A Rare Case of First-Time Seizure Induced by Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Following the Use of Tranexamic Acid for Menorrhagia

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

| Parameter | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (Hb) | 77 g/L | 115–165 g/L |

| Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) | 69.9 fL | 79–100 fL |

| Ferritin | 11 µg/L | 13–150 µg/L |

| Serum Iron | 2 µmol/L | 5.8–34.4 µmol/L |

| Transferrin Saturation | 3% | 20–55% |

| Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) | 72 µmol/L | 45–72 µmol/L |

| White Cell Count (WCC) | 16.5 × 109/L | 4.0–11.0 × 109/L |

| Neutrophils | 13.9 × 109/L | 1.7–7.5 × 109/L |

| Platelets | 363 × 109/L | 150–400 × 109/L |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | 16.3 mg/L | <5 mg/L |

| Lactate (Blood Gas) | 4.9 mmol/L | 0.5–2.2 mmol/L |

3. Discussion

3.1. Pathophysiology of TXA-Induced CVST

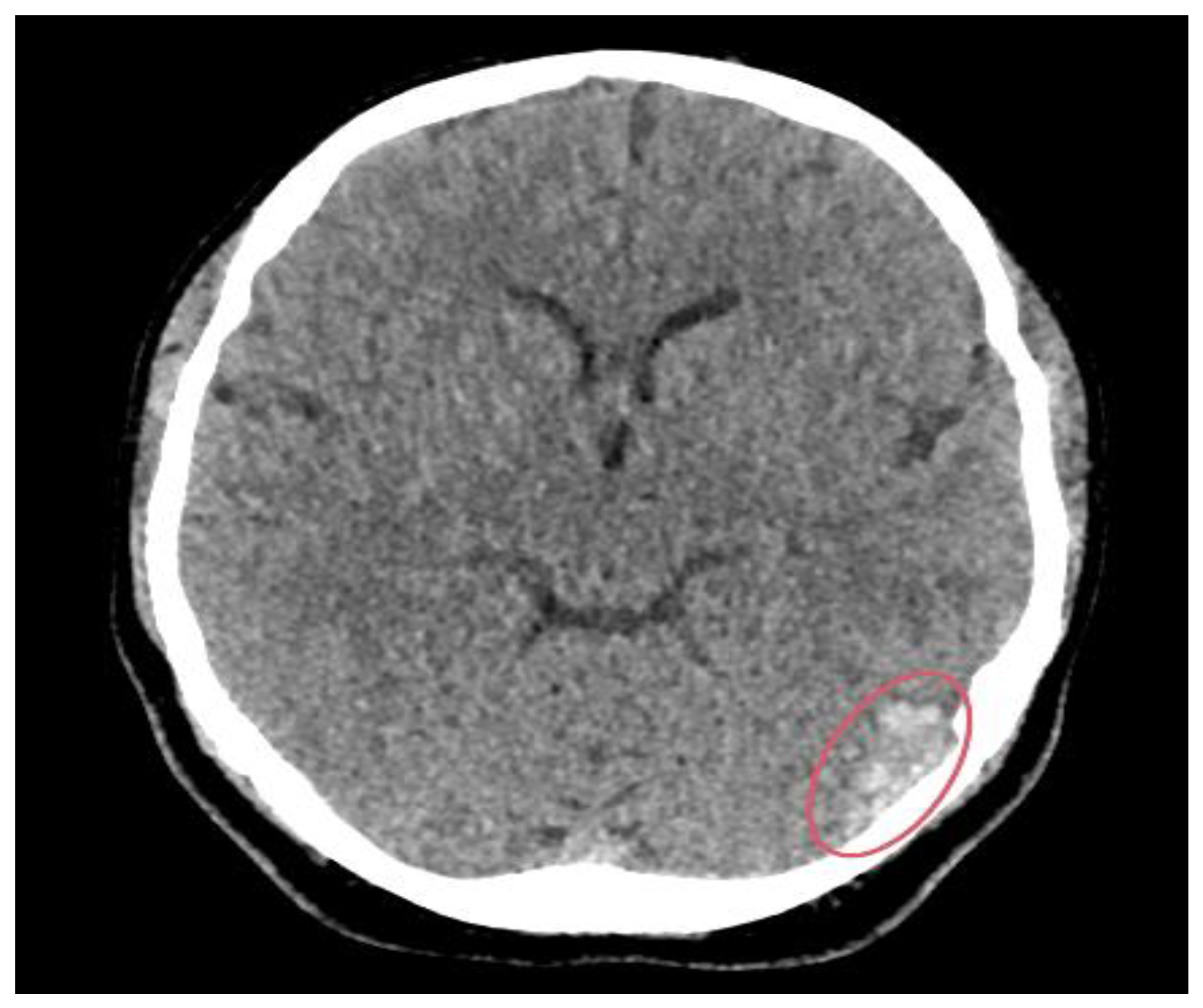

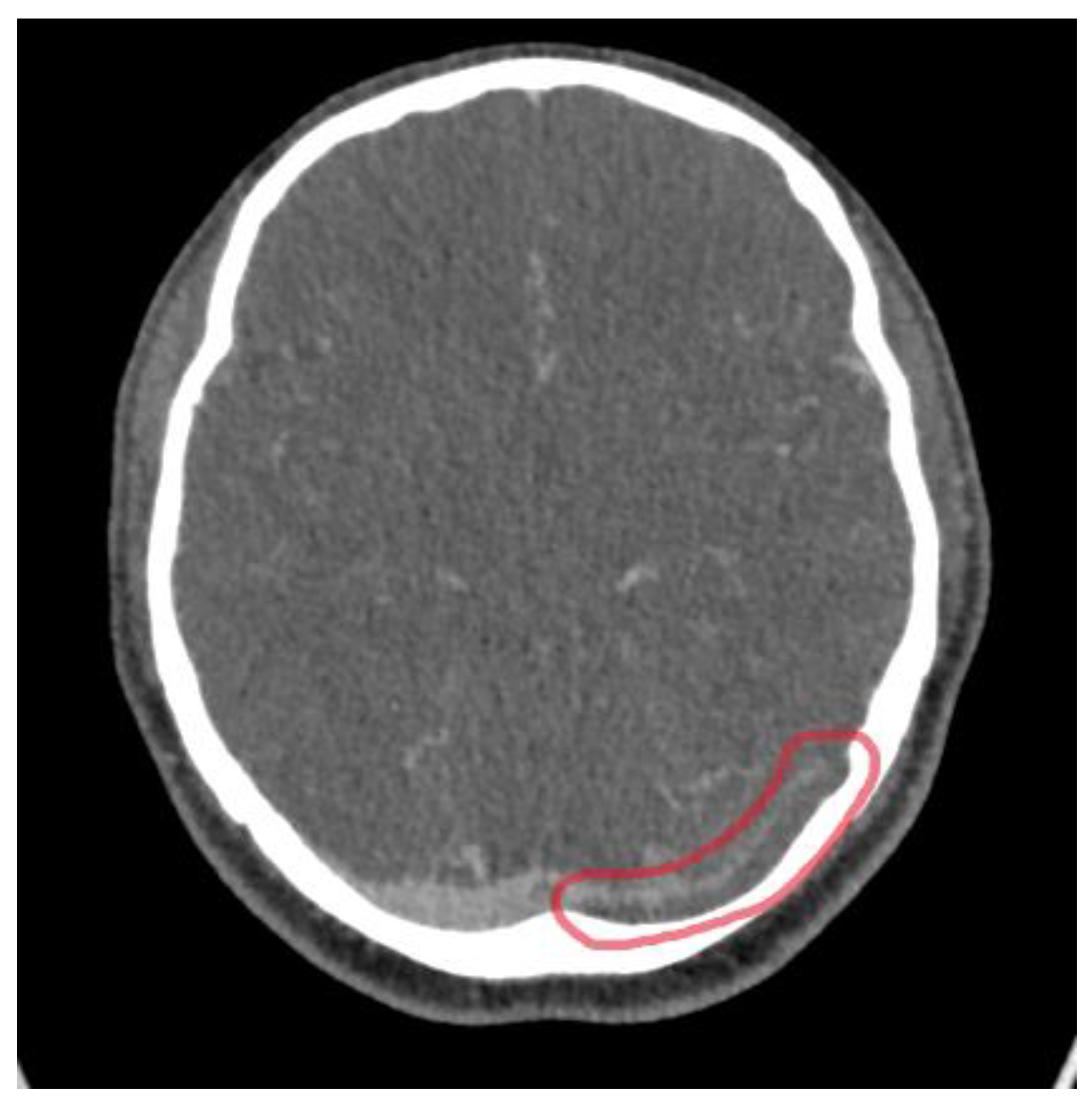

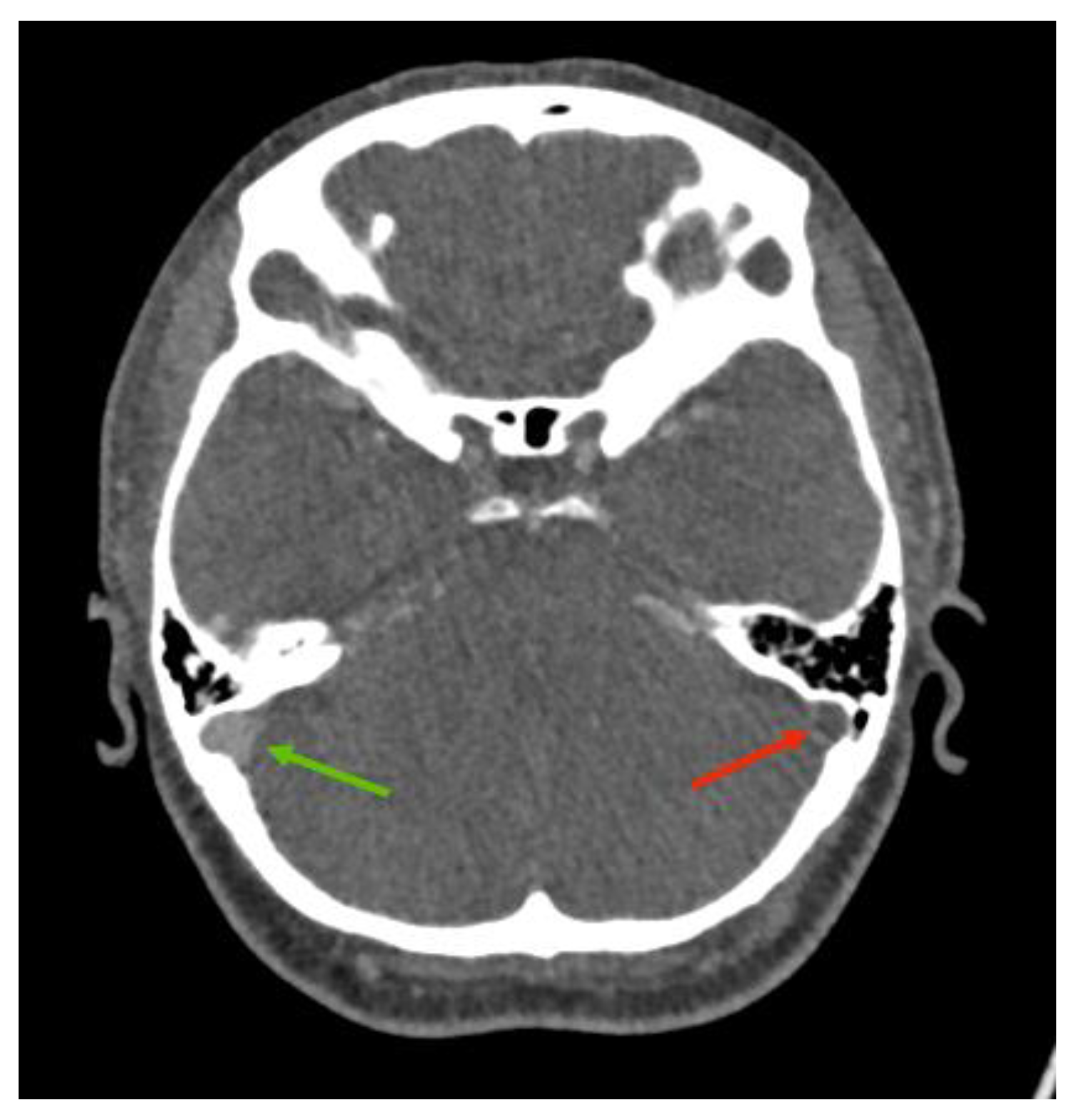

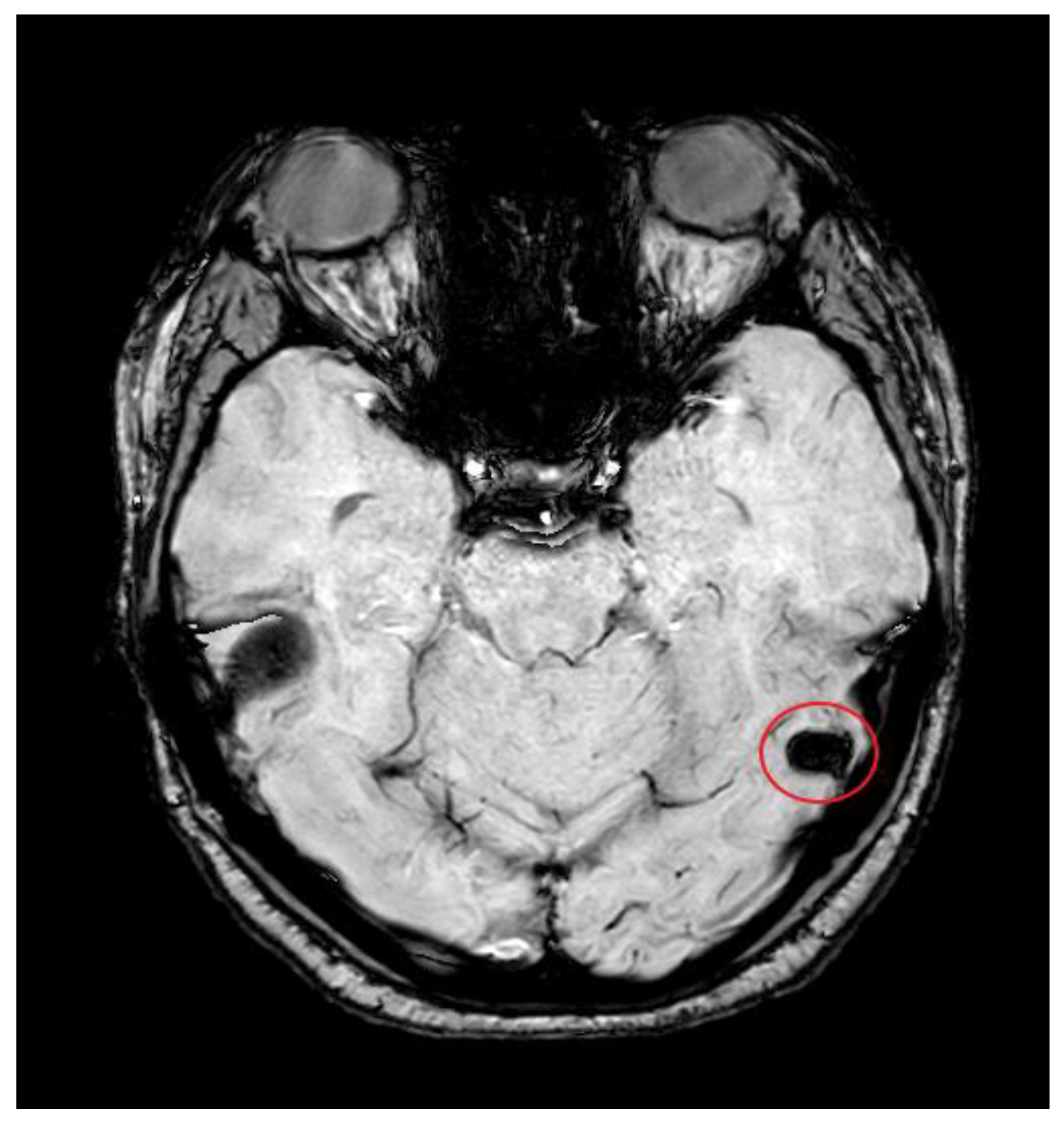

3.2. Imaging Role

3.3. Management Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barseghyan, M.; Chae-Kim, J.; Catherino, W.H. The efficacy of medical management of leiomyoma-associated heavy menstrual bleeding: A mini review. F&S Rep. 2024, 5, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauncey, J.M.; Wieters, J.S. Tranexamic Acid. [Online] Nih.gov. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532909/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hunt, B.J. The current place of tranexamic acid in the management of bleeding. Anaesthesia 2014, 70, 50-e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakur, H.; Roberts, I.; Fawole, B.; Chaudhri, R.; El-Sheikh, M.; Akintan, A.; Qureshi, Z.; Kidanto, H.; Vwalika, B.; Abdulkadir, A.; et al. Effect of Early Tranexamic Acid Administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and Other Morbidities in Women with post-partum Haemorrhage (WOMAN): An international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murao, S.; Nakata, H.; Roberts, I.; Yamakawa, K. Effect of tranexamic acid on thrombotic events and seizures in bleeding patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtmüller, R.; Schlag, M.G.; Berger, M.; Hopf, R.; Huck, S.; Sieghart, W.; Redl, H. Tranexamic Acid, a Widely Used Antifibrinolytic Agent, Causes Convulsions by a γ-Aminobutyric AcidA Receptor Antagonistic Effect. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 301, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecker, I.; Wang, D.-S.; Romaschin, A.D.; Peterson, M.; Mazer, C.D.; Orser, B.A. Tranexamic acid concentrations associated with human seizures inhibit glycine receptors. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4654–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeuber, I.; Weibel, S.; Herrmann, E.; Neef, V.; Schlesinger, T.; Kranke, P.; Messroghli, L.; Zacharowski, K.; Choorapoikayil, S.; Meybohm, P. Association of intravenous tranexamic acid with thromboembolic events and mortality. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, e210884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaopo, E.O.; Ijaopo, R.O.; Adjei, S. Bilateral pulmonary embolism while receiving tranexamic acid: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 14, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaidi, A.; Mørch, L.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Lidegaard, O. Oral tranexamic acid and thrombosis risk in women. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 35, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, S.P.; Mallick, P.N.; Jagia, M.; Singh, R.K.A. Acute arterial thrombosis associated with inadvertent high dose of tranexamic acid. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 17, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowlton, L.M.; Arnow, K.; Trickey, A.W.; Sauaia, A.; Knudson, M.M. Does tranexamic acid increase venous thromboembolism risk among trauma patients? A prospective multicenter analysis across 17 level I trauma centers. Injury 2023, 54, 111008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacinti, D.; Cartocci, G.; Colonnese, C. Cerebral venous thrombosis: A case series and a neuroimaging review of the literature. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 58, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperzel, M.; Huetter, J. Evaluation of aprotinin and tranexamic acid in different and models of fibrinolysis, coagulation and thrombus formation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 2113–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengborn, L.; Blombäck, M.; Berntorp, E. Tranexamic acid—An old drug still going strong and making a revival. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: Results of international multicentre case-control study. Lancet 1995, 346, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartfield, D.S.; Lowry, N.J.; Keene, D.L.; Yager, J.Y. Iron deficiency: A cause of stroke in infants and children. Pediatr. Neurol. 1997, 16, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadi, P.; Behgam, B.; Baruffi, S. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. [Online] PubMed. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459315/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Schaller, B.; Graf, R. Cerebral Venous Infarction: The Pathophysiological Concept. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2004, 18, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibabadi, J.M.; Saadatnia, M.; Tabrizi, N. Seizure in cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. Epilepsia Open 2018, 3, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, J.M.; Canhão, P.; Stam, J.; Bousser, M.-G.; Barinagarrementeria, F. Prognosis of Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis. Stroke 2004, 35, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2Saposnik, G.; Barinagarrementeria, F.; Brown, R.D.; Bushnell, C.D.; Cucchiara, B.; Cushman, M.; deVeber, G.; Ferro, J.M.; Tsai, F.Y. Diagnosis and Management of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Stroke 2011, 42, 1158–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lee, H.; Zhao, H.; Ding, Y.; Duan, J. Inflammation and Severe Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 873802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Overview|Venous Thromboembolic Diseases: Diagnosis, Management and Thrombophilia Testing|Guidance|NICE. 2020. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Sader, N.; de Lotbinière-Bassett, M.; Tso, M.K.; Hamilton, M. Management of Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 29, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Diagnosis and Assessment of Epilepsy|Epilepsies in Children, Young People and Adults|Guidance|NICE. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng217/chapter/1-Diagnosis-and-assessment-of-epilepsy (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Meirow, D.; Rabinovici, J.; Katz, D.; Or, R.; Ben-Yehuda, D. Prevention of severe menorrhagia in oncology patients with treatment-induced thrombocytopenia by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist and depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate. Cancer 2006, 107, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.H.; Lethaby, A. Pre-operative endometrial thinning agents before endometrial destruction for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Day | Clinical Event/Symptom | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Day 7 | Initiation of TXA | 1 g TDS started for menorrhagia; first 4-day course completed without symptom relief. |

| Day 4 | Second course of TXA begun | Another 3-day course prescribed (same dose) due to ongoing bleeding. |

| Day 3 | Headache onset | Described as “worst headache of life”—left-sided, throbbing, 10/10, radiating to neck. Associated with nausea, floaters, blurred vision, and neck stiffness. |

| Day 0 | Seizure and hospital presentation | Generalised tonic–clonic seizure while driving; no neurologic deficit post-ictal. Brought to the emergency unit. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bandt, J.; Oisakede, E.O.; Walker, N. A Rare Case of First-Time Seizure Induced by Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Following the Use of Tranexamic Acid for Menorrhagia. Reports 2025, 8, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040210

Bandt J, Oisakede EO, Walker N. A Rare Case of First-Time Seizure Induced by Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Following the Use of Tranexamic Acid for Menorrhagia. Reports. 2025; 8(4):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040210

Chicago/Turabian StyleBandt, Jennifer, Emmanuel O. Oisakede, and Natalie Walker. 2025. "A Rare Case of First-Time Seizure Induced by Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Following the Use of Tranexamic Acid for Menorrhagia" Reports 8, no. 4: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040210

APA StyleBandt, J., Oisakede, E. O., & Walker, N. (2025). A Rare Case of First-Time Seizure Induced by Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Following the Use of Tranexamic Acid for Menorrhagia. Reports, 8(4), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040210