Integrative Lighting Aimed at Patients with Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

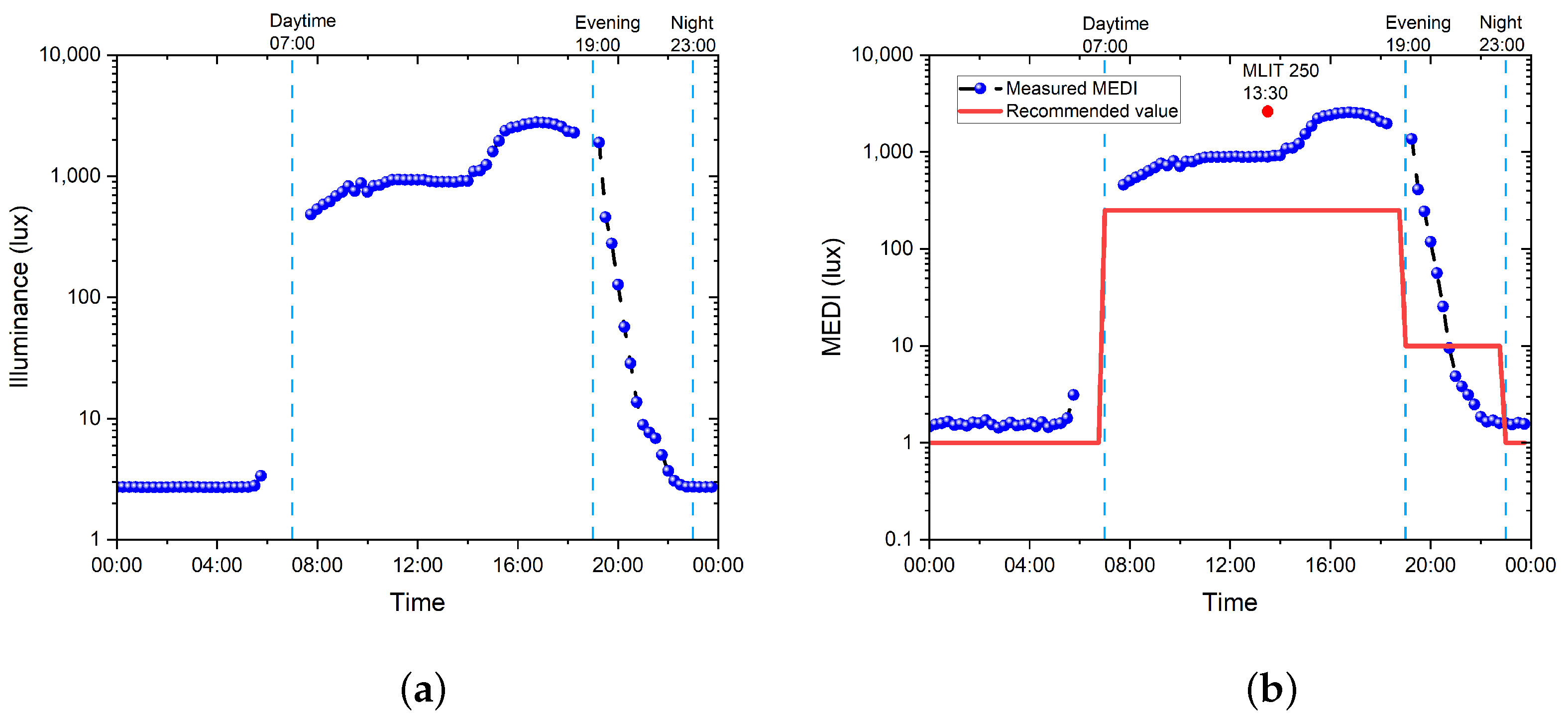

- Daytime: the recommended minimum MEDI is 250 lux at the eye measured in the vertical plane at ∼1.2 m height (i.e., vertical illuminance at eye level when seated), noting that, if available, daylight should be used in the first instance to meet these levels;

- Evening: this covers the light recommendations for residential and other indoor environments during the evening, starting at least 3 h before bedtime; the recommended maximum MEDI is 10 lux measured at the eye level in the vertical plane ∼1.2 m height. In order to help achieve this, where possible, white light should have a spectrum depleted in short wavelengths close to the peak of the melanopic action spectrum;

- Nighttime: the light recommendations for the sleep environment. The sleeping environment should be as dark as possible. The recommended maximum ambient MEDI is 1 lux measured at the position of the eye;

- For unavoidable activities where vision is required during the nighttime, the recommended maximum MEDI is 10 lux measured at the eye in the vertical plane at ∼1.2 m height.

2. Results

2.1. Measurement Scheme

2.2. Key Parameters

- Illuminance (lux): a measure of how much the incident light illuminates a given surface. It can be seen as how “bright” the reflected light is perceived by the human eye.The value should be high enough to provide enough lighting for people to see things clearly but not too high, as this causes discomfort glare. Depending on the work environment, the requirements can be found in DS/EN12464-1:2021 [37]. In addition, GLG has published its age-correlated recommendations for illuminance levels [36].

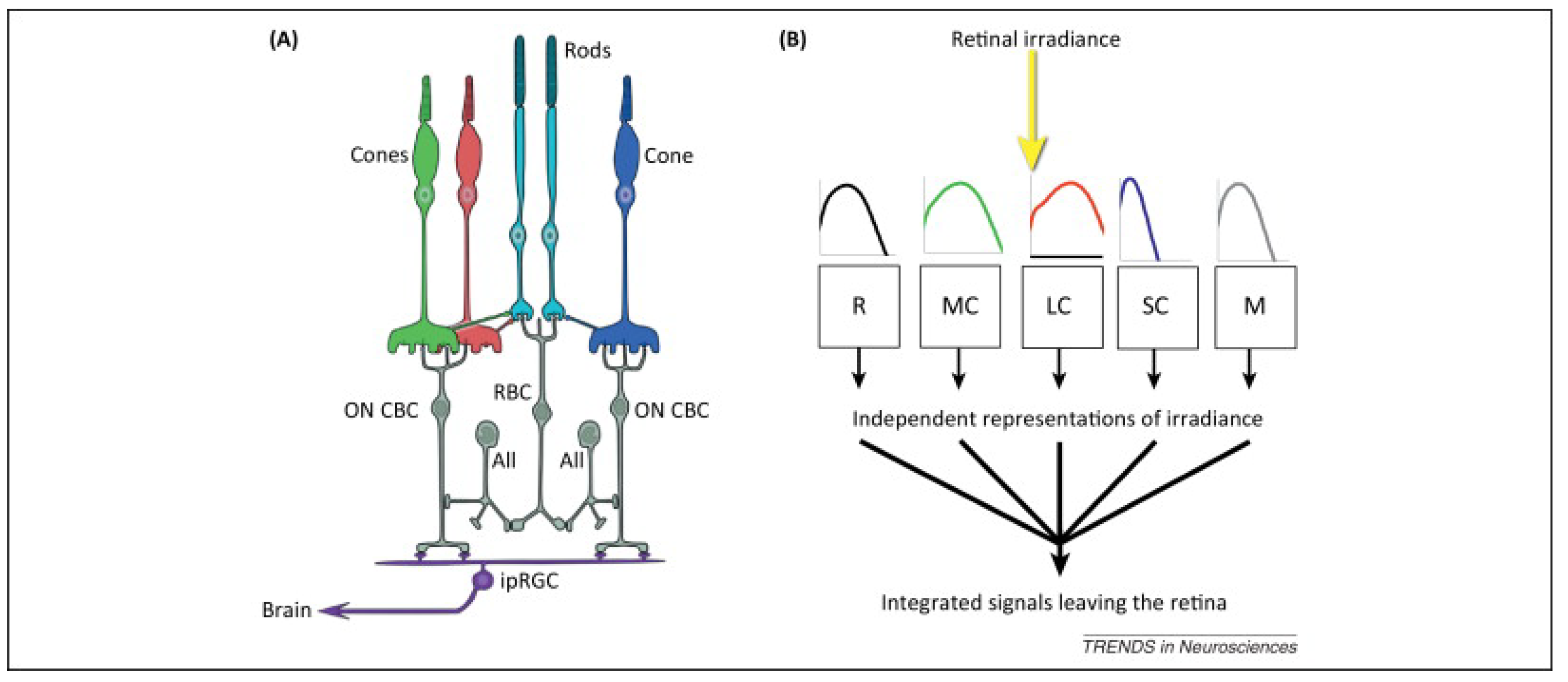

- MEDI (lux): this describes the response of the nonvisual photo-receptors, i.e., ipRGCs, in the human eye in correspondence to a standardized D65 illuminant. This response is indicative of the photo-biological effect of a given illumination condition on the circadian system of the exposed subjects and is a combination of the spectrum of light and intensity. It provides an indication of the ability of a light stimulus to entrain the circadian system as well as suppress melatonin in the blood. A high MEDI during the day is usually supportive of alertness, the circadian rhythm, and a good night’s sleep. At night-time, a low MEDI promotes sleep [23].

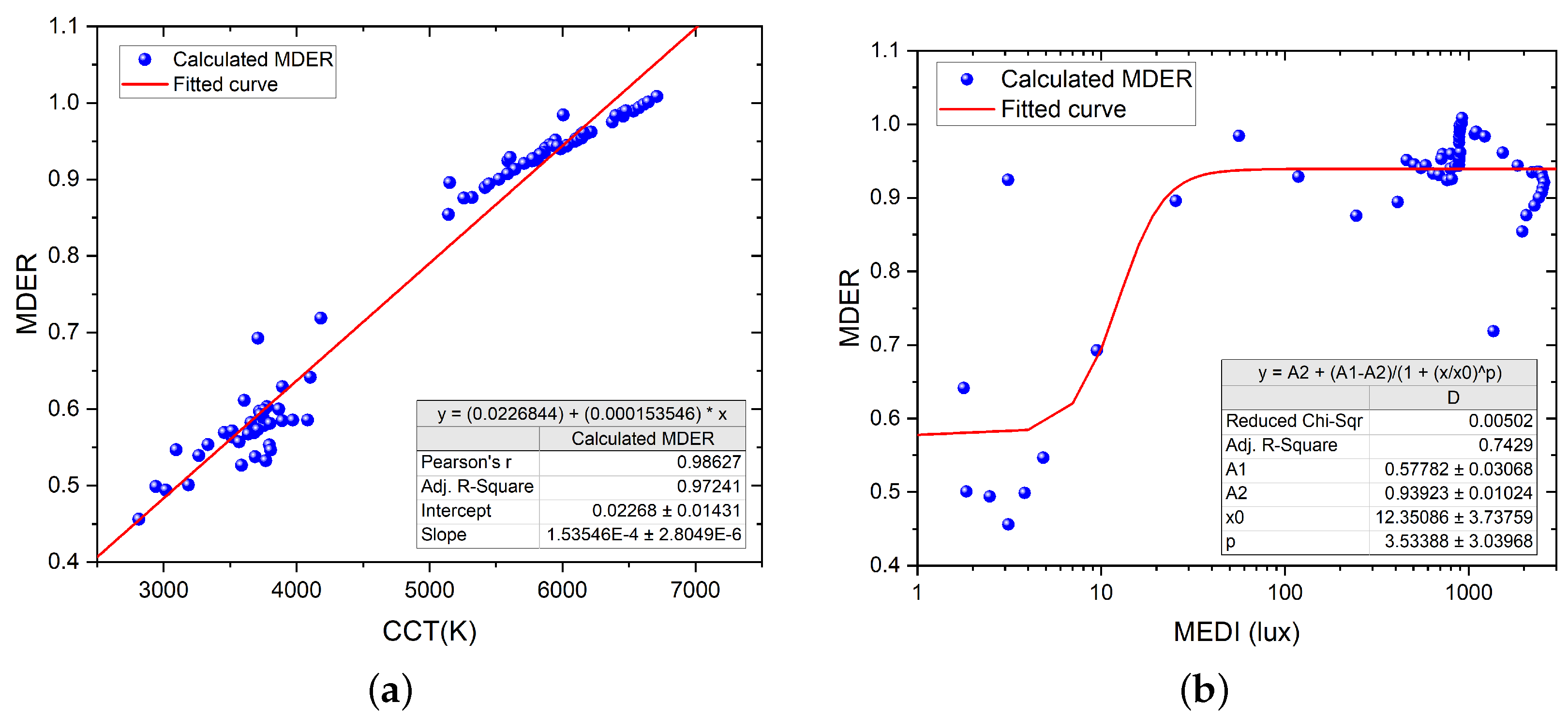

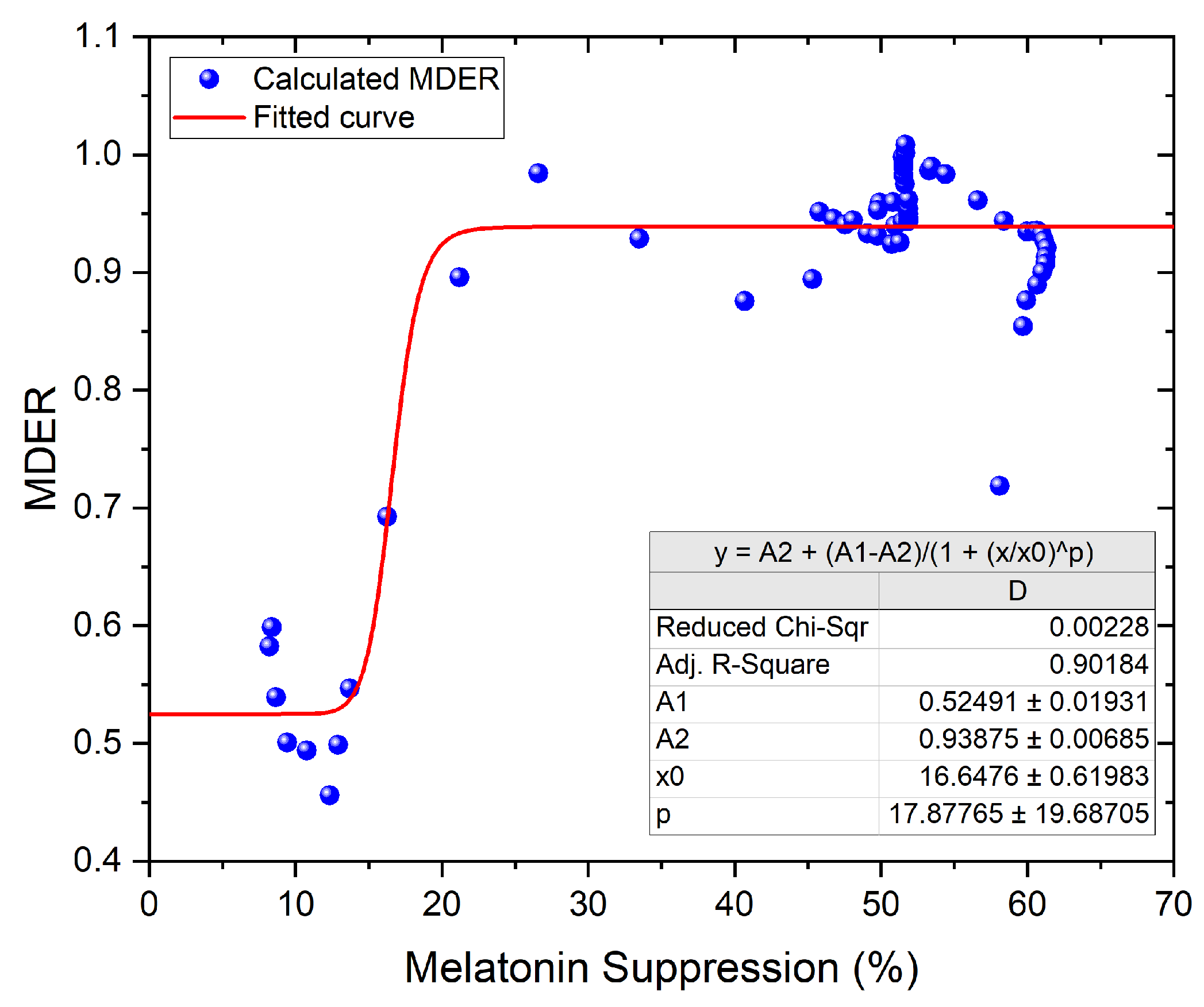

- Melanopic daylight efficacy ratio (MDER): a spectral metric of the biological effect of an artificial light source compared to daylight (6500 K), which is then divided by the photopic response (ratio) to estimate the nonvisual light. The ratio provides a shorthand to estimate the relative nonvisual stimulus of a light source while maintaining visual standards. As a rule of thumb, a higher ratio will have a higher melanopic content (a DER bigger than 0.8 represents stimulating light), and a lower ratio represents lower melanopic content (a DER lower than 0.3 represents sleep-promoting light). Typically, artificial lighting has a lower biological effect than daylight, with the MDER being below 1 [23].

- Correlated color temperature (CCT, K): a visual measure to describe the colored appearance provided by a white light source perceived by the human eye. CCT is based on the temperature in kelvin needed to warm a blackbody to achieve the color appearance. A range of 2700–3000 K is called ‘warm color’, and a CCT above 5000 K is called ‘cool color’.

- Color rendering index (CRI, Ra): the ability of a light source to render the colors of various objects faithfully in comparison with an ideal or natural light source. The higher the CRI, the more accurate the color rendering of a given light source is, with the maximum achievable value being 100.

2.3. Point Measurement

2.4. Data Logging

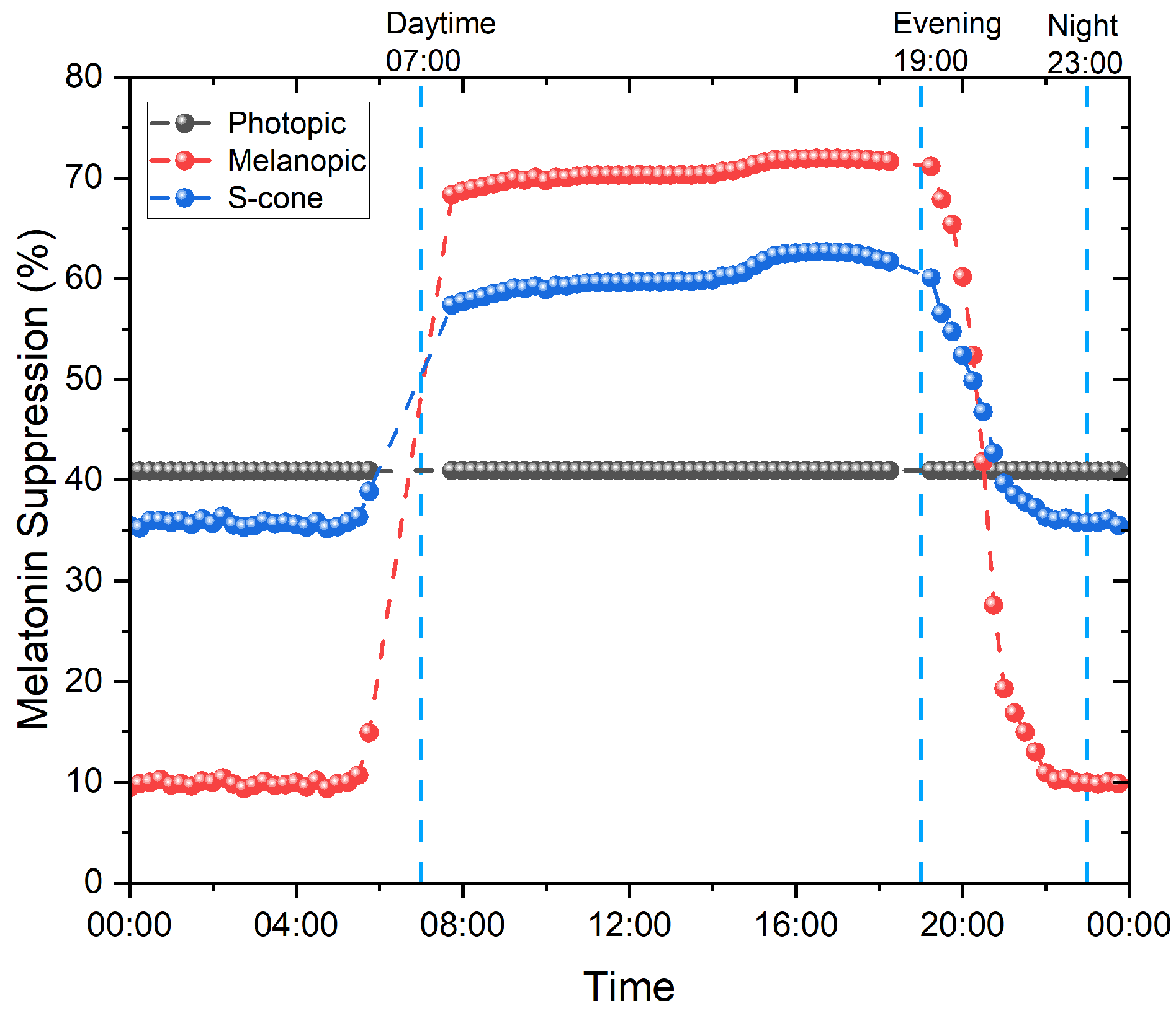

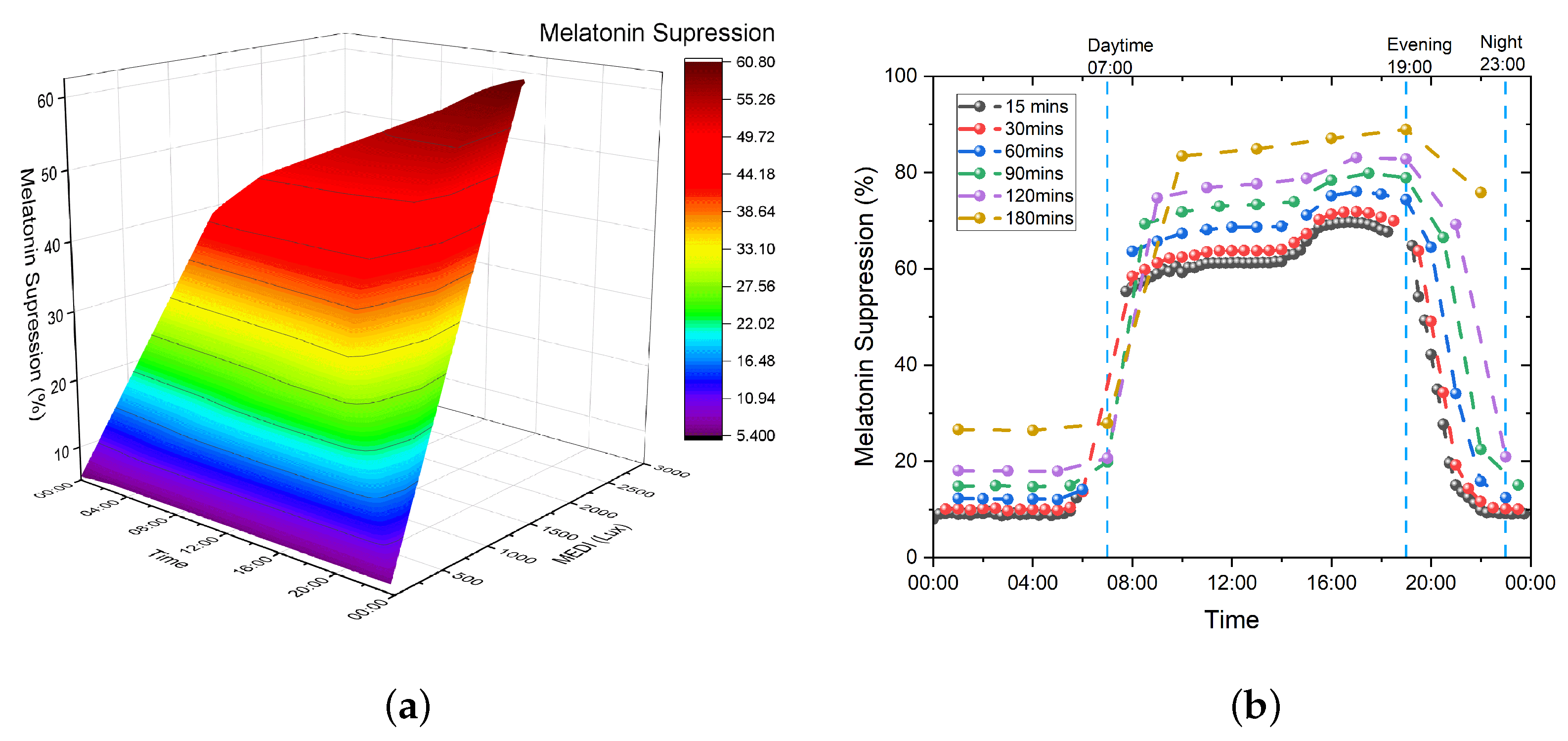

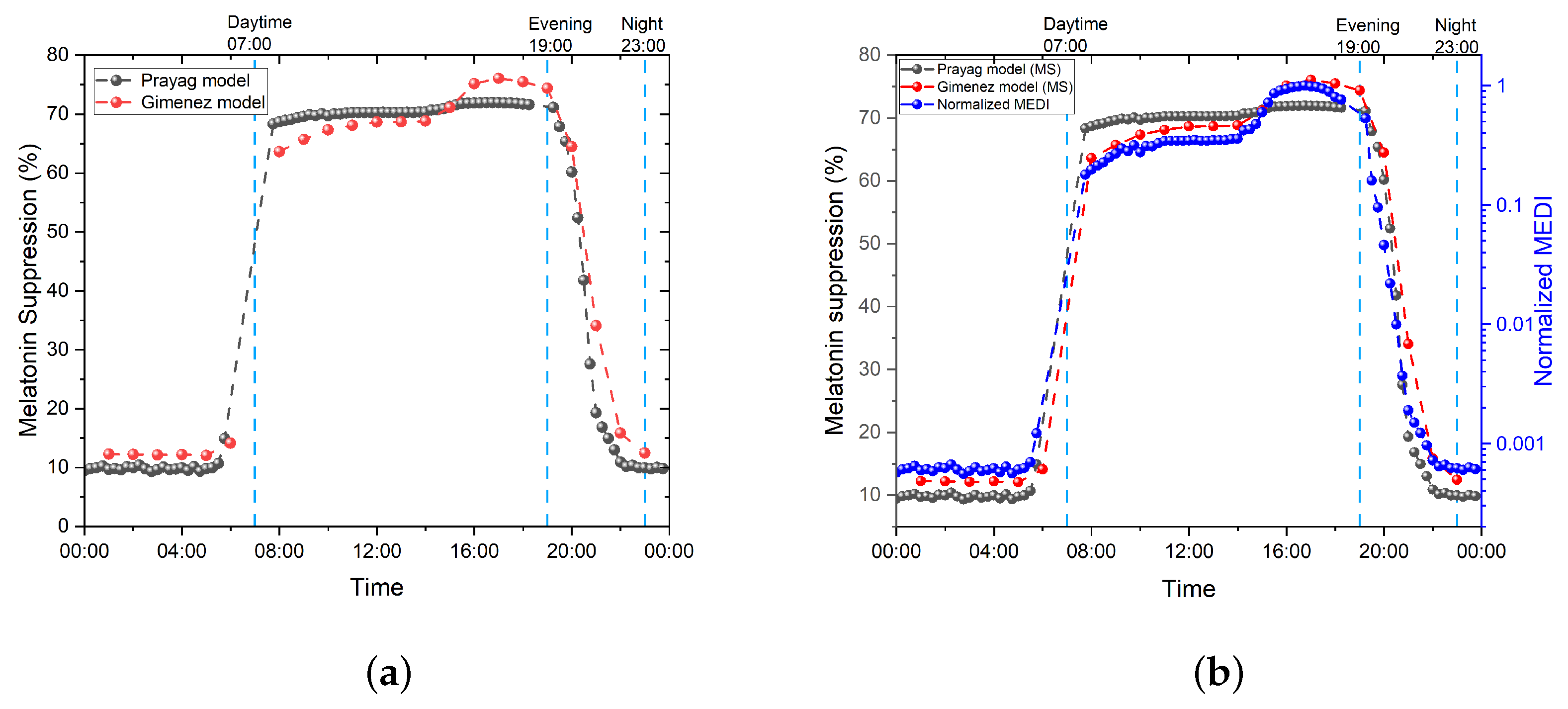

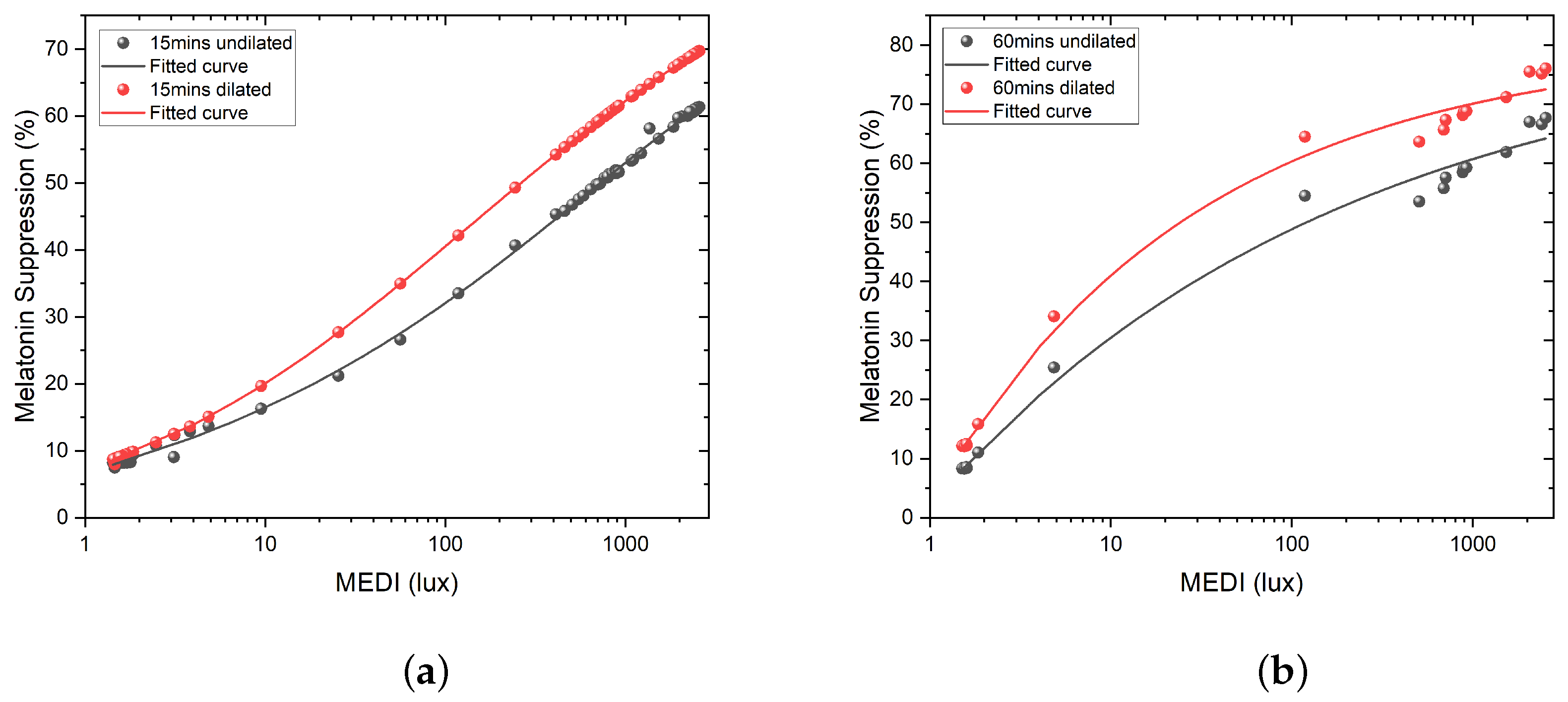

3. Melatonin Suppression

3.1. Prayag et al.

3.2. Giménez et al.

3.3. Numerical Evaluation of the Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Results

4.2. Perspectives and Future Work

4.3. Limitations

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Materials and Equipment

5.2. Data Processing and Presenting the Results

5.3. Setup and Measurement Procedure of the Case Study

- Five measurement points have been chosen. Points 1 to 3 were chosen near the bed, imitating the patient-lying position in the bed facing a different direction;

- Points 1 and 2 at 90 cm in height, facing west (window) and east, respectively, and point 3 at 104 cm in height, facing south;

- Points 4 and 5 were chosen on each side of the bed at 175 cm in height, imitating the medical staff performing visual tasks in a standing position. Please note that this height would correspond to a male nurse or doctor, and therefore, a lower height should have been considered to assess the light exposure of a female nurse. However, the difference is too small to have a huge impact;

- The spectrometer was mounted on a tripod facing the sensor, as indicated above, imitating eye height.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Results

6.2. Significance and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IF | Image-Forming |

| NIF | Non-Image-Forming |

| ipRGCs | Intrinsically Photo-sensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells |

| -opic EDIs | -opic Equivalent Daylight Illuminances |

| MEDI | Melanopic-EDI |

| GLG | Good Light Group |

| CIE | Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage |

| MDER | Melanopic Daylight Efficacy Ratio |

| CCT | Correlated Color Temperature |

| TAT | Time Above Threshold |

| MLIT | Mean Light Timing |

| SPD | Spectral Power Distribution |

| SI | International System of Units |

| CS | Circadian Stimulus |

| CLA | Circadian Light |

References

- Gooley, J.J.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Brainard, G.C.; Kronauer, R.E.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Spectral responses of the human circadian system depend on the irradiance and duration of exposure to light. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 31ra33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalsa, S.B.S.; Jewett, M.E.; Cajochen, C.; Czeisler, C.A. A phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjects. J. Physiol. 2003, 549, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souman, J.L.; Tinga, A.M.; Pas, S.F.T.; van Ee, R.; Vlaskamp, B.N.S. Acute alerting effects of light: A systematic literature review. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 337, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajochen, C.; Münch, M.; Kobialka, S.; Kräuchi, K.; Steiner, R.; Oelhafen, P.; Orgül, S.; Wirz-Justice, A. High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijk, D.-J.; Archer, S.N. Light, sleep, and circadian rhythms: Together again. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, e1000145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prayag, A.S.; Münch, M.; Aeschbach, D.; Chellappa, S.L.; Gronfier, C. Light modulation of human clocks, wake, and sleep. Clocks Sleep 2019, 1, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, L.A.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Hosken, I.T.; McGlashan, E.M.; Anderson, C.; Lack, L.C.; Lockley, S.W.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Cain, S.W. Increased sensitivity of the circadian system to light in delayed sleep–wake phase disorder. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 6249–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diakite-Kortlever, A.; Knoop, M. Non-image forming potential in urban settings—An approach considering orientation-dependent spectral properties of daylight. Energy Build. 2022, 265, 112080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.P., Jr.; McHill, A.W.; Birks, B.R.; Griffin, B.R.; Rusterholz, T.; Chinoy, E.D. Entrainment of the human circadian clock to the natural light-dark cycle. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 1554–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Maierová, L.; Cajochen, C.; Scartezzini, J.-L.; Münch, M. Optimized office lighting advances melatonin phase and peripheral heat loss prior bedtime. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.H., II; Walton, J.C.; DeVries, A.C.; Nelson, R.J. Circadian rhythm disruption and mental health. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alachkar, A.; Lee, J.; Asthana, K.; Monfared, R.V.; Chen, J.; Alhassen, S.; Samad, M.; Wood, M.; Mayer, E.A.; Baldi, P. The hidden link between circadian entropy and mental health disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, A.C.; Windred, D.P.; Rutter, M.K.; Olivier, P.; Vetter, C.; Saxena, R.; Lane, J.M.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Cain, S.W. Day and night light exposure are associated with psychiatric disorders: An objective light study in >85,000 people. Nat. Ment. Health 2023, 1, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, M.; Martin, S.K.; Lee, C.; Eastman, C.I. The effects of prior light history on the suppression of melatonin by light in humans. J. Pineal Res. 2002, 33, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Czeisler, C.A. The human circadian system adapts to prior photic history. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.A.; Schoen, M.W.; Czeisler, C.A. Adaptation of human pineal melatonin suppression by recent photic history. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 3610–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, S.M.; Malkani, R.G.; Zee, P.C. Circadian disruption and human health: A bidirectional relationship. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Morris, C.J.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. Effects of circadian misalignment on cognition in chronic shift workers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirz-Justice, A.; Bromundt, V.; Cajochen, C. Circadian disruption and psychiatric disorders: The importance of entrainment. Sleep Med. Clin. 2009, 4, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, G.D.M.; Skene, D.J.; Arendt, J.; Cade, J.E.; Grant, P.J.; Hardie, L.J. Circadian rhythm and sleep disruption: Causes, metabolic consequences, and countermeasures. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 584–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.J.; Peirson, S.N.; Berson, D.M.; Brown, T.M.; Cooper, H.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gamlin, P.D.; Lockley, S.W.; O’hagan, J.B.; et al. Measuring and using light in the melanopsin age. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Brainard, G.; Cajochen, C.; Czeisler, C.; Hanifin, J.; Lockley, S.; Lucas, R.; Münch, M.; O’Hagan, J.; Peirson, S.; et al. Recommendations for healthy daytime, evening, and night-time indoor light exposure. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIE S 026/E: 2018; CIE System for Metrology of Optical Radiation for ipRGC-Influenced Responses to Light. CIE Central Bureau: Vienna, Austria, 2018.

- CIE S 017/E:2020; ILV: International Lighting Vocabulary, 2nd ed. CIE: Vienna, Austria, 2020.

- Schlangen, L.J.M.; Price, L.L.A. The lighting environment, its metrology, and non-visual responses. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 624861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DS/ISO/CIE 11664-2:2022; Colorimetry—Part 2: CIE Standard Illuminants: DS/ISO/CIE 11664-2:2022. CIE: Vienna, Austria, 2022.

- Schlangen, L.J.M.; Belgers, S.; Cuijpers, R.H.; Zandi, B.; Heynderickx, I. Correspondence: Designing and specifying light for melatonin suppression, non-visual responses and integrative lighting solutions–establishing a proper bright day, dim night metrology. Light. Res. Technol. 2022, 54, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, T.; Houser, K. Correlated color temperature is not a suitable proxy for the biological potency of light. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.F.; Czeisler, C.A. Age-related change in the relationship between circadian period, circadian phase, and diurnal preference in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 2002, 318, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, I.Y.; Kripke, D.F.; Elliott, J.A.; Youngstedt, S.D.; Rex, K.M.; Hauger, R.L. Age-related changes of circadian rhythms and sleep-wake cycles. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajochen, C.; Münch, M.; Knoblauch, V.; Blatter, K.; Wirz-Justice, A. Age-related changes in the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niggemyer, K.A.; Begley, A.; Monk, T.; Buysse, D.J. Circadian and homeostatic modulation of sleep in older adults during a 90-minute day study. Sleep 2004, 27, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, P.R.; Watson, J.; Gilmour, G.S.; Gaillard, F.; Sauvé, Y. Differential changes in retina function with normal aging in humans. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2011, 122, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerth, C.; Garcia, S.M.; Ma, L.; Keltner, J.L. Multifocal electroretinogram: Age-related changes for different luminance levels. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2002, 240, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez, M.C.; Kanis, M.J.; Beersma, D.G.M.; van der Pol, B.A.E.; van Norren, D.; Gordijn, M.C.M. In vivo quantification of the retinal reflectance spectral composition in elderly subjects before and after cataract surgery: Implications for the non-visual effects of light. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2010, 25, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good Light Group. Good Light Guide, for Healthy, Daytime-Active People; Good Light Group: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DS/EN 12464-1:2021; Lighting at Indoor Workplaces—Guide to DS/EN 12464-1:2021. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Reid, K.J.; Santostasi, G.; Baron, K.G.; Wilson, J.; Kang, J.; Zee, P.C. Timing and intensity of light correlate with body weight in adults. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, R. Fundamentals of circadian entrainment by light. Light. Res. Technol. 2021, 53, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, A.S.; Najjar, R.P.; Gronfier, C. Melatonin suppression is exquisitely sensitive to light and primarily driven by melanopsin in humans. J. Pineal Res. 2019, 66, e12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M. Melanopic illuminance defines the magnitude of human circadian light responses under a wide range of conditions. J. Pineal Res. 2020, 69, e12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, M.C.; Stefani, O.; Cajochen, C.; Lang, D.; Deuring, G.; Schlangen, L.J.M. Predicting melatonin suppression by light in humans: Unifying photoreceptor-based equivalent daylight illuminances, spectral composition, timing and duration of light exposure. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 72, e12786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, G.C.; Hanifin, J.P.; Greeson, J.M.; Byrne, B.; Glickman, G.; Gerner, E.; Rollag, M.D. Action Spectrum for Melatonin Regulation in Humans: Evidence for a Novel Circadian Photoreceptor. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 6405–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Thapan, K.; Arendt, J.; Revell, V.L.; Skene, D.J. S-cone contribution to the acute melatonin suppression response in humans. J. Pineal Res. 2021, 71, e12719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilaire, M.A.S.; Ámundadóttir, M.L.; Rahman, S.A.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Rüger, M.; Brainard, G.C.; Czeisler, C.A.; Andersen, M.; Gooley, J.J.; Lockley, S.W. The Spectral Sensitivity of Human Circadian Phase Resetting and Melatonin Suppression to Light Changes Dynamically with Light Duration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, 2205301119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitschan, M.; Lazar, R.; Yetik, E.; Cajochen, C. No Evidence for an S Cone Contribution to Acute Neuroendocrine and Alerting Responses to Light. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1297–R1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, M.; Figueiro, M. Light as a circadian stimulus for architectural lighting. Light. Res. Technol. 2018, 50, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, M.S.; Nagare, R.; Figueiro, M.G. Modeling circadian phototransduction: Quantitative predictions of psychophysical data. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 615322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanh, T.Q.; Vinh, T.Q.; Bodrogi, P. Numerical correlation between non-visual metrics and brightness metrics—Implications for the evaluation of indoor white lighting systems in the photopic range. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Toledo, L.H.S.; Moraes, M.N.; Poletini, M.d.O.; Neto, J.C.; Baron, J.; Mota, T. Modeling the Influence of Nighttime Light on Melatonin Suppression in Humans: Milestones and Perspectives. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 16, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Chen, Z.; Jiao, F.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Z.; Deng, C.; Zhang, H.; Dong, B.; Xi, X.; Kang, X.; et al. α-Opic Flux Models Based on the Five Fundus Photoreceptors for Prediction of Light-Induced Melatonin Suppression. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.B.; Yellott, J.I. A unified formula for light-adapted pupil size. J. Vis. 2012, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitschan, M. Photoreceptor inputs to pupil control. J. Vis. 2019, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, J. New Prospectives on Light Adaptation of Visual System Research with the Emerging Knowledge on Non-Image-Forming Effect. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 1019460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauner, J.; Plischke, H.; Strasburger, H. Spectral dependency of the human pupillary light reflex. Influences of pre-adaptation and chronotype. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0253030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, B.; Khanh, T.Q. Deep learning-based pupil model predicts time and spectral dependent light responses. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelders, T.; Leenheers, T.; Gordijn, M.C.M.; Hut, R.A.; Beersma, D.G.M.; Wams, E.J. Melanopsin- and L-Cone–Induced Pupil Constriction Is Inhibited by S- and M-Cones in Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitschan, M.; Jain, S.; Brainard, D.H.; Aguirre, G.K. Opponent Melanopsin and S-Cone Signals in the Human Pupillary Light Response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15568–15572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babilon, S.; Beck, S.; Khanh, T. A field test of a simplified method of estimating circadian stimulus. Light. Res. Technol. 2022, 54, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babilon, S.; Beck, S.; Kunkel, J.; Klabes, J.; Myland, P.; Benkner, S.; Khanh, T.Q. Measurement of Circadian Effectiveness in Lighting for Office Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cano, A.; Aporta, J. Optimization of Lighting Projects Including Photopic and Circadian Criteria: A Simplified Action Protocol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, P.; Ding, J.; Yao, Q.; Ju, J. The Circadian Effect Versus Mesopic Vision Effect in Road Lighting Applications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swope, C.B.; Rong, S.; Campanella, C.; Vaicekonyte, R.; Phillips, A.J.; Cain, S.W.; McGlashan, E.M. Factors associated with variability in the melatonin suppression response to light: A narrative review. Chronobiol. Int. 2023, 40, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmeyer, S.; Andersen, M. Towards a framework for light-dosimetry studies: Quantification metrics. Light. Res. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webler, F.S.; Spitschan, M.; Foster, R.G.; Andersen, M.; Peirson, S.N. What is the ‘spectral diet’ of humans? Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 30, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Kalavally, V.; Cain, S.W.; Phillips, A.J.K.; McGlashan, E.M.; Tan, C.P. Wearable light spectral sensor optimized for measuring daily α-opic light exposure. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 27612–27627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://lystechnologies.io/for-research/ (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Available online: https://www.circadianhealth.com.au/ (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Available online: https://www.monash.edu/medicine/news/latest/2021-articles/let-there-be-light-but-make-sure-its-the-natural,-healthy-kind (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Available online: https://www.monash.edu/turner-institute/news-and-events/latest-news/2021-articles/innovative-light-sensor-to-help-protect-against-harmful-artificial-lighting-in-preparation-for-mass-production (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Available online: https://condorinst.com/en/actlumus-actigraph/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Available online: https://nanolambda.myshopify.com/products/xl-500-ble-spectroradiometer (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Petrowski, K.; Schmallbach, B.; Niedling, M.; Stalder, T. The Effects of Post-Awakening Light Exposure on the Cortisol Awakening Response in Healthy Male Individuals. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.M.; Khalsa, S.B.S.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Cajochen, C.; Lockley, S.W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Wright, K.P., Jr. Acute effects of bright light exposure on cortisol levels. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2010, 25, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrowski, K.; Buehrer, S.; Niedling, M.; Schmalbach, B. The effects of light exposure on the cortisol stress response in human males. Stress 2021, 24, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.A.; Wright, K.P.; Lockley, S.W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Gronfier, C. Characterizing the temporal Dynamics of Melatonin and Cortisol Changes in Response to Nocturnal Light Exposure. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S.-N.; Zhang, Z.; Ribelayga, C.P.; Zhong, Y.-M.; Zhang, D.-Q. Multiple cone pathways are involved in photic regulation of retinal dopamine. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinane, C.; Calligaro, H.; Jandot, A.; Coutanson, C.; Haddjeri, N.; Bennis, M.; Dkhissi-Benyahya, O. Dopamine modulates the retinal clock through melanopsin-dependent regulation of cholinergic waves during development. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korshunov, K.S.; Blakemore, L.J.; Trombley, P.Q. Dopamine: A Modulator of Circadian Rhythms in the Central Nervous System. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Mangel, S.C. Dopamine-Mediated Circadian and Light/Dark-Adaptive Modulation of Chemical and Electrical Synapses in the Outer Retina. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 647541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Reed, M.C. A mathematical model of circadian rhythms and dopamine. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2021, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Witelski, T.P. Uncovering the Dynamics of a Circadian-Dopamine Model Influenced by the Light–Dark Cycle. Math. Biosci. 2022, 344, 108764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://luox.app/ (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Spitschan, M.; Mead, J.; Roos, C.; Lowis, C.; Griffiths, B.; Mucur, P.; Herf, M.; Nam, S.; Veitch, J.A. luox: Validated reference open-access and open-source web platform for calculating and sharing physiologically relevant quantities for light and lighting. Wellcome Open Res. 2022, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.canva.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2023).

| Recommended Minimal Light Levels on the Eye in MEDI | <30 Years | ∼50 Years | >75 Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime (7 a.m.–7 p.m.) | MEDI ≥ 250 lux | MEDI ≥ 300 lux | MEDI ≥ 425 lux |

| Evening (7 p.m.–11 p.m.) | MEDI ≤ 10 lux | MEDI ≤ 12 lux | MEDI ≤ 17 lux |

| Nighttime (11 p.m.–7 a.m.) | MEDI ≤ 1 lux | MEDI ≤ 1 lux | MEDI ≤ 2 lux |

| Measurement Point | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation | West | East | South | West | East |

| Measurement time | 10:03:34 a.m. | 10:04:31 a.m. | 10:08:45 a.m. | 10:14:22 a.m. | 10:17:50 a.m. |

| Measurement Height (cm) | 90 | 90 | 104 | 175 | 175 |

| Illuminance (lx) | 234.2 | 148 | 190.3 | 278.8 | 231.9 |

| CCT (K) | 7475 | 5848 | 6793 | 7924 | 6198 |

| CRI (Ra) | 96.4 | 96.3 | 96.4 | 96.1 | 96.1 |

| MEDI (lx) | 252.8 | 136.6 | 193.9 | 310.8 | 222.1 |

| MDER | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 1.12 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, X.; Soreze, T.S.C.; Ballegaard, M.; Petersen, P.M. Integrative Lighting Aimed at Patients with Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Clocks & Sleep 2023, 5, 806-830. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep5040052

Zeng X, Soreze TSC, Ballegaard M, Petersen PM. Integrative Lighting Aimed at Patients with Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Clocks & Sleep. 2023; 5(4):806-830. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Xinxi, Thierry Silvio Claude Soreze, Martin Ballegaard, and Paul Michael Petersen. 2023. "Integrative Lighting Aimed at Patients with Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders" Clocks & Sleep 5, no. 4: 806-830. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep5040052

APA StyleZeng, X., Soreze, T. S. C., Ballegaard, M., & Petersen, P. M. (2023). Integrative Lighting Aimed at Patients with Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Clocks & Sleep, 5(4), 806-830. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep5040052