Cooperative Air–Ground Perception Framework for Drivable Area Detection Using Multi-Source Data Fusion

Highlights

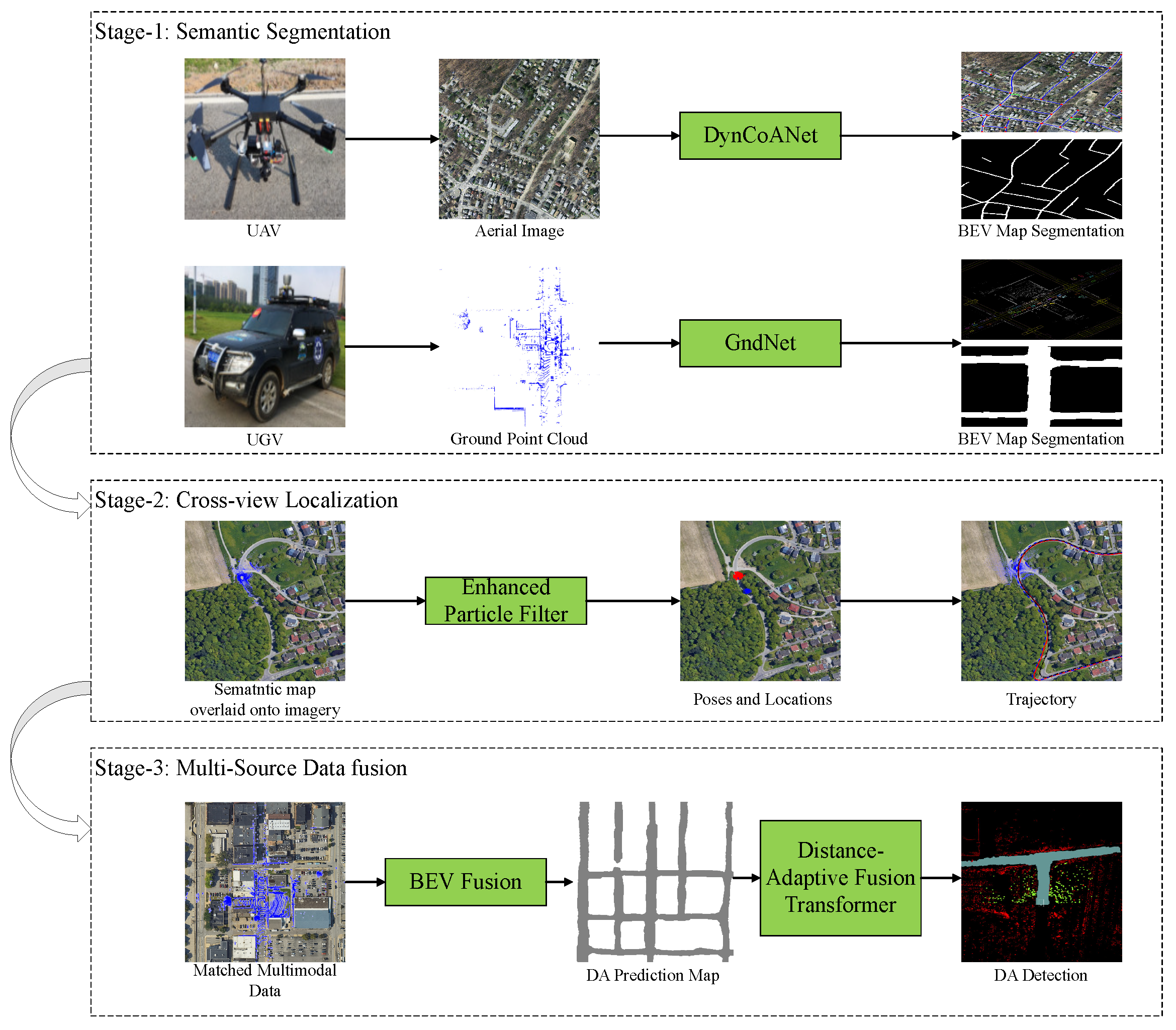

- We propose a novel three-stage cooperative air–ground perception framework that synergistically integrates UAV topological reasoning, robust cross-view semantic localization, and adaptive multimodal fusion for robust drivable area detection.

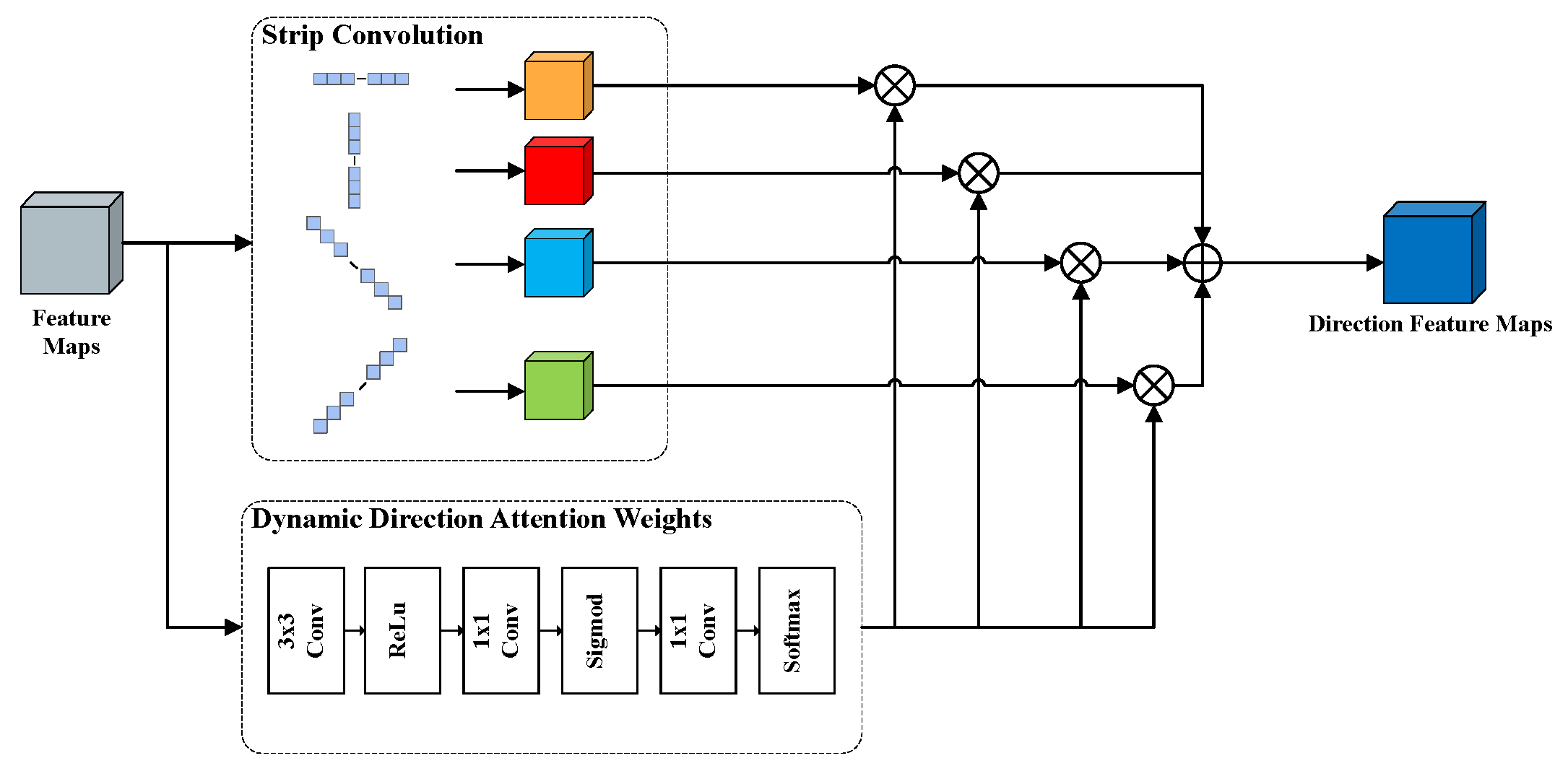

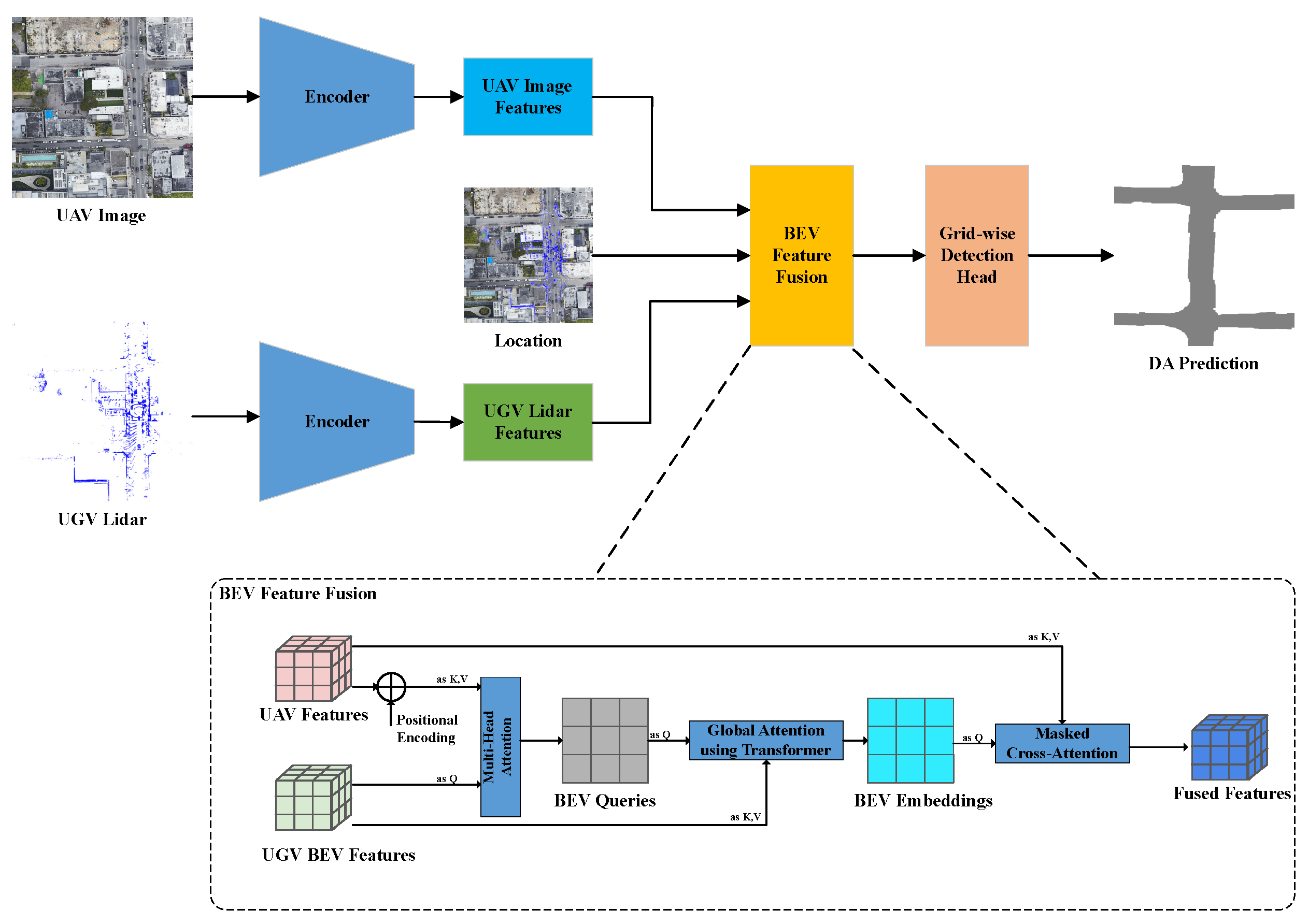

- The framework introduces three key innovations: a topology-aware segmentation network (DynCoANet), a semantic-enhanced particle filter for precise alignment, and a distance-adaptive fusion transformer (DAFT) for confidence-aware feature fusion.

- This work establishes that the tight co-design of perception, localization, and fusion modules is essential for autonomous systems to achieve robustness against occlusions and sensor limitations in complex environments.

- The presented framework provides a practical and effective solution for enhancing the safety and reliability of unmanned ground vehicles in challenging real-world transportation scenarios, such as unstructured roads and unregulated intersections.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Semantic Segmentation

2.2. Cross-View Localization

2.3. Drivable Area Detection

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Framework

3.2. Stage One: Semantic Segmentation for Topology Extraction

3.3. -View Semantic Localization

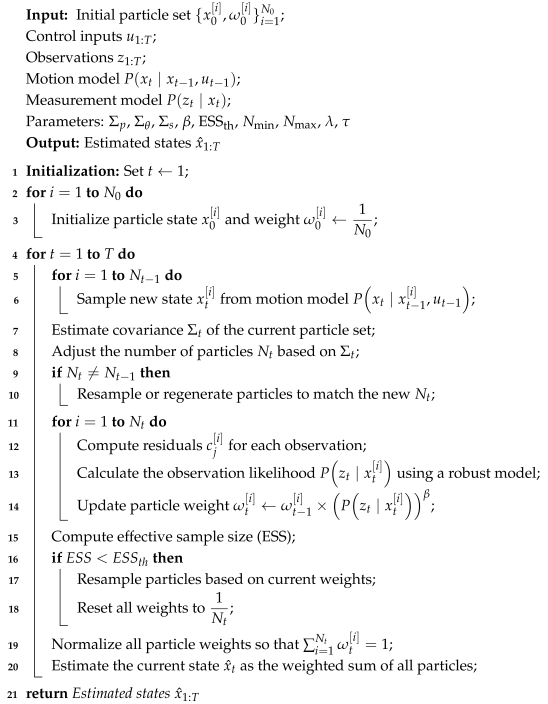

| Algorithm 1: Enhanced Particle Filter for Mobile Robot Localization. |

|

3.4. Stage Three: Drivable Area Detection

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Semantic Segmentation

4.2. Cross-View Localization

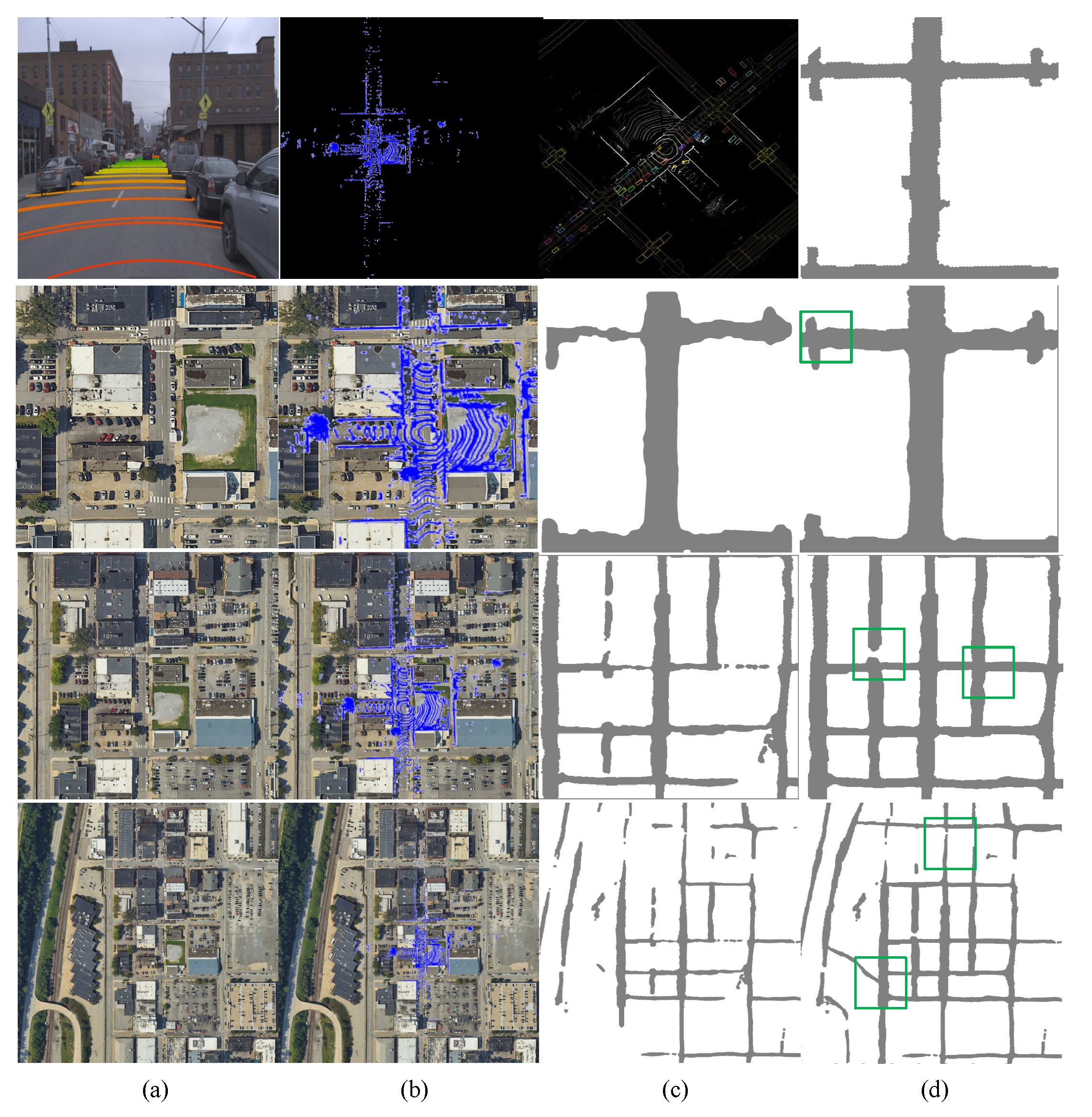

4.3. Drivable Area Detection

4.4. Real-World Experimental Validation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, H.; Fu, H.; Ren, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Fan, Y.; Dai, B. LiDAR-based drivable region detection for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1110–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, X.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, J.; Huang, K. LiDAR based traversable regions identification method for off-road UGV driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 3544–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, Y. LiDAR–camera fusion for road detection using a recurrent conditional random field model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, K.; Song, W.; Fu, M. Aerial-ground collaborative continuous risk mapping for autonomous driving of unmanned ground vehicle in off-road environments. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 9026–9041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wu, Z.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D. Collaborative semantic understanding and mapping framework for autonomous systems. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2020, 26, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Fan, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, G.; Zhang, Z. Opensatmap: A fine-grained high-resolution satellite dataset for large-scale map construction. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 59216–59235. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.; Li, B.; Wu, T. Off-road drivable area detection: A learning-based approach exploiting lidar reflection texture information. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liang, H.; Wang, Z.; Lin, L. A framework for drivable area detection via point cloud double projection on rough roads. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 102, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortelano, J.L.; Villagrá, J.; Godoy, J.; Jiménez, V. Recent developments on drivable area estimation: A survey and a functional analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, I.D.; Cladera, F.; Smith, T.; Taylor, C.J.; Kumar, V. Air-Ground Collaboration with SPOMP: Semantic Panoramic Online Mapping and Planning. IEEE Trans. Field Robot. 2024, 1, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.D.; Cladera, F.; Smith, T.; Taylor, C.J.; Kumar, V. Stronger together: Air-ground robotic collaboration using semantics. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 9643–9650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.D.; Alarabi, L.; Basalamah, S. DSMSA-Net: Deep spatial and multi-scale attention network for road extraction in high spatial resolution satellite images. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 1907–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, F.; He, S.; Abbar, S.; Alizadeh, M.; Balakrishnan, H.; Chawla, S.; Madden, S.; DeWitt, D. Roadtracer: Automatic extraction of road networks from aerial images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4720–4728. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gan, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, L. Rngdet: Road network graph detection by transformer in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, M. D-LinkNet: LinkNet with pretrained encoder and dilated convolution for high resolution satellite imagery road extraction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, R. RADANet: Road augmented deformable attention network for road extraction from complex high-resolution remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Li, R.J.; Gao, W.; Cheng, M.M. CoANet: Connectivity attention network for road extraction from satellite imagery. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 8540–8552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S. HARNU-Net: Hierarchical attention residual nested U-Net for change detection in remote sensing images. Sensors 2022, 22, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shen, Q.; Deng, Z.; Cao, X.; Wang, X. Absolute pose estimation of UAV based on large-scale satellite image. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.D.; Cowley, A.; Konkimalla, R.; Shivakumar, S.S.; Nguyen, T.; Smith, T.; Taylor, C.J.; Kumar, V. Any way you look at it: Semantic crossview localization and mapping with lidar. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 2397–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Peng, H.; Hu, J.; Bao, H.; Zhang, G. From Satellite to Ground: Satellite Assisted Visual Localization with Cross-view Semantic Matching. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 3977–3983. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S.; Leung, V.C. Energy-efficient ground traversability mapping based on UAV-UGV collaborative system. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2021, 6, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shan, J.; Liu, Y. Approximate Inference Particle Filtering for Mobile Robot SLAM. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Li, H. Beyond cross-view image retrieval: Highly accurate vehicle localization using satellite image. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17010–17020. [Google Scholar]

- Charroud, A.; El Moutaouakil, K.; Yahyaouy, A.; Onyekpe, U.; Palade, V.; Huda, M.N. Rapid localization and mapping method based on adaptive particle filters. Sensors 2022, 22, 9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Amini, A.; Yang, X.; Mao, H.; Rus, D.L.; Han, S. Bevfusion: Multi-task multi-sensor fusion with unified bird’s-eye view representation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 23–26 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 2774–2781. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Fu, J.; Shen, Y.; Jing, H.; Chen, S.; Zheng, N. Complementing onboard sensors with satellite maps: A new perspective for HD map construction. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 11103–11109. [Google Scholar]

- Man, Y.; Gui, L.Y.; Wang, Y.X. Bev-guided multi-modality fusion for driving perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 21960–21969. [Google Scholar]

- Goenawan, C.R.; Paek, D.H.; Kong, S.H. See the Unseen: Grid-Wise Drivable Area Detection Dataset and Network Using LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Xian, R.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Elnoor, M.; Song, D.; Manocha, D. AGL-NET: Aerial-ground cross-modal global localization with varying scales. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; p. 8161. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fu, H.; Tai, C.L. Transfusion: Robust lidar-camera fusion for 3d object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1090–1099. [Google Scholar]

| Model | IoUroad | MIoU (%) | F1 (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Inference (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-LinkNet [15] | 57.62 | 63.00 | 77.11 | 76.69 | 77.53 | 71 |

| RoadCNN [13] | 59.12 | 65.49 | 79.08 | 78.14 | 80.04 | 28 |

| CoANet [17] | 59.11 | 69.42 | 81.22 | 78.96 | 83.61 | 22 |

| Ours | 61.14 | 78.49 | 87.67 | 86.45 | 88.93 | 45 |

| Method | kitti0 | kitti2 | kitti9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original [20] | 2.0 | 9.1 | 7.2 |

| Ours | 1.7 | 8.2 | 6.4 |

| ROI Size | Grid-DATrNet | DAFT (Ours) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 Score | Inference | Computation | Accuracy | F1 Score | Inference | Computation | |

| (%) | (ms) | (GFLOPS) | (%) | (ms) | (GFLOPS) | |||

| 120 m × 100 m | 93.28 | 0.8328 | 231 | 142 | 94.45 | 0.8426 | 262 | 157 |

| 200 m × 200 m | 88.35 | 0.7732 | 324 | 182 | 90.72 | 0.8014 | 306 | 178 |

| 400 m × 400 m | 75.42 | 0.6588 | 502 | 268 | 83.84 | 0.7349 | 455 | 236 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Liang, H.; Zhou, P. Cooperative Air–Ground Perception Framework for Drivable Area Detection Using Multi-Source Data Fusion. Drones 2026, 10, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020087

Zhang M, Liang H, Zhou P. Cooperative Air–Ground Perception Framework for Drivable Area Detection Using Multi-Source Data Fusion. Drones. 2026; 10(2):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020087

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mingjia, Huawei Liang, and Pengfei Zhou. 2026. "Cooperative Air–Ground Perception Framework for Drivable Area Detection Using Multi-Source Data Fusion" Drones 10, no. 2: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020087

APA StyleZhang, M., Liang, H., & Zhou, P. (2026). Cooperative Air–Ground Perception Framework for Drivable Area Detection Using Multi-Source Data Fusion. Drones, 10(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020087