorities and the essential technologies and innovations required to achieve the objectives of the joint undertaking.”

“The Clean Hydrogen JU is the continuation of the successful Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Joint Undertakings (FCH JU and FCH 2 JU), under FP7 and Horizon 2020 (H2020) respectively. It is set up in the form of an institutionalised partnership under the Research and Innovation Framework Programme Horizon Europe.”

- 61.

- Intelligent transport systems

“Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) are vital to increase safety and tackle Europe’s growing emission and congestion problems. They can make transport safer, more efficient and more sustainable by applying various information and communication technologies to all modes of passenger and freight transport. Moreover, the integration of existing technologies can create new services. ITS are key to support jobs and growth in the transport sector. But in order to be effective, the roll-out of ITS needs to be coherent and properly coordinated across the EU.”

“The European Commission is working with Member States, industry and public authorities to find common solutions to the various bottlenecks for deployment. Through financial instruments the European Commission supports innovative projects in ITS and through legislative instruments it ensures that ITS are rolled out consistently.”

“In the coming years, the digitalisation of transport in general and ITS in particular are expected to take a leap forwards. As part of the Digital Single Market Strategy, the European Commission aims to make more use of ITS solutions to achieve a more efficient management of the transport network for passengers and business. ITS will be used to improve journeys and operations on specific and combined modes of transport. The European Commission also works to set the ground for the next generation of ITS solutions, through the deployment of Cooperative-ITS, paving the way for automation in the transport sector. C-ITS are systems that allow effective data exchange through wireless technologies so that vehicles can connect with each other, with the road infrastructure and with other road users.”

- 62.

- Digital Single Market Strategy

“Digital technology is changing people’s lives. The EU’s digital strategy aims to make this transformation work for people and businesses, while helping to achieve its target of a climate-neutral Europe by 2050. The Commission is determined to make this Europe’s “Digital Decade”. Europe must now strengthen its digital sovereignty and set standards, rather than following those of others—with a clear focus on data, technology, and infrastructure.”

- 63.

- Horizon Europe

“Horizon Europe—#HorizonEU—is the European Union’s flagship Research and Innovation programme, part of the EU-long-term Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) with a budget of €95,5bn (including €75,9bn from the MFF and €5bn from the Next Generation Europe) to spend over a seven-year period (2021–2027).”

- 64.

- Recovery and Resilience Facility

“As part of a wide-ranging response, the aim of the Recovery and Resilience Facility is to mitigate the economic and social impact of the coronavirus pandemic and make European economies and societies more sustainable, resilient and better prepared for the challenges and opportunities of the green and digital transitions.”

“The Facility is a temporary recovery instrument. It allows the Commission to raise funds to help Member States implement reforms and investments that are in line with the EU’s priorities and that address the challenges identified in country-specific recommendations under the European Semester framework of economic and social policy coordination. It makes available €723.8 billion (in current prices) in loans (€385.8 billion) and grants (€338 billion) for that purpose”

“The RRF helps the EU achieve its target of climate neutrality by 2050 and sets Europe on a path of digital transition, creating jobs and spurring growth in the process.”

- 65.

- Strategic Plans 2020-2024

“The purpose of the strategic plans and management plans is to help Commission departments align their work with the Commission’s overall policy objectives, and plan and manage activities in order to make the most efficient use of resources.”

“In their strategic plans, Commission departments describe how they will contribute to the 6 political priorities of the Commission. They define specific objectives for their department for a five-year period as well as indicators to help them track progress. All departments report on progress each year in their annual activity reports.”

- 66.

- Regulation (EU) No 1315/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on Union guidelines for the development of the trans-European transport network and repealing Decision No 661/2010/EU Text with EEA relevance

“This Regulation applies to the trans-European transport network as shown on the maps contained in Annex I. The trans-European transport network comprises transport infrastructure and telematic applications as well as measures promoting the efficient management and use of such infrastructure and permitting the establishment and operation of sustainable and efficient transport services.”

“The infrastructure of the trans-European transport network consists of the infrastructure for railway transport, inland waterway transport, road transport, maritime transport, air transport and multimodal transport, as determined in the relevant sections of Chapter II.”

- 67.

- Fit for 55

“The Fit for 55 package is a set of proposals to revise and update EU legislation and to put in place new initiatives with the aim of ensuring that EU policies are in line with the climate goals agreed by the Council and the European Parliament.”

“The package of proposals aims at providing a coherent and balanced framework for reaching the EU’s climate objectives, which:

- 68.

- COM/2020/301—A hydrogen strategy for a climate neutral Europe

“There are many reasons why hydrogen is a key priority to achieve the European Green Deal and Europe’s clean energy transition. Renewable electricity is expected to decarbonize a large share of the EU energy consumption by 2050, but not all of it. Hydrogen has a strong potential to bridge some of this gap, as a vector for renewable energy storage, alongside batteries, and transport, ensuring back up for seasonal variations and connecting production locations to more distant demand centers. In its strategic vision for a climate-neutral EU published in November 2018, the share of hydrogen in Europe’s energy mix is projected to grow from the current less than 2% to 13–14% by 2050”

“In the integrated energy system of the future hydrogen will play a role, alongside renewable electrification and a more efficient and circular use of resources. Large-scale deployment of clean hydrogen at a fast pace is key for the EU to achieve a higher climate ambition, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by minimum 50% and towards 55% by 2030, in a cost effective way.”

“Investment in hydrogen will foster sustainable growth and jobs, which will be critical in the context of recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The Commission’s recovery plan highlights the need to unlock investment in key clean technologies and value chains. It stresses clean hydrogen as one of the essential areas to address in the context of the energy transition, and mentions a number of possible avenues to support it.”

“Moreover, Europe is highly competitive in clean hydrogen technologies manufacturing and is well positioned to benefit from a global development of clean hydrogen as an energy carrier. Cumulative investments in renewable hydrogen in Europe could be up to EUR 180–470 billion by 2050, and in the range of €3-18 billion for low-carbon fossil-based hydrogen. Combined with EU’s leadership in renewables technologies, the emergence of a hydrogen value chain serving a multitude of industrial sectors and other end uses could employ up to 1 million people, directly or indirectly. Analysts estimate that clean hydrogen could meet 24% of energy world demand by 2050, with annual sales in the range of €630 billion.”

- 69.

- COM/2021/557 Amendment to the Renewable Energy Directive to implement the ambition of the new 2030 climate target

“The European Green Deal (EGD) establishes the objective of becoming climate neutral in 2050 in a manner that contributes to the European economy, growth and jobs. This objective requires a greenhouse as emissions reduction of 55% by 2030 as confirmed by the European Council in December 2020. This in turn requires significantly higher shares of renewable energy sources in an integrated energy system. The current EU target of at least 32% renewable energy by 2030, set in the Renewable Energy Directive (REDII), is not sufficient and needs to be increased to 38–40%, according to the Climate Target Plan (CTP). At the same time, new accompanying measures in different sectors in line with the Energy System Integration, the Hydrogen, the Offshore Renewable Energy and the Biodiversity Strategies are required to achieve this increased target.”

“The overall objectives of the revision of REDII are to achieve an increase in the use of energy from renewable sources by 2030, to foster better energy system integration and to contribute to climate and environmental objectives including the protection of biodiversity, thereby addressing the intergenerational concerns associated with global warming and biodiversity loss. This revision of REDII is essential to achieve the increased climate target as well as to protect our environment and health, reduce our energy dependency, and contribute to the EU’s technological and industrial leadership along with the creation of jobs and economic growth.”

- 70.

- COM/2021/561 Regulation of The European Parliament and of the Council on ensuring a level playing field for sustainable air transport

“Air connectivity is an essential driver of mobility for EU citizens, of development for EU regions and of growth for the economy as a whole. High levels of air connectivity within the EU, as well as to and from the EU, are best ensured when the EU air transport market functions as a level playing field, where all market actors can operate based on equal opportunities. When occurring, market distortions risk putting aircraft operators or airports at disadvantage towards competitors. In turn, this can result in a loss of competitiveness of the industry, and a loss of air connectivity for citizens and businesses.”

“In particular, it is essential to ensure a level playing field across the EU air transport market, when it comes to the use of aviation fuel. Indeed, aviation fuel accounts for a substantial share of aircraft operators’ costs, i.e., up to 25% of operational costs. Variations in the price of aviation fuel can have important impacts on aircraft operators’ economic performance. Furthermore, differences in the price of aviation fuel between geographic locations, as is currently the case between EU airports or between EU and non-EU airports, can lead aircraft operators to adapt their refuelling strategies for economic reasons.”

“Practices such as ‘fuel tankering’ occur when aircraft operators uplift more aviation fuel than necessary at a given airport, with the aim to avoid refuelling partially or fully at a destination airport where aviation fuel is more expensive. Fuel tankering leads to higher fuel burn than necessary, hence higher emissions, and undermines fair competition in the Union air transport market. Besides being contrary to the Union’s efforts to decarbonise aviation, fuel tankering is also detrimental to healthy competition between aviation market players. With the introduction and the ramp-up of sustainable aviation fuels at Union airports, practices of fuel tankering may be exacerbated as a result of increased aviation fuel costs.”

“In respect to fuel tankering, the present Regulation therefore aims restore and preserve a level playing field in the air transport sector, while at the same time avoiding any adverse environmental effect.”

“The Commission adopted in December 2020 the Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy. This strategy sets out the objective to boost the uptake of sustainable aviation fuels. Sustainable aviation fuels have the potential to deliver a major contribution to achieving the increased EU climate target for 2030 and the EU’s climate neutrality objective. For the purpose of this initiative, sustainable aviation fuels means liquid drop-in fuels substitutable to conventional aviation fuel. In order to decrease significantly its emissions, the aviation sector needs to reduce its current exclusive reliance on fossil jet fuel and accelerate its transition to innovative and sustainable types of fuels and technologies. While alternative propulsion technologies for aircraft such as powered by electricity or hydrogen are making promising advances, their introduction to commercial use will take a considerable effort and time to prepare. Because air transport needs to address its carbon footprint on all flight ranges already by 2030, the role of sustainable aviation liquid fuels will be essential. For this reason, measures are also needed to increase the supply and use of sustainable aviation fuels at Union airports.”

References

- Ticau, I.; Cioranu, A.; Stoicescu, V. Community branding in the dawn of a sustainable fourth industrial revolution. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Scientific Conference New Challenges in Economic and Business Development—2022: Responsible Growth, Riga, Latvia, 13 May 2022; pp. 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pouikli, K. Towards mandatory green public procurement (GPP) requirements under the EU green deal: Reconsidering the role of public procurement as an environmental policy tool. ERA Forum 2021, 21, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.; Heindlmaier, A. Administering the union citizen in need: Between welfare state bureaucracy and migration control. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2021, 31, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.; Peters, B.G. Identity and Representation: Representative Bureaucracy in the European Union. In Political Identification in Europe: Community in Crisis? Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Aityan, S.K. The research process. In Business Research Methodology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sakha, S.; Jin, Y. Strengthening the business environment for productivity convergence. In OECD Economic Surveys: Romania 2022; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cremades, L.V.; Canals Casals, L. Analysis of the future of mobility: The battery electric vehicle seems just a transitory alternative. Energies 2022, 15, 9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterlepper, S.; Fischer, M.; Claßen, J.; Huth, V.; Pischinger, S. Concepts for hydrogen internal combustion engines and their implications on the exhaust gas aftertreatment system. Energies 2021, 14, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele Candelaresi, Antonio Valente, Diego Iribarren, Javier Dufour, Giuseppe Spazzafumo, Novel short-term national strategies to promote the use of renewable hydrogen in road transport: A life cycle assessment of passenger car fleets partially fuelled with hydrogen. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160325. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tang, G. A review on environmental efficiency evaluation of new energy vehicles using life cycle analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabie, C. Electric vehicles optimism versus the energy market reality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, F. On the sustainability of electric vehicles: What about their impacts on land use? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 66, 102680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kool, C.; Engelen, P.-J. Analyzing the business case for hydrogen-fuel infrastructure investments with endogenous demand in The Netherlands: A real options approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtner, C. Wise governance—Elements of the digital strategies of municipalities. Smart Cities Reg. Dev. J. 2022, 6, 23–29. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/pop/journl/v6y2022i2p23-29.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Harizaj, M.; Ndreu, A. Living in smart cities and green world. Smart Cities Reg. Dev. J. 2022, 6, 27–40. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/s/pop/journl.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Wei, H. International Conference on Transportation and Development 2022: Transportation Planning and Workforce Development; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fantin Irudaya Raj, E.; Appadurai, M. Internet of things-based smart transportation system for smart cities. In Intelligent Systems for Social Good; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Dhakal, P.R.; Wu, Z. The impact of high-speed railway on China’s regional economic growth based on the perspective of regional heterogeneity of quality of place. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruchalu, C.N.; Pichardo, M.S.; Bharadwaj, M.; Rodriguez, C.B.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Bergmark, R.W.; Bates, D.W.; Ortega, G. The expanding digital divide: Digital health access inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.M.; Tyagi, A.K.; Sreenath, N. The future with industry 4.0 at the core of society 5.0: Open issues, future opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), Coimbatore, India, 27–29 January 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vrabie, C. Just Do It—Spreading Use of Digital Services. EGPA Conference 2009. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2673743 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Arthurs, P.; Gillam, L.; Krause, P.; Wang, N.; Halder, K.; Mouzakitis, A. A taxonomy and survey of edge cloud computing for intelligent transportation systems and connected vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 6206–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, A.; Nencioni, G. The role of 5G technologies in a smart city: The case for intelligent transportation system. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffash, S.; Nguyen, A.T.; Zhu, J. Big data algorithms and applications in intelligent transportation system: A review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strambo, C.; Xylia, M.; Dawkins, E.; Suljada, T. The Impact of the New EU Emissions Trading System on Households; SEI: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eicke, L.; Weko, S.; Apergi, M.; Marian, A. Pulling up the carbon ladder? Decarbonization, dependence, and third-country risks from the European carbon border adjustment mechanism. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venzke, I.; Vidigal, G. Are trade measures to tackle the climate crisis the end of differentiated responsibilities? The case of the EU carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). In Amsterdam Law School Legal Studies Research Paper; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Held, B.; Leisinger, C.; Runkel, M.; CAN-Europe, G.; Deutschland eV, K.-A.; Deutschland, W. Criteria for an Effective and Socially Just EU ETS 2; Germanwatch: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, I.; Sousa, M.J.; Dionísio, A. Employer branding as a talent management tool: A systematic literature revision. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, G. ESG disclosure and financial performance: Moderating role of ESG investors. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBA Roadmap on Sustainable Finance. European Banking Authority. Available online: https://www.eba.europa.eu/eba-publishes-its-roadmap-sustainable-finance (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Tolliver, C.; Keeley, A.R.; Managi, S. Green bonds for the Paris agreement and sustainable development goals. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 064009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, F.; Pandimiglio, A. The role of ESG scoring and greenwashing risk in explaining the yields of green bonds: A conceptual framework and an econometric analysis. Glob. Financ. J. 2022, 52, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Schmittmann, J.M. Green Bond Pricing and Greenwashing under Asymmetric Information; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, S.; Del Baldo, M.; Caputo, F.; Venturelli, A. Voluntary disclosure of sustainable development goals in mandatory non-financial reports: The moderating role of cultural dimension. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2022, 33, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rant, V. Regulating the Green Transition and Sustainable Finance in the European Union. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4108232 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Redert, B. From clubs to hubs: Analysing lobbying networks in EU financial regulation after crisis. J. Public Policy 2022, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Luo, L.; Shamsuddin, A.; Tang, Q. Corporate carbon accounting: A literature review of carbon accounting research from the Kyoto protocol to the Paris agreement. Account. Financ. 2022, 62, 261–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Kesidou, E. Sustainability-oriented capabilities for eco-innovation: Meeting the regulatory, technology, and market demands. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Ciasullo, M.V.; Douglas, A.; Kumar, S. Environmental social governance (ESG) and total quality management (TQM): A multi-study meta-systematic review. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, C.; Hilloulin, B.; Boisserie, B.; Thomas, M.; Guignard, Q.; Rozière, E. Open-source carbon footprint estimator: Development and university declination. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R. ISO 26000 and the standardization of strategic management processes for sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14007 & ISO 14008; Environmental Management Systems Standards Facing Natural Capital Accounting. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Vasa, A.; Vartanyan, M.; Netto, M. A Novel Database for Green Bonds to Support Investment Analysis and Decision Making, Research, and Regulatory Decisions: The Green Bond Transparency Platform; GFL: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ozili, P.K. Policy perspectives in promoting green finance. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, S. Alternative Transport Fuels Elements of the European Union’s “Fit for 55” Package; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- van Renssen, S. The hydrogen solution? Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco Martín, B. Analysis of the European Strategy for Hydrogen; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Andalusia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, T.; Dardenne, J. Manager, Assessment of carbon leakage of potential for European Aviation; TE ORG: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gherasim, D.-P. A Guide to Solve EU’s Hydrogen Dilemmas; IFRI: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coppitters, D.; Verleysen, K.; De Paepe, W.; Contino, F. How can renewable hydrogen compete with diesel in public transport? Robust design optimization of a hydrogen refueling station under techno-economic and environmental uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotenboer, A.H.; Veenstra, A.A.; uit het Broek, M.A.; Ursavas, E. A green hydrogen energy system: Optimal control strategies for integrated hydrogen storage and power generation with wind energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, S. EU Taxonomy: Delegated Acts on Climate, and Nuclear and Gas; Policy Commons–Coherent Digital: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Andhov, M. Contracting Authorities and Strategic Goals of Public Procurement—A Relationship Defined by Discretion? SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abdou, A.; Czibik, Á.; Tóth, B.; Fazekas, M. COVID-19 emergency public procurement in Romania: Corruption risks and market behavior. Gov. Transpar. Inst. 2021, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M.; Daddi, T. What factors influence the uptake of GPP (green public procurement) practices? New evidence from an Italian survey. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 82, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proposal Action Domain | Official Document (as in Appendix A) | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Emissions | (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 35, 36, 37, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 49, 50, 51, 55, 56, 57, 59, 68) | Emissions trading for roads Emissions trading for buildings CO2 emissions standards for cars and vans EU Emissions Trading System Aviation Initiative Carbon Adjustment Mechanism |

| Social Climate | (1, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 25, 29, 31, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 58, 60) | Funding Sharing Regulation |

| Land Use | (2, 19, 20, 25, 31, 55, 56) | Land Use Change |

| Forests | (3, 5, 6, 7, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 25, 30, 31, 55, 56) | Forestry Regulation EU Forest Strategy |

| Energy | (1, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 31, 32, 33, 34, 38, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 49, 50, 51, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 68, 68, 69, 70) | Aviation Initiative Maritime Initiative Energy Taxation Renewable Energy Directive Energy Efficiency Directive |

| Renewable | (4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 49, 50, 51, 55, 56, 58, 59, 67, 69) | Aviation Initiative Renewable Energy Directive |

| Alternative Fuels | (4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 25, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 51, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 68, 70) | Infrastructure Regulation |

| Standards | (1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 22, 25, 26, 27, 30, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 66, 70) | CO2 emissions standards for cars and vans |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoicescu, V.; Bițoiu, T.I.; Vrabie, C. The Smart Community: Strategy Layers for a New Sustainable Continental Framework. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 410-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6010020

Stoicescu V, Bițoiu TI, Vrabie C. The Smart Community: Strategy Layers for a New Sustainable Continental Framework. Smart Cities. 2023; 6(1):410-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoicescu, Vlad, Teodora Ioana Bițoiu, and Cătălin Vrabie. 2023. "The Smart Community: Strategy Layers for a New Sustainable Continental Framework" Smart Cities 6, no. 1: 410-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6010020

APA StyleStoicescu, V., Bițoiu, T. I., & Vrabie, C. (2023). The Smart Community: Strategy Layers for a New Sustainable Continental Framework. Smart Cities, 6(1), 410-444. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6010020