Using Photos in Pedagogical and Intercultural Research with Children. Images and Research: Between Sense and Reality †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. “Images-Talk”: Who’s Really Talking? The Multi-Inter-Dialogue between Images, Researcher and Participants

- Who chooses the photographs?

- Who is the photographer?

- What is represented on the photographs?

3. Children-Photopgraphs-Researcher’s Relations in Qualitative Research

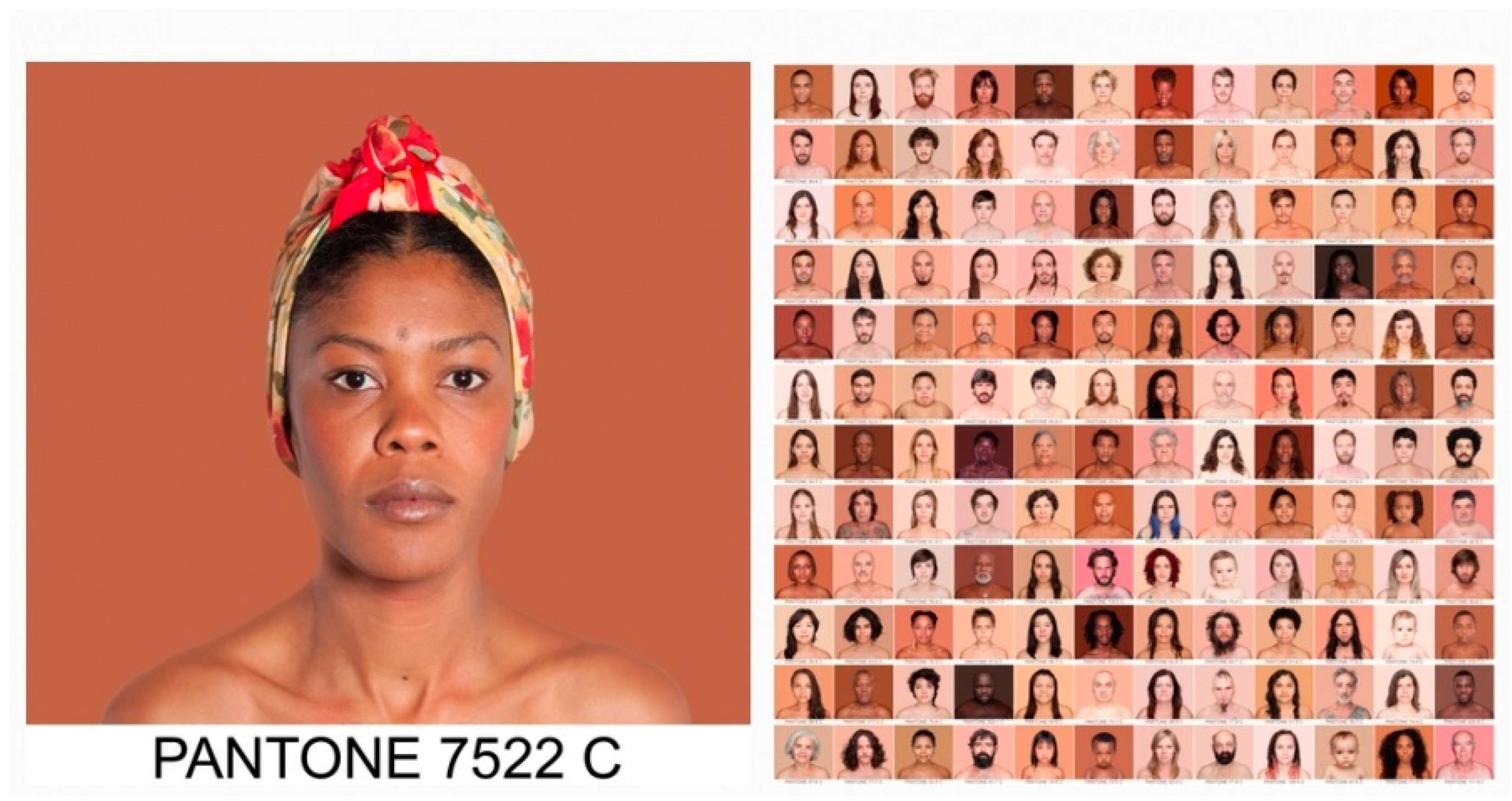

The Photographs’ Choice: Why That One?

- Similar PANTONE gradation (Even if the skin color of the dark skinned people is more similar than the skin color of the light skinned people.);

- No particular “interfering” physical characteristics (i.e., earrings, piercings, tattoos, make-up, etc.);

- Facial expression “uniformity” (i.e., smile, eyes expression);

- Body constitution “uniformity”.

- Age heterogeneity in the physical aspect.

Once more seeking a definition of what we perceive through the physical and chemical properties of the stimuli which may act upon our sensory apparatus, empiricism excludes from perception the anger or the pain which I nevertheless read in a face, the religion whose essence I seize in some hesitation or reticence, the city whose temper I recognize in the attitude of a policeman or the style of a public building […]. Perception thus impoverished becomes purely a matter of knowledge, a progressive noting down of qualities and of their most habitual distribution, and the perceiving subject approaches the world as the scientist approaches his experiments.(pp. 27–28)

4. Going beyond Gender and Skin Color: How Images Exceed Expectations

- Physical characteristics: including all the words, which refer to physical elements (i.e., eyes, sex, skin, nose, mouth, etc.).

- Adjectives: including all the adjectives designed for any person.

- Non-physical characteristics: including words referred to other subject’s aspects (i.e., hypothesis on their job, country of origin, religion, name, etc.).

- -

- The beard and the moustache for the light skinned man (66 words);

- -

- The skin for the dark skinned woman (70 words);

- -

- The hair for the light skinned woman (59 words);

- -

- The skin for the dark skinned man (63 words).

5. Conclusions

Objective thought is unaware of the subject of perception. This is because it presents itself with the world ready made, as the setting of every possible event, and treats perception as one of these events. For example, the empiricist philosopher considers a subject x in the act of perceiving and tries to describe what happens: there are sensations, which are the subject’s states or manners of being and, in virtue of this, genuine mental things. The perceiving subject is the place where these things occur, and the philosopher describes sensations and their substratum as one might describe the fauna of a distant land—without being aware that he himself perceives, that he is the perceiving subject and that perception as he lives it belies everything that he says of perception in general.(p. 240, 1996) [52]

References

- Thomas, N.; O’kane, C. The ethics of participatory research with children. Child. Soc. 1998, 12, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P.; James, A. (Eds.) Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 075070974X. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A.; Lindsay, G. (Eds.) Researching Children’s Perspectives; Open University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; ISBN 9780335202799. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, S. Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood 2002, 9, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, D.; Fingerson, L. Interviewing children and adolescents. Handb. Interview Res. Context Method 2002, 1, 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J.; Zamorani, E. Lo Sviluppo Mentale del Bambino e Altri Studi di Psicologia; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1967; ISBN 8806155261. [Google Scholar]

- Young, L.; Barrett, H. Adapting visual methods: Action research with Kampala street children. Area 2001, 33, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P. (Ed.) Doing Visual Research with Children and Young People; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780415431101. [Google Scholar]

- Literat, I. “A pencil for your thoughts”: Participatory drawing as a visual research method with children and youth. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Vis. Stud. 2002, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, K.; Davis, J.M.; Gallagher, M. Researching with Children and Young People: Research Design, Methods and Analysis; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781412923897. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, W.J.; Topper, G.E. Focus-group research with children: A structural approach. Appl. Mark. Res. 1998, 28, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kirova, A.; Emme, M. Fotonovela as a research tool in image-based participatory research with immigrant children. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2008, 7, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J., Jr. Photography in anthropology: A report on two experiments. Am. Anthropol. 1957, 59, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, L.; Mariotti, S. Vocabolario Della Lingua Latina; Loescher: Bologna, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, F.; Barker, J. Contested spaces: Children’s experiences of out of school care in England and Wales. Childhood 2000, 7, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damisch, H. Five notes for a phenomenology of the photographic image. October 1978, 5, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. La Conoscenza Della Conoscenza; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 1993; ISBN 9788807080760. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, J.; Miller, M.L. Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1986; ISBN 9780803924703. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 2, pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M.; Barret, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Losa Angeles, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 1412974178. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Qualitative Research; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1473916569. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, L. “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, I. Qualitative Data and the Subjectivity of ‘Objective’ Facts; Statistics in Society: The Arithmetic of Politics; Arnold: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, L.; Gough, B. Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-632-06414-4. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L.; Scannell, A.U. Planning Focus Groups; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 076190817X. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, S.; Schumm, J.S.; Sinagub, J.M. Focus Group Interviews in Education and Psychology; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978080395893. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini, L.; Rania, N. I focus group-uno strumento per la ricerca qualitativa. Animazione Soc. 2001, 2, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C.; Kools, S.; Krueger, R. Methodological considerations in children’s focus groups. Nurs. Res. 2001, 50, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammuner, V.L. I Focus Group; Società Editrice Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2003; ISBN 9788815084941. [Google Scholar]

- Albanesi, C. I Focus Group; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.E. Interviews and focus groups with children: Methods that match children’s developing competencies. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2012, 4, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 1483365247. [Google Scholar]

- Contini, M. Categorie e percorsi del problematicismo pedagogico. Ricerche di Pedagogia e Didattica 2006, 1, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K.; Barber, E.G. Viaggi e Avventure Della Serendipity; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2002; ISBN 9788815063328. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, F. L’intuizione Nella Ricerca Scientifica: Breve Percorso fra Metodo, Creatività e Serendipity. In La Creatività—Dote Individuale o Prodotto Sociale? Quadrio, A., Puggelli, F.R., Eds.; ISU Università Cattolica: Milano, Italy, 2003; pp. 193–208. ISBN 9788883112416. [Google Scholar]

- Lupo, L. Filosofia Della Serendipity; Guida Editori: Napoli, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788866661788. [Google Scholar]

- Mulaik, S.A.; James, L.R. Objectivity and Reasoning in Science and Structural Equation Modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues and Applications; Hoyle, R., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 0803953186. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, J. Suspensions of Perception; MIT: Cambridge, UK, 2001; ISBN 9780262531993. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Taylor and Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0203994612. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; ISBN 9789507247002. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, P.; Rowan, J. (Eds.) Human Inquiry: A Sourcebook of New Paradigm Research; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1981; ISBN 9780471279365. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, E.F. Reflections on Gender and Science; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1985; ISBN 9780300036367. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity; Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 9780553137248. [Google Scholar]

- Tammivaara, J.; Enright, D.S. On eliciting information: Dialogues with child informants. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 1986, 17, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.D. The autodriven interview: A photographic viewfinder into children’s experience. Vis. Stud. 1999, 14, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstman, M.; Bradding, A. Helping children speak up in the health service. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2002, 6, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, K. Places for children–children’s places. Childhood 2004, 11, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, M. Photo interviews: Eliciting data through conversations with children. Field Methods 2005, 17, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. op. cit. 1996; ISBN 0415834333.

- Epstein, I.; Stevens, B.; McKeever, P.; Baruchel, S. Photo elicitation interview (PEI): Using photos to elicit children’s perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, L.S. Reflecting on the use of photo elicitation with children. Nurse Res. 2015, 22, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, J.; Weller, S. “Is it fun?” Developing children centred research methods. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2003, 23, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdottir, J. Playschool in pictures: Children’s photographs as a research method. Early Child Dev. Care 2005, 175, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, L.M. Child-centered? Thinking critically about children’s drawings as a visual research method. Vis. Anthropol. Rev. 2006, 22, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A. Per una pedagogia interculturale. Dalla Stereotipia Dei Pregiudizi All’impegno Dell’incontro; Bononia University Press: Bologna, Italy, 2003; ISBN 9788873950189. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardellini, M. Using Photos in Pedagogical and Intercultural Research with Children. Images and Research: Between Sense and Reality. Proceedings 2017, 1, 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090926

Cardellini M. Using Photos in Pedagogical and Intercultural Research with Children. Images and Research: Between Sense and Reality. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):926. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090926

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardellini, Margherita. 2017. "Using Photos in Pedagogical and Intercultural Research with Children. Images and Research: Between Sense and Reality" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090926

APA StyleCardellini, M. (2017). Using Photos in Pedagogical and Intercultural Research with Children. Images and Research: Between Sense and Reality. Proceedings, 1(9), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090926