1. The Digital Turn

When Benjamin [

1] tried to set out the loss of the aura within the work of art thanks to mechanical reproduction probably could not forecast the spread of the so-called digital revolution and even less the 2.0 communication in contemporary world. Few years after the dark outlooks about the “

digital divide” [

2], between who could have access to the digital data flow and who could not afford it, the use itself of the web space has taken a widespread inter-ethnic and inter-class role. Owing to the last economical, technological and political development the interconnected cyberspace drives digital flows to involve even the most isolated places of the planet as well as every social class. One of the most striking outcomes is the exponential progression in the production of contents that are uploaded, duplicated, shared, commented, exchanged, hybridized on the web. Among such contents a considerable part is taken by images. From the analysis of the daily web communication it is possible to outline meaningful issues that seem to disclose a new layer of virtual existence of images depicting a parallel visual reality.

Many scholars tried to point out similar aesthetic shifts. Since Gilbert Cohen-Séat [

3] spoke about “

iconosphère” from a quantitative and qualitative point of view it has been discussed about an environment that changes the conditions of reception and presentation of the image. Although the reference was at that time focused on cinema it gave rise to a tradition of interest for visual media which follows a line of reasoning from Eco’s “

apocalypse postponed” [

4] to Fulchignoni’s

Civilization de l’image [

5]. Régis Debray [

6] used the word “

vidéosphère” to show how the visual side of the human experience definitely overcomes the writing, the “

graphosphère” and after that he proposed the concept of “

médiasphère” to reflect the diffusion of media and connectivity. Later Louise Merzeau [

7] coined the term “

hypersphère” to claim the widening of an ubiquitous visual culture that nowadays cannot be linked anymore only to television, advertising or generic visual products so that only avant-garde artists should be able to detect it. But the question is definitely still open how we will see.

3. Image and Cyberspace

What could be the most outstanding features of these new web-based images? And, moreover, what are the determinants most strictly connected with their being digital and with their showing up on the net in comparison with the mechanical reproduction considered by Benjamin? And finally what could be the side effects on the in-depth perception by the users of the web tools?

Basically this new kind of reproduction cannot be put in comparison with the analogical one in terms of quantity and speed. We are nowadays in front of a stunning amount of images uploaded on the net and no software will ever be able to sound it out or to process thoroughly. The number of the so-called “selfies”, just to give an example, is estimated around 24 billion and it will take four centuries to be completely checked [

15]. Beyond exhibitionism, self-indulgence, request for ego gratification and social need of sharing the quickness with which instantaneous digital portraits are born and entrusted to the web definitely overcomes the power of every analytical web-tool. A distinguishing feature of the relation between user and content is the asymmetry between access to the Net and web diffusion. The web user, who upload an image (of itself, its environment, space, creations etc.) to the Net, knows the entry point but not the leaks of exit. Or rather it is impossible to be aware of its destiny.

The Internet is in fact an open labyrinth with unknown paths which take to unpredictable destinations. The user voluntarily accesses the web and exposes itself and its works, productions, elaborations to a global and anonymous audience. An audience that is not only a passive consumer but often a maker in turn who can share, misappropriate, plagiarize, disprove, edit, enrich or spoil the image after it is left to the digital sphere. The flow of images is actually out of control and even Getty Images [

16], the biggest professional image provider of the world, decided to declare 35 million pictures royalty free on 80 million owned. This decision was taken after realizing too many images were used without consent and considering every effort to stop legally this practice definitely useless.

So some pictures with a great visual impact can be easily retrieved in a considerable amount of copies with slight differences owing to the continuous process of digital format conversion or duplication and the number of reproductions coming from different sites can be evidence of the plain success of an artist. It is the case of the neo-surrealist Vladimir Kush: a screenshot of one of his works reminds in some way to an evocation of Andy Warhol’s famous silkscreen paintings of Marilyn Monroe (The Marilyn Diptych at Tate Modern) or Mao (A picture of Mao by Warhol was recently sold by Sotheby’s at

$ 12.6 million) on the domestic display (

Figure 1).

The case of the work of art entrusted to the Net is probably one of the latest outstanding features of a new sort of “obliged museum” [

17] fostered by the digital environment for the nomadic people of the web. Virtual galleries are today a common way to present authors and works. In this regard it is interesting the case of the website “Celeste” [

18] which can boast 75,000 personal web-pages and 70 million on-line visits. The idea of a on-line gallery in the form of an international web community to promote young artists or events, organize exhibitions, host blogs and share projects can be resumed in its motto: “

you deserve to be seen”. On the other hand, thanks to the Net, the effect on artworks and art-making can be immediately understood by everyone through a quick survey on a personal computer using key words (names, titles of the artworks, periods, styles etc.) although the relationship between artists, tastes of the public and art fruition is probably a more complex and important issue which would require sophisticated and advanced analysis tools form several disciplines.

4. Technology and Bottom up Production

As the virtual space is a boundless land and most of all open to all types of recordings what effects can it have on the aesthetic and creative experience of the hyper-connected mind at the present time? Marshall McLuhan [

19] claims that new media and technology modify and enlarge our psychological and social asset. Even if the thought of one of the cornerstones of media studies can nowadays be criticised as technological determinism it is a fact that the web has turned and reinvented our sensorial and creative experience [

20]. New competitions, for example, are taking place for short movies shot by mobile [

21] with open sharing, voting possibility and with only three guidelines: one mobile, one minute, one film. In the same way the new opportunity to take photos by drone, tanks to the decreasing cost of this device, can be evidenced in a set of contests or specific websites: “Sky Pixel Photo” [

22], “Photography Awards Drone International” [

23], “Dronestagram” [

24]. Some art photographer, such as Aydin Büyüktaş [

25] for example, started to focus on the innovative side of aerial views granted just by the drone technology. It is plain and clear that the development of technical resources has an influence on the contemporary imagery. This is not a totally new phenomenon actually. The fascination for instantaneous or distorted images by mobile or drone finds a precursor in the role of analogical photography on impressionism as well as the first view from planes on futurist “

aeropainting”. But the spread of open data and open source software is probably more important from the point of view of digital flows. The main feature is the process of democratization of creative software: from the most simple to professional one the opportunity even for non-expert producers to give their contribution is as great as never before. A contribution, and this is another crucial issue, that can meet a virtual endless public of users and consumers in the cyberspace of the Net. The web-user is actually evolving in parallel with the power to record, modify and customize contents thanks to the development of technological tools.

The important question is the co-evolution of the two sides of the relationship: the request for a space by the virtual people fosters and improves the digital platforms that are compelled in turn to offer new opportunities, incitements and suggestions. Many kinds of images can be produced and edited: three-dimensional, bi-dimensional, parametric, vectorial, raster, with open or closed format, with more or less experience and background required. Both professional and amateur graphic designers or modellers can have almost an universal range of results (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

A lot of this bottom-up productions are left to the world wide web thanks to their digital status and the constant availability of an huge amount of icons allows a new nomadic audience to surf on a virtual territory and to embrace newborn formal categories always on renovation. Every image is so an open-work and can serve as an inspiration for further reproductions. From this point of view the key concept is that a communicative system cannot be built as a solo operation. In the web a subject is accountable to others in every act and everybody has the same right: the dialogue is therefore the norm. To depict deeper this new condition the concept of “

unlimited communication community” [

26] may fit very well the new peer to peer digital relationship. The Net is so an arena open to the public game, a place for a common agreement with same rights and obligations for all. There are a lot of digital platforms to show up personal creations, photos or models (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Deviantart [

27] (self-proclaimed as “the world’s largest online social community for artists”) is only one of them. The platform host images from single authors and, as an art gallery, allows people to leave comments, suggestion or critics. The case of Deviantart shows that what were once re-interpretations of painting themes, space typologies or illustration handbook are now heritage not only for specialists but also for virtual crews who decide to share a trip through cyber galleries, to be curious as well as creative, to show up as well as to be judged by peers. So the distance between expertise and naivety is progressively shortened by a continuous process of reciprocal visual education. An evidence of this mutual affordance to envision new common perspectives can be seen in the rapid evolution of the web platforms.

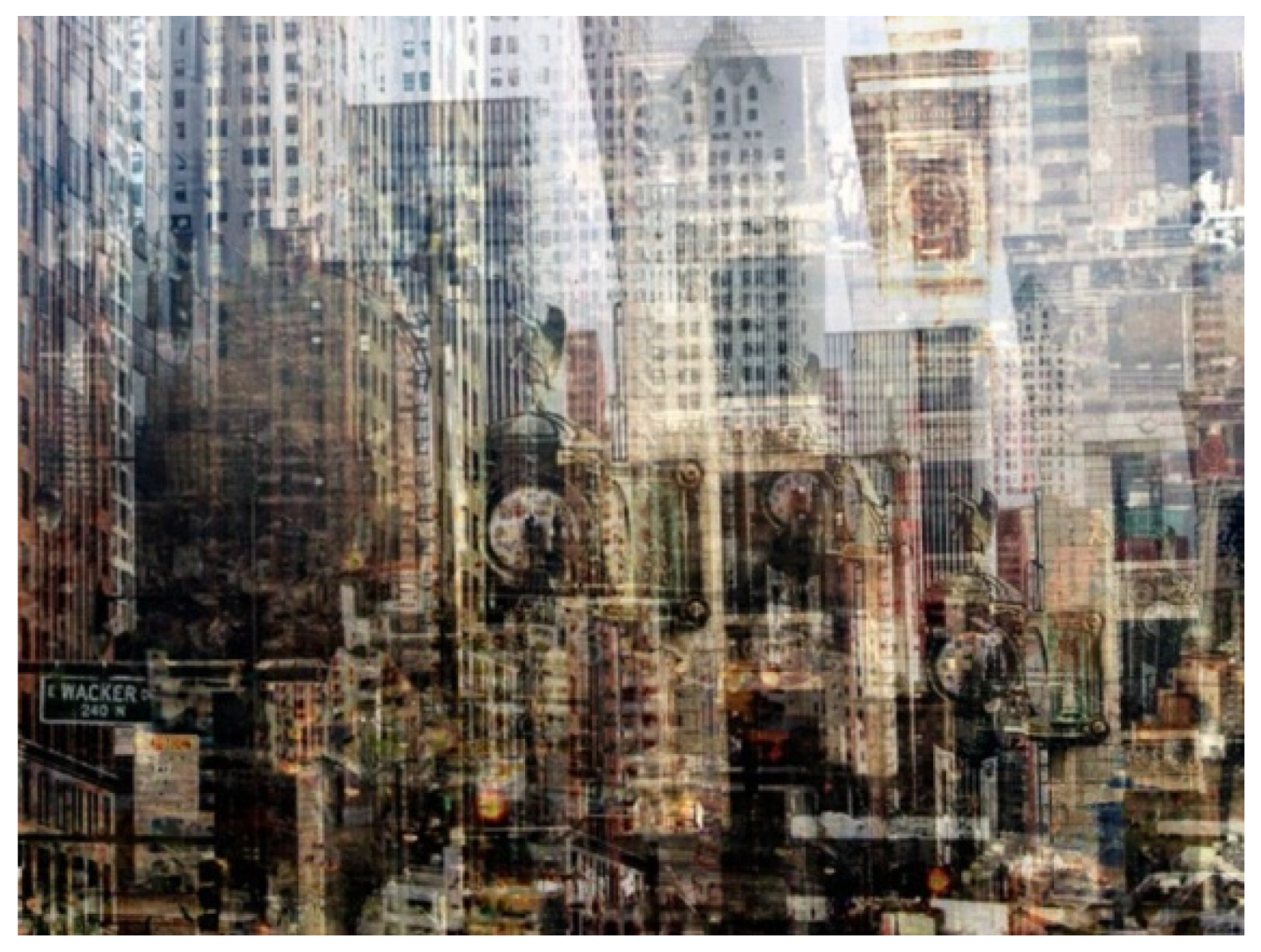

Different genealogical steps include in sequence: the blog phenomenon, Youtube, Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, Pinterst, Instagram, and so on. This kind of image collections can remind to the fascinating, and in some way surprisingly prophetic, narration of the “

Life of the forms” by Henri Focillon [

28] who focused the work of art as coming out from an obscure and blurred turmoil and belonging to a complex system of relations. In other words the extreme variety of the digital icons hosted on the web and the often unknown paths of their migration from site to site foster a new visual world through the constant liability to be modified and edited by other authors. Such an interesting opportunity given by the Net can be envisaged as a new way of icon making. The digital image can in fact have an origin that is no more limited only to one author but many steps could have been in the darkness of an unknown genealogy (synthetic authors, community of authors, unaware authors, authors staggered over time, no specific author etc.) following unpredictable processes: in other words images acquire a nonauthorial dimension. From a wider point of view it has been argued that the last aesthetic performance of the contemporary techno-anthropological condition is connected with the communication based on distance and with the aesthetic flows after the advent of the Net [

29]. And it is not only a matter of images produced by the repeating automation of programmed devices (cctv, camera-monitor systems, photocell etc. the so-called “big data”) but of a product with one or more specific origins. A good example of the new paths of the flows in art can be highlighted by the “social synthesizer” software used by young artists to perform a new idea of social life made of superimposition of urban images (

Figure 8).

This aesthetic representation and other similar ones express in some way an incoming sensibility to evoke a new visual territory of images invading the human perception. So through digital formats the image can develop an independent story. From one side the picture loosens its link with the referent and from the other seems to suggest not only an autonomous life of the image [

30] but also a disquieting world in which the human being withdraws according to a scenario that was probably perceived as too apocalyptic and catastrophic when it was conceived by Michel Foucault [

31]. Although it would be difficult to predict or confirm epochal changes only by some fascinating clues it is possible to argue that the forecasted last “

episteme” seems not to have defined boundaries yet. It is more probably a soft prelude to a post-human dimension in which humankind is still present but not so pivotal when images start reproducing in a viral way.

5. Anthropological Imagery

The instantaneous transition from an image to another with a simple mouse click suggests an equivalence of all the different images on the display. Nowadays it is possible to travel all around the world in real time just watching a screen so that every place on earth can be visualized in real time (

Figure 9).

According to Manuel Castells [

32] the network society is both local and global and benefits from expansive and instantaneous elements of internationalization based on seamless multimedia connectivity. The parallel effect on the web people seems to be a constant shaping and reshaping of aesthetic criteria, a fall down of the Aristotelian principle of non-contradiction. The connected man has plural identities based on impermanence, lives in a sort of nomadism of conscience as a “

web-flaneur” gives hierarchies up, does not care about contexts etc. Nowadays, in fact, many Flickr, Instagram or Pinterest pages (“

The world’s catalog of ideas” as the website says) collect the most varied typologies of images, sometimes with no, or very weak, specific connections. To interpret this mental attitude a suggesting parallel from anthropology can be quoted to focus better the backdrop of the weakening of writing in front of the visual.

When Jack Goody [

33] tried to focus the consequences of literacy he could argue that the lack of a tradition of alphabetic writing bears a “

structural amnesia” which blurs the distinction between the past and the present. Probably it is just the primacy of the visual that allows web users to override places, memories and contradictions. Many other interpretations for an anthropology of the interconnected man can be borrowed from a glance to the past great time leaps with deep effects on sensibility and mental shape. If web users or virtual communities can be regarded by Castells as a particular form of digital citizenship then the passage from traditional media, limited in quantity and fruition, to digital media, virtually boundless and instantaneous, can be put easily in comparison with the urban explosion occurred during the nineteenth century.

Georg Simmel in

The Metropolis and Mental Life [

34] argued that in a great city people are under flows of images, incitements, impressions that fight for a place in human mind. The rhythm of life and of sensorial images in a great city are always in evolution and, to survive the overstimulation, citizen must develop a more sophisticated, detached and basically not involved attitude. It is difficult not to think that the multimedia hubbub of the web can have the same effect on internet surfers. Of course there is also a great advantage in matching real and virtual space especially for professionals, designers and creative people.

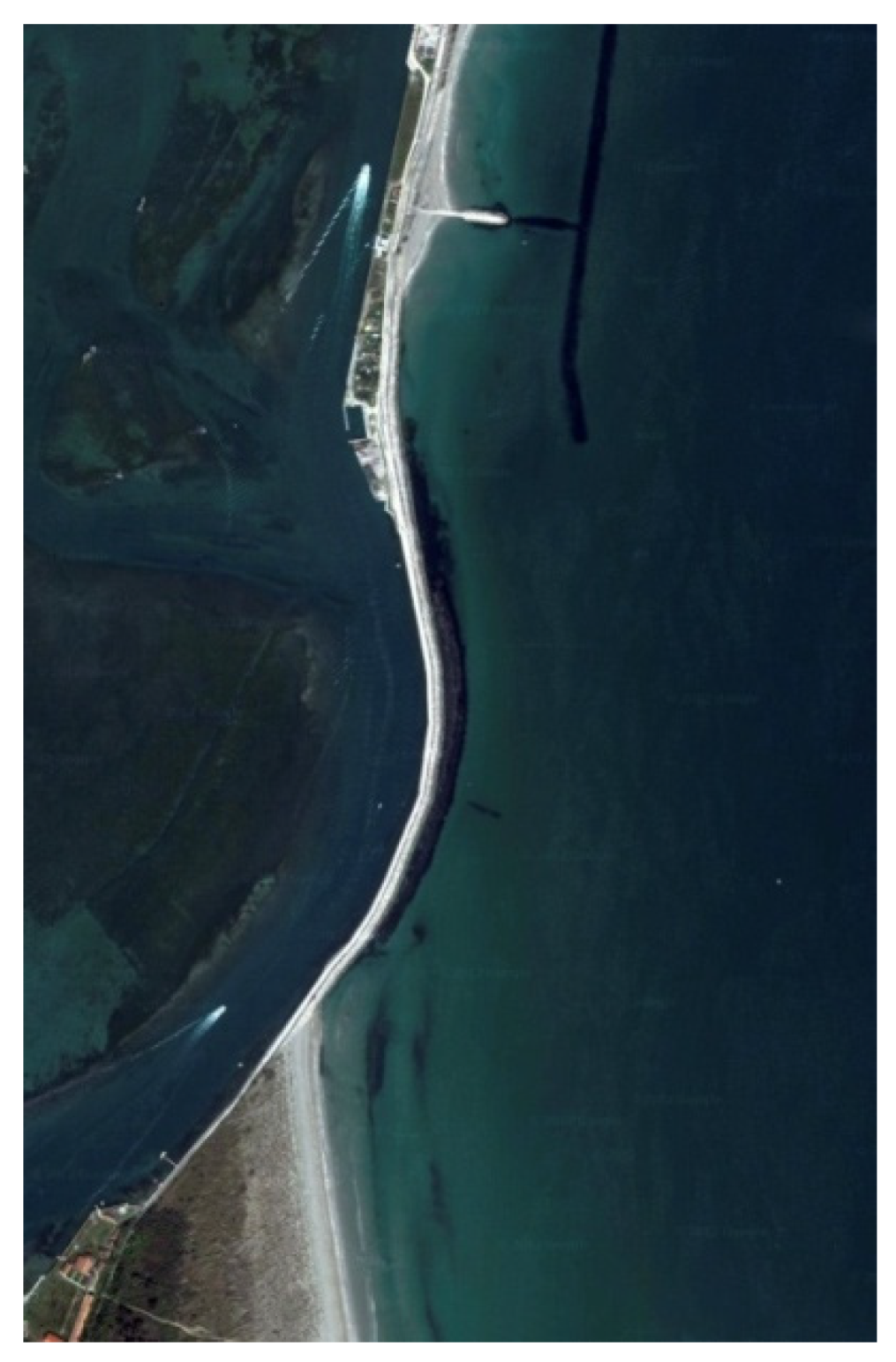

Many authors have started to consider the web wandering as a powerful source of inspiration and research. Marco Introini, probably the most important Italian contemporary landscape and architecture photographer, uses the web exploration of the territory to find a proper location for his shooting set (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). After a preliminary overview on Google earth looking for cliffs, shores, landscapes etc. the field trip can be planned more carefully and unexpected opportunities can be discovered.

This is definitely significant just for the inevitable mutual references that is possible to find on the ground of the representation trough the web. The new the role of web-imagination to approach the world and to build it through icons over the real recalls in some ways the forecast of the “

precession of simulacra” by Baudrillard [

35].

It is possible, in other words, to walk across the world moving from a landscape to another and from the present to the past or the future although the hidden risk is an image consumption based on uncritical indifference and a dégagé cosmopolitanism.

The role of media consumption, after all, has been already focused as one of the main features of a long time trend that marked the advent of the affluent society [

36,

37]. More specifically Zygmunt Bauman found a parallel of his concept of liquid society in what he called

Liquid Arts [

38]. Bauman noticed how consumerism needs and seeks continuous novelties always on the edge of waste and exhaustion.

But how to contrast the commodification of icons and the loss of sensibility towards the image? The solution can be found on the web itself and on the communication network provided by the digital.

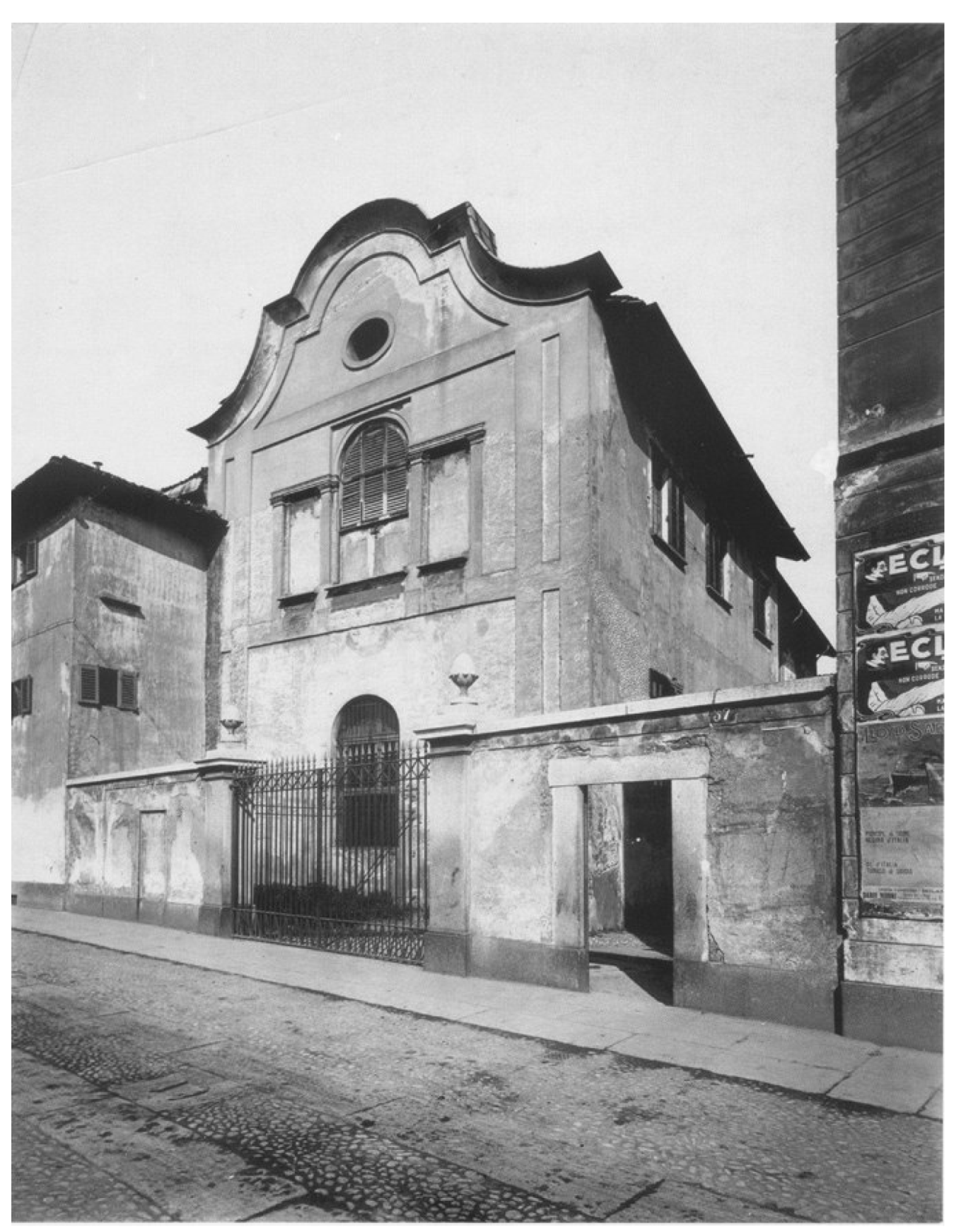

The most interesting examples of communicative environment on this point are web communities and forums. In many platforms for public discussion about the city the image of the space have a central role, or better, the image is the origin and the underlying cause of success for an open forum. It should not need to be pointed out once again how our visual perception has been influenced by electronic communications since the late nineties especially in reference to the city [

39]. Discussion forums such as “skyscrapercity” [

40], a group of sites for public debate with a global diffusion in all the continents, record the greatest success for topics most provided with photos, drawings, digital reproductions. The case of Milan, from this point of view, is a significant example. The forum about recent urban transformations [

41] can collect passionate supporters side by side with another one devoted to the disappeared city [

42] (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

The constant request for information about forgotten destroyed monuments, erased places, spatial references, constructive processes or final performance of a building under construction can re-establish a connection between place and representation just trough the communities of learning which look together for a shared vision. In this way the image can be, on the contrary, a very place-based tool to shape an identity, a local pride, a common culture for the future. In this way the web is not only an opencast mine for images but also a place for a citizenship, an ethnic group or even a subculture to envision or revisit neglected sides of a local tradition. The digital world therefore can be also the best place to communicate unusual images or unexpected beauties of a city.

6. The Digital Trace

There is anyway a hidden advantage in embedding contents in the web. It is unlikely that an image entrusted to the Net will be lost forever. The countless opportunities to reproduce at nearly no cost an image make it resistant to the destruction owing to the elapsing of time. The question is: could it be possible for an unknown or misanthropic author (e.g., Vivian Mayer) to remain unknown or for her photos collection to be sent for pulping? Probably it would not be so easy in the age of the digital reproduction. This aspect of the digital presence of images drives to consider the question from a grammatological point of view. Derrida [

43] from his approach to Husserl’s phenomenology stressed the concept of “

trace” as a mark of the human presence in history beyond death. The trace, the writing or in our case the image, can surpass the sound, or the simple vision, because it can persist in time and it will be open to interpretation in the future. Although Derrida could not forecast the dramatic range of today’s digital communication, in some way, he could catch the dawn of a phenomenon and recently the question of images has started to be related specifically to the field of grammatology [

44] Moreover the suggestion of the well known metaphor of Derrida’s thought is just the postcard [

45] which, as well as philosophy, takes its reason from being shipped and always on the track. In the age of the digital the image is just a Derrida’s postcard as it shows its nature by being continuously uploaded, sent, edited and duplicated. (

Figure 14).

An evidence of this new dimension of the digital persistence of the images can be found in many urban and performing artists such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Spencer Tunick, Léo Caillard, Geoffroy Mottart etc. After the digital turn they can find the optimal development for their works just through photos, images or short clips that can live as pure visions on the web after the end of the happening (

Figure 15). This is true also for group performances: the Sydney dance company posing naked [

46] for the Tate Collection exhibition as well as the collective world group dancers “I Charleston” [

47] who make videos of themselves doing Charleston in front of famous places and post them on the Net. The most amazing success in recent times has been achieved by the famous street artist Banksy who, in spite of his place-based work, is now a viral phenomenon of the web.

In this regard even more significant is the fact that one of his work (a stencil in Jamaica) was accidentally erased during the maintenance work in a hotel [

48]. The list of similar examples would be long but probably the best conclusion must be left to a young Philippine girl, hitherto unknown, who, after a diagnosis of terminal cancer, took a touching and upsetting decision. In front of death Racine Pregunta [

49] wanted to be photographed with her best dress and the best make up during her funeral. It goes without saying that her photos were posted by her sister on a social media and that was her final chance to be beautiful forever.