Association of Insomnia with Functional Outcomes Relevant to Daily Behaviors and Sleep-Related Quality of Life among First Nations People in Two Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

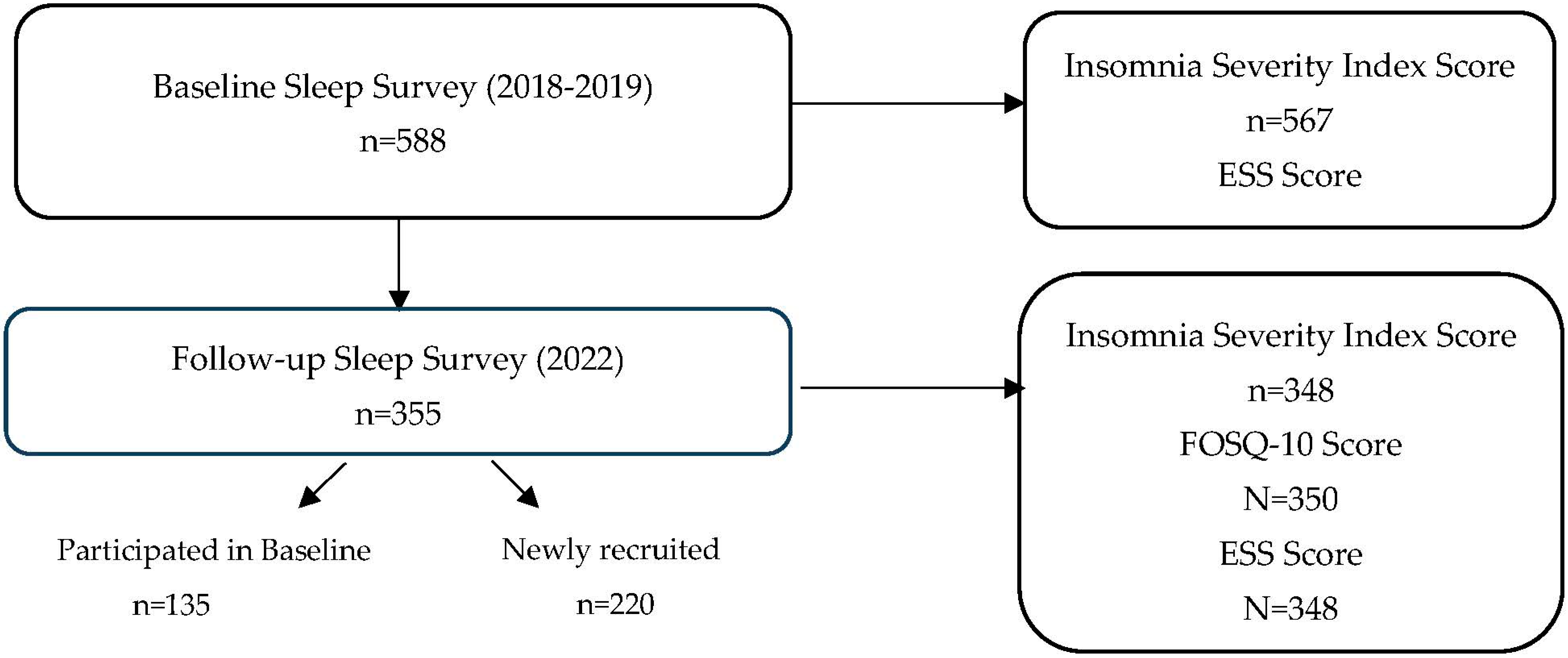

4.1. Study Sample

4.2. Data Collection

4.2.1. Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

4.2.2. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)

4.2.3. FOSQ-10 Questionnaire

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOSQ | Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire |

| FNSHP | First Nations Sleep Health Project |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| ISI | Insomnia Severity Index |

| ESS | Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

References

- Sutton, D.A.; Moldofsky, H.; Badley, E.M. Insomnia and health problems in Canadians. Sleep 2001, 24, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjepkema, M. Insomnia. Health Rep. 2005, 17, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; LeBlanc, M.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H.; Mérette, C.; Savard, J. Prevalence of insomnia and its treatment in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Yau, J.; Rao, D.P.; Morin, C.M. Prevalence of insomnia for Canadians aged 6 to 79. Health Rep. 2018, 29, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Blais, F.C.; Morin, C.M.; Boisclair, A.; Grenier, V.; Guay, B. L’insomnie Prévalence et traitement chez les patients consultant enmédecine générale Insomnia. Prevalence and treatment of patients in general practice. Can. Fam. Physician 2001, 47, 759–767. [Google Scholar]

- Chaput, J.P.; Janssen, I.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Carney, C.E.; Dang-Vu, T.T.; Davidson, J.R.; Robillard, R.; Morin, C.M. Economic burden of insomnia symptoms in Canada. Sleep Health 2023, 9, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosman, J.A.; Karunanayake, C.P.; Fenton, M.; Ramsden, V.R.; Skomro, R.; Kirychuk, S.; Rennie, D.C.; Seeseequasis, J.; Bird, C.; McMullin, K.; et al. Prevalence of Insomnia in Two Saskatchewan First Nation Communities. Clocks Sleep 2021, 3, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, W.W.; Bagot, K.; Thomas, S.; Magakian, N.; Bedwani, D.; Larson, D.; Brownstein, A.; Zaky, C. Quality of life in patients suffering from insomnia. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, T.E.; Laizner, A.M.; Evans, L.K.; Maislin, G.; Chugh, D.K.; Lyon, K.; Smith, P.L.; Schwartz, A.R.; Redline, S.; Pack, A.I.; et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep 1997, 20, 835–843. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, A.; Baptista, P.; Ebner, E.M.; Jeschke, S.; König, I.R.; Bruchhage, K.L. Insomnia affects patient-reported outcome in sleep apnea treated with hypoglossal nerve stimulation. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.N.; Zong, Q.Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, Y.F.; Ng, C.H.; Chen, L.G.; Xiang, Y.T. Gender Difference in the Prevalence of Insomnia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 577429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, J.L.; Gras, C.B.; García, Y.D.; Lapeira, J.T.; del Campo del Campo, J.M.; Verdejo, M.A. Functional status in the elderly with insomnia. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccabella, A.; Malouf, J. How do sleep-related health problems affect functional status according to sex? J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Pien, G.W.; Weaver, T.E. Gender differences in the clinical manifestation of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowakowski, S.; Meers, J.; Heimbach, E. Sleep and Women’s Health. Sleep Med. Res. 2013, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laratta, C.R.; Ayas, N.T.; Povitz, M.; Pendharkar, S.R. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. CMAJ 2017, 189, E1481–E1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjafield, A.V.; Ayas, N.T.; Eastwood, P.R.; Heinzer, R.; Ip, M.S.M.; Morrell, M.J.; Nunez, C.M.; Patel, S.R.; Penzel, T.; Pépin, J.L.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: A literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.H.; Le, A.; Funk-White, M.; Palamar, J.J. Cannabis and Prescription Drug Use Among Older Adults with Functional Impairment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Hillard, P.J.A.; Katz, E.S.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: Final report. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanayake, C.P.; Fenton, M.; Skomro, R.; Ramsden, V.R.; Kirychuk, S.; Rennie, D.C.; Seeseequasis, J.; Bird, C.; McMullin, K.; Russell, B.P.; et al. Sleep Deprivation in two Saskatchewan First Nation Communities: A Public Health Consideration. Sleep Med. X 2021, 3, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Tri- Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2022. Available online: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2022_chapter9-chapitre9.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Morin, C.M. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C.H.; Áres, A.V.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H. The insomnia severity index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Thoracic Society. Sleep Related Questionnaires—Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ). 2024. Last Updated Feb 2023. Available online: https://www.thoracic.org/members/assemblies/assemblies/srn/questionaires/fosq.php (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Chasens, E.R.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Weaver, T.E. Development of the FOSQ-10: A short version of the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire. Sleep 2009, 32, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, T.E.; Maislin, G.; Dinges, D.F.; Bloxham, T.; George, C.F.; Greenberg, H.; Kader, G.; Mahowald, M.; Younger, J.; Pack, A.I. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep 2007, 30, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FOSQ 10 Subscale | Questions (Question #) | Possible Range | N | Mean ± SD | Range Min–Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Productivity | 1. Concentrating 2. Remembering | 1–4 | 340 | 3.25 ± 0.79 | 1–4 | |

| Activity Level | 6. Relations Affected 8. Activity in Morning 9. Activity in Evening | 1–4 | 343 | 3.37 ± 0.76 | 1–4 | |

| Vigilance | 3. Driving short distance 4. Driving long distance 7. Watching Movies | 1–4 | 329 | 3.54 ± 0.62 | 1–4 | |

| Social Outcomes | 5. Visit in their home | 1–4 | 313 | 3.60 ± 0.69 | 1–4 | |

| Intimacy and Sexual Relationships | 10. Desire intimacy | 1–4 | 281 | 3.52 ± 0.82 | 1–4 | |

| FOSQ 10 Total Score | 5–20 | 350 | 17.27 ± 2.98 | 5–20 | ||

| By Sex: | Male | 5–20 | 142 | 17.88 ± 2.68 | 6.5–20 | |

| Female | 5–20 | 208 | 16.85 ± 3.12 * | 5–20 | ||

| Variable | with Clinical Insomnia (ISI ≥ 15) Mean ± SD or n (%) | without Clinical Insomnia (ISI < 15) Mean ± SD or n (%) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | n = 73 | 39.63 ± 13.79 | N = 274 | 40.98 ± 14.91 | 0.485 |

| Sex | n = 73 | 53 (72.6%) females | N = 275 | 150 (54.5%) females | 0.005 |

| Weight in kg | n = 69 | 79.74 ± 18.79 | N = 261 | 82.19 ± 20.93 | 0.378 |

| Neck Circumference in cm | n = 55 | 37.87 ± 6.11 | N = 219 | 38.45 ± 5.23 | 0.474 |

| Body Mass Index—BMI (kg/m2) | n = 67 | 28.56 ± 6.92 | N = 259 | 28.75 ± 6.92 | 0.839 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) Score | n = 72 | 9.75 ± 5.27 | N = 273 | 6.05 ± 4.11 | <0.001 |

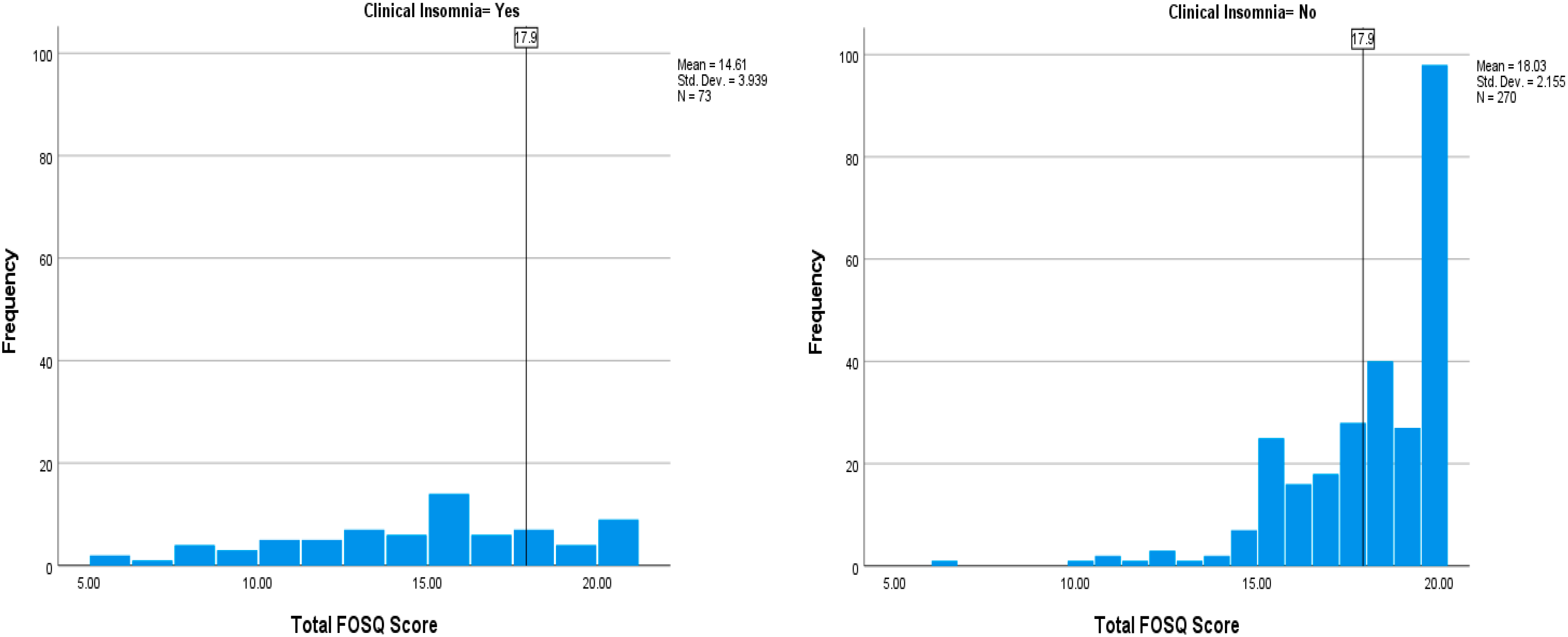

| FOSQ-10 Total Score | n = 73 | 14. 61 ± 3.94 | N = 270 | 18.03 ± 2.15 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Total # n (%) | Impaired (FOSQ 10 < 17.90) n (%) # | Not Impaired (FOSQ 10 ≥ 17.90) n (%) # | p Value * | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 350) | 163 (46.6) | 187 (53.4) | |||

| Sex (n = 350) | |||||

| Male | 142 (40.6) | 52 (31.9) | 90 (48.1) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Female | 208 (59.4) | 111 (68.1) | 97 (51.9) | 0.002 | 1.98 (1.28, 3.06) |

| Age, in years (Mean ± SD) (n = 349) | 40.76 ± 14.60 | 39.46 ± 14.54 | 41.89 ± 14.60 | 0.122 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) |

| Age group, in years (n = 349) | |||||

| 18–39 | 175 (50.1) | 85 (52.5) | 90 (48.1) | Ref | 1.00 |

| 40–49 | 67 (19.2) | 30 (18.5) | 37 (19.8) | 0.597 | 0.86 (0.49, 1.51) |

| 50–59 | 61 (17.5) | 28 (17.3) | 33 (17.6) | 0.719 | 0.90 (0.50, 1.61) |

| 60 and older | 46 (13.2) | 19 (11.7) | 27 (14.4) | 0.380 | 0.75 (0.39, 1.44) |

| Education Level (n = 341) | |||||

| High school not completed | 217 (63.6) | 108 (67.1) | 109 (60.6) | Ref | 1.00 |

| High school or above | 124 (36.4) | 53 (32.9) | 71 (39.4) | 0.212 | 0.75 (0.48, 1.17) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (n = 329) | |||||

| Neither overweight nor obese | 120 (36.5) | 57 (37.5) | 63 (35.6) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Overweight | 79 (24.0) | 37 (24.3) | 42 (23.7) | 0.927 | 0.97 (0.55, 1.72) |

| Obese | 130 (39.5) | 58 (38.2) | 72 (40.7) | 0.648 | 0.89 (0.54, 1.46) |

| Smoking status (n = 343) | |||||

| Never smoker | 64 (18.7) | 28 (17.4) | 36 (19.8) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Ex-smoker | 38 (11.1) | 23 (14.3) | 15 (8.2) | 0.103 | 1.97 (0.87, 4.46) |

| Current smoker | 241 (70.3) | 110 (68.3) | 131 (72.0) | 0.787 | 1.08 (0.62, 1.88) |

| Physical activity—at least three days per week (n = 306) | |||||

| No | 129 (42.2) | 68 (46.9) | 61 (37.9) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Yes | 177 (57.8) | 77 (53.1) | 100 (62.1) | 0.112 | 0.69 (0.44, 1.09) |

| Prescription medication use on a regular basis (n = 348) | |||||

| No | 207 (59.5) | 82 (50.3) | 125 (67.6) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Yes | 141 (40.5) | 81 (49.7) | 60 (32.4) | 0.001 | 2.06 (1.33, 3.18) |

| Clinical Insomnia (n = 343) | |||||

| No | 270 (78.7) | 103 (65.6) | 167 (89.8) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Yes | 73 (21.3) | 54 (34.4) | 19 (10.2) | <0.001 | 4.61 (2.59, 8.21) |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness (n = 343) | |||||

| Normal | 275 (80.2) | 118 (74.2) | 157 (85.3) | Ref | 1.00 |

| Abnormal | 68 (19.8) | 41 (25.8) | 27 (14.7) | 0.011 | 2.02 (1.18, 3.47) |

| Loud snoring (n = 344) | |||||

| No | 239 (69.5) | 103 (64.0) | 136 (74.3) | Ref | |

| Yes | 105 (30.5) | 58 (36.0) | 47 (25.7) | 0.038 | 1.63 (1.03, 2.59) |

| Hours of sleep (Mean ± SD), in hours (n = 301) | 8.03 ± 1.93 | 7.92 ± 2.07 | 8.11 ± 1.83 | 0.421 | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) |

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.00 | |

| Female | 1.69 (1.04, 2.75) | 0.033 |

| Age group, in years | ||

| 18–39 | 1.00 | |

| 40–49 | 0.62 (0.31, 1.21) | 0.159 |

| 50–59 | 0.59 (0.30, 1.17) | 0.130 |

| 60 and older | 0.48 (0.22, 1.06) | 0.068 |

| Prescription medication use on a regular basis | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 2.17 (1.27, 3.72) | 0.005 |

| Clinical Insomnia | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.51 (1.89, 6.52) | <0.001 |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | ||

| Normal | 1.00 | |

| Abnormal | 1.40 (0.76, 2.58) | 0.287 |

| Loud snoring | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.73 (1.03, 2.89) | 0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karunanayake, C.P.; Dosman, J.A.; Ayas, N.; Fenton, M.; Seeseequasis, J.; Lindain, R.; Seesequasis, W.; McMullin, K.; Kachroo, M.J.; Ramsden, V.R.; et al. Association of Insomnia with Functional Outcomes Relevant to Daily Behaviors and Sleep-Related Quality of Life among First Nations People in Two Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada. Clocks & Sleep 2024, 6, 578-588. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep6040039

Karunanayake CP, Dosman JA, Ayas N, Fenton M, Seeseequasis J, Lindain R, Seesequasis W, McMullin K, Kachroo MJ, Ramsden VR, et al. Association of Insomnia with Functional Outcomes Relevant to Daily Behaviors and Sleep-Related Quality of Life among First Nations People in Two Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada. Clocks & Sleep. 2024; 6(4):578-588. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep6040039

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarunanayake, Chandima P., James A. Dosman, Najib Ayas, Mark Fenton, Jeremy Seeseequasis, Reynaldo Lindain, Warren Seesequasis, Kathleen McMullin, Meera J. Kachroo, Vivian R. Ramsden, and et al. 2024. "Association of Insomnia with Functional Outcomes Relevant to Daily Behaviors and Sleep-Related Quality of Life among First Nations People in Two Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada" Clocks & Sleep 6, no. 4: 578-588. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep6040039

APA StyleKarunanayake, C. P., Dosman, J. A., Ayas, N., Fenton, M., Seeseequasis, J., Lindain, R., Seesequasis, W., McMullin, K., Kachroo, M. J., Ramsden, V. R., King, M., Abonyi, S., Kirychuk, S., Koehncke, N., Skomro, R., & Pahwa, P. (2024). Association of Insomnia with Functional Outcomes Relevant to Daily Behaviors and Sleep-Related Quality of Life among First Nations People in Two Communities in Saskatchewan, Canada. Clocks & Sleep, 6(4), 578-588. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep6040039