1. How to Help Children (Not) to Hate Books

Come siaiutai bambini a odiare i libri (literally

How to help children hate books) was the title Pinin Carpi gave to an article he wrote for the

Altra Città (

Other city) magazine in 1974, where he described the state of publications for children in Italy at the time. To write it, he described a scene he had witnessed personally some time before at a railway station in Milan: “I wish to tell about an episode I witnessed not long ago. In front of a newsstand in the station, a little boy was looking at the comics on sale there. Beside him, his father urged him to choose one. “Well, make up your mind, what you want!?” Uncertain, the child selected one saying, “This one”. Immediately his father burst out, “Not that one! That one’s silly! This one is all right”, choosing another substantially identical one. It was clear that the child had made his choice on the basis of something in the comic which attracted him. It was equally clear that his father had not made the slightest effort to understand the reason for his son’s choice nor had he even tried to avail of the chance to satisfy his child. He had acted on the sole resentful conviction that children cannot understand what they want and that only the decision of an adult, whatever it may be, is the right one” [

1].

Carpi held that when publishers of books for children drew up their catalogues they had this precise view in mind, the basic presuppositions of which they shared and approved. “In actual fact”, he continued, “with some rare exceptions, books for children published in Italy are ugly, have a negative educational impact, are often harmful and off-putting. Generally speaking, the publisher and, as a result, the director of a series, consider the market, not the children. Who chooses books for children?—Carpi asked—Fathers, mothers, uncles, aunts etc., not the children themselves. What are the preferences, the tastes of these adult buyers? It is to them we need to sell the books. The children will just have to make do” [

1].

The dearth and poor quality of the books produced for children in Italy appeared to the author even more evident when compared to the publications for children available in other countries like England, France and Germany, where, while not disregarding the demands of the market, they were “varied, plentiful and far superior to ours” [

1]. Rather than due to a public of low-income, poorly educated parents, devoid of the tools necessary for the purchase quality books, Carpi attributed the cause of this situation to the publishers, “who, in order to sell at all costs, circulate senseless, very badly illustrated, trivial, unreliable books, full of inaccuracies and written in such a way that children fail to understand anything; if children read them on their own, not only do they fail to understand but are also prompted not to read, a refusal that may last a lifetime” [

1]. The main shortcomings, according to Carpi, were to be found in books for early childhood—admitted that publishers took the trouble of indicating age ranges on the books—where, he stressed, “Except for books by

EdizioniEmme, some of those belonging to the

Tantibambini series edited by Munari for

Einaudi, and very few others, the picture is black indeed. Yet (...) it is during early childhood that, not the child, but the man is formed. Already at the age of two, children are ready to fill their eyes with images: a book full of simple, recognizable pictures is capable of delighting them for a considerable length of time, but how many of these are available on the market? And what are the ones there actually are like? The three-year-old should have access to simple illustrated stories. But how are the few books available contrived? Of how many negative elements do they avail themselves?” [

1].

“On the one hand, economic exigencies make publishing a matter of business, rather than a cultural fact, on the other the Crocian prejudice which relegated books for children to the category of “non-poetry”, therefore “non-literature”, had, according to this writer, such an impact that they caused a lack of attention by literary criticism to publications for children, which—Carpi continued—is necessarily “non-poetry” if one accepts the idea that children are devoid of emotions, feelings and logic (different from that of adults, but well-articulated, nonetheless). Apart from these considerations, however, we need to be aware that in order to write illustrate, create a book for children, it is not sufficient to love them, even understand them; one has to place oneself upon their level as well as on their side, trying to imagine and feel like them, using their language and, above all, eliminating, as far as one can, adult presumption. Publishers and directors of series, too, should impose this upon themselves. Some chance!” [

1].

Pinin Carpi certainly knew—because he mentioned it—that in that very same city, Milan, where he had witnessed the episode which had inspired him for some time, since 1966 in fact, there was a publishing house working to provide children, from earliest childhood on, with the of literature he advocated: books made for small hands and small eyes to explore and touch; books telling stories in words and pictures capable of meeting the ability of very small children to understand narratives close to their own world, with which they would be able to identify. That publishing house was Emme Edizioni.

2. Reading before Learning to Read? Or the Promotion of Preschool Reading

“Our books for children—states a veritable poetical declaration issued by the publishing house in 1976—are based mainly on images because children’s thinking is predominantly visual; in our books the graphic aspect, the originality of the sign, colour, imagination, alternation between the real and the magical, are meant to meet the deeper needs of the world of children. We have done our utmost to make sure that our books are in tune with that world, and have paid the same attention to these books as we always have to our best books for adults. It is our intention, therefore, to ensure that books may enter into the life of the child, effortlessly, not as an “object of erudition”, but as a stimulus to the acquisition of experience and knowledge” [

2].

The challenge was that, in Italy back then (when there was still no serious talk of promoting reading, let alone books or picture books for early childhood) children could and ought to begin reading “before learning to read”. The true innovatory idea was, Archinto, herself believes “the revolutionary one of a literature for very small children: books destined for preschool children and which they could read even without the mediation of the adult” [

3].

Rosellina Archinto recalls the enormous difficulties encountered when trying to place this type of literature in environments run by “experts”; libraries and bookshops, where librarians and booksellers did not fully appreciate the significance of this cultural operation, so that it was rare to have our books accepted by the former and placed on shelves by the latter. Nor did the writers of scholarly essays pay proper attention to the issue and were not to do so for quite some time. Yet, a handful of small houses which published books for children, like Emme—one also recalls the La Coccinella house, directed by Loredana Farina, who from 1977 on, produced “the books with the holes” and the Fatatrac series for toddlers called Che senso ha (What’s the meaning)—had been committed to moving in that direction for quite some time.

Academic pedagogical studies of preschool-age reading in Italy, such as to raise those insights and courageous undertakings to scholarly status were very few and far between. It is significant to note that the first interesting research-results on the issue,

Capire le storie. Un modo di usare I racconti illustrate nella scuola dell’infanzia (

Understanding stories. A way of using illustrated stories at nursery school) by Lucia Lumbelli and Margherita Salvadori [

4] were published in 1977, in a series issued by

Emme Edizioni called

Il Puntoemme, the direction of which Rosellina Archinto entrusted to Graziano Cavallini, full professor of pedagogy at the universities of Bologna, Sassari and Milano. It was not until the 1980’s, however, and this probably due to the spread of specific sections for toddlers in libraries and reading-promotion initiatives, that criteria for the classification of books for children were drawn up [

5]: the definition “

picture book suitable for the first and second stages of early childhood and for the first stage of primary education” appeared in

Segnalibro, the

Schedario annual for 1988 [

6]; number 17, 1992 of the magazine

Liber contained the definition “

picture books and stories” [

7], while “book by images” or “story book”, depending on the quantity of the words contained in the book, was the classification proposed by the municipal authority of Reggio Emilia in 1980 (As regards “

picture books” these are said to be “(books) where the pictures act as the narrative support, independently of the presence or absence of words. Children who cannot read words, find adequate responses to their interests in the pictures. The “story-telling” book contains a text that needs to be read out loud by an adult while she and the child look at the pictures together.) [

8].

This genre of literature for children is rarely mentioned or treated in literary textbooks or histories of literature of the time: even when it does appear—in any case not before the 1980’s—the picture book is dealt with only superficially. Cibaldi, in his

Criteri di scelta e di valutazione del libro per l’infanzia (

Criteria by which to choose and appraise books for children) published by

La Scuola, Brescia, in 1955 and reissued several times afterwards (1961, 1966, 1968 and 1973), still posed the problem of justifying the existence of a literature for children and of providing a definition of it: “All the various pages of narrative that children have been shown to appreciate and that have appeared and appear to us to be qualified to educate, are classed under the name of literature for children. (...) Therefore, we will define as literature for children that plethora of works capable of felicitously promoting education on the basis of the psychological age of the child” [

9] (pp. 37–38) wrote Cibaldi. While mentioning the “illustrated” genre, the author provided no definition for it, however, not even in the “summary” which supplemented the volume, where, for each of the “kinds” of children’s literature he deemed existed, he provided a label: fairy tale, folk tale, adventure story, didactic narrative while he mentioned only authors traditionally identified as classics like Basile, Perrault, Grimm, Andersen, Barrie, Lorenzini, Carroll, Capuana. No names of authors of contemporary

picture books were listed. Antonio Lugli, for example, in his

Libri e figure. Storia della letteratura per l’infanzia e per la gioventù (

Books and pictures. A history of literature for children and young people), published by

Cappelli, Bologna in 1982, under the heading

Glialbi (

Albums) a sub-chapter of the chapter dedicated to

I contemporanei (

Contemporaries), after a short introduction, wrote, “In recent years in Italy, too, publishers have produced albums for the very young” [

10] (p. 244), he merely provides a descriptive bibliography which does not prompt any deep reflection on the issue of pre-school reading. Among others he mentions several titles from

Emme’s catalogue (although the publisher is never mentioned expressly):

La mela e la farfalla (

The apple and the butterfly) and

L’uovo e la gallina (

The egg and the chicken) by Iela ed Enzo Mari;

Gli animali del prato (

Field animals) by Iela Mari;

Un baco molto affamato (

The very hungry caterpillar) and

La coccinella sempre arrabbiata (

The eternally angry ladybird)

by Eric Carle;

Piccolo blu e piccolo giallo (

Little blue and little yellow)

Alessandro e il topo meccanico (

Alexander and the wind-up mouse) and

Guizzino (

Swimmy) by Leo Lionni, and also some works by Loredana Farina for

AMZ:

Le avventure di un orsetto (

The adventures of a little bear);

Melad’oro: favola bulgara (

Golden apple, a Bulgarian tale);

Raggi d’oro: leggenda alpine (

Golden rays, a legend from the Alps). This excursus ended with a brief presentation of a new publishing house called

Fatatrac (A. Lugli writes that “

Fatatrac is not exactly a publishing house for children, although it is actually; it brings together a group of young people dedicated to designing books for nursery and primary schools and has published several

picture books illustrated by a team of artists and text writers; some of these books are funny, some paradoxical and grotesque, some are toys, like those dealing with the senses (

Roba da nasi (

Nose stuff), 1978;

Occhio per occhio (

Eye for eye), 1979;

Acqua in bocca, (literally it means

Water in the mouth, but the real meaning is

Mum’s the word) 1980) with texts by Aldo De Bono, Paolo Fiumi, Matteo Faglia, Adriano Conte, etc.; like the tangram playing cards by Roberto Luciani (

La donna cheseminailgrano(

The woman who sows con), 1980), the

Pochestorie (

Few stories) series (

Raccontamela ancora(

Tell it again]by Aldo Pettini and Marta Bellagamba, 1981;

Il filo del racconto (

The plot), by Francesca Lazzarato and Patrizia Zerbi, 1981), besides posters, calendars etc.”.) [

10] (p. 245).

It was only between the end of the 1980’s and beginning of the 1990’s that histories of literature and of illustrations for children began to give the space they deserved to publishing houses that catered for children’s books and

picture books. Pino Boero and Carmine De Luca felt obliged to refer in the section of their seminal book

La letteratura per l’infanzia (

Children’s Literature) dedicated to editorial pathways,

I percorsi dell’editoria[

11], to the experience of

Emme as one of the most innovative—and, probably for that reason, the one most open to discussion—at the time, “When the books published by Rosellina Archinto ‘s

Emme Edizioni appeared in the bookshops it is said that someone, looking at the relatively high price tag said, “These are books for the children of Milan’s architects”. The anecdote—even if it untrue—is telling nonetheless, because it brought to the fore the suspicions, the smugness, the irony which surround all attempts at renewal, and which, just to be contrary, take only what exists into consideration: Archinto realised how poor the visual universe intended for children was and therefore decided to produce sophisticated books; because she was aware of the conformism expressed in the texts meant for children back then she decided to produce books that were provokingly civil in content. Through the books issued then by

Emme passed an Italy which sought to look towards Europe and the world. It suffices to flick though fifteen or so books published during the early 1970’s to realise the true value of the proposal” [

11] (pp. 287–288). The two scholars did not fail to mention in a note, the “baby” Italy’s debt to

Emme, “not only for the variety of the choice of product (format, type of illustration, content) but also for the poised, civilised and human lesson conveyed by the catalogue” [

11] (p. 374). This is probably why Paola Pallottino chose to conclude her career as an illustrator for children when the

Emme Edizioni were born [

12].

Emme represented a “watershed”, an experience which, in the words of Antonio Faeti, shattered the barrier of exclusion raised against literature for children then existing in Italy [

13].

The idea of childhood which guided Rosellina Archinto was that of the “competent” child, who from pre-school times on, deserved chances, opportunities and good books. At a time when nobody, as we have tried to emphasise here, spoke of fostering pre-school reading, of

emergent literacy,

Emme’s catalogue offered little readers and their parents books capable of fostering sharreading out loud, but also of acting as a backdrop to early attempts at reading on one’s own [

14] (p. 6).

It was in the 1980’s that the

primilibri (firstbooks) saw the light. These were small

board books, designed by the celebrated English illustrator Helen Oxenbury, and meant to accompany children in their development when they began to take their first steps. “I chose to publish them—Rosellina Archinto told me—because i held and still hold that children are entitled to read—in the sense of touching, looking—, from the very first months of life. By means of books children gradually make sense of the world and build their own stories of it” [

14] (p. 24).

The tiny protagonist, always the same, from story to story, accompanied the reader, small like himself, on a road leading to the discovery of the world.

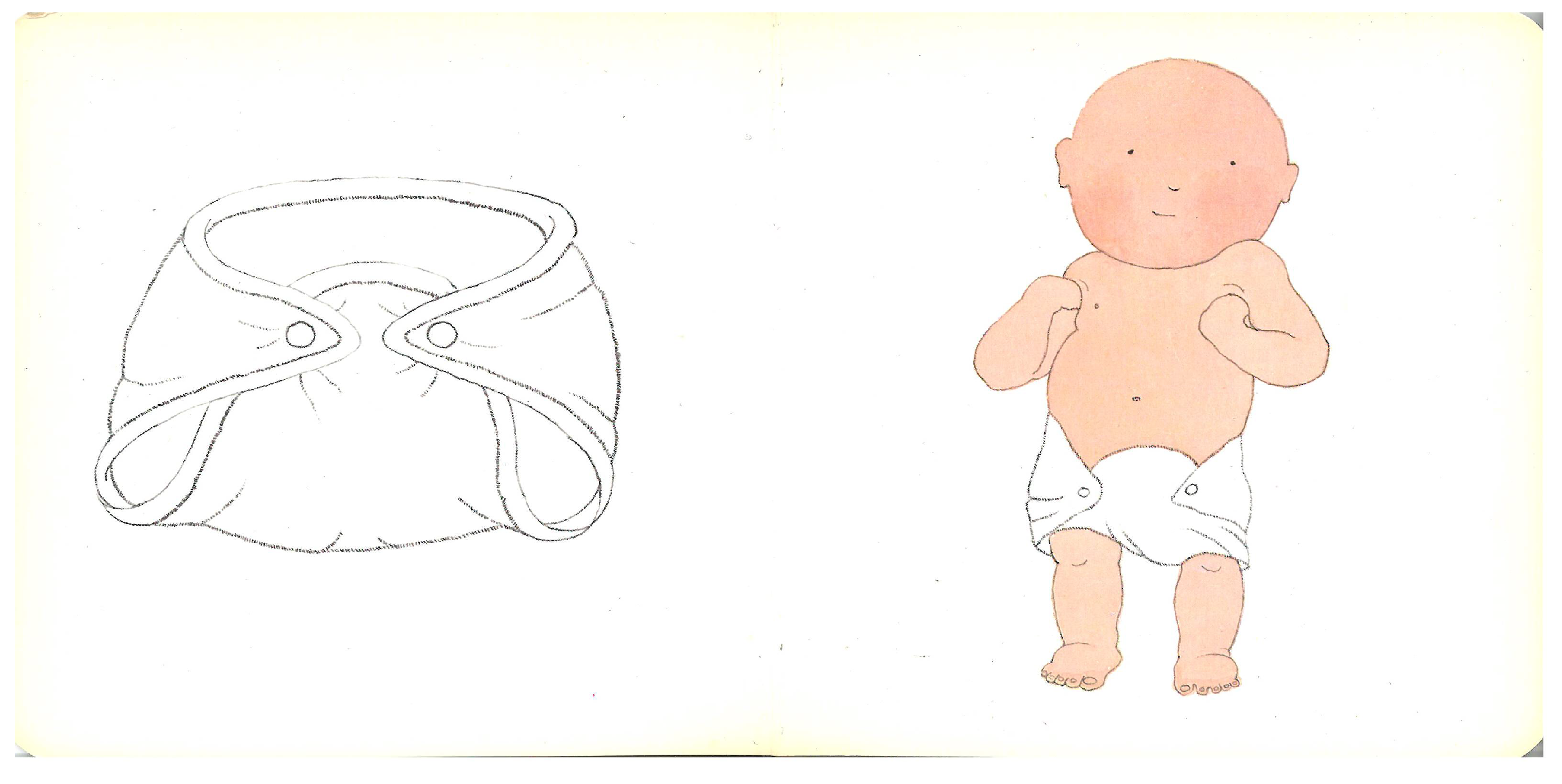

3. “In the Beginning Was a Nappy... the Primilibri Series

The first book of the series came out in 1981. The protagonist, always the same, accompanied the reader, small like himself, from story to story in five booklets, down the road towards the discovery of the world (

Dressing (The original English titles in square brackets.)

I miei vestiti [

15], (

Working)

Il mio lavoro [

16], (

Family)

La mia famiglia [

17], (

Games)

I miei giochi [

18], (

Friends)

I miei amici [

19]. Oxenbury’s work as an author for very small children is closely linked with her own life story, as the wife of an illustrator, John Burningham, “for me it was like attending a course on illustration” [

20], she said in an interview, and a mother of three children, “When we decided to have a family, I did not wish to leave my children because I had to go out to work; I wanted something that would allow me to stay at home, and so I began illustrating children’s books” [

20], she continued. The first were

Counting and

ABC books.

She was expecting her third child when publisher Sebastian Walker, who had just set up a new publishing house, asked her to work on texts for very small children. The times, as she told the publisher the, would be ripe after the birth of this child.

Helen had just begun to set her mind to it, when her youngest child, Emily, came down with infantile eczema, “We were up all night with her and had to invent ways of taking her mind off her illness. By pure chance we began showing her catalogues of objects and clothes for children and realised that she was so taken by them that she forgot to scratch herself”.

The first

board books, published by Sebastian Walker and which illustrated ordinary the everyday routines of babies which Oxenbury, in the same interview, explains as follows, “I believe that

board books need to be extremely simple, as babies’ experiences are closely associated with the things they do, their mother, what they eat, the clothes they wear … the potty on which they sit. They don’t need a text nor do they need to tell a story as such. They are books about “babies and things”.

Dressing, for example, begins with a newborn in a nappy who is then dressed … A

board book acts as a means to help the baby name things and become acquainted with objects she meets every day” [

20].

To make these albums more manageable for very small children, Oxenbury redesigned the layout: a page with words facing another with a big illustration without words or, if there were no words on the first page, two large, logically linked illustrations facing each other. The pages in strong cardboard with rounded corners made board book easy for small hands to manage and stand up to the many “uses” and “abuses” they might undergo.

Of particular interest, to understand this layout, we have the presentation of the book

Dressing—in Italian translated as

I miei vestiti— (

Figure 1), contained in the catalogue printed by Archinto for a recent exhibition dedicated to the publishing house and used to explain all the other little books belonging to the series, “In the beginning was a nappy, which acted as the basic, then came all the rest. The small baby observes the clothes on his right, which are his and which, little by little, he finds he is wearing: a striped jersey, blue knee-socks and red patent shoes. The pages, the size of a CD, the proper size for small hands, continue to turn until the baby is dressed. Then, the baby is ready to go out” [

21].

Figure 1.

An illustration from Dressing, I miei vestiti (My clothes) in Italian.

Figure 1.

An illustration from Dressing, I miei vestiti (My clothes) in Italian.

That child, the same in all the other books in the series, discovers animals (I miei amici) (Friends); playthings including and, not by chance, a book (I miei giocattoli) (Toys); his daily life—his highchair, potty, pram, food, bath, bottle and cot—(Il mio lavoro) (Working); and finally mummy, daddy, sisters, brothers, granddad and granny (La mia famiglia) (Family).

In her albums Oxenbury narrates the true, non-idealised life of real children, committed to coming to terms with reality, with a slight touch of irony, present in every text in nuce, as an instrument of survival indispensable to development.

Every book seeks to encourage the small child, not only as stated, to discover and get to know the world—that closest to him—, by means of play between parent and child, but, when at about the age of 8–9 months he begins to understand that a book is a not a toy like all others, to approach the universe of reading and discover his first real book, with a parent—the parent-child relationship is central for Oxenbury—called upon to read and co-build the narration. According to Oxenbury, this occuts precisely thanks to the presence in the text of easily recognisable elements and the parent-child game of “question and answer” which may amuse the adult too and avoid the boredom often arising from having to read the same pages over and over again, a state of mind capable of undermining the custom of reading out loud [

22].

The five primilibri present, in fact, traits that later become typical of literature for children aged between 6 and 12 months and which may be summed up as follows:

form: “book”, “squarish”, small, with only a few pages in tough cardboard with rounded corners, manageable, washable, a-toxic; readable “using the whole body”;

content: it does not tell a “story” as yet, it simply presents things the child meets in his everyday environment, to help him discover and organise it. If a narrative structure does exist—because there is, for example, a character (an animal or a child, etc.) who presents objects and how to use them– this presence is reduced to essentials and usually aimed, by presenting objects, at telling about small routines the baby can easily recognise. The characters are designed in such a way as to permit spontaneous identification, facilitated by the serial appearance of the same protagonist;

verbal language: when it is present, it is simple, direct, close to the child’s own limited vocabulary. It favours the reconstruction of the narrative thread by following a succession of illustrations with which it integrates;

illustrations: light, fresh, clear, immediately readable, not tridimensional; they reproduce, in a clear manner, easily recognisable objects, often linked thanks to logical (for example, clothes, playthings, animals, etc.) and causal association (on one page, for example there is the picture of an object while on the one facing it, the same object is being used) and portrayed from the child’s perspective. The colours are flat, saturated, bright and decided; the characters and objects are clearly outlined in a dark colour so that they stand out against the white background [

21]. Generally speaking, each page presents very few centred elements (usually, just one), and the protagonist, portrayed also in dynamic situations, is immediately distinguishable from any other element in the picture. The pictures, suited to this age-group, invite the child to recognise the objects, people, animals represented. The warm colours and facial expressions should provide an image at once curious and cheerful, active and far removed, as yet, from the psychological conflict and problematic situations which may be presented at an older age [

23,

24,

25,

26].

This way of conceiving literature for babies arrived in Italy, as we have seen, thanks to the foresight of Rosellina Archinto—it is no coincidence that the

primilibri are listed in the abovementioned catalogue under the heading “scopertinelmondo da Emme” [

21] (discovered in the world by

Emme). Later, several analogous publishing projects catering for the same age-group followed

Emme’s example: one was that by Linne Bie and published by AER, featuring a little girl called Rosalina, aged 18 months, portrayed in everyday situations. Rosalina plays at home, gives a doll its bottle, wheels her pram, plays ball, hugs a teddy bear, reads a book, plays a drum (

Rosalina gioca in casa) [

27] (

Rosalina playing at home). Rosalina plays outside, she sits on soft green grass, she feeds crumbs to some birds, she picks wild flowers, she waters other flowers; she plays with a bucket and spade on the beach, she plays with insects and butterflies (

Rosalina gioca fuori casa) [

28] (

Rosalina plays outside).

Rosalina is a “real” hild, just like the little protagonist of the Oxenbury books, her child’s eyes observe and discover the world presented on paired “dual-text” pages, in strong, resistant cardboard, “squarish” in form. On the left-hand page of the two is drawn, on a plain white surface, the object which creates the situation, on the right-hand page we find the action that regards it. The situation is narrated using simple drawings, having clear outlines and bright colours and two lines of text in words which, while being simple and essential, are also full of sound and rich in sensorial solicitation.

Yet the greatest inheritance that Oxenbury seems to have left to Bie and to the many other authors who have chosen to cater for early childhood, is that “baby worldview”, which, on every couple of double pages, tells about an everyday reality that of any child whatever. Mary M. Burns, in a presentation dedicated to Oxenbury in the

Horn Book, a magazine of children’s literature, reflects on the author’s simple style, so simple as to merit comparison with “the descriptive style used by children”. She writes that Oxenbury “not only knows how children move, but also how they think” [

29] and that she seems capable of revealing to readers what, according to Allison Lurie, was the “big secret” of those who write for children, the secret of remaining “children forever” [

30].

If that were not the case and if the author had forgotten what it meant to be a child, she would probably not have written what she did in the

Junior Book Shelf magazine regarding the intelligence of children: “I believe that children have a good sense of judgment which enables them to understand immediately what adults are saying, writing, or drawing about them, which accounts for the unpopularity of some drawings similar to theirs, which appear in some books (...). Illustrators are wrong if they think children can best recognize themselves in drawings similar to their own, they are probably disappointed that an adult can do no better than them” [

31].

This brings to mind what Rosellina Archinto used to say to those who asked her, with a book of hers in their hands, that “you can’t tell these things to children”: “What do you mean, you can’t? You must! Children need to be told about things as they are!” [

32] (p. 23). Even the things contained in a small “squarish” book before learning to read.

4. From Primilibri to the Osservare Leggere Inventare Anthology; “Building Readers” Inside and Outside of School

This is the kind of attention that Rosellina Archinto transferred from her little picture books to a school anthology called

Osservare leggere inventare [

33] (

Observe read invent).

Was it that the school textbooks in circulation at the time seemed to her to be more harmful than beneficial to child development? Certainly, in the essay

Leggere inutile [

34] (

Useless reading) her criticism of the backwardness of textbooks was ruthless. She had undoubtedly taken stock also of ferment surrounding the debate on school textbooks (associated with Law n. 517, 1977, which authorised the adoption of material other than textbooks) led by the

Movimento di Cooperazione Educativa(

Movement of Educational Cooperation) of which she was a staunch supporter.

The two volumes of this anthology, edited by Gioacchino Maviglia, one for the first, the other for the second year of primary school, a unique experience in the world of publications for Italian schools at the time, contain pages drawn from the illustrated booklets published by Emme and, which tell about the world: nature, fruit, flowers, plants as well as the processes and cycles which regulate their lives; the cyclical alternation of the seasons; animals and how they reproduce; colours; but also stories of childhood, growth and development; the adventure of growing up, and, therefore, themes regarding identity, difference, conflict, integration, and understanding; and again friendship, the family: in a nutshell, the grand themes of life, those usually found in classical anthologies and dealt with in series of teaching units which alternate literary passages and explicative summaries. In these volumes the same topics are addressed using the synthetic code of the picture book, so that they may be understood even by very young children.

In the volume for the first-year elementary class we find Il palloncino rosso (The red balloon) by Iela Mari, La mela e la farfalla(The apple and the butterfly) by Iela and Enzo Mari; Sembra questo sembra quello (It seems to be this, it seems to be that) by Maria Enrica Agostinelli; Il mio cane ed io (My dog and I) by Yutaka Sugita; Era inverno (It was winter) by Aoi Huber; L’uovo e la gallina (The egg and the hen) by Iela and Enzo Mari; Sulla spiaggia ci sono molti sassi (On my beach there are many pebbles) by Leo Lionni; piccolo blu piccolo giallo (Little blue and little yellow) by Leo Lionni; L’albero dei palloni (The football tree) by Donald Windham; La casa più grande del mondo (The biggest house in the world) by Leo Lionni; Un colore tutto mio (A colour of his own) by Leo Lionni; L’albero automobile by Arnaud Laval and Jacqueline Held; Alessandro e il top omeccanico (Alexander and the wind-up mouse) by Leo Lionni.

In the volume for the second class we find L’albero (The tree) by Iela Mari; Se …(If …) by Bob Gill; Il topo dalla coda verde (The mouse with the green tail) by Leo Lionni; Federico (Frederick) by Leo Lionni; Guerra e pasta (War and pasta)by Michael Foreman; Guizzino (Swimmy) by Leo Lionni; Il popolo e i pirati (The people and the pirates) by Alberto Longoni and Mario Soldati; I Su & i Giù (Ups and Downs) by Bob Gill; Orazio (Horace) by Michael Foreman; Celestina by Tullio Ghiandoni and, finally, La scarpa in fondo al prato (The shoe at the bottom of the field) by Nico Orengo and Nicola Bayley.

The write-up on the back cover explains the rationale of the operation carried out by Archinto with Maviglia: “This collection of readings forms a “book-shelf” which provides the children with several motivating books. To include them here only some technical changes have been made but they have not interfered with the original texts or illustrations. These books are not meant just to be read; they may also be looked at, told, interpreted and used to prompt ideas to use for inventing others” [

33].

Between these lines written by the editor, we are actually being told that is possible to have a school without grids and explicatory files, because a textbook made of words and pictures actually contains, as the title tells us, all we need to observe, read and invent. Meanwhile, by means of this offer of “quality” literature, reading at school is fostered too.

The two volumes actually reveal Archinto’s conception of reading as a process to be carried out both within and without the school. It involves dialogical reading in the arms of mummy or daddy, beginning with board books which then moves on to picture books and wordless books though it does not end there—nor ought it—but goes on, ideally, to join the reading experienceled by the primary teacher, amid blackboards, daises and desks, following a “circular route”, an undoubtedly exacting and tiring task, but fundamental if we wish to “create” readers.