1. Introduction

The recent development of

spatial transcriptomics (ST) biotechnologies, such as CosMx and Xenium machines released in December 2022, has shown great potential for the improvement of cancer diagnosis and treatment; see [

1] and the review article [

2]. The CosMx machine, i.e.,

CosMx Spatial Molecular Imager, produces data consisting of images of tissues and cells, as well as gene expression at the single-cell level with detailed spatial location information which can be processed into

single-cell ST data with

C as cell type and

as its spatial location [

1]. The earlier generation of, or something similar to, single-cell ST data, such as CODEX [

3], Visium [

4], GeoMx (started in 2019; see [

5]), etc., does not offer the same data information as CosMx. For instance, CODEX only focuses on protein markers, which gives data with many fewer analytes than ST data produced by the CosMx machine, though also can be processed into the same data form

; see [

6,

7], etc. Visium and GeoMx data provide the average information of many cells in a given area, but not at the single-cell level; see the review papers [

6,

8,

9,

10], among others.

For the general version of ST data, i.e., the data with gene expression (not single-cell type) and spatial location, numerous computational and statistical methods have been developed to detect the “

Spatial Domain” which contains cells with similar gene expression profiles; see papers [

11,

12,

13], among others. For data with cell type and spatial location, i.e., data

with

C as cell type and

as its spatial location, various “

Cellular Neighborhood” (CN) methods have been developed to identify clusters, each having a unique composition of cell types, which are based on the

kNN or modified

kNN compositional matrix and clustering methods; see [

11,

14,

15,

16], among others. Due to data structure differences, Bhate et al. [

14] pointed out that CNs are not the same as spatial domains. The methods for network-based “

Community” detection have been developed for matrix obtained from symmetric network; see [

17,

18], among others. However, none of these works is applicable or suitable for the huge dataset from above mentioned very recent single-cell ST data produced by CosMx and Xenium.

In cancer research, studies have shown that data with the same form as single-cell ST data can help identify groups of cell types with special characteristics that are associated with survival rate and different treatment outcomes. In colorectal cancer study, Schurch et al. [

15] used CODEX data to identify nine distinct

cellular neighborhoods with different characteristics of the immune tumor microenvironment, which led to the discovery of the enrichment of PD-

CD

T cells in a specific granulocyte cellular neighborhood that was associated with better survival for high-risk patients. In a triple negative breast cancer study, Shiao et al. [

19] also used CODEX data to identify 12 distinct

spatial districts which helped detect and analyze different immune response to treatment therapy for two groups of patients. In this article, for single-cell ST data we define

ST-Community as a collection of cells with distinct cell-type composition and similar neighboring patterns based on nearby cell-percentages. This means that each cell in the st-community has similar nearby cell-percentages as neighboring cells in the same community, which characterizes the tumor microenvironment, and such concept of st-community includes “cellular neighborhoods” (CNs) detected in [

15] and “spatial districts” detected in [

19] as special cases. Note that a st-community contains multiple types of cells and may be located at different parts of the data, not just concentrated in one spatial area.

In such context,

st-community detection for single-cell ST data obtained by new single-cell biotechnologies, such as CosMx and Xenium, is of great importance in cancer research. Considering the information of neighboring cell types, the discussion given in

Section 2 shows that the initial step should process single-cell ST data into

compositional data [

20], then use an appropriate clustering method for st-community detection. The clustering method used in [

19] was Leiden method [

21] based on vectors formed by a graph neural network, but Leiden method is not applicable to compositional data. The clustering method used in [

15] was the

k-means method [

22,

23,

24] for compositional data.

Other existing clustering methods which are applicable to compositional data are as follows:

Elbow k-means method [

25],

Gap k-means method [

26],

Mclust algorithm [

27,

28],

DBSCAN algorithm [

29], and

HDBSCAN algorithm [

30,

31]. However, the single-cell ST data produced by CosMx is usually too huge for these existing clustering methods to handle, and some of them are under too many unjustifiable assumptions.

Due to these reasons, this article first proposes a novel compositional data method for single-cell ST data, called

disk compositional data (DCD), which particularly considers the features of ST data produced by recent new biotechnologies and is the initial step to provide each cell with nearby cell-percentages in the neighborhood of a disk using the chosen radius, then proposes an innovative computation method for st-community detection, called

DCD-TMHC method, where TMHC is constructed based on the

2-means (TM) method and

hierarchical clustering (HC) method [

32,

33]. This proposed DCD-TMHC computation method is generally applicable to single-cell ST data or the data type with the same data form

. The simulation studies presented in

Section 3 show that DCD-TMHC method consistently performs better than above listed clustering methods.

Further, we apply the proposed DCD-TMHC method and other clustering methods, including CN methods, to analyze a CosMx breast cancer dataset, which is a single-cell ST dataset with 9 different cell types and was produced by the NanoString Company. Based on the data analysis results, we compare the performance of these methods via logistic regression model, which shows that our proposed DCD-TMHC method is superior to other methods, especially in terms of assessment for different cancer categories. Thus, the DCD-TMHC method proposed in this article will be helpful and have an impact on future cancer research based on single-cell ST data for the improvement of cancer diagnosis and treatments.

The rest of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews single-cell ST data and existing methods, and proposes the novel st-community detection method DCD-TMHC;

Section 3 presents simulation study results;

Section 4 conducts CosMx breast cancer data analysis using the proposed DCD-TMHC method and alternative methods, then makes comparison via logistic regression analysis; and

Section 5 gives discussion and conclusion.

2. ST-Community Detection of Single-Cell ST Data

Spatial Transcriptomics (ST) techniques have existed for almost a decade, but only were available at the institutions where they were developed. Recently, new techniques, such as CosMx and Xenium, have been commercialized and made ST technology more accessible [

7]. ST quantifies messenger RNA transcripts for gene expression at the single-cell level with spatial context. In cancer research, it is often very difficult to extract RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues because they are obtained previously from a patient’s treatment, thus not “fresh” samples; see review paper [

8]. Now, ST technologies by CosMx and Xenium can handle and process such tissues. CosMx allows the quantification of 1000+ RNA and 64+ protein targets, and Xenium can be run on a panel with maximum of 480 gene markers.

In particular, the above mentioned CosMx breast cancer data, with 9 different cell types, provide 19–25

fields of view (FOVs) from each breast cancer tissue sample, which are small selected rectangular regions, and the location

of a cell

C in all FOVs from the same tissue sample is determined based on a common origin. Within each FOV, there are thousands of cells and their spatial information.

Figure 1 shows an example of 25 FOVs produced by CosMx from one patient’s primary breast cancer sample, where each FOV is a small grid portion shown as a colored rectangle. Notice that some FOVs are adjacent to each other, while others are more distant from each other.

As mentioned in

Section 1, the

st-community detection for single-cell ST data obtained by new and recent technologies is of great importance in cancer research. To identify the neighboring pattern of each cell based on nearby cell-percentages, the initial step of st-community detection is to conduct data processing to turn single-cell ST data into

compositional data [

20], which assigns cell proportion or cell-percentage in the neighborhood for each cell type under consideration. In [

15] for colorectal cancer and in [

34] for lung cancer, both had the same data form

as single-cell ST data, and both had their data processed into compositional data first, then used

k-means method [

22,

23,

24] to obtain st-communities in their studies.

2.1. Disk Compositional Data Matrix

For single-cell ST data, this subsection reviews the kNN compositional data matrix, proposes our disk compositional data (DCD) matrix, and gives comparison discussion which concludes that DCD matrix is far more informative and accurate.

For data

with cell type and spatial location, both [

15] and [

34] used the

k-nearest neighbor (

kNN) method to obtain compositional data by using

, which is the most commonly used method in computational biology literature. Below, we describe the

kNN compositional data matrix obtained from one sample.

Suppose that sample

contains

cells with a total of

m different cell types. For cell

in sample

, let

be the total number of cell type

j among

k nearest cells in sample

around

, then the

kNN compositional data matrix for sample

is given by:

where

is an

matrix, and its row is the compositional vector given by:

If single-cell ST data

contains

q samples

with total numbers of cells

, respectively, and each sample

contains the same

m different cell types, then the

kNN compositional data matrix for

is given by:

where

is an

matrix with

, and each

matrix

is obtained in the same way as shown in above Equation (

1). Note that matrix

reflects the neighboring cell patterns and restricts overly large values by Equation (

2).

In Schurch et al. [

15],

cancer samples with a total cell number

give sample cell average as 3784. In Enfield et al. [

34],

cancer samples with a total cell number

million give sample cell average as

. In comparison, the above mentioned CosMx breast cancer data contains

cancer tissue samples with a total cell number

, which gives a much bigger sample cell average as

and a total of

FOVs. The

kNN compositional data restricts the cell number in the neighborhood of any cell

C to be always the chosen constant

k, which can cause loss of information in the region with very high cell density, and can also cause misleading information from always counting the

k nearest cells. For single-cell ST data, the distance between cell

C and the

kth nearest cell can be very tiny, and can also be very huge. These motivate the construction of a novel, more flexible, more adaptive, and more informative approach for processing single-cell ST data into compositional data as follows.

Choosing a suitable radius

r, for any cell

in sample

with distance to the boundary of

(if the boundary exists obviously) no less than

, consider the following disk:

which contains all cells in sample

centered around cell

within radius

r, and let

be the total number of cell type

j included in disk

, then the

disk compositional data (DCD)

matrix for sample

is given by the

matrix

, where

with

as the total cell number in disk

and

as the total cell number in sample

with distance to the boundary no less than

. For single-cell ST data

containing

q samples

and each sample

containing the same

m different cell types, the disk compositional data (DCD) matrix for

is given by

where

is an

matrix with

, and each

matrix

is obtained in the same way as above

.

The exclusion of certain cells too close to the sample boundary, such as FOVs in CosMx data, in the above process of obtaining DCD matrix

is because their corresponding disks (

4) often contain too few cells, which give unreliable st-community detection. But in cases without obvious boundary like FOVs, such as simulation studies in

Section 3 of this article, no cells in data

are excluded to obtain DCD matrix

given by (

6).

In

Figure 2a below, one FOV from above mentioned CosMx breast cancer data is displayed, where the use of different radius

, respectively, is indicated. Note that near the boundary of the FOV, there are very few cells, and that for a smaller radius, disk

contains too few cells at times, while for a bigger radius, disk

contains too many cells. Thus, it is important to choose a suitable radius.

In

Figure 2b, for above mentioned CosMx breast cancer data with

cells, we use

to obtain the proposed DCD matrix

with

, then we display the histogram based on all total cell number

’s in disks

for all

FOVs.

In

Figure 2c, for above mentioned CosMx breast cancer data with

cells, since to our best knowledge

is the most commonly used, we use

to obtain the

kNN compositional data matrix

, then we display the histogram based on all distance

between cell

and its 10th nearest cell for all

FOVs.

Comparing histograms in

Figure 2, we see that

Figure 2b shows overwhelming disks

have total cell number

’s in the range of 20–60, while

Figure 2c shows that if using radius

for cell

, more than 400,000 disks

with

contain only 10 cells. Moreover,

Figure 2c, with the red line indicating the maximum value of

’s, shows that even using radius

, some disks

only contain 10 cells. Thus, the DCD matrix is far more informative and accurate than the

kNN compositional data matrix for huge single-cell ST data.

2.2. Existing Clustering Methods

After processing single-cell ST data into compositional data matrix, the next step is to use an appropriate clustering method for st-community detection. Below is a brief review of several existing and commonly used clustering methods in the literature.

Hierarchical Clustering Method: Suppose that

is a partition of dataset

, we obtain a further partition

of

via the following equation:

where

is any partition of

with one of them being the union of two

’s and the rest remaining the same, and

is the average of all points in

. If

N is the total number of points in

, for a selected

k, the

hierarchical clustering (HC) method [

24,

32,

33] is to obtain

k clusters by starting with a partition of

with

N clusters, repeatedly using (

7) and stopping at

. This method is very time-consuming, thus cannot handle the huge single-cell ST data.

-Means Method: For a selected

k, the

k-means method [

22,

23,

24] is to obtain

k clusters

of dataset

by solving the following equation:

where

is any partition of

and

is the average of all points in

.

Elbow-Means Method: The

Elbow method is using graphical method to choose optimal

k for the

k-means method given by above Equation (

8); see [

25].

Gap-Means Method: The

Gap statistics method is using statistical method to choose optimal

k for the

k-means method by Equation (

8); see [

26].

Mclust Algorithm: The

Mclust algorithm is to fit the data by different Gaussian mixture models, then use the

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to identify the optimal number of clusters by choosing the best Gaussian mixture model; see [

27,

28].

DBSCAN Algorithm: The

density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) algorithm uses a density-based method to identify clusters, a process in which two parameters

eps and

minPts are involved; see [

29].

HDBSCAN Algorithm: The

hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN) algorithm uses a density-based method together with a minimum spanning tree to identify clusters, a process in which one parameter

minPts is involved; see [

27,

31].

Both DBSCAN and HDBSCAN algorithms are very time-consuming. Other existing methods include

Seurat method [

35],

UMAP-Mclust method [

1], etc., which are incompatible for compositional data, and our simulation studies and data analysis show that these methods perform poorly for large single-cell ST data.

2.3. Data Transformation and SigClust

Before proposing our novel and innovative DCD-TMHC computation method in this article for st-community detection of single-cell ST data, we first need to describe Aitchison log-ratio transformation and SigClust method, which are used in the process of our newly developed DCD-TMHC method.

Aitchison Log-Ratio Transformation: The

Aitchison log-ratio transformation maps the compositional data from a simplex to real Euclidean space, which in many situations gives better results for clustering; see [

36,

37]. However, it has also been pointed out that in certain situations, such transformation may not be necessary or not appropriate; see [

20]. In our studies of this article, we consider such transformation inappropriate if there are too many zeros in DCD matrix because it indicates that the neighborhood of one single cell has no different other cell types.

SigClust: Statistical significance of clustering (SigClust) method is hypothesis test:

which can be used to determine whether any two clusters are significantly different or if we should put them together to be one cluster; see [

38,

39].

2.4. Proposed DCD-TMHC Computation Method

The HC method is well-known for being very computationally intensive, thus cannot handle our huge single-cell ST data even using the super-computer resources at University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill. On the other hand, the 2-means method can run the huge single-cell ST data with good computing speed. Thus, the basic idea of our proposed DCD-TMHC method is to use the 2-means method on the huge single-cell ST data consecutively until obtaining clusters small enough for the HC method to handle, then apply the HC method on each cluster. This allows us to use the HC method on the subsets of the huge single-cell ST data, which are identified by the 2-means method and verified by SigClust for their distinctiveness.

In practice, if the researchers have greater computation power, they can use the 2-means method fewer times to quickly get the clusters to be “not too big”, while if the researchers have smaller computation power, they need to use the 2-means method more times. Our proposed DCD-TMHC computation method is adaptive to handle the data of any large size, and it is described below as DCD-TMHC Computation Method:

- Step 1:

Process the single-cell ST data into DCD matrix, then, if appropriate, transfer it using Aitchison log-ratio transformation;

- Step 2:

Use the 2-means method consecutively to obtain clusters of not too big size as shown in

Figure 3, where SigClust is used to make sure that the split clusters are distinct, and any two non-distinct clusters are considered as one st-community;

- Step 3:

For distinct clusters obtained in Step 2, apply HC method as shown in

Figure 4, where SigClust is used on each large enough node of the dendrogram to determine whether the split should be kept: (a) if not or not large enough, stop at the node and treat it as one st-community; (b) if yes, continue SigClust down to the next node.

Figure 3.

Successive 2-Means Method.

Figure 3.

Successive 2-Means Method.

Figure 4.

Step 3 of DCD-TMHC Method.

Figure 4.

Step 3 of DCD-TMHC Method.

Remark 1. In real data analysis or in simulation studies, the “not too big” in Step 2 is determined by computation power, and “not large enough” in Step 3 uses a chosen number to stop at Step 3 (a). The studies in this article all used super computer at University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill. Moreover, Step 2 and related Figure 3 suggest an alternative clustering method, called successive 2-means

(STM) method, which keeps running Step 2 without ever going to Step 3 for running HC method. Such STM computation method stops at the node if it is “not large enough” for chosen or if one of its two split clusters has size less than a chosen number . In practice, the choice of radius is based on the discussion of Figure 2a,b at the end of Section 2.1 which ensures that the overwhelming disks contain total number of cells in the range of 20–60. For the choice of , we first visualize the data, such as real data example shown in Figure 2a or simulation data shown in Figure 5, then choose be a bigger number if the communities appear to be likely bigger size with same spatial and neighborhood pattern; and choose to be a smaller number if certain communities appear to be quite small. Moreover, the choice of number is selected based on how much smaller one of the two split clusters is based on 2-means clustering. 3. Simulation Studies

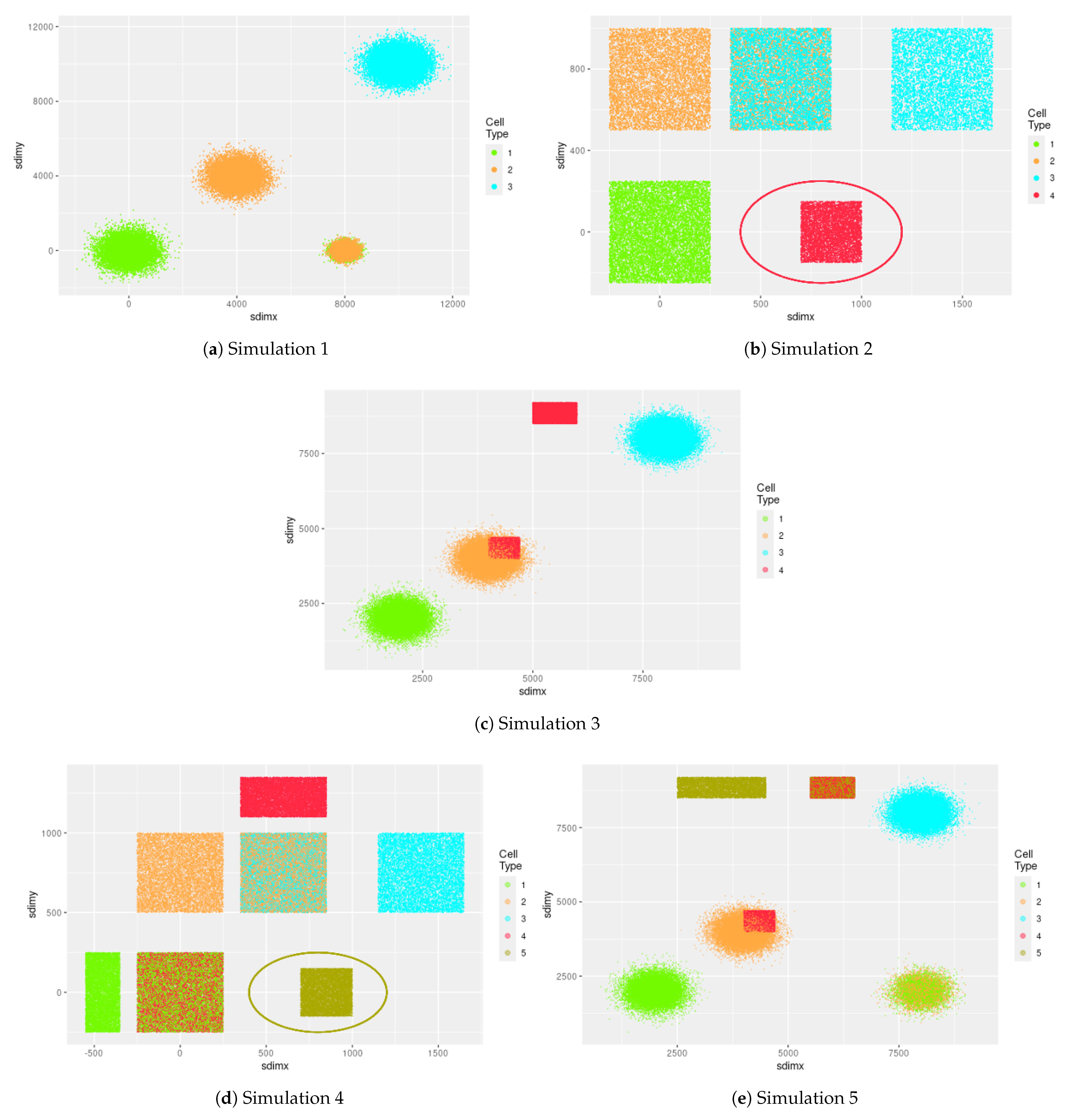

This section presents some simulation results on st-community detection using various existing methods listed in

Section 2 and our proposed DCD-TMHC computation method, plus the alternative STM method. There are 5 different simulation study settings which are summarized in

Table 1.

Figure 5 displays the visualization of these 5 simulation settings, and

Table 2a–e present the summary of simulation results.

In the setting of Simulation 1, there are 4 intended st-communities, each of which is in its own distinct spatial region. Each of three spatial regions has only one unique cell type present, while the 4th intended st-community has both cell type 1 and cell type 2 mixed together. The coordinates of location for each cell are generated by normal distributions. These st-communities are designed to represent different cell neighboring patterns found in single-cell ST data. The settings of Simulations 2–5 are similarly designed.

In

Table 1, we denote

as the discrete uniform distribution between positive integers

and

,

as the continuous uniform distribution with support interval

, and

as the normal distribution with mean

and variance

, where for simplicity, unit

is used for parameters of distribution notations. For each simulation setting, the number of cells is generated using the discrete uniform distribution listed on the top, except different discrete uniform distributions are used in ST-Community 4 of Simulation 1 and in ST-Community 7 of Simulation 5, respectively. For instance, notation “Cell 1 (12,462)” in ST-Community 1 of Simulation 1 means a total number of 12,462 Cell

is generated from

, where 10 and 25 represent 10,000 and 25,000, respectively. Also, under Simulation 2, notations “Cell 2 (50% = 7370)” in ST-Community 2 and “Cell 2 (50% = 7404)” in ST-Community 3 mean that 50% of the number generated from

for Cell Type 2 is used in ST-Communities 2 and 3, respectively.

For the 5 simulation settings in

Table 1, we first process the data into DCD matrix (

6), but Aitchison data transformation is not used here because the data contain too many zeros.

Table 2a–e only include simulation results for some existing clustering methods, our proposed DCD-TMHC computation method and alternative method STM, because HC method is too time-consuming, and methods such as Seurat, UMAP-Mclust, etc., are incompatible for compositional data. The parameters listed in

Table 2a–e are chosen based on our various experimental testings during the simulation studies.

Note that

Table 1 gives

intended st-community number

k for each simulation setting; thus

k is used for the

k-means and Mclust methods, while all other methods determine the number of st-communities on their own, and “NA” indicates no results available for certain methods.

Figure 5 displays the visualization of 5 simulation settings, which agrees with the actual intended st-community numbers of Simulations 1, 2 and 4. For Simulation 3, 5 is the intended st-community number, but

Figure 5c clearly shows that the actual st-community number is 7–8, because the region with overlapping colors of orange and red has some parts that are more dense than other parts, and the boundary between colors orange and red has some parts with solid orange surrounding red, while other parts have sparse orange surrounding red. Similarly, Simulation 5 has 7 as the intended st-community number, but

Figure 5e suggests that the actual st-community number is 9–10.

To check the accuracy of st-community detection, a good numerical measure is

Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) [

40], which ranges with values in interval

and has number close to 1 as an indication of high accuracy for st-community detection. In

Table 2a–e, the ARIs are computed for all listed methods assuming that the intended st-community numbers given in

Table 1 are true.

Remark 2. In Table 2a–e, our proposed DCD-TMHC method is obviously superior to all other methods because it consistently and correctly detects the actual st-community numbers, and it has the highest ARI for Simulations 1, 2 and 4, which give the accurate st-communities. But the ARI numbers in Table 2c,e for Simulations 3 and 5, respectively, do not represent the accuracy of st-community detection because the intended st-communities given in Table 1 are not the actual st-communities in these two cases. From the simulation results in Table 2a–e, it is easy to see that Gap k-means and HDBSCAN methods do not work well. Moreover, Mclust method does not work well either because without the given st-community number k, this method has 1–9 as the default st-community numbers and the finally determined st-community number is based on the highest BIC out of 14 different Gaussian mixture models; see Figure 6 for BIC plot under Simulation 1 setting, which gives 1 as the detected st-community number. For Simulation 2–5 settings, Mclust performs similarly as shown in Figure 6 for the setting of Simulation 1. In summary, the DCD data generated in simulation studies is very dense, thus the simulation results indicate that the existing clustering methods do not handle well very dense compositional data, such as single-cell ST data produced by CosMx, which is shown in real data analysis below. 4. CosMx Data Analysis

This section applies our proposed DCD-TMHC computation method, a few other methods and some CN methods to analyze a CosMx breast cancer dataset, which is a single-cell ST dataset and was produced by the CosMx machine at the NanoString Company (Bothell, WA, USA). The goal is to achieve st-community detection, then analyze its impact on cancer research.

The CosMx data under consideration here consists of eight samples from four people; each of them had one primary breast cancer sample and one metastasis sample. The total cell number from 8 samples is , and the total highly cancer research-related cell types under consideration are B-plasma, endothelial, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, macrophages, mast, normal-BEC, T, and tumor cells.

For each sample, cell types were manually annotated by the Leiden method and the expression of cell marker genes, and 19–25 FOVs were manually chosen for the purpose of having many tumor cells, as well as reflecting other cell types present in the data, such as normal breast epithelial (normal-BEC) cells, hepatocytes cells, etc.; see

Figure 1 for the description of FOVs, and see

Table 3 below for the data summary.

As the initial step of st-community detection, we use radius

to process the CosMx data

into DCD matrix

given by (

6) with

and

, which does not apply the disk given by (

4) centered by cell

’s too close to the boundary of FOV or too isolated. After applying Aitchison log-ratio transformation to matrix

, we use our proposed DCD-TMHC method, STM method, 10-means method, and Elbow

k-means method to detect st-communities; see the results displayed in

Figure 7a–d, which give the bar charts of

cell types for each detected st-community. A bar in each detected st-community represents the percentage of one cell type within that st-community.

In

Figure 7, Elbow

k-means method determines

, DCD-TMHC computation method uses

, and STM method uses

. In our analysis, we also consider DBSCAN method, which only detects two st-communities, thus the result is not included in

Figure 7. Other clustering methods, such as Gap

k-means, HDBSCAN, Mclust, etc., are also not included here due to the discussion given in Remark 2 about simulation results and their poor performance on this CosMx data

in our analysis.

In addition, some CN methods mentioned in

Section 1 are also considered to analyze the CosMx breast cancer data here, such as CNE [

16], CF-IDF [

41], SpatialLDA [

42], SPIAT [

43], and CytoCommunity [

44]. But they cannot handle the overly large data set here, except CNE and CF-IDF methods, both of which require a pre-chosen st-community number. It is interesting to notice that our proposed DCD-TMHC method detects 19 st-communities for the CosMx data, while Elbow

k-means method determines

st-communities. Thus, we use

as the chosen st-community number for CNE and CF-IDF. Due to the very poor performance of CF-IDF method, we only include the results of CNE-20 method in

Figure 7e.

To our best knowledge, among all existing spatial domain methods, only SpaDo method in [

45] can directly handle single-cell ST data. We use this SpaDo method to analyze the CosMx breast cancer data, but it also cannot handle the overly large dataset, thus no results from SpaDo method are included in

Figure 7.

Note that the detected st-communities among 5 methods displayed in

Figure 7 have some similarities and also some quite noticeable differences. Our DCD-TMHC method detects ST-Community 5 as having the highest percentage of tumor cells, 99.7%, in the st-community, while STM, 10-means, Elbow

k-means and CNE-20 methods detect ST-Communities 3, 5, 3 and 1 as having the highest tumor cell percentages 98.7%, 97.3%, 98.8% and 98.5%, respectively; thus they are quite similar; see

Table 4. On the other hand, for immune cell as the sum of B-plasma and T cells, the DCD-TMHC method detects ST-Community 19 as having the highest percentage of immune cells, 62.2%, in the st-community, while STM, 10-means, Elbow

k-means and CNE-20 methods detect ST-Communities 32, 8, 12 and 6 as having the highest immune cell percentages 48.0%, 27.4%, 50.6% and 87.0%, respectively, thus they are quite different; see

Table 5.

For many other differences among detected st-communities by different methods, a particularly noticeable one is that the DCD-TMHC method detects two ST-Communities, 8 and 14, as having the highest percentage of normal cells; the STM method detects two such ST-Communities, 26 and 40; and the CNE-20 method also detects two such ST-Communities, 8 and 12. But each of 10-means method and Elbow k-means method only identifies one such st-community: ST-Community 1 for the 10-means method and ST-Community 13 for the Elbow k-means method. Detecting two st-communities with the highest percentages of normal cells better reflects the existing heterogeneity of neighboring patterns of normal cells.

As mentioned in

Section 1 and 2, in [

15] for colorectal cancer and in [

34] for lung cancer, both used the 10-means method to detect st-communities based on their data. Schurch et al. [

15] associated certain st-communities with better survival for high-risk patients, while Enfield et al. [

34] identified certain st-community with a high percentage of current smokers which is highly associated with lung cancer. Thus, based on our detected st-communities in

Figure 7, we are interested in their impact on and association with cancer research as follows.

In

Table 4, for ST-Community 5 detected by our proposed DCD-TMHC method, each of 8 samples listed in

Table 3 has the following variables given in

Table 4:

where

is the total number of cells in sample

that belongs to ST-Community 5 detected by DCD-TMHC method,

is the total cell number in sample

, and the values of

’s in

Table 4 are

etc. Thus, this is a dataset observed for a binary response variable

Y and an explanatory variable

X, which is naturally analyzed using the following

logistic regression model: [

46,

47]

and logistic regression (LR) estimators

and

are computed based on data (

10) and given in

Table 4. In turn, the estimated logistic regression curve is

which is displayed as a red curve in

Figure 8. Note that

in Equation (

11) is the conditional probability of being primary breast cancer for given value

x, and above

is the estimated conditional probability of

.

For the rest of the data in

Table 4 produced by four methods of STM, 10-means, Elbow

k-means and CNE-20, we obtain four estimated logistic regression curves using Equations (

10)–(

12), respectively, and present them in

Figure 8 as well for comparison.

Similarly presented as

Table 4, the data in

Table 5 and

Table 6 are based on detected st-communities as having the highest percentages of immune cells and normal cells, respectively. Following Equations (

10)–(

12), we obtain estimated logistic regression curves for

Table 5 and

Table 6, and present them in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, respectively.

Remark 3. Logistic Regression Curves in Figure 8. From Equations (10)–(12), we see that in Figure 8, five estimated logistic regression curves based on the data in Table 4 are all decreasing functions, and the red curve based on the DCD-TMHC method’s detection of ST-Community 5 as having the highest percentage of tumor cells is located below all other four curves. The decreasing red curve means that for a sample with larger percentage of cells located in ST-Community 5, the patient with cancer tissue sample has less chance of being primary breast cancer due to the meaning of and given in Equations (11) and (12). From , the decreasing red curve also means that for a sample with larger percentage of cells located in ST-Community 5, the patient with cancer tissue sample has greater chance of being at metastasis of cancer, and our proposed DCD-TMHC method makes such assessment more sharply than all other four methods because the red curve by DCD-TMHC method being located below all other four curves in Figure 8 means that curve is located above all other four curves ; that is for the same large value of x, the red curve by DCD-TMHC method predicts the greatest chance of being at metastasis of cancer than all other four methods. Remark 4. Logistic Regression Curves in Figure 9 and Figure 10. From Remark 3 on the interpretation of Figure 8, we see clearly that in Figure 9, three estimated logistic regression curves, red , green and orange based on data in Table 5 via ST-Communities 19, 32 and 12 as having the highest percentages of immune cells detected by methods DCD-TMHC, STM and Elbow k-means, respectively, are all increasing functions, while the red curve by the DCD-TMHC method is located significantly above two curves and . This means that for a sample with large percentage of cells located in ST-Community 19 detected by DCD-TMHC method, the patient with cancer tissue sample has large chance of being primary breast cancer, and that for the same large value of x, the red curve by DCD-TMHC method predicts the greatest chance of being primary breast cancer than both STM method and Elbow k-means method. However, it should be noticed that the blue estimated logistic regression curve by the 10-means method and the brown estimated logistic regression curve by the CNE-20 method are slightly decreasing functions, which means that the 10-means method and CNE-20 method are not properly predictive. Thus, our proposed DCD-TMHC method has superior performance compared to all other methods for detecting immune cell related st-communities. In Figure 10, we see that all five estimated logistic regression curves based on the data in Table 6 are increasing functions, which are based on the st-communities as having the highest percentages of normal cells detected by 5 different methods. The curves and by DCD-TMHC and STM methods, respectively, are located quite closely, while curves and by the 10-means and Elbow k-means methods, respectively, are also located quite closely. The brown curve by the CNE-20 method is somewhat located in the middle of two groups. Since curves and are located significantly above curves and as well as being notably located above curve , we know that DCD-TMHC and STM methods perform better for the detected normal cell related st-communities. 5. Discussion and Conclusions

The single-cell ST data produced by recent biotechnologies, such as CosMx and Xenium machine, contain a huge amount of information about cancer tissue samples, which has great potential for the improvement of cancer diagnosis and treatment. This article reveals that many existing clustering methods perform poorly for st-community detection of single-cell ST data produced by CosMx, and the commonly used kNN compositional data method shows a lack of informative neighboring cell patterns for huge CosMx data. Thus, here we propose a novel and much more informative disk compositional data (DCD) method, which identifies the neighboring pattern of each cell based on nearby cell-percentages via taking into account of the features of single-cell ST data produced by recent new technologies.

After initial processing of the single-cell ST data into DCD matrix, an innovative and interpretable DCD-TMHC st-community detection method is proposed in this paper. Applying various existing methods as well as our DCD-TMHC computation method, extensive simulation studies and actual analysis of a CosMx breast cancer dataset show that our proposed DCD-TMHC method performs better than all other methods, including the existing and applicable CN methods or spatial domain methods.

Based on the st-communities detected by our proposed DCD-TMHC computation method for the CosMx breast cancer data, we use the logistic regression model to analyze the association and relationship between the identified st-communities of the CosMx data and cancer phenotypes. The results here demonstrate that our proposed DCD-TMHC method is better interpretable and superior to all other existing methods, especially in terms of assessment for primary cancer and metastasis cancer.

For upcoming research in the future, the novel, innovative, informative and interpretable DCD-TMHC computation method proposed in this article will be helpful and have an impact on future cancer research based on single-cell ST data. In particular, if we can use the new ST technologies to obtain more tissue samples from different types of cancer at different stages, then different types of st-communities can be detected and identified by our DCD-TMHC method for a specific type of cancer at a particular stage, which, by using the logistic regression model, appropriate generalized linear models, or other statistical models, such as weighted empirical likelihood method [

48,

49,

50], generalized latent proportional hazards model [

51], etc., can be applied to improve cancer diagnosis and monitor cancer treatment progress.