Abstract

The paper discusses the importance and role of visual story telling skills in the field of non-designers education as an effective ideation and expressive medium. It presents the process and results of an experimental design workshop held as a warm up activity inside the Visual Design and Visual Communication and Interface Design classes at University of Milano-Bicocca since 2002. The Exercises de Style written by Queneau are the field of exploration of the intertextual translation from text to graphical representation using principles and rules of the visual language.

1. Introduction

Visual story telling has become one of the most important strategies and tool in the field of communication. In the digital ecosystem and social networks, it is mostly practiced in whom are based on pictures and photos sharing such as Instagram, Pinterest, Tumbler and Flickr’ [1].

In an image’s society, the visual language itself is a transversal competence—a soft skill—required in many professional activities and personal branding construction.

Nevertheless, our educational system provides little space for design, historical and critical approach to a figurative culture. Few people, therefore, can consciously read and decode a graphical artifact or render the structure, and the intended meaning.

There are even less educational curricula—both in the high school and at the university—in which drawing and visual design are learned and applied as a meta-language to produce ideas and to share them, on one hand, and as a design field of communication artifacts production, on the other.

At the opposite, where project culture is the primary focus, drawing is one of the most valuable items taught as an essential basic skill and, at the same time, a pervasive one.

It is the method and the knowledge tool of the existent context. It allows to analyze and understand the issues. Furthermore, it is the language to think and express concepts, able to tell the story of an idea, an intuition or a finding and share them with others.

The shape of representation becomes, therefore, the common cultural, social and inter-subjective field where thinking and to reasoning together.

Anyhow, drawing is widening its presence beyond the traditional areas, and it is becoming a pervasive presence, both as a way to self-expression such as the doodling phenomena [2] or as a cognitive resource as in the case of sketch-noting [3], visual thinking [4,5] or visual facilitation [6,7]. Also is nature is evolving along the many fields in which it is involved and practiced.

Visual practitioners are bringing drawing language back: from the taught, standardized, technical and coded rules to its spontaneous, original form, sometimes naïf, but very personal and powerful. It gives people an informal and accessible tool that uses few vocabulary of the visual grammar and syntax: basic shapes, written labels, and an overall organized spatial composition.

Even with a few elements drawing improve understanding, memory, learning, knowledge transfer, and communication management in complex context.

2. Digital vs. Analog

The digital revolution has deeply changed the way we design and produce visual communication artifacts. Almost all the images that we take nowadays, both professional and amateur, are already in a digital format. These pics can be photographs made with a smartphone, a tablet or a digital photo camera or illustrations, layout, info-graphics, and data visualizations directly developed thank to software, algorithms and so on. The mobile frontier has further pushed forward the practical and conceptual boundaries of the field. From the photo editing or vector drawing software, often used with a graphics tablet, the new apps allow to draw with the finger tip on the device display directly generating a new imperfection iconography. The image is created with the more advanced technologies, but it turns back to a sort of primitive analogical stroke. It origins from our hand gesture, with no intermediation between the thought and the act—not even a pencil—between eidos and eidon, between Forstellun and Darstellung [8,9]. As stated by Giovanni Anceschi, describing the inner concept of ostensive manipulation as foster by the introduction of information technology in the 80’s: “È solamente con la raggiunta e fattuale scrivibilità delle figure, prodotta dall’informatizzazione dell’immagine e non più solo nella possibilità di scriverne le formule nel linguaggio del formalismo logico matematico, delle topologie, delle geometrie, delle simmetrie, delle cinetiche, dei modellli catastrofici e degli algoritmi frattali, nonché delle teorie proiettive, delle teorie prospettiche, delle teorie delle ombre, delle teorie dei colori, etc. ma nella effettiva esecuzione calligrafica della tecnologia in azione, nella resa ultima percettiva, è insomma solo con l’aggregarsi di questo insieme di fattori che una unificazione si è fatta oltre che pensabile praticabile” (“It is only when pictures become fully and factually editable thank to the image’s digitization and not more solely in the formalism of the mathematical logic, of typologies, of geometries of symmetries, of kinetic, of catastrophe models and fractal algorithms, of projective geometry, of perspective and shades’ theories, of color theory, etc., but in the calligraphic execution of acting technology, in the definitive perceptive act, it is, in the end, when all these factors merge that a unified whole is not only thinkable but also attemptable.” Translated with author’s supervision) [10].

The dichotomy between thought and images is the basis of the expressive incompetence of whom have been educated to the logical thinking and raised in the humanistic culture in which words prevail on images, text over the drawing as states by Carlini [11]. People have been expropriated of a language practiced in childhood, then abandoned according to a learning system that pushes in the background this kind of skills, settling them exclusively as innate and not learned or trained personal talent.

3. Non-Designers’ Visual Design Classes: A Case Study

Although Communication Science has become one of the most common degrees in many universities, the visual competencies are even not considered and missing despite the broad meaning of communication and the many disciplines involved [12,13,14].

The experimental and practical experience made inside the L20-Communication Science master/degrees at the State University of Milano-Bicocca is a paradigmatic case study [15,16].

The Department of Psychology offers the first level, three years degree in Psychosocial Communication Science (SPC) and a master one, Theory and Technology of Communication (TTC) in partnership with the DiSCO-Computer Science Department (see Figure 1: the 2006 final project design exhibition held in AIAP—Italian Association of visual design—headquarter).

Figure 1.

Images of the exhibition: “Percorsi Visivi” held in 2006 at the headquarters of AIAP Italian Association of Visual Design: visual style exercises workshop results 2002–2006.

Inside the two courses, there is a relatively different offer in the field of visual representation, graphic, and user interface design: Visual Design; Computer science and graphic design for the web at SPC and Visual Communication Lab; Visual Communication and Interface Design at TTC. In the three classes devoted to Visual Design since 2004, a workshop has been proposed with the “Exercices de style” written by Raymond Queneau in 1947 [17] as a project subject. The exercise aims to translate in an intertextual way a written-narrative text in a visual story telling.

The proposed activity has the scope to teach non-designers’ student [18,19] the basics of the graphical language and the verbal-visual rhetoric according to the meaningful learning method developed by Ausubel [20] base on a learning-by-doing [21] proposal.

3.1. Variation as an Expressive Research

Firstly published in 1947 in France, the book has been translated in Italian both by Italo Calvino and then by Umberto Eco, as proof of the extreme linguistic and semiotic interest and value of the text. Einaudi edited again this second version with an afterword by Stefano Bartezzaghi.

The main event of the first basic story is an ordinary episode in a normal day, traffic, public transport, common happenings, divided into three scenes. The first and the second take place in the same space/time continuum, the third, in a postponed time and another environment: the Saint Lazare station in Paris.

The trivial plot becomes the basis on which to “interweave” 99 rhetorical, linguistic, syntactic and perceptual versions.

Besides classical figure of speech—such as metaphors, synecdoche, hyperbole—there are exercises based on the idiomatic aspects—Anglicismes, Italianismes—to the extreme deconstruction of the syntax of the Parts of the Speech.

The exercises’ variations are played both on the formal style and on perspective changes or the ambiguity between the narrator point of view, the protagonist, and anti-protagonist: it’s the case of Blurb (see Figure 2), Reported Speech or Another Subjectivity. Queneau thrives on the edge of pure visible or synesthetic in which words are just an interface to create mood, sounds, emotions, or sensations, i.e., Onomatopeia, The rainbow, Interjections.

Figure 2.

Exercises in Style, texticule: Blurb, developed in the Visual Design class 2016–2017 by Edoardo Bassetto.

As in the Goldberg variations, the inspiration is also found in music, as Queneau states in introducing the French edition in 1963: “during the 1930s, we (myself and Michel Leiris) listened to the Art of Escape together at a concert scheduled at Pleyel Hall. I remember the passion with which we followed and that, when we came out, we said it would be very interesting to do something like that on the literary level (considering Bach’s work not so much from the point of view of counterpoint and escape as well as building of a work by variations that proliferate almost infinitely around a scarce subject). I wrote Exercises in style, realizing myself, and quite consciously, of Bach and especially of that execution at the Pleyel Hall” [17].

Variations become, therefore a way to experiment the range and the expressive potentiality of a language as in the representative and figurative one.

Repetition, reshaping and reconfiguration of classical iconography in different historical time or the obsession of an author for the same subject along his/her artistical life such as the Pity in the case of Michelangelo (from the Pietà Vaticana, over the Pietà Bandini until the unfinished Pietà Rondanini) or the Rubens’ self-portrait to witness the evolution of his pictorial poetry.

Until serialization, mediated by the photos and their reproducibility, investigated by the pop art in which, the cultural debate shifts from the aesthetic evolution to the semiotic and conceptual will and acting of the author.

3.2. Practicing Intertextuality

The translation of the Queneau book brought considerable effort. The work made by Eco is a balance exercise between the original form and preserve the original linguistic and narrative meaning of every single texticules. He declared: “In breve nessun esercizio di questo libro è puramente linguistico, e nessuno è del tutto estraneo alla lingua. In quanto non è solo linguistico, ciascuno è legato all’intertestualità e alla storia. In quanto legato a una lingua è tributario del genio della lingua francese. In entrambi i casi bisogna, più che tradurre, ricreare in un’altra lingua ed in riferimento ad altri testi, a un’altra società, e un altro tempo storico” (“None of these book’s exercises are merely linguistic, and no one is outside the language. Due to its nonlinguistic side, every [texticules] is connected to intertextuality and with the plot. Due to its language connection, it owes to the French language genius. In both cases, rather than translate, it is crucial to recreating it in another language referring to different texts, to a diverse society, to another historical context”.).

It’s not a literal translation, but almost a rewrite which brings into play both his novelist ability and his sensibility as an interpreter as well.

Eco sew the original text and the Italian version throughout an intertextual connection: he transposes from one system of signs—French, in the specific case—to another “accompagnata da una nuova articolazione della posizione enunciativa e denotativa” [22] according to the conceptualization proposed by Julia Kristeva [23]. The author introduces the idea in the artistic field and movie critic according to a semiotic perspective of meaningful practices or meaningful differentiated systems.

It’s important to underline that it is even most true, when moving from a communication channel to another, from a shared sign system to another one, as in the case of visual and verbal language. The risk is a redundancy of symbols and signifiers in the attempt to realize an exact transposition between the two expressive registers. According to Kristeva, this translation should be supported by a new articulation of the enunciative and denotative position.

Every communication channel is characterized by a specific lexicon, by a proper representation form, that can not simply be transposed—with a pure translation—from a modality into another one [24]. The further articulation of the message is a linguistic act coherent with the whole meaning and its particular syntax.

Thus, this activity implies the knowledge both of visual semiotic [25] and visual rhetoric [26] that, generally speaking, are not part of the cultural background the majority of university students.

3.3. Visual Rhetoric Exercises

Practicing a visual interpretation of the Exercises is a way to apply the intertextual approach to let the two signs systems interact: on the one hand the verbal-notation of writing, on the opposite, the graphical one. Therefore, students are asked to use elements of the visual language—colors, shapes, space, rhythm, contrast, and so on—to translate a single texticules preserving the mood. The aim of the workshop is to sharpen the visual rhetoric—or, better to say, visual-verbal rhetoric, according to Anceschi [27]—expressive repertoire.

Drawing, natural expressive channel during the childhood, seems now to be a definite limitation in succeeding. One one hand students must explore visual representation as a language with its own rules again. On the other, they must discover the semiotic processes in images building: the significant attribution and the dynamic activity of meaning attribution.

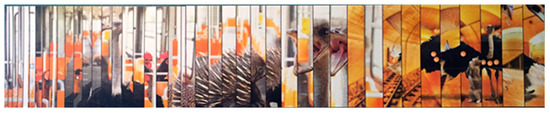

Students are therefore invited to translate the story into the visual-graphic language without the help of the computer or other digital instruments so that the digital inexperience is not a design bias influencing or limiting the final output. Free-hand drawing (see Figure 2, Figure 4 and Figure 5), pictures collage (see Figure 4 and Figure 6), photo composition, mixed or tridimensional materials (see Figure 3 and Figure 6), sometimes fabric are the techniques adopted to express themselves. Words are banned unless they are the graphic elements of the composition. The scope, indeed, is to let them focus on the core of the style both as a story and an expressive style when it comes to adopting the visual language.

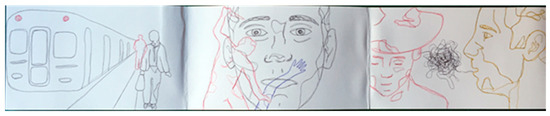

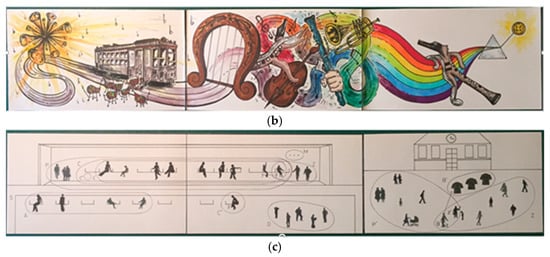

Figure 4.

Exercises in Style, texticule: (a) Abusive, (b) Auditory, (c) Mathematical developed in the Visual Design class 2016–2017 by student Katarzyna Szolcznska, Roberta Mazzaferro and Serena Borgonovo.

Figure 5.

Exercises in Style, texticule: The Subjective Side developed in the Visual Design class 2016–2017 by student Guglielmo Monnecchi.

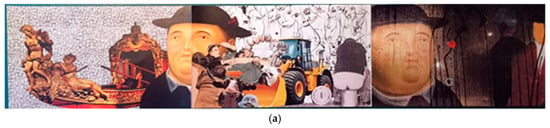

Figure 6.

Exercises in Style, texticule: (a) Parachesis, (b) Permutations by Groups of 5, 6, 7, and 8 letters developed in the Visual Design class 2016–2017 by student Serena Rossetti and Anna Chelini.

Figure 3.

Exercises in Style, texticule: Permutations by Groups of 2, 3, 4, and 5 letters, developed in the Visual Design class 2016–2017 by student Sara Besia.

After ten years of workshop activities, the collected materials are now under revision to be classified, analyzed and clustered to be compared and discussed to find recurrent patterns and representation strategies.

Although this mapping and interpretative phase is still ongoing, some evidence is already emerging. The visual artifacts have been evaluated and organized according to 3 different criteria: (1) the ability to translate the story sequence and mainly actions; (2) capacity to transpose in the visual language the narrative, semiotic and rhetoric construction of the assigned texticule; (3) the ability to use visual language and graphical techniques to express the meaning and the style graphically.

Starting from the lower level, we can identify some recurring approaches:

- Orror vacui: people try to draw in a temporal sequence all the elements verbally described in the text, with many unnecessary and confusing details. The strips are visually dense, blurred, didactic and fragmented. The most common technique is pencil and colored pastels. Visualization is weak in both stroke and contrast (see Figure 5).

- Näif: the student can catch the subject and the overall style but stereotypic in the visual representation. He/she takes the verbal form and symmetrically translate it in the corresponding figure. If the style is Auditory, it is always interpreted drawing a five-line staff, the same for Rainbow or Zoological, the texticules with a lower level of abstraction (see Figure 4).

- Average: style, mood and the temporal development of the story are well understand and visual expressed. Collage of magazines pictures or photo are the common elements used to render in a synesthetic way the style concept (see Figure 5).

It is interesting to notice that at a lower level drawing is used as a spontaneous way to graphically represent the story. The representation tends to be more realistic and simulative of a concrete world. On the other hand, as much as the level of abstraction and conceptualization rise, also the expressive techniques become more articulated, complex and mixed.

It seems that free-hand drawing is the more easy way to represent the plot in a visual dimension, but, at the same time not able to give a full expression. Perhaps in a technological culture, the finished and perfect outlook of a Photoshop layout or a retouched and filtered digital photographs are the are the term of comparison, and they have produced over time a sort of artificial iconography of perfection. On the other hand, students feel themselves not confident in drawing, considering it more as a natural attitude rather than a learned and practiced ability.

The role of drawing and other representation technique is an issue to be further investigated. So it is the previous knowledge of visual language rules borrowed both from the rhetoric culture and from art history.

4. Conclusions

Among many another approaches to teaching the basic elements of representation and the visual language, these workshops give students the opportunity to move from a well-known context, a text, to explore a new field of expression. The bottom up method and the peer and expert review are a way to discover perspectives, meanings and formal aspects of graphic expression.

The activities involve both practical problems, such as the representation tools and techniques, and the conceptual ones. The format constraints become, therefore, a suggestion and a challenge to understand, translate and reproduce using another communication register ideas, emotions, and aesthetical aspects according to the given style.

In the and, students acquire greater awareness and control of communication channels that will bee deepened, together with the use of professional software to achieve a complete mastery of visual language.

Acknowledgments

The workshops are part of the design activities of the Visual Design, and Visual Communication and Interface Design classes at the University of Milano-Bicocca.

Author Contributions

Letizia Bollini has developed, conducted the experimental workshop and she wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bollini, L. Large, Small, Medium. Progettare la Comunicazione NELL’ECOSISTEMA Digitale; Maggioli Editore: Rimini, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-916-1832-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. The Doodle Revolution: Unlock the Power to Think Differently; Portfolio Penguin: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, M. The Sketchnote Handbook: The Illustrated Guide to Visual Note Taking; Peachpit Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 0321857895. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, E. Graphic Design Thinking; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN-10 1568989792. [Google Scholar]

- Roam, D. The Back of the Napkin: Solving Problems and Selling Ideas With Picture; Portfolio Penguin: London, UK, 2013; ISBN-10 0241004373. [Google Scholar]

- Agerbeck, R. The Graphic Facilitator’s Guide: How to Use Your Listening, Thinking and Drawing Skills to Make Meaning; loosetooth.com Library, 2012; ISBN-10 0615591876. [Google Scholar]

- Agerbeck, B.; Bird, K.; Bradd, S.; Shepherd, J. Drawn Together through Visual Practice; Kelvy Bird, 2016; ISBN-10 0692726004. [Google Scholar]

- Anceschi, G; Marini, D. Manifesto eidomatico (e qualche esempio). W.W.N 1987, 7, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Multimodalità vs. Multimedialità. Il Verri 2001, 16, 144–148, ISSN 0506-7715. [Google Scholar]

- Anceschi, G. Scena eidomatica e Basic Design. Il campo unificato della presentazione visiva. Quaderni di Disegno Come Scrittura/Lettura 1989, 8, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carlini, F. Lo Stile del Web. Parole e Immagini Nella Comunicazione di Rete; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1999; ISBN 9788806145736. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Comunicazioni visive una questione di definizione. Progetto Grafico 1998, 3, 20–21, ISSN 0024-3744. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Comunicare la didattica. In Piccoli Frammenti di Città per Abitare; Borsotti, M., Ed.; CLUP: Milano, Italy, 2004; pp. 231–242. ISBN 88-7090-633-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L.; Greco, M. Organizzare Presentazioni Efficaci; Hoepli: Milano, Italy, 2008; ISBN 9788820336899. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Mapping the teaching challenges of User Experience and Interface Design in public Italian University master and undergraduate degrees. In Proceedings of the INTED 2016 Conference, Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2016; pp. 7828–7833, ISBN 978-84-608-5617-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Teaching Visual and User Interface Design in ITC Field. A Critical Review of (digital) Design Manuals. In Proceedings of INTED 2016 Conference, Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2016; pp. 3356–3364, ISBN 978-84-608-5617-7. [Google Scholar]

- Queneau, R. Esercizi di Stile; Giulio Einaudi Editore: Torino, Italy, 1983; ASIN B00QU0CVQU; Available online: http://www.einaudi.it/libri/libro/raymond-queneau/esercizi-di-stile/978880617864 (accessed on 11 September 2017).

- Bollini, L. Il disegno come linguaggio. Esperienze didattiche di comunicazione visiva in contesti non progettuali/Drawing as a language. Teaching experiences in visual communication design for non-designers. In Territori e Frontiere Della Rappresentazione/Territories and Frontiers of Representation; Di Luggo, A., Giordano, P., Eds.; Gangemi Editore: Roma, Italy, 2017; pp. 1203–1210. ISBN 978-88-492-3507-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Visual design for non-designers. A participatory experience based on web 2.0 tools in a multidisciplinary master degree programme. In Proceedings of INTED 2016 Conference, Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2016; Chova, L.G., Martinez, A.L., Torres, I.C., Eds.; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 3157–3162, ISBN 978-84-615-5563-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D.P. Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View; Holt, Rinehart, and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968; ASIN B01K3RT7DA. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Learning by doing: A user centered approach to signage design. Milano bicocca a case study. In Proceedings EDULearn 2010 Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 5–7 July 2010; Chova, L.G., Belenguer, D.M., Torres, I.C., Eds.; IATED: Barecelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 3090–3097. ISBN 978-84-613-5538-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. Registica Multimodale. Il Design dei New Media; Maggioli Editore: Rimini, Italia, 2004; ISBN 88-7090-783-. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeva, J. La Rivoluzione del Linguaggio Poetico. L’avanguardia Nell’ultimo Scorcio del XIX Secolo: Lautréamont e Mallarmé; Venezia: Marsilio, Italy, 1974; ISBN-10 8831751301. [Google Scholar]

- Bollini, L. MUI: Design of the HC Interfaces as a directing of communications modes targeted on human senses. In Senses and Sensibility in Technology; Callaos, M., Ed.; IADE: Lisbon, Portugal, 2003; pp. 182–186. ISBN 972-98701-1-X. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, J. Semioloie graphique; Editions Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1967; ISBN-10 2713224179. [Google Scholar]

- Polidoro, P. Cos’è la Semiotica Visiva; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2008; ISBN 8843045792. [Google Scholar]

- Anceschi, G. Retorica verbo-figurale e registica visiva. In Le Ragioni Della Retorica; Eco, U., e Fenocchio, G., Eds.; Mucchi Editore: Modena, Italy, 1986; ISBN 978-88-7000-102-0. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).