1. Introduction

Cancer represents a significant global public health challenge, accounting for 16.7% of total deaths and 23.3% of deaths due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [

1,

2]. Since 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) has designated cancer as one of the four major NCDs requiring priority management, along with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic respiratory diseases. As cancer survival rates have steadily improved, managing health behaviors has become increasingly critical in reducing recurrence risk and enhancing long-term outcomes [

2]. In the context of cancer survivorship, health behaviors refer to modifiable lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity that are strongly associated with prognosis, quality of life, and long-term outcomes. According to the 2022 Global Cancer Observatory report by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), colorectal cancer ranked third in the global incidence rate (9.6%), and gastric cancer ranked fifth (4.8%). In terms of mortality, colorectal cancer (9.3%) and gastric cancer (6.8%) ranked second and fourth, respectively, underscoring their substantial global burden. Moreover, the 1- to 3-year prevalence rates of these cancers rank among the highest globally, emphasizing their importance in cancer control strategies [

3].

In South Korea, the prevalence of colorectal and gastric cancers exhibits high prevalence rates. The age-standardized prevalence rates are 647.5 per 100,000 for gastric cancer and 592.7 per 100,000 for colorectal cancer, making them the most prevalent cancers after thyroid cancer [

4]. According to the National Cancer Information Center, the age-standardized incidence rates of gastric and colorectal cancers in South Korea exceed those in the United States and the United Kingdom while remaining comparable to those in Japan [

4]. This regional trend may reflect differences in health behaviors, cultural practices, and environmental exposures that collectively contribute to the elevated burden of gastrointestinal cancers in East Asia.

To address the growing cancer burden, the South Korean government enacted the Cancer Control Act and implemented the Fourth Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan (2021–2025) [

5]. However, despite these policy efforts, there remains a relative lack of focus on self-management support and community resources to assist cancer patients in managing physical and psychological challenges and maintaining healthy behaviors.

Health behaviors, defined as intentional actions taken to maintain or improve health, are critical to disease prevention and health promotion [

6]. Cancer patients and survivors often undergo changes in health behaviors after diagnosis, which significantly influences cancer recurrence and mortality [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Previous studies have shown that colorectal cancer patients who maintain physical activity exhibit lower recurrence and mortality rates [

7], whereas those who continue smoking have higher mortality rates [

8]. Despite initial efforts, many patients fail to sustain positive health behaviors over time, including physical activity and smoking cessation [

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, a study of breast cancer survivors observed a rising trend in alcohol consumption over time after diagnosis, implying a decline in adherence to healthy behaviors over time [

10]. These findings emphasize the need for sustained interventions to support long-term maintenance of healthy behaviors among cancer patients and survivors.

Despite their critical role in cancer outcomes, changes in health behaviors remain inherently challenging, as they are shaped by long-standing habits and influenced by social and environmental factors [

6]. Cancer patients and survivors, in particular, experience substantial physical and psychological burdens throughout the diagnosis and treatment, further complicating the adoption and maintenance of healthy behaviors. In light of these challenges, comprehensive policy interventions and supportive environments are essential to promote sustained improvements in health behavior [

6].

Previous studies have primarily focused on the impact of health behaviors on cancer incidence, whereas few studies have examined changes in health behaviors among cancer patients and survivors. Therefore, this study aims to examine differences in health behaviors according to survival status and time since diagnosis among individuals with gastric or colorectal cancer, using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES, 2014–2021). Furthermore, it examines whether temporal patterns in health behaviors emerged based on time since diagnosis. The findings of this study provide empirical evidence for the development of self-management support programs and community-based interventions within national cancer control policies.

2. Results

From the 2014–2021 KNHANES data, a total of 656 individuals aged 40 years or older reported having been diagnosed with gastric or colorectal cancer. Among them, 441 were classified as survivors and 215 as current patients (

Supplementary Table S1). There was no significant difference in sex distribution between the two groups. However, survivors tended to be older, and their mean time since diagnosis was notably longer, averaging over 10 years. Over 40% of survivors had been diagnosed more than 10 years prior, suggesting potential bias due to long-term survivorship. Therefore, to reduce this bias, we limited our analysis to individuals diagnosed within the past 10 years.

A total of 478 participants met this criterion, comprising 267 survivors and 211 current patients (

Table 1). No significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of sex. However, the mean age was significantly higher among survivors (

p = 0.0270), although age group comparisons did not yield statistically significant differences (

p = 0.3925). Survivors still had a longer time since diagnosis, with over 60% having been diagnosed more than five years earlier. In contrast, the majority of current patients have been diagnosed within the past three years. When comparing health behaviors between the patient and survivor groups, a significant difference was found in alcohol consumption (

p = 0.0002). The proportion of current drinkers was 29.9% among patients, whereas nearly half (49.2%) of survivors reported current alcohol use.

We further examined whether time since diagnosis was associated with differences in health behaviors within the patient group (

Table 2). Patients were divided into the following two groups: those diagnosed within the past three years and those diagnosed more than three years ago. While no significant differences were found in sex, age, or most health behaviors, a notable difference was observed in alcohol consumption. Only 25.4% of those diagnosed within the past three years reported current drinking, compared to 40.9% of those with more than three years since diagnosis (

p = 0.0411). No significant differences were observed for smoking, aerobic activity, strength exercise, or walking.

Time since diagnosis showed a significant positive association with current alcohol consumption (

Table 3). In the unadjusted model, patients who had been diagnosed more than three years prior had more than twice the odds of being current drinkers compared to those diagnosed within the past three years (OR = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.02–4.08). This association remained statistically significant even after adjusting for sex and age, with patients diagnosed more than three years ago having 2.32 times higher odds of current alcohol consumption compared to those diagnosed within the past three years (OR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.04–5.20).

3. Discussion

This study examines differences in health behaviors based on survival status and time since diagnosis among individuals with gastric or colorectal cancer using data from KNHANES (2014–2021). Among 478 participants diagnosed within the past 10 years, survivors were generally older and had a longer time since diagnosis than current patients. The prevalence of current alcohol consumption was significantly higher among survivors. Additionally, among patients, those diagnosed more than three years ago were more likely to report alcohol use. This association remained statistically significant after adjusting for sex and age. No significant differences were found for other health behaviors, including smoking, physical activity, and walking.

The mean age of the survivors was 66.5 years, which was higher than that of the patients, who had a mean age of 63.9 years. This finding is consistent with Baek’s (2018) study [

11], which used data from the KNHANES (2010–2015). In that study, the mean age of cancer patients was 61.8 years, while survivors had a mean age of 64.2 years [

11]. In East Asia, South Korea and Japan are the only countries that have implemented national gastric cancer screening programs without an upper age limit [

12]. The higher mean age of the participants in this study may reflect both increased life expectancy and widespread participation in national screening programs. As a result, the incidence of gastric and colorectal cancers has risen among older adults, and the relatively higher survival rates associated with these cancers may further contribute to this trend [

13,

14]. The average time since diagnosis was 2.6 years among current patients and 6.22 years among survivors. Given that the average disease duration for gastrointestinal cancers in South Korea has been reported as 2.58 years [

15], this difference may reflect heterogeneity in the timing of diagnosis and treatment trajectories. However, because disease duration can vary by cancer type and stage, future research should explore these factors in more detail.

Regarding current alcohol consumption, 29.9% of the patient group reported drinking, compared to 49.2% of survivors. This percentage is higher than the 38.3% alcohol consumption rate found in a cohort study on risky lifestyle behaviors among gastric cancer survivors [

16], but lower than the 52.6% reported in Baek’s (2018) study [

11]. In a large-scale cohort of Korean adults, 27.6% of all cancer survivors reported current alcohol consumption, with no significant differences observed according to family history of cancer [

17]. The difference in alcohol consumption rates between patients and survivors is consistent with prior research suggesting a gradual decline in adherence to healthy behaviors over time following diagnosis [

11]. This may indicate that while patients initially reduce alcohol intake after diagnosis, survivors tend to resume drinking as their sense of vulnerability diminishes. Given that alcohol consumption is a known risk factor for both primary cancer recurrence and the development of secondary cancers, this issue warrants further attention [

18]. The IARC has classified alcohol as a Group 1 carcinogen [

19]. Reflecting this, South Korea’s National Cancer Prevention Guidelines have strengthened their recommendations, shifting from advising “limiting alcohol intake to two drinks per day” to “avoiding alcohol consumption entirely” [

20]. However, the permissive drinking culture and social norms in South Korea may significantly influence drinking behaviors, highlighting the need for targeted intervention strategies. The high proportion of current drinkers among survivors in this study suggests that initial behavior changes may not be sustained without continued support. Therefore, active interventions and community-level management are essential for cancer survivors. In South Korea, a regional hub-based Cancer Survivor Integrated Support Center connects tertiary hospitals with local communities [

21]. This system should be leveraged more effectively to provide structured, personalized education and behavioral counseling. Furthermore, establishing long-term survivorship care programs is essential for sustaining and enhancing the quality of life of cancer survivors.

Among patients, those diagnosed more than three years earlier had a significantly higher drinking rate (40.9%) than those diagnosed within three years (25.4%). Additionally, the odds of current alcohol use were 2.32 times higher in the >3-year group. This finding aligns with previous studies [

22], which reported an initial decline in alcohol use within three months after diagnosis, followed by a gradual increase beginning around 12 months. Alcohol consumption is influenced by various demographic and psychological factors [

18]. Although patients may initially abstain from alcohol during treatment, factors such as stress, reduced social support, and the desire to return to normal life may lead to resumed drinking [

23]. Furthermore, existing education for gastric or colorectal cancer patients tends to focus more on dietary management, with relatively limited attention given to alcohol abstinence [

24]. Notably, alcohol not only contributes to cancer progression and recurrence but also impairs liver function and weakens the immune system, ultimately worsening treatment outcomes and survival rates [

18,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Despite these risks, maintaining long-term abstinence remains a challenge, particularly beyond the three-year mark. This suggests that the period of three years post-diagnosis may represent a critical transition point in alcohol-related health behaviors. To prevent increased alcohol consumption beyond this point, long-term survivorship care should incorporate regular counseling, lifestyle monitoring, and behavioral interventions. Effective strategies include continuous education about alcohol risks, personalized guidance on the benefits of abstinence for quality of life, and programs designed to enhance self-efficacy [

29]. Self-management support tools can empower survivors to regulate their behaviors, while collaboration with community resources helps sustain these efforts. To implement such programs effectively, stronger partnerships are needed among public health centers, cancer care institutions, and patient support organizations. The healthcare system should also emphasize the role of primary care and community-based services. Training specialized personnel to deliver tailored counseling and developing standardized educational modules will further improve patient health literacy. Through these coordinated efforts, a sustainable and collaborative model for managing alcohol use in cancer survivorship can be established, ultimately improving patients’ quality of life and reducing long-term health risks.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the KNHANES data, causal relationships between time since diagnosis and health behaviors cannot be established. However, by focusing on a clearly defined population and comparing subgroups by time since diagnosis, the study provides meaningful insights into behavioral patterns over time. Second, cancer diagnosis and health behavior data were self-reported, which may introduce recall or reporting bias. However, the KNHANES employs trained interviewers, validated questionnaires, and standardized procedures, which help minimize measurement error and improve data quality despite the subjective nature of responses. Third, the dataset lacked clinical information such as cancer stage, treatment type, or recurrence status, which could influence health behaviors and serve as potential confounders. While these limitations are inherent to large-scale population-based surveys, the study’s strengths—including its nationally representative sample and application of complex sampling weights—help mitigate concerns about validity and enhance generalizability of the findings. Fourth, although the KNHANES includes rich dietary information, this study intentionally focused on core behavioral factors—smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity—that are widely prioritized in cancer survivorship care. Nutrition, including specific dietary patterns, nutrient intake, and inflammatory potential, constitutes a complex domain that warrants an independent study design and analytical framework. Fifth, due to limited sample size, we could not conduct separate analyses for gastric and colorectal cancer. Although these cancers may differ in etiology, risk factors, and survivorship behaviors, stratified analyses would have reduced statistical power and generalizability. Future studies should utilize larger, cancer-type-specific datasets to explore these differences in greater detail.

Despite these limitations, the study has important strengths. It uses nationally representative data with complex sample weighting, allowing for generalizability of the Korean adult population. Additionally, by focusing on gastric and colorectal cancer, which are the two major gastrointestinal cancers with a relatively high burden and particular relevance in East Asia, this study provides evidence specific to the regional context and contributes to the development of tailored public health strategies and survivorship care planning.

This study highlights differences in alcohol consumption among gastric and colorectal cancer patients based on survival status and time since diagnosis. The findings suggest that as time since diagnosis increases, adherence to healthy behaviors such as alcohol restriction may decline, underscoring the need for continuous behavioral support in cancer survivorship care.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

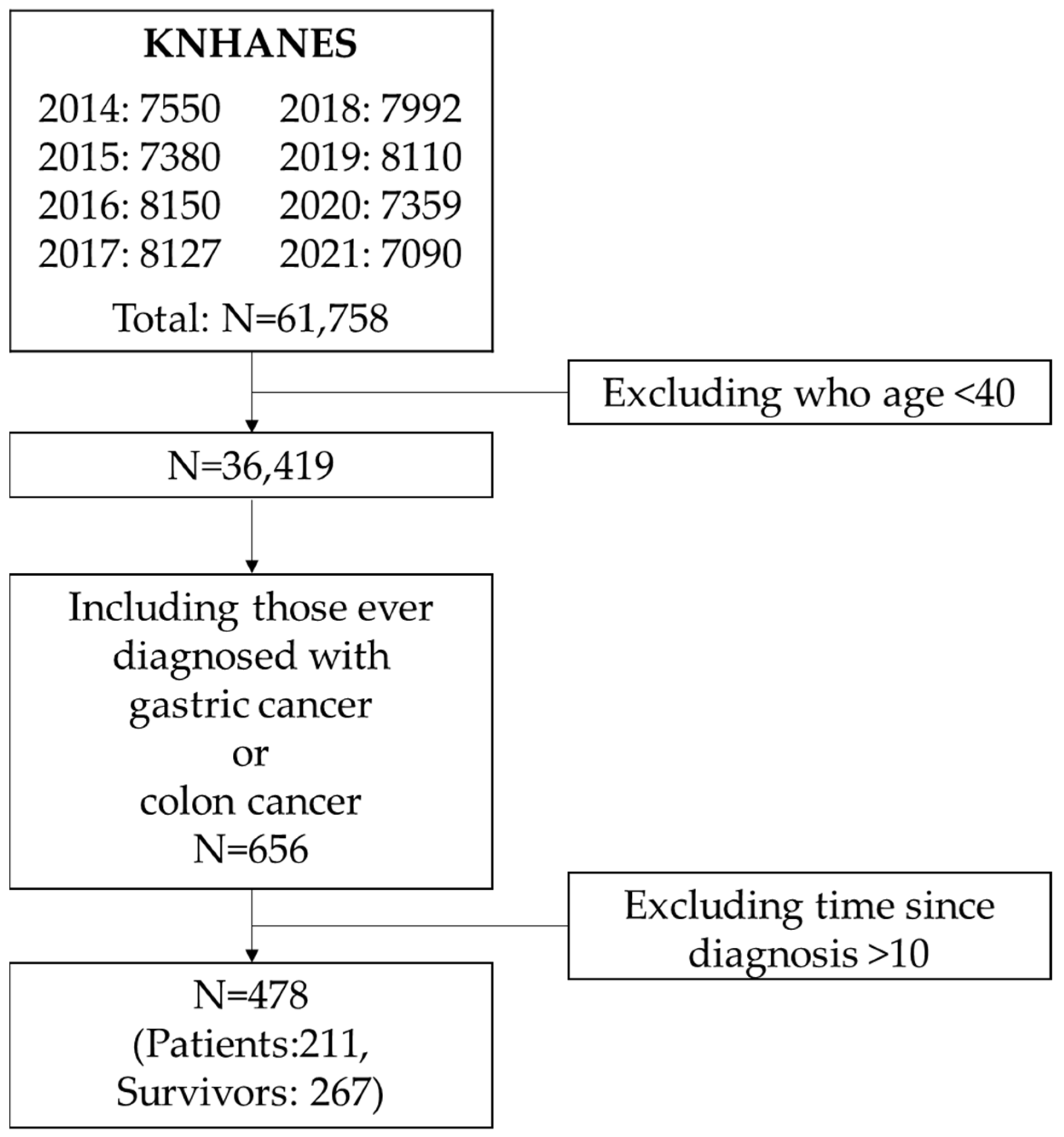

This study utilizes data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) collected between 2014 and 2021. KNHANES is a nationally representative health and nutrition survey conducted annually by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Although the survey has been conducted since 1998 and data are available through 2023, variables related to the diagnosis of gastric and colorectal cancer were only available through 2021. Additionally, to ensure consistency in the assessment of physical activity, we included data collected between 2014 and 2021, as the survey transitioned from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire to the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire in 2014. From the combined datasets between 2014 and 2021, a total of 61,758 individuals were identified. To exclude potential early-onset cancer cases, we limited the sample to adults aged 40 years or older, yielding 36,419 participants. Among them, 656 individuals reported having been diagnosed with gastric or colorectal cancer. Since individuals with more than 10 years of time since diagnosis are often considered cured or long-term survivors (

Supplementary Table S1), we restricted the final analytic sample to those with ≤10 years of time since diagnosis. As a result, 478 participants were included in the final analysis (

Figure 1).

4.2. Definition of Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients and Survivors

In the KNHANES, the health interview includes a section on disease history, where participants are asked whether they have ever been diagnosed by a physician with any of the following cancers: gastric, liver, colorectal, breast, cervical, lung, thyroid, or other cancers (a total of eight categories). Among these, gastric and colorectal cancers—both directly related to the gastrointestinal system—were selected as the primary outcome variables for this study.

Participants who reported having been diagnosed with gastric or colorectal cancer were additionally asked about their age at the time of diagnosis and whether they currently have the condition. Based on their responses to the current disease status question, individuals who answered “yes” were classified as patients, and those who answered “no” were classified as survivors.

4.3. Time Since Diagnosis

For participants who reported having been diagnosed with gastric or colorectal cancer, the age at the time of diagnosis was obtained through the survey. Time since diagnosis was calculated by subtracting the age at diagnosis from the participant’s current age. Based on the distribution of time since diagnosis among patients, this variable was categorized into the following two groups: ≤3 years and >3 years.

4.4. Health Behaviors

To examine differences in health behaviors by cancer recovery status and time since diagnosis, we utilized information on lifestyle factors.

Smoking status was determined using the following two survey items: lifetime smoking experience (categorized as fewer than 100 cigarettes, 100 or more cigarettes, and never smoked) and current smoking status (categorized as daily smoker, occasional smoker, former smoker, and non-smoker). Based on these responses, current smoking was redefined for this study. Participants who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, and reported that they were currently smoking daily, were classified as current smokers in accordance with the operational definitions provided in the KNHANES guideline. This binary classification aligns with public health standards but may limit nuance in dose–response associations.

Alcohol consumption was assessed based on lifetime drinking experience and alcohol use during the past year. Individuals who reported a history of alcohol consumption and indicated drinking at least once per month in response to the question about alcohol use in the past year were categorized as current drinkers. This definition, based on drinking frequency (≥once/month), follows KNHANES guidelines but does not include information on quantity (e.g., grams of alcohol), which is a limitation of the available data.

Physical activity was measured using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire, which collects information on moderate and vigorous intensity physical activity related to work and leisure, including the number of days per week and average duration per day. In addition, physical activity related to movement between places was assessed based on the number of days and the average daily time spent walking or cycling for transportation. Participants were classified as engaging in aerobic physical activity if they met any of the following criteria: at least 150 min of moderate intensity activity per week, at least 75 min of vigorous intensity activity per week, or an equivalent combination of both. These cutoffs are based on WHO and GPAQ standards for sufficient physical activity but do not capture specific exercise types or session-based frequency due to the structure of available data.

Muscle-strengthening activity was assessed by asking about the number of days in the past week the participant performed strength exercises such as push-ups, sit-ups, dumbbell or barbell training, or pull-ups. Individuals who engaged in such activities on two or more days per week were classified as performing strength exercise. Although participants were asked about weekly frequency, the KNHANES does not collect details about intensity or duration per session for strength exercise. Therefore, the binary classification of ≥2 days/week was applied per the KNHANES guidelines.

Walking activity was assessed based on whether the participant walked in the past week, how many days they walked, and the average daily duration. Participants who walked for at least 30 min per session on five or more days per week were categorized as engaging in sufficient walking. This classification is consistent with physical activity guidelines.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

As the KNHANES is based on a nationally representative sample, all analyses were conducted using sample weights to account for the complex survey design. Continuous variables were summarized as weighted means and standard errors (SEs), while categorical variables were presented as weighted percentages and SEs. Differences in continuous variables were assessed using weighted t-tests, and differences in categorical variables were examined using the Rao–Scott chi-square test, both of which account for complex sampling. To evaluate the association between time since diagnosis and each health behavior, weighted logistic regression analyses were performed, and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).