1. Introduction

Carlo Mollino, active in the fields of architecture, design, literature and photography, often worked at the intersection of these disciplines. Narrative and scenography characterize Mollino’s photographic and architectural work. They create narrative paths in their visual storytelling. This paper investigates the interrelation between the different media used to tell the story of the bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields. It is argued that in this specific case, text, image and drawing—images of intangible heritage, together give rise to a form of autobiographic architecture.

Bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields in first instance is a work of ‘paper architecture’ as it is a design commissioned by

Domus, to be communicated with a wide architecture audience. For its

Soluzione Tipiche series,

Domus invited architects to propose original design solutions for typical living spaces such as bedroom, dining room, living room. An introductory text by

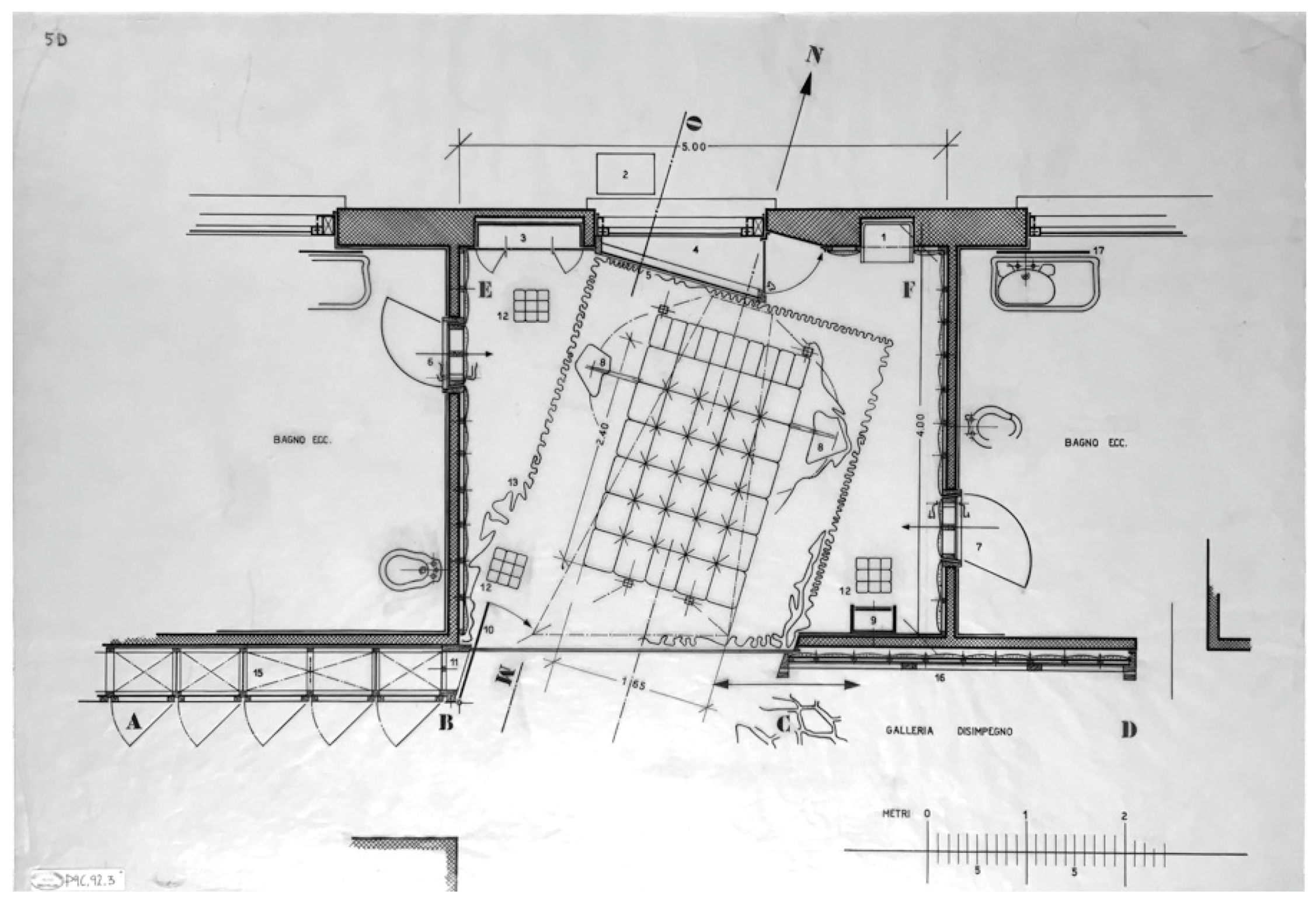

Domus editor Melchiorre Bega sets out how Carlo Mollino and two other teams of architects—Paniconi, Pediconi and Angeli, De Carli, Olivieri—were given a generic rectangular space measuring 4 × 5 m to ‘make a personal contribution to the solution of the question of the house, with the greatest freedom of conception’ [

1] (

Appendix A, 1). Their personal interpretation of the assignment is expressed in the titles of the projects:

Bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields, Bedroom for the countryside, and

Bedroom for a sportive couple. Mollino proposes a bedroom in a row of rooms leading into a gallery. The bedroom is accessible through three doors: a big sliding door opens onto the gallery and two side doors connect to two lateral bathrooms (

Figure 1). Encapsulated by a tent-like structure that creates a soft cocoon within the bedroom, the bed takes on a central position. This ‘four poster bed’ is rotated in order to orient the bed’s head to the north, creating two trapezoidal spaces to the left and right of the bed, as for Mollino, ‘architecture is born from the accident’ [

2] (

Appendix A, 2). Bega transposes this to the readers of

Domus: ‘Accident that—in your particular case—will be represented by your personality, your apartment, your life-style’ [

1] (

Appendix A, 3). Still, it becomes evident that Mollino’s atypical proposal of a ‘bed-cocoon’ has an ironic, extravagant and highly personal undertone.

Mollino’s

bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields has caught scholarly attention as a peculiar project. It has, however, not been researched in depth. Architectural historian Imma Forino, active in the field of interior studies, identified the

bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields as a ‘micro cosmos bed that serves as a cocoon’ and noted that ‘Mollino seems to have re-invented a typology of the past—the bed with independent curtains—mediating it through a personal surrealist patrimony of ideas and imagination’ [

3] (

Appendix A, 4). This paper further investigates the personal framework of the bedroom’s author through an interpretative reading of the project, thereby approaching it from the viewpoint of autobiography in architecture. To do so, the paper will present a close reading of both the project as published in

Domus (plan, section, elevation drawing, interior perspective, photograph of a mock-up and concept text stating Mollino’s design intentions) and the preparatory drawings and photographs held in the

Carlo Mollino Archives (ACM) (

Appendix A, 5: English translation of full concept text).

The paper takes the highly subjective space of the cabinet as a hermeneutic tool to look at Mollino’s bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields. In doing so, the paper refers to the writing of cultural critic Walter Benjamin on the retreat of the private individual from the real world into the 19th century interior, and architectural historian Georges Teyssot’s reading of Benjamin focused on boredom and inwardness. In relation to the personal space of the bed, the paper finds a frame of reference in the writings of French essayist Georges Perec as well as in the work of architectural historian Beatriz Colomina and philosopher Paul B. Preciado who introduce the notion of the space of the bed as a machine for creative production, experiences and gender. In light of the often singularly erotic reading of Mollino’s interiors, the sexual connotations of the bed cannot be overlooked. Although notions of sexuality, power and desire are present in the project, the paper chooses to approach Mollino’s bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields in a wider sense as an autobiographic space, as the project manifests itself in the first place as an expression of the self, or the private made public.

2. Autobiographic Writing in Architecture

In looking at autobiography in architecture, a telling example employing autobiographic writing can be found in the infamous project casa Malaparte, where the house becomes an expression of the owner’s personality. Curzio Malaparte referred to the house as ‘casa come me’ or ‘house like me’. (

Appendix A, 6) Malaparte identified with the house to such extent that the authorship of the house came into question: is the house the work of the architect, Adalberto Libera, or is it the work of the writer-inhabitant, Curzio Malaparte? Regardless of the answer to this question, it allows us to think about the writer and the architect, and by extension autobiographical writing in architecture. Let us here, reversely, consider Mollino the architect as writer.

Autobiography is a genre originally deriving from literature, also known as ‘life writing’ or ‘telling (part of) one’s own life’. Interestingly, at the outset of his career Mollino wrote a number of short stories meandering between fictional biography (e.g., Vita di Oberon 1933), and autobiographical novel (e.g., L’amante del Duca 1934–1936) with the architect as the protagonist. While the autobiographical genre is generally a retrospective narrative of a ‘real’ person, Mollino’s early biographical writings tell a speculative life story through a fictional protagonist. Oberon for instance acts as Mollino’s alter ego: a young architect, who dies at the age of 26, having imagined (many) and built (few) works of architecture, while in L’amante del Duca, the protagonist is architect-count Fausto.

Despite its factual claims, autobiography is inevitably constructive or imaginative and resists a clear distinction from fictional biographies. Autobiography is often seen as ‘highly manicured’ or as ‘publicity-geared self-edition’ rather than as a veritable confession (cf. Dimitrakopoulus 2017) [

4]. It is argued that in

bedroom in the rice fields, Mollino’s autobiographical style is developed into an architectural project.

Designed for publication, the project has no direct client. Mollino imagines the client as follows: ‘He has an athletic temperament. When he wakes up he loves to see not only what the weather station says on the sill but also the weather itself. This explains the hinged mirror that reflects the landscape visible from the window behind the bed.

Today we are going to fly, today we’re going to eat chestnuts (…)’ [

2] (

Appendix A, 7). Knowing that Mollino would become a pilot, it is no coincidence that the male figure talks about flying. Mollino personifies the person in the bed looking into the mirror. Indeed, it is Mollino’s face we find reflected in the mirror. It is intriguing to think about Mollino the architect-pilot, or to reflect on how the physical condition of the architect can translate into a building. In the introductory text to

Wiederhall’s issue on

Autobiographical Architecture of 1988, architect and researcher Joost Meuwissen writes: ‘what sport is to the architect, is program to the building, the scenario (...)’ [

5]. The ‘I’ of the architect is of a physical condition, and corresponds with the ‘he’ in the bedroom. Mollino both acts as architect and occupant of the bedroom; he designs the space in which he would like to dwell. By Mollino’s visual narration of the story of the bedroom, we find its autobiographic plot. Mollino’s fascination for flying is not only expressed in the architecture’s program or purpose, but also translates in the design aesthetics and envisaged atmosphere of the space.

3. Bedroom Self-Portrait

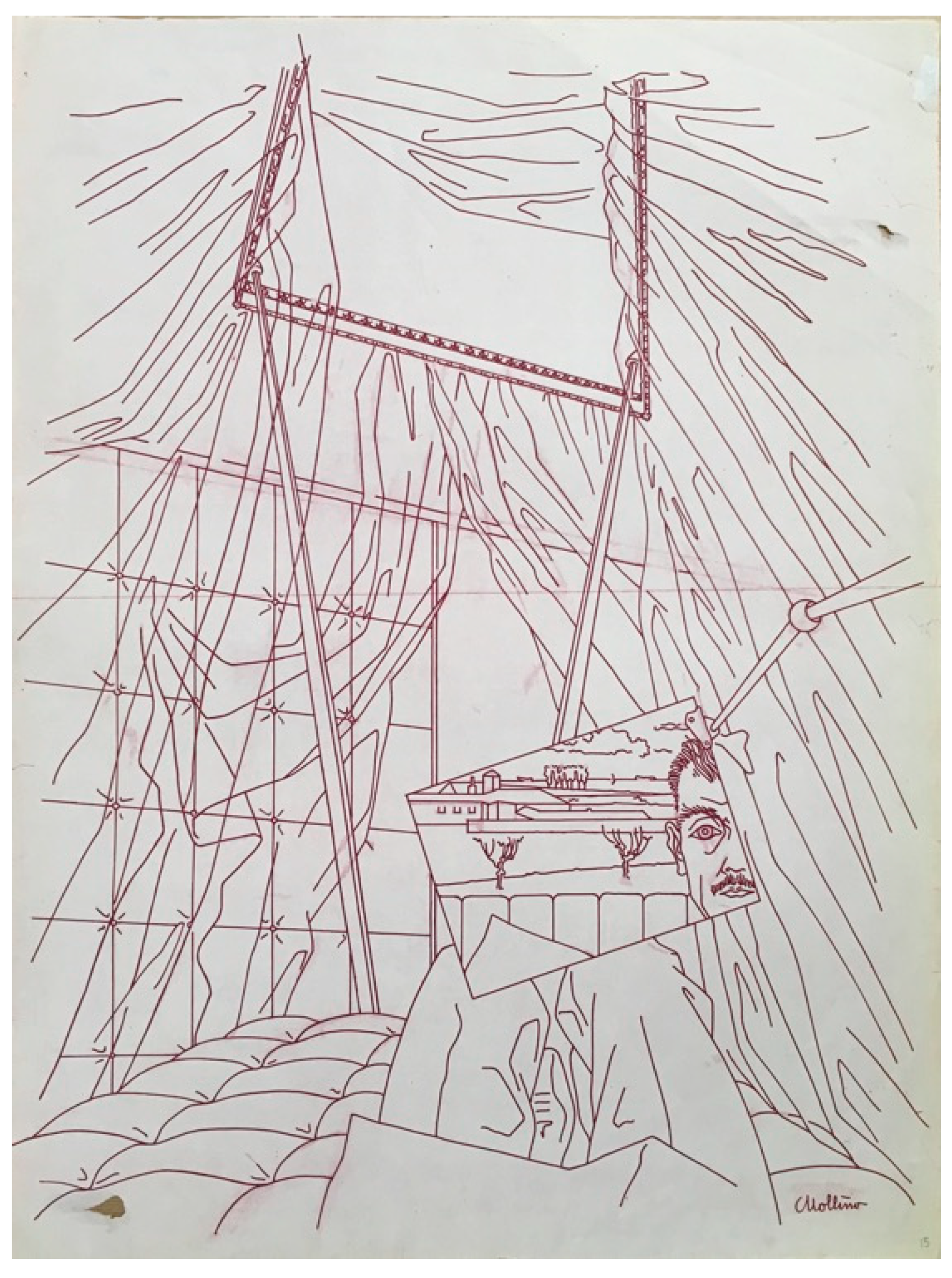

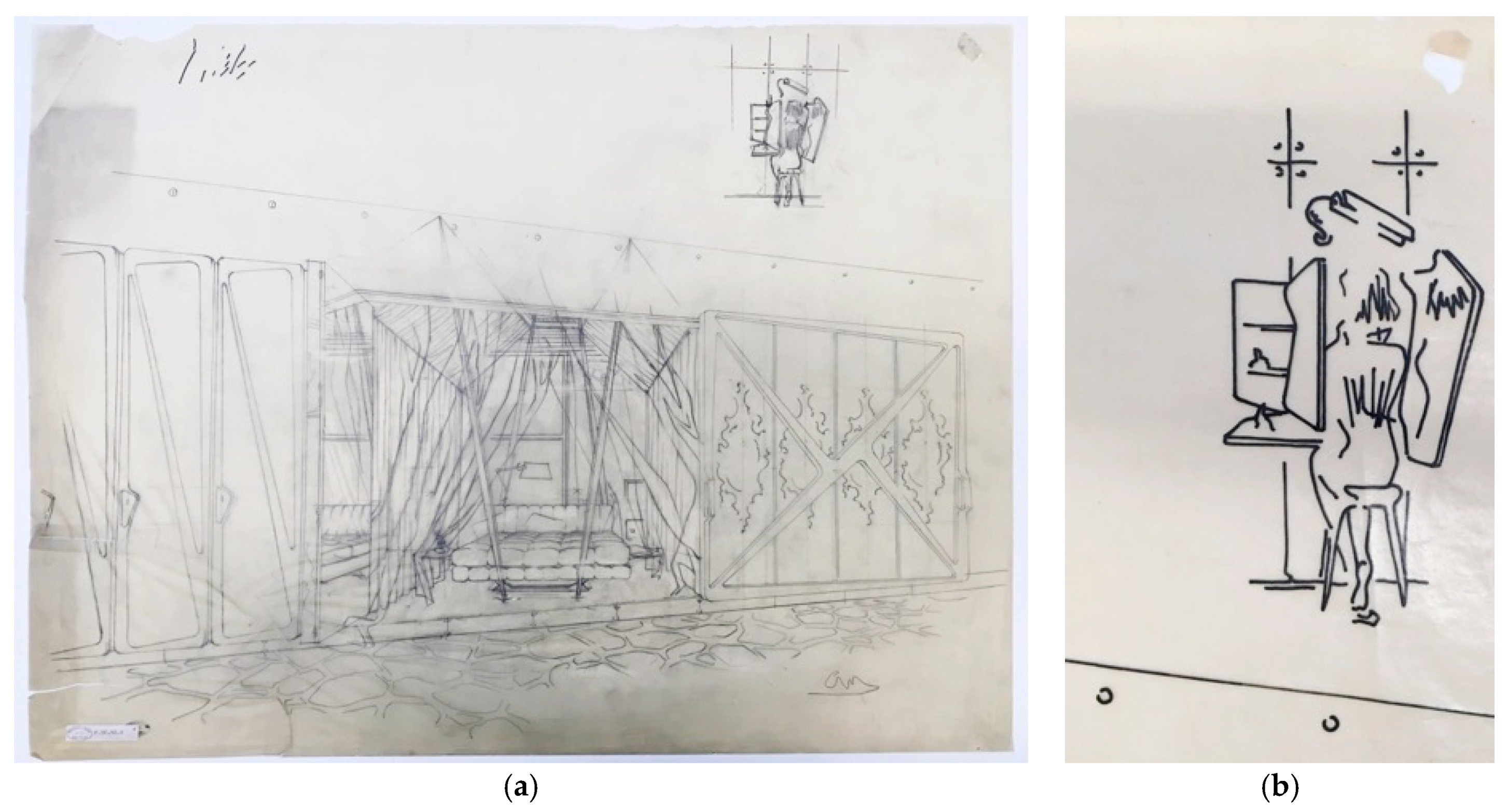

Mollino presents the

bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields and himself through one central perspective drawing (

Figure 2). Mollino is physically present in the perspective; we see part of his face reflected in a mirror, held up above his knees by a telescopic arm. The drawing is carefully composed. There are multiple perspectives at play; from a close-up of his legs resting on the bed and his face half reflected in the mirror, to the backdrop of the tent like drapes, to the distant landscape behind his reflection in the mirror, and borrowing Mollino’s words ‘to an opening above the bed offering rest to the eyes, a vault that evokes the sky’ [

2] (

Appendix A, 8). A big sheet of paper, a map or presumably the drawing that we are looking at, lies on the draftsman’s lap. The focal point of the drawing lies in the mirror, just next to Mollino’s reflection.

Generally, people figure anonymously in architectural drawings to indicate the scale and use of the space. It is rather uncommon that identifiable individuals are represented, let alone like in this case, the author himself. The author does not just figure in the representation of the space; he is its focus. How should one interpret this self-portrait inside the bedroom? Does Mollino present himself as the architect, artist, or private dweller?

We can think of various examples of 20th century architects representing themselves through their projects. The architect is presented as master of the building, often expressed by the architect posing by, holding, looking, or pointing at the architectural model (

Appendix A, 9). Mollino’s self-portrait in the bedroom captures him in his space, as both author and user. Mollino takes a highly personal position, portraying himself in probably the most private of places: his bed. There is a certain contradiction in this self-exposure from a most intimate space—much similar to today’s—

selfies in bed—that by ‘exposing one’s person’ touch upon exhibitionism and voyeurism.

The self-portrait is as a subject at home in the arts—as photograph or painting—and in the private domain—as photographic self-portraits. Characteristic to these self-portraits is the self-editing aspect; the subject carefully constructs the representation of the self and the surrounding space to communicate a material (status) or emotional (state of mind) position. Mollino’s self-portrait in the center of the farmhouse bedroom in the rice fields seems to be no exception.

Mollino experimented with photographic self-portraits throughout his career. There is the series of portraits taken in Casa Miller, with his artist-friend Italo Cremona, in which various objects such as shells, gloves, and plaster casts figure in ever changing constellations. There are self-portraits in which Mollino seems to identify with symbolic objects such as the self-portrait with a multi-facetted glass ball—Mollino as multifaceted personality—and portraits wearing a flying helmet and glasses in front of an areal view of Manhattan—Mollino as pilot. Frequently, Mollino takes his self-portraits with the aid of a mirror. Mollino chooses to show the mirror, emphasizing that he is looking into the mirror and capturing his self-reflection.

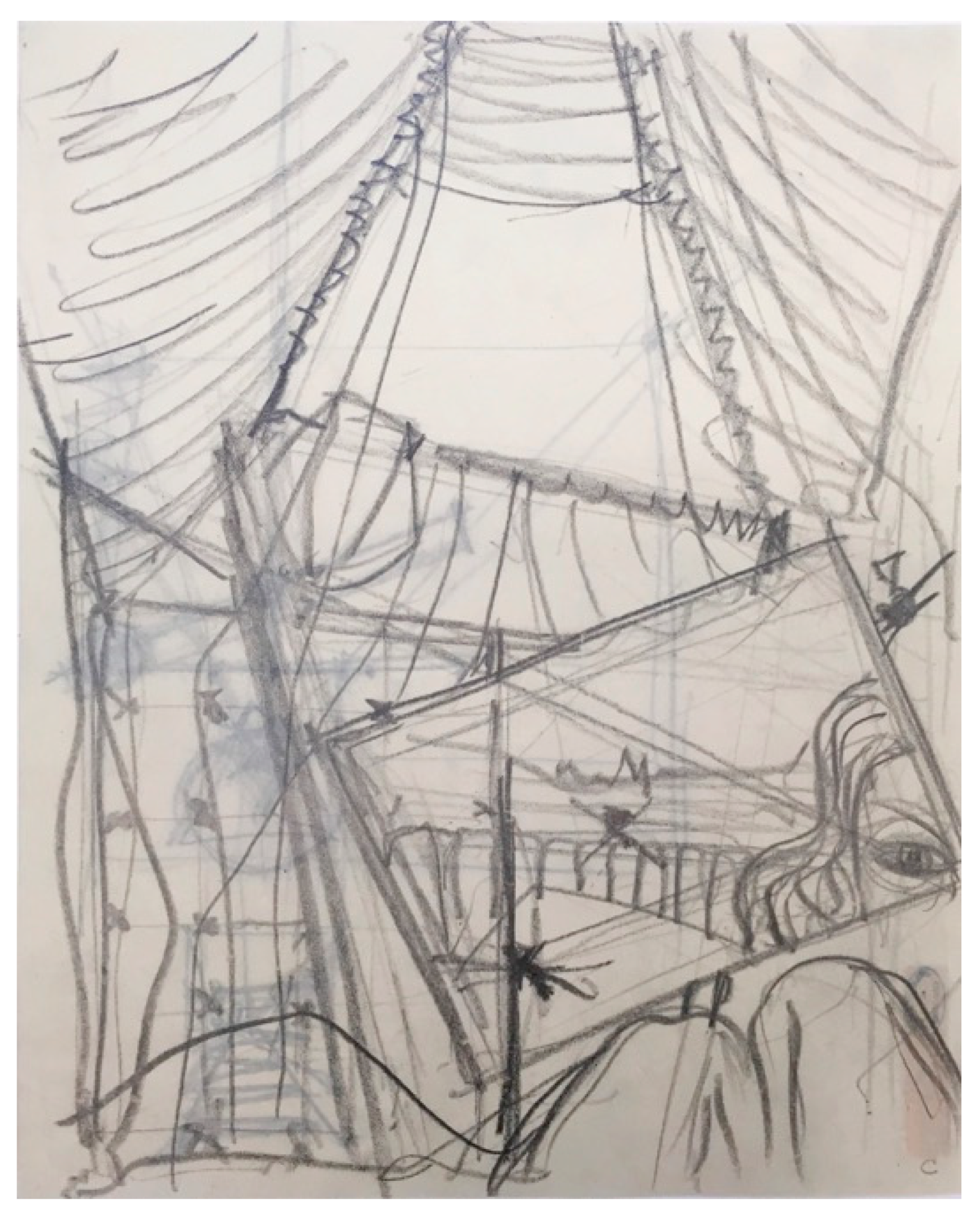

The central perspective published in

Domus is the result of various draft versions, from hazy pencil strikes to clear lines in ink, tracing the essence of the drawing. In the series preceding the final perspective drawing for publication, there is one clear exception. In one pencil sketch, Mollino’s face is replaced by the suggestion of a feminine face (

Figure 3). An oval eye, with wavy hair around the temple, gazes back in the mirror—Mollino as a woman. Still, the pair of legs in trousers visible underneath the mirror has not changed, we only no longer see the shoes. The drawing holds certain ambiguity towards the person on the bed.

4. Cabin, Capsule, Cocoon, Cell for the Senses or Cabinet

‘The interior is not only the universe but also the etui of the private person.’(Benjamin 2002) [

6] Mollino describes the bedroom as a ‘cabin’, thereby likely referring to its formal articulation, as a row of rooms served by a gallery, but possibly also to its function as (male) ‘cabinet’ or sleeping place. Mollino places the cabin in the rice fields as a shelter against ‘mosquitos as big as sparrows, (…) locusts and frogs’. Mollino continues to write: ‘A better term for this cabin might be hot air balloon’, thereby referring to the further segmentation of the space with curtains, which create a second mobile and soft shell, moving in a mechanically generated breeze. For Mollino these have twofold purpose: ‘(…) the mosquito net has its practical as well as psychological function:

sealing yourself up in a cocoon and, at the same time, being able to

look out onto the world’ [

2] (

Appendix A, 10). This description seems fitting with Paul B. Preciado’s understanding of the

cabinet as a

cell for the senses [

7].

One can enclose oneself in the soft multi-layered cocoon of drapes and by closing the big soundproofed sliding door, padded from the inside, shut out the world. To design and publish a sensuous bedroom during wartime is in itself an act of escapism. In the farmhouse bedroom in the rice fields, Mollino controls the perception of reality by directing the gaze. The outside world is filtered; we only see part of the view from the window reflected in the mirror (

Figure 4). Borrowing George Teyssot’s words on mirrors: ‘If the windows are mirrors, perhaps the exterior is a total illusion; there is no outside world’ [

8]. The interior space is turned into itself, to the self, and at the same time, through reflection opened endlessly. The bedroom counts five mirrors: a hinged mirror above the bed, a pivoting mirror at the threshold between bedroom and gallery, a

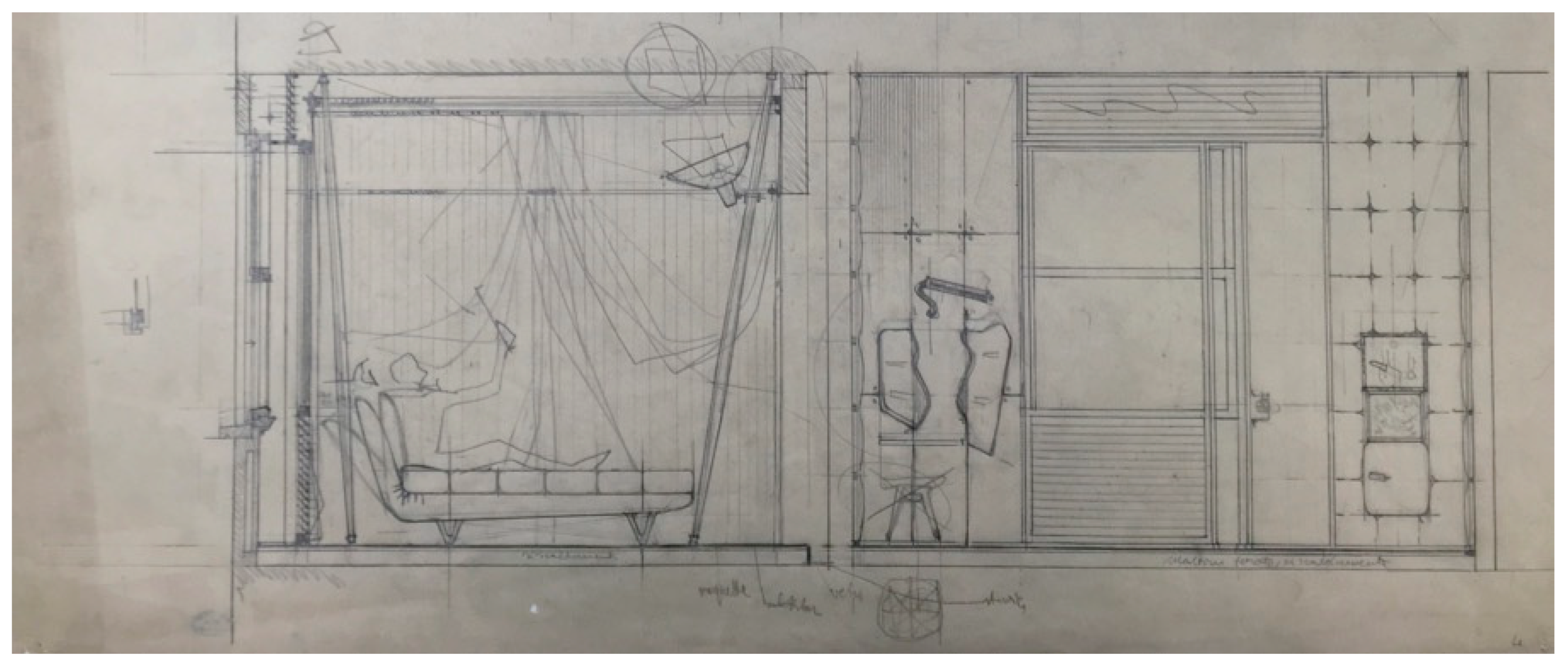

psyche and mirrored wall to the left of the bed head and a cabinet hidden next to the sliding door. The bedroom functions as an optical device with extreme visual complexities.

The visual and functional focal point of the space is the person lying on the bed. The bedroom is like a control room, fully fitted with the latest technologies. There is a certain contradiction in the idea of a frugal life in the farmhouse bedroom and the abundance of technologies, from electrical lighting to mechanical ventilation. Perhaps the focus on the application of technologies in a domestic environment can, partly, be explained by the intention of

Domus to offer its readers modern and applicable solutions for the home. The technologies are installed for the pleasure of the resident of the

bedroom of the farmhouse in the rice fields. A detailed section drawing reveals the hidden mechanics of the cell: a Knapen ventilation system, a mini-max icebox, food warmer and dumb waiter mounted into the wall, two glass side tables on swiveling arms, a barometer and a hinged mirror. From the bed one enjoys a pleasant current, food is provided, cups are within arm’s reach and the view out of the window is facilitated. In this, Mollino seems to create a futuristic image, as if anticipating Beatriz Colomina’s present-day theory on

The Century of the Bed, in which ‘(…) technologies have removed any limit to what can be done in bed’ [

9]. The need to leave the bed is reduced to a minimum, the bed made most comfortable, allowing boredom to set in. Boredom, in Georges Teyssot’s understanding, is the stabilization of pleasure. In his pleasure room, Mollino sits clothed in bed, gazing in the mirror. Mollino seems to be awaiting something or someone. This moment of boredom is situated in the present, as an in-between state. Mollino seems to be daydreaming, perhaps imagining travels from the

hot air balloon. Or like Georges Perec describes his ‘in bed’ childhood memories: the ‘bed-nomad travels a great deal at the bottom of the bed’ [

10].

5. A Place for Two: The Other and the Self

‘The

bedroom is for a young, serious and happy couple’, Mollino explains in his concept text [

2] (

Appendix A, 11). Next to Mollino’s presence, there are clear indications of another (expected) presence. Looking at the plan, we see the bedroom is set in the middle of a row of rooms served by a gallery. The bedroom has three doors: the big sliding door, and from each side, hidden behind the drapes of the four poster bed, a door leading to a bathroom, one for him and one for her. By orienting the bed to the north, Mollino created two trapezoidal spaces between the mosquito net and the padded walls of the cabin. These in-between spaces behind the screens make up two grooming areas. The ritual of

going to bed seems to gain extra meaning. A last step in the process of

getting ready for bed is to look into the mirror. Stepping out of the wings into the bed is like appearing on stage. Mollino hints at the backstage presence by drawing a lady figure in the margin of the main vista. This little drawing of a lady seen from the back and seated at the

psyche mirror, is seemingly a rapid sketch consisting of a few lines. Looking at all versions preceding the final outer vista, we find that the small drawing is always there, and together with the main vista crystallizes further each version (

Figure 5). The little drawing is carefully constructed and contains for Mollino essential information.

Who is the woman in the bedroom in the rice fields? Although the floor plan suggests equality between the male and female occupant—two mirrored bathrooms, two grooming areas—Mollino is very much in control. His voice is articulated in the design and he operates the mirror on the telescopic arm. Is the woman imagined by Mollino and thereby a projection of himself? The reflection of the female visage appears on his position in the bed. It is interesting to consider here Malaparte’s

Woman Like Me of 1940. Malaparte describes the likeness of a woman to himself ‘to be able to be proud of her, to love her like I would love myself, if I were a woman’ [

11]. Where Malaparte constructs a literary identity with the words

Like Me, Mollino seems to do so through architectural design. The

other in function of the self.

6. Confessing Colour

Although the bedroom in the rice fields can be called a work of

paper architecture made for publication, the project was temporarily and partly materialized. Mollino wanted to test the bedroom in real space—and take a picture of it—and staged the bedroom in an interior space, presumably his own bedroom. The project thereby turns inward even more. Its materials are made tangible. The juxtaposition of soft textures on the floors and walls, on curtains and the bed, intensify the sense of touch (cf. Preciado 2013) [

7]. The fluent, semi-transparent and heavy opaque drapes form a secondary mobile and soft wall, controlling sight, temperature and sound, thereby intensifying the experience of interiority. The architectural drawings translate the sensation of touch into vision.

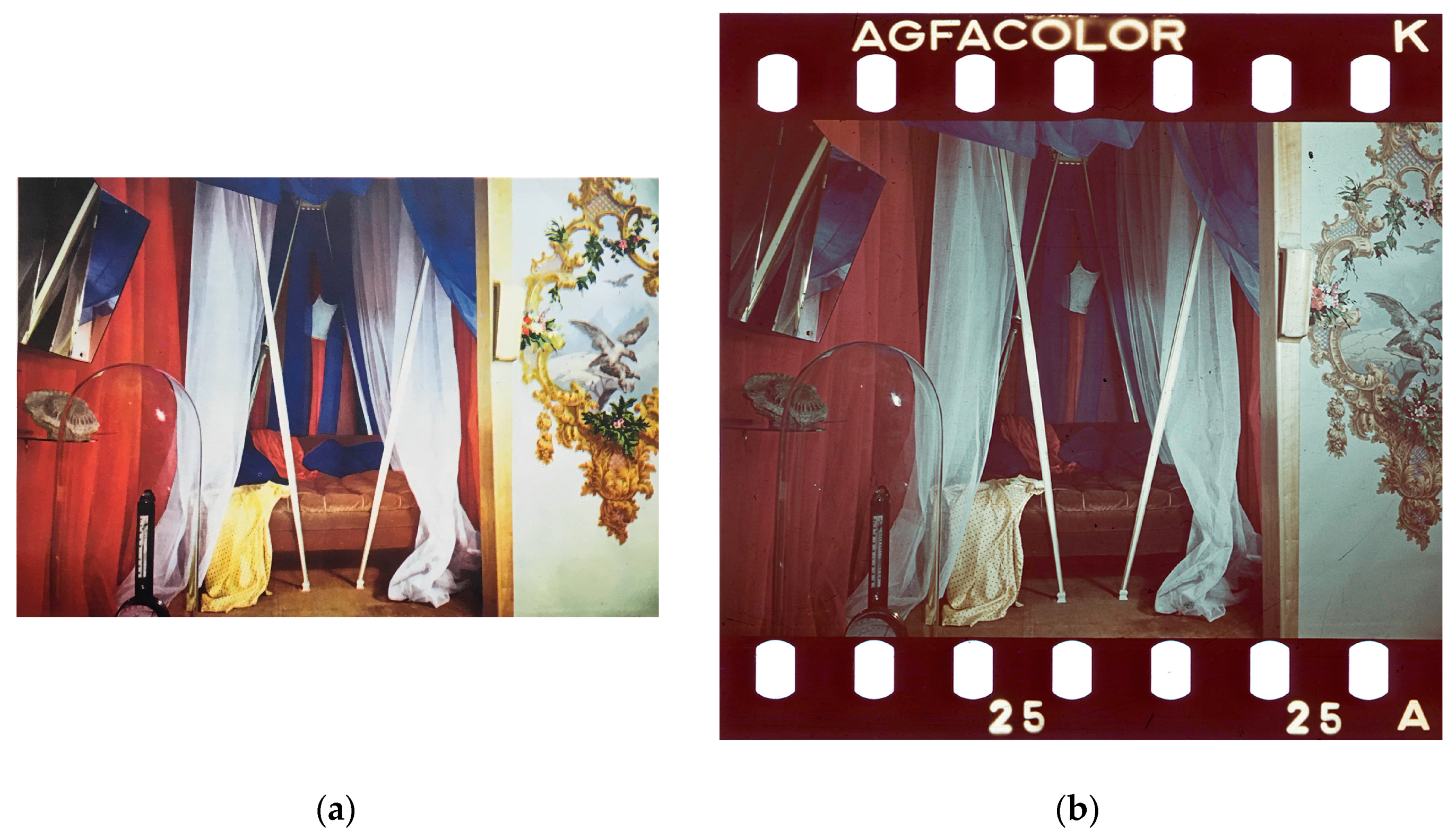

The

Domus publication shows a photograph offering a glimpse into the cocoon around the bed (

Figure 6a). In the front of the picture plane we see a fragment of the sliding door. Mollino describes how the door decorations of ‘early 19th-century panels with beautiful colours would have been a waste to throw out just because they do not correspond to the

style of the room’. Indeed, the panels were already in Mollino’s possession, we find them on black and white pictures of his bedroom in his parental house. The panel in view shows a mountain scene in which a bird falls prey to a predator, while a third bird circles high above. There is no such thing as coincidence in Mollino’s work. The scene on the door panel surely holds a key to what happens inside.

The colours are strikingly vivid. Mollino is known to have a great and daring sense for colour. They correspond to Mollino’s description: ‘The rectangular space of the ‘bedroom’ is comprised of red, semi-transparent fabric draped like a tent from a trapezoidal frame suspended from the vault (…). The inner mosquito nets are light grey and blue’ [

2] (

Appendix A, 13). The colours of the original photographs are notably less vivid than they appear in

Domus, suggesting a recoloring during the publication process (

Figure 6). The possibilities of colour print also seem maximally explored in the section drawing with coloured lines. The colour and texture of the mattress is unexpected, brown velour. (

Appendix A, 14) There are no sheets on the bed. Some colour accents are added: dark blue pillows, a red cloth and what looks like a brown dotted yellow dress. A colour accent or trace of seduction?

7. Autobiographic Architecture

The analysis of the project for a farmhouse bedroom in the rice fields shows that autobiographical design situates itself in different media: from autobiographic writing in architecture, to portraits of the self in architecture (both drawing and photograph), to the insertion of objects with personal meaning to it in the interior. It is the presence and narration of a self-edited author in all these segments that make up autobiographical architecture. From the design of the bedroom we can distill certain subjects that seem to function like instruments in the narration of the self: the interior, the mirror and the bed.

The design is foremost an interior design. The relation of the bedroom to the other rooms of the farmhouse is not evident. Apart from the baroque paneling of the sliding door and the row of wardrobes giving onto the gallery—both elements originally stemming from interior space—we do not know what the building looks like from the outside. Like the archetype of the cabin, the first function of the project is to give shelter, to create a place where one can enclose oneself in. There is no direct relation with the exterior. Isolated and reflected, the view outward is mediated through the mirror. Looking into the mirror, we find the semblance of things.

Mollino imagines and maintains his personal narrative within the interior of the bedroom. The interior coincides with interiority, or the inner life of the occupant. The bed takes a central position and as the most elementary space of the body it constitutes what Perec calls the individual space par excellence. From the bed Mollino constructs his personal narrative.

In the bedroom for a farmhouse in the rice fields, the architect meets himself in the mirror. In designing this space, Mollino has seduced himself in the pleasure of looking and watching himself look. Through publication in Domus, Mollino transmits this (imagined) experience to other architects. It is an autobiographic account constructed and expressed in architecture.