A Study of Gender Advertisements. A Statistical Measuring of the Prevalence of Genders’ Patterns in the Images of Print Advertisements †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses

- (1)

- The strongest gender’s stereotypes, identified from Goffman, still survive in the modern advertisements.

- (2)

- Some patterns of gender’s images in print advertisements have changed since Goffman’s study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Survey

- (1)

- the population size: 686 magazines (sold in Italy between November 2015 to January 2006) divided in 7 homogeneous categories (called stratums);

- (2)

- Survey’s technique: a technique of proportionate stratification has been employed;

- (3)

- First stadium of the stratification: random selection (The syntax for the RANDBETWEEN function in Microsoft Excel is: RANDBETWEEN( bottom, top)) of 2 magazines for each category, there were 941 advertisement’s pictures, of which 580 featured human subjects;

- (4)

- Second stadium of the stratification: 100 pictures were randomly selected from the sample of the previous 580 pictures that has been selected in the first stadium;

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Verifying Hypothesis (1)

4.2. Verifying Hypothesis (2)

4.3. Verifying Hypothesis (3)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

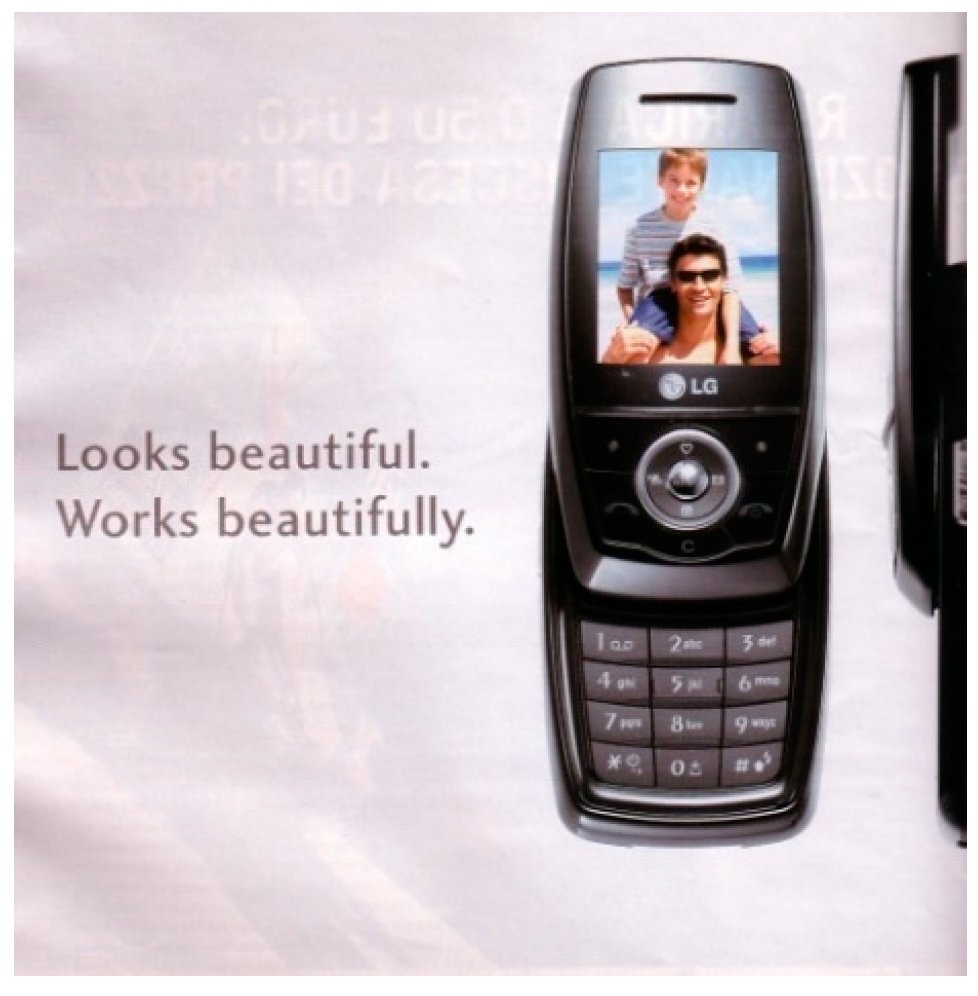

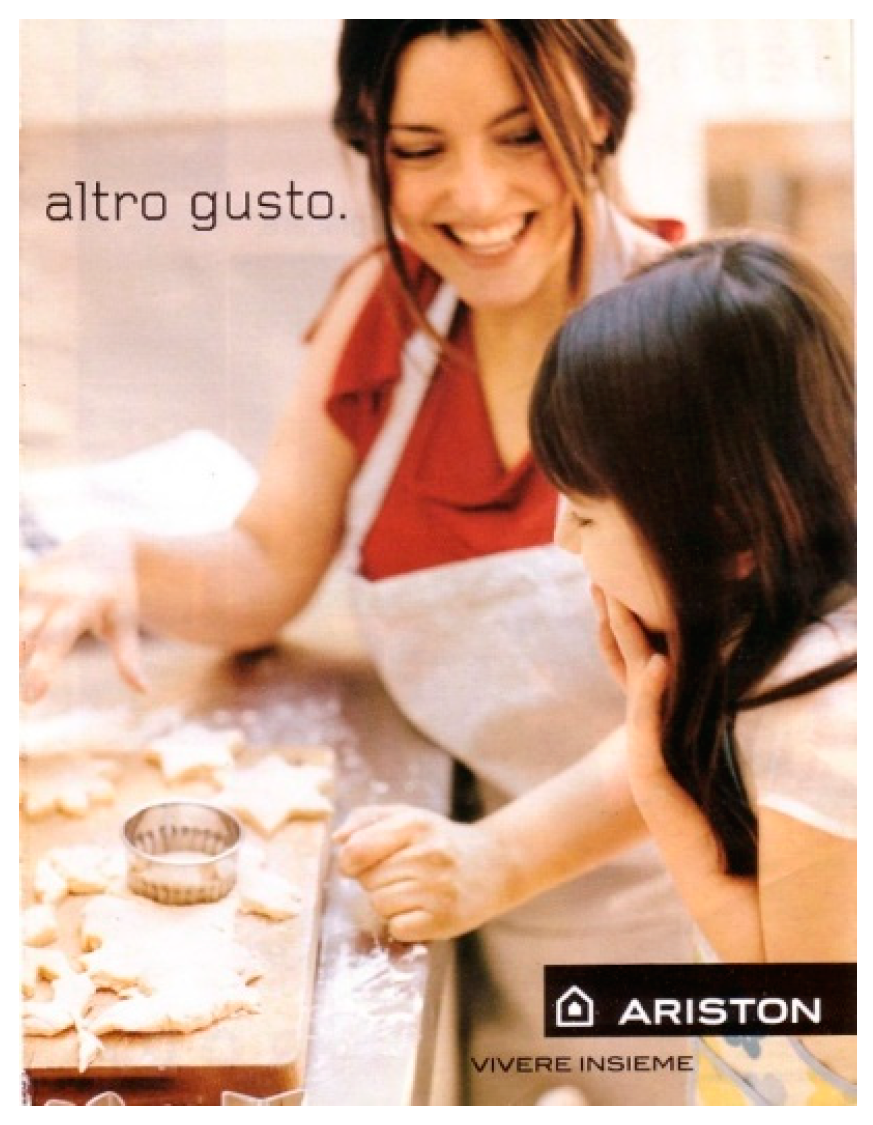

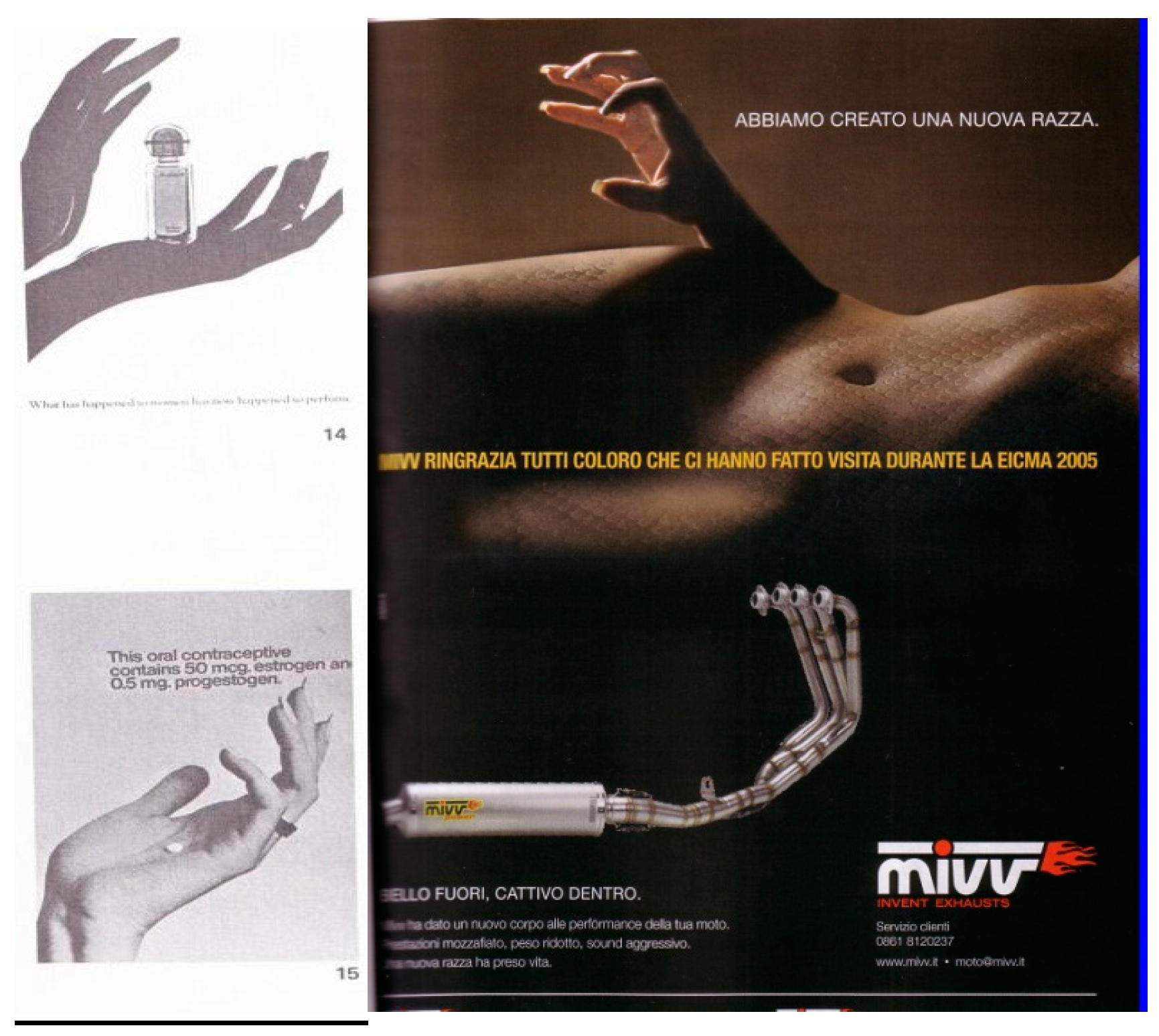

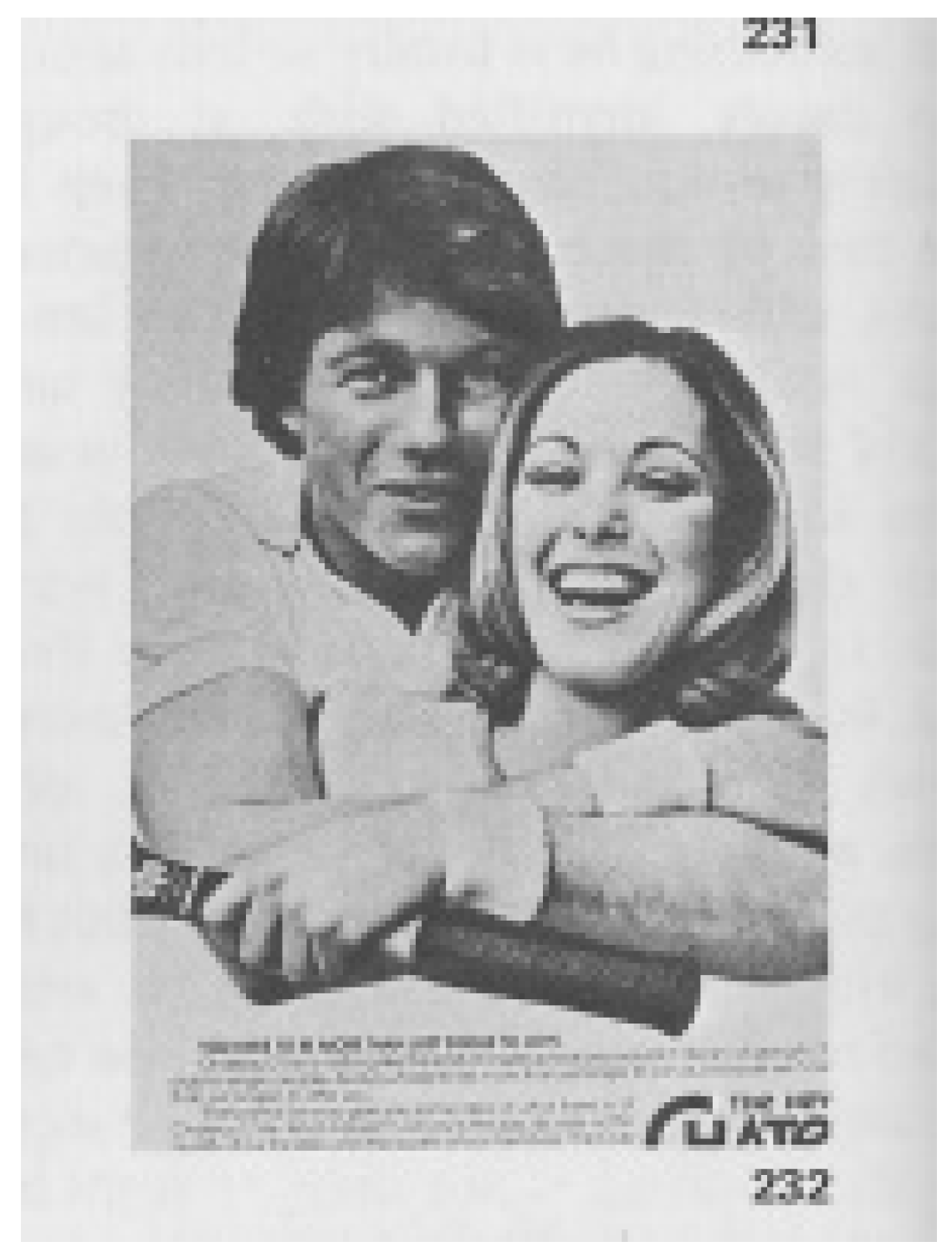

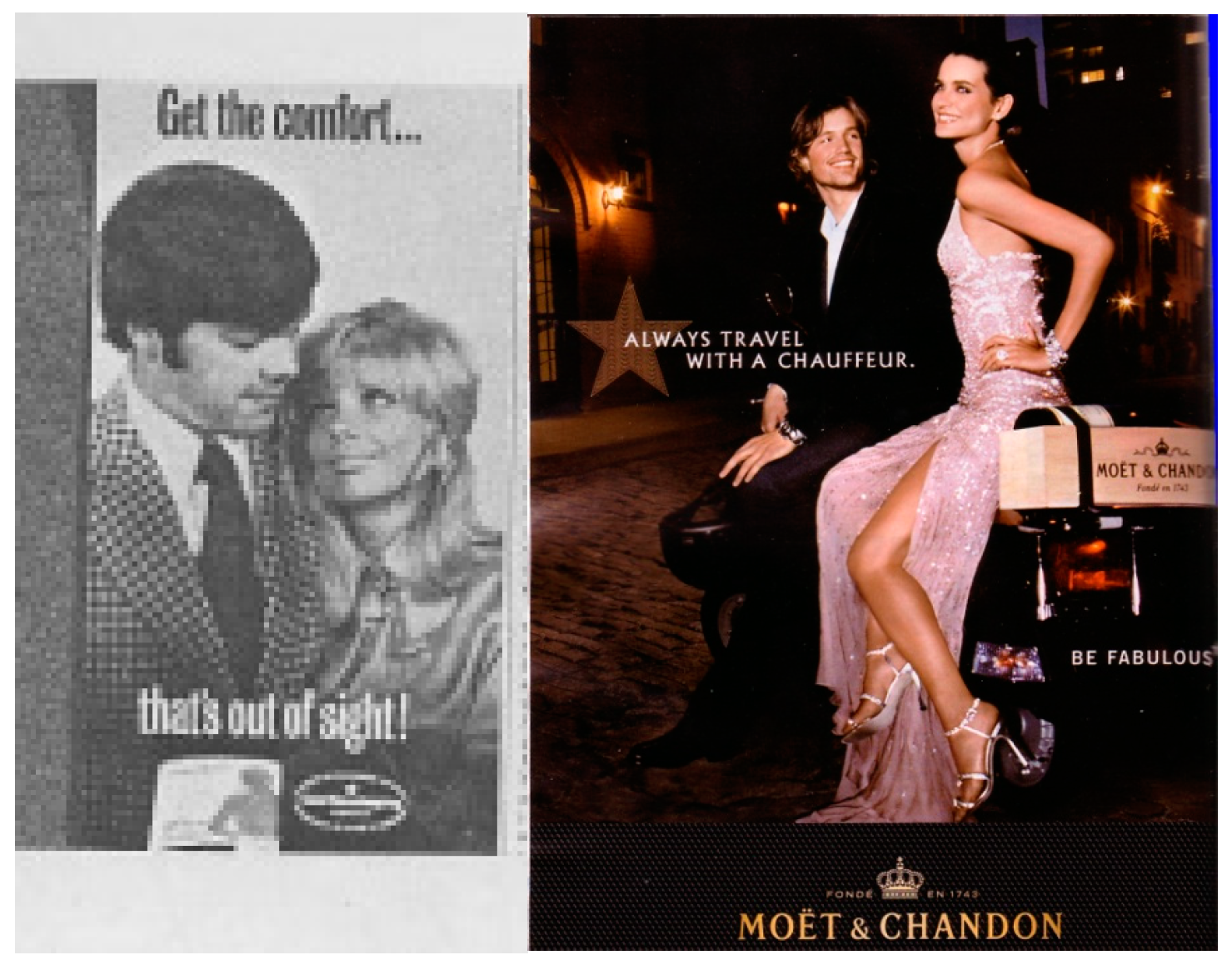

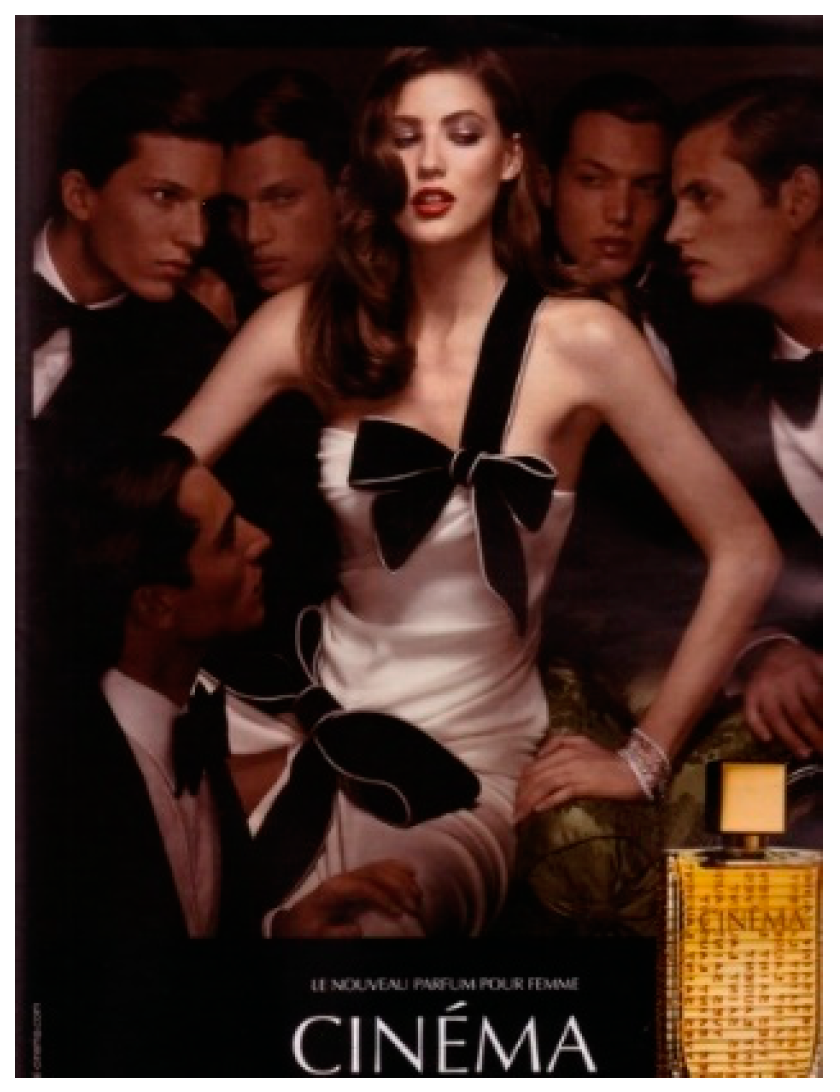

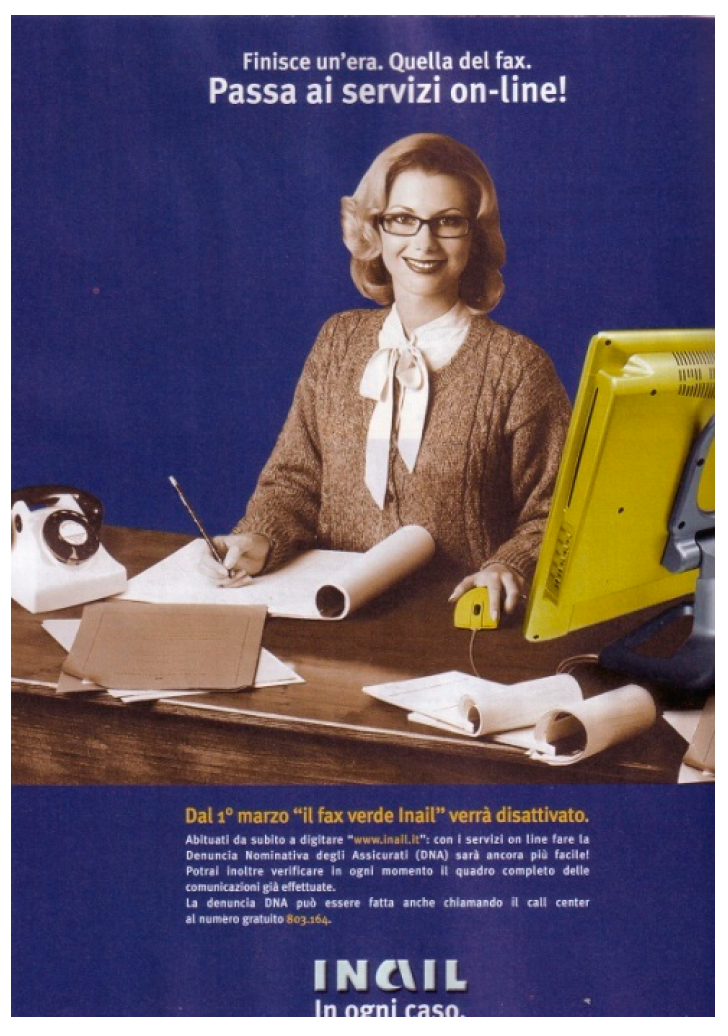

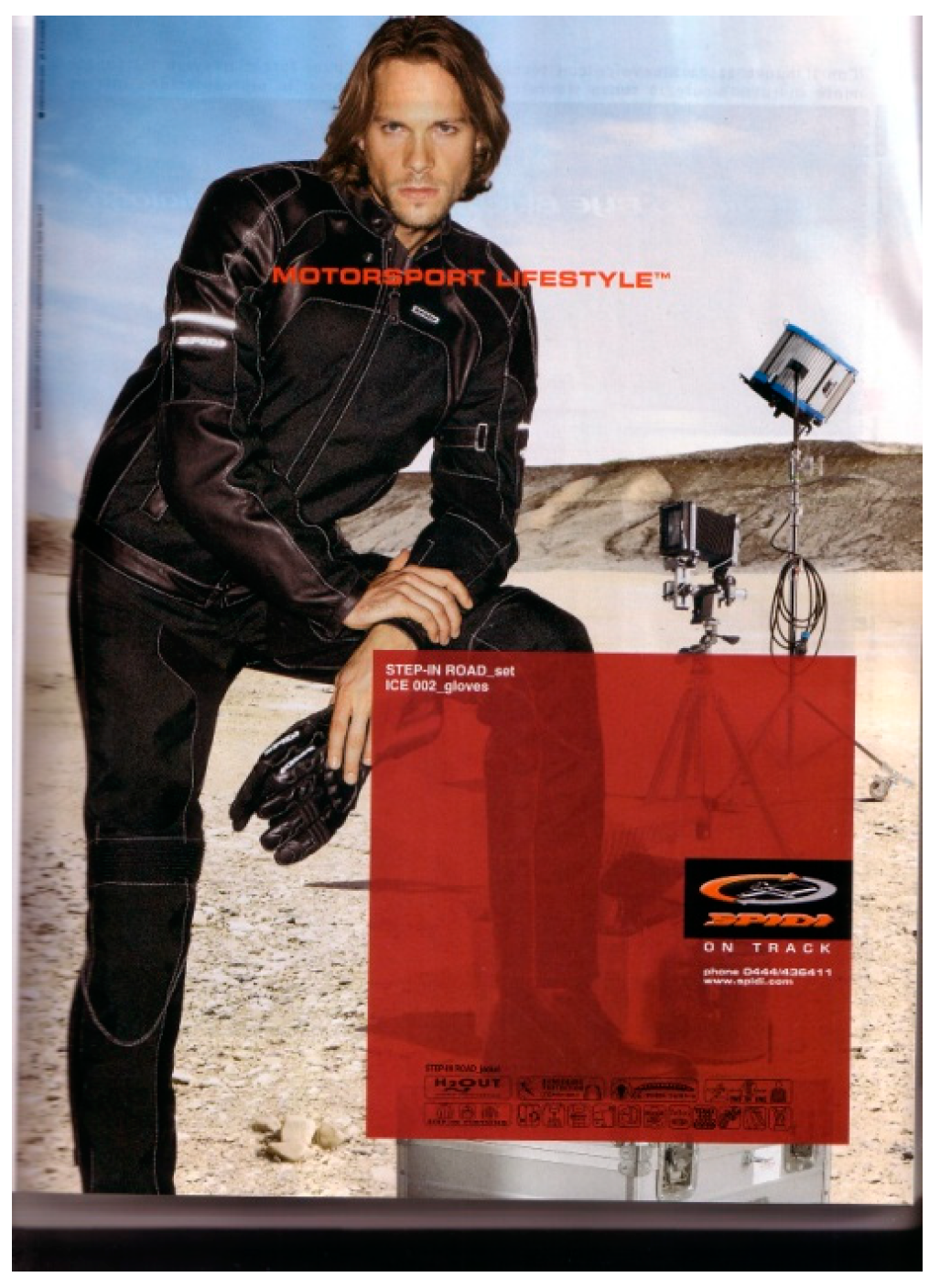

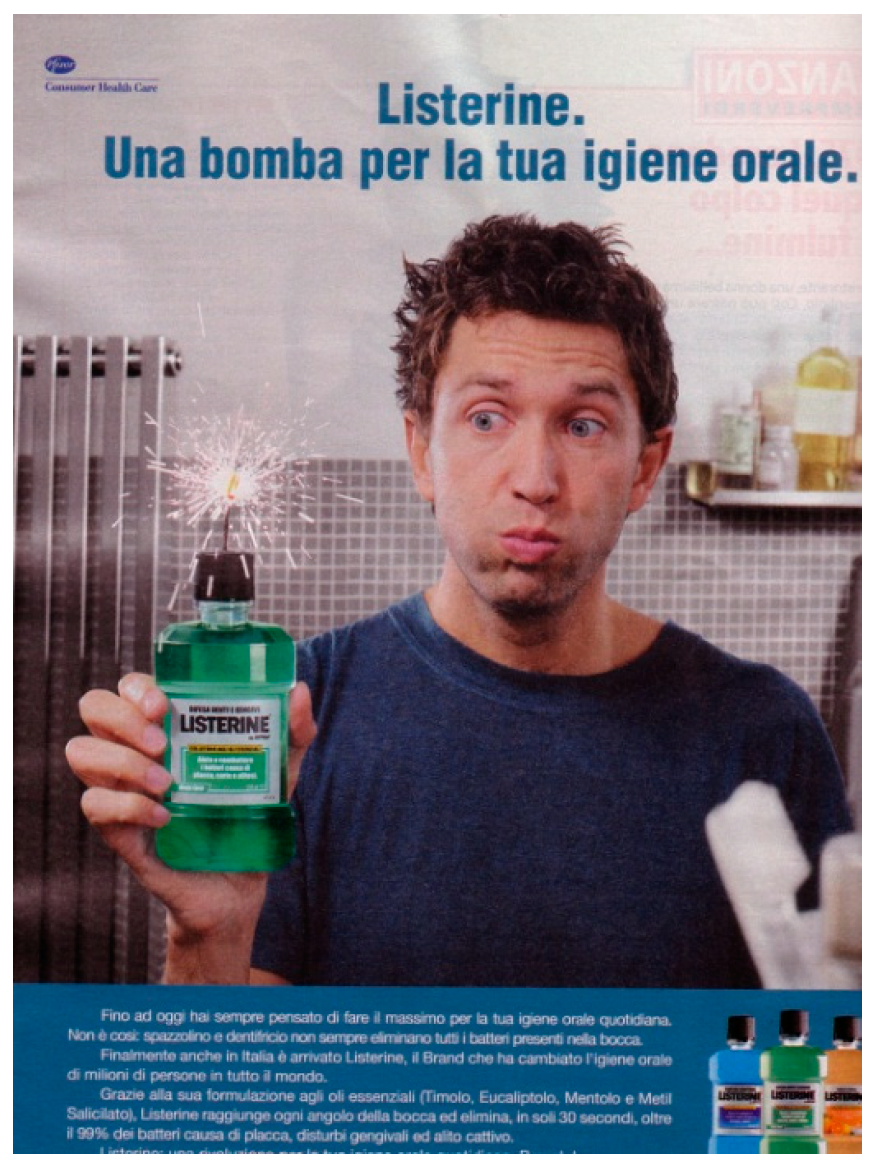

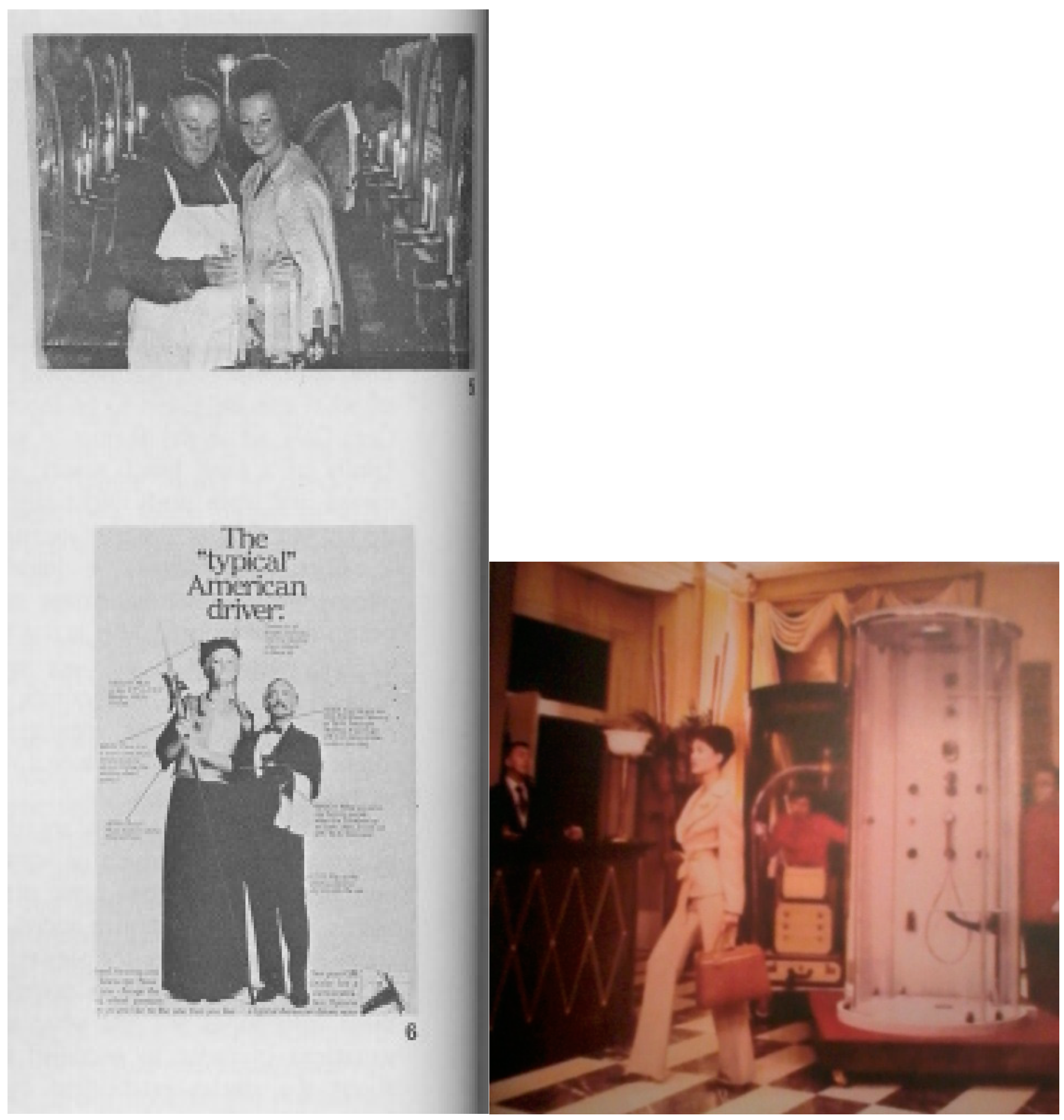

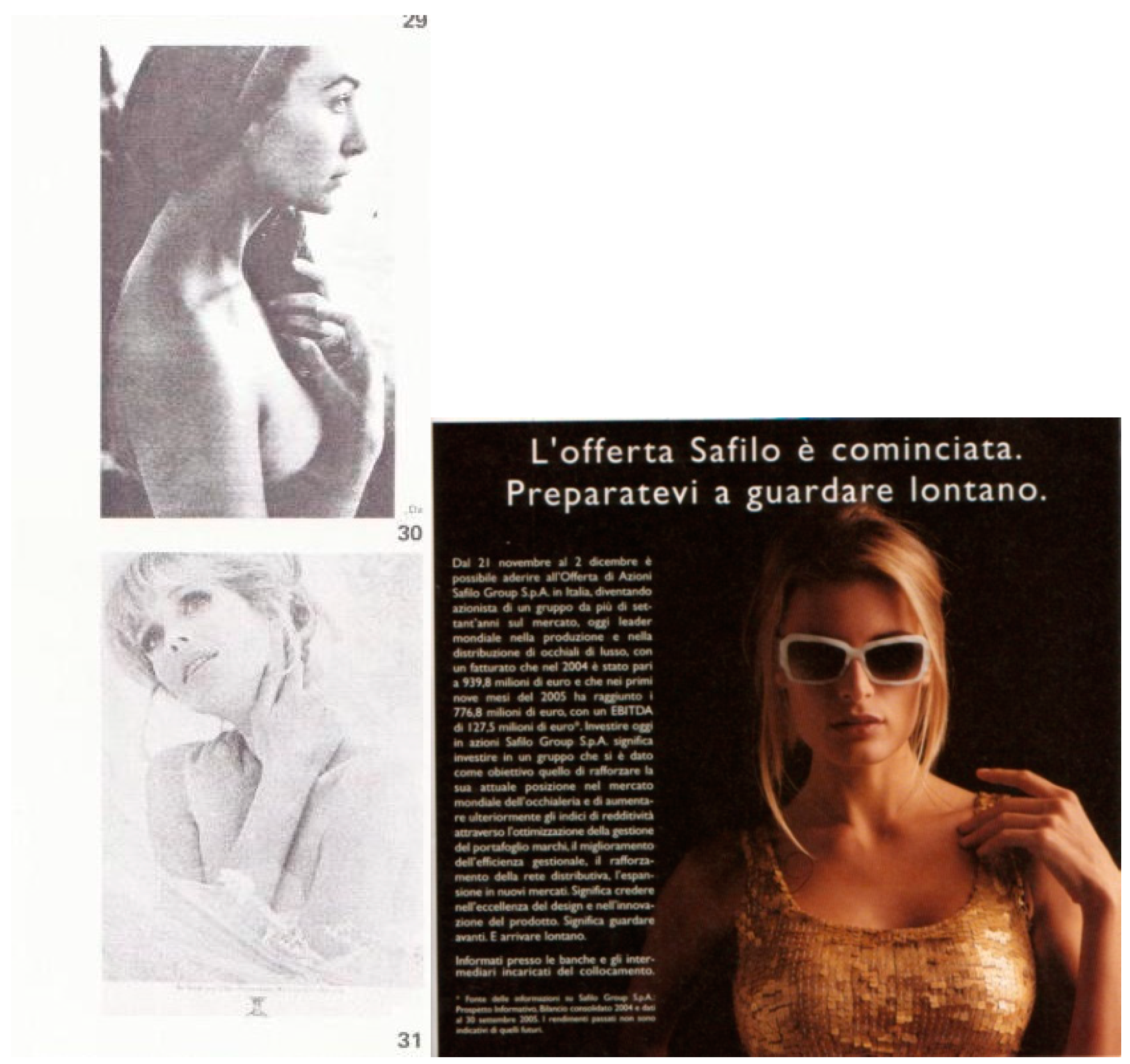

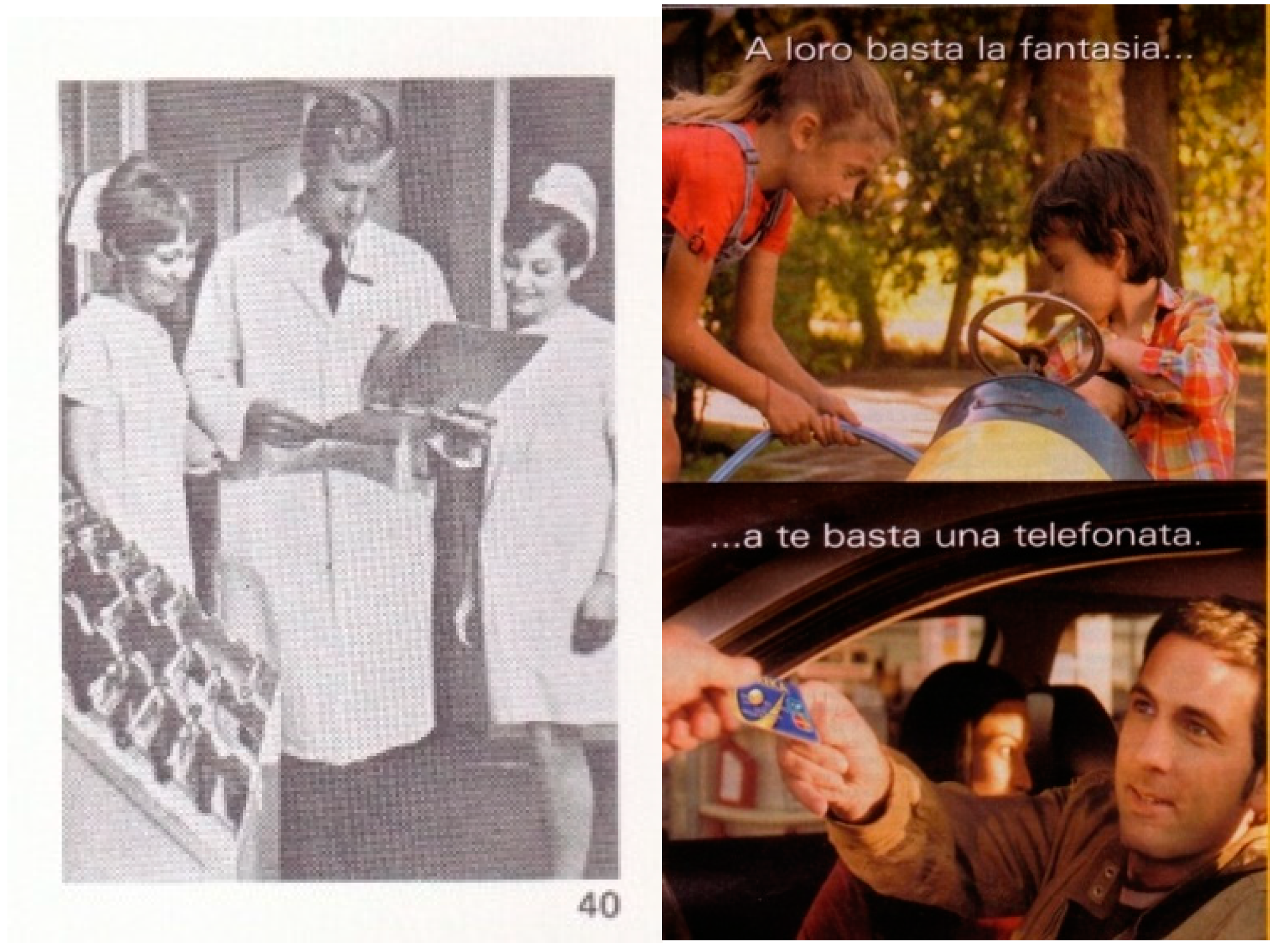

Appendix A (Further images)

References

- Acevedo, C.R.; de Arruda, A.L.; Nohara, J.J. A Content Analysis of the Roles Portrayed by Women in Television Advertisements: 1973–2000. XXIX EnANPAD—Encontro da ANPAD (2005); Published by ANPAD; 2005; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, L.A.; Babbie, E.R. The Basics of Communication Research; Wadsworth: Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Belkaoui, A.; Belkaoui, J. A Comparative Analysis of the Roles Portrayed by Women in Print Advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D. Sexuality and the Mass Media; Siecus Report; 1996; Volume 24, pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, C.W.; Baldwin, C. Gender and class stereotypes: A comparison of U.S. and Taiwanese magazine advertisements. Race Gend. Class 2004, 11, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane, S.; Messineo, M. The perpetuation of subtle prejudice: Race and gender imagery in 1990s television advertising. Sex Roles 2000, 42, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, M. The commercial value of history: A relevance theoretical analysis of historical signs in print advertisements. Lang. Matters 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, A.; Lockeretz, S.W. A woman’s place: An analysis of the roles portrayed by women in magazine advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, K.L. The social-psychology of female male relations—A critical analysis of central concepts. Contemp. Psychol. 1987, 32, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Duker, J.M.; Tucker, L.R., Jr. Women’s lib-ers versus independent women: A study of preferences for women’s roles in advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Faludi, S. Backlash: The Undeclared War against American Women; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunado, J.A. Making Media Content: The Influence of Constituency Groups in Mass Media; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, K.T.; Cheng, H.; Shaw, P. Race and beauty: A comparison of Asian and western models in women’s magazine advertisments. Sex Roles 2004, 50, 5361. [Google Scholar]

- Gauntlett, D. Media, Gender and Identity: An Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Gender Advertisements; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gronhaug, K.; Heide, M. Stereotyping in country advertising: An experimental study. Eur. J. Mark. 1992, 26, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, G.V.; Moreau, P.; Schwarz, N. Gender typed advertisements and impression formation: The role of chronic and temporary accessibility. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-E. The portrayal of women’s images in magazine advertisements: Goffman’s gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles 1997, 37, 979–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, J. Still killing us softly: Advertising and the obsession with thinness. In Feminist Perspectives on Eating Disorders; Fallon, P., Katzman, M.A., Wooley, S.C., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.L.; Ward, L.M. Pleasure reading: Associations between young women’s sexual attitudes and their reading of contemporary women’s magazines. Psychol. Women Q. 2004, 28, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafky, S.; Duffy, M.; Steinmaus, M.; Berkowitz, D. Looking through gendered lenses: Female stereotyping in advertisements and gender role expectations. J. Mass Commun. Q. 1996, 73, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazier-Smith, L. No respect. In Women in Business; United States, 1990; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, K. Images of women in general interest and fashion magazine advertisements from 1955 to 2002. Sex Roles 2004, 51, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, N.J.; Covell, K. The impact of women in advertisements on attitudes toward women. Sex Roles 1997, 36, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarty, C.; Yzerbyt, Y. Vincent & Spears, Russell Stereotypes as Explanations: The Formation of Meaningful Beliefs about Social Groups; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M.E.; Treiber, L.A. Race, Gender, and Status: A Content Analysis of Print Advertisements in Four Popular Magazines. Sociol. Spectr. 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pious, S.; Neptune, D. Racial and gender biases in magazine advertising—A content-analytic study. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 627644. [Google Scholar]

- Posavac, H.D.; Posavac, S.S.; Posavac, E.J. Exposure to media images of female attractiveness and concern with body weight among young women. Sex Roles 1998, 38, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S. Communicating with the Sexes: Male and Female Responses to Print Advertisements. J. Advert. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radach, R.; Lemmer, S.; Vorstius, C.; Heller, D.; Radach, K. Eye Movements in the Processing of Print Advertisements. In The Mind’s Eye: Cognitive and Applied Aspects of Eye Movement Research; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, D.E.; Haberman, P. Women in magazine advertisements. J. Advert. Res. 1974, 14, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ardyth, B.S.; Jan, L.W.; Stephen, L.; George, S. Media Management: A Casebook Approach; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahway, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, T.; Stover, W.J.; Villamor, M. Sell me some prestige: American advertising, gender studies. The portrayal of women in business-related ads. J. Pop. Cult. 1997, 30, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.L.; O’Connor, P.J. Women’s role portrayals in magazine advertising: 1958–1983. Sex Roles 1988, 18, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umiker-Sebeok, J. Power and the construction of gendered spaces. Int. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 6, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Banos, J. A woman’s place: A follow-up analysis of the roles portrayed by women in magazine advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 70, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.C., II; Gutierrez, F.; Chao, L. Racism, Sexism, and the Media: The Rise of Class Communication in Multicultural America; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wolin, L.D. Gender issues in advertising—An oversight synthesis of research: 1970–2002. J. Advert. Res. 2003, 43, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. Cognitive and affective priming effects of the context for print advertisements. J. Advert. 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. The Effects of Contextual Priming in Print Advertisements. J. Consum. Res. 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Signoretti, N. A Study of Gender Advertisements. A Statistical Measuring of the Prevalence of Genders’ Patterns in the Images of Print Advertisements. Proceedings 2017, 1, 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090947

Signoretti N. A Study of Gender Advertisements. A Statistical Measuring of the Prevalence of Genders’ Patterns in the Images of Print Advertisements. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):947. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090947

Chicago/Turabian StyleSignoretti, Nicoletta. 2017. "A Study of Gender Advertisements. A Statistical Measuring of the Prevalence of Genders’ Patterns in the Images of Print Advertisements" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090947

APA StyleSignoretti, N. (2017). A Study of Gender Advertisements. A Statistical Measuring of the Prevalence of Genders’ Patterns in the Images of Print Advertisements. Proceedings, 1(9), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090947