Associations Between Sleep Patterns, Circadian Preference, and Anxiety and Depression: A Two-Year Prospective Study Among Norwegian Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sleep Patterns, Circadian Preference, and Social Jetlag as Longitudinal Predictors of Anxiety and Depression

Adjusted Analyses

2.2. Anxiety/Depression as Predictors of Sleep Duration, Insomnia, and Circadian Preference

3. Discussion

3.1. Implications

3.2. Strengths and Limitations

4. Methods and Materials

4.1. Instruments

4.1.1. Sleep Duration and Social Jetlag

4.1.2. Circadian Preference

4.1.3. Insomnia

4.1.4. Anxiety

4.1.5. Depression

4.2. Ethics

4.3. Demographics

4.4. Statistical Analyses

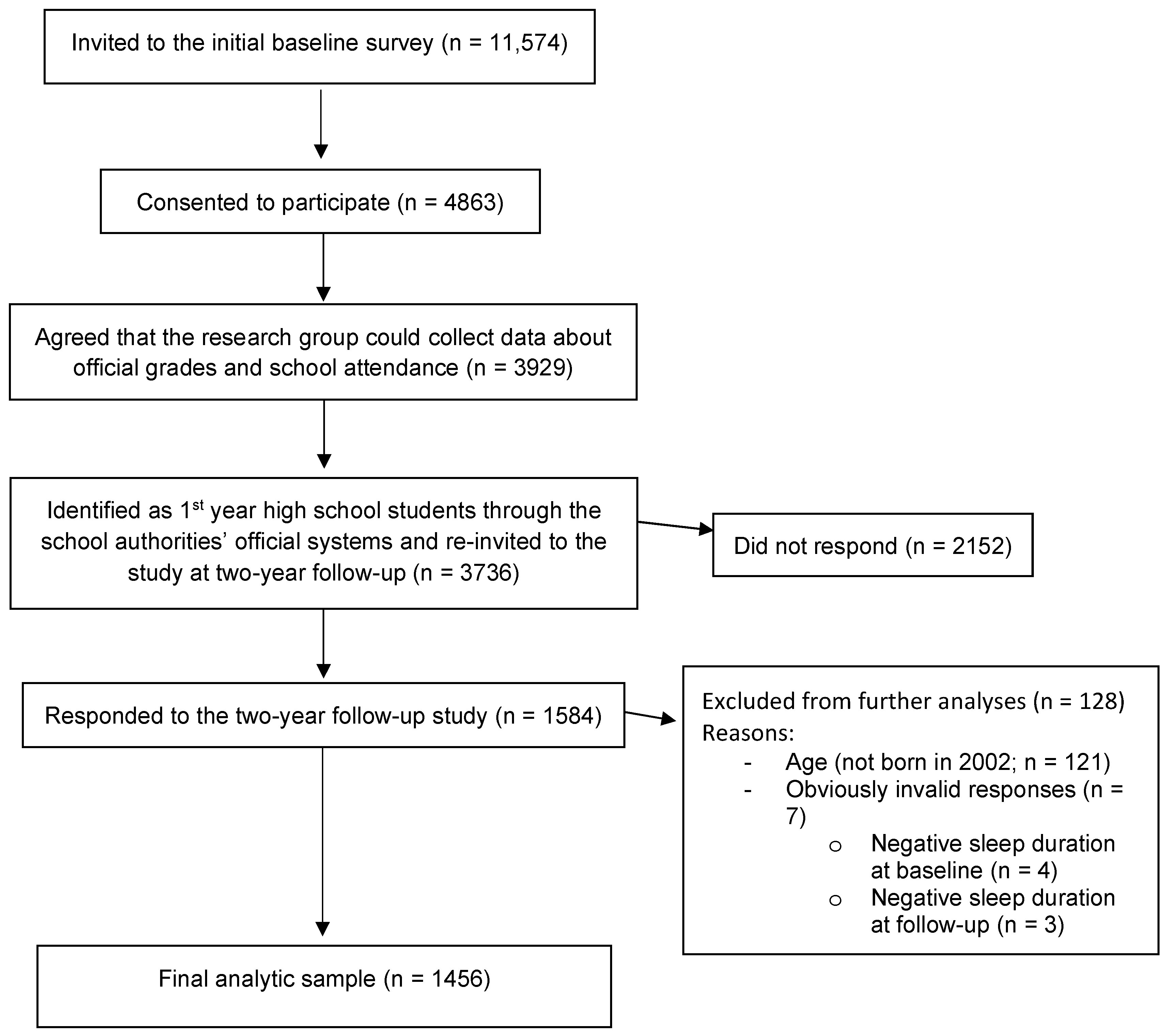

4.5. Participant Flow

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIS | Bergen Insomnia Scale |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| rMEQ | The reduced Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire |

| WASO | Wake after sleep onset |

References

- Dahl, R.E.; Allen, N.B.; Wilbrecht, L.; Suleiman, A.B. Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature 2018, 554, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, T.; Keshavan, M.; Giedd, J.N. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, T.; Gaspar, T.; Matos, M.G. Sleep deprivation in adolescents: Correlations with health complaints and health-related quality of life. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, M.G.; Gaspar, T.; Tomé, G.; Paiva, T. Sleep variability and fatigue in adolescents: Associations with school-related features. Int. J. Psychol. 2016, 51, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradisar, M.; Gardner, G.; Dohnt, H. Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: A review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, G.; Danna, S.; Gobiņa, I.; Rasmussen, M.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Tynjälä, J.; Janssen, I.P.; Kalman, M.P.; Villeruša, A.; Husarova, D.; et al. How Are Adolescents Sleeping? Adolescent Sleep Patterns and Sociodemographic Differences in 24 European and North American Countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S81–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, N.; MacQueen, G. Adolescence as a unique developmental period. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysing, M.; Sivertsen, B.; Nilsen, S.A.; Heradstveit, O.; Bøe, T.; Askeland, K.G. Sleep and dropout from upper secondary school: A register-linked study. Sleep Health 2023, 9, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askeland, K.G.; Bøe, T.; Sivertsen, B.; Linton, S.J.; Heradstveit, O.; Nilsen, S.A.; Hysing, M. Association of Depressive Symptoms in Late Adolescence and School Dropout. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Krizan, Z.; Hisler, G. Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among U.S. adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med. 2017, 39, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.J.; Wolfson, A.R.; Tarokh, L.; Carskadon, M.A. An update on adolescent sleep: New evidence informing the perfect storm model. J. Adolesc. 2018, 67, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carskadon, M.A. Sleep in adolescents: The perfect storm. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 58, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Ricken, J.; Havel, M.; Guth, A.; Merrow, M. A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R1038–R1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, T.; Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Ip, P.S.; Fowle, J.; Buckhalt, J. School Start Times, Sleep, and Youth Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021054068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan-Lopez, P.; Domínguez, R.; Gísladóttir, T.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Pihu, M.; Ries, F.; Klonizakis, M. Sleep Quality and Duration in European Adolescents (The AdolesHealth Study): A Cross-Sectional, Quantitative Study. Children 2021, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Adams Hillard, P.J.; Katz, E.S.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: Final report. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxvig, I.W.; Bjorvatn, B.; Hysing, M.; Sivertsen, B.; Gradisar, M.; Pallesen, S. Sleep in older adolescents. Results from a large cross-sectional, population-based study. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, G.M.; Li, X.; Hale, L.; Chang, A.M. Sleep duration and social jetlag are independently associated with anxious symptoms in adolescents. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 36, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.A.; Roveda, E.; Montaruli, A.; Galasso, L.; Weydahl, A.; Caumo, A.; Carandente, F. Chronotype influences activity circadian rhythm and sleep: Differences in sleep quality between weekdays and weekend. Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxvig, I.W.; Evanger, L.N.; Pallesen, S.; Hysing, M.; Sivertsen, B.; Gradisar, M.; Bjorvatn, B. Circadian typology and implications for adolescent sleep health. Results from a large, cross-sectional, school-based study. Sleep Med. 2021, 83, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, S.E.M.; Brady, E.M.; Robertson, N. Associations between social jetlag and mental health in young people: A systematic review. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 36, 1316–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, N.; Okamura, K. Longitudinal course and outcome of social jetlag in adolescents: A 1-year follow-up study of the adolescent sleep health epidemiological cohorts. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sateia, M.J. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- de Zambotti, M.; Goldstone, A.; Colrain, I.M.; Baker, F.C. Insomnia disorder in adolescence: Diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 39, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Espie, C.A.; Altena, E.; Arnardottir, E.S.; Baglioni, C.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Bastien, C.; Berzina, N.; Bjorvatn, B.; Dikeos, D.; et al. The European Insomnia Guideline: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorvatn, B.; Jernelöv, S.; Pallesen, S. Insomnia—A Heterogenic Disorder Often Comorbid With Psychological and Somatic Disorders and Diseases: A Narrative Review With Focus on Diagnostic and Treatment Challenges. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 639198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, E.; Buysse, D.J. Insomnia: Prevalence, Impact, Pathogenesis, Differential Diagnosis, and Evaluation. Sleep Med. Clin. 2008, 3, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.O.; Roth, T.; Schultz, L.; Breslau, N. Epidemiology of DSM-IV insomnia in adolescence: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity, and an emergent gender difference. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e247–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Bélanger, L.; LeBlanc, M.; Ivers, H.; Savard, J.; Espie, C.A.; Mérette, C.; Baillargeon, L.; Grégoire, J.P. The natural history of insomnia: A population-based 3-year longitudinal study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, D.; Kiss, O.; Prouty, D.E.; Baker, F.C.; de Zambotti, M. Clinical characterization of insomnia in adolescents—An integrated approach to psychopathology. Sleep Med. 2022, 93, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.G. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 869–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.; Zhang, J.; Lamers, F.; Taylor, A.D.; Hickie, I.B.; Merikangas, K.R. Health correlates of insomnia symptoms and comorbid mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. Sleep 2015, 38, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, V.; Gnazzo, M.; Rapelli, G.; Marchi, M.; Pingani, L.; Ferrari, S.; De Ronchi, D.; Varallo, G.; Starace, F.; Franceschini, C.; et al. Association between sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1341686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, H.M.; Alrowais, N.A.; Bin-Saad, N.S.; Al-Subaie, N.M.; Haji, A.M.; Alhaqwi, A.I. Sleep disorder among medical students: Relationship to their academic performance. Med. Teach. 2012, 34 (Suppl. 1), S37–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.G. Insomnia: Symptom or diagnosis? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 1037–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacaro, V.; Miletic, K.; Crocetti, E. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies on the interplay between sleep, mental health, and positive well-being in adolescents. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2024, 24, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, P.K.; Roberts, R.M.; Harris, J.K. A Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. Sleep 2013, 36, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Tu, S.; Sheng, J.; Shao, A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2324–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmandakh, A.; Roest, A.M.; Jonge, P.; Oldehinkel, A.J. The bidirectional association between sleep problems and anxiety symptoms in adolescents: A TRAILS report. Sleep Med. 2020, 67, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraden, D.A.; Mullin, B.C.; Hankin, B.L. The relationship between depression and chronotype: A longitudinal assessment during childhood and adolescence. Depress. Anxiety 2017, 34, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, P.K.; Roberts, R.M.; Harris, J.K.; Bruni, O. The direction of the relationship between symptoms of insomnia and psychiatric disorders in adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ru, T.; Niu, J.; He, M.; Zhou, G. How does the COVID-19 affect mental health and sleep among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal follow-up study. Sleep Med. 2021, 85, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusdottir, S.; Magnusdottir, I.; Gunnlaugsdottir, A.K.; Hilmisson, H.; Hrolfsdottir, L.; Paed, A. Sleep duration and social jetlag in healthy adolescents. Association with anxiety, depression, and chronotype: A pilot study. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, L.; Copeland, W.E.; Angold, A.; Bondy, C.L.; Costello, E.J. Sleep problems predict and are predicted by generalized anxiety/depression and oppositional defiant disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 53, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradisar, M.; Kahn, M.; Micic, G.; Short, M.; Reynolds, C.; Orchard, F.; Bauducco, S.; Bartel, K.; Richardson, C. Sleep’s role in the development and resolution of adolescent depression. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacaro, V.; Carpentier, L.; Crocetti, E. Sleep Well, Study Well: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies on the Interplay between Sleep and School Experience in Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.O.; Roth, T.; Breslau, N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: Exploration of the direction of risk. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2006, 40, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnesen, I.B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Pallesen, S.; Waage, S.; Gradisar, M.; Wilhelmsen-Langeland, A.; Saxvig, I.W. Insomnia in adolescent epidemiological studies: To what extent can the symptoms be explained by circadian factors? Chronobiol. Int. 2025, 42, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallestad, H.; Hansen, B.; Langsrud, K.; Ruud, T.; Morken, G.; Stiles, T.C.; Gråwe, R.W. Differences between patients’ and clinicians’ report of sleep disturbance: A field study in mental health care in Norway. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannotti, F.; Cortesi, F.; Sebastiani, T.; Ottaviano, S. Circadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescence. J. Sleep Res. 2002, 11, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C. Age and Gender Differences in Morningness–Eveningness During Adolescence. J. Genet. Psychol. 2011, 172, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J.M.; Moyer, A. Effects of school start time on students’ sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, and attendance: A meta-analysis. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askeland, K.G.; Bøe, T.; Lundervold, A.J.; Stormark, K.M.; Hysing, M. The Association Between Symptoms of Depression and School Absence in a Population-Based Study of Late Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finning, K.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ford, T.; Danielson-Waters, E.; Shaw, L.; Romero De Jager, I.; Stentiford, L.; Moore, D.A. Review: The association between anxiety and poor attendance at school—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 24, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, K.; Sakarya, A.; Jansson-Fröjmark, M. The reduced Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and related factors in a young Swedish population. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 36, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Merrow, M. Life between clocks: Daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2003, 18, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adan, A.; Almirall, H. Horne & Östberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire: A reduced scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.A.; Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pallesen, S.; Bjorvatn, B.; Nordhus, I.H.; Sivertsen, B.; Hjørnevik, M.; Morin, C.M. A new scale for measuring insomnia: The Bergen Insomnia Scale. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2008, 107, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, T.; Ergun, A. Validity and reliability of Bergen Insomnia Scale (BIS) among adolescents. Clin. Exp. Health Sci. 2018, 8, 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattmyr, M.; Lindberg, M.S.; Solem, S.; Hjemdal, O.; Havnen, A. Factor structure, measurement invariance, and concurrent validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale-7 in a Norwegian psychiatric outpatient sample. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdzovic Andreas, J.; Brunborg, G.S. Depressive Symptomatology among Norwegian Adolescent Boys and Girls: The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) Psychometric Properties and Correlates. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisting, L.; Johnson, S.U.; Bulik, C.M.; Andreassen, O.A.; Rø, Ø.; Bang, L. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) in a large female sample of adults with and without eating disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Percentage | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Girl | 61.4% | 894 |

| Boy | 38.6% | 562 |

| Age | ||

| 16 years | 64.3 | 936 |

| 17 years | 35.7 | 520 |

| Maternal educational level | ||

| Junior high, high school or similar | 3.8% | 56 |

| High school | 18.7% | 272 |

| Higher education, <4 years | 22.2% | 323 |

| Higher education, ≥4 years | 40.7% | 593 |

| Don’t know | 14.6% | 212 |

| Paternal educational level | ||

| Junior high, high school or similar | 5.3% | 77 |

| High school | 25.1% | 365 |

| Higher education, <4 years | 17.1% | 249 |

| Higher education, ≥4 years | 34.1% | 497 |

| Don’t know | 18.4% | 268 |

| Average units of caffeine per day | ||

| None | 43.8% | 600 |

| One | 34.8% | 476 |

| Two | 12.6% | 172 |

| Three or more | 8.8% | 121 |

| Use of prescribed sleep medications | ||

| Never | 96.4% | 1350 |

| Less than weekly | 1.1% | 15 |

| Weekly | 0.8% | 11 |

| Daily | 1.7% | 24 |

| Descriptive Statistics | T Tests * | McNemar’s | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-Up | Mean Difference (SE Mean) | 95% CI [Lower, Upper] | T | Test Statistics | ||

| Sleep patterns and insomnia | |||||||

| Sleep duration, school nights, hh:mm (SD) | 6:49 (81 min) | 6:55 (77 min) | −5.80 (2.29) | [−10.27, −1.29] | −2.52 | 0.012 a | |

| Sleep duration, free nights, hh:mm (SD) | 8:37 (94 min) | 8:35 (79 min) | 0.663 (2.59) | [−4.42, 5.75] | 0.26 | 0.798 a | |

| Social jetlag, hh:mm (SD) | 2:36 (62 min) | 2:28 (68 min) | 7.73 (1.76) | [4.27, 11.19) | 4.38 | <0.001 a | |

| Social jetlag ≥ 2 hours (%) | 73.9% | 67.6% | 16,687 | <0.001 b | |||

| BIS, total score (M, SD) | 12.0 (7.9) | 12.9 (8.3) | −0.92 (0.23) | [−1.37, −0.48] | −4.09 | <0.001 a | |

| Chronic insomnia cases(%) | 33.0% | 35.4% | 2267 | <0.132 b | |||

| Depression | |||||||

| PHQ-9 (M, SD) | 7.4 (5.5) | 8.6 (6.0) | −1.24 (0.15) | [−1.52, −0.95] | −8.44 | <0.001 a | |

| PHQ-9 above cut-off (%) | 27.8% | 35.9% | 35,565 | <0.001 b | |||

| Anxiety | |||||||

| GAD-7 (M, SD) | 5.8 (4.7) | 6.4 (5.2) | −0.66 (0.13) | [−0.91, −0.40) | −4.98 | <0.001 a | |

| GAD-7, above cut-off (%) | 27.6% | 33.5% | 19,563 | <0.001 b | |||

| Circadian preference | |||||||

| MEQr, sum (M, SD) | 12.9 (3.3) | 13.2 (3.4) | −0.26 (0.07) | [−0.41, −0.12] | −3.54 | <0.001 a | |

| MEQr, categorical (%) | |||||||

| Morning type | 9.7% | 11.4% | |||||

| Intermediate type | 53.0% | 55.7% | |||||

| Evening type | 37.3% | 32.9% | |||||

| Adjusted for Baseline Anxiety/Depression | Additional Adjustment for Sex and Maternal Education | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Anxiety | Anxiety | |

| Sleep duration (hours), school nights | 0.84 (0.77, 0.93) | 0.87 (0.78, 0.96) |

| Sleep duration (hours), free nights | 0.93 (0.86, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) |

| Chronic insomnia | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.86 (1.43, 2.43) | 1.92 (1.41, 2.62) |

| Insomnia symptoms | 1.06 (1.04, 1.08) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.09) |

| Circadian preference, continuous | 0.965 (0.928, 1.004) | 0.955 (0.914, 0.999) |

| Circadian preference, categorical | ||

| Morning | 0.85 (0.57, 1.26) | 0.77 (0.49, 1.21) |

| Intermediate | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Evening | 1.12 (0.87, 1.44) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.51) |

| Social jetlag, minutes | 1.001 (0.998, 1.003) | 1.000 (0.998, 1.003) |

| Social jetlag ≥ 2 h | ||

| <2 h | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥2 h | 0.98 (0.74, 1.31) | 0.95 (0.69, 1.30) |

| Depression | Depression | |

| Sleep duration (hours), school nights | 0.82 (0.75, 0.89) | 0.81 (0.73, 0.89) |

| Sleep duration (hours), free nights | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) |

| Chronic insomnia | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.82 (1.36, 2.44) | 2.02 (1.46, 2.78) |

| Insomnia symptoms | 1.07 (1.05, 1.09) | 1.07 (1.05, 1.09) |

| Circadian preference, continuous | 0.949 (0.914, 0.986) | 0.943 (0.905, 0.984) |

| Circadian preference, categorical | ||

| Morning | 0.80 (0.52, 1.23) | 0.93 (0.60, 1.44) |

| Intermediate | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Evening | 1.33 (0.998, 1.76) | 1.42 (1.05, 1.94) |

| Social jetlag, minutes | 1.001 (0.999, 1.003) | 1.001 (0.999, 1.003) |

| Social jetlag ≥ 2 h | ||

| <2 h | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| ≥2 h | 1.04 (0.77, 1.40) | 1.04 (0.75, 1.43) |

| Adjusted for Corresponding Sleep Parameter at Baseline | Additional Adjustment for Sex and Maternal Education | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Sleep duration ≥ 8 h, school nights | Sleep duration ≥ 8 h, school nights | |

| Anxiety | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.94 (0.67, 1.32) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.35) |

| Depression | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.82 (0.57, 1.18) | 0.81 (0.54, 1.23) |

| Sleep duration ≥ 8 h, free nights | Sleep duration ≥ 8 h, free nights | |

| Anxiety | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.94 (0.71, 1.26) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.28) |

| Depression | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.93 (0.70, 1.25) | 0.88 (0.64, 1.21) |

| Chronic insomnia | Chronic insomnia | |

| Anxiety | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.91 (1.46, 2.49) | 1.84 (1.37, 2.48) |

| Depression | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 2.00 (1.52, 2.64) | 1.74 (1.27, 2.38) |

| Evening preference | Evening preference | |

| Anxiety | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.25 (0.93, 1.69) | 1.30 (0.94, 1.79) |

| Depression | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 1.43 (1.05, 1.94) | 1.40 (1.01, 1.96) |

| Social jetlag ≥ 2 h | Social jetlag ≥ 2 h | |

| Anxiety | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.69 (0.53, 0.91) | 0.74 (0.55, 0.997) |

| Depression | ||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Yes | 0.69 (0.52, 0.92) | 0.66 (0.48, 0.90) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Evanger, L.N.; Saxvig, I.W.; Pallesen, S.; Gradisar, M.; Lie, S.A.; Bjorvatn, B. Associations Between Sleep Patterns, Circadian Preference, and Anxiety and Depression: A Two-Year Prospective Study Among Norwegian Adolescents. Clocks & Sleep 2025, 7, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020026

Evanger LN, Saxvig IW, Pallesen S, Gradisar M, Lie SA, Bjorvatn B. Associations Between Sleep Patterns, Circadian Preference, and Anxiety and Depression: A Two-Year Prospective Study Among Norwegian Adolescents. Clocks & Sleep. 2025; 7(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleEvanger, Linn Nyjordet, Ingvild West Saxvig, Ståle Pallesen, Michael Gradisar, Stein Atle Lie, and Bjørn Bjorvatn. 2025. "Associations Between Sleep Patterns, Circadian Preference, and Anxiety and Depression: A Two-Year Prospective Study Among Norwegian Adolescents" Clocks & Sleep 7, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020026

APA StyleEvanger, L. N., Saxvig, I. W., Pallesen, S., Gradisar, M., Lie, S. A., & Bjorvatn, B. (2025). Associations Between Sleep Patterns, Circadian Preference, and Anxiety and Depression: A Two-Year Prospective Study Among Norwegian Adolescents. Clocks & Sleep, 7(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7020026